1.Introduction

This chapter takes as its principal impetus a widespread and

somewhat controversial belief in certain parts of world that speakers from

North America “don’t do” irony. Whether this belief is simply an “urban

myth” or a specious linguistic stereotype is one of the questions that

inform the later sections of this chapter. There is however compelling

evidence that the issue has some contemporary everyday relevance insofar as

it manifests frequently in discussions and debates in the public sphere.

Even a rudimentary search of the internet, keying in the quotation in the

title of this chapter, will yield thousands of relevant results. This

internet evidence intimates a number of things. First, it suggests that

interest in this topic is extensively and almost exclusively non-academic in

origin. Second, the sources supporting the evidence are skewed

proportionally towards Britain and Ireland, suggesting that this is where

the debate is principally situated. For instance, the top ten placed

results, in an internet search conducted in English by this author on

November 9th 2015, all derive from sources from the eastern side of the

Atlantic, results which are materialised in “chat”, posts and discussion

pieces dating from 2004 up to January of 2015. Moreover, this irony “debate”

is recorded not just in informal pieces but in more eminent outlets such as

the UK’s Guardian and Independent

newspapers, and alongside these “quality” print media articles was, in fifth

position in the search, a posting on the topic from the BBC’s online news

magazine. These sources suggest that the issue prompts a level of conscious

discussion in Britain and Ireland which is not mirrored in Canada and the

USA. Whatever its terms and wherever its source, though, this is a debate

about perceptions of language practices in general, and, more specifically,

about how different cultural and geographical contexts intersect with

certain kinds of linguistic-pragmatic inferencing strategies. Indeed, there

is good precedent for initiating a linguistic analysis on the basis of “lay”

perceptions or everyday beliefs about language practices (Bauer and Trudgill 1998). Therefore, and without

attempting play to, or fuel, a populist agenda, this article seeks to build

a systematic, empirically-grounded investigation of the cross-cultural

production and reception of irony.

It is of course a commonplace in much linguistic-pragmatic

research to position irony at the centre of many forms of social

interaction, including humour, sarcasm, banter, teasing, politeness, satire

and parody. For instance, Nash offers an overview of the stylistic

intersections between humour, sarcasm and irony, noting the special

“counter-coding” strategies used in the generation the last of these forms

of discourse (Nash 1985: 152).

Cognisant of this broader research backdrop, this chapter narrows the focus

by exploring the way in which ironic situations are processed and

interpreted in different cultural contexts. It is also argued that more

emphasis should be given in pragmatic accounts of irony to the role of

individual language users in both the generation and the classification of

ironic utterances and situations. In pursuit of these related aims, an

online experiment is generated which comprises different narrative

scenarios, to which reactions are gathered from over 300 anonymous

informants world-wide. The scenarios used in the experiment are relayed

through six short 44-word stories, some of which lay good claim to being

considered “ironic”, and others less so. The data gathered from the

informants’ responses offers fascinating insights into structured linguistic

and cultural practices. It also helps challenge and re-cast the central

assumption behind the analysis; that is, the perception of many in the UK

and Ireland that people from North America “don’t do” irony. The study

therefore places ordinary users of language centre stage, allowing them, not

academic researchers, to decide on the ironic status of different kinds of

discourse. The results from the on-line questionnaire, presented later,

reveal not only broad patterns of response across a genuinely international

group of language users, but the data itself throws up many surprises and at

times raises many more questions than it can realistically answer.

The bulk of this chapter is devoted to elucidating a method

for linguistic-pragmatic analysis, to gathering empirical data, and to

offering an extensive discussion and interpretation of the results obtained.

This is therefore not the place to offer an exhaustive account of the

substantial and expanding body of research in linguistic pragmatics on the

discourse of irony; nor is it feasible to present a detailed critical

overview of such work. Suffice it to say, many scholars have advanced their

own models for ironic communication drawing on a host of theoretical

perspectives. As noted, Nash accounts for irony in terms of “counter-coding”

where an utterance is juxtaposed against acknowledged facts, accepted

attitudes and what he terms “broad truth conditions” (1985: 153). In their well-known study of the

trope, Sperber and Wilson postulate an echoic model of

irony which is built on the logical distinction between “use” and “mention”

(1981; and see Wilson and Sperber 1992). From the

extensive range of other current frameworks of analysis, Attardo conceives

irony as “relevant inappropriateness” (2000), while Partington uses a corpus-based approach to talk of

irony in terms of “reversal of evaluation” (2007). By contrast, Clark and Gerrig (1984) view irony as a form of

“pretence”, Utsumi (2000) as

“implicit display”, and Giora

(1995) as “indirect negation”. Additional frameworks include

Barbe’s discussion (1993) of the

implicit and explicit aspects of irony, noting how the former type has to be

discovered by “an initiated audience”, while Kapogianni (2011) explores the connection between

ironic effects and “surreal” elements in message composition, where speakers

generate irony by producing strikingly unrealistic or unexpected utterances.

Separately, Kapogianni (2016)

illustrates the ways in which irony functions at the semantics/pragmatics

interface by postulating three components of the ironic operation: the

vehicle, the input, and the output.

