CHAPTER 6

The tension between modernity and reality

1945–2010

In international opinion polls, Sweden shines as one of the world’s most secularized and rational countries.1 The rapid changes in the second half of the twentieth century took a country that was a distinctly rural society and transformed it into a modern, urban welfare state. The rapid break with the past was partly impelled by the general public’s faith in a rational, enlightened, and well-designed state. The motors of change were the increasingly intricate welfare policies combined with a concentrated effort on harnessing industry’s drive, in which agricultural policy was a cornerstone of the welfare state edifice. As the Swedish nation-state became increasingly drawn into the global supply system, its agriculture was to face enormous challenges in which historical circumstance may well prove crucial for its future development.

In the middle of the 1930s, the degree of urbanization in Sweden was 35 per cent, while no less than 30 per cent of the population was occupied in agriculture. Compared with western Europe, Sweden, together with the rest of Scandinavia, appears strikingly rural; an impression compounded by the fact that much of Swedish industry–forestry, mining, and the timber and manufacturing industries–was raw-material based and located in rural areas.

While much of Europe was reduced to rubble in the Second World War, Sweden had stood on the sidelines, and began the post-war era with its population and infrastructure intact. Both economic and social circumstances lent themselves to a strong, politically led modernization; indeed, Sweden’s welfare state was shaped by ideas of modernity. Rational, industrial, and urban were the mottos of the day, but almost as important was the appeal to a sense of community in both the home and the nation as a whole .2 The interweaving of the rational and the emotional was perhaps necessary in a country that went from agrarian to industrial so abruptly. The folkhem (lit. the People’s Home) was a metaphor that even in its initial stages was to prove crucial for agriculture, particularly given the Social Democrats’ interpretation, for it entailed a brand of politics in which family and social policy were mixed with agrarian policy, and ultimately would comprise both strongly conservative and equally strong modernizing elements.3 The question here is the effect general political developments and analogous social, cultural, and economic trends at the local level had on Swedish agriculture.

A country of small farms

In 1944, Sweden was predominately a country of small-scale agriculture, with almost half a million enterprises classed as agricultural units scattered throughout the country. The greatest number was to be found in the most intensively farmed districts, but in the intermediate and forest districts the relative dominance of small farms was even greater. Some 200,000 farms were classed as 2–10 hectares, to which must be added a further 200,000 that were less than 2 hectares–in many cases residential properties, although most of them still had a chance at some measure of self-sufficiency. Only a few per cent of the agricultural units were larger than 100 hectares, and they were limited to the old estates and the iron works situated in rural areas, normally complemented by a large farm.4 The greater part of agriculture was given over to mixed production, in which animal products played a large role, of course, but forestry was also of considerable importance. The farms’ small scale meant that many farmers were largely dependent on other sources of income.5 The Swedish landscape accommodated great variety.

Seen in terms of production, the larger farms played a far more important role than their modest number would indicate at first glance; socially, it was the smaller farms that were the more important, for it was there the bulk of the rural–and agricultural–population lived. Families at this point accounted for some 70 per cent of the total work-force, the rest was annually or seasonally hired labour.6 The dominance of family-based production also meant that there was a gender-based hierarchy of work, which essentially meant that the women’s main focus was animal husbandry, and the men’s was arable and forestry work. At the same time, there was considerable flexibility on the part of the women, who, with the possible exception of forestry, might well find themselves involved in all the work of the farm .7

There was a strong hereditary element in landownership, and thus a greater economic advantage in a farmer inheriting and taking over the running of a family farm than being forced to buy one on the open market. This also meant that at least once in any family cycle there would be elderly parents or other relatives resident on the farm. Most farms were part of a complex system of family and neighbourhood co-operation. Small farms were quite simply incapable of owning all the farm equipment that was needed, while the success of larger projects depended on collaboration across farm boundaries.

