‘Worse than the Loch Ness monster’: menstruation and menopause

The myths and taboos around menstruation are of biblical proportions. Take this from Leviticus, the third book of the Old Testament and Torah: ‘If a woman have an issue, and her issue in her flesh be blood, she shall be put apart seven days: and whosoever toucheth her shall be unclean until the even’ (Leviticus 15:19).

Strong myths around cleanliness for centuries have prevented menstruating women from preparing food, having sex, visiting places of religious worship and even entering the home. These myths are often fortified by social taboos that prevent women from talking about their menstrual cycles, and cultural prescriptions about which menstrual hygiene products are acceptable for women to use. In India, for example, in some states it was believed a woman would go blind or never get married if she used sanitary pads; instead, rural women used leaves, ash, sawdust and old rags—which they couldn’t dry in the sun so were never disinfected.1 A lack of access to any kind of menstrual hygiene products or private toilet facilities still prevents millions of girls around the world from attending school each month. This isn’t just bad for their education, limiting their life opportunities, it’s also bad for their health: in India, 70 per cent of all reproductive illnesses are caused by poor menstrual hygiene.2 It can also affect maternal mortality.

And if you think this isn’t a problem in the Western world, consider the Australian Aboriginal woman who was fined $500 for stealing a $6.75 packet of tampons from an outback service station. She said she stole them for someone else who was ‘too ashamed’ to buy them herself.3

Meanwhile, UK food banks have reported an increase in demand for sanitary products, with reports of people using toilet paper and staying at home during their periods, or stuffing socks and newspaper in their underwear. The problem is so large-scale that Scotland piloted a free sanitary products scheme in 2018, which it expanded in 2019.4

In June 2018, Labour MP Danielle Rowley stood up in the British House of Commons to announce she had her period and it has cost her £25 (A$45) that week already. ‘You know the average cost of a period in the UK over a year is £500. Many women can’t afford this. What is the minister doing to address period poverty?’ she asked. Back in 2000, the UK Labour government had reduced the sales tax (VAT) on sanitary products from 17.5 to 5 per cent but said it couldn’t reduce it any further under European Union rules. In response to Rowley, the minister for women, Victoria Atkins, promised to remove sales tax on menstrual products once the UK’s exit from the EU was final, and said her government was ‘watching with interest’ the Scottish government’s program to deliver free products to those in need.5

In October 2018, Australia finally caught up with much of the US in dropping the sales tax on menstrual hygiene products. We’ve seen how lack of access to menstrual products holds girls back from school and women from work; we know lack of access to hygienic products causes disease and illness. Yet for two decades the Australian government refused to lift the sales tax on these products despite the loud demands of feminists. While a policy to lift the tax was briefly flirted with in 2015, the government later reneged, as did the Opposition Labor Party, which claimed it ‘couldn’t afford to lose the revenue’.6 Women earn 17.9 per cent less than men in Australia. Women do the bulk of unpaid labour, such as cooking, cleaning and housework, with Australian women being among the most overworked in the world. Australian women retire with 53 per cent of the superannuation that men retire with and are significantly more likely to experience poverty than men. And the government needs more revenue from us?

As New York governor Andrew Cuomo noted upon repealing the state sales tax on menstruation products in 2016, removing these taxes is a ‘matter of social and economic justice’.7

But it’s not only cost and access holding women back. In almost every country, myths around menstruation continue to prosper and a tampon falling out of a handbag remains a sadly embarrassing event. The period-tracking app, Clue, compiled a list of 36 superstitions about periods from around the world: avoiding cooking, washing hair, having sex, swimming or taking a bath are common superstitions across cultures and continents. Tom Rankin, a program manager supporting water, sanitation and hygiene projects for the human rights agency Plan International Australia, told me that in parts of eastern Africa, menstruating women aren’t allowed to cook or fetch water: ‘There’s all these myths, like if you milk a cow, the cow will go dry. Or if you tend a garden, the garden will be unproductive. Or if you walk over water pipes, it contaminates the water,’ he said. ‘All these … myths that relate to menstruation create these enormous social barriers for women and girls just to participate freely in society.’

Medical science has played a historic role in perpetuating ideas that menstruation is unsafe, unclean and unmentionable. We’ll see in the next chapter, on hysteria, how women’s reproductive functions have been pathologised and suspected throughout history, and used to justify women’s limited role in society. Dr Kate Young, a public health researcher at Monash University, has highlighted how even today medicine ‘endorses menstruation as a leakage that transgresses bodily boundaries, supposedly evidencing women’s inherent lack of control over their bodies and reinforcing their “need” to remain in the private sphere’.8

Such myths thrive in a culture of silence, where whispers that enforce unscientific practices go unchallenged because the taboo of talking about menstruation reigns supreme over education and facts. In the US, an ad was banned from the New York subway because ‘of the nature of the language used’. ‘Underwear for women with periods’, was the offending sentence. As Deirdre Hynds noted in the Irish Times,9 at the time the ad was banned in 2015 the city’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority had seen fit to approve ads for ‘breast augmentation’ and a photo of a woman being choked with a necktie in an ad for a Fifty Shades of Grey film.

Making talk of periods shameful is a key strategy in the oppression of women worldwide—and it happens in every modern society. But the menstrual cycle, and changes to it, are signs of so much regarding the health of everyone who menstruates.

The American actress Courteney Cox was the first person to say ‘period’ on television—that was in 1985 in a Tampax commercial, and it hasn’t been said much since. In its work with girls around the world, Plan International has found that menstruation must be discussed at a community level if stigmas are to be broken down. The greatest success is seen when men and boys become actively involved in the conversation, because men are often the enforcers of social stigmas and cultural norms. This isn’t so different in the Western world, which is why campaigners in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom have all told me how imperative it is to teach boys about all aspects of menstruation—including what’s a normal amount of period pain—in schools. Only when menstruation stops being secret women’s business will life improve for everyone who struggles to enjoy full dignity and social inclusion when they have their period. Some health campaigners want menstruation to be taught in health lessons, separate from sex education, because of the shame and stigma involved when it comes to sex. Indeed, separating health from sex and gender issues remains a massive hurdle to overcome.

Our menstrual cycle can be a key clue to our health, so noticing when things change is important, as is being able to confidently talk about our cycle to healthcare professionals. Knowing the facts is also the single biggest threat to the survival of dangerous and repressive myths.

