"Eat something green every day" is age-old motherly advice. Generations of kids have heard it as they scrunched up their faces and downed a forkful of spinach or broccoli.

Today, Mom's old advice has gotten an update: Eat everything green every day. You don't have to become a vegetarian (although, as The Meat Industry's Environmental Hoofprint notes, you'd reduce your carbon footprint if you did). Eating green means saying no to farming practices that harm the earth and treat animals as assembly-line products; choosing foods that aren't drenched with synthetic insecticides, weed-killers, and other potentially harmful chemicals; and, if possible, growing your own fruits and veggies to get the freshest, healthiest food possible.

This chapter looks at current farming practices—the good, the bad, and the unappetizing—and how they affect the food you eat so you can make informed choices. You'll also learn all kinds of tips for growing your own food—even if you're a city dweller.

Some claim it's the pinnacle of American cuisine: a ground-beef patty with a slice of melted cheese served on a bun (pickles optional). In the U.S. alone, people eat more than 13 billion cheeseburgers each year, which works out to about one or two every week for the average American carnivore.

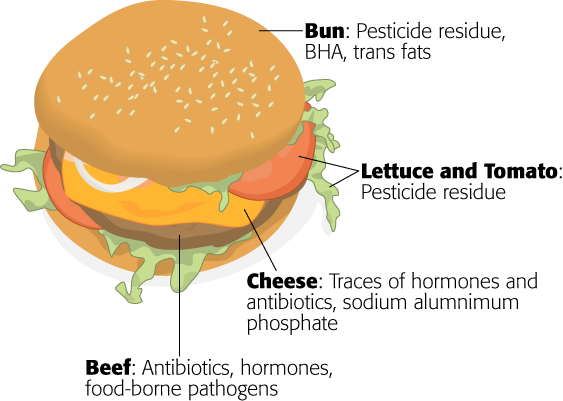

When you stop by your favorite fast-food place and order a nice, juicy cheeseburger, what are you really getting? Here's some info that might quell your appetite:

Bun. The wheat used to make the buns was sprayed with pesticides and fungicides, and traces of these chemicals may remain. Butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), often used as a preservative in baked goods, causes cancer in lab animals at large doses. And even though many fast-food restaurants have stopped using trans fats in their cooking, these fats—which increase your risk of heart disease and diabetes—are still found in many baked goods.

Cheese. Diary products may contain growth hormones (the box on Concern #3: Factory farms misuse hormones and antibiotics. explains why that might be a problem) and antibiotics. And eating large amounts of alkaline sodium aluminum phosphate, used as an emulsifier in cheese, makes it harder for the body to absorb calcium and phosphorous, two important nutrients.

Beef. The antibiotics and hormones used on cattle (Concern #3: Factory farms misuse hormones and antibiotics.) can get into the meat you consume. According to the Center for Food Safety, several of these hormones likely have bad effects on people, including cancer and impacts on child development. The European Union has banned U.S. beef since 1985 because of concerns about hormones. The cattle may also be infected with antibiotic-resistant strains of food-borne bacteria, such E. coli.

Lettuce and tomato. There could be pesticide residue on the veggies in your burger. These chemicals kill insects, mold, and other pests, so it's no surprise that they may pose dangers to humans, too. The Pesticide Action Network reports that chemicals commonly used on lettuce and tomato crops include diazinon, maneb, chlorothalonil, dimethoate, and methoxyfenozide—all of which can cause cancer, birth defects, infertility, and developmental problems.

Most of those 13 billion cheeseburgers get wolfed down without a thought. But the next time you're stomach's rumbling, think about what's in the food you're about to eat, and consider healthier alternatives (this chapter offers lots). Knowing where your food comes from is half the battle.

When people think of a farm, many imagine animals grazing in green pastures, a big red barn, and a few chickens scratching around the barnyard. But that idyllic picture couldn't be more different from the realities of 21st-century farming. Small family farms are giving way to factory farms, huge operations that treat agriculture as an industry rather than a way of life. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), between 1974 and 2002, the number of corporate-owned U.S. farms increased by 46%, with the largest 1.6% of farms accounting for half of American agricultural production. That means big farms are getting bigger.

The food in your local grocery store likely came from a factory farm, a big, industrialized facility that produces large quantities of food. Animal farming lends itself to this practice more easily than grain farming, so the term "factory farm" usually refers to an agribusiness that raises large numbers of animals to slaughter weight in the shortest time possible.