The political route to modern agriculture

Much of the agricultural policy that was launched in the 1940s had already been formulated in the previous decade as part of the reformist resolve to improve rural social conditions. The message of modernism and rationalism had begun to find a hearing in the 1930s, but the Second World War intervened, and the most important decisions were deferred; a course of action founded on 1930s’ views on men, women, family, agriculture, enterprise, and ownership was thus first realized over a decade later. The policies that were put in place at the end of the 1940s would resonate for the best part of four decades, contributing to increased production and more stable earnings, but also more rapid rural depopulation, environmental problems, and eventually a considerable production surplus.

The major political event was the adoption by Parliament in 1947 of an agricultural policy based on the Report of the 1942 agricultural committee.8 Both the Report and the government’s proposed law used a number of new normative terms to describe the agriculture they had in mind; amongst them basjordbruk (basic farms, 10–20 ha), normjordbruk (ideal farms, 20–30 ha), and övergångsjordbruk (transitional farms, in development or about to be wound up). By adopting new terminology for existing concerns, it is as if they wanted to free agriculture from its historical encumbrances. Three goals were emphasized. The first, income, meant that the state would maintain agricultural prices so that farmers could enjoy income growth that matched that of other comparable groups: a basic farm ought to generate an income equivalent to the salary of a rural industrial worker. The second goal concerned efficiency, and implied that small, supposedly unviable farms ought to be shut down or taken over by financially strong farming units. The third goal concerned the size of total production and set out to secure domestic supply in the event of war and blockades. It was hoped that Sweden in the long term would run just under complete self-sufficiency.

Small-holdings, which had once been seen as the salvation of the rural population, were now seen as poverty traps and obstacles to industrial development. The ambition was to put effective and technologically modernized agriculture on as stable a footing as possible by promoting a structure of fullständiga jordbruk (lit. complete farms) large enough to fully provide for the farming household and to make full use of its labour, and to transfer labour from agriculture to industry by means of what was called ‘extrinsic rationalization’. The decision showed a clear ambition to redistribute both land and people. The 1942 agricultural committee, the government, and Parliament all believed agriculture was too variform and badly organized, with too many small-scale operations. People were tied to unprofitable farms that broad developments were incapable of modernizing. Instead, the state ought to unleash agriculture’s potential by planning its structure rather than leaving it to chance. Rationalization was the catchword. Its planned outcome would be ‘complete units’, with carefully weighed proportions of acreage and labour, and a work-force that would work effectively and rationally. Liberated from ‘incomplete farm units’, people would be free to meet other socio-economic needs.

The state was given the opportunity to buy the land of smaller farms and to redistribute it to those who had a greater need of it. On the regional level, the lantbruksnämnd (County Agricultural Board) set about putting the ‘extrinsic’ and ‘intrinsic’ rationalization of the farm-holdings into effect. Legislation on acquisitions and the state’s pre-emptive rights brought land purchase under state control. As early as 1945 a special land-acquisition law had been passed, whose principle measure was to limit the right to purchase farmland to the real farming population.9 Industry, corporations, and individual investors were to be excluded from agricultural properties. Agriculture became a matter to be settled between the state and the farmers.10

Parallel with the modernization of farming, in the 1940s Sami reindeer herding was subject to a series of official inquiries and measures that ultimately were meant to result in a rationalization of the scale of its operations. Production was to be increasingly mechanized, and the character of reindeer herding altered, while the restructuring of the Sami villages into formal economic corporations was intended to bring this form of husbandry into the modernist fold.11

Agriculture, pure and simple

Among the policies of the welfare state, all of which were predicated on the just distribution of welfare, there were a number of family policies that had the effect of triggering a redefinition of what constituted an ideal family; a redefinition that continued throughout the intensive decades when the country was transformed from a rural society into a modern industrial nation. It was against this background that another new term was coined for the kind of agriculture the state had in mind: familjejordbruk (family farms), a word given new meaning by political efforts in the 1930s to promote the family at a time of falling population. The word family to most people conjured up distinct associations, often with something traditional such as the mediation of spiritual and material values, of morality and loyalty; yet at the same time it could be described as something modern, as the embodiment of male enterprise, to the lasting benefit of women, children, and ultimately the whole nation. Unsurprisingly the term would be much discussed, and frequently challenged.12

