11

An Unfortunate Turn

ALTHOUGH THE BRITISH AND AMERICANS DIFFERED OVER WHETHER Iran was on the brink of collapse, the Iranian government’s decision to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in 1951 came at a time when the country was in a parlous state. Anglo-Iranian’s effective concealment of its profits meant that oil revenues represented only a small fraction of Iran’s national income. The country remained an impoverished, predominantly agrarian economy. Well over half its seventeen million people were illiterate peasant farmers who scraped a living on plots they rented from absentee landowners, selling any surplus locally. Their livelihoods had been badly affected by wartime occupation and inflation; widespread crop failure in 1949–1950 made matters worse, quickening an exodus from the countryside to the cities, especially Tehran.

A lack of political leadership left Iran ill equipped to cope with the challenges of rapid urbanization. The shah, whom Wendell Willkie had encountered as a twenty-two-year-old, was now thirty-one. But he remained an unimpressive character, who, in an American analysis, could not “make up his mind whether he should reign or rule, and consequently does neither.” Backed by the army, he was jockeying for power with the tiny clique of landowners, tribal leaders, merchants, clerics, and army officers who formed the country’s ruling class. Iran’s parliament, the Majlis, was small enough to be controlled by the clique, whose vested interest was the perpetuation of the status quo. In the absence of effective political parties, Iranian politics resembled a carousel of familiar, ageing faces who headed up governments that lasted, on average, just six months. An MI6 officer recommended Through the Looking Glass to anyone who was trying to get their head around the country.1