The U.S. EPA calls these farms concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). As that name suggests, these are crowded farms that are more concerned with keeping animals alive until it's time to butcher them than with giving them any decent quality of life. And as the EPA defines it, a CAFO is an agricultural operation that keeps animals confined. So instead of being sent out to graze in a pasture, animals get fed in their stalls, cages, or other enclosed area, and the animals are kept in this confinement for at least 45 days in any 12-month period. Table 6-1 shows how the EPA defines medium and large CAFOs for different kinds of livestock.

Table 6-1. How the U.S. EPA Defines Factory Farm Size

|

Type of Animal |

Number of Animals | |

|---|---|---|

|

Medium CAFO |

Large CAFO | |

|

Cattle or veal calves |

300–999 |

1,000 or more |

|

Dairy cows |

200–699 |

700 or more |

|

Swine (less than 55 pounds) |

3,000–9,999 |

10,000 or more |

|

Swine (over 55 pounds) |

750–2,499 |

2,500 or more |

|

Sheep and lambs |

3,000–9,999 |

10,000 or more |

|

Turkeys |

16,500–54,999 |

55,000 or more |

|

Laying hens or broilers (with a liquid manure handling system[a]) |

9,000–29,999 |

30,000 or more |

|

Laying hens (with other manure handling system) |

25,000–81,999 |

82,000 or more |

|

Chickens other than laying hens (with other manure handling system) |

37,500–124,999 |

125,000 or more |

[a] A liquid manure handling system uses water to flush chicken excrement into storage areas, which can be large, smelly, open lagoons. This creates a lot of pollution, so the EPA considers a poultry farm that uses this kind of system "large" based on a much smaller number of animals. | ||

Why, you might wonder, is the EPA involved in farming? Because the waste produced by big farms can cause significant harm to the environment. Large and medium CAFOs have to comply with the Clean Water Act to minimize the pollution they cause. (For more on factory farms and the environment, flip ahead to The Meat Industry's Environmental Hoofprint.)

Proponents of factory farms argue that they're more efficient than traditional farms—they produce more food faster and more cheaply. That means more affordable food, which helps address the hunger problem that prevails in many parts of the world.

Opponents question whether a corporate structure that values efficiency above all else is appropriate for farming. These voices call for smaller farms that use sustainable practices to produce fresh food that will be eaten locally, putting food production and environmental stewardship in the hands of local communities.

Note

In the U.S., approximately 10 billion animals are slaughtered for food each year. That's about 33% more animals than the human population of the entire planet.

As factory farming has grown more widespread, environmentalists, ethicists, scientists, and others have raised concerns about its practices. The sections that follow give a brief overview of these issues.

The numbers in Table 6-1 are minimum thresholds. In practice, large CAFOs may be much, much bigger, cramming far too many animals together in far too small a space. For example, a cattle feedlot, where young cows are severely confined and fattened up before slaughter, may have tens of thousands of animals, while a large-scale egg farm may have a million chickens. The sheer size of such farms presents difficulties in caring adequately for the animals and managing their waste.

Animals on factory farms live in appalling conditions. Crammed into narrow pens and cages, they have little or no freedom to move around. Laying chickens spend their lives in crates that are smaller than a cubic foot, giving them about as much floor space as a sheet of copy paper. And some animals are mutilated to make them easier to handle—for example, chickens and turkeys may have their beaks cut off so they won't peck each other in tightly packed cages. And pigs and cattle may be castrated, dehorned, or have their tails cut off—without anesthesia. Animals may be transported in overcrowded trucks for long distances without food, water, rest, or protection from the elements. In poultry-processing plants, chickens are sometimes scalded, skinned, and dismembered without first being killed or even stunned.

Note

Although all 50 U.S. states have animal-cruelty laws, most exempt working farms from these laws. So factory farms get away with treating animals in ways that ordinary citizens would get arrested for.

Many people question the ethics of treating animals as nothing more than products to be processed. Even animals destined for the slaughterhouse, they argue, deserve humane treatment while they're alive. Governments are responding to these concerns:

In 1979, the British government created the Farm Animal Welfare Council, which acts on the principle that farm animals are entitled to five freedoms: freedom from hunger and thirst; freedom from discomfort; freedom from pain, injury, and disease; freedom to express normal behavior; and freedom from fear and distress.

Gestation crates, which confine pregnant sows in a space so narrow they can't turn around or even lie down comfortably, are already banned or are being phased out in the European Union and several U.S. states.

Battery cages, which confine egg-laying hens, and veal crates (two-foot-wide cages where calves are confined for their short lives) are also subject to bans and phase-outs in European countries and U.S. states.

Note

Maybe you buy "free-range" meat and eggs thinking this label means the animals are treated humanely. But the reality may not match your understanding of the term. The USDA defines "free-range" poultry as birds that have access to the outside, so a farmer could open the coop door for just a few minutes a day and call his products "free-range."

