Chapter 12

Editing, Evaluating, and Troubleshooting

When you use CAD programs, you typically create a part once but edit it many times. Design for change, also known as design intent, is at the core of most of the modeling work that you will do in SolidWorks.

This chapter starts with some very basic editing concepts, which you may already have picked up if you have been reading this book from the beginning. It also contains a summary of best practice techniques for modeling parts and a set of model evaluation tools that can help you evaluate parts. I placed these evaluation tools in a chapter devoted to editing because the create-evaluate-edit-evaluate cycle is one of the most familiar in modeling and design practice.

Using Rollback

Rolling back a model is one of the first and simplest things you will do when examining a model. It simply means using the Rollback bar to look at the results of the design tree up to a selected point in the model history. The order in which you create features is recorded, and if you change this order, you will get a different geometric result.

You can use several methods to put the model in this rolled-back state:

- Drag the Rollback bar with the cursor.

- Click the right mouse button (RMB) and select one of the Rollback options.

- Edit a feature other than the last one in the design tree. (SolidWorks rolls back the model automatically.)

- Choose Tools ➢ Options ➢ FeatureManager ➢ Arrow Key Navigation to control the Rollback bar with the arrow keys.

- Save the model while editing a feature or sketch and then exit the model. When the part is opened again, it is rolled back to the location of the sketch that was being edited.

- Press Esc during a long model rebuild. This method is supposed to roll you back to the last feature that was rebuilt when you pressed Esc. However, in practice, I have rarely seen it do this; it usually rebuilds the entire model.

- Select a face of the model, and from the pop-up menu, select the Rollback icon. The FeatureManager will roll back to the point in the feature list just before that feature was created.

- Select a face on the graphic area and select the Rollback icon. The model will roll back to just before the feature that created that face. This is a great technique for quickly rolling back before a specific fillet has been applied.

Using the Rollback Bar

The Rollback bar, which typically appears at the bottom of the FeatureManager in SolidWorks part documents, enables you to put the part into almost any state in the model history. Rollback is not the same as the Undo command; it's the equivalent of going back in time to change your actions at a particular point and then replaying everything that you did after that point. Figure 12.1 shows the Rollback bar in use. Notice how the cursor changes into a hand icon when you move it over the bar.

FIGURE 12.1 Using the Rollback bar

UNDERSTANDING CONSUMED FEATURES

When you use a sketch for a feature such as the Sketch Driven Pattern command, the sketch is left in the design tree, in the place where it was created. However, most of the other features—such as extrudes—consume the sketch, meaning that the sketch disappears from its natural order in the FeatureManager and appears indented under the feature that was created from it. Consumed sketches are sometimes also referred to as absorbed sketches.

To show features in their natural order instead of their consumed order, use the Show Flat Tree option (use Ctrl+T shortcut), accessed by right-clicking on the name of the part at the top of the FeatureManager, under the Tree Display selection, as shown in Figure 12.2.

FIGURE 12.2 Selecting the Show Flat Tree option

EXAMINING THE PARENT-CHILD RELATIONSHIP

In genealogical family tree diagrams, the parent-child relationship is represented with the parents at the top and the children branched below the parents. In SolidWorks, parent-child relationships are tracked differently. Figure 12.3 shows the difference between a genealogical family tree and the SolidWorks design tree.

FIGURE 12.3 Different interpretations of the structure of parent-child relationships

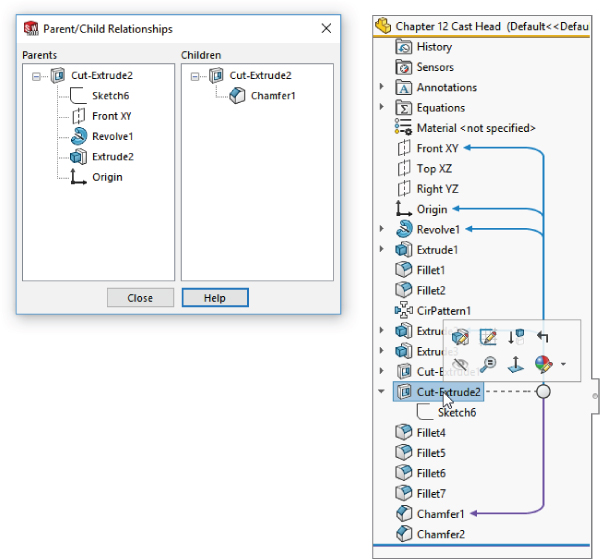

You can display the parent-child relationships between SolidWorks features, as shown in Figure 12.4, by right-clicking any feature and selecting Parent/Child. This helps you determine relationships before you make any edits or deletions, because you can see which features will be removed or go dangling (lose their references). Also, the Dynamic Reference Visualization (DRV) is helpful in showing both parent and child relationships (however, as shown in Figure 12.4, it does not indicate that Sketch6 is a parent of Cut-Extrude2). You can turn on the DRV through the menus at View ➢ User Interface ➢ Dynamic Reference Visualization.

FIGURE 12.4 SolidWorks Parent/Child Relationships panel and the Dynamic Reference Visualization

When SolidWorks puts the child feature at the top, it is, in effect, turning the relationship upside down. In the SolidWorks FeatureManager, the earliest point in history is at the top of the tree, but the children are listed before the parents. The SolidWorks method stresses the importance of solid features over other types of sketch or curve features.

For example, you create an extrude from a sketch, so the sketch exists before the extrude in the FeatureManager. However, SolidWorks places the sketch underneath the extrude. This restructuring can become more apparent when a sketch (for example, Sketch1) is created early in the part history and then not used to create a feature (for example, Extrude5) until much later. If you roll down the FeatureManager feature by feature, you arrive at a point at the end of the design tree where Extrude5 appears and Sketch1 suddenly moves from its location at the top of the tree to under Extrude5 at the bottom of the tree.

This scenario may cause a situation where many sketches and other features that are created between Sketch1 and Extrude5 are dependent on Sketch1, but where Sketch1 suddenly appears after all these other features. This can be difficult to understand, but it's key to effectively editing parts, especially parts that someone else created.

The main point here is that SolidWorks displays many relationships upside down. You need to understand how to navigate and manage these history-bound relationships.

To get around difficulties in understanding the chronological order of features when compared against the relationship order of features, roll back a model tree item by item or to work with the Flat Tree option.

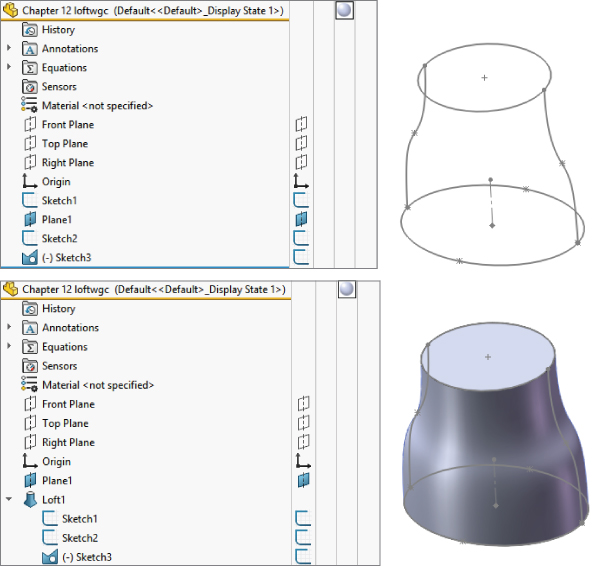

ROLLING BACK FEATURES WITH MULTIPLE PARENTS

Take an example such as a loft with guide curves. If you create the guide curves first, and then you create the loft profiles by referencing the guide curves, the loft automatically reorders these sketches when they display under the Loft feature such that the profiles are listed in the order in which they were selected, followed by the guide curves in the order in which they were selected. This is shown in Figure 12.5. This restructuring can be confusing if you want to go back and edit any of the relationships between the sketches. The order in which the sketches are displayed is not the order in which you created them. You can find this example in the downloaded files for this chapter under the filename Chapter 12 Loftwgc.sldprt.

FIGURE 12.5 Multiple parents and sketch reordering

Using Other Rollback Techniques

The Rollback tool is located on the RMB menu. Simply right-click a feature, and select either Rollback or Roll To Previous. If you are already rolled back and you right-click below the Rollback bar, you can access additional options to Roll Forward and Roll To End.

Editing any feature other than the last feature also serves to roll back the model while you are in Edit mode. As soon as you rebuild the feature or sketch, SolidWorks rebuilds the entire design tree.

The Tools ➢ Options ➢ View setting for Arrow Key Navigation enables you to use the up- and down-arrow keys to manipulate the Rollback bar. Under normal circumstances, the arrow keys control the view orientation, but after you have moved the Rollback bar once using the cursor, the up- and down-arrow keys control the Rollback bar. The left- and right-arrow keys have no effect on the Rollback bar.

Using Part Reviewer

Part Reviewer is a tool within SolidWorks that helps you examine the feature history of a part. You can find the Part Reviewer under Tools ➢ SolidWorks Applications ➢ Part Reviewer, or as one of the icons in the Task pane on the right side of the SolidWorks window, as shown in Figure 12.6.

FIGURE 12.6 Using the Part Reviewer

The controls at the top of the Part Reviewer window are, from left to right:

- Jump to Beginning: Roll back to the first feature.

- Step Back: Roll back one feature.

- Step Forward: Roll ahead one feature.

- Jump Forward: Unroll the entire tree.

- Show Sketch Details: When a feature is being examined, show the sketch and any dimensions as well.

- Show Only Feature With Comments: Only features to which comments have been added will be examined.

The small window under the controls is for the feature name that is currently under review. The pencil icon enables you to edit that feature, and the eye icon will hide the feature.

The large window under that is for comments. Comments can be added to each feature or sketch to help anyone who has to work on the part after you to understand anything that might need to be explained about the feature.