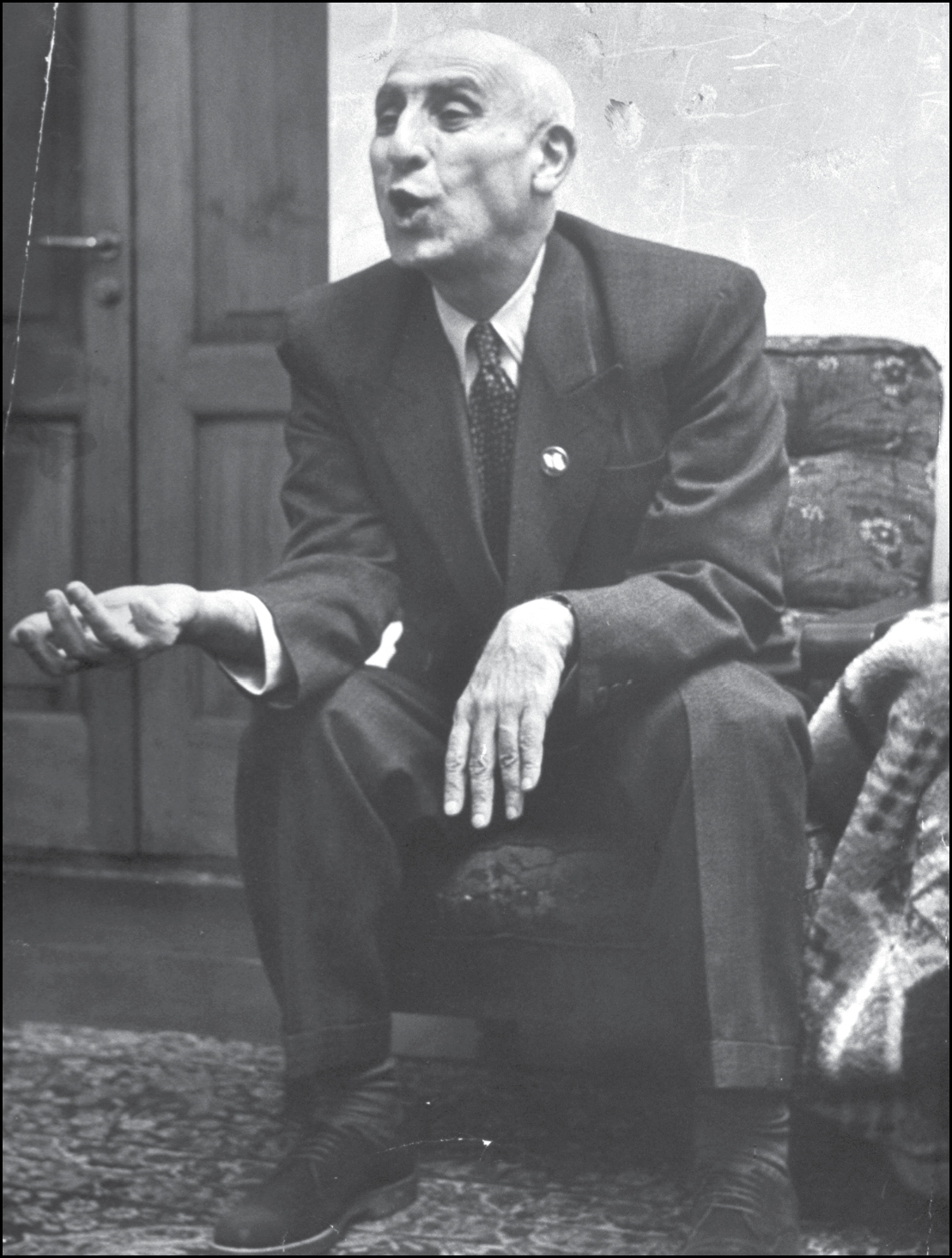

MOHAMMED MOSADDEQ WAS one of a growing number of Iranians who were fed up with this situation. A tall, thin, bald man, whose beaky nose and jerky movements invited comparisons to a bird, he came from the very milieu he criticized. His mother was a princess of the dynasty that had ruled the country throughout the nineteenth century; his father had once served as finance minister. So, indeed, had he, under the previous shah. But during this time, he had established himself as an opponent of corruption and foreign influence—so much so that, during the war, the British had encouraged him to campaign against Russian attempts to acquire an oil concession in the north of the country.

That move would come back to bite the British when they became Mosaddeq’s next target, but it is easy to see why they had enlisted his support. Mosaddeq was a powerful and histrionic speaker whose looks and ascetic lifestyle led one British diplomat to describe him as “a sort of Iranian Mahatma Gandhi, but less rational.” Aged sixty-nine or seventy-nine by 1950, depending on which date of birth you chose to believe, he was beset by a chronic illness that left him frequently exhausted and prone to faint. In one celebrated incident, he collapsed halfway through a speech in the Majlis. Another deputy, a doctor, pushed through the scrum that had formed round him to check his pulse. As he did so, the apparently unconscious Mosaddeq slowly opened one eye and winked at him. Clever, slippery, and unscrupulous though he was, “one could not help but like him,” said the U.S. diplomat George McGhee.2

Anglo-Iranian’s officials do not seem, initially, to have been overly worried by Mosaddeq because they misunderstood him. Until that point in time, they had resolved all their difficulties with money. They had bribed government ministers and officials, deputies and senators in the Majlis, and perhaps the shah as well, in order to persuade him to accept the 1949 Supplemental Agreement. They even discredited their opponents by paying newspapers to run articles claiming that these people were in the company’s pay.

Anglo-Iranian’s mistake was to assume that these time-honored techniques would also defeat Mosaddeq. After the Iranian took over the chairmanship of the Majlis’s oil committee, the company’s officials drew up a list of the eighteen-strong panel’s members, together with notes on their finances, political allegiances, and family links. It was a preliminary to the bribery of the thirteen deputies on the committee who were not members of the National Front, but it did not succeed.3

The problem for the company was that Mosaddeq was not interested in money. He “did not care about dollars, cents or numbers of barrels per day,” wrote one Iranian official. “He saw the basic issue as one of national sovereignty.” In mid-October the National Front staged a four-day-long debate in the Majlis to expose the oil company’s techniques and blame its corrupting activities for the state of the country. Such was the success of this onslaught that once dependable supporters of the company became reticent about expressing pro-British views, fearing that by doing so they would invite accusations of corruption and treachery.4

As a result, when Mosaddeq then put the Supplemental Agreement to a vote in the oil committee the following month, his colleagues rejected it unanimously, despite Anglo-Iranian’s efforts to bribe them. When, in the final days of December 1950, the ratification bill reached the Majlis and the new, pro-British, finance minister produced some figures to support his argument that the Majlis should vote to approve the deal, a National Front deputy interrupted him to accuse him of being in Anglo-Iranian’s pocket, since the oil company had been touting exactly the same numbers around the newspapers, saying that it would pay them to print them.

Mohammed Mosaddeq called for the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry. He “did not care about dollars, cents or numbers of barrels per day,” wrote one official. “He saw the basic issue as one of national sovereignty.”

Chastened by this exchange, Razmara withdrew the bill proposing the ratification of the Supplemental Agreement the same day. In January 1951, just after Aramco had announced that it had reached a fifty-fifty deal with the Saudi government, Mosaddeq took his argument to its logical conclusion and called for the nationalization of the company.

