7

NORTHERN FJORDS

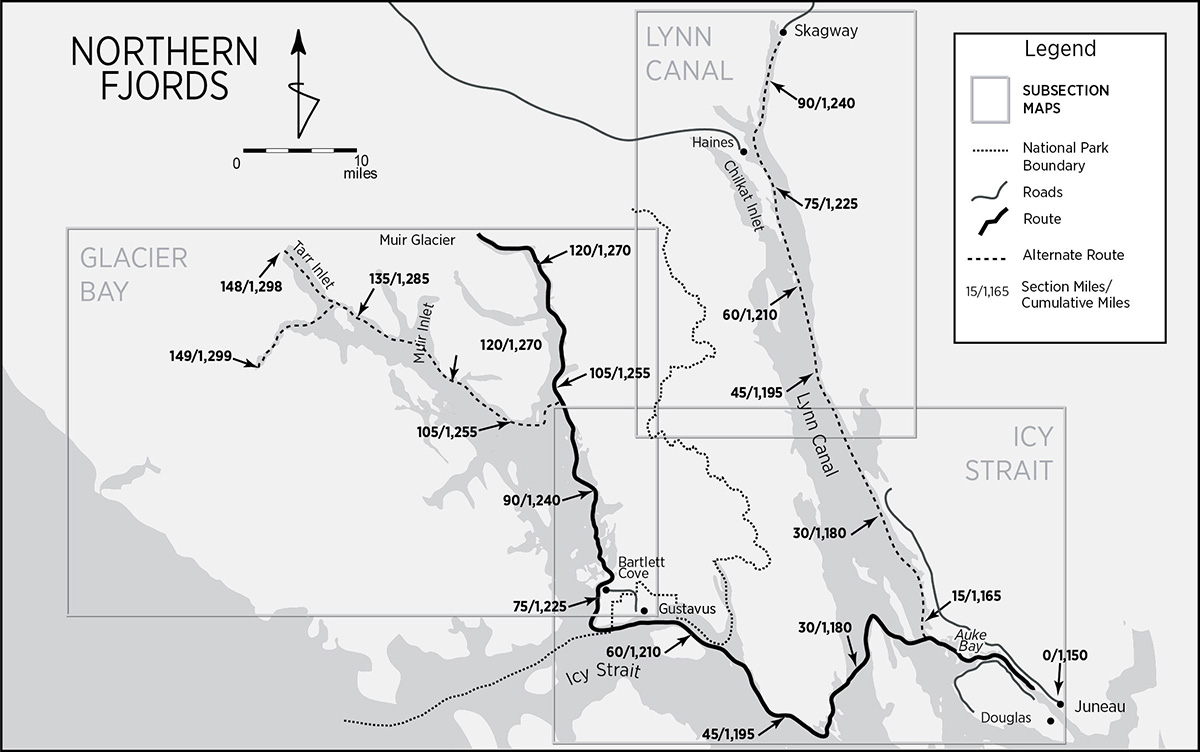

Juneau to Muir glacier, west arm, or Skagway (130/1,280, 149/1,299, 95/1,245)

Juneau to Muir glacier, west arm, or Skagway (130/1,280, 149/1,299, 95/1,245)

He who does not want to live forever

has not lived at all.

—WALLACE MILLER

Asia and America, like Siamese twins, were once joined together. Siberia-Beringia-Alaska; Alaska-Beringia-Siberia: they were all of one piece. The same life circulated throughout their river valleys and swarmed over their plains. None of the inhabitants—plant or animal—could distinguish where one ended and the other began. This lack of discrimination also dogged man, whose random wanderings populated Alaska and, ultimately, all of the Americas.

When the scalpel of climatic change separated the bodies (discarding Beringia, like some vestigial prosthesis, to the depths of the sea), subconscious atavistic links remained. Circumpolar communities, mimicking formenkreis populations, retained genetic and cultural ties that have waxed and waned with climatic variation, imperial fortunes, and the passage of time—including that anomaly in the space-time continuum, the International Date Line: Today in Alaska is tomorrow in Siberia. Lapps, Samoyeds, Tungus, Yukaghirs, Chukchis, and Koryaks have always been aware of and retained nebulous ties with the Greenland, Polar, Baffin Island, Labrador, Iglulik, Aivilik, Netsilik, Copper River, Mackenzie, North Alaskan, and Bering Sea Inuit. Not even the ham-fisted quarantine imposed by the 70-year Soviet regime could sever the yearnings of one, albeit divided, people. In any case, Soviet-imposed isolation ultimately proved transitory and was even partially overcome by the sanctioned legitimacy of an official title: the quadrennial Inuit Circumpolar Conference, which in the mid-1980s convened in Kotzebue, Alaska. Even Mother Nature feels the tug. Every year, in a vain attempt to reconnect the twins, she freezes 4 to 5 feet of the Bering Strait’s surface.

During the European Age of Exploration, Western Europe and Russia undertook uncoordinated flanking maneuvers, expanding west and east, respectively. Because the world is round, they ultimately collided in Alaska. The clash not only reconfigured relationships between the conquering powers, but also—in spite of being disruptive to the aboriginal inhabitants—forged new ties between conquerors and conquered. In some cases the new ties were of a subtle continuity. The Russians who went to Alaska were, by and large, physically indistinguishable from native Alaskans. Most were promyshlenniki, Siberian freelance traders whose physiognomy was the result of centuries of European and Siberian interbreeding. Why did Russia spread east into Siberia and, as if Beringia still existed, continue into Alaska?

The Eurasian landmass is an incomprehensibly large (it is never, ever accurately depicted on any map all at once), amorphously sprawling blob with few distinctive protuberances—Scandinavia, Iberia, Italy, Arabia, India, Malaysia, Korea, and Kamchatka are the few that come to mind—much less any natural borders immediately evident from a cursory glance at a map. Nonetheless, western convention has stubbornly—but with a nod to history and tradition—insisted on classifying this blob as two separate continents: Europe and Asia. Just exactly where does one end and the other start? Most people know that France is in Europe and Thailand is in Asia, but on what continent is Armenia, the Aral Sea, the Caspian Sea, Chechnya, or Turkmenistan? The upper portion of the western boundary between the two continents has always been the Ural Mountains, a 1,200-mile-long, north-south range along 60° of longitude. South of the range, down to the Caspian Sea, the Ural River continues the boundary. West of the Urals lies Russia proper; Siberia lies to the east. Curiously, at only 6,000 feet elevation at its highest point, and with vast, accessible lowlands on both sides of the range and the river, this “boundary” is pretty porous.

Columbus went west to reach the East. Ivan the Terrible went east to exact revenge and seek security—revenge for 250 years of Mongol and Tatar (or Tartar—Muslims from Turkestan) domination, and security (from those self-same Siberians) in the form of defensible borders. Back in the winter of 1237, Batu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, riding at the head of a disciplined horde of 120,000 men, had swept like the wind across the frozen expanses of Siberia and conquered all of Russia, penetrating as far west as present-day Hungary. The Siberians were cruel and ruthless, wreaking death and destruction and exacting tribute. Survivors—those who were caught—were roasted or flayed alive. As trophies of war, the Mongols cut off ears.

Russian resurgence was slow and disorganized. Asia had left a deep imprint. In order to beat the Easterners, Russians adopted many of their customs, not least a proclivity for absolute, cruel, and despotic rule. By 1480, Moscow’s power was secure enough that it stopped paying tribute to Siberia. In the parry and counterthrust of the Russian reconquest, many refugees fled south, out of the clutches of either Siberian or newly assertive Russian satraps. These Cossacks (from the Turkish kazak, meaning “rebel” or “freeman”), as they came to be known, retained their independence through a strict, majority-vote democracy and a warrior cult forged in self-defense and honed as freelance mercenaries.

In 1547, an extraordinary youth of 17 by the name of Ivan was crowned prince of Moscow. With the help of the Cossacks, Ivan the Terrible (his new nickname was a compliment) united all the lands of Russia east of the Urals and adopted the title czar, Russian for Caesar. But peace was not good for the Cossack economy. Possessing only the skills of war, the independent-minded southerners took to piracy on the Volga and more ambitious, entrepreneurial conquests. Under Vasily (Yermak) Timofeyevich, 840 Cossacks set out in 1581 to attack Isker, the Mongol/Tatar capital of western Siberia (from sibir, Tatar for “sleeping land” or siber, Mongolian for “beautiful,” “wonderful,” or “pure”). Czar Ivan was furious. He did not want to reawaken the dormant Mongol/Tatar Empire.

But the Mongols had gone to seed and proved no match for the Cossacks. Yermak took Isker within two years. In a shrewd move, he sent 10 percent of all the plunder—over 100,000 rubles worth, a fabulous sum in those days—as a personal gift to Ivan. Much of the booty was in furs—sable, ermine, bear, and other peltry. At the time, Russian sable commanded a princely ransom in Western Europe; in Russia, a single pelt could buy a 50-acre farm. The czar responded by pardoning the Cossacks for all their crimes, decorating Yermak, promising reinforcements for further conquest, and creating a special, privileged regiment, the Siberian Cossacks. To keep the riches flowing, he also guaranteed the promyshlenniki unfettered access to Siberian resources in return for a 10 percent portion. The Russian conquest of Siberia had begun.