We need to know what’s normal as opposed to what’s common. Period pain is common; period pain that interferes with daily life isn’t normal and should be investigated. Bleeding between periods is common, but it isn’t necessarily normal and should be reported to a doctor. The Eve Appeal found that almost 20 per cent of women wouldn’t report abnormal bleeding to a doctor—a disturbingly high figure, and one that needs to change. A strong social conditioning in people who menstruate makes us not want to be ‘difficult’, and maybe some don’t know if abnormal bleeding is a cause for concern.

We must destroy the taboo on talking about periods. It’s not only education that needs to change, it’s conversation.

But first: facts.

THIS IS HOW YOUR MENSTRUAL CYCLE WORKS

From puberty to menopause, menstrual cycles begin and end on the first day of the period. Cycle lengths vary from woman to woman, and from culture to culture. For most Western women, the average cycle is about 28 days but anything from 23 to 35 days is normal. Most fluctuate slightly from cycle to cycle and throughout reproductive life, though some lucky ducks have a stickler cycle that turns up on the same day each time. If only! Mine ranges from 24 to 35 days, and I never know which I’m gonna get.

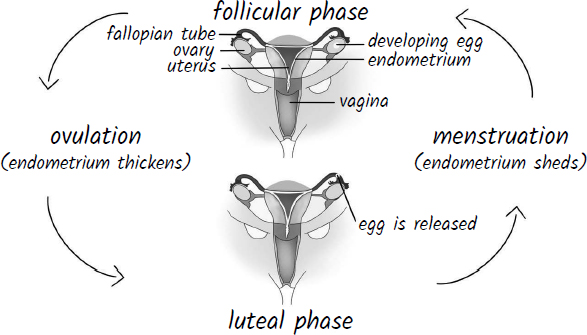

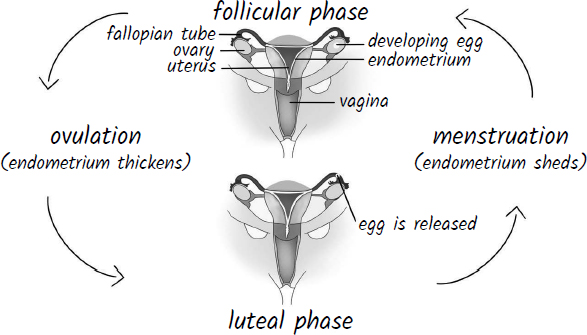

The menstrual cycle

The menstrual cycle is divided into two phases: the follicular (the first) and the luteal (the second). The follicular phase varies in length but the luteal phase is almost always 14 days long. So, if a cycle is 28 days long, the follicular phase will be 14 days and the luteal phase will be 14 days. If a cycle is 35 days long, the follicular phase will be 21 days and the luteal phase will be 14 days. If the cycle is 23 days long, the follicular phase will be nine days and the luteal phase will be 14 days. There are some exceptions, but even then the length of the luteal phase won’t change throughout the reproductive years.

The follicular phase

Day one of the follicular phase is when bleeding begins.

Remember follicles? They’re the cellular sacs in which eggs wait to mature. During the first phase of the menstrual cycle these follicles develop, preparing multiple eggs for ovulation.

Throughout the follicular phase, oestrogen is the dominant hormone. On day one, when the uterus is busy getting rid of the lining it doesn’t need (no egg has been fertilised), both oestrogen and progesterone levels are low. This alerts the pituitary gland in the brain—part of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis—to start producing something called follicle-stimulating hormone to … you guessed it, stimulate the follicles to start maturing those eggs.

At around day seven, if you have an internal ultrasound you can usually start to see a number of follicles developing in each ovary. They could be up to 6 to 7 millimetres at this stage. As they grow the follicles produce oestrogen, and the bigger they get the more oestrogen they produce; this causes the uterine lining to grow in preparation for the implantation of a fertilised egg. Over a number of days, one follicle will usually become dominant. When it reaches around 18 to 20 millimetres in diameter, oestrogen levels are so high that it sends a signal to the pituitary gland to produce luteinising hormone, which activates the egg so it’s ready for the fertilisation process, then releases it from the ovary.

This point marks ovulation, and the beginning of second phase of the menstrual cycle.

The luteal phase

In the second phase of the menstrual cycle, the egg goes in search of a partner in the form of sperm.

Once released, the egg survives for a maximum of 24 hours. Hard to believe, isn’t it? All that hard work developing, it wins the battle of the ovum, then it only lives for a day! But textbooks have wrongly presented sperm as the go-getting gamete that hunts down and pierces the waiting egg. As Emily Martin laid bare in her 1991 paper, ‘The egg and the sperm: How science has constructed a romance based on stereotypical male-female roles’,10 the egg is far from passive. Martin found that even though several biologists have confirmed the egg plays an active role in attracting and capturing semen—while semen is quite weak and slippery, incapable of implanting without the egg’s participation—textbooks and other learning materials have continued to use language that centres the sperm as active and the egg as passive. ‘The imagery keeps alive some of the hoariest old stereotypes about damsels in distress and their strong male rescuers,’ wrote Martin. ‘That these stereotypes are now being written in at the level of the cell constitutes a powerful move to make them seem so natural as to be beyond alteration.’

Once released the egg goes in search of sperm, which has often been bumbling around the fallopian tubes for hours or even days. As the eager egg bobs along the tube and the sperm wait, progesterone takes charge. When a follicle releases an egg, it breaks down and becomes the corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. In the follicular phase, oestrogen helped build up the endometrium in the uterus; now, progesterone takes the lead role in maintaining it to make sure it’s a welcoming environment for a fertilised egg. While progesterone is on the rise, it prevents the uterus from contracting to expel the endometrium. It also tells the pituitary gland not to produce follicle-stimulating and luteinising hormones so that new eggs aren’t developing while our activated egg is on the prowl for a partner.

If the egg isn’t fertilised, the corpus luteum dies out and stops producing progesterone. With progesterone levels plummeting, the endometrium stops thickening, and the uterus can contract and expel its lining. The pituitary gland can now produce its hormones again, so follicles begin to develop and the cycle restarts.