ANGLO-IRANIAN’S INITIAL RESPONSE to Mosaddeq’s demand was to do nothing. Its trenchant chairman Sir William Fraser stuck to the line that the company could not afford a fifty-fifty agreement, and the company’s misleadingly reassuring view was that the charismatic Iranian politician’s call was just a phase in the country’s kaleidoscopic politics. When one of the company’s most senior managers in Iran was asked in Whitehall what he made of the “the cry for nationalisation,” he replied that he “did not attach much importance to it.”5

Wrong as this analysis was, the unyielding attitude that it shaped was welcome to Ernest Bevin, who was simultaneously trying to fend off calls from Egyptian nationalists to evacuate British forces from their Suez base and was by now very ill. Reviewing the situation at the end of January, he described Mosaddeq’s call as “unrealistic,” dismissed the National Front’s influence as “undue,” and told his colleagues that they must stick to their existing policy. Accepting the company’s and his own officials’ view that the dispute could be resolved by money, he argued that they should continue to support the Iranian prime minister Ali Razmara in his efforts to push the Supplementary Agreement through parliament, since once that had happened, Anglo-Iranian would release the cash that it had promised under the 1949 deal.6

No sooner had Bevin given this assessment than an event in Tehran forced both Razmara and Anglo-Iranian into a rethink. Days later a leading ayatollah, Abol-Ghasem Kashani, organized a public meeting in support of nationalization in front of the Shah Mosque—the main mosque in Tehran’s bazaar. “A shriveled little Moslem mullah,” according to one newspaper, Kashani nursed an almost psychopathic hatred of the British. His father had been killed in battle with them in Iraq in 1914; as a vocal supporter of the Ottoman jihad, he had been interned by them after they invaded Iran in 1941. He had since capitalized on his treatment to shake donations from pious fellow countrymen, which he then disbursed to build a vast network of clients, many of whom worked in the bazaar where the meeting was taking place. Kashani called them the Society of Muslim Mujahids; the American ambassador described them as “a well-paid gang of professional hoodlums.” The ayatollah was implicated in several murders.7

Kashani was both an ally and a rival of Mosaddeq, since his goal was to take over the nationalization movement—an ambition that the British and Americans would eventually successfully exploit. For the time being, however, Mosaddeq and the mullah needed each other. While the wily politician won support from secular-minded, middle-class Iranians, it was the theatrical ayatollah who could whip up the devout. The Shah Mosque meeting at the end of January drew a crowd of about ten thousand people, who listened to a series of National Front politicians and mullahs calling for nationalization and, by way of a finale, another ayatollah who issued a fatwa stating that the Prophet had condemned a government that had given away its people’s inheritance to foreigners and so turned them into slaves.8

Both Razmara and the company appreciated that the fatwa represented a significant new departure. When the prime minister, who was alarmed by this barely veiled threat, now asked Anglo-Iranian if it would offer a fifty-fifty agreement, the company said that it would be willing to consider it. On February 23, the British ambassador reluctantly confirmed that the British government was also “ready to examine an arrangement on a 50-50 basis,” provided the Iranian government stood up against nationalization.9

Since open acceptance of this offer would only fuel allegations that he was in the company’s pocket, Razmara preferred to keep the ambassador’s offer secret so that he could appear to wring it from the British later on. Instead, fatally, he decided to argue that nationalization would be disastrous because Iran lacked the expertise and the resources to operate its oil industry independently. It would also be illegal.

Four days after Razmara tried out this argument on the oil committee, he was shot dead outside the Shah Mosque, where the fatwa had been issued a few weeks earlier. On the day after his assassination, Mosaddeq’s Oil Committee unanimously voted in favor of nationalizing Anglo-Iranian and referred the matter back to the Majlis for a vote. Showing an uncharacteristic independent mindedness, Iran’s deputies shrugged off British pressure on them to stay away so that the session was not quorate and voted for nationalization on March 15, 1951. “The situation in Persia has taken an unfortunate turn,” Britain’s Joint Intelligence Committee observed the same day, from London.10

The British government decided that, if the current Majlis would not do as it was told, the time had come to dissolve it and elect a new one—a strategy that hinged on the complicity of the shah. But by the time they had decided on this course of action, the American diplomat George McGhee had established that it was not viable. As soon as he received news of the Majlis’s vote for nationalization, McGhee had raced to Tehran, where he found the young shah in his palace lounging on a sofa. When he told him that he would have British and American support if he opposed nationalization, the shah “said he couldn’t do it. He pleaded that we not ask him to do it. He couldn’t even form a government.” To McGhee he looked “a dejected, almost broken, man.” A British diplomat’s verdict was harsher: “He has no moral courage and succumbs easily to fear.” In fact, he suffered from depression.11

From Tehran McGhee headed again to London for further meetings with the British. Desperate to avoid nationalization because it might give the Saudis ideas, he suggested that Anglo-Iranian could rescue the situation by making the Iranians an offer on a par with Aramco’s to the Saudis. But it was crucial that Anglo-Iranian not reach a more generous settlement with the Iranians because that would be sure to trigger renewed Saudi pressure on Aramco.