Czar Boris Godunov, who succeeded Ivan in 1584, continued the eastward expansion. In 20 years, western Siberia was held by a line of forts stretching from the Arctic to the highlands bordering the northern verges of the Manchu Empire. Furs, plunder, revenge, and expediency drove the onslaught, with no small part played by the decline of Mongol/Tatar power. Finally, 405 years after his forebears had conquered Russia, Altyn Khan, heir to the throne of Ghengis, announced he was ready to submit to the Czar and become a vassal of Moscow.

By 1632 Russians reached the Lena River and established redoubt Yakutsk. Yakutsk’s commander soon dispatched a 20-man mounted regiment under Ivan Moskvitin to see what lay beyond the Stanovoi Mountains to the east. In 1639, Moskvitin—the Cossack Balboa—reached the Sea of Okhost, northern terminus of Asia’s Inside Passage, a much less protected waterway between Japan, the Kuril Islands, and the Kamchatka Peninsula. Siberia, a distance of 5,800 miles, had been conquered in 60 years.

Russian expansion was not just due east. Cossack adventurers soon set their sights on Mongolia, China, and Manchuria. Success bred overconfidence and arrogance. In 1658, Russia reached for China. For the first time since their arrival in Asia, the Russians met with thorough defeat at the hands of a Manchu army that numbered 10,000. But China had no wish to arouse a permanent enemy. In a shrewd move that neutralized any further military adventurism, China opened its markets to Russian furs and introduced the would-be conquerors to a new addiction: tea. The policy proved admirable: peace and commerce broke out along Siberia’s southern border.

Although Russians had reached the Pacific, no one knew—or seemed to care—whether Asia and America were connected. Not even the man entrusted to ascertain the facts, Vitus Bering—a plodding and incurious but brave and determined (and tactful and kindly to boot; qualities that kept this and subsequent expeditions from total meltdown) Dane—cared much about the mission entrusted to him by the one man who did care. In 1689, a 17-year old, 7-foot giant of a man with a will and a vision to match had ascended to the throne of Muscovy. Peter the Great weaned himself on the acquisition of knowledge and was consumed with pushing the frontiers of science. In 1719 he had dispatched a two-man expedition to settle the question. The modest enterprise fell short of the challenge. Five years later, on the advice of his admiralty, he commissioned Bering to settle the matter once and for all. Unfortunately, Peter died the following year and was succeeded by his widow, Catherine I.

Bering had his hands full. Russia’s single Pacific port, Okhost (built by Moskvitin’s Cossacks), wasn’t much more than a handful of log buildings with a wharf, ice-locked for six months and fog- or storm-bound the rest of the time. To reach Okhost, Bering first had to get to Irkustk—in itself no mean feat when setting out from St. Petersburg. Out of Irkutsk, the first 1,500 miles down the Lena River to Yakustk was traversed by boat or horse, depending on the season. Next came the difficult part: 700 miles and multiple 4,000- to 5,000-foot climbs across the Stanovoi Mountains. Reindeer were drafted. Since iron was scarce, dozens of horses had to haul the anchors and metal rigging for the boats that still had to be built.

In the fall of 1727, after a year and a half of traversing Siberia, Bering arrived at Okhost, where he spent the winter preparing for the next leg of the journey. The following year he sailed 600 miles across the Sea of Okhost to the Kamchatka Peninsula. There he dismantled necessary supplies for the trek across that godforsaken appendage—about the size of Italy—to the side facing America, where he founded Petropavlovsk, his forward base of operations. In July of 1728, he finally launched the St. Gabriel. It was a short mission. Although he determined that Asia was not connected to America, in the process lending his name to that buffer of water, he never saw America. Bering’s 1730 report to the Moscow Academy of Sciences served only to whet the appetites of the admiralty, Czarina Catherine, and Bering himself. At its conclusion he proposed another expedition.

Three years later he found himself leading 900 people in “the largest expedition of its kind ever undertaken by any European government for the purpose of scientific and geographical research up to that time.” Its remit was staggering. First, small subsidiary salients were to explore and map the entire Arctic coast from St. Petersburg to Bering Strait; ditto for the Pacific shore from Bering Strait down to the Amur River. Third, another subsidiary command was to explore the archipelago south of Kamchatka (the Kurile and Sakhalin islands) to Japan, claim everything that it could, and establish trading relations with the Japanese.

Bering himself led the fourth contingent of the Great Northern Expedition, as the entire enterprise came to be called. This was to establish Russian sovereignty on the American Northwest Coast. To conceal its true purpose from rival powers, the expedition was cast as a follow-up attempt to determine whether Asia and America were joined—the first attempt having failed. Expedition members were under special instructions “for public display” to that effect and had been sworn to secrecy. Bering had been under no misgivings about the nearness of America during his first voyage. When he turned back, in spite of not actually seeing America, he knew it was there. The signs were all evident: shorebirds, coastal fog, shallow waters, green driftwood and grasses, littoral echoes, and continental shelf currents. The last objective of the Great Northern Expedition—led by a 600-man-strong contingent from the Academy of Sciences—was to catalog the plants, animals, minerals, and ethnic tribes of the new lands.

After eight years of preparation and travel across Siberia, Bering once again found himself in Petropavlovsk. This time he embarked in two newly built boats, the St. Peter, under his command, and the St. Paul, under Aleksei Chirikov. On July 16, 1741, after weeks of wandering in the fog and losing Chirikov, Bering finally saw the mainland of America. The clouds parted dramatically, and there, bathed in god-light, stood the awesome peaks of the St. Elias range. His work, he prematurely concluded, was done. Tired, burned out, and worried no end about food, safety, and the weather, Bering was ready to go home. Georg Steller, the expedition naturalist, however, prevailed on him to make landfall at least to fill water casks, collect specimens, and contact the inhabitants.

But bad weather kept the St. Peter offshore. Attempting both to make homeward headway and make landfall in the new land, Bering ended up zigzagging back along the Aleutians where, on Bird Island, he finally met Americans. The meeting was anticlimactic and was characterized by misunderstanding and hurt feelings—on both sides. Bering never reunited with Chirikov. Only 115 miles short of Kamchatka, her crew weakened by constant storms and scurvy, the hapless St. Peter shipwrecked on an uninhabited island that was to bear Bering’s name and become his final resting place.

Meanwhile Chirikov, commanding the St. Paul, beat Bering to the punch by discovering Alaska—in the form of Prince of Wales Island—on July 15, 1741, one day before Bering’s sighting. A few days later, he dispatched 11 armed men with a Koryak interpreter and trade trinkets in the ship’s longboat up Lisyansky Inlet, near modern-day Pelican on Chichagof Island, to contact the natives. Both the men and the boat disappeared. Chirikov waited five days but saw none of the prearranged, agreed-upon distress signals—only a blaze that grew bigger. Thinking that the longboat had perhaps been damaged, he sent the boatswain in the one remaining yawl with a carpenter, a caulker, and a sailor. The second boat also disappeared, followed by another bonfire.

Later on, two natives paddled out from the bay, shouted something twice—while still at a considerable distance—and paddled back to shore. Chirikov tried to entice them back and lingered for another day. But without shore boats to replenish dwindling supplies and water, Chirikov reluctantly weighed anchor and headed for home, abandoning his missing men to their fate. To this day, Tlingit lore in the Pelican area proudly boasts of this ruse.

The St. Paul also worked its way back to Kamchatka along the Aleutians, successfully trading with the Aleuts and even getting them to convey fresh water in bladders. They arrived at Petropavlovsk on the 10th of October.

Russia went to Alaska to ensure no part of Asia was overlooked and even—in a final blaze of hubris—to take its place among the world’s powers by staking an American claim. Time, distance, Arctic waters, and the final containment of the Mongols; scurvy, starvation, and disorganization; and the death of the driving forces behind eastward expansion, Peter and Catherine, stopped the Russian advance. Bering’s death prior to his return and the loss—in typical Russian fashion—of his logbooks, charts, and reports into the abyss of provincial archives put the final nails in the coffin of the entire enterprise. Czarina Elizabeth, Peter’s beautiful but intellectually challenged daughter—who wanted no part of statecraft—succeeded Catherine and, through active neglect, terminated all further official eastward progress. Russia was whole; America no longer fit neatly into the picture. So why did Alaska still end up in the Russian embrace? Other, more fundamental forces—greed and opportunity—were already at work, unfolding an entirely new scenario.

