In recent years, the excavation of new, so-called ‘soldier burials’ has revitalised interest in the topic of late Roman funerary practice. Fundamental to the identification of soldiers is the inclusion of grave goods that are thought to be linked to the Roman army and can be loosely labelled as military equipment: crossbow brooches; belt sets and accessories; and occasionally weapons. The frequency of this burial rite is lower in Britain than in mainland Europe, and while there is a general correlation between the burial practice and northeastern Gaul and the Rhine limes there is no strong frontier association for the practice in Britain. This discrepancy indicates that the practice requires further scrutiny. Of particular relevance to this volume, the objects in question may be considered doubly representational, specifically in the sense that crossbow brooches and belts are linked to the Roman army, and more generally in the presumption that grave goods should be directly associated with the identities of the deceased. Outright rejection of the representational role of military equipment is unhelpful, but uncritical acceptance that such objects identify soldiers is clearly problematic. To what extent can the practice be seen as truly indicative of the status and occupation of the deceased as Roman soldiers or officers?

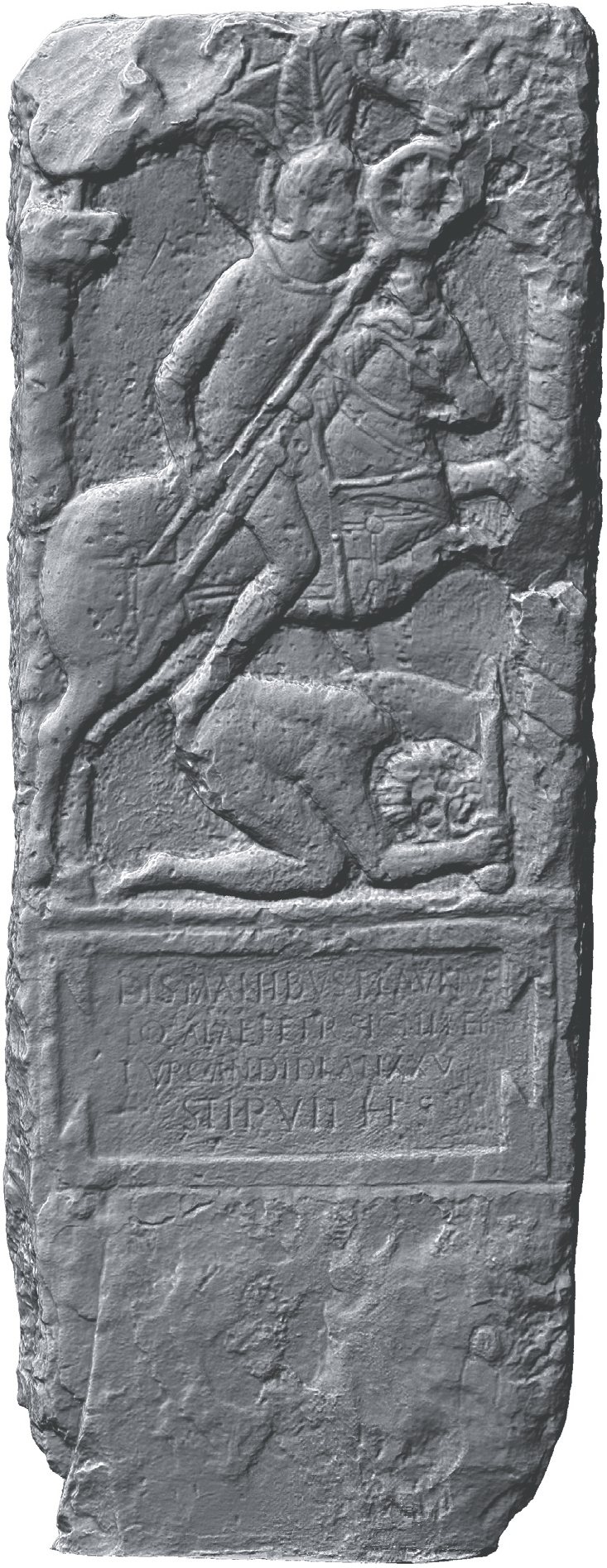

Traditionally, the Roman army can be identified in the archaeological record by the distinctive morphology of its architectural installations – towers, fortlets, camps, forts and fortresses etc. – and other highly visible material culture, including tombstones, building inscriptions, bronze diplomas, and arms and armour. Figural tombstones provide a good example of the representation of soldiers, employing both textual identification and visual cues (Fig. 3.1). Unfortunately, for most of the Roman West, the practice of inscription is extremely limited after the end of the third century AD. Soldiers are still depicted in other media, for example on mosaics as at Piazza Armerina or in statuary and sculpture as on the Arch of Constantine as well as in precious metal like the missiorum Theodosianus. Military bases continue to provide valuable information, but a particularly prominent source of information for late Roman military material culture are the furnished inhumations of the fourth century AD and after. Inhumation was a widespread burial practice throughout the Roman empire, but the inclusion of grave goods provides another layer of data. Not only do these graves provide useful examples of military equipment for traditional artefact research, they also serve as ‘evidence’ for a range of models pertinent to the understanding of the late Roman West – principally the incorporation of barbarians, ‘decline and fall’, and the expansion of Christianity. Artefacts are fundamental to the interpretation of this burial rite and its archaeological interpretation, and by extension the big picture of the late Roman West. As such, the ‘soldier burials’ of Britain provide a suitable case study to investigate how artefacts can provide answers to big historical questions.

Figure 3.1 A 3D scan of the tombstone of Flavinus, found in Hexham Abbey (RIB 1172). The iconography and text share Flavinus’ identity as a signifer (standard-bearer) of a Roman cavalry unit. © NU Digital Heritage, Newcastle University.

