ONE

Introduction

Armed conflict has always played an important role in Chinese history. Most of China's imperial dynasties were established as a result of success in battle, and the same may be said of the Nationalist (Guomindang KMT) and Communist regimes in the twentieth century. Periods of dynastic decline were marked by great peasant rebellions, and the collapse of central authority repeatedly gave rise to prolonged, multicornered power struggles between regional warlords.

Questions of military institutions and strategy have always occupied a prominent place in Chinese political thought, and the armed confrontation between the sedentary Chinese state and the nomadic peoples of the Inner Asian steppe was one of the most fundamental themes of Chinese history prior to the twentieth century.

China's modernization efforts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were stimulated by repeated defeats at the hands of the Western powers (and later Japan), beginning with the Opium War of 1839-1842, and by the need to respond to the challenge of domestic rebellions such as that of the Taipings (1850-1864). Indeed, it is arguable that the pursuit of “wealth and power” has been a common denominator of all Chinese regimes from the twilight of the Qing dynasty to the People's Republic (PRC) in the post-Deng era.

In spite of this history, the existing literature has tended to neglect or downplay the role of war and the military. Works on premodern China have emphasized (and reflected) the Confucian pacifism and antimilitary bias of the scholar-official class, while the literature on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries gives pride of place to intellectual, cultural, and political developments. The English-language literature on Chinese military history, ancient or modern, is extremely limited; for premodern China in particular, there is only a handful of books, several of which are now out of print. This volume is intended to fill the gap by offering a wide-ranging overview of the major themes, issues, and patterns of Chinese military history, from the first millennium B.C.E. to the present day. It is designed to provide nonspecialists and newcomers to the subject with basic orientation in fifteen key areas, and each chapter concludes with suggestions for further reading and research.

THE LAY OF THE LAND

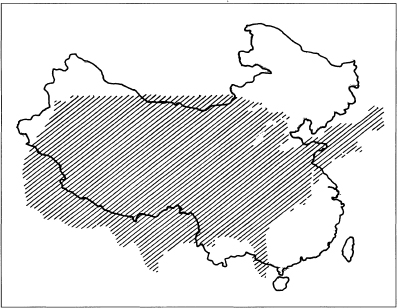

The People's Republic of China covers roughly the same land area as the United States, and is somewhat larger than Europe (from Moscow west to the Atlantic). In contrast to the United States and Europe, however, China is not richly endowed with arable land. Most of the country's territory is mountain, desert, or arid plateau, and there is no counterpart to the vast arable expanse of the American Midwest. The largest zone of flat, fertile land, the North China Plain along the lower reaches of the Yellow River, is only a little larger than than the combined land area of Illinois and Iowa. In southern and western China, arable land (and human population) is concentrated in the much smaller river valleys and coastal lowlands. Population is especially sparse in the vast, arid western territories of Xinjiang, Tibet, and Qinghai, which account for nearly half of China's total land area. The country's highest mountains are found in the far west, in the Himalaya and Pamir ranges along the fringes of the Tibetan plateau, and the greatest rivers, the Yellow and the Yangzi, flow eastward from the Tibetan highlands to the Pacific Ocean. These western territories were little touched by Chinese settlement until very recent times. Together with the Gobi Desert in today's Mongolia, they formed an all but insurmountable barrier to the westward and northward expansion of the sedentary, agricultural lifestyle of the Han Chinese.

For most of China's history, these western and northern territories were left in the hands of peoples whose languages, cultures, and ways of life were dramatically different from those of their Han neighbors. Some, such as the Iranian and Turkish oasis dwellers of Xinjiang and the Tibetans of the Yarlung Zangbo (Brahmaputra) valley, were small-scale agriculturalists, but the dominant mode of livelihood was pastoral nomadism. The outer regions were linked to the Chinese heartland by the exchange of horses and other livestock for the products of China's farmers and artisans, including grain, silk, and metalware. Trade in luxuries extended even farther, along the fabled Silk Road that connected China with the Middle East and the Mediterranean world. Given the vast distances, harsh landscapes, and tough customers along the way, however, there was very little direct contact between the two ends of the Eurasian landmass before Europeans found their way to China by sea in the early years of the sixteenth century.