PREGNANCY

If a fertilised egg implants in the endometrium, a hormone called human chorionic gonadotropin is produced. This tells the corpus luteum to keep producing progesterone, along with a type of oestrogen; the progesterone prevents menstruation and continues to make sure the endometrium is a nourishing environment for an embryo. The corpus luteum maintains this role until about week eight of pregnancy, when the placenta takes over and the corpus luteum dies out. So the human chorionic gonadotropin determines whether the corpus luteum lives or dies, and therefore whether you menstruate—that’s why this is the hormone that pregnancy tests look for.

Something happens to a lot of people when they start trying to become pregnant. Many of us have spent a good portion of our adult lives stressing about accessing the morning-after pill, waiting anxiously for our periods to arrive, and worrying about broken condoms, missed pills, a bout of vomiting or diarrhoea—and then one day, all this is turned on its head and we start dreading our periods. We’re back to playing close attention to our cycles but for the opposite reasons. Then we discover that an egg only lives for a day, and we’re like, OHMYGOD, what the hell?! How many times did I needlessly get the morning-after pill? How many months did I waste worrying whether I was pregnant when I had sex at a time when it was next to impossible?

Here are a few relevant facts about fertility:

• It can take sperm cells anywhere from 45 minutes to 12 hours to reach the fallopian tubes, and they can survive there for up to seven days, although normally it’s about 48 hours.

• Even though millions of sperm may be ejaculated at orgasm, only a few dozen make it all the way to the fallopian tubes.

• As we saw in the previous chapter, the cervix is closed for most of the menstrual cycle, but around the time of ovulation its thick mucous plug thins to allow sperm into the uterus.

So when are you fertile?

A study of 221 healthy women looking into the timing of sexual intercourse found nearly all pregnancies resulted from intercourse in the five days before ovulation and on the day of ovulation. That would mean we’re only fertile for six days per cycle.11

The egg and sperm fertilising in the fallopian tube doesn’t equal pregnancy. There are still many, many barriers to overcome before that happens. Pregnancy only occurs when an embryo embeds in the endometrium—and this usually takes about seven days. The process fascinates me; when I was undergoing IVF, I’d stay up late into the night reading brochures and articles about it. During fertilisation, a single cell is created called a zygote, which keeps dividing into more cells roughly every 24 hours. By day five, it will have become a blastocyst, containing between 75 and 100 cells. At around day seven, the blastocyst implants in the uterine wall; this is when pregnancy begins and human chorionic gonadotropin is released.12

Between 30 and 70 per cent of zygotes don’t make it to implantation. Some researchers think this is because of genetic imperfections—it seems the body discards most genetically damaged fertilised cells before they become foetuses.

About 14 days after fertilisation and seven days of being snuggly embedded in the endometrium, the blastocyst becomes an embryo. This is also the stage at which most periods would usually be due. The embryo stage lasts until about week nine or ten, when it becomes a foetus.

PERIOD PAIN

Most girls, women and other people who menstruate get some amount of pain with their periods. But what is a normal amount of period pain? It’s important to understand this because so many people report being told ‘period pain is normal’ when they complain to a medical practitioner, or even just to their friends and family.

Period pain that interferes with daily life isn’t normal.

Dr Susan Evans, a gynaecologist, pain physician and chair of the Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia, tells me, ‘Normal period pain is pain on the first one to two days of bleeding that is easily managed with taking an anti-inflammatory or going on the pill.’

A number of factors could be causing period pain. One is a hormone called prostaglandins, produced by endometrial cells that form the uterine lining. When the endometrium is shed during menstruation, it releases a large amount of prostaglandins, causing the uterus to contract and expel its lining. Studies have shown that people with period pain have high levels of prostaglandins. The good news about this is that over-the-counter medicine known as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can block the production of prostaglandins and help to ease the pain: ibuprofen (Nurofen is one of the big brands that sell this), naproxen (Naprogesic or Naprosyn) and diclofenac (Voltaren) can all be bought in most supermarkets and pharmacies, and have all been shown to work for most cases of period pain. They’re more effective if taken before the pain starts or before the pain becomes severe. The Pelvic Pain Foundation of Australia has good information on how to take these drugs to manage or avoid pain.

Taking the contraceptive pill—one with more progestin (synthetic progesterone) than oestrogen—has also been proven to help manage period pain in most people, as has the Mirena intrauterine device (IUD). It’s important to avoid taking opioids, like Endone or OxyContin, to treat period pain where possible, because studies show that these drugs can make chronic pain worse.

If none of these methods reduce the pain and make life easier, another issue may be at play. Endometriosis, adenomyosis, fibroids and pelvic inflammatory disease are some of the main potential causes of pain that should be investigated by a doctor at this stage. However, it may just be that you have severe period pain and no other identifiable disease. Chronic pelvic pain is now being recognised as a condition in itself that should be taken seriously. I’ll talk a lot more about period pain and how it can lead to chronic pain conditions if untreated in Chapter 6. The important thing to remember here is that if period pain interferes with your daily life or happens on more than one to two days at the start of bleeding and can’t be controlled with over-the-counter drugs, it’s not normal and you should see a doctor.

PREMENSTRUAL SYNDROME

The neuroscience of looking at how oestrogen and progesterone influence mood is ‘so new it’s practically pre-pubertal’, writes the neuroscientist Dr Sarah McKay in The Women’s Brain Book.

Huh? Don’t all women occasionally become emotional and irrational before they get their period? Haven’t some women been acquitted of murder because of premenstrual stress? When you really lose your shit at your loved ones, don’t you just know it must almost be that time of the month?

Well, no, yes and no. It’s true that two British court cases in the early 1980s established PMS as a defence for murder but, as McKay notes, no study has ever shown that women’s ability to think clearly is influenced by their menstrual cycle. And despite the best efforts of some male scientists, no one has been able to prove that men are naturally more intelligent than women. ‘This is good news!’ writes McKay. ‘Our cognitive abilities and intelligence are not held captive by hormones.’13

This isn’t to say that PMS doesn’t exist. Many women report some physical or psychological symptoms in the days before their period, although numbers vary widely and more research needs to be done on this topic (surprise, surprise). Physical symptoms commonly include tender breasts, bloating, headaches and greasy hair or skin. Mental symptoms include mood swings, anger, irritability, fatigue and foggy thinking. Some women with migraines or autoimmune conditions report their usual symptoms getting worse in the days before menstruation.