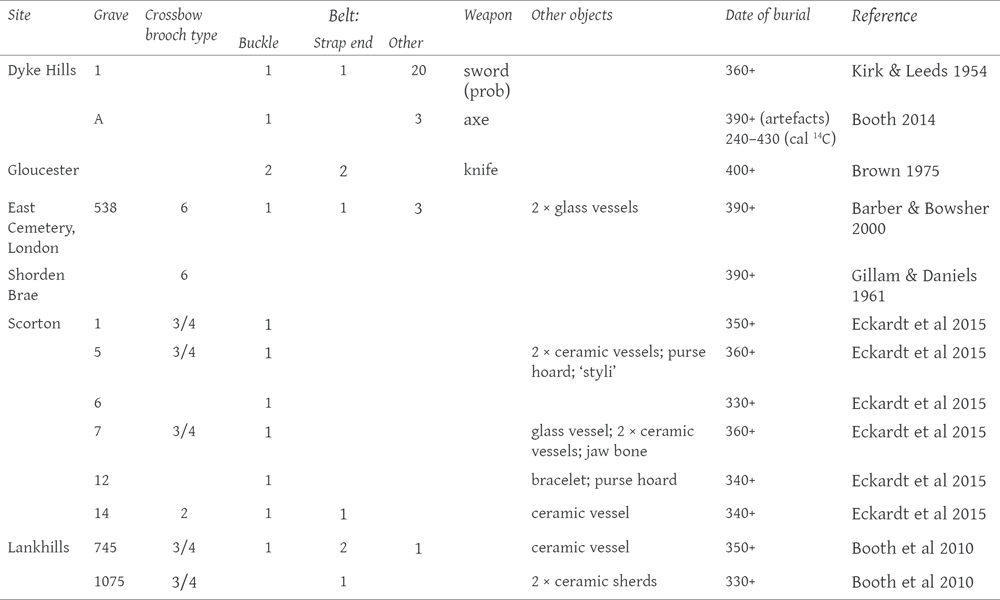

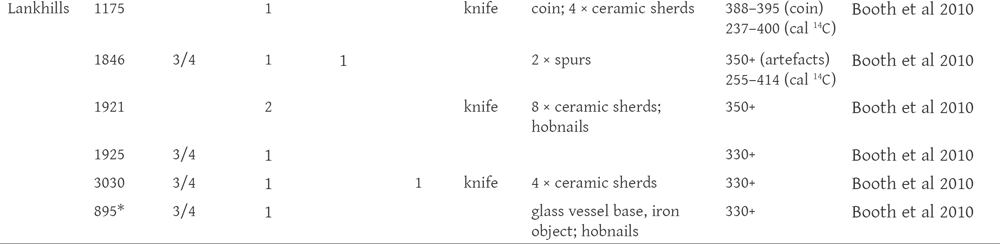

While it is unnecessary to enter into detailed typological description of the specific classes of artefacts considered in this paper, namely crossbow brooches and belt sets, it may benefit readers unfamiliar with these objects to provide a brief introduction. The crossbow brooch is a distinct form named for its visual similarity to a crossbow (see 514AC in Fig. 3.2); the shape and decoration of its principle elements on the head, bow, and foot are used to define its type and sub-types. Discoveries of crossbow brooches found in situ in graves confirm its depiction in art historical evidence, with the brooch used to fasten a cloak at the shoulder of its bearer. Belt sets are more complicated, consisting of a number of distinct components brought together for functional and decorative purposes in the form of the military belt – cingulum. In its most simple form, the leather belt consists only of a buckle, itself composed of a frame and pin (or tongue) and sometimes also a hinged plate that the frame and pin are attached to. The leather belt may also have a metal object fixed to the end opposite the buckle, known as a strap end. Other fittings can include mounts of various shapes (e.g. rectangular, propeller) and functions (e.g. suspension hooks or rings). A relatively simple belt can be seen in Fig. 3.2 which survives as a buckle (314AC, with frame, pin, and plate) and heart-shaped strap end (314AK); the belt set from Dorchester-on-Thames is a fine example of an elaborate belt with multiple components.

Figure 3.2 Grave 7 from Scorton, Catterick. An example of a soldier burial from fourth century Britain. © NAA and Sarah Lambert-Gates (University of Reading).

Two theoretical concepts have framed my understanding of the problems surrounding the representational role of artefacts in relation to ‘soldier burials’. The first concept is that of entanglement, or haecceities – ‘entities that consist of the bundled concretion of specific intersecting ‘lines’ of becoming’ (following Fowler 2013, 24–6; note also Barad 2007; Hodder 2012 is more specific in his definition). Applying this concept to ‘soldier burials’, the individual objects, their use within a grave, the archaeological recovery of the grave, the identification and interpretation of the objects and grave, and their inclusion into a research framework has created an entanglement of numerous discrete strands. These strands must be disentangled to create a new approach to the problem.

The second concept relates directly to the representational role of specific objects. Accepting that representational roles exist, how do we then allow for change or inconsistency in representation? Arguably, representation is accounted for in Latour’s (1999) concept of a reference, in which the chain of knowledge related to a particular entity forms the reference. Within society, circulating references reproduce a fixed representational function while accommodating localised variation (Fowler 2013, 30–5). In this fashion, a crossbow brooch can be understood as having a clear association with the Roman state or military, while the significance of particular forms, materials, or usage may impart different meanings to different people.

