The largely Christian Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–38 was the only serious challenge to be mounted against the rule of the Tokugawa in two and a half centuries. In this detail from the Shimabara Screen we note that inscriptions have been written on the inside of the walls. They are probably prayers to encourage the defenders. Above the planking wall is a wooden framework from which bamboo curtains have been suspended to hide the defenders from outside gaze. Women and children of the community are preparing a meal for the defenders.

Within two years of Hideyoshi’s death, Christianity in Japan, already changed in spirit by the martyrdoms of Nagasaki, also changed somewhat in form by the replication in Japan of the profound division within Christendom that had scarred 16th-century Europe. The Jesuits, who already had problems explaining their faith to increasingly hostile rulers, now also had to explain why the Christianity that they had left behind in Europe was far from being a seamless robe. For the first time in Japan they had to face up to the fact that there was something called Protestantism.

Unlike the Catholic missionaries who followed the Portuguese merchants, the first Protestant visitors to Japan were not succeeded by Lutheran or Calvinist pastors. The sole concern of the Dutch and English was trade. Conversion of Japanese people was of no interest to them; the only religious element in their make-up was a strong antagonism to Catholicism. The Dutch had been fighting a war of independence from Catholic Spain for many years, and the first Englishman to visit Japan, the famous William Adams, had been the captain of a ship that fought the Spanish Armada.1 Apart from this knee-jerk reaction, which their Japanese hosts picked up on very quickly, their attitude towards religious matters in general was one of non-interest, and towards Japanese religion – whatever that was – one of utter and complete ignorance shrouded in a cloak of 17th-century prejudice. On 30 January 1622 Richard Cocks of the East India Company wrote the following in his diary:

And so we went to the Hollanders to dinner, and they came to us for supper, we having in the afternoon visited the pagoda of Ottongo Fachemon [Hachiman], the god of war, which out of doubt is the devil, for the picture showeth it, made in form as they paint the devil, and mounted upon a wild boar without bridle or saddle, and hath wings on his shoulders, as Mercury is painted to have.2

In other words, this ‘Hachiman’ must be the devil because his picture matched the description Cocks had learned from his childhood. Though the revelation did not excite within Cocks’ breast any desire to burn down the shrine, the Jesuits’ own converts could not have provided a better example of naïve condemnation.

The first Dutch ship to visit Japan was the sole survivor of a fleet of five vessels that left Rotterdam on 27 June 1598. Arriving off Bungo province on 9 April 1600, the lucky ship was the Liefde, which became the first vessel of any nation to reach Japan from Europe via the Straits of Magellan.3 To complete a trio of ‘firsts’, also on board the Liefde was William Adams (mentioned above), the first Englishman to set foot in Japan.4 The threat that their arrival posed to the existing Iberian trading hegemony became immediately apparent when the Portuguese insisted to anyone who would listen that the ‘land of the gods’ had just taken delivery of ‘a party of piratical heretics’. This unflattering complaint was made forcibly to Tokugawa Ieyasu, who is referred to by Adams as ‘the great king of the land’ – a prescient statement, for this was effectively what Ieyasu was shortly to become.5 As well as apprehending the crew, Ieyasu confiscated the armament of the Liefde, some of which may have been used at his decisive victory at the battle of Sekigahara on 21 October 1600.6

Tokugawa Ieyasu was one of history’s great survivors. Taken as a hostage when a child, and made to fight for one of Japan’s least successful daimyõ when a young man, he gradually asserted his independence and allied himself in turn with Nobunaga and Hideyoshi. As an adherent of the Jōdo sect, much of his early military experience consisted of defending his domain against the Ikkō-ikki. He eventually settled in eastern Japan on land presented to him by a grateful Hideyoshi. Its distance from Ky sh

sh allowed him to avoid service in Korea, which ensured that his troops were in better shape than those of many of his rivals who had suffered in that conflict. The battle of Sekigahara made Ieyasu ruler of Japan, and three years later he revived the post and title of Shogun. He made his own castle town into Japan’s administrative capital. Known as Edo, it proved to be a highly successful choice, as may be judged from the fact that Edo is now known as Tokyo.

allowed him to avoid service in Korea, which ensured that his troops were in better shape than those of many of his rivals who had suffered in that conflict. The battle of Sekigahara made Ieyasu ruler of Japan, and three years later he revived the post and title of Shogun. He made his own castle town into Japan’s administrative capital. Known as Edo, it proved to be a highly successful choice, as may be judged from the fact that Edo is now known as Tokyo.

Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first Tokugawa Shogun, shown here in a shrine to him in Okazaki.

The year that saw the initial triumph of the first Tokugawa Shogun also marked the beginning of a partnership between Japan and her new arrivals from the Netherlands. On the last day of the momentous year of 1600, Queen Elizabeth I put her signature on the Royal Charter that gave birth to the ‘Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies’ – commonly known as the East India Company (EIC).7 English trade with Japan was first mooted in 1608, when John Saris, an official in the EIC’s factory in Bantam in Java, submitted a report to the Company’s directors in which he suggested that, in contrast to the tropical East Indies, colder Japan would provide a market for English woollen broadcloth.8 Further impetus was provided by the news of the establishment of a Dutch factory (trading post) in Hirado in 1609,9 where, according to William Adams in a letter of 23 October 1611, ‘the Hollanders have here an Indies of money’.10 Thus convinced, the EIC directors agreed that relations with Japan should be pursued.