Where each of the studies check-listed above present

individually nuanced models of analysis, there are as many other linguistic

studies that investigate irony more broadly across different genres of

discourse. While Gibbs and Colston

(2007) import insights from cognitive linguistics throughout

their collection of essays, Dynel

(2014) offers a neo-Gricean perspective on occurrences of irony

in contemporary television shows. Benwell

(2004) examines the use of irony as a defence against sexism in

men’s lifestyle magazines whereas Shen

(2009) offers a stylistic investigation of “context-determined

irony” in prose fiction. Other publications have explored irony in forensic

contexts, such as Simpson et al.’s discussion of legal judgements and

rulings which reference, or are prompted by, assessments of irony (2019: 27–30; see also Kelsey and

Bennett 2014). While this overview is no more than a gloss of the rich

variety of linguistic research on irony, there is one particular study that

has helped inform directly the design of the present analysis. This is

Shelley’s conceptualisation of irony as “bicoherence” (2001) which builds an elegant model of

situational irony out of a corpus of media reports about episodes and events

that participants have described as “ironic”. Although research on nonverbal

irony is often separated off from the dominant focus on verbal irony,

Shelley makes a good case for seeing the same organising principles at work

in both ironic situations and ironic utterances. Recourse will be made to

this and other relevant aspects of Shelley’s study in the section that

follows.

The present analysis does not seek to dismiss or reject per se

any of the existing approaches to irony touched on above, although by the

same token, it does not align itself exclusively with any one of the

prevailing schools of thought in linguistic pragmatics. Instead, this study

attempts eclectically to collate different models of analysis, importing

those aspects of a particular model that offer useful theoretical or

explanatory currency. In this context, Simpson (2011) has proposed an umbrella definition for irony,

and although the theoretical justification for these constructs is offered

elsewhere (2011: 39–42), the

definition yields a reasonably serviceable framework that will inform the

experimental design over the remainder of this chapter. The umbrella

definition of irony, along with two associated sub-definitions, runs

thus:

Irony – umbrella definition:

The perception of a conceptual paradox, planned or

un-planned, between two dimensions of the same discursive event.

- A perceived conceptual space between what is asserted and what is meant.

- A perceived mismatch between aspects of encyclopaedic knowledge and situational context (with respect to a particular discursive event).

The idea of a paradox is preferred in the

definitions, rather than the more familiar expressions like “oppositeness”

or “incongruity”, in some measure to help accommodate many of the approaches

to irony touched on earlier. The significance of the

perception of irony is central to the definitions:

irony cannot work without some perception of it, and while much irony

undoubtedly passes us by in everyday interaction, we also perceive irony

that was not planned or intended (see for example Gibbs et al. 1995). Where appropriate, other

aspects of the umbrella definition will be fleshed out over the remainder of

the chapter, but the focus will now shift to the design and methods of the

online experiment itself.

2.Methodology: “Six Little Stories in Need of a Response”

The experiment was designed to elicit reactions to various

scenarios portrayed in six very short narratives. The sources and

foundations for the six stories will be amplified shortly, but the general

structure of the experiment was to capture anonymous informant responses

through an online questionnaire. The only personal details sought in the

questionnaire concerned informants’ age, gender, and, of course,

nationality. Questions soliciting information about educational attainment

were deemed inappropriate on the grounds that informants might feel that the

experiment was designed to test either linguistic proficiency in English or

general intellectual and cognitive skills, or both. Finally, the

questionnaire offered an option for participants, if they wished, to record

their email addresses in order to receive the results of the experiment. On

the understanding that a copy of the final paper in portable data format

would be passed on electronically, 223 of the respondents documented their

contact details in this manner. Interestingly, less than one third of the

emails recorded an academic institutional affiliation – testimony, perhaps,

that the experiment had had the desired reach beyond the academe.

Informants were required to react to the six scenarios

presented sequentially in the questionnaire in such a way that progress to

subsequent stories was only made possible through the completion of the

previous stage. For each story, informants had two tasks. The first, an

obligatory phase, required them to offer in the box provided a

single word that best described their feeling about, or

reaction to, the story they had just read. The second, optional phase

allowed informants to record, if they wished, any other reactions or

feelings they had about the story, and a larger box was provided to capture

this more discursive type of commentary. The questionnaire was created by

and hosted on the online survey tool Questback. A link and invitation to

complete the questionnaire was circulated using social media platforms such

as Twitter and Facebook, and the experiment was disseminated through the

library at Queen’s University Belfast. A Word version of the first page of

the survey is reproduced as Appendix 1.

As argued earlier, the core of the experiment hinges on

stories whose outcomes have not been deemed “ironic” by the academic

researcher, but rather, have had the status of irony conferred upon them by

participants in the discursive event itself. In contrast to the analysis of

invented or contrived data, the (potential) presence of irony in the

relevant stories used in this study is attested by commentary in the public

domain through which these narratives were played out. In this respect,

three of the six stories are “ironic” in the sense that they have been

reported as such by participants in the original context of interaction. Of

the remaining stories, two “non-ironic” stories are taken from research

literature in experimental psychology (more on which below) while the sixth

story has a rather more contentious status insofar as differing commentaries

exist about whether or not it could claim to have some ironic status (again,

more on which below). Of course, at no point in the online instruction brief

was the term “irony” used; informants could offer any single word in the

obligatory phase and importantly, it was made clear to them that the same

word could be used to describe different stories.

As noted in Section 1

above, experimental consistency inhered in the rendering down of each source

story into a short text of forty-four words. In addition to this

triangulation for length, all of the stories were levelled stylistically by

being stripped of any potentially “irony inducing” expressions that might

signal some kind of conceptual paradox between the conjuncts in the story.

Expressions that were avoided included Mood, Comment and Conjunctive

Adjuncts, as in, respectively, “obviously”, “unfortunately” or “however”,

and related expressions of Extension and Enhancement, as in “but” or

“although” (see Halliday

1994: 81–84, 219–220; Halliday and

Matthiesson, 2004: 126–132, 395–413). The first story in the

experiment was drawn from a genuine news report that ran in the British

print media in December 2011. The story concerns a car driver who,

immediately after his anger management class, became involved in a road rage

incident. Under the header “The Filth and the Fury”, the Daily

Mail describes how Philip Croft launched a “four-letter tirade

at a policeman … on his way home from an anger management course”

(Daily Mail 2011). Given that the anger management

course had been made compulsory after an earlier offence, the District

Judge’s summation leaves no doubt about his pragmatic interpretation of the

episode: “There’s a certain irony that on your [i.e. Croft’s] way back from

an anger management session you behaved like this with a police officer.”