For the purposes of this paper, I define soldier burials as furnished inhumations containing objects associated with the army or warfare that allow the buried individual to be identified as a soldier or warrior. This definition is intentionally broad in order to critically consider the notion of a soldier burial and the roles of associated artefacts. It also accepts that the link between funerary assemblages and aspects of identity can seldom be proven outright (cf. Eckardt, this volume). While the specific type of object(s) and the chronology of practice vary across space and time, the ritual can be broadly said to manifest initially in furnished inhumations bearing crossbow brooches and/or belt equipment, as these objects were explicitly linked in ancient depictions and in modern scholarship with the Roman army (Swift 2000); graves may also include other objects, for example, weaponry or vessels made of metal, glass or pottery (Fig. 3.2). While traditionally perceived as a new burial rite that emerged outside the Roman tradition, the practice of furnishing graves with military equipment should be set within a longer and more geographically extensive tradition of furnished burial during the late Iron Age and Roman period (Haselgrove 1982).

The ‘soldier burials’ under consideration here are distinguished through a combination of artefacts linked to the Roman state and military, set within a period in which the Roman state is traditionally understood to be in decline. The inclusion of weaponry, however, adds further complications. The appearance of weapon-bearing graves of men alongside the furnished burials of women initially clustered in northern Gaul in the mid-fourth to early fifth century AD (Theuws 2009), and the subsequent development of sizeable row-grave cemeteries (including furnished and unfurnished inhumations) in the fifth–seventh centuries AD saw the distribution of this practice corresponding to the Roman frontier zones along the rivers Rhine and Danube (Brather 2005, 162–8). Graves bearing weapons and military dress accessories were first studied in the post-War era as a group in northern Gaul and the Rhineland, where coins from some graves clearly dated the practice to ca. AD 350–450, and the individuals buried were accepted as soldiers in the late Roman army. Initially these ‘soldier burials’ were thought to represent German laeti (Werner 1950), and subsequently and more widely as foederati serving in the army (Böhner 1963; Böhme 1974). The distinction between laeti – barbarian colonists settled inside the empire – and foederati – barbarians under treaty with the Romans outside the borders of the empire – is minor, but has significance for understanding the origins of the practice.