The first EIC vessel to sail to Japan was the Clove. It reached Japan, with the enthusiastic John Saris on board, on 11 June 1613. The ship docked at Hirado where the Dutch were already established. The Dutch provided no opposition, and the Englishmen were warmly welcomed by the local daimyõ, Matsuura Shigenobu, whose prayers to Hachiman before the Korean campaign had seen him return home safely and prosper since then. The party headed east to meet Tokugawa Ieyasu at Shizuoka. Ieyasu had by then retired from the post of Shogun, so this audience was followed by a visit to Ieyasu’s son, the new Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada (1579–1632), in Edo. When John Saris sailed from Japan on 5 December 1613 he left behind a factory on Hirado staffed by five Englishmen. Richard Cocks was appointed as its director, while Saris spent many long months travelling between England and Japan. Writing to the EIC in October 1614, he suggested those items that might be most advantageously sold to Japan, including ‘pictures, painted, some lascivious, others of stories of wars by sea and land, the larger the better’.11

Over the next two decades the diaries, reports and correspondence of the EIC painted a vivid picture of political developments in Japan and the relationship between the samurai and the traders’ perception of the sacred. On 20 June 1618 Richard Cocks wrote about how he had come face to face with a rather unpleasant warrior, an account that shows he had a complete understanding of the samurai’s position in society:

A mad gentleman (it is said) having been possessed with the devil more than a year past, was at this day at a banquet with his father, brother, wife and kindred, they persuading him to be better advised and leave off such courses. But on a sudden, before it could be prevented, he started up and drew out a cattan [the katana – the Japanese samurai sword] and cut off his brothers head, wounded his father, almost cutting off his arm, and cut his wife behind her shoulder on her back, that her entrails appeared, wounded diverse others, and slew out right his steward (or chief man). And yet it is thought nothing will be said to him, they which he hath killed being his kindred and servants, he being a gentleman.12

Cocks’ main dealings with the samurai class were mediated through the Matsuura family who ruled the territory where the English factory was located and had to be kept sweet. This did not always work out, as on 10 August 1617, when ‘the king’s brother sent back the parrot I gave him, to keep her, she being sick, or I rather think to have a better present sent in place, for the parrot is well’.13 Cocks was always intrigued by Japanese religion, even if he did not understand it. In 1614 he went to see a newly built pagoda erected in memory of two men who had killed themselves to accompany the late emperor in death.14 By comparison, Catholicism was something he both understood and despised, particularly in the means by which it was disseminated among the Japanese, as this diary entry suggests:

November 30 1617. I received a letter from Mr. Wickham to report popish miracles, how a man’s arm was dried up for offering to burn a friar’s cope or vestment, his arm standing stiff out, he not being able to pull it back nor bend it. Thus do these Popish priests invent lies to deceive the poor simple people.15

As for politics, several letters describe how in 1614 Toyotomi Hideyori, the surviving son of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, rebelled against Tokugawa rule. Regarding Ieyasu as a usurper, Hideyori packed Osaka castle with thousands of rõnin (masterless samurai) who had been dispossessed since Sekigahara,16 many of whom were Christians. English and Dutch cannon, which were monsters compared with the Japanese varieties, played a vital role in crushing them. For the next couple of years Dutch and English trade flourished, but a decline began following the death of Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1616. Hidetada was far less sympathetic towards European contacts than his father had been, and decreed that trade was to be confined to Hirado and Nagasaki. His decision may have been due to pressure from Japanese merchants, but it also involved the underlying fears of Christian subversion and foreign intervention which the Osaka operation had highlighted once again.

In spite of these fears Christian martyrdom and persecution during the first few years of the Tokugawa Shogunate were sporadic throughout Japan, and were interspersed by periods of calm during which the Church more than held its own. The major shift in policy came with Ieyasu’s edict of 1614 expelling all foreign priests and closing all churches. This resembled Hideyoshi’s edict of 1587 in that it was not enacted immediately with any great severity, and no foreign priest perished during Ieyasu’s lifetime. Boxer nevertheless describes the missionaries clearing all pictures and religious objects from their churches before the hand-over, and even going to the lengths of re-burying the bodies of their colleagues in secret locations so that their graves would not be profaned. Many priests, however, did not leave Japan, instead staying behind to minister in secret. This was the beginning of the ‘underground church’ of the senpuku Kirishitan (secret Christians). Boxer numbers these brave men at 47, plus a hundred dõjuku (Japanese lay catechists), and they were to be joined later by priests smuggled into Japan.17

One way by which the secret Christians concealed their faith was by worshipping statues of the Virgin Mary disguised as Kannon, the Goddess of Mercy. This particular Maria Kannon is in Hondō on the Amakusa islands.

