While estimates of literacy rates vary widely, and cannot be established using current evidence, much recent work has concentrated on the role of literacy within Roman society (Bagnall 2011; Bowman and Woolf 1994; Corbier 2006; Cooley 2002; Harris 1989; Humphrey 1991; Pearce 2004; Tomlin 2011; Woolf 2000; 2009). Special attention has been paid to the relationship between literacy and power, in terms of ‘power over texts and power exercised by means of their use’ as well as by viewing writing as an enabling technology (Bowman and Woolf 1994, 6; cf. Pearce 2004, 44). Writing is also an embodied, physical practice associated with a particular range of objects. This is well illustrated by a 9th century source describing how ‘three fingers write, two eyes see, one tongue speaks, the whole body toils’ (Parkes 2008, 66). Literacy thus relates to the ‘big’ socio-cultural questions in Roman history, and to the question of the contribution of material culture studies to such debates.

This chapter examines one particular category of writing implement as a case study of contextualised and theoretically-informed finds analysis. Inkwells are cylindrical bronze containers with a central filling hole at the top, which can be secured by a small lid with a sliding lock mechanism. In terms of their cultural significance, inkwells stand for a process of writing that is otherwise dominated by organic materials that only survive under exceptional circumstances; these consist of papyrus or wooden leaf tablets and reed pens. Metal inkwells are rare enough to make an empire-wide survey possible: they have never been studied as a group but are published as individual finds even in older reports. I have compiled a substantial corpus of ca. 450 bronze inkwells gathered from dispersed publications. My current research project is concerned with understanding the practical use and symbolic significance of these objects, and how both relate to the people who wrote with them.

In both a forthcoming book and this chapter I explore the relationship between the material culture of literacy and ancient identities. There are well-known debates about the usefulness of the term ‘identity’, with some emphasising the sameness of a group and the power of identity politics, and others focusing on the fluid and constructed nature of identities (Brubaker and Cooper 2000; also Meskell 2001). With regards to Roman archaeology, Pitts (2007) argued that studies of identity have often become a continuation of the ‘Romanisation’ debate, focusing too heavily on cultural identity. However, as for other periods (e.g. Casella and Fowler 2004; Insoll 2007; Díaz-Andreu et al. 2005) Roman archaeologists are now producing nuanced studies that account for the multiple identities (e.g. in terms of ethnicity, gender, age, sexuality, class or caste, ideology and religion) of groups and individuals (e.g. Ferris 2012; Gardner 2007; 2011a; Hill 2001; Hodos 2010; Mattingly 2004; 2011; Eckardt 2014, 4–7).

The idea that the ‘consumption’and display of objects somehow directly reflects or expresses nebulously defined identities has been critiqued (e.g. Hicks 2010; Van Oyen 2013). It is clear that as archaeologists we have to pay close attention to the social and habitual practices of past agents within the structures and rules of a given society (e.g. Gardner 2004; Robb 2010) and to the relationships between people and between people and things (Latour 2005; Hodder 2012). Another key concept is the idea of material agency (e.g. Robb 2010, 504–5). Agency in this context is understood as the capacity to make a difference, where the intrinsic qualities of objects ‘condition how they can be made or acquired, used and exchanged, controlled and disposed of’ (Robb 2010, 497; cf. Gosden 2005; Versluys 2014, 14–18). In other words, we need to ask what pathways for action an object opens or closes. Objects are not mere passive reflections of people and societies but their use can challenge, change, and shape both. There seems to be an issue, however, over the methodology and practical application of these concepts to archaeological case studies (Fewster 2014). All too often, there is a regrettable absence of detailed engagement with the data; instead, single examples are used to stand for the wider argument.

In this chapter I present two case studies, dealing respectively with practice and representation. The first approaches the use of writing inkwells based loosely on a practice-theory framework and considers how inkwells may have shaped the habitual practices of those who used them. In the second case study I show that some aspects of the material culture of literacy can be studied through a representational reading of inkwells in funerary contexts, as long as these readings are nuanced. Depictions of writing equipment and of the act of writing can be viewed as performance, but it is important to take regional, chronological and gender differences into account. I contrast the ideological messages of tombstones depicting writing equipment with burial practices, focusing in particular on female graves. I do not argue simply that inkwells stand for ‘elites’ or women – but that they represent a particular skill, which had complex relationships to status, gender and other aspects of identity, and which played an important role in social practice. Overall, the chapter aims to understand what inkwells ‘did’ in Roman society, offering two brief case studies based on initial results of an ongoing research project.