In summary, it was argued that location inside the Roman empire west of the Rhine and the presence of equipment identified the individuals as soldiers in the Roman army, but the practice of furnished inhumation had Germanic origins, supported by historic evidence for the settlement of Franks and Alamanni as reported in the Notitia Dignitatum and other textual sources. The fact that a similar burial custom could also be found outside the Roman empire east of the Rhine further validated the interpretation of barbarians serving in the Roman army who had returned ‘home’. The rite continued after the collapse of the Roman West in the fifth century AD, and served as a foundation for similar Frankish customs in the sixth and seventh centuries. While the men were generally interpreted as soldiers, it is also important to note the presence of furnished female burials in the same cemeteries, many of which contained tutulus brooches and other ‘non-Roman’ objects that reinforced ideas of barbarian origins. The discovery of furnished Anglo-Saxon graves dating to the fifth–seventh centuries AD in England further underscored the link between grave goods and Germanic origins, with the ethnic ascription of furnished graves supporting traditional historical narratives of the formation of the early medieval kingdoms.

Early in the debate, De Laet, Dhondt and Nenquin (1952) provided a detailed argument that the late Roman graves of northern Gaul and the Rhineland all shared a common material culture, and that Germanic foederati were archaeologically indistinguishable from Gallo-Romans. Shortly after, Hawkes and Dunning (1961) reinstated the association of the graves with men of barbarian origin, on the basis of evidence from the cemetery at Furfooz and the distribution of this material across the frontiers into barbaricum. Thus, inhumation with accompanying grave goods in the fourth-seventh centuries AD became intimately bound to notions of ethnicity. While the practice was understood as having barbarian or Germanic origins, it was accepted that the crossbow brooches and belt equipment were ‘Roman’, distinguishing the cultural origin of some grave goods from the ethnicity of the individual buried. Despite acute criticisms of such ethnic interpretations, furnished inhumations are still often accepted as archaeologically indicative of barbarian groups, either working for the Roman state or having some other relationship with it.

The ethnic reading of furnished inhumations has been critiqued by a number of scholars. Halsall (1992) demonstrated that many aspects of the ritual had no precedents in the traditional Germanic territories east of the Rhine, questioned the supposed Germanic origins of some of the objects included in the graves (e.g. tutulus brooches), and pointed out the uneven distribution of the graves. For Halsall, the graves are indicative of competition among local elites in the absence of effective Roman imperial control, with the burial ritual making statements of prestige and power through the use of symbols – brooches and belt sets, weapons – normally reserved for officials of the empire (Halsall 2000). In this model, the representational roles of these objects were embraced and exploited in the burial ritual for local, presumably familial benefit. Theuws (2009) concurred with Halsall’s critiques, but offered a different interpretation, advocating a case for the burial practices as rhetorical communication of the political and ideological agendas of the burying group. Read as ritualised rhetoric, Theuws (1999; 2009) interpreted the furnished burials, particularly the ‘weapon’ burials of the late fourth-early fifth century AD, as a new ritual in which the burying community was making claims to ownership and control of land, perhaps even creating an ancestor, through display of symbolically loaded material culture. The inclusion of brooches and belts in some of these burials, Theuws (2009, 311–2) hypothesised, may be due to the presence of veterans in groups claiming the lands, or possibly the assistance of imperial authorities. Regardless of the interpretation that one may favour, both Halsall and Theuws highlight the continuing representational significance of crossbow brooches and belt equipment.

From this overview, it should be clear that late Roman furnished inhumations are examples par excellence of an entanglement (Fowler 2013; Barad 2007; Hodder 2012 is more specific in his definition) of many different representational and ideological models constructed and employed by historians and archaeologists of the past 200 years. Furnished burial practices in the later Roman empire are inextricably bound to a number of key issues in interpretations of the late Roman West, with a long historiography of study that extends across numerous languages and international scholarly traditions. Over time, the archaeological data has accrued a number of added meanings, with each interpretation contributing to an entangled interpretive web, which transforms the way that scholars perceive the data (cf. Pitts, this volume, on the web of representational interpretations and labels attached to pottery). Firstly, the fact that the vast majority of the ‘soldier burials’ have been excavated in northern Gaul and the Rhineland has artificially privileged particular associations between the archaeological data and related socio-political explanatory models from those regions. Second, the model blends the binary opposites of ‘Roman’ and ‘barbarian’ burial practice, the roles of artefacts as signifiers of personal identity, and textual evidence for barbarian migrations. Even when the evidence for barbarian migration or ethnic identification is challenged, as with Halsall and Theuws, there is still a blending of the concepts of identity, burial practice and the role of Roman political hegemony; the difference is the degree to which particular types of objects are understood as having different kinds of representational roles. What is not contested, however, is the representational association of crossbow brooches and belt equipment with the imperial state or military.