Reordering Features

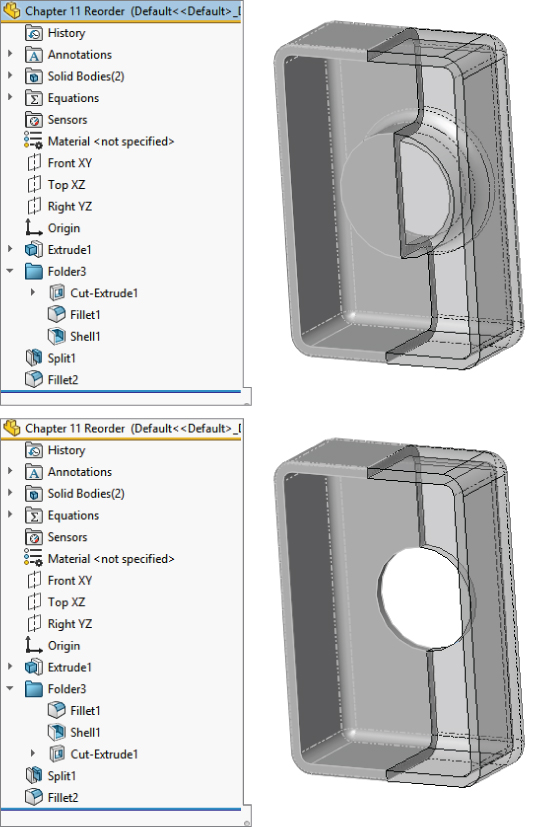

Feature order can make a big difference in the final shape of a part. For example, this order:

- Extrude

- Cut

- Fillet

- Shell

gives you a very different part from this order:

- Extrude

- Shell

- Cut

- Fillet

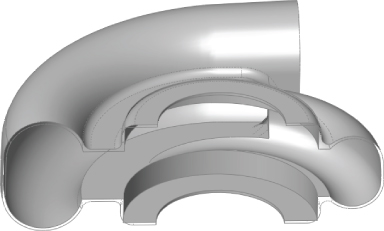

The results of these different orders are shown in Figure 12.7. (The part is split and partially transparent for demonstration purposes only.) You can view this part in the download material for this chapter, under the filename Chapter 12 Reorder.sldprt.

FIGURE 12.7 How feature order changes a part

On the part in the example shown in Figure 12.7, it is fairly simple to reorder the Shell feature by dragging it up the design tree. As a result, the well created by the Cut feature is not shelled around (to create a tube) if the cut comes after the shell. Also, notice the effect of applying the fillets after the shell rather than before it. The corners inside the box are sharp, while the outside corners have been filleted. When you apply the fillet before the shell, fillets that have a radius larger than the shell thickness are transferred to the inside of the shell.

When you are reordering the features, a symbol may appear on the reorder cursor that says that you cannot reorder the selected feature to the location you want. In this case, you may want to check the parent/child relationships to investigate. Sketch relationships, sketch planes, feature end conditions, and faces or edges selected for features such as shell, patterns, and mirror can cause relationships that prevent reordering. Also, remember that the Flat Tree display can be used to overcome some of these issues.

If two adjacent features are to swap places, it generally does not matter whether you move one feature up the design tree or move the other one down. However, there are isolated situations that are usually created by the nested, absorbed features discussed earlier, where one feature cannot go in one direction, but the other feature can go in the opposite direction, achieving the same result. If you run into a situation where you cannot reorder a feature in one direction even though it appears you should be able to, try moving another feature in the other direction.

Reordering Folders

There are times when, regardless of which features you choose to move and which direction you choose to move them in, you are faced with the task of moving many features. This can be time-consuming and tedious, not to mention having the potential to introduce errors. To simplify this process, you can put all the features to be moved into a single folder and then reorder the folder. Keep in mind that you cannot skip parent features, and you can reorder the folder only if each individual feature within the folder can be reordered.

To create a folder, right-click a feature, or a selected group of features, and select Add To New Folder. Folders should be renamed with a name that helps identify their contents. You can reorder folders in the same way as individual features. When you delete a folder, the contents are removed from the folder and put back into the main tree; the contents are not deleted.

You can add features to or remove features from the folders by dragging them in or out. If a folder is the last item in the FeatureManager, the next feature that is created is not put into the folder; you must place it in the folder manually.

The combination of the Flat Tree display and the Dynamic Reference Visualization can help you quickly answer many questions about parent/child relationships within a part.

Using the Flyout and Detachable FeatureManagers

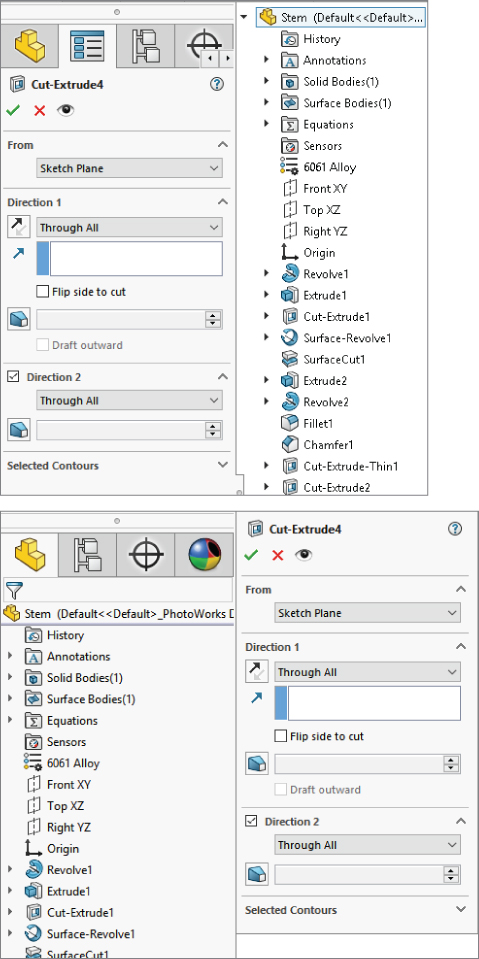

The flyout FeatureManager resides at the top-left corner of the graphics window and is automatically displayed if something like the PropertyManager covers over the space where the FeatureManager is usually displayed. The PropertyManager goes in the same space as the FeatureManager and is sometimes too big to allow this area to accommodate both managers in a split window. Figure 12.8 shows this arrangement.

FIGURE 12.8 The flyout FeatureManager and the PropertyManager

The flyout FeatureManager enables you to select items from the design tree when the regular FeatureManager is not available because it is covered by the PropertyManager. It usually appears collapsed, so that you can see only the name of the part and the part symbol. To expand it, click the plus icon next to the name of the part in the flyout FeatureManager.

You can use the flyout FeatureManager in parts or assemblies. However, you cannot use the flyout FeatureManager to suppress or roll back the tree.

You can access the settings for the flyout FeatureManager by choosing Tools ➢ Options ➢ FeatureManager ➢ Use Transparent Flyout FeatureManager In Parts/Assemblies.

You may prefer not to work with the flyout FeatureManager because it interrupts your workflow by covering the regular FeatureManager with a PropertyManager; this inhibits your access to items you may have to select from the FeatureManager, such as features and reference planes. If this is the case, you can use the detachable PropertyManager instead. Detaching the PropertyManager removes the need for the flyout. I often dock the detachable PropertyManager where the flyout FeatureManager would go or even use it undocked on a second monitor. The main advantage of using the detachable PropertyManager instead of the flyout FeatureManager is that with the detachable PropertyManager, you don't have to relocate features in the FeatureManager that were already in view.

Displaying the FeatureManager and PropertyManager

Figure 12.9 shows the difference between the flyout FeatureManager on the left and the detachable PropertyManager on the right. My preference is clearly the detachable PropertyManager. When you use the PropertyManager, you don't have to go hunting for features that are listed right in front of you when you do something that opens a PropertyManager. You can put the PropertyManager on a second monitor, in the graphics area, or outside the SolidWorks window. This works best on a wide-aspect monitor or multiple monitors.

FIGURE 12.9 Comparing the flyout FeatureManager with the detachable PropertyManager

You may ask, “What's the difference?” The difference is that when you do something like edit a sketch plane, the current state of the FeatureManager is covered and replaced by the PropertyManager. You may have had the new plane you wanted to use in view. Especially with long FeatureManagers, in both parts and assemblies, when the flyout appears, you have to again scroll to find the plane that was right in view. However, if you use the detachable PropertyManager, I think you will find it an improvement over the flyout.

To detach the PropertyManager, just display it by editing a feature, then pull the PropertyManager tab out of the FeatureManager area into the graphics window and release it. You can allow it to float or dock it with one of the available docking icons.

Following Selection Breadcrumbs

Selection Breadcrumbs is a tool that helps you see what you have selected. Any particular item may be characterized in many ways. For example, if you select a face, it is possible that you are selecting a top-level assembly, a subassembly, an individual part, a body, a feature, a face, and so on. The Selection Breadcrumb identifies exactly what is selected. It will display whether you have made a selection from the graphics window or the FeatureManager. If you have selected multiple items, the Selection Breadcrumb displays only the first item selected. It may display parents and children of the selected item, and the selected item is always highlighted in light blue within the breadcrumb. Breadcrumbs are displayed in the part document, but have more utility in assemblies where mates are involved. We will revisit breadcrumbs when we start working with assemblies in more depth.

The breadcrumb itself is displayed in the same area as the flyout FeatureManager, and is shown in Figure 12.10.

FIGURE 12.10 Selection Breadcrumbs show the detail of selection.

The display of Selection Breadcrumbs can be controlled at Tools ➢ Options ➢ Display ➢ Show Breadcrumbs On Selection.

Breadcrumbs not only show information; you can select individual breadcrumbs to make sure you have the proper level of entities selected. For example, if you have selected a face of a fillet, but you want to select the Fillet feature, first select the face. When the breadcrumb appears, you can select the feature name. Breadcrumbs also display child features, such as sketches or planes. Pressing the D key will move the display of the breadcrumbs to the location of the cursor.