Map 1.2 Relative size of China and the 48 contiguous United States. Adapted by Don Graff based upon Interpreting China's Grand Strategy, Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2000)

The territory of today's China can be divided into two zones. The first, “China proper,” was and is densely populated, agricultural, and inhabited mainly by the Han majority; in imperial times its people were ruled directly by the Son of Heaven. The second zone consists of Tibet, Qinghai, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and the three Manchurian provinces; in earlier times this zone also included the territory that is now the independent republic of Mongolia. These lands were (and in some cases still are) very sparsely populated and inhabited by non-Han ethnic groups. At some times in Chinese history these areas paid tribute to the Middle Kingdom and were treated as vassal states; at other times, however, they were fiercely independent and threatening. The power of China in this region has fluctuated greatly over the centuries. The Former Han and Tang dynasties dominated Xinjiang, but Song and Ming did not. Tibet was first attached to the empire by the Mongol Yuan dynasty, but recovered its independence when the Yuan gave way to a new native Chinese dynasty, the Ming. Today's PRC owes its shape largely to the Manchus, who conquered China and established the Qing dynasty in 1644. They brought their own homeland, Manchuria, into the empire, and went on to subdue Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Of this Qing legacy only “outer” Mongolia has been lost, primarily as a result of Russian pressure in the early part of the twentieth century.

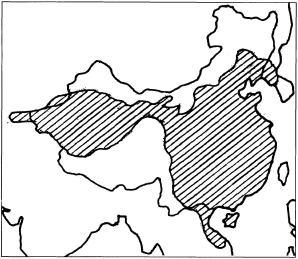

The theater in which Chinese military history was acted out included not just the territory of today's China (and Mongolia), but covered a vast, subcontinental region of East Asia. The Korean peninsula was administered as an integral part of the Han empire, and was the scene of Chinese military interventions by the Sui and Tang dynasties during the seventh century, by the Ming dynasty in the 1590s, by the Qing in the 1890s, and by the Communists in the 1950s. Northern Vietnam, including today's Hanoi, was ruled by the Qin, Han, and Tang dynasties, and Chinese armies sometimes penetrated even farther south. Han and Tang armies pushed deep into what is now the territory of the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. Mongol-led forces based in China invaded Japan, Burma, and Java in the thirteenth century, and a Qing army marched into Nepal in the 1790s. In the first half of the fifteenth century the Ming “treasure fleets,” led by Zheng He and his associates, explored the Indian Ocean littoral, and in the last three decades the People's Republic has been striving to establish its military dominance in the South China Sea. In periods when China was united and strong, most military encounters took place along the periphery as the country's rulers sought to assert their suzerainty over neighboring states and peoples. During periods of division and civil war, on the other hand, the locus of most military action was the densely populated heartland of “China proper.”

RESOURCES AND INFRASTRUCTURE

In ancient and imperial times, the Chinese heartland was richly endowed with the resources needed to support military endeavors. First and foremost among these resources was China's large population, recorded at more than 56 million by the Han census of 157 C.E., when the population of the Roman Empire was not more than 46 million. During the Song period China's population rose to an estimated 120 million, and between 1650 and 1850 it is believed to have tripled to 410 million.1 These numbers made it possible for the country's rulers to maintain very large military establishments, nearly a million men in the early ninth century and possibly as many as four million under the late Ming. The vast majority of the people, however, were farmers who provided the grain that was needed to feed the troops. When necessary they could be pressed into service as porters for the army, and as corvée laborers they built the roads and canals over which the imperial army moved and the city walls and frontier fortifications that buttressed the defense of the realm. In some periods women as well as men might be called up for labor service.

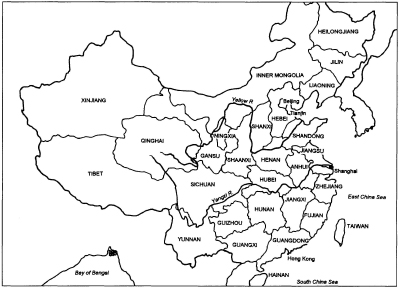

Map 1.3 China's provinces in the second half of the twentieth century. Adapted by Don Graff based upon Interpreting China's Grand Strategy, Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2000)