Rendered down into the stylistic template set out above, this is how the

story appears on the questionnaire:

Story 1:Mr. Jones had been ordered by a court to take part in anger management classes. On his way home from one of his classes, he was pulled over for speeding. Mr. Jones verbally abused the police officer and was later convicted for the offence.

For ease of reference when assessing the quantified results

later in this chapter, this story will be referred to hereafter as “Story 1:

Anger Management”, although the added descriptor was

not of course present in the online survey. Similar mnemonic descriptors

will be added to the remaining five stories.

The second of the “ironic” stories is derived from data

presented in Shelley’s corpus-based study of irony in electronic news

sources (Shelley 2001). As

outlined in Section 1, Shelley’s

data is developed from press reportage in which the lemma IRONY and its

derivatives appear. One particular episode in his corpus lends itself well

to the present study in that it features both an appropriate narrative event

and a suitable commentary on the event from one its

participants. This is the story of the fire-fighters of Station 20, Clark

County, Las Vegas, who on one hapless afternoon were called out to put out a

fire. Only later were they to discover that the lunch that they had been

cooking, of what seemed in the report to be chicken goujons, had been left

on the stove and had set ablaze the fire station. A spokesperson for the

service captures the episode thus: “It just shows that if it can happen to

us, it can happen to anyone … The irony’s not lost on it.” (adapted

from Shelley 2001: 775–6).

Modified following the stylistic template, and appearing in third position

in the questionnaire, this how the “fire brigade” story reads:

Story 3:Members of the fire brigade were preparing a lunch of chicken goujons. They were called suddenly to attend to a fire in a nearby residence. When they returned, they discovered the chicken goujons had caught fire, and had set the whole fire station ablaze.

The genus for the third of the three “ironic” stories is from

media coverage of an episode involving a power outage at a soccer ground.

The online UK news platform Metro describes how, in

December 2013, fans of English football club Leicester City used their

mobile phones in an attempt to light up their stadium after the floodlights

had failed. Given that the stadium was sponsored by the King Power conglomerate (though strictly, in spite of public perception, not itself an energy provider), the irony of the situation was teasingly captured in comments like

the following: “The floodlights went out midway through the clash at the

aptly named ‘King Power Stadium’ – with power cuts

affecting the whole area” (Metro 2013; my emphasis). This scenario,

the “power cut”, formed the basis for the sixth story on the

questionnaire:

Story 6:A soccer team, sponsored by a national electricity company, was playing its local rivals in an important match. The floodlights went out midway through the contest with power cuts affecting the whole area. The referee stopped the match until the problem was finally solved.

Turning to the development of the “non-ironic” stories, some

useful source material was taken from a particular body of empirical

research on reading and text processing (Egidi and Gerrig 2006; Rapp

and Gerrig 2006). This research explores principally the

psychology of readers’ preferences for narrative outcomes and examines the

way readers react to certain characters’ goals and actions in stories.

Bluntly put, none of the material used in such experimentation is remotely

connected to irony; it is instead focused on how readers tend to identify

with stories with that are consistent with a priori

expectations and how reading time is affected when stories present unusual

or “dispreffered” outcomes. One scenario developed by Egidi and Gerrig (2006: 1322; following earlier

work by Huitema et al. 1993 and

Poyner and Morris 2003)

involves the sun-loving character Dick who likes to swim and sunbathe.

Planning his vacation, Dick visits his travel agent and “ask[s] for a plane

ticket to Florida”. Egidi and Gerrig observe that readers are consistently

less quick to read an inconsistent action in the same

context, as in their alternative scenario when Dick asks his travel agent

for a plane ticket to Alaska. Another interesting story, developed in the

same paper (2006: 1325–6), is when

a man robs a well-known coffee franchise and makes speedily for the Mexican

border. In one variant of the story, however, the robber interrupts his

getaway by stopping at the side of the road for a sleep. To re-iterate,

these scenarios are not connected to the study of irony but are instead

concerned with how readers deal with inconsistent situations where

characters’ actions contradict their purported goal. In this respect, they

make for excellent contrastive material and in the questionnaire they have

been adapted into stories 4 and 5:

Story 4:Mr. Smyth had just robbed a city bank and was making good his escape in his getaway car. He drove at speed towards the border. After fifteen minutes on the road, he pulled over and had a snooze at the side of the road.

Story 5:Ms. Smyth worked in an office in the city. She enjoyed her holidays in the sun and was always looking forward to her summer break in warmer climes. As soon as her last day at work was over, she booked a flight to Iceland.

The final story in the experiment has an unusual provenance

insofar as it draws on a debate about irony that was played out in the

sphere of popular entertainment. The detail of this debate is reported

elsewhere (Simpson 2011: 42–44)

but the substance of it concerns the lyrics of the song “Ironic” by Canadian

singer-songwriter Alanis Morrissette and the subsequent unpacking of these

lyrics by Irish stand-up comedian Ed Byrne. In essence, Byrne interrogates

the semantic and pragmatic foundations of the song, concluding amongst other

things that the only thing that is ironic about “Ironic” is that it was

written by someone “who doesn’t know what irony is”. Byrne’s overall

position is that the singer “keeps naming all these things in the song that

were supposed to be ironic, and none of them are. They are all just …

unfortunate”. Although not the only comedian to probe these lyrics (see

Shelley 2001: 784), Byrne

takes particular issue with the sequence: “And isn’t it ironic, dontcha

think? … It’s like rain on your wedding day” (Simpson 2011: 43).

