THREE

State Making and State Breaking

In its broadest outline, Chinese history is often understood in terms of a succession of great dynasties—Han, Tang, Song, Ming, Qing—and Chinese military history can be presented as the successive conflicts between those dynasties and the “barbarian” inhabitants of the Inner Asian steppe, such as the Xiongnu, Türks, Jurchen, and Mongols. Like most simplifications, this is also a distortion. The great dynasties were separated by periods of internal chaos and civil war, and for every great dynasty there were many lesser regimes to complicate the chronological tables. Some, such as the Qin (221-206 B.C.E.) and the Sui (581-618), had a major impact on Chinese history despite their brevity. Many others, such as Northern Wei (386-534), never succeeded in establishing their control over all of the historically Chinese territory inhabited by ethnic Han populations. For long periods, China's territory was divided between two or more imperial states. The competition between the Three Kingdoms of Wei, Wu, and Shu-Han covered much of the third century C.E., and the empire was divided again when barbarian invaders overran much of north China in the early years of the fourth century. This new division between north and south lasted until the Sui reunification in 589; during this time five dynasties succeeded one another in the Yangzi valley, while a bewildering profusion of ephemeral local regimes rose and fell in north China. The decline of the Tang dynasty in the second half of the ninth century ushered in yet another age of disunity. Between 907 and 960 five dynasties ruled over the north in rapid succession, while “ten kingdoms” divided the south between them. The subsequent reunification by the Song emperors lasted only until 1127, when a Jurchen invasion initiated a new period of north-south division that ended with the conquest of Southern Song by the Mongol Yuan dynasty in 1279.

Instead of revolving around the defense of an external frontier against foreign powers, China's military history is to a very large extent a record of internal conflicts. Under the loose hegemonies exercised by the Shang and Zhou dynasties, most armed struggles seem to have occurred within the territory that later came to be known as “China proper,” and were fought between groups whose descendants eventually came to regard themselves as Chinese. A well-known example is the conquest of the Shang people based in the eastern part of the North China plain by Zhou invaders coming from the Wei River valley in or around the year 1045 B.C.E. As the Zhou court weakened during the Spring and Autumn period (722-481 B.C.E.), conflict intensified between the “central states.” The Commentary of Zuo (Zuozhuan), our main source for the history of this period, has far more to say about the battles between the states of Jin, Qi, Lu, Zheng, and Chu than about the threat posed by the barbaric Rong and Di peoples. By the third century B.C.E., the scores of small states mentioned in the Commentary of Zuo had given way to only seven powers, whose attention was focused primarily on their competition with one another rather than with the horsed nomads who were beginning to appear on the northern steppe. It was this milieu that gave birth to Sunzi's Art of War and the other Chinese military classics, which assume a Chinese opponent and devote virtually no attention to the special problems of dealing with mounted nomads and other exotic foes. After the unification of China under the Qin dynasty in 221 B.C.E., the empire's internecine conflicts showed recurrent patterns that continued to be seen as recently as the first half of the twentieth century. This chapter focuses on those patterns, and on the period from the creation of China's first unified empire in 221 B.C.E. to its final collapse in 1911.

THE DYNASTIC CYCLE

The Chinese long ago identified a cyclical pattern in their history, a rhythm associated with the rise and fall of dynasties. Imperial regimes emerged out of the chaos of civil war to impose order and reunify the country. They enjoyed a period of vigor (including expansion into foreign lands) but then, after the passage of several generations, fell gradually into decline. Eventually rebellions broke out that brought down the dynasty and ushered in a new period of civil war, out of which a new unifier would emerge to repeat the process. The traditional Chinese explanation for this dynastic cycle was wrapped in Confucian moralism and rooted in the ancient concept of the “Mandate of Heaven.” Heaven gave its blessing to a dynastic founder on account of his superior virtue. When one of his royal heirs strayed from the proper path, Heaven indicated its displeasure through portents (such as comets, earthquakes, and other unusual phenomena); if he did not mend his ways, so the theory went, rebellions would break out and Heaven would transfer its support to a more virtuous leader and his new dynasty. In the Chinese dynastic histories, last emperors are often portrayed as monsters of depravity, moving from lurid orgies to acts of sadistic cruelty and all the while ignoring the tearful remonstrances of upright ministers. The archetype of the “bad last emperor” was the last Shang king, Di Xin, who invented the “roasting” punishment, arranged naked frolics amid forests of meat and pools of wine, and had one of his loyal ministers cut open to determine whether “the heart of a sage has seven apertures.”1