The discovery that foreign priests were present in Osaka castle led Hidetada to strengthen his father’s edict by another in 1616, although the accent was still on the expulsion of foreign clergy rather than the persecution of native Japanese Christians.18 As the Japanese authorities had not quite grasped the difference between Protestant and Catholic, the English and Dutch traders were repeatedly questioned about their religious adherence. Cocks writes in 1617 that Hidetada’s advisers ‘sent unto me I think above twenty times to know whether the English nation were Christians or no’. Cocks had first answered simply in the affirmative, but in response to further questions he had hastily added that ‘all Jesuits and friars were banished out of England before I was born’. This seems to have satisfied the authorities, and with the warning that if the English should communicate with the Portuguese ‘they should hold us to be all of one sect’, the English trading privileges were restored.19 In fact, the Protestant sensibilities of both the Dutch and the English had long ensured that they were completely unsympathetic to Catholic Europe. Anti-Christian daimyõ such as Matsuura Shigenobu behaved more charitably towards fugitive Catholic priests than did the avowedly anti-Papist Richard Cocks, who turned over to the Japanese authorities a priest in hiding whose whereabouts became known to him.20 Cocks’ attitude is summed up by a passage in a letter he wrote on 17 February 1614: ‘Here is reports that all the Papist Jesuits, friars and priests shall be banished out of Japan… but I doubt the news is too good to be true.’21

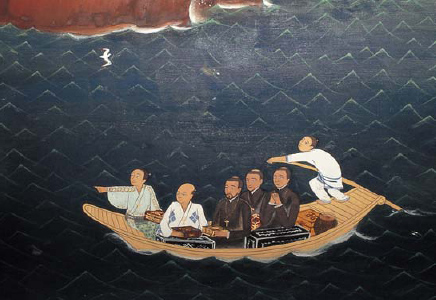

Three priests are rowed ashore in secret to minister to the Japanese Christians.

The underground priests had only a few years left to suffer the attentions of unsympathetic Englishmen, as rivalry between the Dutch and the English themselves, rather than Catholic against Protestant, eventually sealed the fate of the EIC’s venture in Japan. Following the Anglo-Dutch peace agreement of 1619 there was some cooperation, manifested largely through joint attacks upon Spanish and Portuguese ships trading with the Philippines, a process that turned out to be more profitable than honest trade. From December 1621 serious consideration was given to closing the English factory in Hirado. The end came following the Amboyna massacre in 1623, when an English captain was tortured and executed on the grounds of having plotted to overthrow the Dutch garrison. As a result of this incident the EIC decided to concentrate its efforts on India, abandoning Japan.

The year 1623 also saw the accession to the Shogunate of the third Tokugawa Shogun, Iemitsu. The underground priests held their breath lest the new broom would sweep cleaner than the old. As they had feared, Tokugawa Iemitsu (1603–51) was to prove more fiercely anti-Christian than either of his predecessors, taking a curiously personal interest in the investigative procedures employed against those priests brought out into the light.22

The ‘Christian cave’ on the island of Wakamatsu in the Gotō group, where Christian believers met for secret worship.

The control that successive incumbents of the post of Tokugawa Shogun exercised against Christianity was but one aspect, albeit a very important one, of the control they endeavoured to exert over every facet of Japanese life. The ideology that lay behind the Tokugawa polity was Neo-Confucianism, which will be discussed later in ‘The Ways of the Warrior’. For now we may note that any tension that existed between the ideas of ancient Chinese sages and the demands of the Tokugawa state were overcome by the reinterpretation and transformation of Confucianism itself. It was a familiar Japanese process, and the fact that it was used to control the one religious import that had not been willing to adapt shows how extremely the threat from Christianity was perceived.23

The order and stability that Neo-Confucianism cherished received its expression in the overall administrative machinery that successive generations of the Tokugawa refined. It was known as the bakuhan system, being composed of two elements: the central bakufu or Shogunate and the local government of the han, the daimyõ’s fiefs. It is not surprising to see both these elements being brought to bear on the problem of Christianity.24 In Iemitsu’s time the control of the pernicious sect was undertaken largely at han-level through the office of the local bugyõ (magistrate), who oversaw all legal matters together with the metsuke (censors), the ‘all-seeing eyes’ of Tokugawa Japan. The particular department covering these local religious affairs was known as the Sh mon aratame yaku (Bureau for the Investigation of Religion). The local inquisitors (a good analogy if not a direct translation) would examine cases brought to their attention where people were believed to have had transgressed from the Confucian demands of kõ (filial piety) and ch

mon aratame yaku (Bureau for the Investigation of Religion). The local inquisitors (a good analogy if not a direct translation) would examine cases brought to their attention where people were believed to have had transgressed from the Confucian demands of kõ (filial piety) and ch (loyalty) by embracing a banned religion.

(loyalty) by embracing a banned religion.