On the potential of this “wedding day” scenario to embody

irony, Byrne quips with the following proviso: “Only if you’re getting

married to a weather man and he set the date”. Clearly, the debate enacted

here not only offers potential for empirical investigation but the state of

affairs it depicts can easily be integrated into the test materials. It is

the ‘wedding day” scenario therefore that informs the remaining story in the

questionnaire:

Story 2:Ms Smyth had been looking forward to getting married for some time. She and her friend had chosen a fine white dress for the ceremony, which was held on the 3rd of June at a local country club. It rained on her wedding day.

To round off this section, some observations will be offered

on the process of textual composition of the six stories and on some of the

issues and challenges the process raises. Thereafter, and working up from

the data, a model for situational irony (and its comprehension) will be

suggested. This model offers a more fine-tuned account within the broader

terms of the umbrella definition set out in Section 1 above.

As noted, it was important in the composition of the stories

to avoid any kind of evaluative modality that might direct readers to a

specific interpretation. Particularly important was the circumvention of

aspects of text that might signal the presence of the kind of conceptual

paradox that is inherent in irony. Of course, the textual structure that

this circumvention engendered tended to make the six stories seem rather

bland, perhaps disengaged or even somewhat “Hemingway-esque” in feel.

Although necessary, this pattern of levelling did elicit some reactions in

the more open responses on the questionnaire, more on which later. A related

issue arose in other aspects of composition that ran the risk of attracting

prescriptive meta-commentary. For instance, the opening to Story 3 as

originally drafted was “The fire brigade were making their lunch” but

informal feedback from university colleagues at the pre-experimental stage

tended to draw attention to the “lack of agreement” between the singular

subject and plural verb form (cf. “The fire brigade was making

its lunch”). If only to avoid prescriptive reactions to

grammar that are not relevant to the aims of the study, the text of 3 was

altered accordingly (and a similar strategy invoked for Story 6, “A soccer

team was playing … its local

rivals”). Additionally, in the transition from source narrative to test

narrative, some stories were fine-tuned to avoid possibly context- or

culture-dependant associations. For instance, “soccer” was preferred to

“football” because of the wider sphere of reference the former term enjoys

outside the UK and Ireland. A reverse of this transposition is in Story 5:

Vacation, where the USA-orientated destination of

“Alaska” was replaced by “Iceland”, simply on the grounds that the latter

encapsulates a perhaps more universal embodiment of a location with a cold

climate. Similarly, the explicit allusion to the Mexican

border was removed in Story 4: Robbery, again because of

geographical specificity. With these late revisions in place, the survey

opened on the 8th of June 2015 and closed on 31st December 2015. The results

presented in Section 3 below are

based on the 321 responses collected during this period.

One corollary of the bottom-up development of ironic

situations for experimental purposes is that it allows theoretical

constructs to be developed and refined post hoc from the body of data

itself. The observations that follow are sustained by three of the stories:

Story 1: Anger Management, Story 3: Fire

Brigade and Story 6: Power Cut. The situations

portrayed in this group of narratives enable a more nuanced

linguistic-pragmatic account of the umbrella definition to be attained.

These refinements concern especially the second sub-definition of irony;

that is, where irony inheres in a mismatch between aspects of encyclopaedic

knowledge and situational context with respect to a particular discursive

event. This broad characterisation implies the presence of two distinct sets

of knowledge for the understanding of an ironic situation. The first of

these is a more stable conceptual repository that mirrors and parallels

various comparable conceptual units that have been developed in both

discourse analysis and cognitive linguistics. Far from forming an exhaustive

list, analogous terms which suggest themselves are “mental space” (e.g.

Fauconnier and Turner

2002: 40), “frame” (e.g. Goffman

1986: passim), “conceptual frame” (e.g. Minsky 1975: 211), “memory organisation packet”

(e.g. Schank 1982: 95) and

“encyclopaedic entry” (e.g. Sperber and

Wilson 1986: 86–93). Figure 1 illustrates how this more constant conceptual space,

situated in the box on the left, is characterised by a number of attributes:

it is encyclopaedic, universalistic,

stative, atemporal and

enabling.

Figure 1.Modelling situational irony

The first two boxed attributes on the left encapsulate the

conceptual space along the broad lines of the cognate terms in linguistics

just mentioned; that is, as beliefs, memories and assumptions about things

and states of affairs. In contrast, both of these more abstract attributes

collide with the palpable features of the ironic situation, positioned in

the circle on the right of the figure, where generality gives way to the

particular and the local aspects of

the discursive event. The staggered arrow in the centre of the Figure

signals the paradox and captures the mismatch between the two sets of spaces

through semantic relationships of negation, contradiction, and relational or

complementary antonymy (see Jeffries 2010). The next two terms in the left

hand box, stative and atemporal, highlight

more narrowly the framing aspects of this dimension of situational irony.

These aspects can be teased out and brought to the fore through the

grammatical forms used to describe them. For instance, the relevant aspects

of Story 3: Fire Brigade might be cast propositionally as

“Firefighters put out fires”. The expression of this propositional form,

through the so-called “timeless present”, is therefore as a

universal truth. This generic structure, which has no

specific action or time reference, cannot be inflected for aspect or for

other tenses. The same level of generality applies to the core propositions

in the other two stories: Energy companies provide power

and Anger management classes prevent people from doing angry

things. In contrast, the parallel aspects of situational

context portrayed on the right of the Figure are anything but generic. On

the one hand, they capture temporal episodic information

through tenses other than the timeless present; on the other, they employ

grammatical resources that are punctual in the specific

sense of describing action that is grounded in a particular time. Additional

particularised reference is achieved through deictic words, demonstrative

determiners and definite and indefinite reference – all of which serve to

pick out “real” individual actors, participants and places. The fifth

category on the Figure is cued by Shelley’s observation that ironic

situations often have a negative association, or are prompted by a goal that

is unachieved (2001: 784–5).