Modern scholars have had little use for this moralistic interpretation of the dynastic cycle, preferring to emphasize socioeconomic explanations. Circumstances were always propitious for a new dynasty emerging from a period of civil war. The slate had been wiped clean, as it were, and the dynastic founder was in a position to establish new laws and institutions and to fill his administration with new men. Rival leaders had been eliminated in the fighting, and deaths from war, famine, and disease meant that the survivors would enjoy a more favorable ratio of population to land and an improved standard of living. As time passed, however, the administrative system ossified and corruption set in. Farmland was bought up by government officials and other wealthy individuals who used their political influence to make their holdings tax exempt. This increased the tax burden on the small farmers, compelling many to abandon their holdings, which in turn drove taxes even higher for those who remained. These conditions might be exacerbated by population growth resulting from several generations of peace and prosperity, and they provided fertile ground for the peasant rebellions that would eventually bring down the dynasty. At least one modern historian has argued that the very belief of traditional Chinese scholar-officials in the dynastic cycle helped to make the pattern a reality: “When Chinese statesmen thought they discerned the classic symptoms of dynastic decline, they qualified the support they gave to the ruling house and thus contributed to its ultimate collapse.”2

Yet other scholars have taken a thoroughly skeptical view of the dynastic cycle, maintaining that the fall of individual dynasties was the result of chance events and poor policy decisions, with no underlying logic or inevitability. They may well be correct, yet it is difficult to deny that certain recurrent patterns can be discerned in the rise and fall of Chinese dynasties.

PATTERNS

The Chinese imperial state was structured to prevent the emergence of regional power centers that might successfully challenge the authority of the central government. Institutional details varied from dynasty to dynasty, but imperial statesmen were usually well aware of the danger posed by a “tail too big to be wagged.” During the heyday of the Tang dynasty in the early eighth century, for example, there was no regularly established level of administration between the approximately 350 prefectures and the center. The prefectures were grouped into ten province-size “circuits,” but these were provided with itinerant surveillance commissioners rather than real provincial governors. Commanders of local military units who mobilized troops without receiving permission from the capital might face the death penalty. Very similar arrangements for circuits of inspection and the control of troops had prevailed under the Han dynasty more than five hundred years earlier. Even after the emergence of the province as a regular unit of administration under the Ming and Qing dynasties, authority was quite deliberately fragmented. The Qing Green Standard and banner troops belonged to entirely separate structures, and within each province some units reported to the civil governor while others were under the authority of an independent military chain of command. Thanks to measures of this sort, Chinese dynasties were seldom threatened by powerful regional leaders emerging from their own administrative system, unless the exigencies of dealing with a major peasant rebellion had already necessitated a significant devolution of authority to provincial governors and regional military commanders.

The vast majority of the people of imperial China were farmers, and the rise and fall of the major dynasties was in most cases accompanied by agrarian unrest and rebellion. These peasant uprisings had various causes and contributing factors, including drought, floods, famine, pestilence, government exactions, and exploitation by corrupt officials and wealthy landowners.

The classic example of a revolt precipitated by natural disaster was that of the Red Eyebrows, who brought down the short-lived Xin dynasty of the usurper Wang Mang and created the conditions that made possible the restoration of the Han dynasty. Dikes along the silt-clogged Yellow River failed between 2 and 6 C.E., allowing the stream to flow southeastward into the Huai River. This resulted in the inundation of a vast swath of the North China plain and drove large numbers of people to seek refuge in the highlands of the Shandong peninsula. The regions affected by the flooding had been inhabited by some 28 million people, nearly half the population of the empire. The number of refugees far exceeded the ability of the government to provide relief, giving rise to famine. The starving people turned to roving banditry as their only hope of survival, and their small bandit groups eventually coalesced into the vast plundering horde of the Red Eyebrows.

Some six hundred years later, flooding in some of the same regions contributed to the downfall of the Sui dynasty as outlaw bands began to appear in the marshes and hill country along the lower course of the Yellow River. In the early 870s, the lands between the Yellow River and the Huai were afflicted by drought, floods, and plagues of locusts. The government was unable to relieve the resulting famine, which swelled the ranks of the bandit armies that were emerging as a major threat to Tang authority. The peasant uprisings against the Mongol Yuan dynasty that broke out in the 1350s were preceded by drought, famine, and the great Yellow River flood of 1344 that wrecked the irrigation system in the Huai valley. North China also experienced unusually harsh weather conditions for much of the two decades that preceded the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644; terrible droughts alternated with major floods and the occasional insect infestation, leading to widespread starvation and outbreaks of epidemic disease. It was reported that starving peasants flocked to join anti-Ming rebel groups by the tens of thousands.

