6

ALASKA PANHANDLE

Prince Rupert to Juneau 382/1,150 miles

Prince Rupert to Juneau 382/1,150 miles

The frontiers are not East or West,

North or South,

but wherever a man fronts a fact.

—HENRY DAVID THOREAU

The last frontier. Alaska hangs off the shoulder of the North American continent like the proverbial carrot and stick, and attracts a diverse assortment of characters with peculiar predilections. Dreamers, cranks, end-of-the-roaders, all manner of people make their way north or, having had the blessing of Alaskan birth, remain. Many are back-to-the-landers: wannabe trappers, homesteaders, or pot farmers; some are angst-ridden greens. A few are fed-up militia misfits, Libertarian idealists, or just run-of-the-mill misanthropes; most are insufferably self-reliant—and competent—egoists. Soldiers, petty bureaucrats, and resource extractors, drawn by big bucks to endure two-year stints in the bush, commit, endure, and often burn out. All have found a welcome niche in Alaska. That is, for as long as they can abide the dark, the damp, and the cold. Not a few are socially inept, given to non sequiturs and conversational spurts and lapses reminiscent of communication on time-delayed satellite radios, complete with bad reception. Most are vulnerable sorts, often overly friendly, open, and honest, yet suspicious and quick to anger. All are eccentric to a fault. It is truly a quaff of fine ale. To a special sort of woman, these are MEN, real men.

Chuck La Queue (his real alias) is a real man. Tall, hirsute—handsome, in spite of his thick Barry Goldwater glasses—and slightly lordotic, Chuck drove his VW microbus to Alaska to prospect a job with the newly approved Trans-Alaska Pipeline project in 1973. Accosted at the border by overly enthusiastic INS agents, he fought back with a full, double-barreled arsenal of a cappella Irish rebel songs at high volume and in a full-throated, resonant baritone. Chuck is a world-class kayaker. He was fresh off a first descent of the headwaters of the Amazon and needed a change. Unable to sign on with the Alyeska consortium immediately, he joined the commercial crab fishing fleet for a stint in the frigid waters of the Gulf of Alaska. He survived one season. Chuck wasn’t—and isn’t—a team player. Once, when planning a kayak expedition and short on funds, he tried a new approach to victualing. He’d heard that strapped inner-city senior citizens in New York City were resorting to subsisting on pet food for its value-to-volume efficiency, so he packed a month’s supply of Gaines-Burgers. When they turned out to taste like lard-laced sawdust with just a hint of offal, he tried cooking them. Though they were still inedible, he nonetheless ate them. To his grumbling teammate, a redhead with a limp whom he’d enlisted during a night of excess at the Red Dog Saloon in Fairbanks, he declared, like a disgruntled prospector (a profession he pursues intermittently), that if she didn’t like the way things had turned out, he’d “buy her out!”

Chuck is particular. Once, passing the time at a local watering hole, he befriended an attractive off-duty Tongass National Forest rangerette from the Ketchikan District. Passing time soon became making time. Since he’d been considering an Inside Passage paddle, he asked her in what direction the predominant winds blew. She responded that she hadn’t noticed. All of a sudden, Chuck visibly lost interest and left. Puzzled—they’d already locked eyeballs and were sniffing each other like dogs—I asked why he walked away from a sure prospect. “She’s unobservant,” he tersely declared with not a little contempt for her, her competence, the Forest Service, the question, and even me—for prying. Today, Chuck splits his time between working winters for the pipeline in Prudhoe Bay and doing construction in summertime Phoenix, Arizona. To do otherwise, he quietly avers, would be un-Alaskan.

Markle, another real man, is Chuck’s neighbor. In Detroit, before he moved to Alaska, he sold used cars. He lives in a mini-Quonset hut, uninsulated except for the stacks of books, clothes, and outdoor gear along the outside walls. An oversize wood-burning stove dominates the Quonset. Unlike Chuck, Markle has running water, phone, and electricity from a utility. Now he lives his passions: kayaking and mountaineering, at both of which he’s notably accomplished. When the outdoor season dawns, an intricate—and predictable—minuet ensues. Markle requests a sabbatical from his job. Invariably, he’s turned down. So he quits and goes off chasing what’s important to him. Upon his return, his old boss invariably rehires him. Seems his skills are indispensable. To supplement his income he sequesters himself with a phone for extended commodities-futures trading sessions. Markle, like Chuck, is unmarried and lives alone. Alaska has a disproportionate number of real men, or, as they say up there, “The odds are good, but the goods are odd.” And they attract a particular sort of woman.

We met Kristin on the water. She was kayaking to Alaska to find a real man. At 24, she was becomingly steatopygous with a strong upper torso to match. Barefoot, unkempt, and underdressed, with a shotgun slung from her shoulder, few men could resist her. Her eyes were pools of mystery; she was quiet and verbally shy. Pouty, everted lips shielded oversized and bunny-toothed incisors that hinted of prognathy. She had a perfectly rounded, dolichocephalic skull with a high forehead. A hint of lanugo caressed her cheeks. She was quite compelling in an untraditional sense. An assayer by trade, Kristin hailed from Dawson, Yukon Territory, and was traveling light—no stove, a simple tarp, no brand-name gear. She was obsessively focused on her quest, and no single man got away from her. She was literally testing every available male on her route, fishermen first. When we last heard of her—she was a minor legend by then—she’d taken up with a part-time fisherman and log salvager living at the edge of a small waterfront community.

Log salvaging, or beach logging, like gathering aluminum cans along rights-of-way in the Lower 48, is a handy source of pocket money and a not uncommon sight along the Inside Passage. The log salvager, one man working with a small skiff or inboard, often with his son, will scour sounds, inlets, passages, and beaches for escaped logs on the lam. On a bad day, suitable driftwood will suffice. Spotting a likely mark, the salvager will typically nose the boat up to the beach, jump out with a choke cable while the boat idles, hawse it around the log, jump back in, and hope his engine and skill can refloat it for a bounty. A sawmill will pay, depending on the species, upwards of $500 for a 50-foot-long, 18-inch-diameter log. The same size log, prime construction-grade Douglas fir, dressed—with little or no taper—might retail for $1,500.

The welcome sign in the park next to the chamber of commerce in Port Hardy encapsulates a particular view of the Northwest Coast: PORT HARDY: LOGGING, FISHING & MINING. The sign is incomplete; “Tourism” is missing. These pursuits are as intricately intertwined with the Northwest Coast as Guinness, sheep, and music are with Ireland. All four are pursued at industrial proportions; as family enterprises; and as individual efforts that supplement fluctuating and seasonal incomes.

Perhaps Alaska attracts its fair share of eccentric opportunists because, perceiving itself a tough sell, it has resorted to offering particularly attractive packages—thong-clad, some might say—of its resources. Allotted on an individual basis, some of these packages are outright giveaways. The 1862 Homestead Act, repealed in 1976, was resuscitated in Alaska in 1984 for an encore. Before the state act was terminated in 1991, 1,600 Alaskans were awarded homestead permits. It was still a tough sell. Only 12 percent proved up their land. In step with the generous land allotments, logging, fishing, mining, and tourism followed suit. During the early years, individuals could appropriate up to 25,000 board feet of lumber and 25 cords of wood from the Tongass National Forest. Trap fishing, outlawed virtually everywhere along the Inside Passage at a very early date, was outlawed in Alaska only at the time of statehood, in 1959. The controversial—and still extant—Mining Act of 1872 allows mineral claims on public land without payment of royalties and with allowances for patenting. The most innovative mineral giveaway has to be the Alaska Permanent Fund, established in 1976. Funded by oil revenues, the fund pays a dividend to every resident who has lived in Alaska for at least six months. The 2017 check totaled $1,110. For a time, the US Forest Service (USFS) allowed special use permits for recreational cabins in the Tongass. Today, the Forest Service maintains recreational cabins for public use at a nominal fee.

Logging

Along the Inside Passage, the trees are tightly spaced, the branches almost touch, and undergrowth clogs the understory, but the timber industry is as ever present as rain. Clear-cuts, abandoned roads to nowhere, booming grounds, tug-towed booms, pulp mills, solitary log salvagers, deadheads, helicopter skidders, log freighters, and lumber barges are each a visible component of an intricate and complex operation that we tried to accurately fit and sequence—like a puzzle—and then comprehend to keep our minds entertained while paddling. From the water, the forest seems impenetrable.