Shelley describes this aspect of situational irony in terms of “manner”,

which is the main measure of the distance between an ironic situation and

“the goals, concerns, and preferences that a cognizer applies to it” (2001: 785; and see also Partington’s

discussion of irony [2007: passim]

in terms of “reversal” of expectation). Certainly, the three stories here

are all grounded in discourse contexts that are potentially facilitative,

positive or biased towards a good outcome for their participants; in

contexts that are in other words enabling. By contrast, the

actual outcomes in all three stories are dis-enabling in

the sense that the positive expectations are thwarted. In the Figure, each

of the core propositions below the box on the left are opposed through

complementary opposition or antonymy by negation in the corresponding

grammatical realisations on the right. Indeed, this sense of being “let

down” by the contextual outcome may be part of the humour-inducing aspect of

some kinds of irony, but it may also account for qualitative assessments of

certain forms of irony. Although an area of investigation that is beyond the

scope of this chapter, corpus analysis reveals for instance how the lemma

IRONY attracts particularly common collocates, notably in judgements of

irony as “heavy”, “bitter” or “grim” (Simpson 2011: 41–42). For the moment, attention will focus on

the results of the Questback survey and to this effect the next section will

offer an overview and assessment of the data generated by the

questionnaire.

3.Results and discussion

Over its course, this section will assess the broader patterns

of response collected through the survey, before drilling down into some of

the more nuanced qualitative features of subjects’ individual contributions.

The section concludes, by way of denouement, with the final set of

quantified results, aided by tabulated histograms that summarise the

outcomes of the survey. The data set reveals much about consistency of

linguistic-pragmatic processing across often diverse cultures, with an, at

times, remarkable level of convergence in patterns of response to some of

the stories. This convergence is striking when we recall that informants

were permitted only a single word response in the first stage of the online

protocol. Nevertheless, the results also throw up many surprises and

inconsistencies, and in some areas, more questions are raised than can be

answered in a study of this scale. Attention will be given later to where

the results point towards further research questions, or to possible

modifications to the existing methodology and experimental design.

In terms of very raw numbers, the 321 responses which form the

data set break down as follows: North America (NA) produced 169 completions

(52.6% of the total), while the UK & Ireland (UKIre) realised 63

completions (19.6% of the total). Within the latter category, four

informants declared their nationality as “Northern Irish” and two as

“Scottish”, although the broad-based assimilation of these national

affiliations into the umbrella grouping “UK and Ireland” is, it is hoped,

uncontentious. There remain 89 informants from what can be classified,

admittedly less than ideally, as the “Rest of the World” (RoW) group. This

group made for 27.8% of the survey, and of these 89 informants, the largest

national affiliations in size of grouping were Chinese, Spanish, Brazilian

and French, moving respectively, from 20 down to 12 informants in each

group. At the other end of the scale, there were 11 single-nationality

responses, from individual informants as far apart as Cyprus, South Korea

and Sierra Leone. Although the aims of the present study preclude detailed

exploration of this very heterogeneous group, it is still worth factoring in

RoW responses where they intersect in interesting ways with the comparative

analysis of the other two groups.