Peasant uprisings in imperial China were typically preceded by natural disasters, but not every flood or drought led to rebellion. Agriculture in north China was heavily dependent on moisture-laden monsoon winds from the Pacific encountering cooler air currents from the heart of Asia at the right place and time to produce the needed amount of rainfall. If the currents failed to meet, there would be drought; if they met for too long, on the other hand, the result was likely to be excessive rainfall and flooding. These were fairly frequent occurrences, with China's dynastic histories noting 1,621 floods and 1,393 droughts over the space of 2,117 years.3 Given the ubiquity of such events, government policy must also have been an important factor determining whether adverse weather conditions would give rise to large-scale rebellion. When the imperial government was vigorous, distribution of relief grain and the prompt and effective use of military force could prevent serious outbreaks. When the effectiveness of government declined, however, relief grain was often unavailable and local officials were unable or unwilling to excuse peasants from their tax and corvée obligations. In the last years of the Ming dynasty, unpaid imperial troops helped to drive many peasants into revolt by requisitioning their crops. The most terrible episodes of flooding, moreover, can be blamed on a less effective government as much as on natural conditions, since they resulted from the failure of officially supervised water conservancy efforts on the Yellow River. Once the disaster had taken place, repair efforts could become an additonal irritant. The Yuan government's call-up of corvée labor to restore the Grand Canal and the Yellow River dikes in 1351, for example, drove many hard-pressed peasants to take refuge with rebel groups.

Government exactions and impositions could give rise to rebellions even in the absence of natural calamities. The great revolt against the Qin dynasty that began in 209 B.C.E. has traditionally been attributed to the heavy burden of labor service that the first emperor had imposed on his people, including the construction of roads, palaces, and the Great Wall. Although some modern scholars have questioned this received version, it is still undeniable that the first anti-Qin outbreaks occurred among groups of men assigned to forced labor or conscripted for military service on the frontier. Some eight hundred years later, the unreasonable demands of the state in the last years of the Sui dynasty converted what had been a controllable level of brigandage along the lower reaches of the Yellow River into a blaze of rebellion that threatened the survival of the regime. The specific cause in this instance was the obsession of the second Sui emperor with the military subjugation of the northern Korean state of Koguryo, which led him to conscript vast numbers of soldiers and porters from the farm population of areas near the Yellow River that had recently suffered from flooding. Many of these conscripts promptly deserted to swell the ranks of the bandit gangs in the hills and marshes, and the emperor's repeated failures on the Korean frontier encouraged the resisters and eventually persuaded government officials and members of the local elite in many regions of the empire to turn against him.

The popular response to natural disaster, famine, and other crises of survival took two basic forms, dubbed the “predatory” and the “protective” by modern scholars.4 The predatory mode was adopted by peasant communities that found themselves more or less destitute, and involved the formation of bandit gangs to roam the countryside and prey on those communities that were somewhat better off. Bandit groups often began small and then coalesced to form great bandit armies, such as the Red Eyebrows of Han times or the Nian rebels of the mid-nineteenth century, that swept across vast regions. In response to the predatory threat, the better-off communities organized themselves for self-defense. Leadership was normally assumed by local elites and landowners, whose kinsmen, tenants, and retainers would form the nucleus of a protective militia force. Such forces often abandoned their home communities to take refuge in more defensible terrain, building fortified encampments in hilly or mountainous areas. This was a very common response when barbarian invaders swept over most of north China in the early years of the fourth century, and quite similar behavior was seen in the same areas in the nineteenth century and even the first half of the twentieth century. In the unsettled conditions that followed the Japanese invasion, for example, the four hundred peasant households of Laowo, Henan, took refuge in a massive, earth-walled fort in 1938. The line between protector and predator was easily crossed when survival demanded it. Protectively oriented communities that found themselves deprived of their livelihood readily turned to banditry, just as they resisted excessive state exactions by turning to rebellion. As rebel movements grew in size, they often came to include both predatory and protective elements uneasily united in opposition to the rapacious demands of the state.