Summarizing Part Modeling Best Practices

This section summarizes the best practices for modeling parts. Best practice lists are important because they lay the groundwork for using the software, which is helpful for new users and users who are trying to experiment with the limits of the software.

Only after you respect the rules and understand why they are so important will you know enough to break them. However, best practice lists should not be taken either too lightly nor too seriously. They are not inflexible rules, but conservative starting places; they are concepts that you can default to, but they can be broken if you have good reasons.

To a great extent, best practice rules are a function of CAD administration, but if you are a CAD user, you need to be aware of these suggested rules as implemented by the company for which you work. The purpose of best practices is to standardize procedures so that everyone at your company can work on the same models without needing to reinvent methods or guess how something was done. If all users at your company are CAD experts and never create models others can't edit, then you don't need best practices. If you have a mixture of users with high and low skill levels, then everybody needs to be trained up to a defined level and model according to your best practices. Best practices need to be defined most for the most difficult tasks. It can be tempting to try to define everything with best practices, but in the long run, you will find it more practical to limit your best practices to only what's necessary and make sure everything else is covered in training.

Following is a list of suggested best practices:

- Always use unique filenames for your parts. SolidWorks assemblies and drawings may pick up incorrect references if you use parts with identical names.

- Using Custom Properties is a great way to enter text-based information into your parts. Users can view this information from outside the file by using applications such as Windows Explorer, SolidWorks Explorer, eDrawings, and Product Data Management (PDM) applications.

- Learn to sketch using automatic relations.

- Use fully dimensioned sketches when possible. Splines are often impractical to fully dimension.

- Limit your use of the Fixed constraint.

- When possible, make relations to sketches or stable reference geometry, such as the origin or standard planes, instead of edges or faces. Sketches are far more stable than faces, edges, or model vertices, which change their internal ID at the slightest change and may disappear entirely with fillets, chamfers, split lines, and so on.

- Do not dimension to edges created by fillets or other cosmetic or temporary features.

- Apply names to features, sketches, and dimensions that help to make their functions clear.

- When possible, use feature fillets and feature patterns rather than sketch fillets and sketch patterns.

- Combine fillets into as few fillet features as possible; this also enables you to control fillets that need to be controlled separately—such as fillets to be removed for Finite Element Analysis (FEA), drawings, and simplified configurations—or added for rendering. The trade-off is that troubleshooting is more difficult with fillets that use more edges.

- Create a simplified configuration when building very complex parts or working with large assemblies.

- Model with symmetry in mind. Use feature patterns and mirroring when possible.

- Use link values or global variables or custom properties to control commonly used dimensions.

- Do not be afraid of configurations. Control them with design tables when you have more than a few configs, and document any custom programming or automated features in the spreadsheet for other users.

- Use display states when possible instead of configurations.

- Use multibody modeling for various techniques within parts; it is not intended as a means to create assemblies within a single part file.

- Cosmetic features—fillets, in particular—should be saved for the bottom of the design tree. It is also a good idea to put them all together into a folder.

- Use the Tools ➢ Options ➢ Performance ➢ Verification On Rebuild setting in combination with the Ctrl+Q command to check models periodically and before calling them “finished.” The more complex the model, or the more questionable some of the geometry or techniques might be, the more important it is to check the part.

- Always fix errors in your part as soon as you can. Errors increase the time it takes to rebuild, and if you wait until more errors exist, troubleshooting may become more difficult.

- Troubleshoot feature and sketch errors from the top of the tree down.

- Do not add unnecessary detail. For example, it is not important to actually model a knurled surface on a round steel part. This additional detail is difficult to model in SolidWorks, it slows down the rebuild speed of your part, and there is no advantage to actually having it modeled (unless you are using the model for rapid prototype or to machine a mold for a plastic part where knurling cannot be added as a secondary process). This is better accomplished by a drawing with a note. The same concept applies to thread, extruded text, very large patterns, and other features that introduce complex details.

- Do not rely heavily on niche features. For example, if you find yourself creating helices by using Flex/Twist or Wrap instead of Sweep, you may want to rethink your approach. In fact, if you find yourself creating lots of unnecessary helices, you may want to rethink this approach as well, unless there is a good reason for doing so.

- File size is not necessarily a measure of inefficiency.

- Be cautious about accepting advice or information from Internet forums. You can get both great and terrible advice from people you don't know, along with everything in between. Sometimes, even groups of people can be dead wrong. Get someone you trust to verify ideas, and as always, test your ideas on copied data to determine if they're effective.

If you're the CAD administrator for a group of users, you may want to incorporate some best practice tips into standard operating procedures for them. The more users that you manage, the more you need to standardize your system.

Using Design for Change

SolidWorks users have traditionally been taught to build each feature linearly, on top of the one that came previously. It turns out that this is not a great idea, especially as the parts become more complex. When each feature is dependent on the one before it, all the features must be solved in a particular order, and if one feature fails, so do all the features that come after it. This also slows down the rebuilding process.

Rather than using a linear daisy-chain modeling scenario, you should base features on entities that are less likely to fail or change in such a way that dependent downstream features also fail. In earlier chapters, I suggested that you make sketch relations to other sketches when possible instead of model edges for this very reason.

Keeping Track of References

The aim of these techniques is to help you organize the references between features in a part (and eventually in assemblies) such that you can make changes that you didn't plan on originally without breaking references, causing errors, and requiring a lot of model repair.

The underlying problem here is the dirty laundry that the history-based modeling paradigm has swept under the rug for decades: it doesn't handle changes in design intent very well. Experienced users are familiar with the scenario of making a seemingly simple change and seeing the FeatureManager light up with red Xs and exclamation marks (a lot of errors)—or trying to delete one little feature, and the software insists it must also take 15 other more important features with it.

In essence, you need to keep track of your references. If you sketch on a face, the feature that created the face becomes a reference. If a corner of your rectangle picks up an edge created by a fillet, then that fillet is part of the parent/child arrangement for the sketch. As your individual parts become more complex, the way these models react to change becomes more and more important because each change can potentially cost you more and more time. You will learn about the consequences of being too free with in-context relations in Chapter 20, “Modeling in Context”.

It's one thing to make models quickly the first time. Edits should take less time and not require a lot of rework. So how do you avoid this apocalyptic scenario with design for change?

Visualizing Horizontal Modeling

This better approach has been visualized in different ways. One technique calls it horizontal modeling or a “wide tree” approach, where instead of a long chain of features, you have a list of features all based on the initial planes and sketches such that there are only a couple of parents (and no grandparents). The rules for this type of modeling are such that no references to 3D geometry are allowed—only references to the stable reference geometry and initial sketches are allowed. To learn more about this technique, you can begin by reading Evan Yares's article on 3D CAD World:

Understanding Resilient Modeling

Another approach is called resilient modeling, where there is a specific method for different types of features. Features that require parents (such as non-sketch fillets or extruded text) come at the end of the tree. Resilient modeling was created by Richard Gebhard, and he has a set of training videos and other information at his web presence at:

Using Skeleton Sketches

What if a handful of sketch and plane features were used to centralize control of all the rest of the features? What if every feature, to the extent possible, related back to these “skeleton” features? Features such as fillets, shell, and draft by design require selections from solid geometry—but other features, such as any feature created from sketches, could be made with only reference to those original skeleton sketches and planes. The parent/child relationship would look very different for a model made in this way. Instead of looking like a long staircase, this tree would look more like a tree that gets wide very quickly. There would be fewer “generations,” but each generation would be more populated. The main upshot of this is that if any feature fails, the dependent features that fail should be minimized.

The first thing to notice is that errors in features at the top of the tree do not cascade down the tree as they do in the “stairstep” model. Second, it is always much easier to find how a model is constructed, because all the reference geometry used to build it is set up in the first few features. This scenario also has the potential to make better use of multithreaded processing because the logic is less linear and more parallel.

Proper design for change is a discipline that you need to make sure you follow with every model, every day. It is easy to get sloppy and take the easy way out, referencing model edges, sketching on 3D faces, but unless you are making very simple parts and get everything right the first time, this will come back to get you at some point.

Using Evaluation Techniques

You can use evaluation techniques to evaluate geometry errors, demonstrate the manufacturability of a given part, or to some degree quantify the aesthetic qualities of a given part or section of a part. I discuss evaluation techniques here because the design cycle involves iterations around the combination of create-evaluate-edit-evaluate functions. I discuss the following techniques in this section:

- Verification On Rebuild

- Check

- Zebra Stripes/RealView/Lights and Specularity

- Curvature Display

- Deviation Analysis

- Tangent Edges As Phantom

- Geometry Analysis

- Feature Statistics

- Curvature Comb

Many of these techniques apply specifically to plastic parts and complex shapes, but even if you do not become involved in these areas of design or modeling, these tools may help you to find answers on other types of models as well.

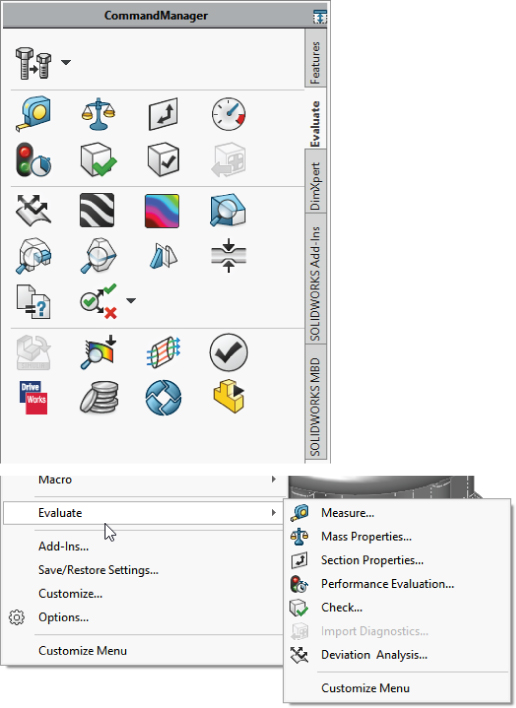

A special tab called Evaluate appears in the CommandManager; this tab has much of the functionality that is discussed in this chapter. Plus, the Tools menu has conveniently located several evaluation tools under the Evaluate option, as shown in Figure 12.11. You can use the commands on this tab to evaluate parts in several ways. Some focus on plastic parts or thin-walled parts or symmetric parts, and so on. Most of these tools are from the Tools toolbar and are also are found on the Evaluate tab in the CommandManager.