Other resources provided the materials for the instruments of war. Timber from the mountain fringes of the Sichuan basin made possible the construction of the great river flotillas that swept down the Yangzi to conquer the south in 280 and 589, and the forested hills of the Yangzi watershed and the coastal provinces of Zhejiang and Fujian provided for the huge treasure ships of Zheng He's fleet in the early Ming. Under the Northern Song dynasty, deposits of iron in Shandong, northern Jiangsu, and the Henan-Hebei border region were the basis for an arms industry that supplied China's soldiers with spearheads, arrowheads, swords, helmets, and armor for both man and horse. In the early eleventh century, foundries in these areas not far from the capital city of Kaifeng were producing 58,000 tons of iron a year, much of which went to meet the needs of the military.2

The Chinese heartland was wanting in regard to only one of the essential tools of premodern warfare. Its forested mountains and densely populated farmland were not well suited for the raising of horses, and this was especially true of the warmer and wetter lands south of the Yangzi River. Although the great majority of Chinese soldiers through the ages marched and fought on foot, cavalry forces were vital because they provided a powerful offensive element on the battlefield and they alone were capable of keeping up with highly mobile nomadic opponents. When imperial control extended over the grasslands of the steppe margin, state herds of as many as 700,000 head (as in the middle of the seventh century under the Tang dynasty) provided the basis for cavalry forces that extended the emperor's authority to even more distant regions. When control over the pastures was lost, however, the cavalry component dwindled and Chinese armies found themselves at a grave disadvantage against mounted opponents.

On the defensive, at least, investment in infrastructure made possible by China's vast human and material resources could compensate for a shortage of horses. Towns and cities were surrounded by massive walls built of stamped earth (hangtu), and the same method was used to construct the early versions of the northern frontier fortifications that became known as the Great Wall. During the Song and Ming periods, fortifications became more elaborate and walls acquired facings of stone or brick. Some of these city walls still had defensive value as late as the Civil War of 1946-1949. Since water transport was by far the most cost-effective means of moving bulky goods in premodern times, imperial governments also devoted considerable attention to augmenting and connecting China's rivers with man-made canals. The most famous of these, the Grand Canal, was first opened by the Sui dynasty at the beginning of the seventh century to connect the Lower Yangzi region with the Yellow River and the area around today's Beijing; carefully maintained by subsequent dynasties, parts of the canal remain in use today. State granaries were established at key points on the riverine transportation network, both to provide for the needs of military campaigns and to give relief to the population in the event of famine.

It was only after the Western imperialist onslaught began in the Opium War of 1839-1842 that the military resources and infrastructure characteristic of more than two thousand years of Chinese history began to see significant changes. Steam-powered vessels gave the British and other foreign interlopers easy access to China's internal waterways, which now became avenues for invasion. The climax of the Opium War came when water-borne British forces cut the Grand Canal where it meets the Yangzi at Zhenjiang, then moved upstream to attack the city of Nanjing. Foreign warships would continue to ply China's rivers until Communist field artillery denied HMS Amethyst passage of the Yangzi in 1949. By the last decades of the nineteenth century, China's most capable statesmen and military leaders were well aware that the empire would have to adopt key Western technologies in order to defend itself effectively. These included not only steamships and modern rifles and artillery, but also the railroad and the telegraph. The first Chinese steamships were built in the 1860s, but telegraphs and railroads—far more intrusive presences in the ancestral landscape—had to wait much longer. A short railway line built by foreigners near Shanghai in 1876 was purchased and dismantled by Qing authorities the following year, and it was not until after 1900 that China's first major trunk lines were built. The telegraph (and later telephone and wireless communications) allowed closer control and better coordination of armed forces, and the railway held out the hope that the country could be more effectively defended by forces operating on interior lines. The railway was a two-edged sword, however. Fears that foreign-financed and -controlled rail lines would permit foreign penetration of the Chinese hinterland contributed to the mood of crisis that preceded the Wuchang Uprising of 1911, which precipitated the fall of the Qing dynasty. The nation's rail network did indeed facilitate the Japanese invasion and occupation of eastern China in 1937-1945, but at the same time the invaders found their communications, logistics, lines of advance, and zones of occupation tied to the railway lines. The new technology offered unprecedented opportunities, but also imposed its own constraints on military operations.