The problem was that differences between the companies’ structures and in their treatment under their respective tax systems meant that what McGhee was proposing was almost impossible to achieve in practice. In particular there was no way that the British government would extend to Anglo-Iranian the same foreign tax relief that had enabled Aramco to offer the Saudis a new deal at no cost to itself because the British regarded their company as a cash cow. “It might be best,” McGhee admitted, after he had mulled over the challenge at length, “not to attempt to clarify the complex issue of whether the 50-50 split is before or after the taxes of the country in which the company is domiciled… let each company work out with the country concerned what the 50-50 arrangement actually means in practice.” In other words, he was proposing a fudge.12

To pay lip service to the fifty-fifty concept, McGhee suggested that the Iranians might take back control of their resources and enter an agreement in which Anglo-Iranian would operate production and split the resulting profits with the country. As Bevin was by now on his deathbed, the American diplomat put this idea to Bevin’s unimpressive successor at the Foreign Office, Herbert Morrison. Even allowing for the fact that Morrison was new to the job, his ignorance was glaring. “Ernie Bevin didn’t know how to pronounce the names of the places either,” said one man, after Morrison got in a tangle over the word Euphrates, “but at least he knew where they were.” The meeting went badly after Morrison decided that McGhee had probably already tested his proposal on the Iranians during his visit to Tehran. “McGhee’s approach to some of our Middle East problems struck me as being a little light-hearted,” the new foreign secretary reported to his colleagues in the cabinet and the embassy in Washington afterward. “I told him to be careful.”13

McGhee’s lunch with the chairman of Anglo-Iranian, Sir William Fraser, did not go any better. Like McGhee, the Scotsman understood the technical side of the oil business perfectly, but there the similarity ended. While McGhee was young and genial, Fraser was dour and dictatorial, and when another British official said that Anglo-Iranian though “technically highly competent… had as much political nous as a blind rhinoceros,” he undoubtedly had the company’s chairman in mind.14

Fraser had been working in the oil business longer than McGhee had been alive and, “a Scotsman to his fingertips” to quote one of his colleagues, he viewed everything with an eye to how his shareholders might react to it. Their returns had already been squeezed by the ailing Labour government’s policy of dividend restraint, and Fraser was probably looking forward to being able to be more generous if, as was expected, the Conservatives were soon back in power. When he heard McGhee’s scheme, he gave it short shrift because he could immediately see that it would eat into the profit he could distribute in dividends. “The trouble with you, McGhee, is that you are operating on the basis of the wrong information,” he remarked. “Fifty-fifty is a fine slogan, but it seems to me to be of dubious practicality.”15

McGhee must have recognized the truth in what Fraser was saying, but equally he thought that a deal was urgently needed. On his return to Washington, he saw a CIA estimate that reckoned that, if the current situation persisted, Iran was “likely in time to become a second Czechoslovakia,” and so he saw the British ambassador again. Since one obstacle to nationalization was the fact that the Iranians could not afford to compensate the company’s current shareholders, he suggested that the British simply waive that right in exchange for half the profits. The ambassador, who in a previous life had taught McGhee at Oxford, took umbrage at the way in which his former student seemed to have accepted nationalization as a fact. The British government would be opposed, he said, “to any course which would represent straight appeasement to the pressures that had been created.” In London Herbert Morrison, who later characterized the exchange as “not altogether smooth,” continued to hold out for a solution that preserved British control over the company.16

MUCH AS MCGHEE may have wished otherwise, the reality, by April 1951, was that the British government had no room to maneuver. The election the previous February had cut its majority to five, and the difficult decisions that it was forced to make that spring ahead of the budget would spark a civil war inside the cabinet that eventually consumed the wider party. Nor was the sense of malaise that now seemed to surround the government simply metaphorical. Bevin died on April 14, and when Attlee heard the news, he was in the hospital himself, recuperating after an operation on a stomach ulcer.