But this syndrome has blurry edges, in that literally hundreds of symptoms can be ascribed to it. The narrative of PMS embedded in Western culture is based more on folklore than science. There’s no widely accepted figure for the number of people who experience it, although the US Office on Women’s Health says that more than 90 per cent of women will have some symptoms in the days preceding their periods, such as bloating, headaches and moodiness, while fewer than 5 per cent suffer the severe symptoms of another condition, premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Other studies claim that between 20 and 30 per cent of women suffer mild to moderate symptoms of PMS.14

One of the main reasons patriarchy is so successful is that it has established countless ways for women to blame ourselves for our own oppression. Girls are taught from a young age to police themselves as they try to meet society’s expectations of femininity. While trying to be ‘good’, most women have pinned a bad mood to their menstrual cycle at one point or another. We’ve probably been insulted by someone who blamed PMS for the fact we’re angry at them—and we may have agreed, blaming ourselves too. The idea of the menstrual cycle turning women into harridans is so entrenched in our society, as women we even buy into it ourselves. And when losing our temper happens to coincide with the premenstrual phase, we notice this and blame it on the hormones.

But this is a phenomenon called confirmation bias: we’ve heard about PMS our whole lives, so when we act in a way that fits the narrative, we accept it as truth.

Numerous studies have called into question the most damaging fictions about PMS: those that attribute anger and irritation to uncontrollable female hormones. Sarah Romans, a professor of psychological medicine at the University of Otago in New Zealand, has conducted two studies that show mood swings in women rarely correlate to the premenstrual phase. Her Mood in Daily Life study, which looked at nearly 80 Canadian women who kept a daily mood diary over six months, ‘found little evidence to support that premenstrual phase by itself influenced mood. Instead, mood was more closely influenced by one of three culprits—lack of social support, perceived stress or poor physical health.’15 In a separate literature review Romans conducted, she found no clear evidence of the existence of a specific premenstrual negative mood syndrome in the general population. ‘This puzzlingly widespread belief needs challenging, as it perpetuates negative concepts linking female reproduction with negative emotionality,’ she wrote.16

Jane Ussher, a professor of women’s health psychology at Western Sydney University, documents in her fascinating 2006 book, Managing the Monstrous Feminine, that most of the psychological symptoms women put down to PMS were reactions to stresses in their lives that they silenced for the rest of the month. Across the 70 women interviewed in Australia and the UK, it was startling to observe the similarities in the causes of emotional outbursts attributed to PMS. Many spoke of the lack of support they received from their male partners, of being overwhelmed by the burden of housework and childcare, and being taken for granted by their families. Women with less of an overwhelming burden, and those who had supportive partners, tended to fare better.

In her book, Ussher speaks of the premenstrual phase as a time of vulnerability in some women, saying those who usually repress their anger or resentment at partners, children or the unfair burden of their responsibilities are more likely to let it erupt at this time. ‘So the body, that old stalwart source of sin, is positioned as to blame. Don’t blame men, or families, or the impossible constraints of femininity for the rage, for the frustration at lack of support or space. Blame raging hormones.’17

So the take-out is this: some women become more sensitive and irritable premenstrually, and a minority have a severe reaction. But this doesn’t impair their ability to think or work, or make them somehow out of control—their anger is usually in response to real life stress.

Throughout history, women’s reproductive organs and so-called raging hormones have been used as excuses for their exclusion from education, professional work and public space. If we are to accept that women are essentially out of control for one week in every four, then perhaps the ban on female pilots should be reinstated? Or, as Ussher suggests, what’s stopping legislators from preventing women from driving cars in their premenstrual phase? (Perhaps the fact that women have fewer accidents than men, no matter what part of the cycle they’re in?)

A person’s lived experience should never be denied, and treatment should of course be provided for those who suffer physical or mental distress, whether or not it’s cyclical. As in most areas of women’s health, not enough is known about premenstrual syndrome. What is definitively known is that the normal variation in hormones throughout the menstrual cycle does not cause someone to be irrational, unreasonable or totally lose control.

MENOPAUSE

Just like menstruation, menopause is a natural cycle of life that’s also a highly charged social construction. Both are dogged by taboos, shame, lack of education and misinformation.

There’s an Amy Schumer comedy sketch in which she comes across the actors Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Tina Fey and Patricia Arquette having a picnic in the woods. They tell her they’re celebrating Louis-Dreyfus’s ‘last fuckable day’. ‘In every actress’s life, the media decides when you finally reach the point where you’re not believably fuckable anymore,’ Louis-Dreyfus explains to Schumer.

The sketch instantly became a classic, not only because it feels so true about media and Hollywood, but also because this is how many women approach menopause. It’s as though this change in their lives is the end of themselves as attractive, sexual beings. And that’s because it has historically, at least in the Western world, been sold that way by some doctors and scientists.

Two seminal books helped establish this idea in Western society at a time when women were finally starting to gain some freedom. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask), by the psychiatrist Dr David Reuben, is one of the biggest-selling books on sex of all time and later inspired a Woody Allen movie of the same name. Published in 1969, it had a profound effect on sex education and has been hailed as an integral part of the sexual revolution. It included such gems on menopausal women as: ‘Having outlived their ovaries, they may have outlived their usefulness as human beings. The remaining years may be just marking time until they follow their glands into oblivion.’18 And: ‘As estrogen is shut off, a woman comes as close as she can to being a man. Increased facial hair, deepened voice, obesity, and the decline of breasts and female genitalia all contribute to a masculine appearance. Coarsened features, enlargement of the clitoris and gradual baldness complete the picture. Not really a man, but no longer a functional woman, these individuals live in a world in intersex … sex no longer interests them.’19

Sex no longer interests them? Try telling that to the women in an Australian study20 who reported having a greater sex drive associated with a new partner following menopause. Reuben’s descriptions of menopausal women are pseudoscience, better known as bullshit. When it comes to menopause, there’s a lot of it around.