Map 1.4 A Strong dynasty: Han circa 100 B.C.E. Adapted by Don Graff based upon Interpreting China's Grand Strategy, Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2000) p. 42

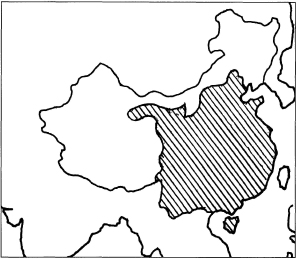

Map 1.5 A weak dynasty: Ming circa 1640 C.E. Adapted by Don Graff based upon Interpreting China's Grand Strategy, Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2000) p. 42

The new prominence of steamships and railways from the late nineteenth century onward required the exploitation of new resources, most notably coal. Several areas of northern China (particularly Shanxi province) were found to hold rich reserves of coal, which remained an important fuel source even at the end of the twentieth century. As late as 1980 there were still some 10,000 steam locomotives operating in China, and diesel and electric locomotives will not likely bury the last steam engine until the second decade of the twenty-first century. Military aviation (from 1913) and motor vehicles demanded another sort of fuel. For more than two decades, China's need for oil was largely met by the great oilfield opened at Daqing in Manchuria in the early 1960s. Today, however, China no longer produces all of the petroleum needed by its rapidly growing economy, and the quest for new oil reserves is an important factor behind the assertion of sovereignty over the South China sea. Initially dependent on waterborne transit, China turned to rail transportation in the twentieth century and is only now beginning to create a modern highway system.

In spite of these changes, Chinese military logistics in the twentieth century did not represent a surgical break with the imperial past. Mao's armies in 1949 still moved in the traditional manner, by horse and foot, and many PLA units continued to rely on horse, donkey, and even camel transport long after the establishment of the People's Republic. Even without considering China's relative poverty, labor-saving devices did not always make sound sense. As the Chinese intervention in Korea in the winter of 1950-1951 showed, packing supplies in by porters who could disappear in the daytime was more effective than hauling things in train and truck convoys easily detected by the enemy's aerial reconnaisance. And the size of China's population (1.158 billion in the 1992 census and about 1.3 billion in 2001) meant that labor was always cheap relative to capital equipment. In recent years, however, China's large population has come to be regarded more as a burden than an asset. The country is no longer self-sufficient in grain, and the imposition of birth control policies reflected the fear that economic advances and improvements in the standard of living would be eaten up by population growth.

An additional resource needs to be mentioned, one that was by no means unimportant in premodern times and has become essential in today's world of high-technology warfare: educated, literate, highly skilled, and innovative personnel. Clerical personnel were a presence in Chinese armies throughout the imperial period (as evidenced, for example, by the Han-period documents of military administration recovered from Edsen-gol in Inner Mongolia), and the spread of woodblock printing during the Northern Song period must have led to an increase of popular literacy. Well-known Chinese innovations of the imperial period included not only printing, but also paper, gunpowder, and the mariner's compass. After 1500 C.E., Chinese technology began to lag behind that of the West, probably due more to revolutionary developments in Europe than stagnation in China. After the middle of the nineteenth century, however, the Chinese began to master one Western technology after another, from the steam engine and the telegraph to jet aircraft, the atomic bomb, and intercontinental ballistic missiles. The gap has not been entirely closed today, but it is clear that the West's continued technological superiority is now dependent on continuing innovation.

ACTORS, INTERESTS, AND INSTITUTIONS

The idea of the proper relationship between the soldier and the farmers who made up the vast majority of the population has been reformulated many times over the course of Chinese history. During the Spring and Autumn period (722-481 B.C.E.) warfare was mainly the province of aristocratic elites, but during the Warring States (453-221 B.C.E.) and Han (202 B.C.E.-220 C.E.) periods huge armies were formed from peasant conscripts. Later periods saw the appearance of hereditary military households and “militias” of farmer-soldiers, such as the fubing of the Tang dynasty. From the eighth century onward, a long-service, mercenary soldiery distinct from the farming population tended to predominate, even as scholars sang the praises of the sturdy (and inexpensive) yeomanry of earlier times. Throughout the history of imperial China, an important role was played by specialized units recruited from among non-Han peoples both within and outside the borders of the empire; these included aboriginal infantry from the mountains of the south and cavalry raised from the nomadic peoples of the steppe frontier. During some periods (such as the early Tang), steppe allies and auxiliaries made a decisive contribution to the expansion of Chinese power, and at some times (most notably under the Mongol Yuan) warlike steppe peoples were themselves rulers of China.