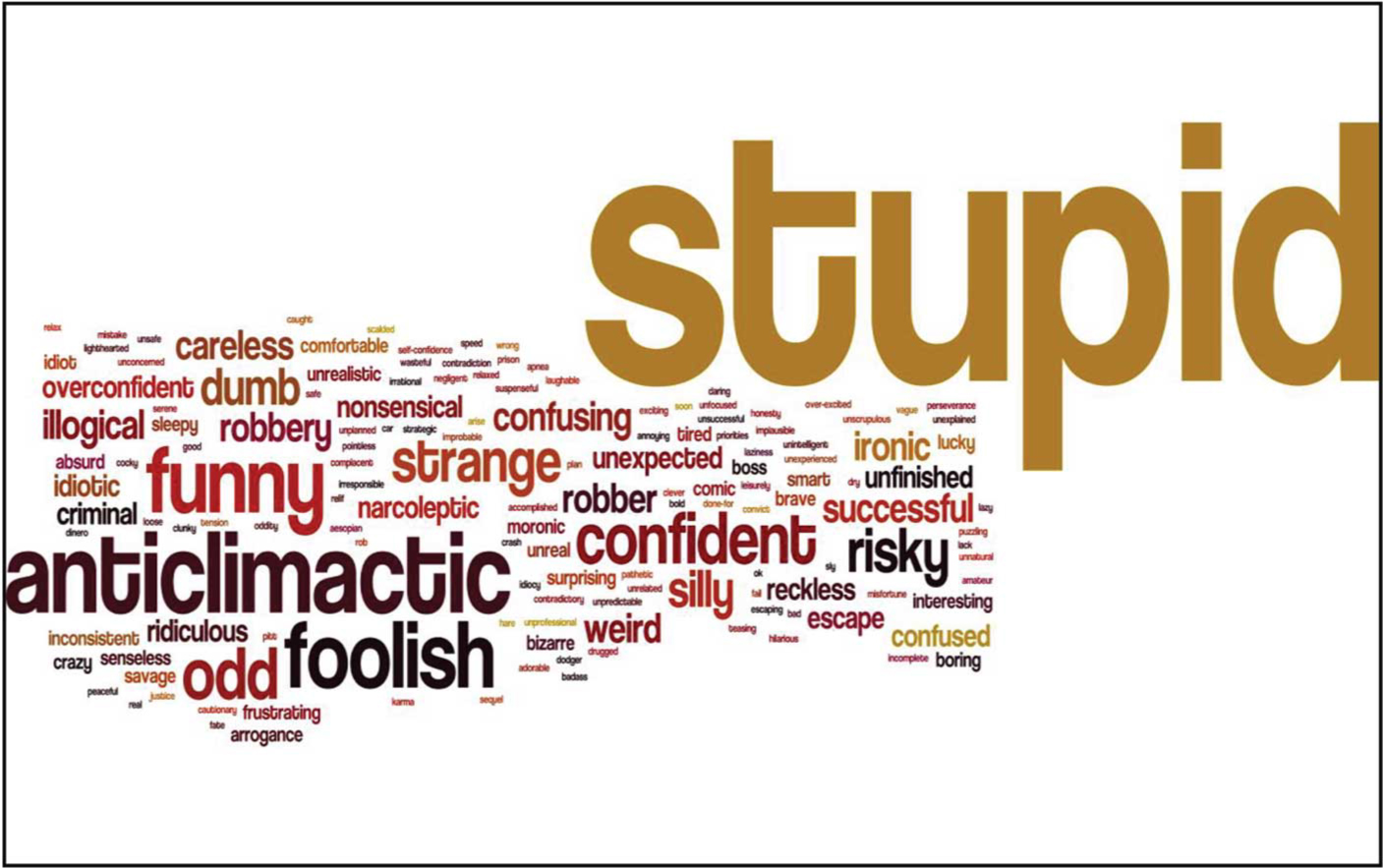

To generate a visual display of the convergence in response

touched upon above, Figure 2 is a

word cloud that captures all 321 one-word responses to the third story in

the survey.

Figure 2.Single word reactions to Story 3: Fire

Brigade.

In this and the other word clouds that follow, the variants

“irony” and “ironical” have been subsumed into the adjectival form that

dominates the cloud visually, on the basis that, of the three possible

forms, “ironic” was the item most commonly used across the one-word

responses. Based on preponderance, the cloud demonstrates a striking level

of agreement across all nationalities and this includes many informants for

whom English is not a first language. In other words, with only a single

word available to grasp the mishap that befell the luckless fire brigade in

Story 3, the overwhelming bulk of informants instinctively and consistently

draw from the semantic-pragmatic space that is inhabited by the concept of

irony.

While specific numerical data will follow later, it is worth

observing that the orientation to “ironic” renders the other choices barely

visible in Figure 2. The nearest

contenders include “coincidental”, “funny”, “careless” and “stupid”. In

contrast, the word “fire” appears, which tends to recapitulate the

narrative’s subject matter rather than offer an interpretative response.

Although reasons of space preclude the presentation of word clouds for all

six stories, and indeed, of word clouds broken down further by national

grouping, the item “ironic” is dominant, and only markedly less prominent,

in the reactions to the other “ironic” stories; that is, to Story 1:

Anger Management and Story 6: Power

Cut. However, within this preponderance, there are interesting

and nuanced variations around the north American and the UK and Ireland

groups, as the quantified data adduced later will confirm.

Consider how this marked clustering compares to a word cloud

derived from reactions to one of the control stories, such the scenario

involving the bank robber who pauses to sleep during the getaway. Clearly,

the cloud in Figure 3 embodies a

much more heterogeneous set of responses. Visually, whereas the word

“stupid” clearly dominates, many more lexical items make a significant

showing, indicating a much more open-ended set of reactions. Again, some

informants offered a summative recapitulation (“robbery” and “robber”), but

most interpretations converged on the “stupidity” of the protagonist (e.g.

“dumb”, “foolish” or “silly”) or on the seeming pointlessness of the story

proper (“anticlimactic”, “odd” or “nonsensical”). Throughout the data set,

individual free-text comments made for very interesting reading, and to

represent these comments economically, a coding system was developed where

the informant receives a number, based on the chronological sequence in

which each of the 321 completed surveys was received, alongside a

designation of their national grouping. Thus, informant number one hundred

and thirty one from the RoW group is therefore coded as “#113/RoW”. Of Story

4, this informant asks “What happens then?”, whereas #75/UKIre has more to

say: “Mr Smyth is an idiot. Either floor it to the border, or hide”.

Orientating towards the “dispreffered outcome” aspect of the story discussed

earlier, #171/NA says the “[s]tory lacks finality but reader might supply an

ending” [sic, here and passim], while the

acerbic #200/NA, using irony of their own, remarks: “Cool story–you

should tell it at parties. … (sarcasm)”. It is worth noting that this

overall pattern of response is replicated for Story 5:

Vacation, which is the other story where the

character’s actions contradict their purported goal. Here, the item

“contradictory” dominates while other popular choices include “unexpected”,

“strange”, “nonsense” and “confusing”. Again, there is some thematic

replication (“vacation” and “holiday”), while seven informants actually

offered “ironic” as their single word response. On this last choice, it is

noteworthy that the item “ironic” appeared at least once in all six sets of

responses, and this is an issue that will be discussed later.

Figure 3.Single word reactions to Story 4:

Robbery.

There remains one story that has yet to receive attention.

This the story of Ms Smyth’s wedding plans and the subsequent rainy wedding

day. Figure 4 displays the

relevant word cloud. As it turns out, the predominant single-word response

is precisely that supplied in Ed Byrne’s skit on Alanis Morissette’s song

(above); that is, that rain on your wedding day is simply

unfortunate. Other entries in the cloud supplement this

interpretation, through near-synonyms like “unlucky” and “disappointing”.