One day, in Sunderland Channel, the lateness of the hour and absence of beaches forced us to broach the forest battlements, enter and—improbably but desperately—look for a clear, flat spot. We were stunned. Inside, the forest opened up somewhat and little undergrowth grew. But the slash piles, oil spills, and garbage—the stink and detritus of loggers long (and not so long) past, dominated the scene and shocked us. Trained as an archaeologist, I must have been the only one of our group that found anything redeeming in the tableau. I looked for some diagnostic sign that might date the depredation. It was right there in front of us, invisible—a case of being unable to see the trees for the forest: giant stumps like spectral headstones commemorating a vanished world, 5 to 8 feet high and 6 to 8 feet in diameter; pockmarked with two to four incongruous ax-hewn niches always 2 or 3 feet below the flat top; and widely spaced among the spindly second- and third-growth saplings that had regenerated a mere 3 to 10 feet apart. So widely spaced were the big fellows that the scale of that extinct and unimaginable prehistoric forest must have been Brobdingnagian. We wanted to see—what in our mind’s eye we pictured as a Tolkien-like copse—such a forest.

A surprising number of locales along the Inside Passage, even in Puget Sound, are touted as being “old-growth,” or, as is now more common, first-growth. In a nutshell, old-growth forest is one that has never been logged. So we made a point of seeking out vestigial old-growth sanctuaries such as the Brothers Islands, just south of Admiralty Island. We were underwhelmed. True, there was gardenlike undergrowth—gorgeous moss and ferns—no stumps, and no sign of man. These islands had never been logged. But the trees were a humdrum 1 to 2 feet in diameter. We’d been expecting to see the old giants. We felt cheated.

The definition of old-growth can be a bit slippery. Up to 15 to 20 percent of a stand can be logged and still be considered old-growth; an entire forest can be clear-cut and also be considered old-growth if the event occurred more than 125 years ago. And tree size is not a factor. Local microclimatic conditions determine whether a particular stand of trees achieves its full genetic potential or not. And potential they do have. The largest trees were the Douglas fir, the Sitka spruce, and the western red cedar. Botanists theorize that the tendency toward gigantism is a function of millennia of genetic evolution uninterrupted by the glacial episodes of past ice ages. The Inside Passage was generally ice-free when much of the rest of North America was covered with ice. Certain arboreal genetic lineages advanced and retreated in step with the glacial advances along the ice-free corridor, adapting and surviving. What to our imagination are true old-growth forests—with trees averaging 8 feet in diameter, exceeding 200 feet in height, and more than 300 years old—are now rare and remote. Most have been logged.

At first, the Northwest Coast forests were perceived as an obstacle to be cleared. But the exceptional size and straightness of the timber won shipbuilders’ praise and proved better than Baltic stands for masts and spars. With the passing of the Age of Sail and increased settlement, lumber demand for terrestrial uses exploded. The first sawmills along the Inside Passage were built at Olympia and Victoria in 1848. Their lumber built San Francisco, Seattle, and Victoria. Alaska’s first sawmills were built by the Russians in Sitka and by the Americans in 1879 near Wrangell. During WWI and II, demand for Sitka spruce to build fighter planes and British Mosquito bombers soared.

All logs now end up at mills. Giant pulp mills—in Tacoma, Port Townsend, Nanaimo, Powell River, and Ketchikan (along our route)—predominate. Pulp mills are not picky; they’ll accept any tree, turn it into pulp, and make paper; 13 tons of wood yield 1 ton of paper. Some mills specialize in dissolving pulp—mostly from hemlock—which is further processed into rayon, cellophane, and plastics. Pulp mills even process wood chips and sawdust, sawmill by-products once burned as scrap but now in demand. Tugboats towing giant wood-chip barges from sawmills to pulp mills are a common sight along the Inside Passage. Although sawmills—many mom-and-pop operations—still eke out a decent livelihood, they play a lesser role. Exceptionally prime timber makes its way into lumber, particularly for Asian markets and for specialty uses such as plywood. On the one hand, dwindling timber resources and increasing populations have driven up demand and timber prices; on the other hand, engineered wood products (wafer board, glulam beams, particle board, etc.), steel, and concrete have replaced dearer lumber. While pulp mills are certainly an efficient way to use sawmill waste, demand for paper has also mushroomed, particularly since the advent of the computer and the “paperless office,” and no simple substitute has jumped into the breach.

Along the Inside Passage, logging mostly starts out as a one-to-one, mano-a-mano affair, one man vs. one tree. Lumberjacks, kited up like medieval knights—helmets, face guards, earmuffs, gloves, ballistic cloth chaps, steel-toed boots, and whirring lance of a chain saw with bars up to 4 feet in length—don’t cry “timber!” Individual sounds can’t penetrate the armor, just the aggregate hum of chain saws and skidders. One man can size up, notch, fell, and trim a 100-foot tall, 18-inch-diameter (without the bark) tree in well under half an hour. It wasn’t always so.

During the nineteenth century, Douglas firs along the Northwest Coast could reach 300 feet in height and 15 feet in diameter. No saw could span such girth; no one man could fell such a leviathan. To complicate matters, a tree’s foundation—its root system—funnels up into the trunk, forming an acutely tapering pediment that buttresses the tree and impedes its downfall. The stumps in this area, sometimes reaching 6 to 10 feet above the ground, become cull when the trees are rendered into lumber because the loggers always severed the trees well above their roots, where the tapers became more uniform. To reach this height, a temporary scaffold consisting of a single plank—called a springboard, like a diving board to nowhere—was wedged, without additional fasteners, into an ax-cut notch about 3 feet below the proposed cut line. The weight of the logger—and not a little faith—kept the plank from slipping out. Two planks, a saw-length’s separation on one side of a tree, provided minimal platforms for two well-balanced saw cutters.

First, the directional notch on the downhill side of the tree was cut about one-quarter to one-third through the tree. Then the loggers would switch to the opposite, uphill side of the tree and begin the felling cut, always noticeably above the directional notch. The sawyers would seesaw all the way to the saw’s capacity, usually no greater than 10 feet. The tree’s heartwood was then tackled with broadaxes measuring 16 inches at the face, until the tree’s weight gave way along the remaining thin hinge. At this point, nimble choppers executed a well-timed leap off the plank. Cutting one tree could consume an entire day. Then and now, a particularly prime tree’s landing would be cushioned by a bed of smaller trees and branches, to prevent splintering and kickback.

old-growth stump—note springboard notch on right

In the early days, steep topography was an asset. All trees would be felled downhill. If they needed help getting to the water after the branches had been trimmed, a series of smaller logs placed perpendicularly sometimes notched to keep the aim true and often greased—sometimes with whale oil (“greasing the skids”)—would aid the skidding process, getting the log to a common transport depot. At first, gravity was often sufficient to get a tree to the water; if not, trees were harnessed to horse and ox teams. “Donkey engines,” stationary steam or diesel motors with giant drums and cables, soon replaced the livestock. Today, giant bulldozers skid the timber.

Or, sometimes, helicopters. Expensive though it might seem, as both the distance from prime timber to the sea and the cost of extending access roads in increasingly rugged terrain have increased, heli-logging has come into its own. Without extensive logging roads, impact and erosion are minimized or eliminated. In some areas, under some resource management regimens, helicopters are the only viable skidders. But beware if you find yourself under their flight path. Newly guillotined and choked by a single cable, heli-logs rain down a constant shower of bark, branches, and detritus. In many cases, these prime logs are deposited directly onto a log-carrying barge for transport to a sawmill.

Self-loading log barges, 200 to 400 feet in length with crews of two to four, and log freighters—bigger still—are often seen in the distance, cruising outside waters. Empty, they resemble castle moat bridge supports with buttressing towers and cranes at the fore and aft ends. At a distance, empty or full, these squat castles unexpectedly puzzle. The logs are stacked crosswise on the decks and are unloaded by flooding water compartments on one side of the ship. The resulting list, or tilt, slides the logs off. Log ships transport unmilled logs over long distances or rough water, often to Asian markets. US regulations require Alaskan timber to undergo “primary processing” prior to export, usually into squared-off logs called cants. (Native-owned timber, according to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, is exempt; most of the high-quality native timber is shipped as raw logs to Japan.)

Logs are stockpiled at “booming” areas, the nearest protected waters adjacent to the cutting site or, at the receiving end, the lumber or pulp mill. Booming areas are defined by and subdivided into holding pens by perimeter logs strung together with cable and marked into lots for easy identification. At the Powell River pulp mill, exposed to the full fetch of the Strait of Georgia, the anchored, rusting hulls of surplus WWII merchant marine ships create the booming ground.

Transit between booming grounds is a tedious, labor-intensive, low-tech affair with long reaction times and minor episodes of tragic farce not unlike herding sheep, complete with maverick escapees. Transport holding pens, as above, sometimes and seemingly absurdly strung together in lengths as long as three, are hitched to a single tug for tow. Tugboats are not the most nimble wranglers. Basically gargantuan, seaworthy diesel engines, they are long on raw power but short on balletic grace. The log bundles are not hydrodynamic, immeasurably resist organization, and retain oodles of inertia. Kayaks often outpace tugged log bundles. Avoid them like drunken mendicants. Their reaction times are measured in increments of an hour, and current, wind, and sea conditions can discombobulate the entire jury-rigged affair. Getting started and docking a load are tests of patience and seamanship. For longer voyages and before the introduction of self-loading log barges and ships, the log bundles—with a great deal of pressure—were chained together into a cigar-shaped, single towable mass called a Davis raft, measuring 280 feet long by 60 feet wide and 30 feet deep.