It is testimony to the extreme diversity of military institutions in China's imperial past that the twentieth century brought little that was entirely new, at least in the way of recruitment and terms of service. The men of early Republican and warlord armies were generally long-serving regulars recruited for pay, much like the soldiery of late Tang and Song times. The Nationalist government began to introduce a European-style conscription system in the mid-1930s. During the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1945 this tended to degenerate into brutal press-ganging, but the original conception (and the system put in place in Taiwan after 1949) bore a remarkable resemblance to the cadre-conscript system of the early Western Han, with a relatively short period of active service followed by a much longer time in the reserves. The People's Republic of China has also adopted a conscription system, though the sheer size of the population and the fact that during the Mao years military service offered one of the very few paths of upward mobility for young peasant males meant that men who were not willing volunteers were seldom called upon to serve. The ancient ideal of the farmer-soldier was revived in the militia system of Mao's China; in the mid-1970s there were reported to be 15 to 20 million people, both men and women, enrolled in the “basic” militia.

This brings us to the understudied subject of women in Chinese warfare. Women were, of course, always present as victims and as support personnel (much in evidence, for example, in the labor gangs that built airfields for U.S. bombers in the 1940s). At times, however, they were much more active participants. There is evidence that a Shang dynasty queen led military campaigns around the beginning of the twelfth century B.C.E., and nearly two thousand years later a daughter of the founder of the Tang dynasty raised forces to support her father's bid for the throne. At the other end of the social hierarchy, charismatic shamanesses emerged from time to time to lead peasant rebellions. The story of Mulan, the young woman who took her father's place in the ranks, may be fiction, but actual women have been participants in combat. The Taiping rebels in the mid-nineteenth century organized military units composed entirely of women, and women served—and fought—with the Red Army on the Long March. Approximately 135,000 women are serving in the People's Liberation Army today, though as in most other contemporary military establishments they are assigned to support rather than combat roles.

Military leaders were recruited in a variety of ways in different periods of Chinese history, and came from a wide range of backgrounds. During the Han dynasty, some of the most prominent commanders were kinsmen of imperial consorts who received appointments on the basis of their connections rather than any obvious aptitude for command. In some periods, such as the Sui and early Tang, military and civil elites were not sharply differentiated, and members of powerful aristocratic families might hold both civil and military positions in the course of an official career. A sharper distinction between civil officials and military officers had appeared by the middle of the Tang period, however, and continued to be evident under most of the later dynasties. Men from elite, landowning families tended to pursue careers in the civil bureaucracy; these required a high level of literacy and considerable book learning, since recruitment was usually by means of a very demanding series of written examinations. Military officers, on the other hand, tended to come from more humble backgrounds. They were often promoted from the ranks, and many were illiterate or semiliterate at best. The Tang, Song, Ming, and Qing dynasties did offer military examinations, but these tended to emphasize horsemanship and archery more than knowledge of military texts. Civil bureaucrats and military officers were often rivals for influence at court, and the civil officials attempted to assert their dominance over the military sphere in various ways and generally had the upper hand. Civil officials with no practical military training or experience of command at the lower levels were sometimes sent out to direct military campaigns. One such scholar-general was the Ming philosopher Wang Yangming (1472-1529); another was Zeng Guofan, the victor over the Taiping rebels in the mid-nineteenth century.

The behavior of Chinese rulers was congruent with the superiority (if not absolute supremacy) of civil over military elites. Most emperors never acted as generals or led their armies in battle, and the exceptions were mostly dynastic founders, who were often military men from humble origins who had battled their way to the throne. Civil officials usually held the view that an emperor was too valuable an asset to be risked on the battlefield (his defeat or capture might be interpreted as signalling the loss of Heaven's mandate), and that his principal function was to preside over the ritual of imperial government in the capital. Even Wudi, the “Martial Emperor” of the Han dynasty who launched repeated expeditions against the nomadic Xiongnu, never led a military campaign in person.