The American gynaecologist Dr Robert Wilson was instrumental in constructing menopause as a disease, one that could be cured by doctors with drugs. A paper he wrote with his wife, Thelma, in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society in 1963 was so influential, he expanded upon it in his bestselling 1966 book, Feminine Forever. He was evangelical about hormone replacement therapy (HRT)—while being paid by the pharmaceutical companies that produced it—and tried to justify his position with insults: ‘All post-menopausal women are castrates.’ But, he urged, if women took HRT, they could be ‘feminine forever’. He claimed that the benefits of HRT extended far beyond symptom relief, writing that a woman’s ‘breasts and genital organs will not shrivel’ on the therapy: ‘She will be much more pleasant to live with and will not become dull and unattractive.’21

It’s not just medical doctors who have pushed these grotesque notions on Western women about menopause. Academic researchers have made similarly repressive claims based on questionable science. The authors of one 2013 paper claim to have discovered that women go through menopause because men of all ages prefer younger women, so older women won’t be having sex and don’t need to reproduce.22

In her book, Inferior, the science journalist Angela Saini does a great job documenting the raging battle among evolutionary biologists over why human females go through menopause. What emerges is clear evidence that scientists, just like people everywhere, are influenced in their collection and interpretation of data by their life experience, beliefs, and—yes—their gender.

It’s important to note that the controversial paper claiming menopause exists because men don’t find older women attractive, from the evolutionary biologist Rama Singh and his colleagues at McMaster University in Canada,23 was published at a time when a growing body of evidence in evolutionary biology seemed to support the ‘grandmother theory’ of menopause. This theory supposes that women go through menopause because their role as grandmothers is integral in child survival, exploding myths about useless old ladies staring into oblivion and instead granting them centre stage in the survival of the human race. The American anthropologist Kristen Hawkes has spent decades collecting data to support this theory, and others have added to it. As Saini points out, when it comes to evolutionary theories on menopause, there’s a trend that isn’t hard to spot: ‘counter-theories to the grandmother hypothesis appear to come mainly from men’.24 Clearly, some of the men writing the science on sex and biology, and influencing how it’s taught, have certain ideas about women and certain interests in maintaining the status quo.

Most women experience some unpleasant effects of menopause, but the dread women hold about this process is at least in part socially constructed. No other expected life change besides death is approached with such fear and apprehension.

Of all the myths surrounding menopause, three stand out: a woman’s sex life is over, she’ll gain a lot of weight and she’ll turn into a maniac. None of these are certain to occur, and with knowledge and the right treatment all can be avoided or minimised. A 1992 study published in the Psychosomatic Medicine journal found that attitudes to menopause went some way in predicting experiences. ‘Middle-aged women believe that holding negative expectations about the menopause affects the quality of the menopausal experience. Indeed, that appears to be the case, perhaps because myths can function as self-fulfilling prophecy,’ wrote the study’s author, K.A. Matthews.25

In cultures where older women are revered and granted power, they report fewer menopause symptoms than in cultures where this doesn’t take place. This remains true in cultures as far apart as Rajasthan in India and in Indigenous communities in the Tiwi Islands, in northern Australia. Beverley Ayers, a psychologist from King’s College London, noted this discrepancy in an article for the Psychologist, showing that women in India, Japan and China experience far fewer menopause symptoms than those in the West.26

I’m not suggesting that magical thinking will make menopause a breeze. The process of ageing presents challenges to everyone’s bodies, and menopause has proven physical impacts. Sex hormones are fluctuating during this time, which can cause dramatic physical and mental effects in some women. Many of us remember how hard it was to go through puberty—facing it again, in reverse, doesn’t sound like much fun. But menopause doesn’t last forever, and not all women have a terrible experience. It’s not the end times—far from it. In the second season of the British sitcom Fleabag, a character played by Kristin Scott Thomas calls menopause ‘the most wonderful fucking thing in the world’. This seems like a good time to give menopause a makeover.

As with all subjects that have been taboo, changing minds and attitudes is hard. Many brave famous women, including Jean Kittson in Australia, Jane Fonda in the USA, Kirsty Wark in the UK, and Germaine Greer, Emma Thompson, Angelina Jolie and Gillian Anderson have started to speak about their experiences of menopause, but representations of older women or of menopause itself remain rare in Western culture—at least outside of comedy, where menopausal women are usually the butt of the joke.

After the release of the French film I Got Life!, about a menopausal woman, the English journalist Suzanne Moore lamented the lack of representation of menopause in popular culture. ‘As long as we don’t have any kind of representations of menopause, in all its glory, then it will continue to be seen as a sign that a woman is somehow redundant because she can no longer reproduce. If we were to talk more openly, we would find instead that many women feel liberated, full of energy, able to take on the world, and finally free from the demands of a society that values only youth. As the heroine of this movie kicks off her shoes, dances, gardens, makes love, becomes a grandmother and hangs out with her friends, life in its messy way continues. The idea that women may indeed be less concerned about how others see them and become more of themselves is a story rarely told,’ Moore wrote in The Guardian.27

Menopause cafes are popping up in workplaces all over Britain, ‘where co-workers gather over cake to compare notes about the way hot sweats, aphasia (language problems), insomnia, dry vaginas and how the ins and outs of HRT might affect women’s sense of wellbeing at work. Male colleagues wanting to better understand how to support their female partners are warmly welcomed,’ explained Marina Benjamin, author of The Middlepause.28 This development is worth applauding, and let’s hope the trend kicks off around the world.

But what exactly goes on during menopause?

The biology of menopause

Understanding the biology of what causes menopause is pretty easy when you have a basic grasp of the female reproductive system. What’s harder is understanding the effects, and how they relate to what’s happening biologically as well as socially and psychologically during menopause.

First: what is menopause? Medically, it’s when someone hasn’t had a period for 12 months. Commonly, we speak of ‘going through menopause’ but, strictly speaking, the time leading up to the end of periods is the perimenopause. Someone isn’t menopausal until 12 months since their last period. After that, they’re post-menopausal.

The average age to reach menopause is 51, although five years either side is considered normal. This is pretty standard around the world and isn’t affected by the number of pregnancies experienced or any hormonal contraception that’s been taken. Even the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle mentioned that women stopped having babies around the age of 40 to 50, so apparently the age of menopause hasn’t changed for millennia. It’s a natural part of the ageing process. Men also experience hormonal changes as they age, mainly involving a reduction in the production of testosterone, but the effects are generally not as sudden or dramatic as in menopause. Having said that, some people breeze through menopause without a hitch, while one in three men in their 50s will suffer serious side effects as their testosterone declines. In other words, the ageing process is an individual thing—we all experience it differently, whatever our gender.

Surgeries such as hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) and oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries), chemotherapy and radiotherapy to the pelvis can also cause menopause, regardless of age. This is called surgical or medical menopause, and Angelina Jolie went through it after having her ovaries removed to prevent cancer.