Writing is a technology and the relationship between the cognitive activity of writing and its various tools is so habitual that it is often ignored. Haas’ (1996) research on writing practice shows that writing technologies affect thinking processes in subtle but measurable ways and the same is likely to be true for the Roman period. A good ancient example of the interplay of artefact design and the written ‘product’ is the observation by Quintilian (10.3.32) that the width of a wax tablet may affect the length of a student’s composition (Small 1997, 141–5). In general, technical ‘know-how’, understanding the modes of operation of any given object and technology, is a powerful form of cultural knowledge. Even the production of the ink itself required a range of ingredients and specific knowledge, as did the operation of the often intricate inkwell lids and of course the act of writing with a reed pen and ink. Previous research on the practice of writing has involved analysis of handwriting styles and posture (Austin 2010, section 9.1; Parássoglou 1979) and recent work examines wear on pens and how this relates to writing practices (Swift 2014, 203–5; 2017).

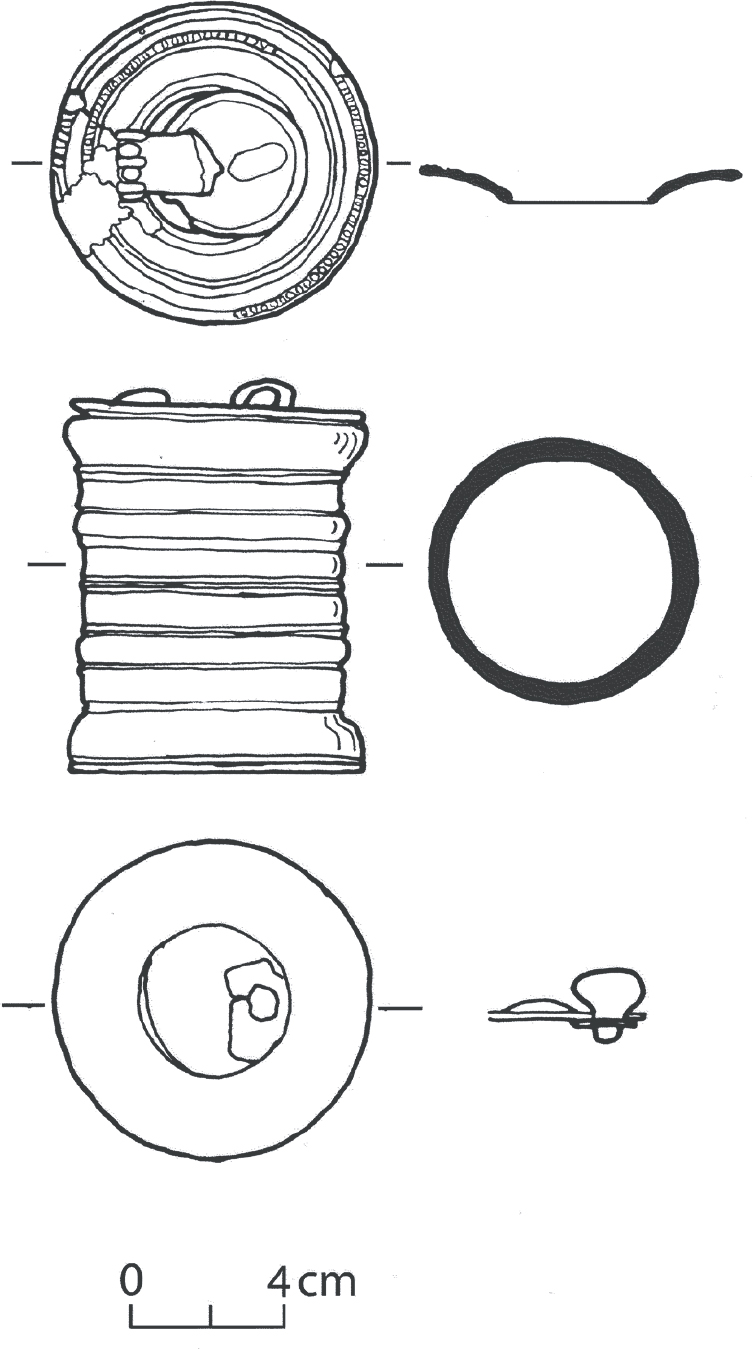

For this study I examine aspects of published inkwells that have not previously been studied, in particular size and volume. The size of an inkwell has obvious implications for the amounts of ink that could be used, and may give an insight into the practice of writing. Height and diameter measurements are not available for all recorded bronze inkwells, but here we can examine a distinctive inkwell type dated to the first century AD. Inkwells of Type Biebrich, named after the site in Germany where a well-preserved example was found, are characterised by being cast, and often possessing very elaborate lids; the type often occurs as a double inkwell (see Fig. 2.1; Božič 2001, a–b; cf. Fünfschilling 2012, 191). I currently have 48 examples in my database, of which 18 have both height and diameter measurements. The inkwells range in height from 34–53 mm and in diameter from 26–43 mm. There is normally no information on wall thickness, but it is possible to describe all these inkwells as of roughly cylindrical shape and calculate an estimated average volume of ca. 43 ml. There is a considerable range in sizes, with the largest inkwell possessing a volume four times greater than the smallest vessel.

How do these metal inkwells compare to glass and sigillata inkwells? Glass inkwells occur from the mid first to the early second century AD (Cool and Price 1995, 116–7) and are therefore roughly contemporary with Biebrich inkwells. Calculating volumes for glass inkwells is very much complicated by their usual fragmentary state. Moreover, the very function of this vessel form is still debated as they possibly contained valuable unguents rather than ink (Isings 1980, 288).