Various entities own—and manage quite differently—different portions of the Inside Passage forests. In the state of Washington, besides national forests, parks, and various other federal, state, and local entities, a great deal of forested land is privately owned. Tacoma-based Weyerhaeuser owns much of its resource thanks to government subsidies, in the form of undeveloped acreage, granted the railroads after the Civil War as a quid pro quo for building line extensions. In 1900 Frederick Weyerhaeuser bought 900,000 of these acres from the Northern Pacific Railroad. Weyerhaeuser, Georgia-Pacific, and others now primarily manage “tree farms” on their deeded land.

British Columbia’s government owns 95 percent of the province’s forests and manages them through the BC Forest Service. Far from affording a venue for conservation, government ownership sometimes seems a detriment. Canada has always been imbued with an interventionist economic philosophy, in the belief that nothing gets done unless government lends a helping hand. Consequently, government takes an active part in growth and development by subsidizing resource exploitation. Leases to timber corporations such as MacMillan-Bloedel, BC Forest Products, Crown Pacific, and Western Forest Products, at exceptionally good terms, are the norm. “Dumping!” cry the Americans, and in May of 2002 the United States imposed duties averaging 27 percent on Canadian imports. “It’s the biggest trade battle on the planet,” said Pierre Pettigrew, Canada’s then trade minister.

On the other hand, government has lately been intervening more and more for conservation, setting aside more land for parks and removing acreage from consideration for timber leases. In 1997, under the Forest Practices Code, the Inside Passage (in the stricter sense, not the entire north coast) was declared a scenic area, a designation that means scenic integrity and not timber production will be the paramount planning guideline. According to the BC Forest Service, now only 16 percent of the north coast forest is considered available and suitable for logging.

The Tongass National Forest—the largest national forest in the United States—started life in 1902 as the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve. In 1907, Teddy Roosevelt substantially increased the reserve to create today’s Tongass National Forest, which encompasses 80 percent of all the land in Alaska’s southeast. Back then, “reserve” and “national” didn’t quite mean what they mean today.

As a timber resource, the great forests of the Lower 48 were quickly disappearing. So it seemed logical that the vast forests of newly acquired Alaska would continue to supply demand. At one time, laissez-faire market forces would have been allowed to operate unhindered. But in 1873, Karl Marx, in the first volume of Das Kapital, argued that a brain was needed behind Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” to control and guide it so it would make better choices: government. With policies developed centrally at the national level by disinterested experts, instead of the anarchy of self-interest of countless citizens, exploitation and extraction of the new resource could be maximized with greater efficiency. “Reserve” meant “reserved for exploitation” and “national” meant “officially nationalized for exploitation.” The US Forest Service was the entity of experts created to manage and promote economic exploitation of forest resources. From the beginning, they tried to bring economic development to Southeast Alaska by offering cheap timber to companies willing to build local mills.

But that now-handcuffed invisible hand was proving hard to direct. Even with subsidies, the distance, rugged terrain of Alaska, and cheapness of other timber sources attracted only local hand loggers and mom-and-pop sawmills to the Tongass. World War II and the postwar economic boom increased exploitation, but apparently not enough for the economic planners in Washington, D.C. In 1947, Congress passed the Tongass Timber Act, which not only authorized the Forest Service to offer generous incentives to timber companies, but also guaranteed that the subsidies would not deplete the agency’s annual funding. In one stroke of the economic planning pen, large-scale logging was now truly viable in Alaska.

Two takers stepped up to the trough: the soon-to-be Louisiana Pacific Paper Company and the Alaska Pulp Company (APC), a newly formed Japanese consortium incorporated in Juneau. The 50-year contracts that each were awarded built pulp mills in Ketchikan and Sitka, and brought growth and economic development to the panhandle. So as not to completely eliminate competition, the Forest Service reserved one-third of its “crop” for smaller operators. But free government money and a guaranteed majority stake are hard to resist, and corrupt completely. By the 1970s both Louisiana Pacific and APC had conspired to corner the market by buying out or forcing from business all competitors, then used the no-longer-competing competitors to manipulate federal timber auctions and thereby artificially depress the pulp market price. With an intricate but fraudulent shell game, both companies reshuffled vast profits to parent corporations to make the mills appear barely profitable and thereby secure lower timber prices. Since lower prices encourage consumption, panhandle forests suffered.

To make matters worse, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act awarded half a million acres of prime forest in Southeast Alaska to local native corporations. They soon set out to substantiate the fears that were the original impetus for the establishment of the failed reservation system: they logged with a vengeance in an attempt to make their corporations profitable. Within 10 years they had clear-cut as much as Louisiana Pacific and APC combined had razed since the 1950s.

But the tide was turning. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, people were beginning to value pristine forests not just as sources of timber and jobs but also for recreation, biodiversity, undevelopment, and just for their own sake. These nouveau values were exemplified by the Sierra Club, which now attracted legions of conservation-minded folk. The organization, founded in 1898 for hikers and climbers, had become a political powerhouse by 1960. Using a combination of lawsuits and lobbying, the Sierra Club was instrumental in beginning to reverse the status quo. In 1964, Congress passed the first Wilderness Act.

The conservationists’ unlikely ally was an independent logger whose 1981 lawsuit against the pulp mills exposed both the economic inequities in the Forest Service’s system and the fraud and corruption in Louisiana Pacific and APC. As more people learned that the Forest Service was losing millions of dollars on the Tongass timber program, taxpayers joined conservationists, hunters, fishermen, and small businesses in demanding reform. In 1984, Congress designated 5.4 million acres of Southeast Alaska as wilderness and turned the 2-million-acre Glacier Bay National Monument into a national park. But the real victory came in 1990 with the Tongass Timber Reform Act, which designated a further 1 million acres as wilderness, abolished the $40 million timber fund, and decreased the target cut. By 1997, Forest Service reforms, the burden of unresolved lawsuits, and accumulated pollution fines forced both companies to close their Alaskan pulp mill operations.

In 1999, a new Tongass Land Management Plan extended a broad panoply of protections to panhandle forests. Once spreading to more than 2,000 acres, today the average size of a Tongass clear-cut is 80 acres, and only 10 percent of the Tongass is scheduled for harvesting over the next 100 years.

Fishing

For a kayaker, fishing for fish that don’t eat is a true challenge. The most effective method for bagging a salmon along the Inside Passage is to beg, buy, flirt, or somehow talk your way into a salmon from a passing commercial fishing boat. Most will proudly offer a token of their catch. Gillnetters reeling in and clearing their nets are excellent prospects. Sometimes they snag out-of-season species that must be released. Most of the time the unfortunate fish is so damaged it can’t survive and, hating to waste an otherwise fine fish, the skipper is more than happy to see it somehow end up in a paddler’s larder. Keep a supply of plastic garbage bags handy in which to pack the salmon so as not to contaminate the kayak with fish smell. One hour or more before camping, stop at a handy beach to clean, fillet, cut up, and pack the meat in a small plastic bag. Discard the offal responsibly and burn the plastic garbage bag. Though it’s hard to beat barbecued salmon, you don’t want to attract uninvited ursine guests. Try boiling, er, poaching. Cleanup is a cinch, and the salmon is every bit as delicious. Season with salt, lemon, and pepper.

Commercial salmon fishing is strictly regulated according to political jurisdiction, season, fish stocks, salmon species (see Chapter 1 and Appendix D for habits and identifying features of each salmon variety), and methods of fishing. Three methods are commonly employed along Inside waters: trolling, gillnetting, and purse seining. Each type of boat is quite distinctive, but all are extremely common. They vary in length from 30 to 50 feet, with purse seiners sometimes reaching 100 feet.

the most effective way to catch a salmon from a kayak

Trolling is the simplest method. Two to four tall trolling poles, lowered to 45° for fishing, distinguish salmon trollers. Each pole deploys a weighted line with multiple lures. Although salmon don’t normally eat during the spawn, they retain a strong instinct to snap. The lines are hauled periodically, either by hand or with power winches—gurdies—and fish removed. Unlike netters, salmon trollers are not restricted to a certain area and range far and wide, with a crew of one or two for up to a week. An Alaskan hand-trolling license is relatively cheap and easy to acquire, allowing almost anyone to become a commercial fisherman. Elderly pioneers supplementing retirement income, well-off suburbanites writing off expensive cruisers as a business expense, aging hippies in rotting hulks, and men undergoing midlife crises all contribute to Alaska’s colorful cast of independent fishermen.