Parallel to official history, unofficial history was also taking place. For example, the Bering Sea ought to have been called the Dezhnev Sea. True to traditional Russian bureaucracy and disorganization, the question of whether Asia and America were connected had already been settled as far back as 1648, 80 years before Vitus Bering. Only no one had as yet bothered to formulate, much less ask such a question. A band of Cossacks under Semyon Dezhnev—investigating possible commercial prospects, of course—had sailed down (north) the Kolyma River in willow boats into the Arctic Ocean and rounded Siberia’s eastern tip to the mouth of the Anadyr River, a voyage of 2,000 miles. Their report, however, never made it to St. Petersburg, having been buried in the local files at Yakutsk. Dezhnev, after retiring to Moscow, was himself unaware of the import of his discovery. Today, Siberia’s easternmost salient is named Cape Dezhnev to commemorate the Cossack. Never mind; in Russia, scuttlebutt ruled. On that venture, the Cossacks had encountered wonderful new creatures—fur seals and sea otters—the latter with a pelt that outshone even the sable for richness and beauty. Promyshlenniki swarmed to exploit the new commodity—prematurely. Neither animal was common off Siberia, and no bonanza was realized. But a few pelts found their way to China, where they commanded exorbitant prices. A seed had been planted.

Likewise it was neither Bering nor his subordinate Chirikov who “discovered” Alaska. In a classic example of one hand being unaware of the doings of the other, the Supreme Privy Council had authorized a military expedition, under Afanasy Shestakov and Dmitry Pavlutsky, to consolidate Russia’s hold over the entire northeast salient of Siberia by pacifying the rebellious Koryaks and Kamchadals. After much cruel slaughter—including the death of Shestakov—and a series of face-saving treaties, Pavlutsky decided to do a little exploring and search for the “Great Land,” rumored to lie close off the Chukchi Peninsula. He appropriated Bering’s St. Gabriel—after all, it was between voyages and unemployed—for the task. In command he placed Mikhail Gvozdev with a crew of 39 men. According to Benson Bobrick, in East of the Sun: The Epic Conquest and Tragic History of Siberia:

Sailing from the mouth of the Anadyr in July 1732, they paused briefly at one of the Diomede Islands, and then continued eastward, apparently coming within sight of Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska. Drawing near, they saw that it was quite large and covered with forests of poplar, spruce, and larch. After skirting the coast for several days, they found “no end in sight.” At one point, “a naked native paddled out to the vessel from shore on an inflated bladder,” and through their interpreter asked them who they were and where they were going. They replied that they were lost at sea and were looking for Kamchatka. The native promptly pointed in the direction from which they had come. They did not make a landing, however, and because after their return they failed to collate their notes and make an adequate map, their voyage did not come to official attention until a decade later, in 1743. By then the priority of their discovery had become a technicality . . .

So there you have it: Vitus Bering discovered neither Bering Strait nor Alaska. But he did put them on the map.

From Bering’s second voyage, Chirikov had returned without incident; Bering, on the other hand, weakened by scurvy and early winter storms, shipwrecked on Bering Island, part of the Commander Group, in 1741. Bering never recovered. The survivors subsisted through the winter on the abundant wildlife. The following year, they built a boat from the wreckage and sailed into Petropavlovsk wretchedly but triumphantly gowned in blue fox, seal, and otter furs. The 900 sea otter pelts they managed to bring back proved more than enough to have paid for a quarter of the cost of the entire expedition from the time it left St. Petersburg. The fur rush was on.

Frenzy gripped the Kamchatka garrisons. Yemelian Basov, sergeant of Cossacks at Nizhnekamchatsk, was possessed. He immediately raised capital for a fur-hunting venture, rounded up a crew of 30 promyshlenniki—working on shares—built a flat-bottomed river scow, the Kapiton, and set off for Bering Island in the fall of 1743. He succeeded beyond his wildest dreams and returned for a second, third, and fourth winter. The number of skins from the second year alone totaled 1,600 sea otters, 2,000 fur seals, and 2,000 blue fox.

In no time, the little Commander Group’s fur-bearing population was close to exhaustion, so the Russians sailed farther east, to the Aleutians. On September 25, 1745, the promyshlenniki landed on Agattu and encountered Americans for the first time. One hundred dancing Aleuts greeted the Russians. The meeting did not go well. Misunderstanding led to overreaction, and at least one native was shot dead. A separate encounter, on Attu, took place at Massacre Bay, where the Russians took advantage of Aleut hospitality by raping a number of women and slaughtering the men who came to their aid. Unofficial Russia had arrived in Alaska, though it would take another 18 years for them to methodically work their way up the Aleutian chain.

For the next 122 years, Russia continued its eastward expansion into Bolshaya Zemlya, the Great Land, as they had renamed the Aleut’s Alaxsxag, which means “the object toward which the action of the sea is directed.” As a colonial venture, the entire enterprise was without parallel. For one, it was the world’s most distant colony, at 9,000 miles from St. Petersburg to its first “capital” at Three Saints Bay, on Kodiak Island. Alaska had no strategic significance; it was not a refuge for dissidents; there was no scramble for empire; religious conversion was not a factor; riches for state coffers played no part. Government offered no support and even washed its hands of the whole matter. Ragtag individual and undercapitalized collective entrepreneurs, impervious to hardship, unsophisticated—often psychopathic—yet maudlin, wild-eyed, and superstitious with traces of mysticism, pushed into the new land with only one objective: furs for the Chinese market, which they forced the Aleuts to hunt.

It would be years before St. Petersburg recognized its illegitimate offspring. And the response would always be too late, usually inadequate, and lacking in proper supervision. A few lucky twists of fate tempered and redeemed the entire undertaking. The eventual depletion of sea otters, uncooperative geography, and Tlingit resistance contained the Russians. De facto governor Alexander Baranov’s able administration transformed a potential Lord of the Flies nightmare into a passable colony.

But true civilization was absent until the arrival of Reverend Ivan Veniaminov, later to become head of the Russian Orthodox Church and canonized St. Innocent in 1979. The prelate singlehandedly transformed Russian-native relations from adversarial to cooperative, introduced the norms of civil society to the hintermost frontier, and recorded more scientific data—in ethnology, linguistics, meteorology, and the natural sciences—than all previous attempts.

Even so, Alaska remained a bastard child. The colony was indefensible, numbered fewer than 800 Russians, and was a drain on the Treasury. If prospectors from the California gold fields or Mormons fleeing persecution were to invade Alaska, St. Petersburg risked losing all control. After Russia’s 1857 defeat at the hands of the British in the Crimean War, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs floated the possibility of the colony’s sale. The sale would help to pay war debts; consolidate Far Eastern territories; cock a snook at the British by nearly doubling the landmass of the United States, Britain’s rival in North America; and forge an alliance with that promising, up-and-coming power. The American Civil War, however, put the deal into deep escrow.

Confederate raids on American whaling ships in the Bering Sea convinced Secretary of State William H. Seward that a US Navy presence in the region was imperative. Emperor Alexander II and President Andrew Johnson had both come round to favoring the deal. Russian and American popular sentiment, however, were against the transaction. Alaska was soon referred to as Seward’s Icebox, and a skeptical Congress was loath to consider or approve it. Nonetheless, when Eduard Stoeckel—the Russian diplomat empowered to pursue negotiations—and Seward met in March of 1867 to discuss trading rights, Seward popped the question: Would Russia consider selling Alaska outright?

Stoeckel had been authorized to accept $5 million. But the cagey negotiator played his cards well and responded noncommittally. When Seward offered $5 million, Stoeckel countered $10 million. They soon settled on $7.2 million. The formal transfer took place at Sitka on October 18, 1867.

There are striking geographic and developmental similarities between the two twin landmasses. Dual river systems—the Kolyma and Indigirka watersheds in eastern Siberia, and the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers in Alaska—drain their central vastnesses. And both face off nose-to-nose at the Chukchi and Seward Peninsulas. Developmentally, Siberia’s fur rush overflowed logically and directly into Alaska. But by the time of the sale, both Siberia’s and Alaska’s fur resources were running short, and a new mother lode displayed bright potential: gold.

The discovery and exploitation of the yellow ore unfolded in radically different ways along the river valleys of the now even more separated twin landmasses. Gold had been discovered at Nerchinsk and along the Lena and Yenisey river valleys in the early 1800s. It was at first a state monopoly, but by 1836 private prospecting and mining operations became legal. The gold, however, could only be sold to the state. In contrast, neither the US nor the Canadian governments placed any constraints on the Inside Passage’s gold strikes. Every prospector could keep all of his sweat-gotten gains.

Predictably, the mines developed at different times—this time Siberia lagging behind Alaska—and along somewhat different philosophies. By 1904, the last big strike, at Fairbanks, had played out, and although gold mining continues today, it plays a decreasing role in Alaska’s economy. Siberia’s geologically analogous gold deposits were exhumed at much greater cost. Never a populous place, far eastern Siberia was peopled by a handful of indigenous natives, adventurous Cossacks, opportunistic freelance traders, and—after 1825—political convicts and exiles. During the 1917 Russian Revolution and the civil war that followed it, anti-Bolsheviks of all stripes went to Siberia to escape persecution. Many surreptitiously took up prospecting. After the civil war, Lenin, to rebuild the country and nurture the shattered economy, legalized free enterprise and declared an amnesty.