Note

Farm Sanctuary, which has facilities in California and New York, educates people about how factory farms treat animals and offers refuge to farm animals. Its website (http://farmsanctuary.org) has tons of info about factory farming and stories of rescued animals that now live at Farm Sanctuary.

Factory farms are in a hurry: The faster they can slaughter animals, the more money they make. So these farms use pharmaceuticals as a shortcut, giving animals hormones and antibiotics to make them grow faster. The box on Concern #3: Factory farms misuse hormones and antibiotics. has info about the hormones used in beef cattle and dairy cows and the threat that these may pose to people's health. The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates that 70% of all antibiotics produced in the U.S. are given to livestock—that's eight times the amount used to treat people. And the animals aren't even sick: The drugs prevent disease and accelerate growth.

Those drugs can make their way into the meat and milk people consume. Hormones, given to two-thirds of U.S.-raised cattle, may promote cancer: breast and reproductive-system cancers in women and prostate cancer in men. See the next section for more on the problems with giving nontherapeutic antibiotics to farm animals.

Note

The USDA doesn't let farmers use hormones on hogs or poultry. So you won't find the phrase "no hormones added" on pork or poultry product labels unless there's also a statement explaining, "Federal regulations prohibit the use of hormones." Since farmers can't give these animals hormones, the USDA reasons, it's misleading to imply that leaving hormones out is an advantage.

It's not a very appetizing thought, but a lot of food-borne illnesses come from animal feces contaminating food. The conditions in factory farms—where tightly penned animals sometimes stand in mounds of manure—and large slaughterhouses can cause the food they produce to get contaminated. Outbreaks of things like E. coli and salmonella have increased right along with the rapid growth of factory farming.

One of the main concerns about factory faming practices and disease is the way these farms use antibiotics, which may contribute to the development of so-called superbugs, antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria. An example of a superbug is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a potentially fatal staph infection that resists the broad-spectrum antibiotics typically used to treat such infections. These superbugs can be passed to people, and they're really hard to treat.

The Union of Concerned Scientists is lobbying to keep farms from putting seven kinds of antibiotics that are important to human medicine into animal feed: penicillins, tetracyclines, macrolides, lincosamides, streptogramins, aminoglycosides, and sulfonamides.

Some practices used by factory farms decrease the nutritional value of meat from the animals they raise For example, meat and milk from grass-fed cows have more conjugated linoleic acid (CLA)—an antioxidant that may fight cancer and help with weight loss—than feedlot cattle. Grass-fed beef also has more omega-3, a heart-healthy fatty acid that's essential for normal growth.

Similarly, meat from pasture-raised chickens (those that don't live in crowded pens) has less saturated fat and about a quarter fewer calories than meat from their factory-farmed counterparts. According to the group Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education, eggs from pasture-raised hens have 10% less fat, 40% more vitamin A, and 400% more omega-3 fatty acids than eggs from factory farms.

So what do factory-farmed animals eat, anyway? You know the phrase, "You are what you eat"? The idea is that good nutrition equals good health. If you consume factory farm–raised meat, though, you're eating what those animals ate, which may include:

Other animals. If you think cows eat grass, pigs eat table scraps, and chickens eat seeds and grubs, think again. On factory farms, animals can legally be given feed made from ground-up animal parts, including bones, blood, intestines, feathers, hair, skin, and hooves. (An exception is that cows can no longer eat feed made from certain parts of other cattle, in an effort to combat mad cow disease.) The feed may also contain parts of dead horses, roadkill, and euthanized cats and dogs.

Manure. Believe it or not, manure from cattle, pigs, and poultry is a common ingredient in animal feed.

Plastic. Yes, you read that right. Plastic has no nutritional value, but because animals on factory farms eat manufactured feed instead of the food their bodies are designed for, many don't get enough roughage, the dietary fiber they need to stimulate their intestines. So some factory farms use plastic pellets to make up for the lack of natural fiber in the animal's feed.

Grain. Finally, something that's good for the animals, right? Not all of them. Cows, for example, aren't designed to eat the grain-rich diet that's used to fatten them up for slaughter, and such food can cause problems with their digestive systems and livers.

The USDA estimates that between 2005 and 2006, the United States lost 8,900 farms—that's about a farm an hour. One major cause is the agribusiness industry. Large factory farms can take advantage of government subsidies that are out of reach for smaller operators. Just four industrial farming firms make up 60–80% of the important agriculture markets in the U.S., including beef, poultry, and pork processing. This near-monopoly prices smaller producers out of the market.