Gillnetters fish with a fine rectangular nylon net about 1,000 feet long by 20 wide. These are deployed in a straight line across a likely salmon travel path to snag the commuting fish by their gills. Floats—with a large, distinctive orange one supporting the end—hold the net up. Every one to four hours the nets are hauled up by a giant power drum—the gillnetter’s distinctive identifying feature (see photo on page 265)—and picked clean. Many are outfitted with trolling gear as well. Gillnetters often work in concert. Prior to the adoption of gasoline engines, oar and sail propelled trollers and gillnetters.

purse seiner

Purse seiners are more complicated, crewed by three to seven, and aided by a tubby skiff tender. Each fishing episode is a frenetic affair. When a school is located, the trap—a net about 1,200 feet long by 70 feet deep, supported by movable booms and shaped like an old-fashioned net purse (or scrotal sac) when closed—must be quickly set. The tender circles the prey widely with one end of the net and closes the circle, returning the net’s end to the seiner’s boom. The net is supported by floats and held vertically by weights at the bottom. If the set is successful, a line channeled through metal rings then draws the bottom of the purse tight. The purse is then hauled in and the catch sorted. No matter what the weather, seining crews work in complete foul-weather gear. Nets always capture jellyfish that inevitably end up cascading gelatinous stinging slime onto the crew. Purse seiners, easily identified by their nets aloft and pendant (or adjoining) tender, account for the largest proportion of commercially harvested wild salmon.

Some fishermen work independently, and others are on contract to commercial fish companies; all deliver their catch to fish-buying tenders and, in more remote areas, scows, whose crews often set their own lures: beer, liquor, cheap groceries, hot showers, whatever the market calls for. We ran into two competing fish-buying scows in Foggy Bay, halfway between Prince Rupert and Ketchikan. Though they may not retail fish, when not busy buying they might sell a kayaker some groceries or a shower.

Salmon are retailed fresh, smoked, frozen, or canned, depending on their quality. One outfit, kind enough to invite us in for a bed and a feed, specialized in smoked, spicy teriyaki king (Chinook) salmon. I couldn’t get enough of it. After dinner, a corporate floatplane landed at the dock and disembarked two formally suited and smiling Japanese, one with an attaché bag handcuffed to his wrist. “Our client,” whispered our generous host. Best smoked salmon I’ll ever taste.

In Alaska, the number of commercial fishing permits is limited. Someone wanting to enter the trade must buy an existing license from someone else. Prices reflect current demand. Back in the 1980s, power-trolling permits cost about $20,000. Catches are further limited by a complex schedule of openings and closings for different areas, different fishing methods, and different species, translating into long hours of intense work followed by extended periods of costly inactivity.

Since 1980, salmon farms have become a common sight along the BC coast. Salmon aquaculture was first developed in Norway and—when worldwide wild stocks began to shrink—spread to the UK, Chile, and Canada, where the helping hand of government provided generous subsidies. The fish are raised in net pens supported by rafts and are fed pellets just like in a home aquarium. When natural populations made a comeback in the 1990s, BC’s salmon farms experienced serious consolidation. Today (2018) there are only 80, but they supply a disproportionate majority of commercially marketed salmon. Canada is the fourth-largest producer of farmed salmon in the world. For the five years between 2011 and 2015, the annual average of farmed salmon produced in all of Canada was 122,300 tons with a value of $735.2 million. Though controversial, Atlantic salmon are the favorite fish species for farming due to their docility in tight quarters, larger size, and resistance to disease. As an artificially introduced species on the Pacific Coast, escaped Atlantic salmon pose the dangers of predation, competition, displacement, and increased risk of disease to the native populations. Consequently, Alaska bans finfish aquaculture and Washington very stringently regulates it. In 1999, sea lice were reported on wild salmon near Vancouver Island fish farms; Atlantic salmon are the suspected culprits. It is one more point of contention in the ongoing US-Canada fish wars.

The commercial salmon industry along the Inside Passage dates back to the 1820s, when the Hudson’s Bay Company shipped salted salmon to markets in Hawaii, China, Australia, England, and America’s Eastern Seaboard. The salmon, more often than not, arrived in less than prime condition. Although Nicolas Appert had invented the canning process in 1809 under the funding and direction of France’s war department, the technology spread slowly. For one thing, Napoleonic France was not known for sharing much of anything other than grief and subversion; additionally, the strange new process was suspect. It would be another 50 years before Louis Pasteur was able to explain why the process worked.

The first salmon cannery in British Columbia opened for business in 1870 near Vancouver. Canneries in Puget Sound—at Mukilteo in 1877—and Alaska—at Sitka and Klawock in 1878—soon followed. By 1901 there were 70 canneries along BC’s coast, and Alaska wasn’t far behind. Haines, Wrangell, and Petersburg all had canneries. At one time, during the 1920s, 25 canneries were operating on Prince of Wales Island alone. In 1940, Ketchikan had 13 canneries. Today, few active canneries survive, while the rest, haunted carapaces of an abandoned industry, are succumbing to fecund decay and encroaching salal, alder, and berry bushes.

By the end of WWII, overfishing was taking its toll and stocks began a gradual, determined, and ultimately precipitous decline. Fishermen and canneries went bust. Salmon prices soared. Governments and private interests poured money into research. Finally, in the 1970s, hatcheries succeeded in producing viable salmon that could be reintroduced successfully. By the 1990s, many stocks were well on their way to recovery. But the canneries never came back. By and large, modern refrigeration and freezing have superseded Appert’s invention. You can tour the Deer Mountain Hatchery in Ketchikan and the Douglas Island Pink and Chum Hatchery in Juneau.

Halibut fishing is second only to salmon in weight yield and importance. A bottom-feeder with both eyes on its “top side,” halibut can reach 500 pounds. Since it lives as deep as 3,600 feet, special single-hook fishing techniques are required to bag one. Its meat is white, flaky, and exceptionally delicious.

Oyster and, to a lesser degree, mussel farms are found all the way from Puget Sound to the Wrangell area. Because they need warmer water, most of the farms are south of Port Hardy. Alaskan oyster farming began near Ketchikan in 1930 from imported Japanese spat (baby oysters); today, Alaskan-reared Pacific oysters are grown from spat imported from the Lower 48. The farms are modest affairs, invariably marked if the critters are raised on the bottom, or recognizable as floating rafts.

Finally, probably the most ubiquitous—albeit humble—landmarks (seamarks?) along the entire paddle are shrimp and crab pots. You can spot these by their telltale floats, sometimes in the unlikeliest of places, which mark their location and anchor the trap. Shaped like big cheese wheels, the traps are crafted of wire mesh and baited. A funneled one-way opening secures the catch.

As of 2011, fishing was the number one private sector employer in Alaska, providing more jobs than oil, gas, timber, and tourism. The 2009 harvest of 1.84 million metric tons of fish and shellfish was worth $1.3 billion.

Mining

When Ginger and Dana Lamb set out to kayak from San Diego to Panama (see the Introduction) during the Great Depression, they supplemented their meager resources with a .22 caliber rifle for hunting and a gold pan for spending money. Today’s kayakers—some, at least—are not quite so penurious.

However, walking-around money is always a welcome addition to any excursion. You too, in the time-honored tradition of the Lambs and the hundreds of thousands of prospectors that made their way up the Inside Passage, can supplement your pocket money by placer mining for gold. All you need is a pan and a small, folding army surplus shovel—or the sturdy blade of a paddle.

Placer-mining is the oldest method of recovering gold from alluvial deposits. Gold, locked in strata high up in the mountains, is freed through erosion and wends its way down creeks and rivers. The more turbulent the water, the heavier the material it can carry. As the stream slows, the heaviest particles settle out first. Placer-mining takes advantage of this principle. Panning employs a pan or a batea (a pan or basin with radial corrugations) in which a few handfuls—or a shovelful or paddleful—of dirt and a large amount of water are placed. By swirling the contents of the pan—as if aggressively panhandling—the miner washes the siliceous material over the side, leaving the gold and heavy materials behind.

The first gold strike along the Inside Passage, in 1850, was at Gold Harbour, in the Queen Charlotte Islands. It was short-lived. Only the original discovery panned out. Six years later, Indians discovered gold along the Fraser River and set off a gold rush that brought nearly 30,000 prospectors in one summer to the present-day Vancouver area. Many were disillusioned forty-niners. Most remained disillusioned.

Wrangell was originally founded by the Russians as a tiny outpost of empire to strengthen their claim against Hudson’s Bay Company incursions. It was immediately—and diplomatically—leased to the Brits. Gold strikes up the Stikine River and in the Cassiar Mountains in 1861, and again in 1873, ballooned it into a tent city of 15,000. During the last half of the 1860s and through the 1870s, there were many more gold discoveries along the BC coast, but none compared to the 1880 strike in Juneau, Alaska. In October of that year, a Tlingit guide led Sitka prospectors Richard Harris and Joe Juneau to the mouth of soon-to-be-named Gold Creek. It was a fabulous strike, and Harris and Juneau staked their claims along with a 160-acre townsite for the expected rush. That first year yielded $2.5 million in today’s dollars.