Put simply, menopause happens when the ovaries have run out of follicles. As a quick reminder: in utero, a female foetus has about seven million follicles in the ovaries; by birth, that number has reduced to two million; by puberty, there are about 400,000. During the reproductive years, 400 to 500 mature eggs are released. By menopause, none are left.

Why the ovaries lose follicles at such high rates when so few are used is still unknown. Of course, considering millions of sperm are produced by male sex organs each day but only a few dozen make it to the fallopian tubes after ejaculation, it’s not uncommon in nature to have wastage of sex cells.

Because the ovulation process has been the main source of hormone production, when there are no follicles left the ovaries reduce the production of most hormones, including oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone. Until menopause, oestrogen is the most important hormone for women, and it drops dramatically at this point, causing most of the symptoms.

But the ovaries don’t power down in an orderly fashion. They become erratic: they can produce lots of oestrogen one day and none the next. As a result, periods become more irregular than usual and unpredictable, and women may suffer tender breasts, mood swings, hot flushes, night sweats, heavy bleeding and other effects.

After menopause, ovarian tissue continues to produce some oestrogen and testosterone but in smaller amounts; by then, most of the production of oestrogen and testosterone comes from fat cells and the adrenal gland.

Impacts of menopause

Most women feel some effects from menopause—a lucky 20 per cent will have none at all, and an unlucky 20 per cent will suffer severely. Effects from menopause usually last from five to ten years. The main ones are:

• hot flushes and night sweats

• mood swings

• low mood, or depression

• vaginal dryness

• lack of libido

• weight gain

• sleep problems.

I’ve tried to include the latest information on what menopause does to the body, but some of this remains contested while menopause remains under-researched and subject to conflicting myths, diagnoses based partly in folklore, and treatments that are far from proven to be effective.

Hot flushes and night sweats: These are simply a result of the drop in oestrogen levels. Dr Rosemary Leonard, in Menopause: The answers, explains: ‘Changes in oestrogen levels can trigger a chain of events inside the brain, involving the chemicals serotonin and noradrenaline, that cause disruption to the working of the bit that controls your body temperature. It overreacts to just the weeniest change in temperature, and that, in turn, leads to flushes and sweats.’29

Mood swings and low mood: The wild fluctuation of hormones around the time of menopause is a cause of mood swings. It’s believed that oestrogen has a protective effect for good mental health, and that the drop in its levels can cause low mood and depression in some women. Leonard explains: ‘There are numerous oestrogen receptors throughout the brain and by acting on these this powerful hormone can influence not only mood, but also memory and concentration. There are a particularly high number of receptors in an area known as the hippocampus, which has an important role in regulating emotions. Oestrogen can also increase levels of brain neuro-peptides, such as serotonin, the chemical messengers that play an important role in controlling mood, appetite and sleep.’30

But this doesn’t fully explain the deep and often intermittent depression some people report experiencing in the perimenopause years, often referred to euphemistically as ‘low mood’. As medicine becomes more acquainted with the bio-psycho-social methods of healthcare—which means looking at biological, psychological and social factors that could be causing, contributing to or affecting a condition or disease—many have tried to explain away depression at this time of life as just a coincidence. The late 40s and 50s can be busy and stressful, undoubtedly, and there doesn’t seem to be adequate research to tie depression to menopause one way or the other. An Australian study found 7 per cent of women experienced depression from 45 to 54 years old, which was actually a reduction from 11 per cent in women aged eighteen to 24, and it went down to 3 per cent for women aged over 65.31 A US study of more than 2500 women found that the majority who entered menopause didn’t become depressed and those who did were more likely to have suffered depression earlier in life.32

This is one more area in which, sadly, not enough is known. Some women do report feeling better on some hormone replacement therapies—including those that involve testosterone—but this should be discussed with a trusted doctor.

Weight gain: Women and others with female reproductive systems change shape in their 50s, and it’s not a bad thing—in fact, it’s essential for good health. But as always, there’s a balance. Some are shocked by their changing shape and how hard it is to lose weight, and many want a medical explanation. However, this is just nature’s way of protecting you in older age. After menopause, the majority of oestrogen is produced by fat cells and the adrenal gland. You can lack the necessary oestrogen you need for good health; a little extra weight in older age, if maintained at a consistent level and not too concentrated around the waistline, protects you from a variety of conditions and extends life. What’s more, a little plumpness in the cheeks helps iron out the wrinkles for people concerned about that. But, of course, there’s a flip side: you can gain so much weight that additional oestrogen produced puts you at higher risk of breast and uterine cancer—not to mention a host of other chronic conditions such as diabetes and heart disease.

Sleep disturbance: The menopause years are associated with insomnia. This may be due to night sweats and hot flushes, and reduced oestrogen can also have an effect on sleep. Stress, depression and anxiety can also lead to poor sleep, and self-medicating with alcohol and caffeine will only make it worse. Lack of sleep can then lead to more stress and anxiety, and it can exacerbate aches and pains, so it’s important to seek help for sleep disturbance if it’s an issue.

Vaginal dryness, lack of libido and some other notes on sexuality: Let’s get two points out of the way up front.

First, many women and others with female reproductive systems have wonderful sex lives well into old age, and we know that most women who had a good sex life before menopause continue to enjoy one afterwards.33 Many women gain huge confidence and freedom in the later stages of life, and with that often comes fewer inhibitions and greater sexual enjoyment. On the other hand, some people will experience problems with a lack of interest in sex, or reduced arousal response due to vaginal and vulval dryness—but for those who see this as a problem, there are solutions, which brings me to my second point.

Lack of libido of course only matters if someone actually wants to have sex but finds they can’t enjoy it. However, vaginal and vulval dryness can be unpleasant for anyone, whether they’re having sex or not. The good news is, there are plenty of over-the-counter vaginal moisturisers on the market that can safely treat this issue. Ask your pharmacist about medically approved vaginal and vulval moisturisers and be sure not to confuse them with cosmetic cleansers and deodorants that can upset your vagina’s delicate pH balance.