Even among the predatory forces, leadership was seldom in the hands of ordinary peasants. The typical leader of a large, semipermanent bandit gang in the nineteenth or early twentieth century was what one authority has called the “village aspirant,” a young man from a relatively well-to-do farm family with perhaps some literacy and ambitions of rising in the world. The ninth-century anti-Tang rebel leader Huang Chao, an unsuccessful candidate in the imperial civil service examination, fits this pattern remarkably well, as does the nineteenth-century Taiping leader Hong Xiuquan. There are also examples from various periods of leadership provided by men who had been local subofficials, military subalterns, or professional criminals such as salt smugglers. Liu Bang, one of the early rebel leaders against the Qin dynasty and the eventual founder of the Han, had been the leader of a unit of one thousand households. Two other early anti-Qin rebels were men of substance in their communities who had been placed in command of a unit of conscripts before they launched their rebellion. Among the leaders of the anti-Yuan rebels in the mid-fourteenth century were cloth merchants, salt smugglers, and Buddhist monks. Li Zicheng and Zhang Xianzhong, the two most important anti-Ming leaders in the 1630s and 1640s, were at least marginally literate and had probably seen some military service. Many of Li's followers were not peasants, but transport workers from the empire's network of post stations who had been let go by the cash-strapped Ming government.

In some periods, spiritual leaders and religious beliefs played an important role in mobilizing rebel forces. Although the anti-Qin rebels and the Red Eyebrows do not seem to have been animated by religious visions, the great Yellow Turban revolt against Han rule which erupted in 184 was led by the Daoist master Zhang Jue and his two brothers, who practiced faith healing and called for confession of sins. The religious element was less prominent in Sui and Tang, but reemerged several centuries later in Buddhist guise. The anti-Yuan rebellions in the 1350s were largely the work of White Lotus sectarians, who believed in the imminent arrival of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future. The White Lotus ideology would reappear in several unsuccessful revolts against the Qing dynasty in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Regardless of whether the framework and terminology was Buddhist or Daoist, these ideologies of rebellion shared a common millenarian outlook: The world was seen to be approaching a cosmic turning point when violence would sweep away the iniquitous old order and usher in a new golden age of peace and prosperity for the followers of the rebel movement. The mutant Christian ideology of the nineteenth-century Taiping rebels may be understood as a new variation on a very old theme.

Sectarian revolts inspired by “heterodox” ideas had great difficulty attracting support from members of the social and cultural elite, who were usually committed to a more rational Confucian outlook. As was the case during the Taiping Rebellion, they often inspired fierce resistance by Confucian-educated gentry and local elites. Other sorts of peasant rebels and bandits, however, could expect to gain some support from members of the elite if they managed to hold government forces at bay for an extended period of time and occupy towns and cities. Chen Sheng, the first to rebel against the Qin dynasty, was soon joined by learned men and ritualists who resented the government's harsh treatment of Confucian scholars. When bandit armies entered the Nanyang area of southwestern Henan some two hundred years later, many of the powerful landowning families there joined forces with them to bring down the usurper Wang Mang. Elite defection was also an element in the rebellions that ended the Sui and Ming dynasties. Opportunism was an important factor, but scholars who entered the rebel camp might also be moved by the belief that Heaven had transferred its mandate from the ruling house to the rebels, who badly needed to be instructed in court ritual and Confucian norms of government. The more ambitious of the rebel leaders, for their part, welcomed the administrative talent and the aura of respectability that the scholars provided. This mutual dependence of plebeian leaders and Confucian scholars helps to explain why successful rebels in imperial China replicated the pattern of the previous regime rather than moving in a truly revolutionary direction.

Widespread and moderately successful peasant rebellions could also inspire government officials, military commanders, and other members of the elite to launch their own independent risings against a faltering dynasty. The first revolts against Qin, led by the likes of Chen Sheng, were soon followed by the efforts of royal families and noble houses displaced by the Qin conquest to restore their ancient patrimonies. The great Yellow Turban rebellion against the Eastern Han dynasty in 184 was quickly put down, but not before it had provided the court's generals and governors with the opportunity to establish themselves as regional warlords who fought one another for dominance while paying little more than lip service to the authority of the emperor. The peasant rebellions against the Sui dynasty in the second decade of the seventh century encouraged many of the regime's own officers to revolt and carve out their own states in various parts of China; one of these opportunistic officials—Li Yuan, a relative of the last Sui emperor—succeeded in occupying the capital and establishing the Tang dynasty. As sectarian risings broke out against the Mongol Yuan dynasty in the 1350s, Yuan militia commanders such as Chen Youding in Fujian showed more interest in establishing their own regional regimes than in putting down the rebels. After the rebel armies of Li Zicheng entered the Ming capital of Beijing in 1644, most of the remaining Ming generals also began to behave as autonomous warlords.