The last thing that the convalescing British prime minister needed at this moment was a foreign policy crisis, but it looked alarmingly like one was brewing. Since Mosaddeq’s demand at the beginning of the year, the nationalists in Egypt had started talking about taking back the Suez Canal. To Attlee it was obvious that to cave in to the Iranian demand for the nationalization of the oil company would establish a “dangerous principle” that would not only deny the government a vital source of revenue but also ask for trouble in Egypt.17 Churchill, now leader of the opposition, could be expected to make hay out of both.

News from Tehran provided Attlee and his new foreign secretary Herbert Morrison with an excuse to hold out. From the Iranian capital, the British ambassador reported his belief that the National Front was “becoming apprehensive about the possible results of their… policy” and might yet be persuaded to come to an agreement. He also reckoned that the Iranians would welcome a strong lead from Britain and that action should be urgently taken to anticipate a likely investigation by Mosaddeq’s committee of the practicability of nationalization.18

This wishful assessment led the British government to make an unforced, pivotal error that, in hindsight, made the situation irretrievable. On April 27, after Mosaddeq pushed a more detailed resolution through the oil committee setting out the framework for nationalization, the Iranian prime minister resigned in protest. The British ambassador, who had heard that Mosaddeq realized his own proposals were unworkable, now pounced on what he saw as an opportunity to call his bluff. Hoping to install a pro-British candidate as the new premier, he encouraged another leading deputy to propose Mosaddeq for the top job. He was calculating that Mosaddeq would refuse, opening the way for Britain’s man.

Mosaddeq, however, saw the trap and accepted the challenge. After the Majlis endorsed him by a large majority, he in turn saw his chance to solicit general acceptance of his plan. He said that he would only assume the premiership if the Majlis also endorsed his oil committee’s resolution nationalizing Anglo-Iranian. After the Majlis did so unanimously, on April 29, 1951, Mosaddeq became prime minister. In cabinet the following day, Morrison decried what had happened as “a monstrous injustice”; the minister of fuel and power was rather closer to the mark when he reflected that it was “clear now that reports that there was no steam behind this were wrong.”19

Morrison now considered military action to seize Abadan and the oil fields: a plan drawn up by the military envisaged landing a force of seventy thousand men. An MI6 officer suborned the commander-in-chief of the garrison in the town nearest to Abadan, Khorramshahr, so that he would offer no resistance. Simultaneously, while claiming to be going shooting in the mountains, British embassy officials began talking to the chiefs of the Bakhtiari and Qashqai tribes, in whose territory the oil wells were situated. This did not escape the notice of the CIA, which speculated that the tribes might unilaterally declare their independence, creating a congenial environment that would allow “the exploitation of Iranian oil to continue under British management.”20

“Sheer madness” was Dean Acheson’s reaction when he learned about the British plan, and he quickly called on the British and Iranians to negotiate. His statement, released on May 18, was a model of evenhandedness. It sympathized with the Iranian decision, telling the British that Iran needed greater control over its oil resources, and warned the Iranians that a unilateral cancellation of the contract would have serious effects.21

Acheson’s intervention was the first sign that the United States was not going to side with London in the dispute, and its tone ruffled feathers in London: it was “as if we were two Balkan countries being lectured in 1911 by Sir Edward Grey,” huffed one Tory politician. But it had the desired effect. Attlee and Morrison shelved their plan to take over southern Iran and decided instead to refer Iran’s breach of contract to the International Court of Justice. And, most important, Morrison finally conceded in public that the government was now “prepared to consider a settlement which would involve some form of nationalisation.”22

Under American pressure, the British government had made an enormous concession, which then led to naught. At a meeting in Tehran with the British and American ambassadors two days later, Mosaddeq rejected the offer of talks with the British government. When the American ambassador, already annoyed by the Iranian prime minister’s repetitive “emotional and generally irrelevant references to the misery and poverty of his country,” then asked him if he had considered how he would operate the oil fields without British help, Mosaddeq was fatalistic. “Tant pis pour nous. Too bad for us,” he answered. “If the industry collapses and no money comes and disorder and communism follow, it will be your fault entirely.”23

The result of this meeting shaped Attlee’s chilly response to Truman when he received a letter from the president a few days later claiming that, since the Iranians were “willing and even anxious to work out an arrangement,” it was vital that negotiations “be entered at once.” When British officials found out that a copy of this letter had also found its way to Mosaddeq—supposedly by accident—they were incandescent, since it confirmed their suspicions of American bias. When a delegation from the oil company, which had arrived in Tehran for talks, was then confronted with an exorbitant Iranian demand and went home empty-handed ten days later, they blamed the president.24

ON JUNE 11, 1951, Iranian officials took control of the company’s main office in Khorramshahr, near Abadan. When the Iranians then insisted that tankers leaving Abadan should provide receipts for the oil that they were taking—a procedure that implied the oil was theirs and did not belong to the company—Anglo-Iranian’s general manager Eric Drake refused. The loading of tankers in the port stopped. The Iranians owned no tankers of their own and, annoyed by this development, proposed a new law making sabotage of the oil industry a capital offence. Fearing for his life, Drake fled to Basra, and on June 25 Attlee insisted that the remaining tankers at the port withdraw.