The training and recruitment of Chinese military leaders changed considerably in the early twentieth century. Military academies such as Baoding and Whampoa were set up in imitation of Western models, and as a consequence growing numbers of officers could boast a modicum of modern, professional training. At the same time, however, this professionalizing trend was offset to a considerable extent by the vicissitudes of Chinese politics. The breakdown of civil authority during the warlord period threw political power into the hands of military leaders, and the rise of two great revolutionary parties, the Guomindang and the Chinese Communist Party, that sought to take and hold power by means of armed force further blurred the distinction between civil and military leadership roles. The Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek was both generalissimo and head of state, and many Communist leaders (such as Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping) worked both sides of the civil-military divide. It has only been in the last two decades that maturation and routinization of the political systems in both Communist China and Taiwan have produced a distinctly civilian political leadership and confined military leaders to their professional sphere.

IDEOLOGY AND STRATEGY

In recent years there has been much interest in the qualities and characteristics that have made the Chinese approach to warfare different from that of other societies (especially the European and European-descended societies usually labelled as “the West”). Some authors, pointing to the Confucian tradition and certain passages in Sunzi's Art of War, have argued that China's traditional grand strategy has emphasized defense over offense and displayed a preference for nonviolent solutions to security problems. Sunzi, after all, tells us that the acme of military excellence is to subdue the enemy without fighting, while the Mencius, one of the core texts of the Confucian canon, maintains that the truly virtuous ruler, by means of his transforming influence, can bring his enemies to submit voluntarily without recourse to physical coercion. Others, most notably the Western military historian John Keegan, have argued that China has followed an “Oriental” style of warmaking characterized by caution, delay, the avoidance of battle, and the use of elaborate ruses and stratagems. This style of warfare is contrasted with a “Western way of war” that stresses direct, face-to-face confrontation and the rapid resolution of military conflicts by main force.3

Setting aside momentarily the question of whether these are accurate representations of either the Chinese or Western approaches to warfare, strategy anywhere in the premodern world had necessarily to be shaped within the bounds of a common set of material constraints. The management of campaigns had to take into account when in the spring the grass would be long enough to sustain the horses, how much surplus grain would be in the granaries, and when the rivers would flood and be impassable. In all periods up almost to the present, armies were limited to about thirty miles a day if mounted and fifteen if on foot, but even these rates of march required an excellent supply or foraging system. Horses required twenty-six pounds of forage and fifty gallons of water a day, and each soldier needed approximately three pounds of grain. East or West, an army was a veritable vacuum cleaner scouring up the resources of the surrounding countryside; its presence might easily lead peasants to hide their sustenance and flee to cover. Very large armies could only be supplied by water transport, and thus had great difficulty moving far from rivers, canals, and seacoasts.4 This explains why campaigns were limited geographically and seasonally. In both Europe and China, transportation and supply dictated that the areas most likely to be fought over were the great river valleys and the arable plains.

The difference between premodern warfare in China and the West was probably not as great as prescriptive texts such as the Chinese military classics might lead us to believe. Despite the literary emphasis on caution and avoidance of the risks of combat, battle was no less common an occurrence in imperial China than it was in the ancient Mediterranean world or medieval Europe. The Greeks and Romans made use of stratagems just as the Chinese did, and writers who see a distinctive “Western way of war” do not take into account the reluctance of medieval Byzantine and Latin commanders to risk their armies in pitched battles. Moreover, the contents and recommendations of the principal Byzantine military treatises bear a remarkable resemblance to their medieval Chinese counterparts. There are other points of similitarity. In his recent study of Chinese strategic culture, the political scientist Alastair Iain Johnston found that the Chinese military classics (including Sunzi) show a preference for violent, aggressive solutions to security problems—provided that one has the capability to carry them out. He also found that the military activity of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) corresponded to what might be predicted by a Western realpolitik or “structural realist” model of state behavior: In its early years, when the state was militarily powerful, Ming China engaged in far more campaigns against its neighbors than was true later on, after the regime and its armed forces had begun to weaken.5