At the same time, the models discussed above have not been applied to equivalent graves from late Roman Britain. There is no historical evidence attesting to widespread barbarian migration or settlement in the later fourth century AD, so the barbarisation of the population of Britain can be more easily dismissed. In addition, the occurrence of the graves is much more limited in quantity and geographical range; furnished late Roman burials bearing artefacts identified as military equipment constitute a firm minority of graves excavated to date. How should these graves be interpreted?

Graves furnished with military equipment in late Roman Britain are limited in number and distinctly clustered. The largest group is found in the cemetery at Lankhills outside Winchester, consisting of 23 burials with military equipment out of a total of 783 graves, from two excavation campaigns (Clarke 1979; Booth et al. 2010). Scorton, north of Catterick, has a small cemetery of six soldier graves from a total of 15 (Eckardt et al. 2015). While the Eastern cemetery of Roman London had a total of 851 burials investigated, only one of these can be identified as a soldier burial (Barber and Bowsher 2000). From a small group of eight burials at Kingsholm Drive, Gloucester, another single grave was identified (Brown 1975). A single burial was also located against the external wall of a second century AD mausoleum at Shorden Brae outside the Roman town of Corbridge (Gillam and Daniels 1961), and there are two notable burials at the site of Dyke Hills at Dorchester on Thames (Kirk and Leeds 1954; Booth 2014).

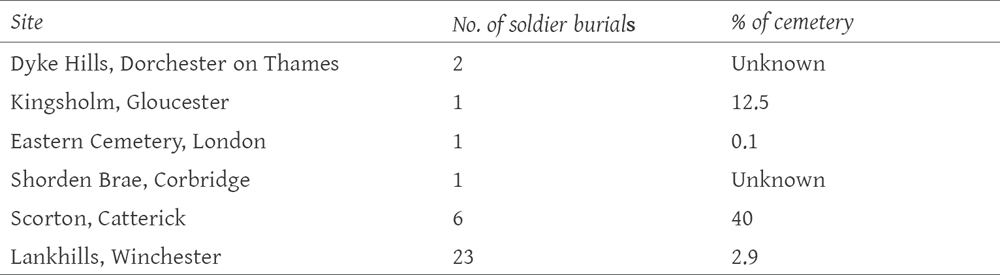

Table 3.1 The number of soldier burials, as determined through grave goods, indicated in terms of real numbers and as a percentage of the total burials per cemetery.

Table 3.1 reveals the rarity of fourth to fifth century AD burials furnished with military equipment, with only 34 individuals that could qualify as possible soldiers. While Lankhills provides the largest number of burials with crossbow brooches and belt sets, these only constitute 2.9% of the total number of burials (inhumation and cremation). The one burial from the Eastern cemetery in London represents 0.1% of the burials investigated in that cemetery. For Shorden Brae and Dyke Hills, however, it is difficult to determine how these individual burials compare to the larger cemeteries as neither site has received full excavation. In contrast, the cemetery at Scorton provides a significant group, with a very high proportion of graves containing military equipment (40%), and its separation from nearby cemeteries at Catterick (Eckardt et al. 2015).

More detailed examination of a sample of the total burials reveals the variability within this group (Table 3.2). While most of the burials were inhumations, there are examples of cremations, for example grave 895 from Lankhills with a fragmentary crossbow brooch and a probable belt buckle plate as pyre goods (Booth et al. 2010, 238). Burials containing weapons are extremely rare. Only the two graves from Dyke Hills are comparable to the rite in northern Gaul and the Rhineland (Booth 2014, 260–2). It is possible that knives may be an important signal for a British variation of this rite, with the knife acting as a substitute for other weaponry. The Kingsholm, Gloucester burial and three of the six burials from the more recent excavation campaign at Lankhills included knives. Not all knives are the same, and some distinction can be made in regards to the knives from Lankhills (Cool 2010, 276–7). However, it is likely that only some knife-forms may be understood as weapons, and it is noteworthy that most graves containing military equipment do not contain knives.