Attlee and his colleagues understood the implications of this move. As Hugh Gaitskell put it: “Our policy is to get the Persians into the position of getting themselves in a mess.” With no tankers drawing oil, Abadan’s fuel tanks would rapidly fill up. Once they had done so, the company would have to cap its wells and stop paying its eighty-thousand-strong local workforce. When that happened, the chances of rioting would leap: disorder would give the British grounds to send in troops in order to protect British subjects. Asked in the cabinet what he expected to come of this chain of events, Attlee said: “A reasonable Government, with which we could conclude a new agreement.”25

Aware of what the British government was trying to do, Truman bought time by dispatching Averill Harriman to meet Mosaddeq. Harriman, a former ambassador to London, enjoyed a reputation as a troubleshooter and, despite becoming exasperated by the Iranian prime minister’s erratic behavior, produced the verdict the president desired. “It is my impression that an atmosphere exists in Tehran today in which the British can make a satisfactory settlement,” he concluded after a fortnight in the capital, “I doubt whether as favorable a situation will present itself again.”26

Harriman’s optimism left the British with no choice but to send out a junior minister, Richard Stokes, to investigate the opening that the American had supposedly identified. When Stokes met Mosaddeq, the Iranian prime minister told him that his government had “divorced the company.” “It was a curious arrangement for a man to divorce his wife and then attempt to starve her to the point where she is obliged to kill him,” was the British minister’s disconcerting reply. Stokes would only offer a deal that left Anglo-Iranian substantially in control of oil operations, and after almost three weeks in the country, he too left Tehran empty-handed. He realized that the window for a negotiated settlement had already closed. “Fifty-fifty won’t do in Persia,” he reported after his return, “because they’ve had a worse basis for so long.”27

The matter was still unresolved when Attlee called an election that September. In what turned out to be his final cabinet meeting, he and his colleagues reviewed the situation one last time. Having heard the news of the election, Mosaddeq had just announced that he would expel the British technicians working at Abadan on October 4, the date of the British Parliament’s dissolution. The deliberate timing of this move left Morrison splenetic. “The Persians tear up the contract without consultation with us. Push our people around. Steal their personal property. Pinch British asset,” he railed to his colleagues. Now they “propose to push British personnel out.” The foreign secretary still favored the use of force, but Attlee did not. Although he was well aware that such a move would be very popular, he knew that he lacked Truman’s support to take it and, thinking it anyway unlikely to succeed, preferred to refer the matter to the Security Council. He was backed by his colleague Hugh Dalton. “We can’t flout the United States, on whose aid we depend so much,” was the former chancellor’s matter-of-fact observation.28

After the British ambassador to the UN broached the issue on October 1, 1951, his Iranian counterpart asked for time, to enable Mosaddeq to come to New York to speak. “The British give me the impression of singing the last act of ‘The Twilight of the Gods’ in a burning theater,” observed America’s ambassador to the United Nations, after he had heard his ally speak. An MI6 officer was blunter still. “In the last crucial days there was nobody at the helm.”29

A change of government now looked almost certain. The Conservatives were some way ahead in the polls, while Attlee looked “tired and rather disillusioned,” American diplomats reported from London. Their impression was that the Labour Party seemed “willing to give up office at the present time… but with the hope that they will come back… in the not too distant future following the failure of the Conservatives to solve the present world-wide problems which they would inherit from Mr Attlee’s Government.”30

Mohammed Mosaddeq was not so sure. He had come to New York to represent his country at the United Nations, and George McGhee was keen to keep him there, hoping that it might be possible to broker a rapid solution with the new British government. When he met McGhee on October 28, after it was clear that the Conservatives had narrowly won, he admitted to being “somewhat disquieted” by the outcome because he feared that Churchill would turn out to be “more intransigent” than Attlee. Although McGhee tried to convince him otherwise, he was entirely right to be.31