Prospectors poured in. In 1910, gold was discovered along the Kolyma River but, due to political and social upheavals, nothing much came of it. By the late 1920s, substantial quantities of gold were being mined, and, in conjunction with the new mother lode along the Indigirka River, the Kolyma fields were proving to be the equivalent of a Soviet Alaska. Inevitably, the new government was soon perched on the horns of a dilemma. It could either continue tolerating free enterprise and miss out on the bonanza, or nationalize the resource and invest a great amount of capital in the development of the area. The first option was anathema for political reasons—after all, the Bolsheviks were trying to establish Communism. Only nationalization was left. However, there was no capital available. Josef Stalin, Lenin’s successor, decided to “invest” the one resource the government could dispose of: human beings.

In 1931, the Far Northern Construction Trust, Dalstroy—an early subsidiary of the Glavnoe Upravlenie ispravitel’no trudovykh lagerei, or Gulag (Chief Administration for Corrective Labor Camps)—was set up and began preparations for a major gold-mining enterprise. Soviet propaganda even depicted the basin as a sort of Russian Klondike. Dalstroy’s first miners were “excess” peasants from the Ukraine, victims of the collectivization of Soviet agriculture. Many more miners would follow. During the mid-1930s, Trotskyists, Social Democrats, Mensheviks, anarchists, and members of other left-wing organizations were shipped east to take up pick and shovel. In 1937, purged Communist Party members were reassigned from their desks to gold mining in the Kolyma and Indigirka fields. Two years later, when the USSR and Germany invaded Poland and the Baltics, most prisoners of war were redeployed to mine gold. When Hitler turned on Stalin in 1941, all Russians of German extraction were relocated to Siberia. Some ended up gold mining. But the cruelest, most ironic gold-mining assignment came after the war. To cleanse all possible ideological contamination, every Russian soldier who had spent time as a POW of the Nazis made the obligatory trek east for reeducation through gold mining.

At first, the policy was to produce gold efficiently; after 1937, the policy was to eliminate prisoners—through exposure, disease, exhaustion, and starvation. More than 3 million perished in the Kolyma-Indigirka gold mines alone. The Kolyma fields, a total of about 80 mines, produced 3,300 tons of gold over the course of 22 years. By comparison, Alaska’s gold rush era—from 1880 to 1904—lasted 24 years. One conservative estimate is that every kilogram of gold cost one human life. With Stalin’s death in 1953, conditions slowly improved. After the fall of Communism and breakup of the Soviet Empire, the remnants of Kolyma and its capital, Magadan, were preserved in memorials, museums, and restorations—like some grotesque cross between Auschwitz and Skagway—to bear witness for future generations.

Natural History

George Vancouver did not encounter Russians until his survey of the Northwest Coast was nearly complete. Following the strategy espoused by this book, Vancouver undertook the survey over the course of more than one season, wintering in the Hawaiian Islands between charting explorations. In the first year, 1792, he got as far north as Bella Bella, British Columbia. The following year he reached a point near present-day Petersburg, Alaska. In 1794 he took a different tack. Starting in Cook Inlet, Vancouver decided to work his way south to his previous point of completion. Straightaway he ran into Russians. Vancouver noted that they were thoroughly absorbed in the fur trade. The Russians had not yet founded Sitka and had settled only as far east as Kodiak Island. Hoping to meet and pay his respects to the Russian-American Company’s new manager, Vancouver paid a courtesy visit. Unfortunately he missed him. Alexander Baranov, who had arrived a scant three years earlier, was off consolidating his new charge.

Vancouver reentered protected waters at ice-choked Icy Strait, the northernmost entrance to the Inside Passage. He never saw Glacier Bay. Not that he missed it: Glacier Bay did not exist. Although the entrance—a 6-mile bight backed by a several-hundred-feet-thick glacier reaching back into the mountains—was there, in 1794 the rest of the bay lay entombed under a mile-thick shroud of ice.

Therein lies the wonder of Glacier Bay National Park. In the first 120 years since Vancouver’s visit, Glacier Bay’s ice cap retreated 65 miles, uncovering a new land. The rate of recession was phenomenal and unprecedented. Never in recorded history has a glacier retreated as fast as the one that filled Glacier Bay. Then, all of a sudden, the glaciers stopped. By 1916, the Grand Pacific Glacier at the head of Tarr Inlet settled more or less where it holds court today. Though some glaciers still recede and some grow—and exactly what they will do is the subject of much study and speculation—nature suddenly imposed a rough equilibrium. The glaciers’ maximum 2-mile-per-year retreat during the bay’s formative years had ceased. It was during this time, in 1879, that John Muir “discovered” Glacier Bay. Only 85 years had elapsed since Vancouver’s passing. In that short time the ice had retreated nearly 50 miles. Muir was spellbound. He built a cabin at Muir Point near the glacier that now bears his name, returned for three more visits, and added his efforts to the preservation of the bay.

Glacier Bay hasn’t always been covered with ice. Tlingit oral tradition recounts a time when the invasion of the glaciers drove the inhabitants out. At times, that glacial advance was almost but not quite as phenomenally fast as the later historical retreat. A variety of evidence indicates that, prior to 2,000 BC, Glacier Bay looked much as it does today. Then, during the Little Ice Age, the ice girded its loins and rumbled south. A thousand years later, it trapped remnants of the old forest in graveyards of ghostly deep freeze. These copses of interglacial wood are still visible along Muir Inlet. During the reign of Peter the Great, Glacier Bay’s Tlingit were under siege. They cut their losses, retreated, and relocated across Icy Strait at present-day Hoonah. By the mid-eighteenth century, the wall of ice was 20 miles wide, a mile thick, extended more than 100 miles back to its source in the St. Elias Range, and protruded into Icy Strait.

Glacial advances and retreats did not begin 4,000 years ago. Prior to the Little Ice Age, many advance and retreat episodes punctuated Alaska’s—and the entire world’s—history interminably back into the fog of time. Besides the four major Pleistocene ice ages, glaciologists have indications that the earlier Pliocene was also peppered with glacial epochs. Barring unforeseen circumstances, the cycle will continue. As of 2017, most of the park’s tidewater glaciers inside the bay were receding. Only two are advancing: Johns Hopkins and Lamplugh, both in the West Arm.

When a fat man rises from a waterbed, the mattress rebounds to its old shape. So it is with the land. During the years of the last glacial retreat, when the enormous weight of the ice was lifted from Glacier Bay, the land—depressed for so long—immediately began to rise. The rate of rebound—isostatic compensation—is astonishing. In the Bartlett Cove area, the land rises 1.5 inches per year. Kayakers navigating with USGS topographic maps soon discover that some waterways are now blocked, or at least require a high tide for passage, or even a short portage.

As the glaciers retreat and the land rises, it also reawakens. Algae are the first colonizers of the bare rock, gravel, and glacial till exposed by the ice. Mosses, sedges, grasses, dwarf fireweed, and dryas, with its ability to fix nitrogen, then get a toehold. In 30 to 40 years’ time, willows and Sitka alder take over, reaching heights of 10 feet and thoroughly blocking human access. Where there’s enough nitrogen and sun, cottonwoods and willows set down roots. But the alder thicket is so effective at blocking sunlight that it keeps most seedlings—including its own—from propagating and prevailing. The exception is Sitka spruce, which thrives in the shaded conditions. Eventually the spruce take over and create a true forest. Finally, the plant succession cycle reaches a climax—a more or less balanced and self-sustaining population of final species—when western hemlock predominates.

Bartlett Cove, ice-free for 200 years, nestles in a mature hemlock-spruce forest community. To travel up bay from the park headquarters is to travel back in time through the plant succession cycle. North of Bartlett Cove, hemlocks progressively thin. Beyond Mount Wright, spruce become rare; alder and willow thickets prevail. At the heads of the distal bays and inlets, glacial snouts root into morainal troughs devoid of any plant life.

Glacier Bay exuberates with animal life. Humpback—and, to a lesser degree, minke—whales are common. Luckily for the pinnipeds, orcas don’t often wander in too far. Around the Marble Islands in midbay, the cacophony of endangered Steller sea lions is audible for miles. Curious to a fault, they will investigate kayakers. Harbor seals concentrate on ice floes off the face of glaciers in the spring to bear pups. Don’t spook them.

More than 200 species of birds have been sighted in the park. Besides the more common ravens, eagles, gulls, grebes, loons, terns, and cormorants, you’re likely to see busybody pigeon guillemots; comical oystercatchers with their distinctive orange bills; murres and murrelets; kittiwakes; sometimes-confused phalaropes, sandpipers, and yellowlegs; tentative plovers and turnstones; and elegant tufted puffins and harlequin ducks, kabuki characters in a maritime pageant. Many of these species have communal nesting sites on islands and in the upper reaches of the park. Don’t freak the birds. Ptarmigan, for as dim-witted as they seem to be, are not uncommon.

Moose entered the park in the 1940s and can usually be spotted along the eastern shore, particularly in the Beardslee Islands. Mountain goats and marmots populate the more recently unglaciated areas, feeding on grasses, shrubs, and buds. Black bears are common in the vegetated areas; grizzlies less so, preferring the upper and northern barren grounds.