The use of sigillata inkwells (Ritterling 13) peaks in the first century AD, again making them roughly contemporary to inkwells of Type Biebrich. It has been noted that sigillata inkwells are larger than metal ones, perhaps indicating that the increased volume of ink was required by heavy users such as archivists and professional scribes (Božič and Feugère 2004, 36). Another suggestion is that sigillata ‘inkwells’ contained wax rather than ink (Fünfschilling 2012, 194) but it is difficult to envisage how wax would be removed from them. Willis (2005, 97) states that sigillata inkwells measure around 70 mm in height and 80–95 mm in diameter, although there are examples of up to 110 mm in diameter (G. Monteil, pers. comm.). A number of complete examples with measurements were considered (e.g. Genin 2007, pl. 45, no. 12; Brulet, Vilvorder and Delage 2010, 65, 187, 197; Fünfschilling 2012, pl. 9.254). Sigillata inkwells are not cylindrical, but if we treat them as such for the sake of argument, we arrive at an estimated average volume of ca. 330 ml. Sigillata inkwells are therefore indeed hugely larger than metal inkwells of Type Biebrich. More work is needed to explore how the size of metal inkwells may change over time, and what variation there is amongst the ceramic material.

In terms of overall practice, it is possible to make a number of suggestions based on a better understanding of inkwell volumes. Even 30 ml represents a considerable amount of ink, given that modern calligraphers typically use bottles of between 30–60 ml (e.g. Winsor and Newton, Parker, Waterman). Such a bottle of ink lasts a modern calligrapher a considerable amount of time, possibly a month writing five days a week (Cherrell Avery, pers. comm.). Ink also dried up, and of course inkwells would not normally be filled to the brim to avoid spillage and to facilitate dipping pens. This supports the suggestion that the larger inkwells were for group or professional use, although it is difficult to imagine how multiple scribes used a shared inkwell, which ideally is placed close to their side. Perhaps these large sigillata inkwells were for the storage of ink, which was then decanted into metal or organic containers?

Figure 2.1 Inkwell of Type Biebrich (after Bechert 1974, fig. 84.13).

Writing equipment, including inkwells, is frequently shown on tombstones and other funerary monuments, as well as on Campanian wall-paintings. The theca calamaria, the portable leather writing set that usually contained inkwells as well as pens and styli, is an important element in the self-representation of educated individuals, and these images are frequently reproduced to illustrate ancient writing practices. The question of why they were created is more rarely asked.

Bronze inkwells are depicted on Campanian wall paintings with other writing equipment such as styli, writing tablets, scrolls and wax spatula as well as coins (Meyer 2009). These so-called still-lifes of writing equipment are usually interpreted as references to negotium, ‘the sober, and, especially legal and financial, business of the family’ (Meyer 2009, 569). Meyer further argues that this aspect of writing is almost exclusively associated with men. By contrast, she interprets the figures of women holding a wax tablet in one hand and a stylus raised to the lips in contemplative fashion in the other hand as idealised and symbolic images of leisure and literary pursuits (otium). Meyer (2009, 589) argues that ‘The so-called female portraits instead have the pose and attributes of Muses, but if they attempt to depict ‘real’ women, they at best convey female aspirations to unreal qualities. Men could aspire to the literary life, but their companions – Muses or women portrayed as Muses – could only aspire to inspire it’. Is this an accurate assessment of female literacy?