Vaginal dryness is mainly due to reduced oestrogen, which has an effect on moisture levels and on responses to arousal. Lack of libido is still contested ground in menopause research: it isn’t recognised as an effect of menopause by the US Food and Drug Administration, and prominent endocrinologists such as the late Dr Estelle Ramey have argued menopause doesn’t decrease libido at all, and that testosterone isn’t reduced during and after menopause as it’s produced in sufficient quantities by the adrenal gland. Studies in the UK, Denmark and Australia have all suggested that there’s no correlation between menopause and lack of interest in sex.34

However, many medical practitioners report that some women suffer from reduced libido in the menopausal years and believe it’s caused by reduced oestrogen and testosterone produced in the ovaries. Testosterone may be reduced in some post-menopausal women, and hormone therapies can affect its levels. Some studies have shown that testosterone treatment may improve sex drive in women, and an increasing number of medical practitioners believe that the hormone may help with mood and even pain reduction. However, testosterone treatment in women remains controversial.

Libido is obviously affected by enjoyment. After menopause, the vagina shrinks and loses some elasticity (this is called atrophy), and along with vaginal dryness, this could cause pain during sex, which in turn could reduce libido. Jane Ussher points to studies of lesbians that show increased sexual enjoyment compared to heterosexual women at this stage of life because they were able to discuss their body changes more openly and negotiate different ways of pleasuring each other, ‘largely because they shared a broader definition of “sex” which wasn’t tied to penetration’.35

Non-hormonal vaginal moisturisers, vaginal oestrogen therapy and/or using plenty of lubrication can improve enjoyment of sex. A pelvic physiotherapist can help if you experience pain during sex, and they can work wonders if you have incontinence issues or other generalised pelvic pain. Regular use also helps keep the vagina elastic.

It’s important to remember that men are also experiencing reduced testosterone levels at this stage of their life and can start to experience sexual problems too, including reduced libido, and issues getting and maintaining an erection. And, just as women put on weight around this time, so do men. A reduced libido could also be influenced by a lack of attraction—so much has been said about women losing their looks and attractiveness after the age of 50, but attraction works two ways. And by the way, among heterosexual couples, seven out of ten divorces are instigated by women.36 Just sayin’.

Sex drive is influenced by many factors, not just hormones, so any discussion of sexuality must look at the big picture of someone’s life.

Hormone replacement therapy

Hormone therapy for menopause is nothing new. Decades before Robert Wilson published Feminine Forever in 1966, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved oestrogen therapy for treating the effects of menopause. And Chinese medicine has been prescribing hormone treatments for centuries: apparently wealthy women used to eat the dried urine of younger women to ease their symptoms.37 What Wilson did, however, was classify menopause as a deficiency disease for which there was a cure, HRT, that suddenly seemed not only helpful but necessary—never mind that decreasing hormone production is a natural part of growing older for everyone.

In 1970 the late feminist and endocrinologist Dr Estelle Ramey became famous for rebutting a congressman’s claim that women were unfit for important jobs because of ‘raging hormonal influences’. A woman couldn’t possibly be president of the USA, the congressman—a former surgeon—said: ‘Suppose we had a president in the White House, a menopausal woman president who had to make the decision of the Bay of Pigs?’ Ramey immediately wrote to the Washington Star, reminding readers that their president had, in fact, had a hormonal imbalance as he made decisions during the Cuban missile crisis: John F. Kennedy suffered from Addison’s disease, in which the adrenal glands don’t produce enough hormones.38 So much is written about the effect of oestrogen on a woman’s mood and her ability to think clearly; so little on the effect of testosterone on a man’s mood, even though we know it can influence his ability to think clearly. Perhaps this is partly why crying is widely considered irrational and feminine, but anger is apparently rational and masculine.

The Islamic Republic of Iran has declared that women can’t be judges because they’re too emotional and irrational. One wonders what the Iranian ayatollahs were thinking as they watched the emotional testimony of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh during his selection hearings before the US Congress in September 2018.

Wilson’s book quadrupled the sales of hormone replacement therapy. For decades, women were told that long-term use wasn’t only safe but also protected them from a variety of diseases, including osteoporosis, heart disease and some cancers. Throughout the 1960s and 70s studies found high doses of oestrogen were causing increased risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke and endometrial cancer, so pharmaceutical companies developed lower doses and added a synthetic progesterone, progestin, to protect against endometrial cancer. They also developed better forms of hormone delivery, such as patches. By the 1980s, researchers—many sponsored by pharmaceutical companies—were claiming that oestrogen replacement in postmenopausal women could protect against Alzheimer’s disease, age-related eye disease, colon cancer, tooth loss, diabetes and Parkinson’s disease.39 It was being prescribed, long-term, for any and all women, regardless of their symptoms, in order to protect them against chronic disease.

Two influential studies blew all this out of the water. A 2002 study by the US Women’s Health Institute40 and the 2003 British Million Women Study41 found that combined oestrogen and progestin hormone therapy increased the risk of breast cancer, and the WHI study also showed it increased the risk of heart attacks and stroke. Later results from the WHI study on oestrogen-only therapy produced similar signs that risks outweighed benefits. But the breast cancer risk found in the 2002 WHI study was exaggerated by media reports, which failed to understand the meaning of relative risk and caused a great scare among women worldwide using HRT. Critics later pointed to issues with the control group in the WHI study, which had an average age of 63—much older than the typical age women are prescribed HRT.

Even taking into consideration the criticisms, together the studies showed the purported benefits of both oestrogen-only and combined hormone replacement therapy were overrated and that risks outweighed benefits in many cases. The studies helped improve scientific understanding of HRT, and medical advice changed as a result: long-term use is no longer recommended, and the benefits are considered to outweigh the risks only in women with impacts that negatively affect quality of life when started close to the date of menopause or in perimenopause, and before the age of 60. In 2013, an international group of women’s health organisations worked together to review all the data on HRT; their Global Consensus Statement on Menopausal Hormone Therapy claims the benefits of taking HRT outweigh any negatives for women under 60.42

However, vast numbers of women continue to be both over-treated for the effects of menopause—usually wealthy women—and under-treated—usually poor and minority women.

The US FDA warns that menopausal hormone therapy isn’t for everyone, and that in some women it may cause serious side effects including blood clots, heart attacks, strokes, breast cancer and gall bladder disease. While the FDA acknowledges that the therapy may help relieve hot flashes/flushes, night sweats, vaginal dryness and pain during sex, and may help protect bones, its official advice is that: ‘Menopause Hormone Therapy should always be used at the lowest dose that helps and for the shortest time that you need it.’43

This isn’t to say the controversy over HRT is settled. Some critics are still nitpicking at the Women’s Health Institute and Million Women studies, and opponents of HRT claim the risks shown in these comprehensive studies are being ignored by those with an investment in selling hormone treatments.