During several of China's interludes of rebellion and civil war, such as the Sui-Tang interregnum and period of the anti-Mongol uprisings, the major contenders for power eventually led forces that were patchwork quilts of bandit gangs, landlord militias, and units of government troops that had surrendered or defected. These coalitions were led by men of various stripe, but almost always suffered from tensions between their plebeian and elite elements, their predatory and protective forces. A further source of instability was the loyalty of most of the fighting men to their own immediate unit commanders, whether former bandits or militia leaders, rather than to the man at the very top of the chain of command. Given these structural weaknesses, the defection of cities and military units was a fairly frequent occurrence in the civil wars of imperial China.

As the more capable and successful rebel leaders subdued their local rivals, often absorbing the defeated troops into their own political structures, the competing factions decreased in number and grew in size. A limited number of powerful regional hegemons emerged. In 620, for example, the newly founded Tang regime of Li Yuan held the Wei River valley and adjacent territories. To the east, the plains of Henan were dominated by a renegade Sui general named Wang Shichong. The plains north of the Yellow River (modern Hebei) were the realm of a former bandit chief named Dou Jiande. Another bandit leader, Du Fuwei, held sway between the Huai River and the Yangzi. The vast territories south of the Yangzi were in the hands of Xiao Xian, a scion of the the ruling house of the defunct southern dynasty of Liang. Two lesser leaders, formerly regimental-level officers in the Sui military, controlled most of today's province of Shanxi and the Ordos region within the great bend of the Yellow River. A similar balance of regional forces existed in the early 1360s, after the initial round of uprisings against the Yuan dynasty. The Yangzi valley was divided between the three powers of Wu (based at Suzhou), Ming (based at Nanjing), and Han (based at today's Wuhan). Five weaker regimes held Sichuan, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, and Yunnan, while semiautonomous Yuan militia commanders dominated the north. The formation of such regional states was characteristic of China's periods of rebellion and civil war.

Some of the regional leaders were essentially separatists whose principal concern was to preserve their independence for as long as possible. Others harbored the ambition of overcoming their rivals to reunify “all under Heaven” and establish a new imperial regime. These ambitious, expansionist leaders signalled their intentions and sought to gather support by taking imperial titles and assuming other trappings of legitimacy, instituting proper court ritual and appointing men to high offices. They competed with one another in several ways. One was the manipulation of symbolic propaganda, which in some periods might involve the discovery of numinous stones, purple clouds, and other auspicious portents. Another was to send envoys to persuade uncommitted local leaders to submit to their authority. The most important and effective means of competition, however, involved military force. The major contenders raised large armies and sought to conquer their opponents' territories. Campaigns usually centered around the capture of walled cities, administrative centers whose control ensured domination of the surrounding countryside, and battles in the open field were often precipitated by efforts to relieve besieged cities. Victory in a major battle could produce a decisive shift in the balance of power. The great Tang victory at Hulao near Luoyang in 621 eliminated both Wang Shichong and Dou Jiande and delivered the eastern plains to Li Yuan, just as Zhu Yuanzhang's victory in the Boyang Lake campaign of 1363 led to the annexation of the Han state on the middle Yangzi and a vast increase in Ming power. Chinese civil wars often exhibited a “band-wagoning” pattern, with subordinate elements of the defeated coalition and uncommitted local leaders rushing to align themselves with the winning side after a major battle. Participants seemed to expect the restoration of imperial unity, and local leaders without imperial ambitions of their own were more interested in ending up in the good graces of the eventual winner than in defending their independence to the last ditch.

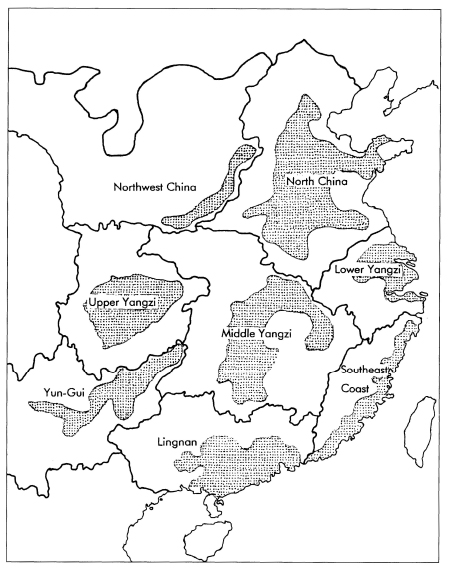

Map 3.1 China's physiographic macroregions according to G. William Skinner. Adapted by Don Graff based upon The City in Late Imperial China, G. William Skinner (ed.) (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1977), p. 214.