Juneau’s mother lode, the gold-bearing strata that fed the placer deposits, were the mountains immediately backing the new town: Gold Creek’s entire watershed, plus several adjoining watersheds. When placer mining’s easy pickings ran out, prospectors tackled underground lode mining, a much more time-consuming and capital-intensive affair. The extra effort afforded the necessary time for the development of a substantial settlement. Ironically, the first big underground mine was not behind Juneau but in front of it, across Gastineau Channel, on Douglas Island. Big underground mines on Mount Roberts, behind Juneau, soon followed. The not-so-pure gold ore required purification. So, in 1889, the Tacoma Smelting and Refining Company set up shop in Puget Sound to refine gold at first, and later, as those deposits became depleted, silver, lead, and copper from the Juneau-Douglas mines. Mining in Juneau continued for 64 years, until it ceased in 1944. Paddling into Alaska’s capital, one of the first sights you’ll encounter is the ruin of the Alaska Juneau Mining Company, along with numberless adits, looming vertiginously over the city.

We made a beeline for Gold Creek to see where all the commotion had first started. What a grand disappointment! I suppose it was inevitable that the stream suffered during the gold rush, but the solution almost seems worse. One sorry little sign commemorates Juneau’s founding. The channel has been unelaborately and inartfully lined with concrete, without a thought for the poor salmon. We watched the pathetically heartbreaking attempts of a dozen superpiscine salmon fighting to make their way upstream. There wasn’t enough water in the wide channel for the fish to gain a fin- or tailhold. With Juneau’s receptivity to tourism, it’s a wonder no restoration has been attempted. Amazingly, one local paddler told us that the city had been offered a grant for just such a project but unexplainably turned it down.

The biggest gold rush of all along the Inside Passage burst upon the world in 1897 but did not take place anywhere near the Inside Passage’s protected waters. The previous year, when “Lying” George Carmack and his sidekicks, Skookum Jim and Tagish Charley, boasted of striking pay dirt at a small creek just east of Dawson City, Yukon, no one believed them. Until, that is, Carmack showed off a thumb-sized nugget of pure gold he’d picked off a protruding bit of bedrock. Local prospectors, working at Fortymile just west of Dawson, rushed to stake out the best claims. But it would take nearly a year and a 1,700-mile voyage down the Yukon River, plus the passage to San Francisco and Seattle, before news of the strike hit the press. The dispatch came in the form of suitcases, carpetbags, packing cases, bottles, cans, and every other type of container imaginable filled to bursting with 2 tons of pure gold unloaded at the San Francisco docks. The stampede was on.

Dawson City was not the most accessible destination. The simplest route was up the Pacific to Skagway or Dyea, then 20 miles up and across the Coast Range through Chilkoot or White Pass, and another 450 miles north down the Yukon River to Dawson. Regular steamship service, inaugurated during the Juneau rush, quickly reached capacity.

So more vessels provided passage. Over 100,000 treasure seekers set out for the Klondike; maybe 40,000 reached Dawson City. As more and more ships—some barely meriting the designation—plied their way north, those sailing in winter, and particularly those not fully up to the rigors of sailing Outside, rediscovered the protected waters Inside. Thus was the truly greatest bonanza of all unearthed—Inside Passage tourism.

Though seemingly much more mundane than gold, the discovery of coal along the Inside Passage in some ways had a greater and more lasting impact. Welsh coal, at tremendous expense, fed all the metallurgical industries in the nascent colony. In 1849, one year before the first gold strike in the Queen Charlottes, a Heiltsuk native at Bella Bella’s Fort McLoughlin observed a blacksmith impose his will on a piece of iron with the help of black rocks. When the native found out that the coal came from halfway around the world, he told the smith that there were black rocks a lot closer, near his home by present-day Port Hardy. The Hudson’s Bay Company confirmed the find, established Fort Rupert to protect the site, and imported English miners, as they doubted that the natives would make good coal miners. Both the Beaver and the newer trading vessel, the Otter, were immediately converted from wood to coal—one small step in the conservation of the BC forests.

Three years later, a much higher-quality coal was discovered at Nanaimo, so the HBC built a fortification, the Bastion (still there), and transferred the miners down from Fort Rupert. The Nanaimo seam proved extensive and very productive well into the twentieth century. Nanaimo coal was exported to Puget Sound and San Francisco. Kayakers can visit some of the preserved adits—one tunnel is reputed to lead all the way across Newcastle Island Passage to Nanaimo—on Newcastle Island, named after the miners’ hometown in England. Coal was also later discovered at Bellingham in Puget Sound.

For such a small place, Newcastle Island was a cornucopia of mineral goodies. The search for flawless quarry stone for the newly proposed San Francisco mint ended in 1869 with the discovery of perfect sandstone on Newcastle. The quarry supplied large monolithic blocks for much of the Northwest’s grandiose public architecture—including the towers of Christ Church Cathedral in Victoria—until 1932, by which time the coal mining and stone quarrying had totally trashed the island. In 1931, the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company bought what was left of the little island and developed it into a park resort. The sandstone quarry exhibit on the park’s perimeter walk is very impressive.

The largest and most visible mining operation that a paddler will see along the Inside Passage is on the approach to Texada Island. We joked that from a distance it looked like the largest kitty litter quarry in the world. Since 1887, Texada has yielded huge amounts of high-quality limestone. Today it ships 3 million tons a year to the BC market for use in the pulp mills, agriculture, and the construction industry—for quicklime, cement, quarry rock, and even marble (due to part of the limestone strata adjoining an igneous lens), limestone’s metamorphic reincarnation.

The region’s most controversial open-pit mining operation—which an Inside Passage paddler is unlikely to encounter—is located deep in Misty Fjords National Monument. In 1974, the US Borax Corporation patented what was later identified as the largest molybdenum deposit in the world—perhaps 10 percent of known reserves—at Quartz Hill, about halfway between Behm Canal and the Canadian border. Molybdenum is used to harden and retard the corrosion of steel and other alloys. The claim remains valid since it predates the National Monument designation. As of this writing, market prices preclude any mining activity.

The Coast Range and its offshore islands have been heavily mineralized due to tectonic forces at the Pacific-North American Plate interface. In addition to gold, molybdenum, and coal, large deposits of silver, copper, lead, iron, zinc, uranium, asbestos, and jade have, in most cases, been mined and exhausted. Presently there is very little mining going on along the coast, with the notable exception of Texada Island and a potash mine on Ridley Island outside Prince Rupert.

Tourism

Tourist: One that travels from place to place

for pleasure or culture.

—WEBSTER’S THIRD NEW INTERNATIONAL DICTIONARY

Arguably, one of the earliest and most famous self-described tourists to visit the Inside Passage was John Muir. Muir steamed to Wrangell and canoed to Glacier Bay in 1879, when the Alaska purchase was only 12 years old. Many more were soon to follow, albeit not in quite his frugal style. Muir’s account of his visit proved so inspiring that steamship companies began to offer summer tours up the Inside Passage. The first was the steamer Idaho, which came north in 1883. The tourism industry was launched. By 1889, 5,000 tourists a year were making the trip up the Inside Passage. According to Tourism Vancouver, over 1 million cruise ships visit the Inside Passage annually. Mind you, that is cruise ship with a small “c”—anything from the gargantuan liners of the Royal Norwegian Line to, yes, solitary kayaks and every imaginable craft in between.

Cruise ships come in many categories. The big behemoths—many painted an imperious and dazzling white—dominate, if not in numbers, at least in sheer size. British Columbia and Alaska ferries qualify—and they can barely keep up with demand. Were it not for the sheer number of do-it-yourself, boatless summer visitors, ferry bookings would not require advance notice. A variety of smaller-scale cruises cater to the educational, ecotourism, and mother-ship kayak touring markets. An increasing number of kayak tour companies find a way to scratch out a living. A few offer land-and-water tour combos. Finally, in sheer numbers, private boats—from elaborate sailing rigs and luxurious yachts, to ambitious, modest-sized inboard and outboard vessels occasionally testing their limits, to trans-Inside Passage kayakers, rowers, and canoeists—fill out the flotilla.