The HRT scare that resulted from reporting on the WHI study provided a boon to a new part of the menopause industry: bioidentical hormone therapy. Proponents of this therapy claim it’s natural because the hormones are derived from plants and said to be identical on a molecular level to the chemicals produced in the body. But these hormones are manufactured synthetically, like most others used in therapy, so claiming they’re natural is misleading. Body-identical hormones used in HRT also have the same chemical structure as those produced in the body. As the Australian Menopause Society states: ‘It is important to realise that no hormone used in any preparation of pharmaceutical grade menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) or compounded “bioidentical therapy” is “natural”. They are all synthesised in the laboratory from some precursor by enzymatic manipulation.’44

A selling point of bioidentical hormone therapy is that treatments are individualised by testing each patient’s hormone levels to develop a tailored prescription. But since hormone levels fluctuate constantly, the use of a single test is limited. The bioidentical hormone treatments compounded, or made up, by pharmacists can’t be tested for safety or efficacy by regulatory agencies; this means the therapy isn’t recommended as a treatment by the International Menopause Society, the North American Menopause Society, the Australasian Menopause Society or the British Menopause Society. According to the 2016 Revised Global Consensus Statement on Menopausal Hormone Therapy: ‘The use of custom-compounded hormone therapy is not recommended because of lack of regulation, rigorous safety and efficacy testing, batch standardisation, and purity measures.’45

Anyone who decides to proceed with bioidentical hormone therapy should only do so under the care of a trusted provider who has some qualifications in treating the effects of menopause. And the patient must accept that, as with all hormone therapies, there are risks associated with the use of bioidentical hormones.

Attitudes to menopause

Much is made of the fact that human beings are one of only five mammals to go through menopause: the other four are all whale species. New research seems to support the ‘grandmother theory’ of evolution in whales, observing that grandmother whales play an active role in the survival of their young.46

Pregnancy is a much more onerous process for humans than for most other mammals, and so is raising a child. Few mammals are as exposed to health risks during pregnancy and childbirth as humans, and few mammalian offspring are as helpless for as long as human children.47 In The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir wrote that women were ‘the most deeply alienated of all the female mammals; and she is the one that refuses this alienation the most violently; in no other is the subordination of the organism to the reproductive function more imperious nor accepted with greater difficulty’.48

Shouldn’t we then see the end of our reproductive capacity as a great evolutionary blessing, rather than a curse?

Grace Johnston, who wrote Menopause Essentials, talks about her experience of menopause as a veil being lifted, allowing her to see everything in her life more clearly and giving her back energy and life focus. She adds that the post-menopause years are ‘the best, happiest, and most productive time of my life’.49

In contrast, Rose George—a journalist who’s written extensively on menopause—said of her depression during perimenopause: ‘It’s astonishing that I managed to shower, because I know already that this is a bad day, one when I feel assaulted by my hormones, which I picture as small pilots in those huge Star Wars armoured beasts that turn me this way and that, implacable.’50 She listed other symptoms as: ‘peeling skin, sore tendons, poor sleep, awful sadness, inexplicable weeping and various other “symptoms” of menopause that you can find listed if you look beyond the hot flushes and insomnia’.

A 2009 Australian study found that women assessed to have high emotional intelligence who approached menopause positively appeared to suffer less severe menopause symptoms as well as less psychological distress than women assessed to have lower emotional intelligence. The researchers concluded that ‘women who expect menopause to be a negative experience or are highly stressed or distressed may be more likely to experience a more negative menopause’.51

After reviewing the literature and conducting in-depth interviews with sixteen Australian women, Jane Ussher concluded in Managing the Monstrous Feminine: ‘Whilst the menopause and midlife are marked by change, at an embodied level, as well as in women’s relationships, roles, and in opportunities available, and whilst ageing does bring sadness and loss, if women can tolerate the ambivalent feelings about these changes, their experiences can be positive.’52

If we accept that menopause is a disease, then we accept that something is wrong with it, that it isn’t normal, and we surrender our bodies once again to a medical industry that’s still controlled by men. Up until now, this industry has sold unproven and ineffective—and at times dangerous—treatments for menopause symptoms, and in 2019 it remains largely ignorant of the full picture of menopause and ageing in women. However, glossing over symptoms can feed into a vacuum of knowledge about sufferers’ health, encouraging them to be silent and self-blaming. As Marina Benjamin argues, ‘the kind of cheerleading that insists we can become strong by embracing menopause does women few favours, since it makes those of us who suffer and struggle with it feel cowed by failure and self-recrimination. We have a right to complain, damn it.’53

Somewhere we all have to find a happy medium where we can limit suffering without treating ageing as something that’s only a disease in women. In The Fountain of Age, Betty Friedan wrote: ‘The finding emerges that the difference between knowing and planning, and not knowing what to expect (or denial of change because of false expectations) can be the crucial factor between moving on to new growth in the last third of life, or succumbing to stagnation, pathology and despair.’54

As a society, we have to talk more openly and honestly about menopause at home, work (in menopause cafes, perhaps), in popular and high culture, online and in the news media. We have to know what to expect, understand that everyone who experiences menopause will have a different ride through those years, and believe that life after menopause can be exciting and fulfilling—maybe even better. We have to listen to those who welcome this stage of life as closely as we listen to those who dread it and those who suffer unpleasant effects.

We have to unpick the so-called symptoms of menopause from the normal processes of ageing, of which menopause is a part. Everyone experiences reduced hormone production as they age; everyone experiences hot flushes and night sweats, gets wrinkles, has more aches and pains and changes to hair and skin. But because menopause is tied to the uterus—the source of so much corruption!—and the female reproductive capacity, it is pathologised, turned into a condition that has to be managed by medicine.

We must also demand more research into menopause and menstruation, along with increased funding from government bodies for research into medical and non-medical treatments for ill effects these natural cycles can cause in some people’s lives, and we must make sure working class and minority women and others with female reproductive systems aren’t excluded or priced out of effective treatments.

Whether it’s improving information about, or treatments for, the effects of menstruation or menopause, the lesson comes down to that old chestnut: we have to change society so that everyone’s contributions and unique experiences are understood, accepted and valued.