A cursory examination of the military history of other major dynasties, such as the Han and Tang, would seem to reveal much the same pattern. It was during their vigorous early or middle years that these regimes launched offensive campaigns to dominate peripheral regions such as Korea, Vietnam, Xinjiang, and the Mongolian steppe. As the dynasties began to weaken and internal problems arose, however, the aggressive use of military force tended to be replaced by other strategies emphasizing diplomacy, appeasement, and the construction of static defensive installations. What Johnston calls “the Confucian-Mencian paradigm” was not entirely without influence, however. Within the ruling circles of the empire, support for aggressive military action tended to come from strong emperors, groups closely connected to the throne such as consort families and eunuchs, and aristocratic and military elites. Opposition to such strategies, on the other hand, was most likely to come from scholar-officials educated in the Confucian tradition. They blamed the Han emperor Wudi for wrecking the economy of the empire with his repeated campaigns against the nomadic Xiongnu, and opposed Tang Taizong's attempt to subdue the northern Korean kingdom of Koguryo in the middle of the seventh century. Their attitude probably derived in part from the Confucian belief that the need to use force was a sign of the failure of virtue, and in part from a desire to restrain the power of rival elites (such as military men and eunuchs).

In contrast to the antimilitary bias evident in China's heavily Confucian elite culture, some have pointed to a more favorable attitude toward things martial in Chinese popular culture. They note such things as the widespread practice of martial arts in the cities and villages and the popularity of operas, folktales, and works of fiction dealing with the exploits of martial heroes.6 It is important to note, however, that these heroes are usually Robin Hood-type social bandits rather than regular soldiers in the service of the state. Ordinary people in many cases took extreme measures (including self-mutilation) to avoid being conscripted for military service, and soldiers were often regarded (with good reason) as being little better than brigands. In the twentieth century, the Chinese Communists largely succeeded in overcoming the negative image and making soldiers respectable by holding them to higher standards of behavior and emphasizing the unity of army and people.

THE LITERATURE

China can claim a very ancient tradition of writing about war. The thirteen chapters attributed to Sunzi, probably China's earliest surviving military treatise, are thought to date from the fifth century B.C.E., and the author of the Sunzi appears to quote from an even earlier work on the art of war that is now no longer extant. Many other military manuals were written in later centuries, and full-blown military encyclopedias appeared during the Song and Ming dynasties (some two thousand years after Sunzi's time).

When it comes to the description of actual military events as opposed to the prescriptive contents of the treatises, however, the Chinese corpus of military literature is much less impressive. The battle narratives and other descriptions of military operations that we find in the dynastic histories tend to be laconic in the extreme; such matters as weapons, tactics, detailed orders of battle, and logistics are largely neglected, while the attention of the historian is drawn to clever and unusual stratagems. A fair amount of space is devoted to the councils of war held before and after a battle, but in between them the account of the combat itself may be no more than two or three sentences. This pattern is already evident in such pioneering early histories as Sima Qian's Historical Records (Shiji) of circa 100 B.C.E. and Ban Gu's History of the Former Han Dynasty (Han shu) dating from the first century C.E.

This state of affairs can be explained by the gulf that usually existed between scholars and soldiers in imperial China. History was written by elite scholar-officials who seldom had any military experience. They had little interest in the technical details of warfare, and preferred to focus on matters of statesmanship, ethical behavior, and moral principle. Military leaders, on the other hand, were often poorly educated or even illiterate. These men and their activities were viewed with distaste by the scholar-officials, who tended to subscribe to the Confucian view that the use of violence represented a failure of statecraft and indicated that its user might lack the virtue needed for governance by moral suasion.

While neglecting the details of military operations, traditional Chinese historians nevertheless displayed considerable interest in military institutions. Beginning with Ouyang Xiu's New Tang History (Xin Tangshu), written in the eleventh century, the Chinese dynastic histories include chapters on the military that address such matters as organization, recruitment, and terms of service. Unlike combat itself, military institutions were seen as a worthy object of scholarly attention. This attitude no doubt owed something to the fact that the scholars writing the histories were also government officials, and military administration—as opposed to combat command—was always an important responsibility of the civil bureaucracy in imperial China. Beyond this, however, military institutions were considered to be a vitally important area of imperial policy and one that could be directly linked to the rise and fall of dynasties; great significance was often attached to the means of recruitment and the nature of the relationship between the soldier and civilian society as a basis for military power and dynastic stability. These attitudes have shown remarkable staying power. Even in the twentieth century, much of the finest Chinese scholarship on military history—such as Gu Jiguang's work on the Tang fubing militia, Luo Ergang's study of the Qing Green Standard Army, and Wang Zengyu's work on the Song military—has been devoted to military institutions.7