Confucianism may have provided a conceptual and administrative framework for controlling Christianity, but the actual policing function was given to the tame bulldog of Buddhism. Like every other institution in Tokugawa Japan, Buddhism was made to serve the state. In fact, it became its most humble and faithful servant: a status that was to cause it enormous problems in the reaction against the Tokugawa regime that followed the Meiji Restoration, 300 years in the future. During the 17th century, however, all Japanese, as households, were affiliated to a particular Buddhist temple. Though this was of itself nothing new, the bakufu institutionalized it on a national scale, giving the Buddhist clergy (and Shintō priests, because the Tokugawa regime recognized no practical distinction between the two) a policing function over the lives of their registered adherents with the overt aim of controlling Christianity. Under this danka system, the entire population of Japan was required to register at a bodaiji (family temple) within a defined geographical and social area. From 1671 the temples’ bureaucratic duties were extended to cover the registration of births, marriages, adoptions, deaths, changes of residence and occupation.25

The anti-Christian element of the danka system became visibly apparent through the annual examination of the members of households, who were issued with a tera-ukejõ (temple certificate) that confirmed that none of them were Christians. Until the Shimabara Rebellion, the tera-ukejõ were issued only to former Kirishitan who had given up their faith, but following that upheaval, which had a markedly Christian nature, it was made universal.26 The infamous Nagasaki bugyõ Takenaka Umene, who occupied the post from 1626 to 1631, is credited with introducing a test for Christianity by requiring those under examination to show their rejection of the faith by the simple means of trampling on a Christian image. The ritual was called fumi-e (image trampling) a word also used for the Christian images set in wooden blocks with which the test was carried out. For non-Christians, stamping on the fumi-e eventually acquired the air of an annual ritual eagerly awaited as one event of the New Year celebrations, but to the senpuku Kirishitan the trial never lost its horror. Records show what the inquisitors were looking for: ‘Old wives and women when made to tread upon the image of Deus get agitated and red in the face; they cast off their headdress; their breath comes in rough gasps, sweat pours off them.’27

Lacking the presence of an iconoclastic Protestant like Richard Cocks to tell them that all they were doing anyway was indulging in Papist idolatry, the senpuku Kirishitan had to suffer this annual denial of their faith. Yet they kept it up for generations, and having trampled upon a holy image, might then return to their homes and bring out from under the floorboards a similar image of Christ or His Mother. They would then bend the knee, and with no priest to hear their confession of such a public sin and grant them absolution, they would mumble an act of contrition, the words of which had been passed on as secretly and as faithfully as the image itself. Some secret Christians almost literally went underground in the sense of having as their churches and chapels the little store room round the back of their homes, which became the centre for worship and devotion in private groups. There they would gather, with an explanation already prepared about how the meeting was actually a village celebration with no Christian connections.

Should a secret Christian be revealed by the fumi-e process or any other, such as a raid on a house, the inquisitors could choose to bring about either death or apostasy. A Christian of the samurai class or a foreign priest might well be interrogated by Buddhist priests, among whose ranks were a few apostate Christians who pursued their calling with all the fervour of the convert. For a poor farmer or fisherman an immediate apostasy was expected as the simple reaction to the fear of death or the loss of livelihood. Torture helped the process along for either category, and Unzen, on the Shimabara peninsula, became the open-air torture chamber of the Nagasaki area. Nowadays Unzen is a popular hot spring resort, and most of its volcanic boiling water sources have been piped off into expensive hotels, leaving only one deep pool among its lunar landscape that still resembles the sight that met the eyes of its Kirishitan victims, who were either flung in or had ladles of scalding water poured over their lacerated flesh.28

One way by which Christian worship was concealed was to disguise the event as a village celebration. This is still maintained by the Kakure Kirishitan. Here we see members of the Yamada community on Ikitsuki at prayer within the home of their group leader during the Hattai-sama festival in 1995.

The aim of the torture was to make the Christians recant, because the authorities were astute enough to know that the blood of the martyrs was the seed of the Church. Apostates, on the other hand, could render a religion impotent from the damage they created. Inoue Chikugo-no-kami, who became the Tokugawa regime’s ‘Grand Inquisitor’ when the Sh mon aratame yaku was centralized in 1641, was the master of this approach. Based in Edo with no volcanic waters in the vicinity, he specialized in the torture of ana tsurushi, which involved suspending the victim upside down in a suffocating, foul-smelling pit for days on end. A gash was made in the forehead so that the Christian would not lose consciousness. To this torture was added one mercy – the left hand was kept free so that a signal could be given that he or she wished to recant. So terrible was the torture of the pit that Inoue achieved one remarkable triumph by even forcing into apostasy one Portuguese Catholic priest: Father Christovão Ferreira.29 The majority of native Christians did apostatize during these two decades, either through torture or the fear of it, but many of the resulting apostasies were, of course, as false as the apparent willingness to trample on the fumi-e. In 1637, 38,000 Christians appeared from nowhere to take part in the Shimabara Rebellion, and when searches were undertaken for secret Christians in the 1640s underground communities were found in all but eight of the Japanese provinces.30

mon aratame yaku was centralized in 1641, was the master of this approach. Based in Edo with no volcanic waters in the vicinity, he specialized in the torture of ana tsurushi, which involved suspending the victim upside down in a suffocating, foul-smelling pit for days on end. A gash was made in the forehead so that the Christian would not lose consciousness. To this torture was added one mercy – the left hand was kept free so that a signal could be given that he or she wished to recant. So terrible was the torture of the pit that Inoue achieved one remarkable triumph by even forcing into apostasy one Portuguese Catholic priest: Father Christovão Ferreira.29 The majority of native Christians did apostatize during these two decades, either through torture or the fear of it, but many of the resulting apostasies were, of course, as false as the apparent willingness to trample on the fumi-e. In 1637, 38,000 Christians appeared from nowhere to take part in the Shimabara Rebellion, and when searches were undertaken for secret Christians in the 1640s underground communities were found in all but eight of the Japanese provinces.30