Within the park, bear management is exceptionally effective. Park regulations require backcountry users to store all food in bear canisters. These are provided free of charge. Observe all food storage and preparation guidelines to ensure both the safety of the bears and that of future visitors. Firearms are not allowed. Respect the areas that are closed due to exceptional bear activity. Bears that acquire bad habits are soon banished; visitors responsible for those bad habits are held accountable.

Much of Glacier Bay National Park is true wilderness, although within the park along this route you’ll probably encounter more kayakers than in any other portion of the Inside Passage save for the Robson Bight, San Juan, Gulf Islands, and Puget Sound sections. Private motorized vessels are strictly limited; more common are tour boats, including the park concessionaire’s cruisers.

Even outside the park, glaciers are never far away. To the north and east, the ice caps of the St. Elias and Coast Ranges encircle the straits and inlets of the upper Inside Passage. No doubt this contributes to the sense of community that predominates among giant Juneau and its smaller neighbors nearby: Douglas, Mendenhall, Auke Bay, Haines, Skagway, Hoonah, Gustavus, and Elfin Cove, all held together by ferry services, floatplanes, fishing and cruising craft, as well as two road connections to the outside world. With all the traffic, cabins, and evidence of logging, you never feel you’re too far off the beaten path, either on the approach to Glacier Bay or up Lynn Canal, the oldest of the northern fjords and historic terminus of the Inside Passage.

Though replete with nontidewater glaciers, Vancouver found Lynn Canal navigable and named it after his home town of King’s Lynn, Norfolk. Today, the glacial retreat is much advanced here, and the biotic recolonization—in spite of the 4,000-foot alpine walls—advances unhindered. Much of the land along Lynn Canal has risen 400 to 500 feet since the last ice age. It is North America’s longest and deepest fjord. Once the weight of the ice was removed, the land began rising and continues to do so, with Haines going up at the rate of 18 inches per century.

Lynn Canal is full of wildlife. Moose have been invading from Canada ever since the ice retreated. It is also thick with humpback whales feeding, usually preceded by a series of five shallow dives and exhalations, followed by a pronounced humping of the back with a fluke flourish and a deep dive. Rarer is bubble-net feeding, where a pod encircles a school of fish for collective hunting. If you’re ever likely to see bubble-net feeding, this is the place. We saw over 10 whales every day during the six days in late July that we ran to Skagway. During the pink/humpback run, salmon too are so thick and—perhaps practicing for their upstream marathon—jump so often that one whipped right into the author’s cockpit! Luckily the sprayskirt trampolined her out of my lap, precluding any serious damage to either of us. With the Chilkat River supporting all five species of salmon, paddlers are likely to encounter salmon anytime between April and November.

And the salmon attract eagles. The 48,000-acre Chilkat Bald Eagle Preserve outside Haines hosts the largest concentration of bald eagles in the world, swelling to 4,000 in the fall and winter. According to Stephen Hilson:

Eagles have been observed sinking their sharp talons into large salmon in mid-stream only to find themselves unable to lift the fish into the air and were forced to swim to shore clinging to their heavy prize. The big birds have also been seen making mid-air passes with their meals, carrying a salmon to a high elevation and releasing in mid-air only to have it caught in the talons of a low flying friend.

Tides in the far reaches of the northern fjords can rise 25 feet, though few places are plagued by extreme currents. Be mindful when beaching boats on gentle shores—the rate of rise is deceptive.

Lynn Canal, due to its north-south orientation, funnels south winds with a vengeance, particularly near Skagway (from skagua, Tlingit for “windy place”). Don’t be misled by Haines/Skagway weather predictions of 15- to 20-knot winds with 3-foot seas, or confuse such detail for accuracy. These are often default forecasts that may translate, due to the funneling effects just before Skagway, into 35-knot (or greater) winds with shearing, tight chop. With few places to land, such serious conditions can be a nightmare for kayakers. Again, mornings are generally calm, with winds building up after noon.

The inappropriately named Fairweather Range grabs every passing low pressure system, nearly draining them of moisture to feed its glaciers and inundating Glacier Bay with 75 inches of annual rainfall at Bartlett Cove. In contrast, Lynn Canal, 70 miles farther east, is in the range’s rain shadow: Haines and Skagway only get about 48 inches of precipitation.

Lynn Canal is home to Klukwan (population 111), the oldest continuously inhabited community along the Inside Passage and home to the historically largest and most powerful Tlingit village-state (the name means “the old town”). Also known as the Chilkat Indians, they controlled and jealously guarded all trade through Chilkoot Pass, one of the few practical routes to the interior. Hilson recounts:

Finally, in 1880 the first agreement was worked out enabling a group of white prospectors from Sitka to enter the interior via Chilkoot Pass. Led by Edmund Bean, the men agreed to refrain from trading with the interior Indians and would not carry alcoholic beverages. It wasn’t long before a white trader broke the agreement and trouble erupted.

On June 4 and 5, 1888 the Chilkat and Sitka Indians got into a dispute over whether or not the Sitka people had a right to pack miner’s equipment over the trail. Chilkat chief, Kla-Naut, demanded a 30% commission on the Sitka’s earnings. The Sitka leader, Sitka Jack, adamantly refused and a fight developed in which Sitka Jack killed Kla-Naut by clubbing the chief with his riffle butt and then died from a stab wound inflicted by Kla-Naut’s teenaged son. Other men became involved, many of whom were killed or wounded.

The steamer Lucy was sent out from Juneau to prevent more bloodshed. However, by the time the 22 armed deputies arrived on the scene (June 9), the skirmish had ended. Both groups continued packing supplies on the trail.

The Route(s): Overview

On the last—and (by a smidgen) shortest—section of the Inside Passage, you have the choice of three possible final destinations. The first is Alternate Route #1—the historic route up to Skagway (95 miles). The other two routes reach to the ends of Glacier Bay: the Main Route—up Muir Inlet (130 miles); or Alternate Route #2—up Glacier Bay’s West Arm (149 miles). The Main Route is subdivided into two portions: Icy Strait and Glacier Bay. Each of the alternate routes is described at its point of departure.

The first portion of the main route, out of Juneau, uncharacteristically runs 77 miles due west and courses along private land, more of Admiralty Island National Monument, and lots more of the Tongass National Forest. Juneau and its suburbs, along tricky Gastineau Channel, dominate the first 15 miles. Another 20 miles up Stephens Passage and down Lynn Canal—around the northern tip of Admiralty Island—puts you at the eastern end of Icy Strait. Just before the entrance to Glacier Bay National Park, you pass Gustavus, the only town along the route. The first portion of the main route ends at Bartlett Cove, park headquarters.

The last portion of the main route, entirely within the park, heads due north for the final 53 miles of the Inside Passage: up Glacier Bay through the Beardslee archipelago and all the way to the head of Muir Inlet, past the McBride and Riggs Glaciers to Muir Glacier—the ice field that made Glacier Bay famous. Though all three are now receding, they are more or less all tidewater glaciers.

The first alternate route, to Skagway, diverges from the main route at mile 13. The successive 82-mile run to Skagway up through Favorite Channel, Lynn Canal, Chilkoot Inlet, and Taiya Inlet is bordered by Tongass National Forest and substantial chunks of private property. There are three middling crossings. Both Haines (the only other town along the route) and Skagway are well connected to the outside world by air, ferry, and a paved highway fully integrated into the North American grid. Additionally, Skagway retains its historic White Pass & Yukon Route Railway and is the access point for both the Chilkoot and White Pass National Historic Trails into the Yukon.

The second alternate route, up the West Arm of Glacier Bay, diverges at Garforth Island, mile 102. The West Arm was formed by Glacier Bay’s two advancing tidewater glaciers, Lamplugh and Johns Hopkins. Both calve a prolific number of icebergs into the sea, as does stable Margerie Glacier at the head of Tarr Inlet, giving the impression that it too is advancing. Here too is the largest ice field of all, the Grand Pacific Glacier. Unfortunately, black with morainal debris, thinning and receding, its impression is somewhat underwhelming.

In contrast to ending the Inside Passage at Skagway, finishing up in Glacier Bay presents a few logistical problems that are best addressed before embarking from Juneau. From the heads of Muir, Tarr, or Johns Hopkins Inlets, you must unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on your perspective) retrace your route back to Bartlett Cove in order to connect with public transportation for the return home.

The obvious first solution is to paddle back to Bartlett Cove from your preferred end run. If an additional 50- to 60-mile plus paddle from the head of Muir Inlet or the West Arm back to Bartlett Cove—after kayaking the entire Inside Passage—is more than you can stomach, take heart. The Glacier Bay tour concessionaire makes daily runs to the mouths of both inlets and, with or without advance reservations (better with!), will conveniently pick you up and shuttle kayaks and kayakers back to park headquarters. But you’ll still have to paddle back from the heads of the inlets to the pickup locations. Just make sure you know exactly where these spots are, as they change every year.