Some people think that family farms are the agricultural equivalent of eight-track tapes and typewriters: an outmoded way of doing things. Family farms, they argue, may be a nice, nostalgic idea, but if they can't produce food as efficiently and cheaply as large-scale corporate operations, perhaps their time has come and gone. This argument ignores several important aspects of family farms:

Most farming families live on the farms that they tend. That means they have more respect for the land and care for it better because it's more than a means of income—it's their home. For this reason, family farms tend to be greener than corporate farms.

Family farms sustain local economies. Small farms hire local help and buy supplies from local businesses. Factory farms, on the other hand, are designed to produce the maximum about of food with the minimum number of workers, and they usually buy supplies from outside the area and truck them in, adding to traffic and air pollution.

With local family farms, you know where your food came from. You can talk to the farmers who produced it, and you know it's fresh because it came from right down the road. With corporate farms, the people in charge are often in offices far away from the land their company farms. Factory farms are less interested in feeding the local community than in transporting their products to wherever they can get the best prices.

If these benefits of family farms are important to you, seek out local, seasonal food to support them, rather than buying whatever's cheapest.

Tip

The Slow Food movement promotes local food that's sustainably grown, and the idea that food is "a cornerstone of pleasure, culture, and community." To become a slow foodie or just learn more about the movement, visit www.slowfoodusa.org.

When you think about the countryside, you probably imagine green fields and fresh air. That's not what it's like near a factory farm, though: They stink. People living near hog farms, for example, have higher-than-normal rates of respiratory problems, runny noses, sore throats, burning eyes, and headaches. A factory farm also causes increased traffic in the area (from trucks bringing in supplies and carrying animals to slaughter) and can lower property values.

The smell that comes from factory farms isn't the biggest problem for the surrounding area. These farms pose a serious threat to the environment. When you've got thousands of animals crowded together, all the manure they produce has to go somewhere. Unfortunately, much of it pollutes the air and water around the farm—and adds masses of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. The next section has more info about the impact factory farms have on the environment.

As you learned in the previous sections, industrialized farming raises concerns about health, humane treatment of animals, and farming communities. Another big concern for people who want to eat green is how the meat and dairy industries affect the environment. These farms pollute the air, water, and earth, and have a massive carbon footprint. Way back in 1997, a report by the U.S. Senate Agricultural Committee warned, "The threat of pollution from intensive livestock and poultry farms is a national problem."

There's no getting around the fact that lots of animals equals lots of manure. On many farms, that waste goes into huge, open-air, artificial lagoons. In fact, "huge" may be an understatement: On a big factory farm, a lagoon may span 5–7 acres and contain 20–45 million gallons of waste. Aside from the obvious stench, these lagoons also pollute the air with chemicals including ammonia, methane, and hydrogen sulfide.

In the U.S., it's the EPA's job to make sure that factory farms comply with the Clean Water Act. Still, pollution happens. In fact, the EPA estimates that hog, chicken, and cattle waste has polluted 35,000 miles of rivers in 22 states and contaminated groundwater in 17 states.

Some farms spray liquefied manure on crops as a fertilizer, which may contain bacteria and cause food-borne illness. The manure can also run off and contaminate streams, rivers, and lakes, pollute drinking water, kill fish, and disrupt ecosystems.

But in this era of rapid global warming (Why We Need New Energy Sources), one of the biggest problems with the meat industry is the amount of greenhouse gases livestock produce. According to the U.S. EPA, worldwide livestock farming releases more methane—a potent greenhouse gas—than any other human activity. Globally, such farming sends about 80 million metric tons of methane into the atmosphere each year—much of that from animals' flatulence and burping—which is about 28% of all methane released by people's activities. Other greenhouse gases produced by livestock farming include nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide.

Different kinds of animals create different amounts of greenhouse gases. The U.K. Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs says that beef and lamb have the biggest carbon footprint: Each ton of meat accounts for 16 tons of carbon dioxide. Pigs and poultry have a smaller (but still significant) carbon footprint: five tons of carbon dioxide per ton of pork and four tons for chicken.

So what can you do to reduce the greenhouse-gas emissions from farming? The best thing is to reduce demand by eating less meat. A Carnegie Mellon University study concluded that each person who shifts from a meat-based diet to a vegetable-based one reduces greenhouse-gas emissions by the equivalent of driving 8,000 fewer miles.

Note

Journalist Jamais Cascio calculated the energy costs of producing a cheeseburger: the farming, production, transportation, cooking, and so on. He figured that each year, all the cheeseburgers eaten in the U.S. are responsible for between 65 million and 195 million metric tons of greenhouse gases. That's the same amount of gases emitted by 6.5–19 million SUVs in a year. To see how Cascio crunched the numbers, go to http://openthefuture.com/cheeseburger_CF.html.