The opportunity to demonstrate their non-Christian credentials, or even to make a false apostasy, was a privilege denied to those Christians who suffered one of the sporadic armed raids on suspect communities carried out during the 1640s. Such enclaves tended to be remotely located, such as the island of Ikitsuki to the north-west of Hirado.31 The Ikitsuki ‘Shōhō Persecution’ of 1645 came about not from the vigilance of a nosy metsuke but from the suspicions of the chief priest of the Sh zenji, the temple at which the inhabitants of the southern part of Ikitsuki were registered. He reported to the bugyõ that six of his adherents were probably underground Christians. All were executed, and as Ikitsuki already had a long history of Christian martyrdom going back to 1609, the daimyõ in whose territory Ikitsuki lay (the second Matsuura to bear the name of Shigenobu) acted swiftly to eliminate the problem once and for all. A boat full of samurai from the island of Iki, who had no family connections with Ikitsuki, landed on the island under the command of a certain Kumazawa Sakubei. Kumazawa began the operation like a samurai general of old by praying for victory at the Shintō shrine of Hime-jinja, high on a bluff overlooking the harbour of Tachiura. He then began a systematic house-to-house search for any evidence of underground Christianity, such as printed or handwritten texts, rosaries or other devotional items, including ones disguised as Buddhist images. Anything that gave rise to the slightest suspicion led to a massacre of the inhabitants. Hundreds were killed.

zenji, the temple at which the inhabitants of the southern part of Ikitsuki were registered. He reported to the bugyõ that six of his adherents were probably underground Christians. All were executed, and as Ikitsuki already had a long history of Christian martyrdom going back to 1609, the daimyõ in whose territory Ikitsuki lay (the second Matsuura to bear the name of Shigenobu) acted swiftly to eliminate the problem once and for all. A boat full of samurai from the island of Iki, who had no family connections with Ikitsuki, landed on the island under the command of a certain Kumazawa Sakubei. Kumazawa began the operation like a samurai general of old by praying for victory at the Shintō shrine of Hime-jinja, high on a bluff overlooking the harbour of Tachiura. He then began a systematic house-to-house search for any evidence of underground Christianity, such as printed or handwritten texts, rosaries or other devotional items, including ones disguised as Buddhist images. Anything that gave rise to the slightest suspicion led to a massacre of the inhabitants. Hundreds were killed.

Dotted around Tachiura are various memorials to the victims of 1645,32 but not all the underground Christian homes could be reached easily on foot. One fisherman’s hovel, now known as Danjikusama, could only be approached by boat. When the samurai landed there the family concealed themselves in a bamboo grove, but their baby’s cries gave them away and they were put to death. Because of the way the massacre happened this place is revered by the fishermen of Tachiura, and once a year they visit Danjikusama to pray for large catches and safety at sea. But they always walk there. No fishermen in Ikitsuki will ever go to Danjikusama by sea.33

That Ikitsuki was to remain one of the most important locations of underground Christians for the next two centuries shows that the Shōhō raid was a failure, but this was not how it appeared to the brave general Kumazawa Sakubei, one of the few samurai for many years to have used his sword in anger. With that one massacre Matsuura Shigenobu II concluded that the work was done and reported to the Shogun that there were no Christians left in his territory at all.

That was the official version. We now know that they continued to pray in secret to something very secret indeed. Behind a pillar on the wall there may have been concealed a crucifix or a holy picture that only they knew was there. A potential source of embarrassment for the Matsuura appeared in 1658 when three jabutsuzõ (evil Buddhas – the splendid name for disguised Christian statues) were discovered on Ikitsuki. The daimyõ panicked, but fortunately for his pride the owner of the images trampled on a fumi-e and was released, thereby showing the joint characteristics of secrecy and denial that were to mark Ikitsuki Christianity for the next 200 years.34

It is important to note that throughout this time of persecution the underground witness in Japan was borne exclusively by members of the lower social classes. There were no underground Kirishitan samurai to defend them with their swords, nor any ‘above ground’ Kirishitan daimyõ to plead for them in high places. Some daimyõ may have shielded communities they knew to be Christian, but this would have been largely to avoid being punished themselves; actual believers at this level were the first to apostatize. The faithful Christian daimyõ like Takayama Ukon had a bad habit of choosing the wrong side in wars where the Tokugawa were involved, and were now either dead or fled.