Getting from Bartlett Cove to Juneau with your kayak depends on what sort of kayak you have—hard-shelled or collapsible—and whether it’s a rental boat (and to where the rental must be returned). With a collapsible boat, you can take a taxi to Gustavus and fly out. With a hard-shelled boat, you must take the Alaska State Ferry to Juneau in order to connect with the rest of the Alaska Marine Highway ferry system for connections south or north. This new route opened in 2011.

Icy Strait: Juneau (mile 0/1,150) to Bartlett Cove (mile 77/1,227)

Icy Strait: Juneau (mile 0/1,150) to Bartlett Cove (mile 77/1,227)

Whichever way you arrive in Juneau, you must now prepare to launch from your previous point of completion—Douglas Harbor, the Harris/Aurora marina complex, or Auke Bay. This route description begins where it left off, at the Harris Harbor. The launch ramp at Harris Harbor is adjacent to the south side of a blue storage building and separated from it by a strip of grass, where gear can be organized and stockpiled. It gets plenty of sun, offers some wind protection, and sees little traffic.

Pack enough provisions for this entire section—the 130 miles to Muir Glacier and the 53-mile return paddle to Bartlett Cove. Gustavus, the only town (with all services) along the route, is very spread out, is not really a waterfront community, and has no harbor other than a long access pier spanning the tidal flats that front the town. Though you could resupply there, it may be simpler not to. Bartlett Cove relies on a road connection with Gustavus, 10 miles distant, for supplies.

Mendenhall Bar: Mendenhall Bar is the upper half of Gastineau Channel. Specifically, it is the drying sand and mud flat between Juneau and Auke Bay. Plan well your departure from Juneau and traverse of the bar to avoid lining and dragging your boat unnecessarily. Set out from Juneau on a flooding tide, an hour or so after low tide. The center of the bar dries at a 10-foot tide or lower; any tide above 10 feet will float a kayak. Be aware, however, that actual high tide levels are frequently lower than the predicted levels. If you run out of water (provided that you launched on a rising tide), just wait for the tide to raise your boat. If you must line or drag, the footing is usually good and clean.

The Mendenhall Bar deep-water channel is well marked. You can pick up a diagram of the channel at the harbormaster’s office in the marina complex. Nine red buoys—on the right-hand side going north—and 14 green buoys on the left demarcate the navigation channel. There is little traffic up or down the bar, and currents are not difficult to deal with, as the total volume of water is not great.

Egan Drive and Glacier Highway parallel Gastineau Channel, but the sedimentary flats are so broad that the kayaker is left in comparative isolation. The Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Refuge encompasses much of the saltwater marsh area along the channel. Juneau proper soon gives way to the suburb of Lemon Creek. Due north lies the Mendenhall Glacier, Juneau’s ice tiara. The glacier is a small salient of the vast 1,500-square-mile Coast Range ice field and drains a good portion of it via the Mendenhall River. The Mendenhall Glacier has retreated only 2.5 miles in the last 230 years. The community of Mendenhall sits on its east bank. Broad alluvial fans at the mouth of the river constrict Gastineau Channel and create Mendenhall Bar, the only flat area large enough to accommodate Juneau’s airport. The channel then opens up into Fritz Cove, with Auke Bay to its north.

gastineau channel

Slip north between the Mendenhall Peninsula and Spuhn Island to enter Auke Bay. Spuhn Island is private. An old homestead—now in ruins—lies inland. An orchard and several buildings, with a Ford Model T pickup in the barn, evoke the fox farm era. Inside Auke Bay are the Juneau Alaska State Ferry terminal and the Auke Bay Public Float Facility. All services are available.

Guarding the entrance to Auke Bay lies Coghlan Island (mile 11/1,161), an on-and-off party spot for young Juneauites. Nonetheless, there are two lovely sand beaches on the west side of the northern tip that provide nice campsites.

Head for Point Louisa (mile 13/1,163), where the Auk Village Campground offers minimally developed camping for a fee at the south end of Fairhaven. The campground can be a bit confusing. It is not manned, and the area on the peninsula itself, though very suitable for camping, is not developed. Rudimentary sites inside the forest and a bit of a distance from the point itself (on its east side), require some searching. The well-developed, very visible sites with ramadas and BBQs (also east of the point) are technically picnic sites. For centuries, Auk Village was the site of an Auk Tlingit winter village. The Yax-te totem pole commemorates the site.

If heading for Skagway instead of Glacier Bay, Point Louisa is the departure point for Alternate Route #1, now described. The continuation of the main route will follow the description of the alternate.

Alternate Route #1: Lynn Canal/Point Louisa (mile 13/1,163) to Skagway (mile 95/1,245)

Alternate Route #1: Lynn Canal/Point Louisa (mile 13/1,163) to Skagway (mile 95/1,245)

From Point Louisa, turn north up the coast into Favorite Channel. The highway out of Juneau continues to mostly follow the coast all the way to Berners Bay. Pass Lena Cove, Tee Harbor, the National Shrine of St. Thérèse, Pearl Harbor, and Dotsons Landing (Amalga Harbor). At Eagle River (mile 24/1,174) things are not what they seem. For one, the shoals formed by the river’s delta indicated on most maps have coalesced into permanent real estate with a young forest and a white sandy beach that makes for great camping. Additionally, the Forest Service campground indicated on most maps as being at the mouth of the river is actually just a bit up-river and impractical for sea kayakers to use unless tides cooperate.

About 2 miles north of Eagle River sits Sentinel Island (mile 26/1,176). The now-unmanned lighthouse is available for rent—maybe—at $75/day/person from Sentinel Island Lighthouse, P.O. Box 2126, Juneau, AK 99802 (907-586-5338). Adjacent Benjamin Island (mile 27/1,177) has a beautiful tombolo camp at its south tip, while the cove on the northeast coast also has a campsite. Just off Benjamin’s north tip sits North Island, home to a sea lion rookery. Favorite Channel between Shelter Island and Benjamin Island is a preferred feeding ground for humpback whales. It is not unusual to see them bubble-net feeding here.

Once past Benjamin Island you enter Lynn Canal proper. About a mile north of North Island, just before two small islands in a cove, there are a couple of campsites (mile 31/1,181) in the forest between the shore and the road. Bridget Cove (mile 33/1,183) is protected by Point Bridget State Park and known locally as Camper’s Cove. Yes, there is camping there. Camping is also possible right on Point Bridget (37/1,187), which boasts an Alaska State Park cabin, and in the two coves just inside Berners Bay. The state park marks the end of the road extension from Juneau.

Cross the mouth of Berners Bay. Up the coast, by the Bern triangulation mark (mile 44/1,194), there are both a cleared area and a small but inviting deciduous grove that make for good campsites. There’s another campsite another mile up the coast in a small cove (mile 45/1,195) with a stream not shown on the map. Point Sherman (mile 51/1,201) is a low, cobbled beach high enough to avoid all but the very highest tides, and so offers camping possibilities. Although the shore continues low and cobbled, avoid camping near Comet. There is an active mining operation here with heavy machinery and peripatetic helicopter support. A couple of miles after Comet the Kakuhan Range crowds the eastern shore. There are some marginal campsites just before and at the stream opposite the south tip of Kataguni Island.

Continuing up the east coast of Chilkoot Inlet is not recommended. For one, campsites are scarce, with perhaps only three possible cobble beach camps between Yeldagalga Creek and the Katzehin River (mile 76/1,226). The Katzehin’s delta, which is a great campsite, attracts wolves, bears, moose, sea lions—their rookery is just 2 miles away—and seals; but, unfortunately, constricts tidal waters in Chilkoot Inlet to such an extent that currents run swift at the constriction, making a crossing at the delta over to the Chilkat Peninsula tide dependent. North of the Katzehin, along Chilkoot and Taiya Inlet’s east shore, there are no campsites.

Conditions permitting, cross over to Eldred Rock Light, southernmost outcrop of the Chilkat Islands. Denis Dwyer reports a small cove (59/1,209), open to the north, with a rounded pebble beach that makes for a good campsite just southeast of Eldred, about where one would begin the crossing. The picturesque octagonal structure is the oldest surviving lighthouse of its kind in Alaska. Built in 1905, it has a full complement of outbuildings on the tiny rock. Kataguni Island (mile 62/1,212), the next stepping-stone in the chain, has a campsite on a giant tombolo at its southern end. Kataguni once had a fox farm. Shikosi Island Bight (mile 64/1,212), on the northeast quadrant of Shikosi Island, has a protected campsite with outlying seal haul-out rocks.

Make your way up the remaining Chilkat Islands to Seduction Point at the tip of the Chilkat Peninsula. Seductive it is. With the peninsula angled northwest by southeast for most crossings over (thereby providing some south wind protection), and with Haines nearby, the paddler can be seduced into a sense of complacency. Beware: this is the only locale in Lynn Canal where currents can be a concern. Strong outgoing tides press against the lower eastern shore of the peninsula and can be tricky to surmount. Drawn by the swirling currents and spawning populations of herring and eulachon, humpback whales congregate—especially in May and June—off Seduction Point.