Tombstones deliberately communicate aspects of identity, regardless of whether they are set up by (as occurs frequently in the Roman period) or for the deceased. The specific context is an opportunity to commemorate in visual form specific enacted identities (cf. Hales 2010). This self-fashioning of identities can be interpreted by archaeologists in terms of gender, status, and regionality. A striking feature of the tombstones depicting writing equipment and/or the act of writing is the overwhelming association with men in the many different parts of the empire where such images occur, notably Rome/Italy, Noricum and Phrygia but also Germany and Gaul (e.g. Diez 1953; Pfuhl and Möbius 1979, 542–4, no. 579 and no. 793; Schaltenbrandt Obrecht 2012, 32–3). There is only really one, often invoked but nevertheless unique, exception to this rule. This is a tombstone from Rome that depicts a butcher’s wife, who is seated in a high-backed chair and writing what are assumed to be the business accounts onto wax tablets (Zimmer 1982, 94–5, no. 2).

How does this compare to what we know about female literacy from other sources? Literacy levels amongst women are generally thought to have been below those of men and higher in the city of Rome and amongst provincial elite (Harris 1989, 259–72; cf. Laes and Strubbe 2014, 99). Such elite women could achieve very high levels of education, although such women’s perception in the male sources was complex (Hemelrijk 2004; Cribiore 2001, 74–101). Thus, on the one hand there was an emphasis on the ideals of ‘educated motherhood’ but on the other there was considerable prejudice against educated women, often accusing them of sexual licentiousness, ostentation and excessive masculinity (Hemelrijk 2004, 59–96). The education of girls may have ended earlier than that of boys, due to their younger age at marriage, but there is some evidence that women were trained for professions that involved literacy, such as teachers and scribes (Cribiore 2001, 78–83; Rawson 2003, 166–7; Haines-Eitzen 1998, 634–40; Treggiari 1976, 77–8). The survival of letters written by women in Vindolanda and Egypt has also changed perception of female literacy levels (Bagnall and Cribiore 2006; Bowman 2003).

What contribution can the study of graves containing inkwells and other writing equipment make to our understanding of female literacy? In particular, is there a possibility that the grave goods tell a different story than the ideological representations on tombstones and other visual media? A forthcoming book-length study of this material explores how the practices of reading and writing relate to the life course and how writing equipment shaped the ways the relationship between literacy, age and gender was expressed in graves (Eckardt forthcoming).

A preliminary survey of inkwells from graves suggests that women are proportionally much better represented than was thought from the literary sources and the tombstone evidence (see Fig. 2.2). My catalogue contains 125 graves with writing equipment, of which 45 were assigned to either men or women by the excavators. These graves come from across the Roman empire, and are dated from the first to fourth century AD, with concentrations in Italy, Switzerland, and Germany for the earlier and in Hungary for the later graves; 26 are thought to be male while 16 are thought to be female; there are also three burials of two or more individuals. There is of course a danger of circular arguments if grave goods are used to assign gender, as is often the case with older excavations. However, there are cases in which writing equipment was found in osteologically sexed female graves. One such example is known from Vindonissa (Switzerland), where Grave 98–1 is that of a woman aged ca. 18–25 buried with a three-year-old child. Amongst the finds were two scalpels, tweezers and an inkwell, leading to the suggestion that this is the burial of a female doctor (Hintermann 2000, 125–6; Hintermann 2012, 96, fig. XI.6; cf. Božič 2001a). Also found were glass and ceramic vessels, pig bones, and plentiful botanical remains as well as two coins dating the assemblage to the mid first century AD. Female doctors in the Roman world may have specialised in treating women’s diseases and childbirth, but also included surgeons and general physicians (Jackson 1988, 86–8; Künzl 2002, 92–9; Künzl and Engelmann 1997). Soranus (Gyn.1.3–4) sees literacy as an important skill for a good midwife, but that may not always have been the reality (Flemming 2007, 261).