The sole examples of overt Christians still active in Japan were the Dutch traders in Hirado and the crews of the Portuguese ships who still called in briefly. Unlike the English, the Dutch do not seem to have helped the suppression of Christianity in any way, but neither did they promote it. If any secret Christians sought refuge with Dutch merchants then their secrets are concealed from history as well. On only one occasion was this policy of non-involvement challenged, when the Tokugawa Shogun called upon the Dutch in 1638 to assist him in suppressing the Shimabara Rebellion. The request had nothing to do with religion, and merely reflected the Shogunate’s continuing lack of faith in Japanese-produced cannon, which had been demonstrated so clearly at Osaka.

The site of a fisherman’s hovel, now known as Danjikusama, marks the place of martyrdom for a Christian family on the island of Ikitsuki. A small shrine, much like a Shintō shrine, commemorates the family. The flags have been left by local fishermen as offerings.

The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637–38 was the only serious challenge to be mounted against the rule of the Tokugawa in two and a half centuries. The uprising began on the Amakusa islands and spread to the Shimabara peninsula to the south of Nagasaki. Having failed to capture the castle of Shimabara, the insurgents repaired the dilapidated castle of Hara that stood nearby, and held off the army of the Tokugawa for several months. Thirty-eight thousand people, most of whom were Christians, defended Hara under the command of a strange messianic figure called Amakusa Shirō.35 Among the tactics used by the Tokugawa to reduce the fortress was a bombardment from ships anchored below the walls. The cannon were too light to do any damage, so the head of the Dutch factory in Hirado, one Koeckebacker, was first requested, then advised and finally ordered to send Dutch ships for service there. Even though the insurgents were Catholics who had damaged Dutch trade in the area by their rebellion, Koeckebacker displayed an admirable reluctance to provide ships and artillery to destroy them. His first move was to send one of the two ships he had available off to Taiwan so that it could not be used. He arrived off Hara in the remaining De Ryp on 24 February 1638.36

The leaders of the Sakaime group of Kakure Kirishitan on Ikitsuki kneel in front of their altar at the start of the Easter celebrations.

Two Dutch sailors died during the operation. One was shot down off the top mast and crushed his fellow to death.37 Ship to shore bombardment was then replaced by a makeshift land battery. During the 15 days that the Dutch were present at Hara they threw 426 cannon shot into it, so that, according to a Japanese source, the besiegers were required to ‘build places like cellars, into which they crowded’.38 The effect was therefore quite considerable, much greater than Koeckebacker either expected or acknowledged; however, he may well have played down the significance of his efforts because he regretted being forced into such a despicable act. One reaction by the besieged was to mock the Tokugawa army for having to rely on foreign help.39 After two weeks the Dutch were thanked for their efforts and sent away prior to the final and bloody assault against the weakened castle that settled this last rebellion against the Tokugawa.

By the time of Shimabara the Shogunate may have grasped the distinction between Protestant and Catholic; but that consideration was less important in their eyes than the distinction between missionary and merchant. Portuguese ships were still trading with Japan while the rebellion raged on. All this was to change in 1639 with the Sakoku Edict. This important milestone in the relations (or lack of them) between Japan and Europe has commonly been regarded as one not of exclusion but of seclusion, whereby Japan adopted the policy of sealing itself off from the rest of the world until being ‘awakened’ by Commodore Perry’s US fleet in 1854. Recent scholarship has called into question many aspects of Sakoku, showing that Japan was by no means totally isolated, as trade was still maintained with Korea and China. The one factor that is not disputed is the concentration of a policy of exclusion on Catholic Europe and the elimination of Christian influence. In this light, the non-existence of a secluded, isolated Japan makes the persecution of Christians appear even more severe than under the ‘seclusion’ model.40

By the Sakoku Edict Japan’s Christian century came to an end. The helpful Dutch remained on Hirado, but in May 1641 they were suddenly and forcibly removed to Dejima. It was to become Japan’s only window to the West for the next two centuries. The immediate Dutch reaction was one of resignation; however, the Sakoku Edict meant that they would be the only European nation still to be trading with Japan for the next two centuries, and this gave the cloud something of a silver lining. Although the Dutch were confined to their tiny outpost with a staff of only 27, during the 1640s the profit on the annual trade with Japan was over 50 per cent, making Dejima the Dutch East India Company’s richest trading post.41 Japanese copper was one of the elements of that trade, and silver soon became another commodity. In 1639 six ships from Japan had arrived in Taiwan with 3 million florins’ worth of silver, and up to 1668 the stream of silver from Japan was an essential factor in the company’s profits.42 In 1647 a Portuguese embassy attempted unsuccessfully to re-open trade relations with Japan, explicitly stating that the regaining of access to the copper market was one of the main motives behind the move. The Portuguese had established very successful gun foundries in Macao and Goa, where Japanese copper had been used prior to the Sakoku Edict. It is interesting to note that cannon produced in Macao using Japanese copper were employed by the Duke of Wellington during the siege of Badajos in 1812.43

In 1673 England too tried unsuccessfully to re-open trade with Japan. The investigative mission brought along two brass guns and one mortar as presents for the Shogun, but the Dutch, who feared losing their monopoly, informed the Shogun that the English were in alliance with the Portuguese. This was not strictly true, but Charles II had a Portuguese queen, Catharine of Braganza, and that was enough reason for the ship to be turned away.44 It was not until the founding of Hong Kong that the EIC came into contact with the Japanese again.45

Mr Ooka, leader of one of the Kakure Kirishitan groups on Ikitsuki, kneels to pray in front of the holy pictures preserved and successively copied in secret for hundreds of years.