The opponents of family farming on both the Right and the Left pointed to how little ‘family’ and ‘agriculture’ chimed with each other in terms of labour and supply. Various economic experts produced calculations to show that women in existing, household-based agriculture had too much agricultural work–particularly because animal husbandry was their responsibility–to the detriment of the running of the household. Periodically men had too little to do, which could be remedied by enlarging agricultural units, preferably to above the basic farm acreage to something approaching the ideal farm of 20–30 hectares. Politicians sought to distance themselves from what was thought an old-fashioned agricultural problem, namely the lack of demarcation between women’s and men’s responsibilities, and between work and leisure. In the male rhetoric of the official texts, farm-work was too ‘laborious’ and future agricultural production would be so ‘complicated’ that it would require ‘qualified’ workers, while for the same reason women were considered ‘unwilling’ and ‘unable’ to do farm-work. Women in their traditional guise as farm-workers were depicted as becoming obsolete in the future. If only agriculture could be made more profitable, large-scale, integrated, and rational, then men could work the land, and women could cease farming and take care of the household instead.

If agriculture was to develop into a project for male bread-winners, it was essential not only to alter the women’s part of the gender contract, but also to recast men’s behaviour. The tradition of multiple job-holding by men, which occasionally took them far from home, had to cease. The official texts underlined the fact that in future farmers would be professionals, and what was needed were not only clear-cut gender divisions, but also proper definitions of real agricultural labour, hiving it off from other undertakings such as forestry: a passion for homogeneity and rationality that embodies a true modernist approach.

However, both the 1942 government agricultural committee and the 1947 policy concluded that the transformation of the average 10 ha Swedish farm into an acceptable 30 ha farm was a political impossibility, as it would require the nationalization of all farmland. In reality, this meant that the ideal of the housewife could not be fully realized because the small farms survived. Any bid to improve basic farms would continue to depend on women’s work.13

Town and country

One feature that distinguishes the modernist approach is the use of binary terms such as nature and culture, or town and country, as mutually exclusive dichotomies. In modernist thinking, cities and urban life became the idealized norm, while the country was thought of as divergent and old-fashioned. It was from the city’s Olympian heights that rural life was planned and judged–the reverse was unthinkable. In the first instance, the countryside was needed in a modern society in order to supply the city’s inhabitants with food; agricultural policy existed to ensure that those who needed to remain in agriculture would enjoy reasonable social conditions. However, there was another side to modernism in which the countryside had social worth. Too drastic an agricultural policy, too extreme a population shift, and there was a risk of jeopardizing values that could not be measured in money, but that were still of immense importance for the well-being of society. It was recognized that sufficient account should be taken of the value of the agricultural population remaining in rural areas.14

In the countryside, views were rather different. In the 1940s and 1950s, rural areas were generally inward-looking. Agriculture, bound up with hundreds of years of tradition, was the country’s ‘primary industry’, and would remain so in future. It was more than capable of supplying all the country’s needs, while traditional rural values came off well compared with the city’s modern values. True, measures would be needed to make sure the best young people stayed, or, their agricultural education complete, that they returned to take over from their parents. The degree of self-sufficiency was still high, albeit declining, and even if the cities’ factory-made existence was attractive, urbanites still needed food and rural materials from the countryside in order to function. There were countless local rural associations where people met to solve their everyday problems, and to organize courses, dances, and other entertainments. The city was not everything.

The 1947 policy meant in practice an enormous investment to regulate and modernize Swedish agriculture. The reforms were expensive, and required a cadre of state-employed agricultural experts. It is reasonable to ask, although tricky to answer, the extent to which the political initiatives succeeded in their aims.