In spite of the clarification, the numbers are still staggering. Nearly 1.25 million cruise ship (with a capital “C”) passengers toured the Inside Passage in 2017. Holland America and Princess Cruises alone made over 1,000 port calls—combined—in Alaska in 2017, with Juneau and Ketchikan together hosting nearly that many cruise ship stops during the 2017 summer. Little Ketchikan, with a population of only 7,000, is sometimes overwhelmed by between 10,000 to—some residents fear on current projections—20,000 visitors a day! Cruise ships carry about 2,000 passengers per ship with another 1,000 as crew. However, the ships are getting bigger: Royal Caribbean’s Ovation of the Seas, with a capacity of 5,000 (1,500 crew), is slated to visit Alaskan waters in 2019. While most of these self-contained floating cities measure about 700 feet in length and float 20 stories tall, the Ovation of the Seas stretches to 1,142 feet. When several vessels are in port simultaneously, they dwarf Alaska’s capital city’s buildings. The resident population of most towns along the Inside Passage doubles during the tourist season to accommodate the influx. Still, between May 1 and September 30, cruise ship passengers will spend an average of $1,233,000 every day in Juneau alone. Docking facilities in many towns, which once accommodated both ferries and cruise ships, have had to be rebuilt with separate berths. Plenty of Alaskans are grateful for the visits; others have mixed views of the cruise ship crowds.

With good reason. The sheer numbers are starting to sully the very beauty that brings visitors north in the first place. A typical cruise ship generates about 210,000 gallons of raw sewage a week, lesser amounts of oil, assorted hazardous wastes, and more than a million gallons of gray water. Not all ships are as fully self-contained as they ought to be. In 1998, Holland America pleaded guilty to two felony counts of illegal dumping in waters near Juneau. The next year, Royal Caribbean pleaded guilty to seven felony charges for dumping oily bilge water and toxic chemicals into Southeast Alaska’s waters. The company had rigged ships with secret piping systems to bypass oily water separators, and then falsified records to conceal the dumping. In 2000, 79 water samples from 80 cruise ships’ wastewater storage tanks—stuff normally expelled into the ocean—exceeded federal minimum standards for suspended solids and fecal coliform bacteria. Some samples exceeded the criteria by 50,000 times! But, to most Alaskans, the very worst, the truly ultimate tragedy, occurred when a cruise ship struck and killed a 45-foot pregnant humpback whale near the entrance to Glacier Bay National Park.

In 1996, the National Park Service, reacting to increased demand, made plans to increase the number of cruise ships allowed into Glacier Bay National Park by 30 percent, from 107 to 139 per season. Fearful that the consequences could be dire, the National Parks Conservation Association, a public interest group, filed suit on the grounds that no environmental impact study had been done. In 2001, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed. The NPS had to roll back cruise ship visits and complete an environmental impact study. The state of Alaska also stepped in.

In June 2001, Governor Tony Knowles convened a special session of the state legislature for the express purpose of addressing water pollution, air pollution, and trash disposal from cruise ships. The legislation passed and immediately went into effect. Now an even tougher measure, based on a 1999 $5 per-passenger tax levied by the city of Juneau, is being proposed through a statewide ballot initiative. As much as a $50 per-head tax would be imposed on tourists entering Alaska on cruise ships. The Northwest Cruise Ship Association believes such a tax would deter visitors. With cruise ship traffic increasing at a rate of about 10 percent per year, many voters don’t seem to think so.

When a cruise ship sails past, most kayakers are struck by the contrast between themselves and the passengers. Though both share the same purpose, the methods differ—vastly. Cruise ship tourists generally admire kayakers but think they’re a tad crazy. Kayakers’ attitudes toward cruisers range from dismissive to contemptuous. What’s it like to trade places?

A typical cruise lasts one week, makes six stops of 8 to 10 hours, and averages, at the moderate end, about $800. According to Peter Schmit, a passenger in 2002:

Our ship, built in late 1999, was home to 2000 passengers, with a crew of 950. It is literally a city at sea. It has its own sewage treatment and water desalination plants, eight restaurants, 12 bars and lounges, two swimming pools, a spa, a beautiful fitness center, running track around the perimeter (3.5 laps made a mile), a library, gambling casino, a 1000-seat theater, and way too many shops. The 80,000-ton ship cruised at about 22 miles per hour.

Most cruise ship tourists rave about their experience and would highly recommend it. Though it’s definitely not my idea of a good time, it’s no wonder the industry is growing so fast. Even my 70-year-old mother cruised to Alaska. More amazingly, some kayakers are even extending cruisers the hand of friendship. Lately, scuttlebutt has it that one Alaskan Inside Passage kayaker has taken to promoting his book with slide and lecture presentations on cruise ships.

Natural History

The Alaska Panhandle has always seemed an odd extension of Alaskan territorial integrity. More a historical accident than an integral part of the main Alaskan landmass, at one time it was Alaska. It was the rest of Alaska, the landmass west of 141° longitude and north of the panhandle—in effect, Seward’s Icebox—that, pretty much by default, was lumped together with the rich southeast. Southeast was hospitable. It was home to as many salmon as the mainland had mosquitoes, it nurtured forests that made the rest of Alaska look like it was on chemotherapy, and it was home to the sea otter, that little floating gold mine that brought the Russians over in the first place.

Although the Russians made inroads north of Southeast, there was little to attract or keep them there. And they never ventured east of the panhandle. Not only was the Coast Range impenetrable, but British westward expansion put paid to that notion. The brewing controversy was negotiated in 1825 under the auspices of the Convention of February, when the Russians and British settled on a serpentine border that addressed each power’s concerns. Russia wanted the entire littoral for fishing and whaling, and marine access to native communities for trading; Britain was little interested in the coastline, but wanted as much of the inland terrain as possible to maintain its fur trade. The new border had only been cursorily confirmed at the time of the Alaska Purchase. When gold was discovered in the Klondike and thousands invaded the panhandle, a serious border dispute arose. There was even talk of war.

When Britain rejected war out of hand and offered to arbitrate, Canadians took up the offer because they thought Britain was on their side. The United States also agreed because they had not rejected war as an option, and had in fact just won a war that added Hawaii, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, and had a new president, Theodore Roosevelt, that carried a “big stick” in foreign policy. Canada, wanting sea access for the Yukon, claimed the heads of the major inlets; the United States wanted the Russo-British line honored. Negotiations were further complicated by the fact that Canada, at this time, still lacked full treaty negotiating power. Britain, in 1903, sided with the United States; however, the boundary survey was not completed until 1914.

The Dixon Entrance, the second and smaller of the two main bodies of open water to be crossed on the Inside Passage, roughly marks the US-Canada boundary. North of it, a very dense maze of islands sets the panhandle apart from Canada. According to the US Forest Service, there are 2,000 islands along Alaska’s southeast coast. The Alexander Archipelago, as they are collectively known, is striking in its cohesiveness, extent, and the size of the major islands. Prince of Wales Island, at 2,770 square miles, is the largest. Paleontological excavations at El Capitan Cave on Prince of Wales Island reveal that there were black bears there 20,000 years ago and brown bears 40,000 years ago, indicating that there were ice-free locales along the Inside Passage during major glacial advances. Ironically, today along the panhandle, brown bears are limited to the mainland and the ABC Islands—Admiralty, Baranof, and Chichagof, with all three measuring just a tad smaller than bear-free Prince of Wales.

After central British Columbia, the panhandle section might seem overpopulated, with 70,000 residents in 33 communities. Fortunately, nearly all the people are concentrated in relatively large towns along our route—Prince Rupert, Metlakatla, Port Simpson, Saxman, Ketchikan, Myers Chuck, Wrangell, Petersburg, Junea, and Douglas. Campsites are not as scarce as in BC, but neither are they as plentiful as in the Gulf Islands.

Southeast Alaska is different—and not just in contrast to the main part of the state, as previously noted. Latitudinal changes, subtle in quality and degree—none quite so striking as the disappearance of the madrona north of Desolation Sound—have been accruing during our progress north. The “land of the midnight sun” effect is striking. On June 21—the longest day of the year—the sun rises about 4 AM and sets about 10 PM. Because the sun is circling just below the horizon, most of the few nighttime hours are in twilight. No need for a flashlight. At the other end of the year, midwinter Juneau has only about six hours of daylight, with sunrise at about 8:45 AM and sunset at about 3:00 PM.

dixon entrance lunch stop

Alaska weather is just a tad brusquer, egged on no doubt by the nearly 3,000 square miles of the Juneau and Stikine Ice Fields. Rain and fog are more frequent. Low-pressure fronts, which in summer break through the Pacific High about every two to six weeks along the lower Inside Passage, occur at intervals of one to three weeks in Southeast. Although these fronts usually last only a day or two, in Southeast they can stall out and linger longer. Accompanying winds are commensurately stronger. In lower BC, low-pressure fronts typically generate winds of 20 to 25 knots; in Southeast, the same fronts blow harder, around 30 knots, with occasional summertime gale-force blows. Watch out for these.

The Alexander Archipelago is very protected, particularly along our route, which courses as far east as possible. However, many of the channels and passages are quite wide and long. The accompanying fetch and exposure to the force of storm winds can create rough seas. Crossings of Portland and Behm Canals, Frederick Sound, and Stephens Passage are long enough for conditions to change during a crossing. Always be aware of diurnal and atmospheric wind changes.