Meanwhile the work of the ‘Inquisition’ continued, but by the beginning of the 18th century its tasks were becoming routine. In 1708 there was a flurry of excitement when Father Sidotti, the last in a long line of secret missionaries, landed in Japan and was immediately arrested. He died in prison in 1715. Following his death the Christians’ prison was used for common criminals, then abolished altogether along with the ‘Inquisition’ itself in 1792, its work apparently completed. As far as everyone was concerned, Christianity had been totally eliminated from the ‘land of the gods’. It was a century and a half before the true situation was revealed.

The shaking of the foundations of the Tokugawa Shogunate began in 1854 with the arrival off the Japanese coast of an American fleet commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry. Not frightened away by the sight of armed samurai warriors glaring at them from the beach, the Americans landed, ending two centuries of Japan’s self-imposed isolation. Trade negotiations followed. Ports were opened up and foreigners in strange, outlandish clothes began to walk the streets of Japan for the first time in two and a half centuries.

Among the foreigners allowed back into Japan were Catholic priests – not Portuguese Jesuits this time, but French missionaries who had studied the history of Christianity in Japan and its tragic extinction. The martyrs of Nagasaki had been canonized as recently as 1862, so Japan was in the forefront of Catholic thought. Missionary work among the Japanese was still out of the question – the churches that the priests were allowed to build were for the convenience of foreigners only – so the first concern with regard to the Japanese was simply to search for the descendants of the ancient Christians, ‘whose existence they presumed’.46 Such presumption had not dared to include the discovery of communities numbered in the thousands who were not merely descendants of the ‘ancient Christians’, but had kept the faith alive as an underground church for seven generations. Yet precisely this discovery was made, beginning in March 1865 in Nagasaki, when Father Bernard Petitjean met a group of clandestine Christians at the door of his newly consecrated church in Oura:

In March 1865 in Nagasaki, Father Bernard Petitjean met a group of clandestine Christians at the door of his newly consecrated church in Oura. They were the first ‘hidden Christians’ to be discovered.

Urged no doubt by my guardian angel, I went up and opened the door. I had scarce time to say a Pater when three women between fifty and sixty years of age knelt down beside me and said in a loud voice, placing their hands upon their hearts: ‘The hearts of all of us here do not differ from yours.’47

The initial joy on discovering these communities soon gave way to two pressing practical needs. The first was to preserve the safety and anonymity of those discovered, because in the turbulent atmosphere that accompanied the Meiji Restoration a new wave of persecution had begun that would continue for 15 years until religious toleration was granted in 1873. The second requirement was to reconcile the underground believers’ beliefs and practices with the teachings of the Catholic Church. This proved to be surprisingly difficult and in many cases impossible. The underground faith appeared to the missionary priests to be so riddled with Buddhism, Shintō and strange folk practices that its Christian element had all but disappeared. Nor did the attitude of the priests themselves help matters. They practised nothing of the accommodative method of the 16th-century Jesuits, and their rigidity provoked confrontation. The result was that while many ‘hidden Christians’ accepted conditional baptism and rejoined the Catholic Church, many thousands did not. As far as they were concerned, they had preserved the true teachings entrusted to them by Xavier and his followers. These people turned their backs on the new missionaries and stayed in their own faith communities. After 1873 they had no need to be senpuku Kirishitan any longer, but if not now exactly secret, they stayed separate, private and hidden from the outside world as Japan’s Kakure Kirishitan (The Hidden Christians).48

Several communities of Kakure Kirishitan still exist in the remote islands of western Japan. Their numbers have been dwindling for decades and it cannot be long before their ritual objects are displayed only in the museums of Christianity that have been set up on Hirado and Ikitsuki. Until then the private communities will continue to gather in their members’ homes for rituals and worship that provide a valuable insight into the underground practices of the Tokugawa Period. One fascinating example of Kakure life is the sung prayers that are chanted during ceremonies. Professor Tagita, researching the Kakure in the 1920s, was the first man to study their prayers. He was told that the sung prayers were effectively nonsense syllables designed to confuse anyone who heard them chanting. Tagita transcribed what they had been singing to him and took the text back to the university. When he sat down and stared at it he realized that for the past 250 years, without knowing it, the Hidden Christians had been singing in Latin.

An otenpesha of the Kakure Kirishitan. This was originally a straw whip used for flagellation, but lost its significance during the time of secrecy and persecution, and is now used in much the same way as a Shintō priest’s gohei.