Figure 2.2 Inkwells from the graves of men and women (total 48), where gender was ascribed on the basis of grave goods or osteological sexing.

Age is another important factor. There is little point in calculating overall proportions as an empire-wide survey by its very nature will only yield biased and incomplete data, but it is worth noting that Bilkei (1980) in his survey of Pannonian material records that three out of 70 inkwells come from children’s graves and in Switzerland of 21 graves with writing equipment two were those of children (Schaltenbrandt Obrecht 2012, 42–6). My forthcoming study of the burial data shows a significant number of children buried with inkwells, and this may include one case of a girl or young woman. This is an exceptionally rich, early first century AD grave found to the north of Rome, which contained two inkwells of Type Biebrich and an ivory writing tablet (Platz-Horster 1978, 184–95) as well as a set of miniature silver vessels, lamps, silver mirrors, crystal and alabaster cosmetic vessels and palettes, gold jewellery, beads and cameos, crystal, shell and amber objects, glass gaming pieces; these rich grave goods were originally probably placed into an ivory and another, larger wooden box. The grave was published as that of a young girl on the basis of the size of the ring, the presence of the miniature vessels and the amuletic objects but it is impossible to determine the exact age or sex of the remains, as no osteological data were published. Obviously future, more detailed, work will be carried out on inkwells from funerary contexts to further explore the relationship between their deposition, their use, and the people who were buried with them.

I have argued that good artefact analysis can be about both representation and practice. In some cases, in particular ‘ideological’ contexts such as tombstones and wall paintings, writing equipment is clearly used to indicate aspects of identity. These seem to relate to status: the erection of tombstones itself is not universal and in many cases the individuals depicted are junior officers, urban officials such as aediles and censors or professionals such as teachers and doctors. Such ancient self-identification can of course be contrasted with the views of others; thus from the perspective of elites in Rome any profession that involved tools and paid work was frowned upon (Purcell 2001). Provincial Roman burial assemblages have also been described as having an emblematic character; they are about fixing the deceased’s identity in certain ways and act as an expression of savoir-faire, about knowing the etiquette of consumption (Pearce 2015, 21). But that is only really the beginning of the answer to the question. It can be argued that inkwells in graves acted as symbolic representations of a skill, social practice, and important form of cultural knowledge. There are also significant regional differences; these relate both to the depiction of inkwells and to their typologies, although that would not necessarily have been obvious to people in the past.

An interesting variation between funerary representation and burial practice concerns the relationship between gender and writing equipment. Writing equipment appears to be proportionally better represented in female graves than it is on funerary and domestic monuments, perhaps suggesting a tension between the more ideologically charged public monuments and private practice. Of course, it has to be acknowledged that the sample of graves with inkwells is very small and it is therefore difficult to draw broader conclusions. Despite the limitations of the evidence, the case study demonstrates the potential tension between the representational role of inkwells in burials and that in paintings or tombstones. While the former might come closer to ancient practice, both are about skills of cultural distinction (cf. Pearce 2015).

The initial analysis of the practical properties of inkwells has raised more questions than it has answered, which must be a good thing. Close examination shows that inkwell use was not straightforward: ink had to be obtained and mixed with water, inkwells vary hugely in shape, decoration and size and not all appear to have been portable. There may be standardised sizes at certain times, even across different materials, but this needs to be explored in more detail. One of the features only really appreciated when handling ancient inkwells is how small some examples are, and that many forms have what can only be described as ‘fiddly’ closing mechanisms. These physical features would have resulted in differences in practice, with for example professional scribes preferring some forms over others.

My two case studies may appear to deal with practice and representation respectively, with the first about the ‘skill of writing’ remaining rather distinct from the second about ‘the skill of cultural distinction’. However, both case studies show that thinking about how people do things through artefacts is important if we hope to address big questions about Roman archaeology. One such question is literacy, a practice central to Roman power but also to economies, social customs, and professional know-how. Adopting a range of approaches must be the way forward, as is detailed and close engagement with the data, even if, as in this case, with preliminary data.

I would like to thank the organisers for a stimulating workshop, and Owen Humphreys for comments on an earlier draft. Gwladys Monteil and Joanna Bird kindly provided information on sigillata inkwells and Victoria Keitel helped with volume calculations. Cherrel Avery provided fascinating information from her practice as a calligrapher.

* Department of Archaeology, University of Reading.