The most important feature of the British graves seems to be the presence of crossbow brooches and belts. Table 3.2 has only one example of a burial with a crossbow brooch without any associated belt equipment, from Shorden Brae, Corbridge, but other examples are known from Britain, such as a burial from the fort of Binchester excavated in 2016 (D. Petts, pers. comm.). All other burials containing brooches also feature belt equipment. It is worth noting that there are seven graves containing belt equipment in Table 3.2 but lacking a crossbow brooch.

Table 3.2 A selection of soldier burials by site, separating the contents of the grave. An asterisk (*) indicates a cremation; all other graves are inhumations. The date of burial has been given as a TPQ based on the chronology of artefact typologies, unless a C14 date is also available.

For those graves featuring belt equipment, three simple groupings can be distinguished, based on the collation of belt components. The most likely component of a belt to be encountered is a buckle (complete or evidenced only by a frame and/or plate), seen in nine burials; less frequently another element is the only evidence, for example the strap end from grave 1075 at Lankhills. The next most common occurrence is a buckle and strap end, although there may be one or two other simple components like a suspension ring. The belts that are most exceptional in terms of rarity and quality are those bearing five or more elements, for example those from the Eastern cemetery, London and Dyke Hills. The Dyke Hills belt from grave 1 has at least 20 surviving components, consisting of a buckle, strap end, and a number of stiffeners and suspension loops (Kirk and Leeds 1954). The belt from grave 538 at the Eastern cemetery, London has only five components, but these consist of large, ‘chunky’, chip-carved pieces of the buckle, strap end, and three end plates/mounts (Barber and Bowsham 2000, 206–8). These two examples contrast with the majority of other belts, which have fewer surviving elements. The most important point, however, is that simple belts with only a buckle or a buckle and strap end are the most likely to be encountered. This further underscores the presumed high status of the individuals buried at Dyke Hills and London’s Eastern cemetery.

The typologies of the brooches and belt equipment are also worthy of attention, at least in brief, following the crossbow brooch typology of Pröttel (1988) and modified by Swift (2000). Within those graves containing crossbow brooches, nine are of type 3/4, one of type 2, and two of type 6. Type 3/4 crossbow brooches are the most widespread and frequent, and probably are representative of the crossbow brooch at its peak usage dating roughly to AD 340–420 (Swift 2000). Type 2 tends to be an earlier form dating to the first half of the fourth century, and type 6 dates roughly to AD 390–430. It is no surprise that the majority of crossbow brooches can be assigned to type 3/4, and those associated with belts tend to be associated with simpler belts consisting of 1–4 surviving components. The type 6 crossbows are found in the burial with no associated belt at Shorden Brae and from the burial with the impressive chip-carved belt from the Eastern cemetery, London. Type 6 crossbows are known to be associated with the highest echelons of imperial society through art historical evidence such as the Stilicho diptych, and therefore should not be presumed to be exclusively military in their association. This ambiguity perhaps explains why the Shorden Brae burial lacked a belt and why the burial from the Eastern cemetery had such an elaborate belt despite being broadly contemporary.

While the potential insight gained through typological analysis and association can be useful, a number of concerns must also be addressed. In the first instance, although a broad typology and chronology is accepted for crossbow brooches, it has been widely accepted that a looser typology has to be employed in Britain, to reflect variation through local production (Swift 2000, 211; Cool 2010, 279; Collins 2015, 474). Furthermore, the broad types of crossbow brooches can be associated with independent dating information such as coins from graves and stratified deposits, but less dating evidence is available for examples in Britain. In addition, there is good evidence to suggest that crossbow brooches were curated and enjoyed a long use-life, as observed at Lankhills and Scorton (Cool 2010, 284; Eckardt et al. 2015, 7).

Accepting arguments for the localised production of crossbow brooches in Britain and their long lives raises further questions about the production and distribution of brooches. Was there any mechanism of control over who could produce crossbow brooches? If not, were locally made brooches still deemed ‘official’, or even visually distinguished by their wearers and viewers? Once produced, how were the brooches distributed, through imperial channels and officials, or were they available to a wider public? These concerns and questions regarding crossbow brooches equally apply to belt equipment.