Most informants therefore see no paradox in Story 2, nor

any of the potential irony-generating conceptual oppositions embodied in

Stories 1, 3 and 6. Again, some thematic replication occurs, as in “wedding”

and “marriage”, but overall, these responses do not tell the whole story.

For a start, some informants offered “lucky”, interestingly in opposition to

its slightly more dominant negated variant. The free-text comments offer a

clue: informants point out that in some cultures, like Italy and Brazil, it

is good luck to have rain on a wedding day. #3/RoW says that “In Brazil

raining wedding day bri s good luck.” while #152/NA offers a personal

account of her own: “It rained before my wedding. And the people told me an

Italian folk saying ‘a wet bride is a lucky bride’”.

Figure 4.Single word reactions to Story 2: Wedding

Day

Aside from these cultural factors, some informants, as the

centre of the cloud shows, do offer the word “ironic” as

their single-word response. The unpacking of this through associated

free-text comments is interesting. Ten respondents (out of the 98 who

offered comments) mentioned the Morissette song by name in their follow-up

comments, as with #4/RoW who remarks: “It makes me remind a musica – Isn’t

it ironic from Alanis Morissette”. Other free-text comments hint perhaps

playfully at the song’s title (“ironic, isn’t it?”). Emerging as something

of a wit, informant #200/NA actually attempts to capture the musical

phrasing of the song thus: “IT’S LIKE RAIIIINNNNNN ON YOUR WEDDING DAY”.

Curiously, allusion to the song did not depend on whether “ironic” had been

offered in the single word space. Having inserted “misfortune” in this

space, #13/UKIre dwells at length in the free-text space on the perceived

non-ironic aspects of the song:

This reminds me of the Alanis Morrissette song, ‘Ironic’ where she sings that irony can be explained as “rain on your wedding day.” It always irritated me because that isn’t irony – just bad luck!.

Amusing as the free-text commentaries often are, they raise

more serious questions about the interface between popular culture and

everyday interpretative strategies. Are the words of a popular, high-profile

singer-songwriter responsible for shaping some of the one-word responses?

Can song lyrics act as a higher-order determinant on the

linguistic-pragmatic inferencing strategies employed by ordinary users of

language? Or more bluntly, have informants used “ironic” for the wedding

scenario simply because Ms Morissette’s song describes it thus? All of this

is probably true to some extent, although this interpretation does not

explain the relatively high incidence of “ironic” in reactions to Story 5:

Vacation, where there is no such informing framework

from popular culture. We will revisit some of these issues in the concluding

section, but to bring this section to a close, it is appropriate now to

“unveil” the statistical breakdown of ironic across all

stories and across all national groupings. Figure 5 comprises a histogram which charts in

percentages all responses that produced the single word “ironic” in the

relevant part of the online survey.

Figure 5.Overall percentage of single-word “ironic”

The histogram’s simple headline message is that, globally,

people “do” irony in some way or another. It also highlights the non-binary

and continuum-like nature of irony processing, where certain situations are

felt to be clearly “more ironic” than others. As predicted, the three

“ironic” stories are displayed as precisely that, although the data shows

that Story 3: Fire Brigade is perceived as the “most”

ironic scenario while Story 1: Anger Management is arguably

the most marginal of the three. To reiterate, when charted against this pool

of over 300 respondents, the perception of irony is variable and is not,

even for Story 3, necessarily the “go to” inference for all

informants. The boundaries around conceptualisations of irony are, moreover,

porous: a small percentage of informants, as Figure 5 shows, claimed irony for the stories that

had been intended as the “control” narratives. Notably, Story 5:

Vacation drew even more ironic inferences than those

for the contested rainy wedding day scenario.

What then does the data say about the central themes of this

chapter? Clearly, North Americans do do irony, but is there

enough in the histogram to sustain a meaningful cross-cultural distinction

between this group and the UK and Ireland group? Reactions to Stories 1 and

6 do suggest a difference, where the incidence of “ironic” in the UKIre

columns is, respectively, 4% and 13% higher. However, the striking column,

which bucks this trend, is Story 3: Fire Brigade, where the

North American group was 8% higher in its rate of ironic interpretation of

the narrative situation. Thus, where Stories 1 and 6 collectively display a

8.5% higher incidence for the UKIre group, this is offset by the 8% variance

in the other direction, as displayed by Story 3’s columns. Moreover, the

possibility that there may be something in Story 3 that promotes a

particular ironic reading for the North Americans (a cultural resonance or

geographical clue, perhaps) is thoroughly nullified because this high score

is matched by a proportional rise in the UKIre group also. That said, the

survey’s results, alongside the free-text comments, did draw attention to

aspects of the composition of the stories and to features of its design that

may require re-modelling. The final section of this chapter deals with such

issues and suggests ways in which the large-scale exploration of (reactions

to) ironic situations may be developed further.

4.Conclusions

It has been the principal aim of this chapter to address and

challenge a popular notion that speakers from North America “don’t do”

irony. The evidence drawn from the survey, with over 300 participants

worldwide, and 169 of them from North America, points to the contrary; that

is, that the findings presented here do not support this folk perception of

a connection between nationality and the capacity to produce and understand

irony. While the results show that there are admittedly some differences in

the degree to which ironic inferences are made, these are too marginal to

make a strong and statistically-significant case at this stage. The one-word

data used as the main part of the survey was also supplemented with

free-text commentaries, and the latter alone would make for a study in its

own right, not least because of the light it sheds on the diversity of the

textual clues that underpin the informants’ responses. Moreover, although

the six stories were rendered down into what was thought to be accessible,

universalistic and context-independent formats, the free-text comments at

times cast some doubt on this kind of design. For example, #18/NA is not the

only informant to comment on the firefighters’ meal when he/she asks of

Story 3: “I wish I knew what chicken goujons were!”. Other informants probed

what they perceived as implicit ideological assumptions in the stories.