The shape of China's internal conflicts was also influenced by geography. The major rivers flowing from west to east, and particularly the mighty Yangzi, facilitated “horizontal” offensive operations, while “vertical” campaigns from north to south found the rivers to be obstacles rather than highways of conquest. China's many mountain ranges divided the country into discrete, easily defensible regions in which new dynasties could be incubated and autonomous regimes could hold out for decades. One such region is the Wei River valley of northwest China, the “land within the passes,” which gave rise to the Qin, Han, Sui, and Tang dynasties. Another is the territory corresponding to today's province of Shanxi, which sheltered the regime of the Shatuo Türks in the first half of the tenth century and the warlord Yan Xi-shan from 1911 to 1949. The greatest of all the regional bastions, however, is the mountain-ringed Sichuan basin on the upper Yangzi in the southwest. This was the last important territory to hold out against the Eastern Han founder Liu Xiu (Guangwudi) and the Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang, and it was also one of the last to fall to the Communists in 1949.

The boundaries of regional regimes often coincided with those of the eight “physiographic macroregions” into which the anthropologist G. William Skinner divided the territory of China proper. Each of these is a drainage basin largely bounded by hills or mountains. The peripheral areas of each macroregion are rugged and sparsely inhabited, while the major population centers are found in the river valleys and bottom lands of the regional “core,” where transportation is cheapest and agriculture most productive. In imperial times, Skinner noted, most of China's trade occurred within rather than between the various macroregions.5

The cellular structure of the empire surely influenced the pattern and outcome of China's civil wars. During a period of dynastic dissolution and chaos, competing regimes initially established themselves in different macroregions (or in important subdivisions of the same macroregion). Reunification required the consolidation of control over one's own region, followed by the invasion and subjugation of adjacent regions. If population, arable land, and other resources were more or less evenly distributed among the major contenders, expansion could be an arduous and drawn-out process. Once one of the contenders had managed to extend his control over several populous regions, however, he tended to aquire a momentum that enabled him to dispose of his remaining opponents relatively easily. Liu Xiu, for example, began his rise to power in 24 c.E. from a territorial base in the northern part of the North China plain. It took him six years to subdue his rivals on the plain and in the Shandong peninsula, but once he had, the autonomous governors of southern China fell into line with minimal resistance. Liu's last rival, Gongsun Shu in Sichuan, was not eliminated until 36, but the ultimate victory of his new Eastern Han dynasty was a foregone conclusion after 30. A similar pattern can be seen in the founding of the Ming dynasty more than a thousand years later. The balance of power in the Yangzi valley between the states of Han, Ming, and Wu was shattered by the Ming victory over Han in 1363. The annexation of the Han territories then provided the Ming leader Zhu Yuanzhang with the resources to guarantee the conquest of Wu in 1367. And with all of the Middle and Lower Yangzi macroregions in his hands, Zhu was able to overrun most of the rest of China in 1367-1368.

The civil wars that surrounded China's dynastic transitions rarely lasted more than fifteen years from the breakdown of the old imperial regime to the consolidation of its successor. (Unsuccessful rebellions, such as that of the Taipings in the nineteenth century, also tended to run their course within the same time frame.) The usual pattern saw one of the major contenders defeat his rivals one by one and add to the resources at his disposal until his ultimate victory was all but inevitable. On those relatively rare occasions when several of the weaker regional powers were able to cooperate effectively to check the expansion of their strongest competitor, however, military stalemate and political division could last for a very long time. In the last years of Eastern Han, Cao Cao succeeded in eliminating all of his rivals in north China, but his attempt to conquer the Yangzi valley and the far south was stymied when his two remaining opponents, Sun Quan and Liu Bei, joined forces to defeat him in the famous Battle of Red Cliff in 208 c.E. This battle ushered in the three-way balance of power between Cao's Wei state in the north, Liu's Shu-Han in Sichuan, and Sun's Wu state based on the lower Yangzi that dragged on until 263. The peasant rebellions against the waning Tang dynasty in the late ninth century also gave rise to a prolonged period of disunity, as the conflict between the Liang regime based on the Henan plains and the Shatuo Türk state in Shanxi (and later the incursions of the nomadic Kitan people from the northern steppe) permitted several autonomous regional regimes to cement their control over the south. Imperial unity was not restored until the second half of the tenth century, under the Song dynasty.

Even after a new imperial regime had defeated it major rivals and brought an end to the civil wars, its authority over the empire was usually far from complete. An important element contributing to the unifier's victory in the civil war was his willingness to make deals with potential opponents. Territorial governors appointed by the previous dynasty, fence-sitting local strongmen of various stripe, and the semiautonomous followers of other contenders for power were all won over with promises that they would be confirmed in office (or appointed to higher offices) and left in effective control of their own territories and armed forces. Care was usually taken to distinguish between major rivals with imperial pretensions and the lesser leaders who supported them; the former were marked for elimination, whereas the latter might be won over to one's own side by the right offer. The founders of the Tang dynasty created a large number of new units of local administration to accommodate de facto local power-holders within their state structure. They defeated the last serious armed challenge to their rule in 623, but it has been argued that several more decades passed before their government was able to extend its authority to the grassroots level and extract revenues from key areas of the North China plain.6 Dynastic founders were willing to trade local autonomy for nominal recognition of their authority because it spared them the trouble and expense of capturing every last county town and mountain fortress; it brought the violence and chaos of the civil wars more quickly to an end, and permitted the new emperor to get on with the work of reconstruction.

In many cases, dynastic founders thought it necessary or desirable to leave very large territories in the hands of their most powerful confederates. After he destroyed his great rival Xiang Yu in 202 B.C.E., the Han founder Liu Bang left his allies and generals in control of ten hereditary kingdoms which together accounted for well over half of the territory (and population) of the empire. Much the same approach was adopted by the Manchu founders of the Qing dynasty after 1644. They welcomed Ming generals who defected with their armies, and the most important of them were rewarded with large and virtually autonomus states, or “feudatories,” in the southern provinces of Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Yunnan. Such arrangements were, however, never more than interim solutions dictated by expediency. By 195 B.C.E. Liu Bang had squeezed out all but one of the original ten kings and replaced them with his own sons and brothers, and even these Liu family kings would be stripped of most of their power by the middle of the second century B.C.E. Once their realm was on a firm footing, the Manchu rulers in the seventeenth century also moved to rein in their overmighty subjects. An attempt to abolish the feudatories in 1673 provoked a major revolt that lasted until 1681, but this revolt ended in the complete defeat and elimination of the feudatories. New dynasties also worked to extend their authority at the local level, and eventually succeeded in replacing semiautonomous local strongmen with bureaucratic representatives of the center who were normally prohibited from holding office in their home areas. Local or regional autonomy was never a stable equilibrium state, but a stage in the process of reintegration leading to restoration of centralized imperial rule.

CHANGE OVER TIME

After this extended discussion of the recurrent patterns of imperial China's civil wars, it is well worth noting that no two periods of rebellion and disorder followed exactly the same pattern. Some saw heterodox religious sectarians playing a prominent role, while others did not. Some led quickly to reunification; others did not. In contrast to other periods of rebellion, the peasant risings against the Ming dynasty in the 1630s and early 1640s opened the door to the conquest of China by a non-Chinese people, the Manchus. Chinese culture was far from static over the more than two thousand years of the imperial era, and many periods had their own unique characteristics. During the “medieval” period from the fall of Eastern Han through the Tang, for example, pedigree and hereditary status counted far more than at other times, and the most viable and successful contenders for power were those who came from aristocratic families. This was in sharp contrast to the periods before and after, when humble men such as Liu Bang and Zhu Yuanzhang were able to fight their way to the imperial throne. The Ming dynasty was unique in the annals of imperial China because it conquered the north from a base in the Yangzi valley. All the other dynasties that ruled over a united China began in the north and then spread their control over the Yangzi valley and the far south. The Ming case was not a fluke, but the consequence of long-term demographic and economic shifts. For most of China's history, the most populous and economically developed parts of the country had been the North China plain and the Wei River valley. By the time of the Song dynasty, however, centuries of southward migration, land reclamation, and urbanization had finally tipped the balance in favor of the south. The next dynasty after the Ming, the Qing, came from the north, to be sure, but it was something of an anomalous case since it was established by foreign conquerors rather than domestic rebels. The first insurgent group to unify China after the imperial period, the nationalists of the Guomindang, pushed north from their original base in Guangdong during the Northern Expedition of 1926-1928 to establish nominal (if not actual) control over almost all of China proper.

It is also worth noting that many transfers of political power in imperial China were accomplished without peasant rebellions and civil wars. A number of dynasties came to power through palace coups or military revolts. This was the usual pattern for the regimes that held south China during the period of division between 317 and 589, and also for the “Five Dynasties” that dominated the north between 907 and 960. There were many anomalous cases. China's longest period of division was ushered in not by a peasant rebellion, but by a prolonged civil war among princes of the ruling Jin dynasty in the early years of the fourth century that created an opening for “barbarian” peoples, both within and beyond China's borders, to rebel against Jin authority and carve out their own kingdoms in the north. Another anamalous episode was the An Lushan rebellion, which broke out in 755 and nearly put an end to the Tang dynasty. It was launched by a Tang frontier commander who had been allowed to become too powerful, and his followers were professional soldiers rather than impoverished peasants. Although it was ultimately unsuccessful, the revolt left the Tang empire permanently divided. The fighting was brought to an end in 763 with a compromise solution that left several of the rebel generals in control of their armies and territories in return for their nominal acceptance of imperial authority. Some of these military provinces became virtually independent kingdoms, where leadership was passed from father to son and no taxes were paid to the Tang court, and even armies that had been loyal to the court during the rebellion began to emulate the ex-rebel provinces by choosing their own leaders and asserting local autonomy. This period of more than a century when autonomous provinces dominated by professional soldiers with a keen sense of economic and political self-interest paid little more than lip service to the imperial court—but made no effort to claim the throne for themselves—was unique in the annals of imperial China.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

The civil wars of imperial China are one of the better studied areas of Chinese military history, and there are a number of monographs in English dealing with particular dynastic transitions. One of the most important, and perhaps the most thorough of them all, is Hans Bielenstein's study of the overthrow of Wang Mang and the establishment of the Eastern Han dynasty. This was published in four installments in the Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities (BMFEA; Stockholm) over the space of twenty-five years, with the general title of The Restoration of the Han Dynasty.7 The volumes of greatest interest to the military historian are vol. 1, With Prolegomena on the History of the Hou Han Shu, in BMFEA 26 (1954), and vol. 2, The Civil War, in BMFEA 31 (1959). The second volume includes a substantial discussion of military tactics and techniques as well as a narrative history of the conflict. The end of Eastern Han is covered in Rafe de Crespigny, Generals of the South: The Foundation and Early History of the Three Kingdoms State of Wu (Canberra: Australian National University Faculty of Asian Studies, 1990), and the collapse of the Sui dynasty is treated in Woodbridge Bingham, The Founding of the T'ang Dynasty: The Fall of Sui and Rise of T'ang (Baltimore: Waverly Press, 1941). The principal works on the fall of the Tang dynasty and the Tang-Song interregnum are Wang Gungwu, The Structure of Power in North China during the Five Dynasties (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1963; reprint, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1967), and Robert M. Somers, “The End of the T'ang,” in The Cambridge History of China, vol. 3, Sui and T'ang China, 589-906, Part 1, ed. Denis Twitchett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 682-789. For the rebellions and civil wars that led to the establishment of the Ming dynasty, the best guide is Edward L. Dreyer, Early Ming China: A Political History, 1355-1435 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982). For the Ming-Qing transition, finally, there is the extremely thorough and detailed two-volume study, Frederic Wakeman Jr., The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1985). The many excellent studies of the great nineteenth-century rebellions and the warlord period in the early twentieth century are also relevant to this subject.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

Several of the works mentioned are already more than thirty years old, and all of them deal with military events within the conventional framework of political and institutional history. There is definitely room for new analyses of imperial China's internal conflicts that incorporate intellectual and religious history, social science perspectives, and the study of popular culture. It is also worth noting that even the basic outline of the civil wars and rebellions during the period of division from 317 to 589 has yet to receive serious attention from scholars writing in Western languages.

NOTES

1. Sima Qian, Shiji [Historical records] (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1959), ch. 3, pp. 105-106, 108. Also see Arthur F. Wright, “Sui Yang-ti: Personality and Stereotype,” in The Confucian Persuasion, ed. Arthur F. Wright (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1960), 47-76.

2. Arthur F. Wright, “On the Uses of Generalization in the Study of Chinese History,” in Generalization in the Writing of History, ed. Louis Gottschalk (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), 42.

3. Ray Huang, China: A Macro History (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1997), 25.

4. Elizabeth J. Perry, Rebels and Revolutionaries in North China, 1845-1945 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1980), 3-4.

5. G. William Skinner, “Regional Urbanization in Nineteenth-Century China,” in The City in Late Imperial China, ed. G. William Skinner (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1977), 211-217.

6. Robert M. Somers, “Time, Space, and Structure in the Consolidation of the T'ang Dynasty (A.D. 617-700),” Journal of Asian Studies 45 (1986): 971-994.

7. The Swedish title of this serial is Östasiatiska Museet Samlingarna.