With a handy wrist barometer, such as the Suunto, you can monitor atmospheric wind. Wind velocity is directly proportional to the rate of barometric pressure change—up or down. Falling pressure of 1 millibar per hour equals 20- to 30-knot winds; 2 millibars per hour equals 35- to 45-knot winds; while 3 millibars per hour translates to 50- to 60-knot storm winds. On the rising scale, 1 millibar per hour generates gale winds of 25 to 40 knots.

After cruising in BC and listening to Environment Canada’s marine weather forecasts, Alaskan forecasts might be slightly disappointing. Environment Canada prepares forecasts several times a day and broadcasts continuously on VHF weather channels. Lots of repeater stations provide adequate coverage all the way up to Ketchikan. In contrast, the National Weather Service in Juneau issues only one forecast a day, at 5 AM, and repeats it every five minutes on Weather Channel 1 or 2. Transmitters are located only in Haines, Juneau, Sitka, Wrangell, Ketchikan, and Craig, and repeater stations are few, so the effective range of the broadcast stations is only about 20 to 40 miles.

The observant will notice other subtle changes. The timberline drops, sometimes to only 2,000 feet, and the boreal mix changes. While the more southern forests are primarily composed of Douglas fir, the dominant species in Alaska are western hemlock and Sitka spruce with a scattering of red cedar, Alaska cedar, and mountain hemlock. Climax forests—old growth, where these can still be found—have smaller trees: only 200 feet tall and 5 to 8 feet in diameter. There are lots of salmonberries (similar to blackberries but colored orange to dark red), elderberries (bitter), and several varieties of blueberries and huckleberries, all in impenetrable thickets. Southeast’s forests have no poison oak or poison ivy.

Campsites in Southeast are a tad more abundant. Though vegetation remains a barrier and much of the ground is rough, the steepness of the topography eases. In a pinch, bivvy spots are plentiful. In this chapter, many potential camps are not marked—there are just too many. Some possibilities will be indicated in the text, but only definite campsites are marked on the accompanying maps.

The Alaska Panhandle is proud Tlingit country. Strong and bold enough to hold their own against most invaders, they nonetheless suffered some incursions. Oral tradition holds that, aboriginally, the Cape Fox people, of Tsimshian origin, used much of Revillagigedo Island during summers. In the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century, the Haida invaded the south end of Prince of Wales Island and successfully retained it. The Russians were even more successful, establishing settlements first at Sitka—after many setbacks and constant vigilance, a state of détente emerged in due time—and then at Wrangell. In 1887, a Tsimshian settlement, New Metlakatla, was founded on Annette Island. Eight hundred twenty-five Tsimshian, under the leadership of the Reverend William Duncan and with permission from the new US government, relocated in Alaska. They had come from Old Metlakatla, just north of present-day Prince Rupert, to escape liquor and other unhealthy influences, including—in particular—doctrinal differences with the dominant Church of England. Theirs is the only Indian reservation in Alaska.

The Route: Overview

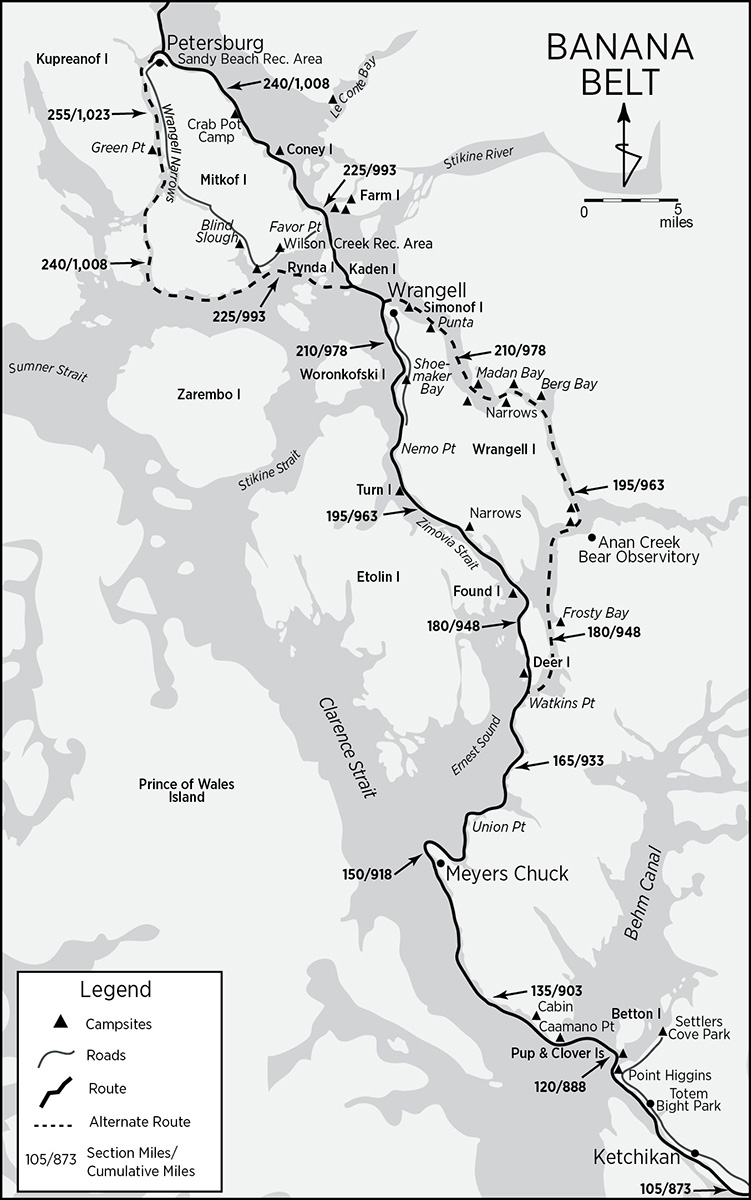

In keeping with the spirit of the oversized scale of Alaska, the panhandle section, at 382 miles, is the longest segment of this Inside Passage route. It is also, by far, the most varied. It is divided into three equal portions: Dixon Entrance, the Banana Belt, and Admiralty Island. Each one begins and ends at a major town. Both the Banana Belt and Admiralty Island portions have alternate routes. The Banana Belt section has two: one up the east side of Wrangell Island—the main route goes up the west side—and another, farther up, through Wrangell Narrows, instead of across the Stikine River delta at Dry Strait where the main route goes up. The alternate route up the Admiralty Island section goes up the mainland coast.

Dixon Entrance is not Queen Charlotte Sound; for one thing, it is only one-third as long. Outlying islands protect the route out of Prince Rupert as far as Portland Canal, the first major obstacle and the US-Canada border. At more than 3 miles in width, with only a partially—and distantly, at that—protected mouth and a 100-mile length that funnels wind and tide, the Portland Canal crossing must be carefully negotiated. Once across, the route courses up the last bit of exposed Dixon Entrance into Revillagigedo Channel and Misty Fjords National Monument, finishing up in protected waters with a clear shot at Ketchikan. Highlights include Port Tongass on Sitklan Island (an abandoned Tlingit village); Tongass Island, with the ruins of an old Customs fort; and Saxman village, a suburb of Ketchikan with a magnificent display of Tlingit life, totem poles, and a longhouse.

From Ketchikan, the route joins Clarence Strait and heads north to Myers Chuck, an endearing and welcoming tiny homesteader settlement. At Deer Island, the first of two possible alternates diverges. The main route cuts due north to Zimovia Strait and up along the west coast of Wrangell Island to Wrangell, the last Russian settlement in Alaska and home of the legendary Chief Kah Shakes. The alternate route, about 5 to 7 miles longer, courses the narrow channels between Wrangell Island and the mainland, visiting the Anan Creek Bear Observatory.

saxman native village longhouse

Wrangell sits at the southern extremity of the Stikine River delta. Although most major river deltas along the Inside Passage cause difficulties best avoided, the Stikine obstructs with little more than mostly negotiable mud and sand flats. The main route takes the shortest distance, up Dry Strait and through the barely navigable deltaic flats into Frederick Sound. The next alternate, up Wrangell Narrows, skirts the sediment flats but adds another 11 miles and follows the ferry route. Both converge on Petersburg.

Near Petersburg and up Frederick Sound, you’ll encounter the first bergy bits, calved from the Le Conte Glacier. Crossing the 15-mile-wide junction of Frederick Sound and Stephens Passage to Admiralty Island is the second crux of this leg. Fortunately, the Five Finger Island group and the Brothers Islands provide handy stepping-stones. If the Stephens Passage crossing is not propitious, you can follow the alternate route up the mainland coast past Tracy Arm and Taku Inlet to Juneau. (On the other hand, for something completely different, one could venture along the outside coasts of Baranof and Chichagof islands—a not wholly unprotected route—as Nathaniel Stephens relates in the February/March 2014 issue of Sea Kayaker.)