The Kakure’s blending of elements of Buddhism, Shintō, folk religion and Christianity into a syncretic expression, a process that horrified the French missionaries in the 1850s, now excites respect for the evidence it produces of how a Christian community, cut off entirely from the outside world, could preserve anything at all for two and a half centuries. Every worship session on their calendar ends with a communal meal. This has echoes of Shintō practice, but also reflects the need to conceal their activities from official investigation. The graves of their martyrs resemble Shintō shrines in almost all particulars, while certain holy objects have acquired new uses and significance. For example, one devotional practice recommended by the Jesuits was flagellation, so we find straw flagellant whips called otenpesha on the Kakure altars, although they are no longer used as whips but in a way similar to the Shintō priest’s gohei, the paper wand with which blessings are given.

In some cases both the ritual and the object have changed so much that the combination has almost acquired a significance of its own. Rosaries would have been very incriminating objects if found during a raid. Nowadays we may find a rosary on a Kakure altar. It may have been kept for centuries at great personal risk, or simply acquired early in the 20th century, but on Ikitsuki it is more common to note little crosses of white paper, because if anyone was suspicious of what was going on, you could pop it into your mouth and swallow it. The crosses (omaburi) are made during a special service and blessed by being sprinkled with holy water. Even the water has profound significance. Having no priests to make water holy for them, the underground believers of Ikitsuki obtained supplies from a fresh water spring on the tiny rocky island of Nakae no shima. This was the site of several acts of martyrdom early in the 17th century, so the association with the martyrs is believed to make the spring water, called San Juan sama, into holy water.

A Kakure Kirishitan altar in a private house on Ikitsuki. On display are flasks of holy water, rosary beads and a paper cross called an omaburi.

So far, so Catholic – but there is also a strong element of belief in evil spirits within the Kakure Kirishitan communities, and rituals exist to deal with them. In a number of rites practised on Ikitsuki, homes, fields and cowsheds are purified using some or all of the three holy objects just described. First the otenpesha is waved to chase away the evil spirits, then the area is cleansed using holy San Juan sama water, and finally an omaburi cross is left to ensure that the evil spirits do not return.49

Such rituals, of course, speak of Shintō and seem to disprove the claims the underground Christians made to the French missionaries that they were preserving the authentic teaching of the Jesuits. But were they so far from the mark? How well did the average 19th-century French prelate understand the religious world of the 16th century, where devils, demons and witches were believed to roam and had to be controlled? An examination of what people actually believed and did in 16th-century Europe, as distinct from what the Church either said they did, or said they should have done, shows among other things that the uses of holy water went far beyond that of baptism and blessing. In 1623 parishioners in Brindisi were advised to keep holy water at home for ‘chasing away demons and all their tricks’.50 The pre-Reformation English parish clerk could earn a ‘holy water fee’ by sprinkling it on the hearth to fend off evil, and in cowsheds, fields and even on the marriage bed to ensure fertility.51

The Kakure pantheon, which takes in Jesus, the Virgin Mary, saints and martyrs along with Shintō kami, is charmingly illustrated in this picture of the Annunciation, showing God, the Virgin, Jesus (already born!) and the angel Gabriel as a tengu. All these strange features are due to the total isolation the underground church experienced for over two and a half centuries.

The sacred mikoshi of the Hime shrine on Ikitsuki is carefully guided down the flight of steps and between the shrine’s torii gate during the annual festival.

But if the Kakure faith resembles 16th-century Catholicism in this respect, then it is very different from it in at least one other crucial aspect. This lies in the identification of the ‘evil spirits’ whom the Kakure rituals are designed to thwart. These evil spirits are certainly not the kami of Japan, who are instead respected and venerated in a Kakure pantheon that takes in Jesus, the Virgin Mary, saints and martyrs. This belief is in marked contrast to their 16th-century forebears, who performed rites of exorcism against evil spirits that on expulsion announced their true identity as Japanese kami whom the Christian God had driven from their thrones.52 It was this total identification of the kami with devils that led to the ruthless destruction of temples and shrines by the first converts.

One remarkable feature of the Hime shrine’s annual matsuri occurs when the Shintō priest follows the mikoshi on to the site of Christian martyrdom known as Senninzuka, and prays there in front of the shrine.

The survival of the underground church showed that, when there was no other alternative, Christianity could change in the Japanese environment – just as every other religion had done – even if the ultimate price was the mutual rejection of each other when the missionaries returned. Compromise had been necessary under persecution, and had to some extent come about naturally in the Japanese environment where, for example, non-Christians in a locality venerated sites of martyrdom like Danjikusama as the abode of powerful kami. This attitude made life easier for a hidden Christian who wished to remember his martyred relatives. The most moving illustration of this is the Hime-jinja shrine in Ikitsuki, the Shintō shrine where the general had prayed before going to massacre the inhabitants of the island in 1645. Every year they have a matsuri (festival), where they carry the mikoshi through the streets of the town, just like any Shintō festival anywhere in Japan. But this one has a strange feature to it, because it is taken through the torii of the martyrs’ site of Sennizuka: ‘the mound of the thousand dead’. The mikoshi is placed in front of the shrine of the martyrs and the priest kneels there and prays in front of them. This combination of a Shintō matsuri with a place holy to martyrs who were secret Catholics, which is now preserved by the separated Kakure Kirishitan, sums up another great truth about Japanese religion: that somewhere in the ‘religious supermarket’ there is a place for everyone.