The strong association of crossbow brooches and belt equipment with adult males is beyond question, as demonstrated at Lankhills and Scorton (Cool 2010, 283; Eckardt et al. 2015, 7), but are these men soldiers? And if so, what type of soldiers? In principle, the late Roman army was separated into three tiers: the limitanei permanently garrisoned in the frontiers, the comitatenses that formed the regional field armies, and the palatine that served in the armies attached to the emperors. In practice, these three arms were not kept separate, as offensive and defensive operations would see the comitatenses and the palatine armies work alongside the limitanei. However, there were practices that distinguished these branches, for example, recruitment and supply. Supply is a particularly important issue here, since the production of equipment like brooches and belt elements will have come from different workshops. There is reasonable evidence for local production of belt equipment along Hadrian’s Wall, in the form of a casting template of a strap end for making moulds at Stanwix fort, and an unfinished strap end from the fort at South Shields (Coulston 2010). The army was led by a professional officer class, and perhaps brooches (if not belts) were restricted to certain groups within the army. As noted above, the type 6 crossbow brooch was associated with the upper echelons of imperial society, who may not have been soldiers.

Certainly, it seems probable that these brooches were worn by soldiers, or their officers, but the brooches may not have been the exclusive preserve of soldiers. Roman Winchester was not known as a military base, which raises the question: who were these men wearing crossbow brooches and belts? Were they soldiers detached from their home base on another duty, veterans, or another group not officially linked to the army? In this regard, typological variation in buckles may be quite significant. Scholarship in Britain has tended to focus on the zoomorphic forms studied by Hawkes and Dunning (1961), but this preoccupation may be obscuring associations that can be made between particular buckle forms and belt equipment and different types of soldiers or state civilian officials. Scorton, outside of the Roman fort and town at Catterick, may provide a clearer case for soldiers/officers bearing military metalwork, though Eckardt et al. (2015, 27) wisely note that it may not be possible to distinguish between military and civilian administrative personnel in imperial service. However, it may be significant that none of the buckles from Scorton are zoomorphic forms, in contrast to examples from Lankhills and Dyke Hills.

Isotopic evidence has been able to reveal another interesting facet regarding the origins of some of the individuals under consideration. The individual in the recently recovered weapon burial at Dyke Hills is likely to have originated in continental Europe outside the Roman empire (Booth 2014, 268). Analysis of the individual in the Kingsholm burial at Gloucester suggests migration from southeastern Europe or southern Russia, which fits with the geographic associations of the artefacts from the grave (Evans et al. 2012). At Scorton, isotopic analysis revealed that a central European origin was likely for the individuals buried in graves 1, 5, 6 and 7, and non-local (though possibly still British) origin for the individuals in graves 12 and 14 (Eckardt et al. 2015, 24). All the men buried with military equipment at Scorton appear to be non-local, based on comparison of the isotopic signatures from individuals at Scorton with individuals and livestock from other cemeteries associated with the Catterick fort and town.

It remains the case that the diverse geographic and likely cultural origins of these individuals are linked by the objects with which they were buried, and by the burial rituals observed. The male buried in grave 12 at Scorton was not locally raised, but he was also isotopically distinct from the other men buried in the cemetery, indicating a different geographic origin; despite this, his burial was still consistent with the other men, including a buckle and other objects (Eckardt et al. 2015, 26). At Lankhills, men buried with both imported and ‘hybrid’ crossbow brooches of probable British manufacture were demonstrated to have foreign isotope profiles (Cool 2010, 283). These examples further indicate the significance of crossbow brooches and belts, such that ‘status in the sense of a professional identity and as expressed through objects which are almost like insignia of office was more important than geographical origin or ethnicity’ (Eckardt et al. 2015, 26). This suggests that brooches and belts in the fourth and fifth century AD were material markers of the phenomenon of occupational identity, which has been attributed to the Roman army elsewhere (Collins 2006; 2012). This does not change the representational nature of crossbow brooches and belt equipment, but shifts its significance away from geographic or ethnic associations to one of occupation.

In contrast to the continental evidence, the distribution of later fourth and early fifth century graves with military equipment in Britain does not correspond with the militarised frontier zones. While the burials at Shorden Brae, Corbridge and Scorton, Catterick, fall within the northern frontier zone, it is worth noting that Corbridge was not a fort and Catterick was home to both a fort and sizeable extramural urban settlement. Roman Winchester and Gloucester were both cities, and Dorchester-on-Thames was a smaller civilian centre. London, of course, was the capital of the diocese of Britannia. The fact that the burials are associated with urban settlements does not preclude the possibility that the deceased were soldiers, but rather contextualises the connected environment in which these prospective soldiers lived.