Less than 1 mile up from Seduction Point, on the west side of the Chilkat Peninsula, lies Dalasuga Island (mile 68/1,218—and 1 mile off-route). Dalasuga, known to locals as High Water Island, is connected to the mainland by a pebble tombolo except during extreme high tides. There’s a good campsite with fresh water (unless it’s been a particularly dry summer) just north of the cove, near a private cabin. Matt Hawthorne, in the June 2012 issue of Sea Kayaker, reports that it’s a good Dolly Varden and cutthroat trout fishing spot.

About halfway up to Flat Bay, southernmost extension of the North American road grid down Alaska’s Panhandle, at mile 70/1,220, there’s a fine campsite. Finally, about 5 miles before Haines, an enchanting little peninsula (mile 78/1,228) with beautiful campsites on both sides protrudes into the channel.

Haines: Haines frills the edges of Portage Cove. Approaching from the south, Port Chilkoot (now incorporated into Haines and harboring the cruise ship and Alaska State Ferry terminal) is the first bit encountered. Just west and behind the second mega-dock is a sandy beach used by the locals for wading and sunbathing—a good landing spot, especially if you plan on just a bit of sight-seeing. Alternatively, you can dock farther on, in Haines proper, at the small boat harbor where tidal fluctuations are not a concern. The Oceanside Campground, with showers, laundry facilities, and even sheltered tent sites lies adjacent.

The prosaically named Haines (population 2,000) is, in some respects, just a suburb of Klukwan. When John Muir and his Presbyterian missionary sidekick, S. Hall Young—led by their Tlingit guides all the way from Wrangell—paddled their canoes into Klukwan, Young was seeking a site for a mission. The Chilkats kindly granted the property in Portage Cove. By 1881 the mission was fully established and named after one of Young’s patrons, Mrs. F. E. Haines, secretary of the Presbyterian home mission board that had raised funds for the outpost. The following year, salmon canneries moved in. Haines Packing Company, the longest survivor, closed in 1972 (though there is still a small halibut and salmon fish-smoking operation in Port Chilkoot).

Haines was well prepared for the Klondike gold rush. The Chilkat Trail over Chilkat Pass into the Yukon, though a bit longer, was not as steep or rugged as the Chilkoot or White Pass Trails. By 1897, Jack Dalton, a shrewd operator and seat-of-the-pants businessman, had acquired “rights” to its use from the Chilkat natives, improved the roughest parts, renamed it the Dalton Trail, and charged prospectors a toll.

In 1903 the government built Fort William H. Seward, later renamed Chilkoot Barracks, at the site of Port Chilkoot. The fort was decommissioned and sold in 1946 when a spur of the Al-Can highway reached Haines. In 1972, the fort became a national historic site and its name was changed back to Fort William H. Seward. Today the fort is an anarchic mix of abandoned buildings, arts and crafts workshops, B&Bs, small enterprises, and private residences.

Haines remains the principal link between the blacktop highway and the Alaska Marine Highway. Tourism, fishing, a small lumber mill, a resurgent Tlingit presence, the world’s largest gathering of bald eagles (about 3,500), and a striking location keep the town going.

Bald Eagles

No, they’re not called “bald” eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) because they resemble a cue ball. The name comes from the Welsh word balde, meaning “white.” In Southeast there is one eagle nest for every 1.25 miles of shoreline, with Admiralty Island having the greatest density of nesting birds.

Eagles are classed as raptors, preferring fresh fish, but they’ll feed on small mammals, shellfish, and carrion. They take about five years to mature, and females end up larger than males. Eagles often return to established nests for brooding year after year, adding twigs each time. One 34-year-old nest has tipped the scales at over 2 tons. In Alaska it is illegal to kill or possess an eagle, dead or alive, or to possess any part of an eagle, including feathers.

The 14-mile run to Skagway is best ventured early in the morning. The funneling effects of Lynn Canal’s upper reaches can magnify the barest breeze and create dangerous, shearing chop. Coupled with the fjord’s sheer sides, it can turn into a kayaker’s worst nightmare. Either spend the night in Haines or at the tip of Taiyasanka Harbor’s fronting spit (mile 84/1,234)—Ferebee Glacier’s old terminal moraine (but beware: the spit attracts brown bears). If Lutak Inlet’s mouth is too windy or choppy, you can carve a make-do campsite around Tanani Point.

There are few landing spots in Taiya Inlet. Cross over to the east shore before the winds build up, preferably at a somewhat narrow spot and during a favorable tide.

Skagway: Logistically, Skagway is a kayaker’s dream. Paddle into the small boat harbor at the very end of Taiya Inlet behind the breakwater and check in with the harbormaster. The marina is flanked on the right by the cruise ship docks and on the left by the Alaska Marine Highway ferry terminal. The facilities include kayak racks and showers. Immediately behind the harbor is the Pullen Creek RV Park with grassy tent sites under mature trees. Behind Pullen Creek is the White Pass & Yukon Route Railway depot. The airport is three blocks away. Skagway is connected to the Al-Can by the Klondike Highway.

Captain J. B. Moore was well set up to strike it rich in Skagway prior to the Klondike gold rush. On October 21, 1887, he filed for a 160-acre homestead at the present town site. When gold was discovered in the Yukon 10 years later, Skagway became the primary gateway to the Klondike goldfields. That year, 1898, the town swelled to 10,000 with another 20,000 to 30,000 heading into the Yukon over Chilkoot Pass, White Pass, and distant Chilkat Pass. But the trek was so arduous that White Pass was soon dubbed “Dead Horse Trail” after all the rotting carcasses.

Sensing a different sort of gold mine, a consortium of local entrepreneurs and English financiers led by Irish railroad contractor Michael J. Heney broke ground for a Skagway-to-Whitehorse railroad over White Pass in May of 1898. Twenty-six months later, in July 1900, the 110-mile railroad was complete. The accomplishment remains one of the world’s greatest engineering feats. Heney is quoted as having declared that with “enough dynamite and snoose” he could build a railway to hell. That year, Skagway became the first town in Alaska to incorporate, but by then the boom was over and the population declined to 3,000. Still, the town and railroad prospered as vital links in an integrated ship-train-truck system that was the primary supply line to the Yukon.

During World War II, Skagway again swelled as thousands of men, machinery, and materiel sailed into town and rode the rails over White Pass to build the Al-Can highway. In spite of its narrow gauge and short remit, the WP&YR was a world-class innovator leading the way in developing and implementing the modern integrated containerized shipping industry in the 1950s and ‘60s. In 1978 the South Klondike Highway connecting Skagway to the Al-Can was completed. The new road, along with the closure of nearby mines that had used the railroad for ore transport, closed the now-uneconomical rail line in 1982.

But the summer tourist boom—in 2017 over 1,300,000 strong—continues to grow. In 1989 the railroad reopened on an excursion basis to cater to a new generation of nostalgia prospectors. Skagway’s population reflects the new realities; the population, only about 900, dwindles to a few score during the winter.

There’s quite a bit to see and do in Skagway. Though much of the town has been rebuilt, it is not a Potemkin village. The hotels and saloons are still the very same that catered to the stampeders; the boardwalk sidewalks are inconspicuous in their appropriateness. And the WP&YR is lovingly and authentically restored—a true living museum instead of a tourist trap. Don’t miss the ride up to the Canadian border, offered two to three times a day every day during the summer.

For the more adventurous—and for those with more time—the hike up Chilkoot Pass, along the now-preserved Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, recapitulates the climax of what the Inside Passage was originally all about. The trek is so popular that reservations are required. Any number of local outfitters can help with the logistics for whatever intensity your hike requires, including the return (that is, if you don’t plan on paddling on down the Yukon River). Visit the National Park Service office right next to the WP&YR depot to inquire and make arrangements, and take a look at Jennifer Voss’s Klondike Trail: The Complete Hiking and Paddling Guide, 2001.

Main Route: Continued . . .

Main Route: Continued . . .

From Point Louisa, the main route crosses the junction of Lynn Canal with Stephens Passage and Chatham Strait by island-hopping to Shelter Island and Admiralty Island’s Mansfield Peninsula. Lynn Canal joins Stephens Passage via Favorite and Saginaw channels. Currents at the south end of Lynn Canal average 0.3 to 1 knot. A 2-mile crossing of Favorite Channel separates Fairhaven from Adams Anchorage at the south end of Shelter Island. Another 2-mile crossing, this time of Saginaw Channel, attains tiny Barlow Point on Admiralty Island. Currents at this transect can be tricky. Ebb currents, flowing north, are about twice as strong as floods and can attain 2 knots. When the moon is in quadrature (90° to the sun), the current frequently ebbs throughout the day. Slip between Barlow Point and the Barlow Islands into Barlow Cove, a popular, local small-craft anchorage.