Having entered “lesbian” in the single word space for the wedding day

narrative, #121/UKIre entertainingly takes issue with the bourgeois

affectation of the country club scenario presented: “Well, you know, ms then

her friend … but a country club? None of my gay friends would marry there”.

But one of the most significant pointers towards a possible re-think in the

textual composition of the stories concerns respondents’ linking of

characters across the stories in such a way as to place them all in the same

narrative universe. During the experimental design, characters’ names like

“Smyth” and “Jones” were simply intended as generic monikers, acting as

neutral place holders in the stories. It came as a surprise then that many

informants linked these characters across the stories. For instance, several

respondents raised concerns that the bride of Story 2 had made a poor choice

in choosing the somnolent bank robber of Story 4. #88/UKIre writes:

With a fianceé as manically unpredictable as Mr Smyth, I would say rain on her wedding day is the least of Ms Smyth’s worries.

while #183/NA comments:

I hope this isn’t the man Ms Smyth from Story 2 married. If so, poor choices. Also, not the best criminal, is he?.

Clearly, many informants had sought to establish a network of

interrelated stories in the survey and while an interesting interpretative

strategy in and of itself, this search for interconnectedness was not

anticipated at the experimental design stage.

Returning to the data in Figure 5, one of the most important theoretical questions is

what makes one story in the collection more ironic than

another? Part of the answer may, again, lie in composition. The model of

situational irony postulated in Section 2 sets out the generic structures for each of the three

relevant stories in the survey. The core element of Story 3: Fire

Brigade was cast propositionally as “Firefighters put out

fires” which collides with the particular and localised features of the

ironic situation (that is, “These firefighters started a fire”). The most

pithy of the three, this formula also seems the most universally accessible

of the three sets of paradoxes on Figure 1. Alternatively, the abstract components for the

arguably less-accessible anger management scenario, by contrast, take longer

to tease out (“Anger management classes prevent people from doing angry

things”) and although they still satisfy the requisite criteria for an

ironic situation, the results confirmed that this story was less readily

classed as ironic across the sample. Moreover, in the text of Story 3, the

lemma FIRE occurs four times and in three different grammatical

environments, and is further supplemented by the cognate term “ablaze”. This

oversight in textual design may constitute an example of what Nash calls

“the hazard of reiteration” in composition, where a lexical form is

repeated, often clumsily, within close syntactic limits (Nash 1980: 48–49). The inherent paradox of the

situation in Story 3 is thus stylistically more foregrounded than in the

other two stories, making the antonymic contrast easier to access.

Finally, as suggested across Section 3, the data collected in the survey is richer and has

more to offer than can be interrogated fully here. It raises questions about

other variables that might play a part in shaping the results. Whereas the

study asked for self-descriptors of nationality, a future study might bring

ethnicity into play also, although asking informants for a perhaps more

sensitive self-assessment of ethic grouping could prove a challenge. The

survey did, however, collect information on age. Looking at responses from

those born during or after the year 1996 – it seemed somehow appropriate to

use the year the Morissette song was released – yields some interesting

results. This group of younger informants produced, on five of the stories,

irony ratings that were on average 5.1% higher than the ratings from those

born before 1996. This was especially marked on Story 5:

Vacation. In fact, the only story on which this trend

was reversed was (ironically?) the wedding day scenario. It might be that we

are using the expression “ironic” more and more, and with perhaps looser or

more permeable semantic-pragmatic boundaries. The longitudinal study that

this observation warrants must, however, wait for another day.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Diarmuid Kennedy, Senior

Librarian at Queen’s University Belfast, for his invaluable support in

developing this experiment and for his guidance on the use of online

systems. I am grateful also to John Garry, for his advice on the

quantitative aspects of this chapter. I would also like to thank for their

feedback the colleagues who attended various of the conferences, meetings

and symposia at which parts of this research chapter were disseminated, and

especially participants at these universities: Lyon, Sheffield, Nottingham,

Portsmouth, Aix-en-Provence, Liverpool Hope and Manchester Metropolitan.

Finally, I am of course grateful to the 321 respondents

world-wide who completed the online questionnaire and without whose

participation, and often hilarious interpolations, the experiment would not

have been possible.

References

Appendix 1Questionnaire (First Page)

Questionnaire

I am interested in the ways in which people respond to

stories and am currently conducting some research into how we react

to simple, short narratives. I am particularly interested to see if

people in different parts of the world, or people of different

nationalities, react in different ways to stories. I would be

grateful therefore if you would complete the short questionnaire

below.

The questionnaire includes six little stories. After you

read each story, you will be asked for a quick one-word

response. If you feel it is appropriate, you can use the same word

to describe other stories as well.

Later in the questionnaire, you will be asked for more

comments on the stories (if you want to provide them) and for some

information about yourself which will be treated anonymously.

Story 1:Mr. Jones had been ordered by a court to take part in anger management classes. On his way home from one of his classes, he was pulled over for speeding. Mr. Jones verbally abused the police officer and was later convicted for the offence.

If you had to describe story 1 in just one

word, what word would it be? Write it in the box:

Story 2:Ms Smyth had been looking forward to getting married for some time. She and her friend had chosen a fine white dress for the ceremony, which was held on the 3rd of June at a local country club. It rained on her wedding day.

If you had to describe story 2 in just one

word, what word would it be? Write it in the box: