You take an old ham actor like Satchmo, you press

a button and you got yourself a show.

— LOUIS ARMSTRONG

FROM ITS EARLIEST YEARS IN THE great American cities of the North, jazz appeared in venues modeled on two basic prototypes: the dance hall and the vaudeville stage. The dance hall and its cousins— hotel ballrooms, cabarets, and the like—fostered the development of jazz as dance music, vitally supporting the social dance craze that covered the nation, in ever-accumulating waves, from World War I through the crash, the Great Depression, and beyond. This aspect of jazz, the one that provided rhythms uncannily suitable for dancing, flourished primarily through the engines of finely tuned ensembles. From the bands of King Oliver and Paul Whiteman in the 1920s to Benny Goodman and Count Basie in the 1930s, jazz was, par excellence, a music to be danced to. But of course it was also more than that. Long before the swing era, jazz was, in addition, a kind of sonic spectacle—a wonder, an oddity, an exhibition, a freak act—in short, a novelty. This aspect of jazz, the one weaned on a vaudeville stage, drawing laughter or slack-jawed amazement from audiences, flourished primarily through the exploits of inventive soloists. And it is here, with vaudeville, that our account of Louis Armstrong’s Hot Fives, the preeminent solo recordings of the age, properly begins.

It is true that during his formative years, before 1930 or so, Armstrong never played in vaudeville, strictly speaking. Yet the same kinds of venues that presented jazz as social dance music often had a floor show. And for most of his major engagements as an up-and-coming player, Armstrong performed stage routines that would have been indistinguishable from the kind of act he might have done on the Keith circuit. Singing, dancing, acting in comedy sketches, wearing silly costumes, horsing around with the audience—such antics formed an essential part of Armstrong’s nightly routine in Chicago. In addition to embracing the outward forms of vaudeville, he also absorbed the assumptions, values, and aspirations of other show business people of his day. The very language employed to describe early jazz seems to have been borrowed, in many cases, from vaudeville. Slang words like hot, pep, legit, novelty, eccentric, and freak; technical terms like break and stop-time; and notions of high-class and low-class entertainment were all used to describe singers, dancers, and comedians before they were ever applied to jazz. Dave Peyton, the chief music critic of the Chicago Defender, urged bandleaders to become “actors” as well as musicians,1 advice Armstrong took to heart, and not just in the sense that he later made movies. As late as 1966 he described his live concerts in vaudevillian (if not penny arcadian) terms: “You take an old ham actor like Satchmo, you press a button and you got yourself a show”2

We should not be surprised, therefore, to find the young Armstrong’s handlers treating him very much like a vaudeville rookie shooting for the big time. It is often noted, for instance, that when Armstrong opened at the Sunset Café, the owner, Joe Glaser, put out a sign advertising “The World’s Greatest Trumpet Player.” Other accounts have Armstrong’s wife Lil Hardin posting the sign six months earlier, in front of the Dreamland Café, where Armstrong opened in late 1925. Both stories are probably true. In fact, almost every time Armstrong’s name appeared in print in the late 1920s, whether in news accounts or advertisements, it was followed by some version of the tag “World’s Greatest Cornetist” or “Trumpeter.” Although such hyperbolic self-promotion might have offended later jazz sensibilities, it went hand-in-glove with a career in vaudeville. “The big acts all had a catchy handle,” one historian wrote, “to help the public remember them.”3 Thus we have Eugen Sandow, “The World’s Strongest Man”; Dan Leno, “The Funniest Man on Earth”; Lillian Russell, “The Most Beautiful Woman in the World”; and even Harry Houdini, “The Undisputed King of Handcuffs and the Monarch of Leg Shackles.” In this context, Louis Armstrong, “The World’s Greatest Trumpet Player,” fits right in.

I dwell on the vaudeville connection to counter the powerful, almost suffocating mythology of Armstrong as the first jazz musician in the modern sense. In some respects, of course, he was. But while his early playing style profoundly influenced Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge, and a host of later soloists, it is important to remember that Armstrong did not, could not, envision that legacy for himself in the 1920s. Rather, he worked within the tradition he knew, one that foreshadowed some aspects of the jazz of the future but in other respects differed radically from it. The differences relate principally to a vaudeville sensibility in early jazz that cast individualistic solo gestures as manifestations of novelty. The standard line on Armstrong is that he transcended this sensibility in the Hot Fives by playing solos of compelling artistry unencumbered by tricks. Guided by this perspective, most analysts have sought to understand the Hot Five recordings as they would a solo by Lester Young or Miles Davis—as a chorus of improvised lines tied to a chord progression. The problem is, this latter-day paradigm doesn’t always fit Armstrong’s early solos. In fact, some of the most striking features can be better explained by reference to the very show business conventions Armstrong supposedly overcame.

This is particularly evident in “Cornet Chop Suey.” Arguably the first Hot Five record to portend a new future for jazz, “Cornet Chop Suey” can be seen as a harbinger of trumpet virtuosity in the 1930s. To understand the meaning of this record in the 1920s, however, we should consider it within the context of novelty, a stage tradition that sustained virtually all of Armstrong’s cornet-playing predecessors, including his beloved mentor, Joseph “King” Oliver.

The first New Orleans jazz bands to play in vaudeville built on the achievements of earlier generations of stage musicians. Beginning in the last decades of the nineteenth century, musical performers divided into two camps—straight (or legit) acts and novelty acts, also known as comedy, eccentric, trick, or freak acts. Straight musicians performed light classical pieces and sentimental songs on standard instruments, emphasizing techniques and tonal values of the European classical tradition. Novelty began as the domain of less conventionally skilled musicians, but when it became clear that such acts usually brought in more money, many straight musicians switched to novelty as well.4 According to veteran monologist Joe Laurie Jr., novelty musicians needed a gimmick, which usually meant playing odd instruments or standard instruments in an odd way. The Tom-Jack Trio made music by throwing snowballs at tambourines, or by clashing swords and shields together in a fencing act. Tipple & Kilmet played on wheelbarrows, the Transfield Sisters on bottles, and Will Van Allen on knives and forks while eating dinner.5 Meanwhile, players of conventional instruments found their own gimmicks, such as Wilbur Sweatman, who played three clarinets at once, or Toots Papka, who played the mysterious “Hawaiian guitar” with a small piece of steel hidden in his hand.

The public thirst for musical eccentricity made possible the stage careers of early jazz musicians. The Creole Band, the first New Orleans jazz band to perform in vaudeville, joined the Pantages circuit in 1914. Appearing on the scene before their music was even known as jazz, the band specialized in playing standard band instruments in unusual ways, performing “a style of comedy-music all their own,” according to the Los Angeles Tribune:

The very instruments assume new personalities. The staid and dignified bass viol does a tee-to-tum, flaps its wings and clarions a challenge to every feathered chanticleer in the corral. The cornet forgets its ancient and honorable origin and meanders madly through the melody, falsetto, throat and chest register, squeaking like a clarinet with laryngitis, jabbering like an intoxicated baboon, and blaring like an elephant amuck. The clarinet squeaks, squawks and squirms, and the trombone, whose business is clawing, becomes a howling musical maniac.6

If all this weren’t enough, the musicians emitted these bizarre sounds “concurrently,” a likely reference to the collective improvisation of New Orleans jazz. Why would anyone want to hear such a cacophony? Certainly for its comedic rather than its musical value: this was “music made to be laughed at,” declared the Tribune .7 In an industry that cherished comedy above any other value (except money),8 the Creole Band hit the spot.

In simulating animal cries, Fred Keppard, the band’s cornetist, continued a New Orleans tradition of muted novelty playing dating back to the turn of the century. The legendary Buddy Bolden, one old-timer recalled, had “a specially made cup, that made that cornet moan like a Baptist preacher”9 Sugar Johnny Smith, according to Lil Hardin, “played a growling cornet style, using cups and old hats to make all kinds of funny noises.”10 The tradition climaxed in the early 1920s with the masterful playing of King Oliver, who conjured preachers, crying babies, roosters, and so forth, through wah-wah effects with his cornet and mute. In his method book The Novelty Cornetist (1923), Louis Panico, one of Oliver’s white “students” and the star soloist of Isham Jones’s orchestra, portrayed these devices as expressions of humor.11 Oliver’s own trick playing did not always depend on comedy, but he made the most of every opportunity to get a laugh, especially on his most popular piece, an unrecorded number called “Eccentric Rag.” One night while playing this tune he made Bob Shoffner, his second cornetist, the butt of a racially charged joke. “Joe was quite a guy and he would love to kid a lot,” recalled clarinetist Barney Bigard. “So Joe took his mute—he was a master with that mute—and told Bob, ‘Here’s how a white baby cries: “Oooh, oh, oooh, ohwa,” ‘ from that mute. ‘Now, here’s how you cried when you were a baby, you big black so and so: “Wah, wah, wah, wah.” ’ All the band broke up so they could hardly play, but Bob didn’t see anything funny about it”12

In addition to creating humor, Oliver’s muted playing fulfilled another important objective of the entertainment business: benign deception. Today, the word gimmick carries derisive connotations, especially for jazz, but in vaudeville it represented a positive good if not a professional necessity. The word, which first appeared in print in the Wise-Crack Dictionary in 1926, initially meant “a device for performing a trick or deception,” and may have begun as gimac, an anagram of magic.13 By this definition, Oliver’s gimmicks were the various cups, hats, buckets, and bowls with which he performed his amusing mimicry. This style of playing may reflect the black New Orleans practice of “signifying” on cultural elements for humorous or ironic effect and, long before that, the African custom of using instruments to imitate the human voice.14 Whatever its origins, Oliver’s novelty playing fit into a larger entertainment culture in the North that prized mimesis, parody, and illusionism. From magicians and mind readers to male and female impersonators to a multitude of “ethnic” performers (portraying Jews in sallow greasepaint, Irish in red, Sicilians in olive, Negroes in blackface, and so forth),15 vaudeville thrived on coaxing audiences to suspend disbelief, or at least go along with an appealing fantasy. Even though Oliver performed in cabarets like Dreamland and the Lincoln Gardens rather than on a bill at the State-Lake Theater downtown, his baby cries and farm animal sounds stemmed from the same impulse to beguile audiences with artful deceptions that inspired such leading stars as Julian Eltinge, the wildly popular female impersonator.

Oliver’s most celebrated ruse in the jazz literature, however, had nothing to do with mutes. The key gimmick here was Armstrong himself, working as an accomplice. In 1922, shortly after Armstrong arrived in Chicago to join Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band at the Lincoln Gardens, the two cornetists stumbled onto a novelty act that musicians would discuss for decades afterward. At the end of an ensemble passage, Oliver and Armstrong would play a harmonized duet break for two measures. Because the breaks changed constantly, it appeared that Oliver was making them up on the spot—which meant that Armstrong must have been telepathic: how else would he know what to play as a harmony part? The two cornetists cultivated this mystery by developing a system in which Oliver would surreptitiously cue Armstrong just a few bars before the break. As Armstrong recalled, “While the band was just swinging, the King would lean over to me, moving his valves on his trumpet, make notes, the notes that he was going to make when the break in the tune came. I’d listen, and at the same time, I’d be figuring out my second to his lead. When the break would come, I’d have my part to blend right along with his. The crowd would go mad over it!”16 The trick would not have worked had Armstrong not had terrific ears and lightning reflexes, but mind reading, at least, was not required.

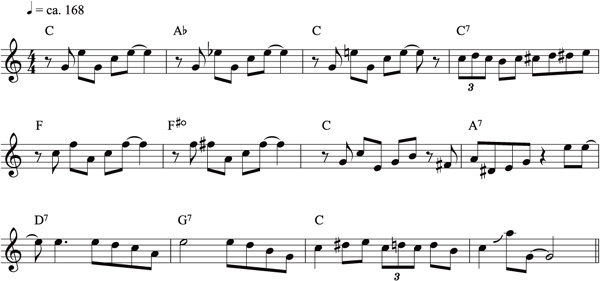

Oliver’s “Snake Rag,” recorded 6 April 1923, provides an example of how this routine worked in practice, even in the recording studio. Oliver gives his cue four bars in advance, and then at the break plays the same riff while Armstrong plays parallel thirds below (example 1.1). As this example indicates, the cue was a shorthand version of the actual break, which probably means that by this time they had developed a fund of more or less rehearsed breaks that Oliver could spontaneously choose from in the course of performance.

EXAMPLE 1.1 King Oliver and His Creole Jazz Band, “Snake Rag,” 6 April 1923, third chorus of the trio, duet break featuring King Oliver and Louis Armstrong.

Despite their obvious kinship with other kinds of vaudevillian sleight-of-hand, the duet breaks were different in one important respect: the trick made sense only to musicians. When Armstrong said “the crowd would go mad over it,” he probably meant (primarily) the phalanx of professional white musicians that crammed the area in front of the bandstand night after night.17 While laypeople on the dance floor might have delighted in the novelty of a harmonized duet in place of the expected solo break, the illusion of Armstrong’s telepathy would have been largely invisible to them. As we shall see, such catering to musicians, such fashioning—in essence—of a novelty for elites, would mark Armstrong’s own music as well.

Thus immersed in the novelty world of the great King Oliver, to whom he looked up as a kind of surrogate father, Armstrong initially set out to follow in Oliver’s footsteps. In particular, he tried to master the muted techniques favored by Oliver and every other major jazz cornet soloist in the North, including Fred Keppard, Louis Panico, and Paul Mares in Chicago, and Johnny Dunn, Joe Smith, and Bubber Miley in New York. The only problem was that Armstrong didn’t have the knack for muted playing. No matter how hard he practiced Oliver’s famous wah-wah solo on “Dippermouth Blues,” he couldn’t get it right. “And I think it kind of discouraged him,” Lil recalled, “because Joe was his idol and he wanted to play like Joe.”18 Well, he did and he didn’t. From a practical standpoint it made sense to try to learn muted techniques, since they represented the well-worn path to success. At the same time, his failure to do so may have provoked not just discouragement but also a sense of relief, liberating him to pursue a course more suited to his natural instincts, one he had in fact been following already for years. It is a course best understood as the path to “Cornet Chop Suey.”

In an interview from 1951, a journalist played the Hot Five recording of “Cornet Chop Suey” and asked Armstrong to comment. Armstrong said nothing of the Hot Fives but, waxing nostalgic, said the record reminded him of his time as a teenager, “when we played the tail gate (advertisings) in New Orleans.… We kids, including Henry Rena—Buddy Petit— Joe Johnson and myself, we all were very fast on our cornets.… And had some of the fastest fingers anyone could ever imagine a cornet player could have.”19 In Armstrong’s mind, “Cornet Chop Suey” stood above all for fast fingers—the mastery of intricate figurations with which he and his friends competed during cutting contests in the streets of New Orleans. The young players knew their sheer volubility marked a break with the past. One of them noted proudly that the older generation of cornetists didn’t play a lot of notes, preferring instead to “linger” on the blues.20

Late in life Armstrong elaborated in a surprising manner on the inspiration for those fast fingers. As a young cornetist, he said, “I was like a clarinet player, like the guys run up and down the horn nowadays, boppin’ and things. I was doin’ all that, fast fingers and everything.… I’d play eight bars and I was gone … clarinet things; nothing but figurations and things like that.…Running all over [the] horn” As “prima donnas” charged with decorating the upper reaches of New Orleans ensemble texture, clarinetists provided a powerful model for ambitious young musicians. We know that by the late 1910s Armstrong had memorized on the cornet well-known clarinet parts to “High Society” and “Clarinet Marmalade,” probably to mine them for material that he could use in cutting contests with his friends.21 By volunteering that he had played “clarinet things” in his youth—especially when no critics or historians had yet made that charge—Armstrong was also admitting that this was no accidental or unconscious appropriation; rather, it had been a deliberate gambit on his part, a conscious effort to distinguish himself by playing in a nonidiomatic style. In taking this step Armstrong forged his own brand of novelty, one that would serve him well when his muted technique fell short.

Armstrong composed, notated, and submitted “Cornet Chop Suey” to the Library of Congress as a copyright deposit on 18 January 1924, fully two years before recording it with the Hot Five.22 Thus, the piece properly belongs to the apprenticeship period of Armstrong’s career, when he was still playing second cornet for King Oliver. Although the recording varies slightly from the copyright deposit, it retains enough of Armstrong’s original conception to appear somewhat anachronistic within the context of the Hot Fives generally, and of his rapidly evolving solo style in 1926 in particular.

Armstrong recorded “Cornet Chop Suey” near the end of the first wave of Hot Five recordings, a debut that produced ten sides in late 1925 and early 1926. On 12 November he launched the series with three records: “My Heart,” “Yes! I’m in the Barrel,” and “Gut Bucket Blues.” On 22 February he added “Come Back, Sweet Papa.” In musical substance and historical interest, these stand as mere throat-clearing exercises alongside the recordings of 26 February, a session that produced “Georgia Grind,” “Heebie Jeebies” “Cornet Chop Suey,” “Oriental Strut,” “You’re Next,” and “Muskrat Ramble” most of which would become traditional jazz standards.

In the absence of contemporary reviews, it is difficult to know how these records were viewed at the time of their release. Perhaps the most suggestive evidence comes from advertisements in the Chicago Defender. The ads portray the records as, above all, music for dancing. Thus, “Cornet Chop Suey” and “My Heart” are “two fox trots as hot as the Chicago fire. Your feet just must go.” Similarly, “Muskrat Ramble” is “a fox trot that makes you just up and dance!” Other hints lean toward comedy. The ad for “Big Fat Ma and Skinny Pa,” recorded later that summer, extols both danceable and comic virtues of the music: “There’s a world of amusement in store for you, when you hear Louis Armstrong sing this comical tune.… You won’t know whether to let your feet do their stuff—or just sit down and shake yourself with laughter.”23 Though not advertised as such, “Heebie Jeebies” must have appealed on comedy grounds as well. Featuring Armstrong’s (and history’s) first extended scat solo—a true vocal novelty—the record provoked Bix Beiderbecke to laugh out loud when he first heard it.24 Likewise, the verbal banter of “Gut Bucket Blues” and mild bawdiness of “Georgia Grind” seem as much designed to tickle the funny bone as to set feet in motion.

Against this backdrop of dance and comedy music, “Cornet Chop Suey” stands out. If the ad billed the piece as dance music, that’s probably because the OKeh marketing team didn’t know what else to do with it. Though no less a creature of novelty than the scat solo on “Heebie Jeebies,” Armstrong’s playing on “Cornet Chop Suey” is clearly not meant to be laughed at. Despite the lighthearted character of the ensemble passages, Armstrong’s studious opening cadenza strikes a serious tone (example 1.2, mm. 1–4). It is possible this seriousness was meant ironically, in funpoking emulation of concert hall rituals, or through the absurdity of juxtaposed opposites: the sober solo introduction followed by the joyous opening ensemble. Lil Hardin’s classical piano introduction to “You’re Next,” recorded the same day, might have served a similar purpose. But this comparison only underscores the imposing nature of Armstrong’s introduction. Like Hardin’s virtuoso passagework, it was meant to impress. Armstrong himself emphasized the concert hall overtones in “Cornet Chop Suey” when he said, with evident pride, that it “could be played as a trumpet solo or with a symphony orchestra.”25

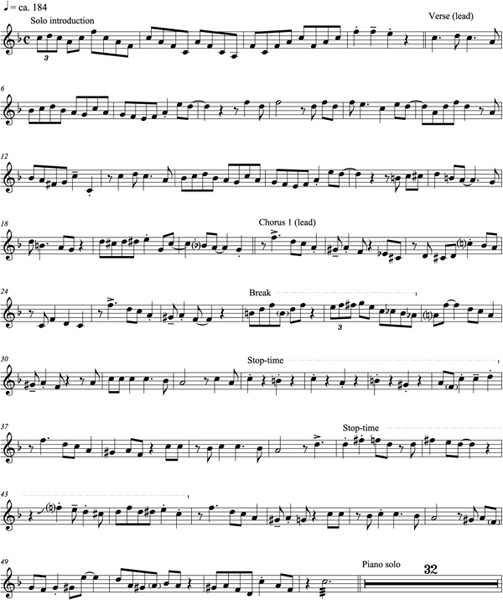

EXAMPLE 1.2 Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five, “Cornet Chop Suey,” 26 February 1926, cornet part.

All of which highlights the biggest difference from the other records, one often noted in the literature: “Cornet Chop Suey” is a showcase for Armstrong’s cornet. Only two other recordings from this early batch— “Oriental Strut” and “Muskrat Ramble”—feature cornet solos of any significance. And “Cornet Chop Suey” goes well beyond these in the extent of the solos. The title of the piece seems relevant here. In choosing it, Armstrong may have signaled not only the prominence of the cornet but also the special nature of his innovations. As a teenager, Armstrong memorized the highly animated clarinet part to the B section of “Clarinet Marmalade.”26 The similarity of this piece’s title to “Cornet Chop Suey,” with the parallel instrument-food construction, is striking. Could it be that Armstrong composed “Cornet Chop Suey” as a sly tribute to “Clarinet Marmalade” complete with honorary clarinet figures?

Like other showcases, “Cornet Chop Suey” is organized to highlight the soloist. The piece consists of a sixteen-bar verse followed by a thirty-two-bar chorus unusual for its lack of a bridge: AA′A″A′″. The chorus breaks down further into eight four-bar phrases, with the first phrase (a) acting as a kind of refrain that alternates with clearly contrasting phrases (b, c, d) that often feature the soloist:

A a (4)

a′ (4) (last two measures: stop-time break)

A’ a(4)

b (4) (stop-time solo)

A” a (4)

c (4) (stop-time solo)

A “ a (4)

d(4)

Outside the verse-chorus form, Armstrong calls for opening and closing cadenzas and a sixteen-bar stop-time solo after the piano chorus (mm. 85–100). Finally, in the recording (but not the copyright deposit) Armstrong repeats the chorus after the sixteen–bar solo, this time as an embellished lead amid the polyphonic statements of his colleagues on the front line (mm. 101–32). Whereas in the first chorus Armstrong stays close to the notation in the copyright deposit, in the second he seems to be improvising an imaginative paraphrase of the melody. In this sense the second chorus also assumes the character of a solo, albeit an accompanied one.

Laden with solos, “Cornet Chop Suey” certainly looked to the future, but it is possible to overstate its progressive attributes. Copyrighted in early 1924, the piece is downright old-fashioned in some respects. Such Hot Five recordings as “Muskrat Ramble” and “Big Butter and Egg Man” feature complete solo choruses accompanied only by the rhythm section, anticipating modern practice. But “Cornet Chop Suey” emphasizes the limited openings characteristic of the ragtime generation: breaks and stop-time. Even the extended middle solo does not represent the kind of open “blowing space” that would become customary in later jazz. Instead, it has a chord progression different from both verse and chorus and, like the shorter openings, is in stop-time. In the notation Armstrong wrote “patter” over this solo, a fascinating annotation in this context. In the 1910s and 1920s many Broadway songs added a patter section as a third strain after the verse and chorus. Initially inspired by the patter style of singing in Gilbert and Sullivan, a popular song patter often required rapid repeated notes or a degree of rhythmic complexity in the vocal part. In dance band arrangements, a patter played the same structural role while replacing the singing with some kind of ensemble feature over stop-time accompaniment.27 In the patter to Fletcher Henderson’s “How Come You Do Me Like You Do?” (1924), for instance, a clarinet trio holds forth in stop-time. It was this type of instrumental patter, adapted for soloist, that Armstrong employs here. Needless to say, patter solos would not figure prominently in the future evolution of jazz.

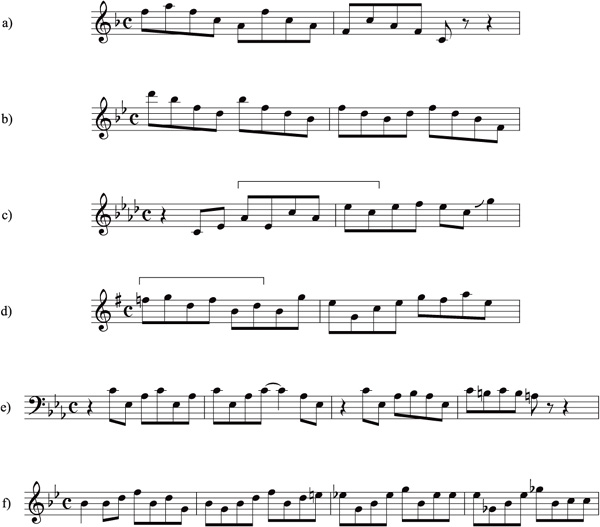

It is important to grasp the traditional, even stodgy framework of “Cornet Chop Suey” in order to properly interpret the influence of the clarinet in Armstrong’s playing. To be sure, running eighth notes suffuse the piece with the spirit of clarinet style. But the most self-conscious clarinet references, the ones that sound almost like quotations, appear in the brief solo spaces mentioned above: the introduction, coda, breaks, and stop-time passages. In these solos Armstrong often employs arpeggios in sawtooth patterns, a hallmark of New Orleans clarinet style. This figuration abounds in recorded clarinet solos and obbligatos, uniting the otherwise disparate playing of such distinguished performers as Lorenzo Tio Jr., Johnny Dodds, and Sidney Bechet. In its prototypical form, the sawtooth figuration appears as a series of ascending or descending broken chords separated by jags (example 1.3a–b). If a player wanted to increase the energy of the line, he could double the number of jags by cutting the chords in half (example 1.3c–d). To decrease the tension, clarinetists sometimes used a circular version that kept returning to the opening note (example 1.3e–f). This static figure dominates Benny Goodman’s famous “Clarinetitis” (1928) and formed the basis of the well-known saxophone melody of Glenn Miller’s swing-era standard, “In the Mood.” (It also provided the basis for Kid Ory’s “Muskrat Ramble,” a fact that supports Armstrong’s long-standing claim to have composed the piece, given his interest in clarinet figures at this time.)

EXAMPLE 1.3 a) Lorenzo Tio Jr., “Bouncing Around,” 3 December 1923, transcribed by Charles E. Kinzer; b) Johnny Dodds, “Buddy’s Habit,” 5/15 October 1923; c) Sidney Bechet, “Cake Walking Babies (from Home),” 22 December 1924; d) Johnny Dodds, “Potato Head Blues,” 10 May 1927; e) Lorenzo Tio Jr., “Lou’siana Swing,” ca. 18 February 1924, transcribed by Charles E. Kinzer; f) Johnny Dodds, “Buddy’s Habit,” 5/15 October 1923.

Armstrong’s solos with King Oliver reveal a preoccupation with clarinet figurations, which he undoubtedly acquired in New Orleans and brought with him when he came North. On “Chimes Blues” (1923), his first recorded solo, Armstrong fashions two blues choruses around a constant reiteration of the “In the Mood” riff (example 1.4). Another solo from the Oliver period, “Tears” (1923), consists of a series of arpeggiated breaks, most of which exhibit variations of either the classic sawtooth pattern (mm. 3–4, 7–8, 15–16) or the “In the Mood” riff (mm. 27, 31, 33–34) (example 1.5). The third break, the most striking and original of the group, represents an ingenious adaptation of the sawtooth design by filling the jags with ascending triplets (mm. 15–16).

EXAMPLE 1.4 King Oliver and His Creole Jazz Band, “Chimes Blues,” 6 April 1923, Louis Armstrong’s solo, first half.

EXAMPLE 1.5 King Oliver and His Creole Jazz Band, “Tears,” 5/15 April 1923, Louis Armstrong’s breaks.

“Cornet Chop Suey” copyrighted just three months after “Tears,” multiplies the clarinet references while restricting them to particular moments. The opening and closing cadenzas reveal clarinet style most clearly (example 1.2). As others have noted, the piece begins with a quotation from “High Society,” the clarinet test piece that Armstrong memorized in New Orleans. The rest of the introduction consists of a cascade of sawtooth arpeggios in classic clarinet style (mm. 1–4). Armstrong begins with descending figures, then, after reaching the bottom of his range, changes direction and ascends, thereby extending the sawtooth pattern for a full three measures. In doing so, he goes beyond the practice of clarinetists themselves, who ordinarily confined this figuration to one or two bars before switching to another pattern. Armstrong’s prolonged adherence gives the line a studied, exaggerated quality, making it, in effect, a parody of clarinet style. Such naked referentiality returns at the end, where Armstrong links two distinctive clarinet figurations—a descending secondary rag pattern (mm. 136–38) followed by the sawtooth arpeggios of the introduction, now ascending to a final, sustained high A.

Clarinet figures in the patter fit into a fragmentary rhetorical scheme encouraged by the stop-time setting. Armstrong presents the solo in clear two-bar phrases marked off by caesuras, sustained notes, and distinct changes in melodic character. The first phrase has the nature of a syncopated bugle call or fanfare (mm. 85–86). The second, in running eighth notes, provides contrast (mm. 87–88). The third phrase, in turn, contrasts with the second, this time through sawtooth arpeggios in clarinet style (mm. 93–94). And the fourth echoes the opening bugle call while ending the entire eight-bar passage with a bluesy cadence (mm. 91–92). The fifth phrase returns to clarinet style more emphatically by stating the “In the Mood” riff three times in succession, thereby doubling the length of the phrase (mm. 93–96). And the sixth and seventh phrases present fluent eighth-note lines that might have been played on clarinet but do not betray the style directly (mm. 97–100). Like the opening and closing cadenzas, the two obviously clarinet-like passages in the patter are conspicuous but transient.

In a similar way, during the melody of the chorus Armstrong uses clarinet figurations only during the solo breaks. In the first break he links the “In the Mood” riff (m. 27) with the beginning of the third “Tears” break mentioned earlier (m. 28; cf. example 1.5). Armstrong plays the next two stop-time passages straightforwardly, as melodies, not solos (mm. 33–36, 41–44). When he returns to these passages in the second chorus, however, he treats them soloistically. The most obvious clarinet reference appears in the last stop-time passage, where he presents a modified sawtooth pattern broken up by eighth rests (mm. 123–24). Tellingly, both stop-time passages begin with vaulting arpeggios, but the figurations do not evoke clarinet style very strongly (mm. 113–14 and 121–22). As we shall see in chapter 3, these examples seem to be part of a transitional phase in early 1926 during which Armstrong was struggling to create an acrobatic style less reliant on the clarinet.

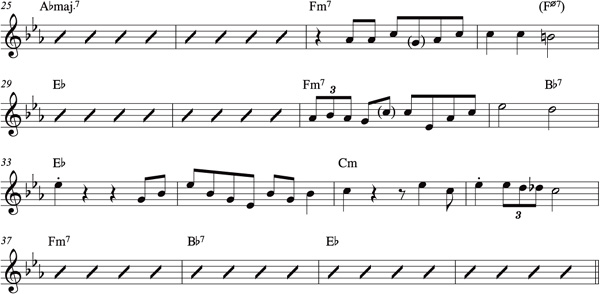

The most transparent clarinet figurations in “Cornet Chop Suey” allow us to guess at Armstrong’s intentions. By confining such direct references to brief openings, Armstrong appears to view clarinet style not as a language to be adopted wholesale, but as a gimmick, a vivid momentary diversion—like Oliver’s wah-wah effects—with which he could capture fleeting attention in the evanescent manner of all novelty artists. And yet a comparison of the copyright deposit with the recording also suggests mixed feelings on Armstrong’s part, as if he may once have aspired, however inchoately, to co-opt clarinet style in toto. Like other lead sheets, most of his copyright deposits from the 1920s show a simplified, skeletal version of the tune as recorded.28 But, with few exceptions, the notation for “Cornet Chop Suey” is actually more complicated than the lines Armstrong played on the recording two years later. In particular, the former contains several running eighth-note passages that Armstrong simplifies— and often clarifies—in the latter (example 1.6). By comparison with the still very dynamic recording, the copyright deposit seems almost frenetic. A sometimes awkward quality in the notated lines (e.g., mm. 91–92) suggests that Armstrong was straining for effect, perhaps to convey a relentlessly clarinet-like virtuosity. That his take on the piece changed after two years suggests not only a maturation in his ideas but also, perhaps, a disaffection in his view of clarinet style in the purest sense.

EXAMPLE 1.6 “Cornet Chop Suey,” a comparison of eighth-note passages in the copyright deposit with their simplified versions in the recording.

As for the more direct clarinet references that remain in the recording, these were an anomaly by 1926. After he moved to New York in 1924 to play for Fletcher Henderson, Armstrong continued using clarinet figurations in breaks on “Go ‘Long Mule,” “Shanghai Shuffle,” take 2 (both 1924), and other pieces. In subsequent years, however, overt “clarinetisms” would gradually drop out of Armstrong’s vocabulary, to be replaced largely by more integrated acrobatic melodies that yet bore traces of the clarinet’s early influence. In this context, “Cornet Chop Suey” occupies a unique position. Boasting more clarinet figures—both actual and implied—than any other Armstrong solo, this recording represents the peak of his interest in clarinet style.

In taking up clarinet style Armstrong found his own brand of musical subterfuge, charting a course not far distant, in principle, from the faux human and animal cries of Oliver, Keppard, Bolden, and the rest. This point brings us back to his friends in New Orleans. When Armstrong moved to Chicago and made good beyond anyone’s expectations, one of his old sparring partners back home expressed frustration and resentment at Armstrong’s success. Guitarist Danny Barker tells the story:

Kid Rena was the king trumpet player, and his six-piece band was acknowledged the best in town. On this Sunday afternoon he stood up in the truck and blew his best, but Lee Collins played a half-dozen tunes which were currently popular on records by Louis Armstrong. These trumpet solos were considered phenomenal at the time. Lee stood up in the truck and angrily blew in the direction of Kid Rena Cornet Chop Suey, When You’re Smilin’, Savoy Blues—he blew his solos exactly as on the records.29

Overwhelmed by public enthusiasm for Armstrong’s music, Rena lost the contest. Unbowed, he criticized his former rival, taking particular aim—if his language is any indication—at “Cornet Chop Suey”: “And because Louis was up North making records and running up and down like he’s crazy don’t mean that he’s that great. He is not playing cornet on that horn; he is imitating a clarinet. He is showing off.”30 Rena’s accusation that Armstrong was imitating a clarinet has the ring of a heckler unmasking a magician— “He’s got it up his sleeve!”—as if the act of imitation somehow diminished Armstrong’s achievement. Rena’s point, apparently, was that Armstrong’s most dramatic lines in “Cornet Chop Suey” were not as original as they sounded, and he was right. In that sense Armstrong was a magician, creating the illusion of strikingly fresh cornet lines when in fact he had borrowed them from another instrument.

Unfortunately for Rena, it didn’t matter that Armstrong was “only” imitating a clarinet, because for listeners who recognized that fact the feat itself trumped originality. Plenty of instruments—strings, woodwinds, and keyboards especially—could be made to execute clarinet-like arpeggios with ease. But arpeggios are difficult to play on brass instruments because the move between chord tones often requires subtle adjustments in embouchure, wind column, and oral cavity instead of the simple depression of a finger key. Classical pedagogies aimed at correcting the inevitable problems of delivery, but few black cornetists had access to the training usually needed to acquire such skill. And none of them—from the early 1920s, at least—used arpeggios in his recorded solos in any way comparable to Armstrong’s rigorous deployment in “Cornet Chop Suey.” As Rena alleged, Armstrong was indeed showing off. Yet his stunt may actually have been most impressive to other musicians, who recognized the idioms. Like Oliver’s duet breaks, the act of playing like a clarinet represented an elite kind of novelty, one that required an insider’s perspective to fully appreciate.

In his peculiar take on novelty, Armstrong embraced an aesthetics of difficulty that set him apart from his predecessors. Dave Peyton, Armstrong’s most consistent chronicler in the 1920s, seems to have recognized this shift. He still used the old words to describe him, preferring the term eccentric to the alternatives novelty, trick, or freak. But Peyton could see that Armstrong offered a new kind of eccentric playing based more on difficulty than on comedy, more on figuration than effects. Commending Armstrong’s “weird jazzy figures,” Peyton noted that Armstrong “brought us an entirely different style of playing than King Joe [Oliver] had given us.” For Peyton, the new style represented a cultural advance toward sophistication, artistry, and proper training. “The style of jazz playing today requires musicianship to handle it,” he wrote in 1928. “The beautiful melodies, garnished with difficult eccentric figures and propelled by artful rhythms, hold grip on the world today, replacing the mushy, discordant jazz music [of the past]”31 Of course, the “difficult eccentric figures” adopted by so many cornetists and trumpet players in the late 1920s had been pioneered largely by Armstrong.

In taking up the clarinet idiom and then extrapolating from it a more generalized acrobatic manner, Armstrong separated novelty style from comedy and redefined it for a new generation—one that quickly outgrew the novelty label. By the late 1930s, “Cornet Chop Suey” no longer stood for clever vaudeville tricks. To the contrary, New Orleans trombonist Preston Jackson saw the record as a foretaste of modern jazz, going so far as to equate it with the proto-bop pyrotechnics of trumpet star Roy Eldridge. “There’s Cornet Chop Suey,” he said. “Listen to the record and listen to Roy’s records and compare them.”32 In a similar manner, Armstrong himself connected the figurations of his early years with bebop. “I was crazy on doing a whole lot of fancy figurations, like what they call bop today,” he recalled in 1966.33 By then vaudeville was a fading memory, and even Armstrong associated his daring youthful exploits with what followed them rather than with what came before.

In the 1920s, the progressive connotations of “Cornet Chop Suey” may have tied in to race politics and the new spirit of dignity and self-respect that moved through the black community. This connection is symbolized in Armstrong’s evolving relationship to King Oliver. As a guardian of tradition, Oliver disapproved of his protégé’s new style, urging him to “play the lead, boy, play the lead [i.e., the melody], so people can know what you’re doing.”34 Oliver claimed that it wasn’t seemly for a cornetist to abandon his role as bearer of the melody to chase abstract “variations,” but that was probably not his main objection. As Thomas Brothers has shown, Oliver himself had been known to replace the melody with variations on occasion.35 More likely, Oliver felt the ground moving under him and couldn’t help trying to suppress the coming earthquake. Feeling the same tremors, Lil Hardin did everything she could to intensify them. Marrying Armstrong scarcely a month after he copyrighted “Cornet Chop Suey,” Hardin formulated an ambitious campaign to engineer her new husband’s rise to success. As we shall see in subsequent chapters, her plans involved not only exposing to the world his dazzling natural talent but also reinventing him musically and socially to meet higher cultural standards. Believing that Oliver wanted Armstrong in the Creole Jazz Band so he could neutralize him as a threat, Hardin urged Armstrong to leave. As Armstrong himself probably recognized, it was time—in more ways than one.

Hardin began her rehabilitation project by weaning Armstrong off his old-fashioned New Orleans clothes and dressing him in the latest northern styles. Although he initially resisted her efforts, this transformation carried tremendous cultural resonance for him. Indeed, shortly after arriving in Chicago two years previously, he had been primed for a makeover by the experience of seeing the stage act of dancer and showman Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Armstrong wrote years later that “the sharpest Negro man on stage that I [had] ever seen in my life” lived up to all his expectations: “He had on a sharp light tan gabardine summer suit, brown derby and the usual thick soul [sic] shoes in which he taps.…His every move was a beautiful picture”36 Just a few months earlier, Bert Williams, the greatest star of black vaudeville in the 1910s, had passed away. Robinson represented a new generation of black stage artists, one that replaced minstrelsy stereotypes with a more dignified and classy performance image suitable to the New Negro of the 1920s. Robinson’s progressive style struck Armstrong as an advancement for African American society in general. “To me [Robinson] was the greatest comedian + dancer in my race. Better than Bert Williams.” Why?

I personally admired Bill Robinson because he was immaculately dressed—you could see the quality in his clothes even from the stage Stopped every show. He did not wear old raggedy top hat and tails with the pants cut off, black cork with thick white lips, etc. But the audiences loved him very much. He was funny from the first time he opened his mouth till he finished. So to me that’s what counted. His material is what counted.37

As a performer who “didn’t need blackface to be funny,” Robinson was free to dress in a dignified manner, letting his “material”—his actual routine—do the entertaining for him.

As Gary Giddins has written, Armstrong drew inspiration from Robinson’s example.38 To extend this line of thinking, it appears that Armstrong occupied a similar historical position in relation to Oliver as Robinson occupied vis-à-vis Bert Williams. The style of novelty cornet playing exemplified by Oliver and his contemporaries, nurtured in comedy, was the sonic counterpart to the “raggedy top hat and tails with the pants cut off.” Musicians marveled at the subtleties of Oliver’s technique, but audiences mostly appreciated his humorous imitation of crying babies, roosters, and so forth. When Armstrong poured out runs and arpeggios with unprecedented rhetorical force, it was as if the New Orleans sound had been clothed in an immaculate tuxedo, complete with white cane and gloves. Rather than eliciting laughter, Armstrong drew awe and eventually adulation. In this respect he, too, embodied the New Negro ideal. The occasionally self-deprecating, “lowdown” effects of Oliver and his generation reminded of a repressed and humiliating past. Armstrong’s clean, agile, flashy style retained black idioms (e.g., swing and the blues) while demonstrating an instrumental prowess previously associated with white players. For all of his own commitment to good old-fashioned novelty, Armstrong thereby sounded a call to the future, a call never before more urgent than in the cascading arpeggios that introduce “Cornet Chop Suey.”