The northern tip of Admiralty Island is capped by beautiful Point Retreat Light. Landing is not particularly easy. Turn south along the Mansfield Peninsula until a suitable opportunity for crossing Lynn Canal over to the Chilkat Peninsula presents itself. Between Point Retreat and Funter Bay a 10- to 20-foot-high granite shelf lines the coast. Some sections are wide enough for a clean, scenic, and commanding camp, particularly near mile 27/1,177—shelf camping (see photo on page 48) is your best bet. Though the crossing of Lynn Canal is only 3 miles wide, and currents rarely exceed 1 knot, a camp along this ledge is ideal for an early morning crossing to Point Howard. Alternatively, Funter Bay—as much as 5 miles off-route, depending from where exactly you choose to cross—has extensive beaches at the head of Coot Cove. The bay has two state-maintained public floats, some cabins at the head of Crab Cove, and the ruins of the Funter Bay Cannery.

Couverden Island Group: South of Point Howard, a scallop indents the mainland shore, giving entry to a delightful group of islands with protected waters. Many of the islands in the Couverden Group (mile 37/1,187) are campable. Stephen Hilson reports an abandoned Tlingit village and an abandoned cannery in the bight just due north of Ansley Island. At high water, a marked passage connects Lynn Canal with Icy Strait along the mainland shore. At most other times, passage is possible just north of the northwest tip of Couverden Island. A public float in Swanson Harbor faces Ansley Island. At low water, this transit requires a short portage. There is a good campsite on the Couverden Island side. In the late 1800s, Couverden Island was the site of an Anglo village and a wood depot for early steamboats.

couverden islands

Round the southern tip of the Chilkat Range peninsula and enter Icy Strait. Two miles up the coast, where the 1:250,000 Juneau quadrangle indicates a cabin, Hilson locates historic Grouse Fort, an abandoned native village. The coast turns north into Excursion Inlet, and the Chilkat Range looms precipitously right out of the water. This section is known as the “home shore” and traditionally is reported to be a good fishing area.

Excursion Inlet: About 3.5 miles inside Excursion Inlet lies the small settlement of the same name, consisting mostly of a cannery with support services. During WWII the settlement was the site of a major military base built to supply Aleutian operations. It could accommodate 5,000 men and five liberty ships. Unfortunately, it became obsolete before completion. So the base was converted to a POW camp, and 1,200 captured German soldiers were shipped in to dismantle it. Escapes were discouraged by a presentation that included a detailed map of the area that indicated they were a long way from nowhere in the middle of a wilderness and that they were surrounded by ferocious bears and Indians who had never been conquered by white men. Only two prisoners escaped. They soon returned voluntarily, having been eaten by mosquitoes, treed by a bear, and scared by Indian fishing boats in the area.

Before heading into Excursion Inlet, cross westward to the Porpoise Islands, site of Steve Kane’s 1923 fox farm, and on to Pleasant Island.

Pleasant Island: Noon Point (mile 57/1,207), Pleasant Island’s eastern point, is a particularly attractive campsite: a scattering of white sandy foyers nestled among rocky outcrops. Most of Pleasant Island’s north shore also offers good camping. On October 24, 1879, John Muir, his companion (Presbyterian missionary S. Hall Young), and their Indian guides camped on the western shore of Pleasant Island en route to Glacier Bay. After stocking up on firewood in anticipation of camping on ice, Young christened the place Pleasant Island because “. . . it gave us such an impression of welcome and comfort.”

Enter Icy Passage. Normally one would be tempted to almost bypass Pleasant Island and course along the mainland’s south coast. In this case, however, the island’s camping and welcoming shores offer an attractive route, while extensive—sometimes mile-wide—drying sandy flats befoul Icy Passage’s north shore. Somewhere past Pleasant Island’s northernmost tip, angle across Icy Passage to the Gustavus pier.

Gustavus: Gustavus (population 260) is the town that serves Glacier Bay National Park. The town was founded in the early 1920s by the Matson family as a homestead with the encouragement of federal agencies to help develop the area. Located along the mouth of the Salmon River, the village is an atypical Inside Passage settlement in that it is spread out over flat and fertile deltaic terrain with difficult shoreline access. (It is more than a mile from the head of the pier to Gustavus.) The Matsons developed a farming community that provided meat, garden produce, and especially strawberries to a growing regional economy. All services are available. From a kayak, sampling Gustavus’ riches is not easy and probably best left to a post-Inside Passage completion visit by road from Bartlett Cove. A handful of historic lodges, inns, and B&Bs dot the community and would make a delightful penultimate celebratory stay before embarking back to Juneau.

Continue on to Point Gustavus (mile 72/1,222), staying as far from shore as tidal conditions warrant. At the point, currents—which can attain 6 knots entering and exiting Glacier Bay all the way up to Willoughby Island—minimize sand deposition, and the shore offers attractive camping possibilities without long carries. Lemesurier Island, southwest of Point Gustavus, is home to the largest and most successful concentration of the reintroduced population of sea otters along the Inside Passage. A 1995 estimate put the entire sea otter population of Alaska at more than 150,000, but the historical fluctuations have been enormous. The fur trade wiped out the Southeast sea otters by the early twentieth century. Today’s Southeast sea otters are descended from about 400 animals reintroduced to the region from the Aleutians in the 1960s. They are now ranging as far north as the Marble Islands inside Glacier Bay. In 2002, Southeast sea otters numbered 11,000 and by 2011 had increased to 26,000, while hunting has also increased. Alaska Fish and Wildlife biologists are working to determine a sustainable harvest limit.

Turn north into Glacier Bay National Park and paddle another 5 miles to Bartlett Cove (mile 77/1,227), the park’s headquarters. Head for the boat launch between the breakwater and fuel dock and the large National Park Service public-use dock. The park’s visitor information kiosk is located at the foot of the pier. A variety of accommodations, from free camping to luxury lodge suites, are available.

Glacier Bay: Bartlett Cove (mile 77/1,227) to Muir Glacier (mile 130/1,280)

Glacier Bay: Bartlett Cove (mile 77/1,227) to Muir Glacier (mile 130/1,280)

Glacier Bay National Park: Much to the consternation of the Matson family and several of the local native residents, President Calvin Coolidge created Glacier Bay National Monument in 1925, limiting commercial activity and preserving about half the present park area. The monument was increased in size in 1939 and made a national park in 1980, at which time it was enlarged again to its present size of 3.3 million acres with the addition of the Alsek River estuary. In 1986 UNESCO designated the park a Biosphere Reserve, and in 1992 it became a World Heritage Site.

Bartlett Cove has limited services. White gas and bear canisters are available. Gustavus, 10 miles distant, has groceries and a hardware store, but transportation between the town and the cove is expensive and often slow. The national park campground is just west of the landing pier. It is well protected, well developed—including free firewood, rain shelters, and warming stoves—and is absolutely free, though you must register at the park check-in kiosk. Laundromat and showers are available. Glacier Bay Lodge has rooms for about $200 (2017). The lodge restaurant is excellent, with reasonably priced breakfasts and lunches. Dinner can be expensive.

Kayaking is very popular in the park. If it gets too popular, the Park Service may consider implementing a quota system similar to the one in place for motorized vessels. Before undertaking a paddling trip, you must register and attend a video orientation. There is a kayak transport concessionaire that offers drop-off and pickup service. Drop-offs must be arranged in advance. Though pickups are also best arranged in advance, the concessionaire’s boat will not pass you up if you’re at one of the designated pickup spots at the proper time and can pay the shuttle fee. You are now ready to complete the last portion of the Inside Passage.

Beardslee Islands: Though most traffic enters Glacier Bay through Sitakaday Narrows, this constriction causes a Venturi effect that can accelerate currents to 7.5 knots and create tide rips that are best avoided in a kayak. For the paddler, the best route into Glacier Bay is through the Beardslee Islands. These islands are low-lying—the tallest is only 200 feet high—protected, ringed by shallow waters, dense with greenery, full of wildlife, and closed to motorized travel from May 15 to September 15. They are a maze to navigate. With the Beardslees isostatically rising 1.8 to 2 inches a year, interisland channels disappear and new islands appear with surprising rapidity. Chart makers can barely keep up. Additionally, with so many tiny landforms and few unambiguous landmarks, chart scale—the chart’s ability to display minimal features—must be taken into account. In the Beardslees, your map may actually be wrong—in spite of a lousy map-reader’s first instinct, namely to question the map instead of his skill. Get the highest resolution and most up-to-date chart available and don’t lose track of your location. There is no fresh water in the Beardslees.

There are three routes into the archipelago. The most popular with kayakers, and easternmost of the three options, is round the eastern end of Lester Island. This passage dries at low tide and is passable only near high tide. Depart Bartlett Cove one to two hours before high tide. Leaving after high water exposes the paddler to contrary currents, often strong enough to impede relaxed progress.

Alternatively, exit Bartlett Cove around Lester Island’s west end and slip into Secret Bay through the channel between Young and Lester islands, thereby avoiding the strong currents—up to 6 knots—that dominate Glacier Bay’s main channel. This smaller channel also dries at low tide, but its window of opportunity is broader. Exit Secret Bay through the channel that separates the northern tip of Young Island from the newly attached northern peninsula of Lester Island. The western shore of this peninsula (mile 81/1,231) has a good campsite.