Admiralty Island, or Kootznoowoo (“Fortress of the Bears”), as the Tlingit called it, with a bear density approaching one bear per square mile, will give a kayaker a moment’s pause. Nonetheless, with a little bit of forethought and safe camping practices, encounters can be mitigated. A cursory glance at the map would route you up Stephens Passage. The route, however, marches up Seymour Canal. At its head some thoughtful soul has engineered and built a portage rail tramcar that artfully connects what would otherwise be a grueling 1-mile-long portage to the northern end of Stephens Passage. The Pack Creek bear viewing observatory, about halfway up Seymour Canal, is a definite objective, albeit with not a few logistical entanglements.

A final and relatively uneventful 3-mile crossing of Stephens Passage puts you at the mouth of Gastineau Channel and the outskirts of Juneau, Alaska’s state capital.

Dixon Entrance: Prince Rupert (mile 0/768) to Ketchikan (mile 110/883)

Dixon Entrance: Prince Rupert (mile 0/768) to Ketchikan (mile 110/883)

Unless you’re paddling straight through from the last section, you’ll likely arrive at Prince Rupert via car, ferry, or plane to attempt the Alaska Panhandle. If coming by plane (commercial airlines serve Prince Rupert), you’ll need to carry a collapsible kayak or have made arrangements to store your boat at the end of the last section’s trip. If you’re arriving by ferry from the south, both the BC ferry, out of Port Hardy, and the Alaska Marine Highway ferry, stop at Prince Rupert. By car, an excellent highway connects central British Columbia with Rupert.

There are three docking facilities in Prince Rupert, each one suitable for a different strategy: from southwest to northeast, Fairview Floats, Cow Bay (Prince Rupert Yacht Club), and Rushbrook Floats. Rushbrook has the only boat ramp. Arriving and paddling on through by kayak pretty much requires an overnight layover. The Cow Bay facilities may be the best alternative. Cow Bay is picturesquely and centrally located, with at least a couple of B&Bs and within walking distance of a grocery, a liquor store, a nautical supplies store, good eats, a museum, and the native cultural center. Eco-Treks Kayak Adventures (250-624-8311) is headquartered at Cow Bay and may help you get your bearings.

If you are arriving by ferry, Fairview Floats is right next door to the terminal. In spite of berthing the Prince Rupert fishing fleet, Fairview is fairly kayak friendly—just stay out of the way. Half a mile up the road are the municipal Park Avenue Campground, the Anchor Inn, and at least two B&Bs. Groceries, restaurants, and cultural activities will require a taxi ride into the downtown area.

If you’re coming by car, Fairview is also probably your best bet, with nearby vehicle storage at the Park Avenue Corner Store (FAS Gas) and the Totem Lodge Motel, both across from the campground. Considerably cheaper for long-term parking, however, is the Parkside Resort Motel, near Rushbrook, at 101 11th Avenue East.

Prince Rupert is somewhat spread out and will probably require some driving from any of the docking facilities to get this leg of the expedition up to snuff. A large Safeway and government liquor store are downtown, nearest Cow Bay, as is Smile’s Seafood—great fish-and-chips. Also located nearby are chart and navigational supply stores with Canadian government-approved capsicum bear spray for sale. Don’t miss the Museum of Northern British Columbia and the First Nations Carving Shed, where you’re likely to observe a tree trunk metamorphose into a stunning totem at the hands of an insouciant but expert carver. Both are near the Safeway.

Mileage tabulation for this section begins at the Fairview Floats. Head out of Prince Rupert toward Venn Passage, the favored route for small craft heading north. Venn Passage is subject to 3-knot currents. The stream turns about one hour before high water, so try to leave Rupert near high-water slack for a favorable current. Just before Venn Passage narrows, Fallen Human Bay, or Pillsbury Cove, indents the Tsimshian Peninsula coast. Near Robertson Point, close to the high-water line, a petroglyph known as The Man Who Fell from Heaven has been bas-reliefed on the shore rock. Pass “Old” Metlakatla, a Tsimshian village on the north shore at the end of Venn Passage. The Reverend William Duncan and some Fort Simpson area native converts founded Metlakatla in 1862. Later, Duncan and some of the natives were to relocate again in Alaska, at “New” Metlakatla on Annette Island, site of Alaska’s only Indian reservation. Opting out of the statewide native settlement, this group of Tsimshian decided to keep their 86,000-acre reservation under joint federal and native control. Round Observation Point and enter Chatham Sound.

Head up the mainland coast. North of Jap Point and in the vicinity of Tree Bluff (mile 12/780), sandy shores afford some camping. Pass Big Bay. Just offshore lies South Island (mile 18/786), a “perfect place to camp,” according to Denis Dwyer. Enter Cunningham Passage, where currents never exceed 1 knot. Stay close to shore and pass through tiny Dodd Passage for entry into Port Simpson at Stumaun Bay.

Port Simpson: Also known as Lax Kw’alaams, Port Simpson is a busy native village with water and a small grocery store. A longhouse and craft shop are visible from the floats but are not in operation. A local gillnetter informed us they’d been built for the tourist trade; however, cruise ships refuse to stop at Port Simpson.

Exit Port Simpson up into Rushbrook Passage and bear right through the small pass (Dudevoir) separating Maskelyne Island from the tip of the Tsimshian Peninsula. The southeast tip of Maskelyne Island (mile 30/798) has an excellent campsite with an abandoned cabin, a good spot from which to tackle the crossing of Portland Inlet in the early morning.

Portland Canal: Portland Canal and Inlet, 100 miles in length, is the longest fjord on the entire North American continent. For most of its course it delineates the boundary between Canada and the United States, the one exception being close to its mouth, where a few of the islands seem to be apportioned haphazardly. At Manzanita Cove on the west side of Wales Island stands one of four US Customs House cabins built in 1896 for the initial surveys of the Alaska border. When the border was determined to jog just north, through Pearse Canal, the Customs House ended up on Canadian soil. About 10 miles up the inlet, behind Somerville Island, lies Khutzeymateen Inlet, Canada’s only grizzly sanctuary. The twin towns of Hyder, Alaska, and Stewart, BC, connected to the Al-Can by the Cassiar Highway, mark the head of Portland Canal.

Portland Inlet is a productive fishing ground, usually worked by many commercial and sportfishing boats. The crossing of Portland Inlet, from either Maskelyne or Hogan Island to Tracy Island, is about 3.5 miles, or about 1 hour. Much of its mouth is open to Dixon Entrance, and the inlet can be both choppy and subject to swell. Get an early start. Since Portland Canal trends northeastwardly, some protection is afforded by crossing farther up the canal. Tidal currents can ebb at 3 knots and flood at 2 knots, though weaken somewhat at the inlet as the fjord widens. From the Maskelyne Island camp, approach the crossing up (north) Paradise Passage. If the tidal streams oppose—they can attain 3 knots—approach Portland from the west side of Maskelyne.

From Tracy Island, head for the small, well-protected channel between Boston (mile 38/806) and Proctor (mile 39/807) islands. Both sets of islands have beautiful sandy beaches with good campsites, the last ones in Canada. The border runs up Tongass Passage between Wales (Canada) and Sitklan (US) islands.

US Border Crossing: US Customs regulations require that all boats entering US waters report to the nearest Customs facility prior to any landing. The nearest Customs office is in Ketchikan, about 70 miles farther along this route. What to do? Don’t be anarchists like us and just ignore the whole procedure. On the other hand, don’t be overly conscientious. One hapless group of Inside Passage kayakers working their way north pitched camp two or three times after entering US waters and before arriving at Ketchikan. Being all good citizens, they headed for the Customs office to report their arrival. During the entry interrogation the paddlers admitted to multiple landings prior to Customs clearance. Officers confiscated their boats and gear. Only after an embarrassing newspaper publicity campaign did Customs relent. Don’t incriminate yourself. Probably the best approach for clearing US Customs is to call ahead (1-800-562-5943 or 907-225-2254), preferably from a reliable landline in Prince Rupert. Failing that, use a VHF radio via a marine operator (if you can get coverage) to communicate with either the US Coast Guard or US Customs to announce your arrival. (A 2007 blog reports that contacting the US Customs office upon arrival in Ketchikan is now an adequate procedure.)

Misty Fjords National Monument: Once across the border and nearly all the way to Ketchikan, you will be paddling in Misty Fjords National Monument. The monument was created by President Jimmy Carter in 1978 and encompasses nearly 3,570 square miles (2.2 million acres). In 1980, Congress further designated nearly the entire monument a wilderness area. The monument staff includes patrolling kayak rangers and promotes kayaking as a recreational activity. They offer maps of the monument marked with kayak-landable shores.

From the Proctor Islands, cross the imaginary border to Island Point at the south end of Sitklan Island and enter narrow Lincoln Channel. According to the Douglasses, the southernmost bight (mile 42/810) on the Kanagunut Island shore has a suitable kayak campsite. The northern bight on the Sitklan Island side is the site of the abandoned Port Tongass native village.