FIGURE 12.11 The Evaluate tab and the Tools ➢ Evaluate menu

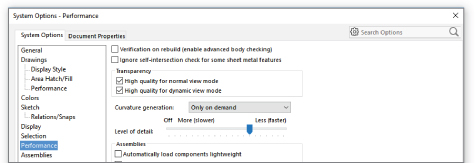

Using Verification On Rebuild

Verification On Rebuild is an option that you can access by choosing Tools ➢ Options ➢ Performance ➢ Verification On Rebuild. Under normal circumstances (with this setting turned off), SolidWorks checks each face to ensure that it does not overlap or intersect improperly with every adjacent face. Each face can have several neighbors. This option is shown in Figure 12.12.

FIGURE 12.12 The Verification On Rebuild option

With the setting selected, SolidWorks checks each face with every other face in the model. This is a better check than with the setting off, but it greatly increases the workload. The switch is deselected by default to prevent rebuild times from getting out of control. For most parts, the default setting is sufficient; however, when parts become complex, you may need to select the more advanced setting.

If you are having geometry or rebuild error problems with a part and cannot understand why, try turning on the Verification On Rebuild option and pressing Ctrl+Q. Ctrl+Q applies the Forced Rebuild command and rebuilds the entire design tree. Ctrl+B, or the Rebuild command, rebuilds only what SolidWorks determines needs to be rebuilt.

If you see additional errors in the design tree that were not there before, then the combination of Verification On Rebuild and Forced Rebuild has identified problem areas of the model, and the features that caused the errors failed. If not, then your problem may be elsewhere. You still need to fix any errors found this way.

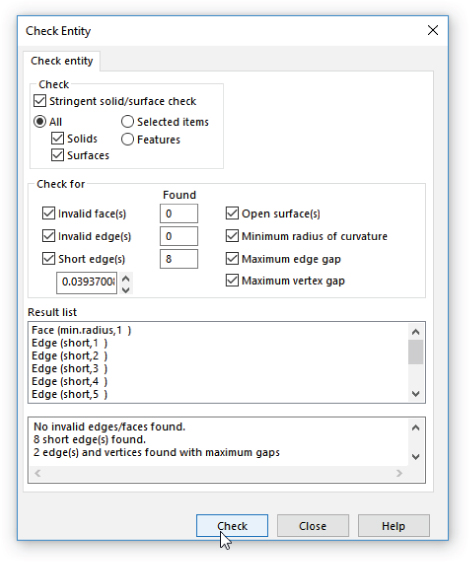

Using the Check Tool

Check is a tool that checks geometry for invalid faces and other similar geometry errors. It is also often used to find open edges of surface bodies, short edges, and the minimum radius on a face or entity. I usually apply the Check tool before selecting the Verification On Rebuild option. The Check tool points to the specific face or edge geometry (not features or sketches) that is the cause of the problem. When the Check tool finds general faults, the locations it points to may or may not have something obvious to do with a possible fix.

Check is a tool that checks geometry for invalid faces and other similar geometry errors. It is also often used to find open edges of surface bodies, short edges, and the minimum radius on a face or entity. I usually apply the Check tool before selecting the Verification On Rebuild option. The Check tool points to the specific face or edge geometry (not features or sketches) that is the cause of the problem. When the Check tool finds general faults, the locations it points to may or may not have something obvious to do with a possible fix.

Much of the time, the best tool for tracking down geometry errors is the combination of experience and intuition. It is not very scientific, but you will come to recognize where potential problems are likely to arise, such as those that occur when you attempt to intersect complex faces at complex edges, sharp or pointy geometry, and geometry or faces that vary significantly from rectangular with 90-degree corners. Figure 12.13 shows the Check Entity dialog box.

FIGURE 12.13 The Check Entity dialog box

Evaluating Geometry with Reflective Techniques

Evaluating complex shapes can be difficult. A subjective evaluation requires an eye for the type of work you are doing. An objective evaluation requires some sort of measurable criteria for determining a pass or fail, or a way for you to assign a score somewhere in the middle.

One way to subjectively evaluate complex surfaces, and in particular the transitions between surfaces around common edges, is to use reflective techniques. If you look at an automobile's fender, you can tell whether it has been dented or if a dent has been badly repaired by seeing how the light reflects off the surface. The same principle applies when evaluating solid or surface models. Bad transitions appear as a crease or an unwanted bulge or indentation. The goal is to turn off the edge display and not be able to identify where the edge is between surfaces for the transition to be as smooth as if the whole area were made from a single surface.

With all the RealView functionality in SolidWorks that emphasizes reflective finishes and backgrounds that emphasize the reflections, sometimes the RealView Appearances and Scenes are all you need to employ reflective evaluation techniques. Chapter 5, “Using Visualization Techniques,” covers all the display information you need to make the most of RealView Appearances and Scenes.

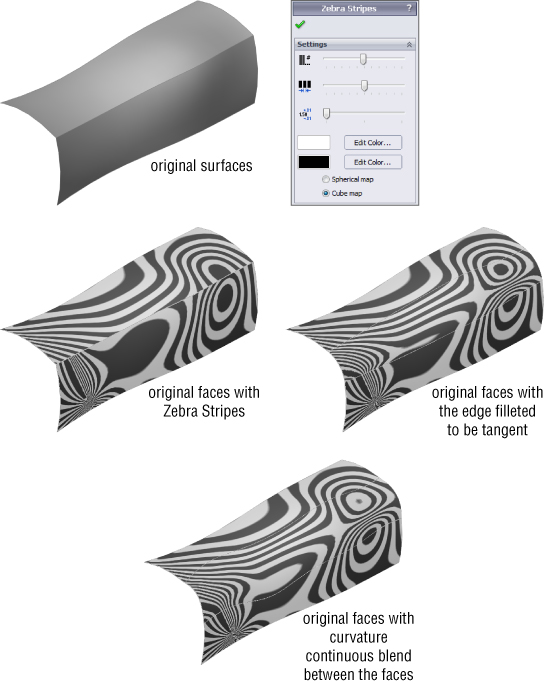

USING ZEBRA STRIPES

Zebra Stripes can be activated in three ways: by choosing View ➢ Display ➢ Zebra Stripes from the menus or by clicking a toolbar button on the View toolbar, or via the context/RMB menus. Zebra Stripes place the part in a room that is either spherical or cubic, where the walls are painted with alternating black and white stripes (although you can change the colors and the spacing of the stripes). The part is made to be perfectly reflective, and the way the stripes transition over edges tells you something about the qualities of the faces on either side of the edge. Four conditions are of particular interest:

Zebra Stripes can be activated in three ways: by choosing View ➢ Display ➢ Zebra Stripes from the menus or by clicking a toolbar button on the View toolbar, or via the context/RMB menus. Zebra Stripes place the part in a room that is either spherical or cubic, where the walls are painted with alternating black and white stripes (although you can change the colors and the spacing of the stripes). The part is made to be perfectly reflective, and the way the stripes transition over edges tells you something about the qualities of the faces on either side of the edge. Four conditions are of particular interest:

- c0 = Faces contact at edge

- c1 = Faces are tangent at edge

- c2 = Curvature of each face is equal at the edge and the transition is smooth

- c3 = Rate of change of curvature of each face is equal at the edge

The Zebra Stripes tool can only help you identify c0, c1, and c2, and only subjectively. This feature is of most value between complex faces. Figure 12.14 illustrates how the Zebra Stripes tool shows the differences between these three conditions.

FIGURE 12.14 Contact, tangency, and curvature continuity

Notice how, on the Contact-only model, the Zebra Stripe lines do not line up across the edge. On the Tangent example, the stripes line up across the edges, but the stripes themselves are not smooth. On the Curvature Continuous example, the stripes are smooth across the edges. The part shown in Figure 12.14 is a surface model and can be found in the download materials under the filename Chapter 12 Zebra Stripes.sldprt.

USING REALVIEW

The RealView Graphics display is available only to users with certain types of video cards. To see whether your card supports RealView, consult the system requirements on the SolidWorks website.

The RealView Graphics display is available only to users with certain types of video cards. To see whether your card supports RealView, consult the system requirements on the SolidWorks website.

RealView causes reflections that can be used in a way similar to the reflections in Zebra Stripes. Rotate the part slowly, and watch how the reflections flow across edges. Instead of black and white stripes, it uses the reflective background that is applied as part of the RealView Scene.

USING CURVATURE DISPLAY

Model curvature can be plotted onto the model face using colors, as shown in Figure 12.15. The accuracy of this display leaves a bit to be desired, but it does help you identify areas of very tight curvature on your part. Areas of tight curvature can cause features such as fillets and shells to fail.

Model curvature can be plotted onto the model face using colors, as shown in Figure 12.15. The accuracy of this display leaves a bit to be desired, but it does help you identify areas of very tight curvature on your part. Areas of tight curvature can cause features such as fillets and shells to fail.

FIGURE 12.15 Curvature display

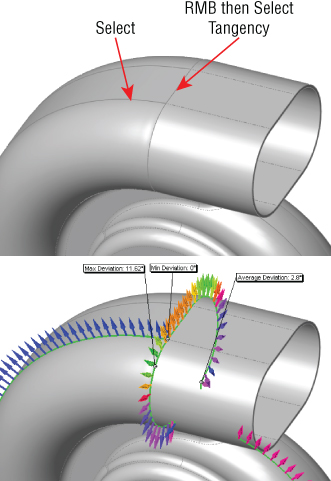

USING DEVIATION ANALYSIS

Deviation Analysis measures how far from tangent the surfaces on either side of a selected edge actually are. For example, the edges shown in Figure 12.16 are found to be fair, but not very good. I prefer deviations of less than 0.5 degrees. Often, with some of the advanced surface types such as Fill and Boundary, SolidWorks can achieve edges with less than 0.05 degree maximum deviation.

Deviation Analysis measures how far from tangent the surfaces on either side of a selected edge actually are. For example, the edges shown in Figure 12.16 are found to be fair, but not very good. I prefer deviations of less than 0.5 degrees. Often, with some of the advanced surface types such as Fill and Boundary, SolidWorks can achieve edges with less than 0.05 degree maximum deviation.

FIGURE 12.16 An example of Deviation Analysis

Although Deviation Analysis helps to quantitatively measure how close to tangent the faces on either side of the selected edge are, it doesn't tell you anything about curvature, so you must still run Zebra Stripes to get the complete picture of the flow between faces. Both tests must return good results to have an acceptable face transition.

USING THE TANGENT EDGES AS PHANTOM SETTING

Using the Tangent Edges As Phantom setting is an easy way to evaluate a large number of edges visually. This function does not do what the Zebra Stripes tool does, but it gives you a good indication of the tangency across a large number of edges very quickly. Again, it represents only tangency and tells you nothing about curvature continuity, nor does it give you as detailed information as the Deviation Analysis; it only tells you whether SolidWorks considers the faces to be tangent across the edge. Several releases ago, SolidWorks widened the tolerance of what it considers to be tangent, which is both good and bad news. It's good because features that require tangency will work more frequently, and it's bad because if fractional tangency degrees matter to you, “close” is not close enough. If you use Tangent Edges As Phantom as an analysis technique, you should follow it up with Deviation Analysis to find out how close you actually are.

I have never seen this function deliver false positives (edges displayed as tangent when in fact they were not), but I have seen many false negatives (edges that display as nontangent when in fact they were). Figure 12.17 shows a situation where the edges are displayed with solid edges, but Deviation Analysis shows them to have a zero-degree maximum deviation.

FIGURE 12.17 Using the Tangent Edges As Phantom setting

The measure of tangency has some tolerance. Users cannot control the tolerance, nor does the documentation say what it is. If SolidWorks says two faces are not tangent at an edge, you can believe that, but if SolidWorks says that the faces are tangent, you still have to ask how tangent. That is the question that Deviation Analysis can answer.

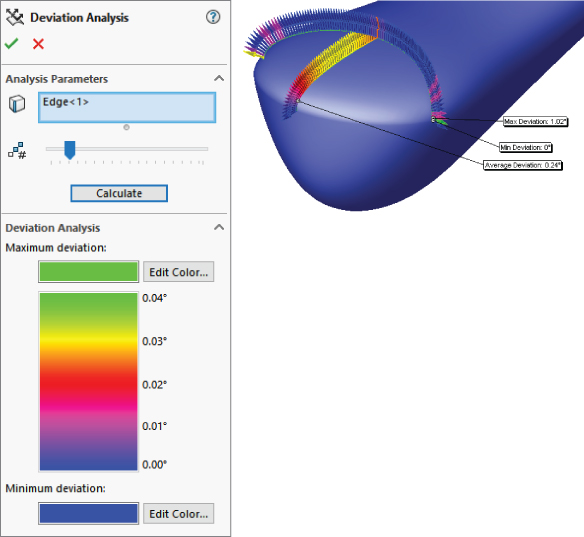

USING GEOMETRY ANALYSIS

Another tool that is fairly new is the Geometry Analysis tool. You can find it in the Tools menu or the new Evaluate tab in the CommandManager. It's an extremely useful tool for troubleshooting problematic geometry. The PropertyManager, shown in Figure 12.18, allows you to look for several specific items:

Another tool that is fairly new is the Geometry Analysis tool. You can find it in the Tools menu or the new Evaluate tab in the CommandManager. It's an extremely useful tool for troubleshooting problematic geometry. The PropertyManager, shown in Figure 12.18, allows you to look for several specific items:

- Short edges

- Small faces

- Sliver faces

- Knife edges/vertices

- Discontinuous faces or edges

FIGURE 12.18 Using Geometry Analysis to find typical problem spots

These specific types of geometry typically cause problems with other features, such as shells or fillets. If you are having difficulty with a feature failing for a reason that you can't explain, use the Geometry Analysis tool to point out potential problem spots. This is not a tool that will do your job for you, but it will give you useful information to help you do your job better with less guesswork.

The Geometry Analysis tool is available only with SolidWorks Professional and higher.

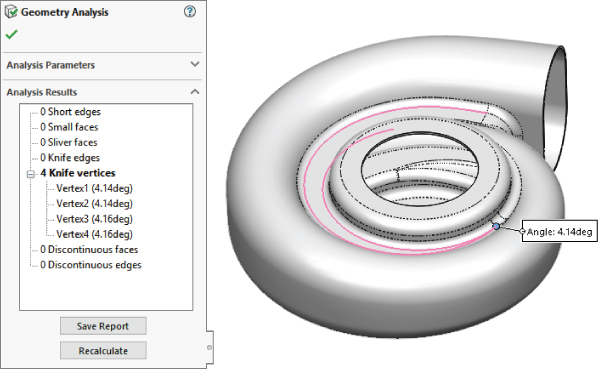

USING PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

The Performance Evaluation tool (formerly called Feature Statistics) has been used previously in this book to measure rebuild times for individual features in parts. You can find it either in the Tools menu or the Evaluate tab of the CommandManager.

The Performance Evaluation tool (formerly called Feature Statistics) has been used previously in this book to measure rebuild times for individual features in parts. You can find it either in the Tools menu or the Evaluate tab of the CommandManager.

Performance Evaluation lists the rebuild times of each individual feature in a part. This is useful for researching features, benchmarking hardware or versions of SolidWorks, and developing best practice recommendations for different tools and techniques. Figure 12.19 shows the Performance Evaluation interface.

FIGURE 12.19 Performance Evaluation helps you analyze rebuild times for features.

Overall, I don't recommend relying heavily on the data the Performance Evaluation tool provides, not because it's inaccurate, but because rebuild time is not always the best way to evaluate a model. You can certainly use the information, but you also need to keep it in perspective. A feature that takes a long time to rebuild but gives the correct result is always better than any feature that doesn't give the correct result, regardless of rebuild time.

USING THE CURVATURE COMB

The Curvature Comb is a graphical tool that you can apply to a spline, circle, arc, ellipse, or parabola to indicate the curvature along the length of the curve. You cannot apply a Curvature Comb to a straight line, because a straight line has no curvature. The height of the comb indicates the curvature. Curvature is defined as the inverse of radius (c = 1/r), so that as the radius gets smaller, the curvature gets bigger.

The Curvature Comb is a graphical tool that you can apply to a spline, circle, arc, ellipse, or parabola to indicate the curvature along the length of the curve. You cannot apply a Curvature Comb to a straight line, because a straight line has no curvature. The height of the comb indicates the curvature. Curvature is defined as the inverse of radius (c = 1/r), so that as the radius gets smaller, the curvature gets bigger.

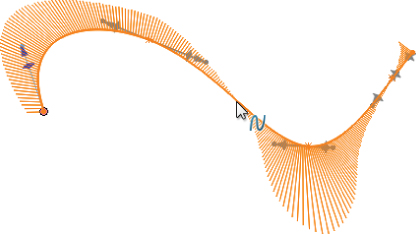

Figure 12.20 shows a Curvature Comb applied to a spline. Notice that the spline continuously changes curvature. An arc has constant curvature.

FIGURE 12.20 A Curvature Comb shows the constantly changing curvature of the spline.

When the comb crosses the spline, it means that the direction of curvature has changed (concave up to concave down, for example). When the comb intersects the spline, it means that the spline at that point has no curvature.

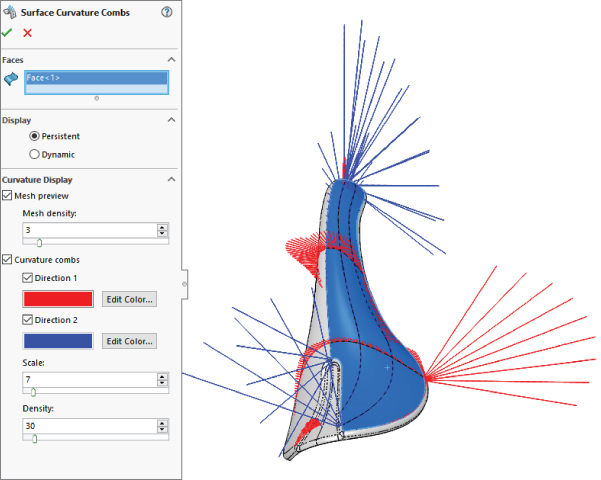

Surface Curvature Combs are also available from the RMB menu over a surface (although you may need to use the double-arrow expander at the bottom of the menu to see it). This helps you visualize the curvature along the UV curves of the face, as shown in Figure 12.21.

Surface Curvature Combs are also available from the RMB menu over a surface (although you may need to use the double-arrow expander at the bottom of the menu to see it). This helps you visualize the curvature along the UV curves of the face, as shown in Figure 12.21.

FIGURE 12.21 Surface Curvature Combs help you visualize curvature on curved faces.

Troubleshooting Errors

You will encounter many types of errors in SolidWorks. Improper installation and even bad computer hygiene can cause errors that might look like bugs in the software. Software bugs can cause errors that look like training issues. Operator errors can cause problems that are very difficult to sort out. I don't have the space in this book to go into all the possible errors and how to work around or fix them, but I will focus on feature-related errors that happen in the course of working on models.

When you get an error in SolidWorks, figuring out what caused the error and how to fix it is the goal of troubleshooting. Error messages appear in several places, including in message boxes in the graphics window, in the taskbar, in tooltip bubbles next to the PropertyManager, and in small symbols within the FeatureManager window.

Interpreting Rebuild Errors

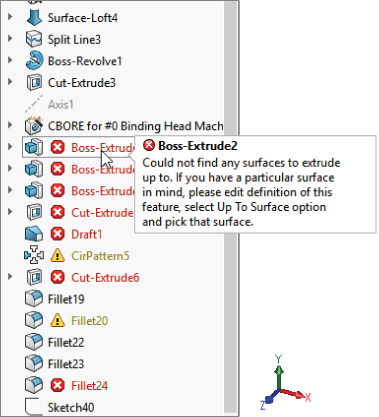

Chapter 3, “Working with Sketches and Reference Geometry,” discussed sketch colors and troubleshooting errors in sketches. You can apply much of what you learned from troubleshooting sketches to troubleshooting features in parts. The FeatureManager displays yellow triangles with black exclamation marks that point out some sort of warnings. A warning means there's a problem, but the feature hasn't failed. The red circle with an X in it is a failure symbol, and it means that the feature doesn't create any geometry.

Figure 12.22 shows a portion of a feature tree of a part from which a feature in the middle of the tree was deleted. Unless you are very careful about how you set up your part, a deletion of this kind will result in lots of errors.

FIGURE 12.22 Deleting a feature in the middle of a tree can cause many errors.

Notice the tooltip balloon in Figure 12.22. Many users get into the habit of clicking out of any sort of warning or error message. You shouldn't be afraid of errors. After you know how to deal with them, you will think of errors as a tool to help you investigate your model. The first thing you should do with an error message is read it. Eventually, you'll be able to recognize error messages and their meanings very quickly.

This error message says, “Could not find any surfaces to extrude up to… .” This means that you have lost the “top to surface” end condition on an Extrude feature. This is because the feature was deleted or possibly renamed in a Trim or Knit command. You may know the cause of errors, or you may not. If you inherited this part from someone who did not explain the state of the model to you, you might have to figure it out yourself. Most of the time, it's not difficult to figure out what's going on, especially with a little practice. If there's one thing I can guarantee you, it's that you are going to get a lot of practice evaluating errors.

When you inherit a model with errors, the first thing you should do is look for the error highest in the tree. Because of the nature of the history-based feature tree, errors always cascade down. When you make a change that causes errors, these errors will be lower in the tree than the change. Special situations can arise where a change causes an error up the tree, but they are rare. Again, the Flat Tree display and Dynamic Relationship Visualization should help you understand these situations.

Identifying Common Errors

Here are some common error messages and what they are really trying to tell you:

- Some Items are no longer in the model. You can reselect the items using the Edit Definition in the FeatureManager design tree. The first thing to know here is that Edit Definition has been gone for several releases now. The name of the command to look for is Edit Feature. You can get this message when an edge or a face for a selected feature no longer exists. A number of things can cause it, but the culprit is usually changed to the model upstream. As a result, if you roll back the model and make changes (especially if you delete something, but adding features can also cause errors of this sort), you can expect some problems when you unroll the model.

- Operation failed due to geometric condition. This is one that frustrates lots of users, because “geometric condition” is vague and could mean just about anything related to geometry. It can sometimes mean that a selection set is incomplete—the feature requires another face or another edge to be selected in order to work, or a fillet cannot work because an edge flips convexity, or a sketch line does not cut all the way across a solid body. There are too many possibilities to list, but this clue indicates that you need to check either the selections for the feature or the body on which the feature is operating. In more complex cases, it might mean that the part has some geometrical errors that you need to figure out by using the Check tool or Verification On Rebuild.

- Warning: This sketch contains dimensions or relations to model geometry which no longer exists. This is one of the better messages that SolidWorks provides. It is fairly self-explanatory and goes on to give you a couple of useful suggestions as to how you might fix the problem.

- Some filleted items are no longer in the model. Edit the feature to reselect the items. When all the edges selected in a Fillet feature are suddenly not there, the entire Fillet feature fails because there's nothing to do. This warning displays the red circle with the X in it. Some edges may remain selected, and the Fillet feature can still work. In these cases, you will get the next message, which is just a warning rather than an error.

- Warning: Edge for fillet/chamfer does not exist. In this case, you see the yellow triangle warning, and the fillet still creates some fillets, but one of the selected edges is missing, and the feature can't create all the fillets it created originally. The fastest way to fix this warning is to right-click it, select Edit Feature, and then immediately click the green checkmark icon. SolidWorks displays a message to make sure you want to just remove the references to the missing edge, but it continues to create fillets on the selected edges. Another option is to find the missing edge in the selection box and reselect an edge to take its place.

Many more types of errors exist, and rather than going through an exhaustive list, which would require another book of its own, I would like to impart to you some guidelines to help you find a useful answer. I hope you only have to figure out an error once, and you will remember it the next time you see it. Here are some general guidelines for troubleshooting errors with causes that aren't obvious:

- CAD doesn't like line-on-line geometry. In SolidWorks, you don't get extra points for being close. Most features require you to be exact. It is often a good idea to “overbuild” geometry so it's bigger than it needs to be if it's going to merge with other geometry.

- Zero thickness errors are difficult to diagnose. Zero thickness errors can be some of the most difficult errors for users who are new to 3D to diagnose. Much in the same way that CAD doesn't like line-on-line geometry, it doesn't like edges that create a section of a single body where there is air on two sides of an edge. If you were to extrude two rectangles that touch at a point, SolidWorks would create two separate bodies from that point, because it physically would fall apart if it were a single body. If the two touching rectangles were also trying to merge with an existing solid body, you would get an error.

- Planar means planar. If you click a face and it just won't let you open a sketch, maybe the face is not planar. Errors of this sort can happen in surfacing applications and imported geometry quite often. I use the Sketch icon as a quick test for whether a face is planar. SolidWorks doesn't really give you another way to measure this. Nonplanar faces can also cause lots of trouble with assembly mates.

- Even if it's planar, is it square to the coordinate system? If you work with plastic parts or castings, or anything else that requires draft, you can (and probably do) have faces that are not perpendicular or parallel to the standard reference planes. This can cause problems with projections and extrusion directions. For example, a circle projected at an angle becomes an ellipse, and an ellipse projected at an angle becomes a spline.

- If SolidWorks doesn't like one method, try another that produces similar results. One common example of this is when a constant radius fillet won't work, and you think it should work. In this case, try to use a variable radius fillet with all the same radius values.

For most errors, a rational reason exists. Belief in supernatural forces is not likely to be useful when troubleshooting errors in SolidWorks. If you're using very common features such as extrudes and cuts, and you run into errors, it's very unlikely that you've found a bug (although bugs in sketches are quite common). Generally speaking, the more traffic a feature sees, the less likely you are to find bugs with it. Sometimes, just determining whether the problem is with the software or with something you're doing is the toughest thing to troubleshoot. In general, users are far too eager to assign blame to the software.

Dismissing Errors

Some errors have the Don't Show This Again box. Don't get in the habit of checking that box unless you are very familiar with the cause of the error and how to fix it. Missing an existing error is much more costly than acknowledging redundant errors.

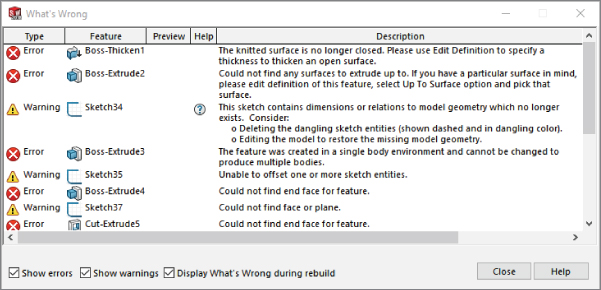

The What's Wrong box shown in Figure 12.23 gives you a list of the errors in the existing model. Some people find it embarrassing to be reminded about errors, especially if people have the habit of looking over your shoulder while you're working. Errors are in red; warnings are in yellow. The difference is between a feature that fails (red) and a feature that may just partially fail, such as a fillet that is missing a selected edge, but the rest of the edges have been filleted.

FIGURE 12.23 The What's Wrong box gives you a summary of all the errors and warnings in the current model.

The What's Wrong box can be turned off so it isn't displayed each time the model is rebuilt. You have this option with many of the error or warning messages. Each time a message is turned off in this way, it is added to a list of dismissed messages in System Options, shown in Figure 12.24. You may come up against a situation where you want to change how you respond to a repeating warning message. This box can fill up with a lot of messages, so think twice and make sure you understand the issue before you dismiss a warning message.

FIGURE 12.24 The list of dismissed messages is found in System Options.

Using SolidWorks RX and Performance Benchmark

SolidWorks provides a couple of automated troubleshooting tools: SolidWorks RX and Performance Benchmark. SolidWorks RX troubleshoots your system, or at least records facts about your system so someone trained in how to view the results can diagnose the problem.

USING SOLIDWORKS RX

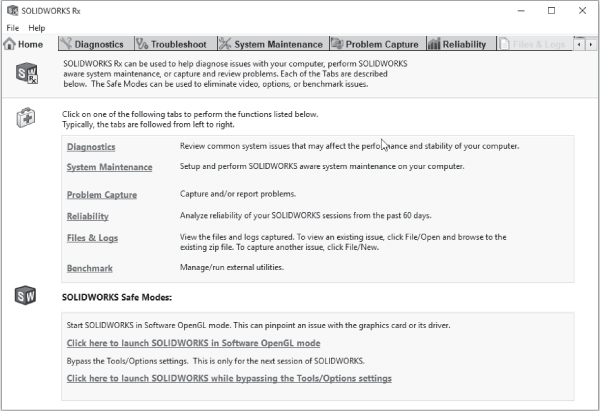

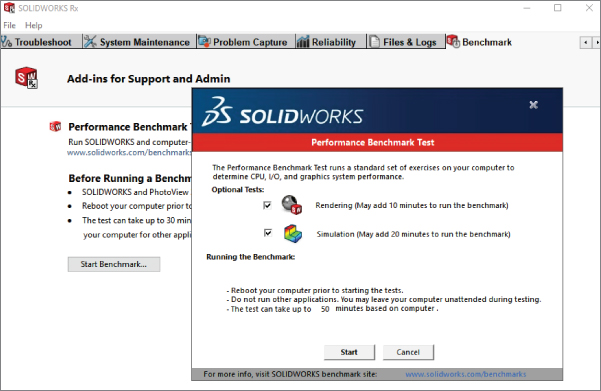

SolidWorks RX is a diagnostic tool that SolidWorks provides to help support techs solve your problem or to help you solve it yourself. You can access SolidWorks RX through the Windows Start menu ➢ All Programs ➢ SolidWorks 2018 ➢ SolidWorks 2018 Tools ➢ SolidWorks RX. Figure 12.25 shows the Home page of the interface.

FIGURE 12.25 Using SolidWorks RX

- Diagnostics Tab The first tab in the SolidWorks RX interface is a self-help diagnostics list, shown in Figure 12.26. This points out that my computer is compatible with my video card and that the driver is out of date (it gives me the option to download the correct driver); it also lists other information related to system maintenance.

FIGURE 12.26 Using the SolidWorks RX Diagnostics tab

The items in the Diagnostics tab are things that a support tech might ask you about if you were to call with a crash problem or some other problem that might be related to general system issues. Running SolidWorks RX before calling tech support could save you time and make you more self-reliant.

- Troubleshoot Tab The Troubleshoot tab contains mostly links to the SolidWorks Knowledge Base. (You'll need a subscription login.) These links are useful, and it is a good idea to check them out before calling tech support.

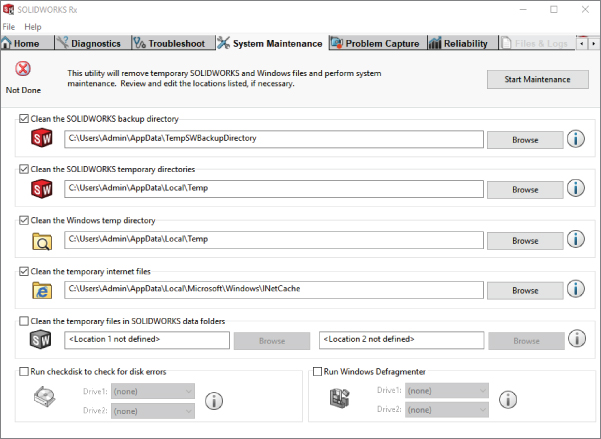

- System Maintenance Tab The System Maintenance tab contains paths to critical SolidWorks and system folders. If you click the Start Maintenance button in the upper-right corner, SolidWorks RX clears all the files from the listed paths. If you use the Browse buttons, you can clear paths individually. These are generally temporary and backup folders, so make sure you don't need any of the files before clearing them. Figure 12.27 shows the System Maintenance tab.

FIGURE 12.27 Clearing temp files with the System Maintenance tab

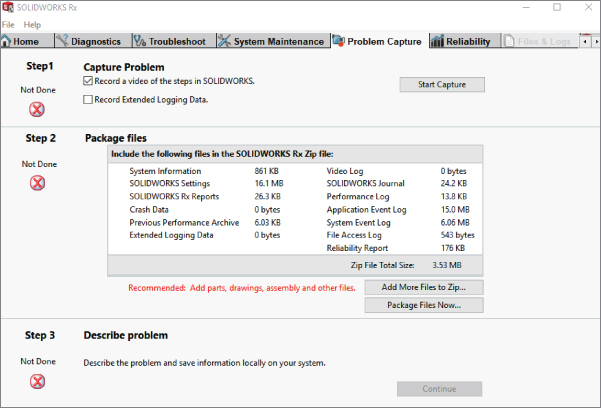

- Problem Capture Tab Often, when you call your reseller tech support asking for help with some sort of difficulty that isn't readily explained, the technician asks you to submit a SolidWorks RX log file. This log file includes the information from the other tabs, along with an optional description of the problem, SolidWorks files that were in use when the problem occurred, and a video of the problem actually happening. Figure 12.28 shows the Problem Capture tab.

FIGURE 12.28 Collecting information in the Problem Capture tab

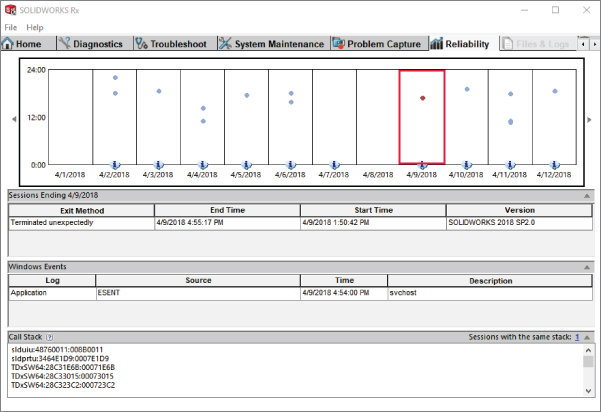

- Reliability Tab The Reliability tab in SolidWorks Rx shows a history of your SolidWorks sessions over the last two weeks. This history helps your tech support people and your CAD administrator see how much trouble you've been having with crashes (the red dots denote abnormal terminations). The Reliability tab is shown in Figure 12.29.

FIGURE 12.29 The Reliability tab gives you a record of sessions and crashes.

- Files & Logs Tab The Files & Logs tab shows a summary of the issue and a list of all the files included in the RX package. You can click the files that have been added to view their contents before sending the package. The Files & Logs tab is shown in Figure 12.30.

FIGURE 12.30 Listing the files to be sent in the RX package

USING PERFORMANCE BENCHMARK

SolidWorks RX has an Add-in tab that allows add-ins to be developed to extend the RX functionality. The Performance Benchmark runs your installation of SolidWorks through some automated display and rebuild exercises, and it measures the time for various operations such as zoom, rotate, and rebuild for a part and an assembly. Figure 12.31 shows the interface for the Performance Benchmark test.

FIGURE 12.31 Running Performance Benchmark

This benchmark is similar to the SPECapc benchmark, which can be used across several different CAD systems. SPECapc still exists (and is available at www.spec.org), and the SolidWorks specific portion of the benchmark was last updated in 2015. The point of benchmarks like this is to measure hardware capabilities.

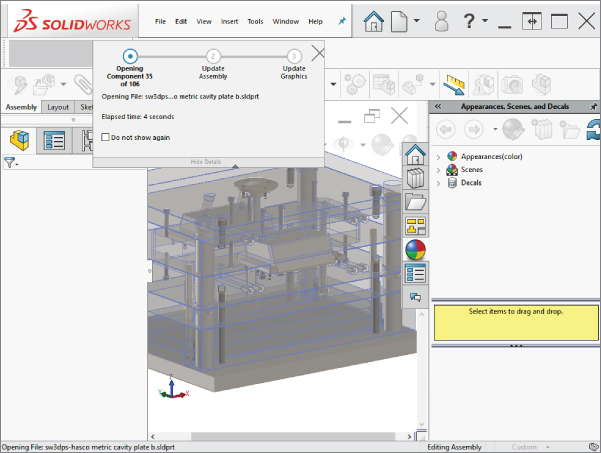

The models for the SolidWorks RX Performance Benchmark are a small, stamped part and an injection-mold die set. Figure 12.32 shows the benchmark in action.

FIGURE 12.32 Putting the computer through its paces with Performance Benchmark

You can also submit your results to the SolidWorks website, where they are posted immediately for comparison. This is used to help people make decisions about what hardware to buy.

You can check out the compared scores at www.solidworks.com/sw/support/shareyourscore.htm. Look through the list to see which kind of hardware receives a consistently high score and which is not represented in the top results.

You can find more information on benchmarking and SolidWorks at www.solidworks.com/sw/support/benchmarks.htm.

Tutorial: Utilizing Editing and Evaluation Techniques

In this tutorial, you will make some major edits to an existing part. You will use some simple Loft and Spline commands, and you will work with the rollback states and feature order, as well as some evaluation techniques. Follow these steps:

- Open the existing part with the filename

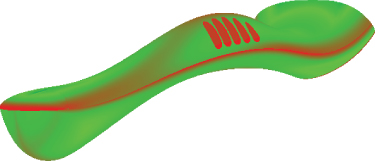

Chapter 12 Tutorial Start.sldprt. Roll the part back and step through it feature by feature to see how it was made. Edit the Loft feature to create it to help you understand how the part was built. Exit the Loft command, and move the Rollback bar back to the bottom of the tree. - Open the Deviation Analysis tool (Tools ➢ Evaluate ➢ Deviation Analysis). Select the edges, as shown in Figure 12.33. The maximum deviation is over 10 degrees, which is far too much. This part needs to be smoothed out, which you can do using splines in place of lines and arcs.

FIGURE 12.33 Deviation Analysis of an existing part

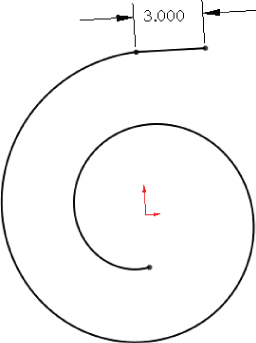

- The first step is to make the outlet all one piece with the spiral. You can do this with a fit spline. You need to create the fit spline before the loft profiles and after the spiral.

Expand the loft, and roll back between the Loft feature and the first sketch. Click OK in response to the prompt, and then roll back to just after the spiral, as shown in Figure 12.34. You could also use the Flat Tree view by right-clicking on the name of the part at the top of the tree, and selecting Tree Display ➢ Flat Tree View.

FIGURE 12.34 Rolling back to just after the loft

- Right-click the spiral in the FeatureManager and show it. Open a new sketch on the Top plane.

- Draw a tangent line from the outer end of the spiral. You will notice that you cannot reference the end of the spiral.

- Notice that you cannot select the spiral from the graphics window. Even when selected from the FeatureManager, it appears not to be selected in the graphics window. Ensure that it is selected in the FeatureManager, and then click the Convert Entities button on the Sketch toolbar.

- Draw a tangent line from the outer end of the spiral, and dimension it to be 3-inches long, as shown in Figure 12.35. This will be slightly angled up to the right.

FIGURE 12.35 Preparing for the fit spline

- Select both the converted spiral and the line, and select Tools ➢ Spline Tools ➢ Fit Spline. Set the Tolerance to .1 inch and make sure that only the Constrained option is selected. Click OK to accept the fit spline. Test to make sure that a single spline is created by moving your cursor over the sketch to see whether the whole length is highlighted. The goal is to make sure the Curvature Comb that automatically appears shows as smooth a transition as possible between the converted spiral and the straight line.

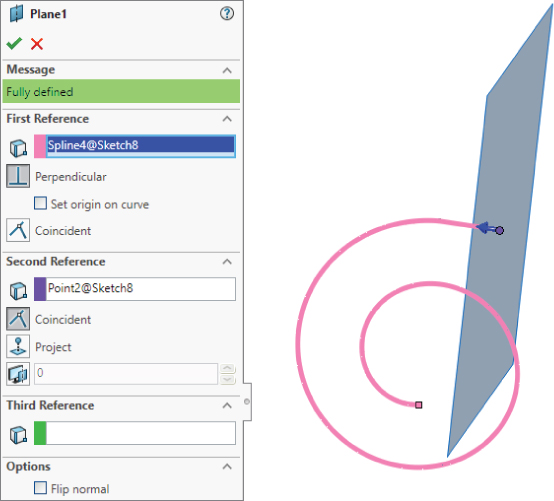

- Exit the sketch, and create a new plane. Choose Insert ➢ Reference Geometry ➢ Plane from the menus. Select the fit spline as the first reference and the outer end of the fit spline as the second reference. Click OK to accept the new plane. This is illustrated in Figure 12.36.

FIGURE 12.36 Creating a new plane

- Drag the Rollback bar down between Sketch3 and Loft1. If it goes beyond Loft1, then you need to navigate back to this position again.

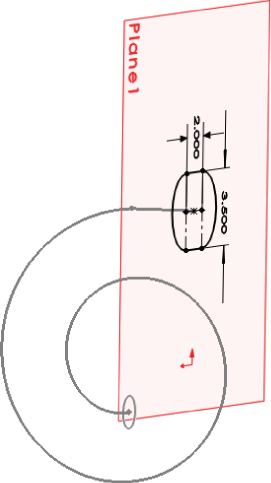

- Right-click Sketch3 and select Edit Sketch Plane. Select the newly created Plane1 from the flyout FeatureManager, and click OK to accept the change.

- Notice that the loft profile has moved to a place where it does not belong. This is because the sketch has a Pierce constraint to the spiral, and there are multiple places where the spiral pierces the sketch plane. Edit Sketch3, and delete the Pierce constraint on the sketch point in the middle of the construction line. Create a Coincident relation between the sketch point and the outer end of the fit spline, as shown in Figure 12.37 (most easily done by dragging the point in the sketch onto the point of the fit spline). Do not exit the sketch.

FIGURE 12.37 Sketch3 in its new location

- One of the goals of these edits is to smooth out the part. Remember that the Deviation Analysis tool told you that the edges created between the lines and arcs in Sketch3 were not very tangent. For this reason, it would be a good idea to replace the lines and arcs in Sketch3 with another fit spline.

Right-click one of the solid sketch entities in Sketch3, and click Select Chain.

- Create another fit spline using the same technique as in step 8. Again, keep an eye on the Curvature Comb to make sure the curvature around the connections between lines and arcs doesn't vary too much. Exit the sketch.

- Drag the Rollback bar down one feature so it's below the loft. Notice that the Loft feature has failed. If you hold the cursor over the Feature icon, the tool tip confirms this by displaying the message, “The Loft Feature Failed to Complete.”

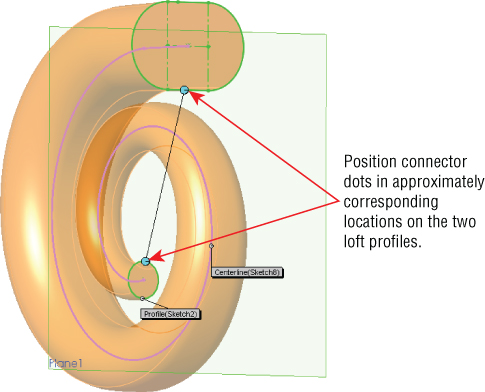

- Edit the Loft feature. Expand the Centerline Parameters panel if it isn't already expanded, and delete the spiral from the selection box. In its place, select the Spiral fit spline.

- If the loft does not preview, check to ensure that the Show Preview option is selected in the Options panel at the bottom.

- If it still doesn't preview, right-click in the graphics window and select Show All Connectors. Position the blue dots on the connector so it looks like Figure 12.38.

FIGURE 12.38 Positioning the connectors

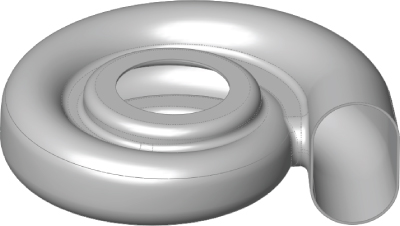

- Click OK to accept the loft. The loft should be much smoother now than it was before. To check this, right-click on the surface and select Surface Curvature Combs (remember you may have to expand the RMB menu). In addition, the Spiral feature should no longer be under the loft; it should now be the first item in the design tree. (If there are any irregularities in the loft, edit the Number Of Sections slider in the Centerline Parameters panel so the slider is in the middle instead of all the way to the right.)

- Drag the Rollback bar down to just before the Shell feature. Notice that Fillet5 has failed. Move the mouse cursor over Fillet5. The tool tip tells you that some references are missing. Edit Fillet5, and select edges in order to create fillets, as shown in Figure 12.39.

FIGURE 12.39 Repairing Fillet5

- Right-click in the design tree and select Roll To End. This causes the FeatureManager to become unrolled all the way to the end.

- The outlet of the involute is now longer than it should be. This is because the original extrude was never deleted from the end. Right-click the Extrude1 feature and select Parent/Child. The feature needs to be deleted, but you need to know what will be deleted with it.

- The Shell is listed as a child of the extrude because the end face of the extrude was chosen to be removed by the Shell. Edit the Shell feature, and remove the reference to the face. (A Shell feature with no faces to remove is still hollowed out.)

- Right-click Extrude1 and select Parent/Child again to verify that the Shell feature is no longer listed as a child.

- Delete Extrude1, and when the dialog box appears, press Alt+F to select Also Delete Absorbed Features.

- Edit the Shell feature, and select the large end of the loft. Exit the Shell feature. The results up to this step are shown in Figure 12.40.

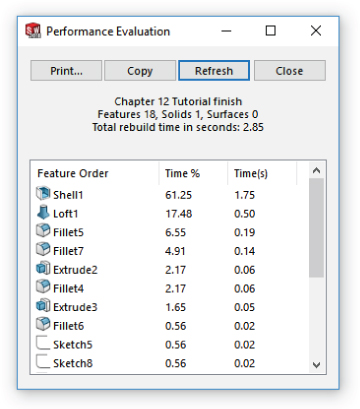

FIGURE 12.40 The results up to step 26

- Drag a window in the design tree to select the four Fillet features. Then right-click and select Add to New Folder. Rename the new folder Fillet Folder.

- Click the Section View tool, and create a section view using the Front plane.

- Reorder the Fillet folder to after the Shell feature.

- At this point, you should notice that something doesn't look right. This is because creating the fillets after the Shell causes the outside fillets to break through some of the inside corners. The fillets should have failed, but have not, as shown in Figure 12.41.

FIGURE 12.41 Fillets that should have failed

- Choose Tools ➢ Options ➢ Performance, and select Verification On Rebuild. Then click OK to exit the Performance menu, and press Ctrl+Q. The fillets should now fail.

- Click Undo to return the feature order to the way it was. Make sure to turn off the Verification On Rebuild option, because this unnecessarily slows down rebuild times.

- Save the part.

The Bottom Line

Working effectively with feature history, even in complex models, is a requirement for working with parts that others have created. When I get a part from someone else, I usually look first at the FeatureManager and roll it back if possible to get an idea of how the part was modeled. Looking at sketches, relations, feature order, symmetry, redundancy, sketch reuse, and so on are important steps in being able to repair or edit any part. Using modeling best practice techniques helps to ensure that when edits have to be done, they are easy to accomplish, even if they are done by someone who did not build the part.

Evaluation techniques are really the heart of editing, as you should not make too many changes without a basic evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the current model. SolidWorks provides a wide array of evaluation tools. Time spent learning how to use the tools and interpret the results is time well spent.

- Master It Set and test the following ease-of-use settings. Set and test the following settings to make sure you know where to find them and what they do:

- Arrow Key Navigation for the FeatureManager

- Flyout FeatureManager

- Selection Breadcrumbs

- Dynamic Reference Visualization

- Show Flat Tree

- Master It Use the part from the download material called

Horizontal.sldprt. This part uses several sketches to drive the entire part. Take a look through this part, and try to re-create one that is similar. - Master It Edit the previous part to see if you can make features fail. In particular, reorder some fillets. Next, try the same thing with the part called

Vertical.sldprt, which is provided with the download material. Examine the Vertical part and try to figure out why reordering the fillets causes so many failures.