The furnished ‘soldier burials’ from the south contrast with a dearth of funerary evidence from the northern frontier zone. Four inhumation graves found outside the southwest gate of the fort at South Shields, located at the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall, contained only human bone. There was no evidence for accompanying grave furniture or goods, though the burials could be confidently dated to the fifth century AD based on the terminus post quem of the stratigraphic sequence and C14 samples (Snape 1994, 143–4). More recent excavations outside the Hadrian’s Wall fort of Birdoswald and at the coastal fort at Maryport have revealed a further ten graves that appear to date to the late fourth century AD or later. Analysis is still in progress, but what is significant is that these were characterised by stone cists or simple earth-cut graves without grave goods, with the exception of one grave with a bead necklace at Maryport. This small sample may prove to be the normal burial rite in the Wall corridor, making it difficult to identify any of the deceased as soldiers, even if this is likely. The discovery of a new furnished cemetery in this area would dramatically change the current picture, but on existing evidence it is important to stress the contrast between this small handful of late Roman burials from the Wall and the ‘soldiers’ buried further south.

How can this contrast within Britain, and the contrast between Britain and northern Gaul and the Rhine limes be explained? Theuws’ model, that the graves indicate new claims to land, does not readily apply to Britain; there is no evidence for Britain suffering from the same settlement abandonment and shrinkage in the later third and fourth century as northern Gaul. Halsall’s model, that the graves signal increased local competition in an environment of reduced imperial control, may have more validity. But the difference in the distribution of military burials suggests a different sense of local competition. In Britain, ‘soldier burials’ can be generally associated with urban settlements, though this is not necessarily the case in northern Gaul or across the Rhine in barbaricum. Furthermore, there is little association of the funerary ritual with military bases in Britain, even though these sites were still occupied.

If the burials can be accepted as representing soldiers or civil military officials (still unproven, if likely), then it must be concluded on present evidence that there is an important difference in the way that these identities were expressed in the mortuary ritual in southern Britain. Following Halsall’s argument, it may be the case that the ritual was being used to emphasise military identity in a locality where it was under pressure from other elite roles and identities. In northern Britain, where soldiers were more common, there was likely to be less competition between military elites and civilian power structures. Alternatively, the presence of soldiers may have been so commonplace that it was unnecessary to emphasise aspects of occupational identity in the mortuary sphere through inclusion of military equipment.

Perhaps at present, ‘soldier burials’ are too limited in number in Britain to draw firm conclusions, although artefacts are clearly crucial to solving the dilemma. Further work is required on artefact typologies and chronologies, and the associations between individual types, particularly for belt equipment from Britain. In this regard, Britain is particularly well-served by data from the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which should help to further distinguish between the broad patterns of typological distribution and examples associated specifically with mortuary activity.

A more fundamental question for further research concerns the utility of representational readings of objects. Accepting a simplistic representational reading is a potentially damaging first step; a representational role has already been broadly applied to nearly all crossbow brooches and belt equipment. The more pressing challenge is to not allow a representational reading to mask significant patterning and nuances within the data. At one level, crossbow brooches and belt equipment were explicitly and conscientiously used in a representational fashion by the Romans themselves. However, for a more analytical approach, it is necessary to push beyond the simple acceptance of these representational readings, and to give much closer scrutiny to the diversity of form and the archaeological contexts of the objects in question.

One suggestion for advancing analysis is to accept the representational role of particular types of material culture in societies as a circulating reference, as defined above. The crossbow brooch and military belt would be widely recognisable as symbols of the military and by extension of military privilege in late Roman society. However, the way in which the military was situated within any particular region or locality would have varied. Therefore, while symbols of military authority must have had universal recognition, the reception and use of such symbols was open to variation. Framing particular objects as circulating references not only embraces their representational role, but prompts archaeologists and historians to explore the complexity and nuances of how representational artefacts functioned in the past and in contemporary research.

I would like to thank my colleagues at Newcastle University, James Gerrard and Chris Fowler, for discussion which helped me to formulate thoughts in this chapter. Observations and discussion at the Rethinking Artefacts in Roman Archaeology seminar helped to frame the chapter. Thanks to Hella Eckardt (Reading University) and Greg Speed (NAA) for permission to reproduce the image of grave 14 from Scorton.

* School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University.