The volume of Chinese writing on military history has increased tremendously since the middle of the twentieth century, and this is especially true with regard to accounts of military operations. This may be seen both as a consequence of China's experience of almost constant warfare between 1911 and 1949 and as a product of Western influence insofar as a significant portion of this literature has come in the form of officially sponsored staff histories imitating the compilations published by the major belligerents following the two world wars. A typical example of this genre is the massive History of the Nationalist Revolutionary Wars (Guomin geming zhanzheng shi) compiled between 1970 and 1982 under the auspices of Taiwan's Armed Forces University. Similar works, such as the three-volume Battle History of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (Zhongguo renmin jiefangjun zhanshi), have been issued by the PRC.8 The same style has also been applied to the military history of imperial times, as, for example, in the ten-volume History of Warfare in China through the Ages (Zhongguo lidai zhanzheng shi) published in Taipei in 1967 and the twenty-volume Comprehensive History of Chinese Military Affairs (Zhongguo junshi tongshi) published in Beijing in 1998. The last several decades have also seen an outpouring of memoir literature from former soldiers on both sides of the Taiwan Strait.

In contrast, relatively little work on Chinese military history has been published in English and other Western languages. Among the most important contributions in English are William W. Whitson's The Chinese High Command, a monumental history of the People's Liberation Army; Chinese Ways in Warfare, a pioneering collection of case studies of military operations in imperial China edited by John K. Fairbank and Frank A. Kierman Jr.; and the volumes on traditional military technology prepared by Joseph Needham and Robin Yates for Science and Civilisation in China.9 In general, however, the level of sophistication found in writing on Chinese military history in both Chinese and English has not matched that in other fields of military history. For the most part, the ideas of innovative Western military historians, from Hans Delbrück to John Keegan and Martin van Creveld, have yet to be applied to the study of Chinese warfare.

As already stated, the goal of this volume is less ambitious. It offers an introduction to fifteen of the major topics in Chinese military history from antiquity to the present day. Given the vast size and scope of the subject, a truly compehensive treatment is out of the question in a single volume. Many matters of great importance—such as arms production, logistics, the role of women in warfare, the use of divination and other “magical” techniques on the battlefield in ancient and imperial times, popular attitudes toward the military, and the recruitment and training of martial elites—receive little attention in this book, and some have yet to be thoroughly explored anywhere. The field is still to a very large extent wide open, and if this volume succeeds in stimulating further research it will have more than accomplished its purpose.

NOTES

1. Tang Changru, Wei Jin Nanbeichao Sui Tang shi san lun [Three discourses on the history of Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties, Sui, and Tang] (Wuhan: Wuhan daxue chubanshe, 1993), 29-30; John K. Fairbank and Merle Goldman, China: A New History, enl. ed. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1998), 89; Susan Naquin and Evelyn Sakakida Rawski, Chinese Society in the Eighteenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 24-25. For the Roman population, see Colin McEvedy and Richard Jones, Atlas of World Population History (New York: Facts on File, 1978), 21.

2. Robert Hartwell, “Markets, Technology, and the Structure of Enterprise in the Development of the Eleventh-Century Chinese Iron and Steel Industry,” Journal of Economic History 26 (1966): 32-33, 36, 38.

3. John Keegan, A History of Warfare (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 214, 221, 332-333, 380, 387-388; also see Victor Davis Hanson, The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

4. See Donald W. Engels, Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1978).

5. Alastair Iain Johnston, Cultural Realism: Strategic Culture and Grand Strategy in Chinese History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

6. See Morton H. Fried, “Military Status in Chinese Society,” American Journal of Sociology 57 (1951-1952): 347-355.

7. Gu Jiguang, Fubing zhidu kaoshi [Examination and explanation of the fubing system] (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1962); Luo Ergang, Liiying bingzhi [A treatise on the Green Standard Army] (Chongqing: Commercial Press, 1945); Wang Zengyu, Songchao bingzhi chutan [Preliminary investigation of the military institutions of the Song dynasty] (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1983).

8. Military History Research Department of the Academy of Military Science, Zhongguo renmin jiefangjun zhanshi, 3 vols. (Beijing: Junshi kexue chubanshe, 1987).

9. See Joseph Needham and Robin D. S. Yates, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, pt. 6, Military Technology: Missiles and Sieges (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994). A very recent addition to the literature is Bruce A. Elleman, Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795-1989 (London and New York: Routledge, 2001).