One important goal was to increase farm sizes to at least the basic farming level, to which end the regional agricultural boards were established to supervise the rationalization, with both politicians and experts represented.15 The plan was that they would direct the agricultural property market so that smaller farms were merged with larger ones. The problem was that the regional agricultural boards only had the power to intervene in land sales, while all land inheritance was governed by the property laws–and most farms were inherited. When a farm was transmitted by inheritance rather than by sale, the regional agricultural board had no authority to determine whether the potential farmer was suitable. The high rate of family conveyance indicates that the farmers did their utmost to keep under the boards’ radar, and at least to some extent checked their rationalizing zeal. The increase in Swedish farm sizes remained minimal, despite the considerable bureaucratic edifice put in place. The extent of the frustration this caused can be seen in some of the political responses in the 1950s, by which time only a few hectares had been added to the average farm size.16 Another important explanation for the low average acreage is that small-holdings continued to spring up in the northernmost counties well into the 1950s, in part because of the promise of extra income from forestry and job opportunities constructing hydro-electric power stations.17

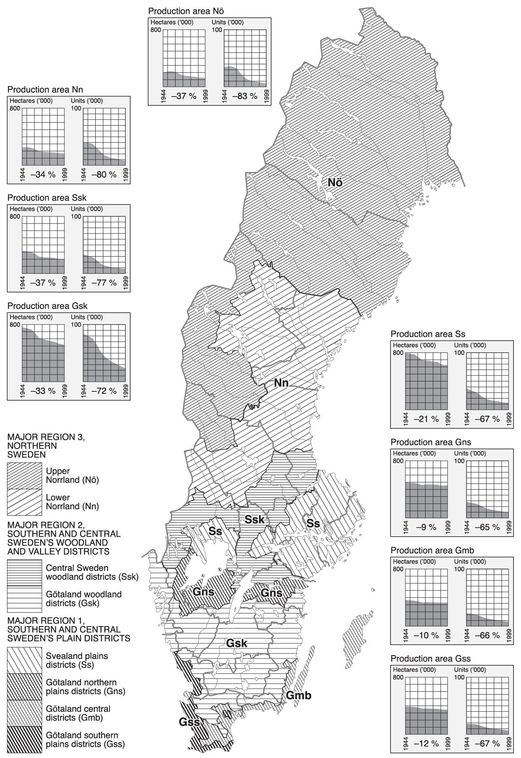

Figure 6.1 Arable acreages and number of agricultural units by region and area, 1944–9. The three official ‘major regions’ and eight ‘production areas’ have been used in official agricultural statistics as the administrative divisions for farmland since the 1910s. Source: Flygare and Isacson 2003, 32.

Even if political rhetoric and bureaucratic practice deemed the creation of larger farming units important, it was within individual farms that the real changes took place. The reasons for this must be sought in the general social changes of the day rather than in agricultural policy per se. Swedish industrial production accelerated after the Second World War, and wages rose rapidly in the early 1950s. It was difficult for agriculture to retain its waged work-force, with the result that the importance of family labour grew. The reduction of the number of waged women had already begun in the 1930s, but in the 1950s the majority of waged men left too. Basic farms, or family farms as they were now increasingly known, became clearer in character in the course of the period, in line with the stated political goals. Yet everyday circumstances dictated that no farm could exist for long without women, which was the simple reason why most male farmers were married, and bachelor farmers depended on an unmarried sister, an old mother, or a live-in housekeeper.18

Dairying was still the economic cornerstone, and something of a symbol for agriculture– and it was still women’s work. Women tended the livestock, and above all took care of the hand-milking. After the war, milking-machines became widespread– one of the century’s most important technological innovations.19 So long the woman’s lot in life, hand-milking was rationalized out of existence, although many women had to hand-strip after milking for a while yet. The milking-machines of the day were heavy, as was all the paraphernalia. Women continued to play an important role in maintaining good dairy hygiene, and everything had to be washed-up by hand in hot water. Nor was there necessarily hot water to be had in the barn. With few women employees, all this work fell increasingly to the housewives. Many women also took over the operation of the milking-machine when the men were busy sowing or harvesting.

The most important technological advance of all was the tractor, which only really began to sweep all before it in 1945. Tractors were very expensive, and at busy times often two or more were needed. The result was that for spring tillage in the 1940s and 1950s it was common to see a tractor pulling the harrow while a horse followed with the sowing-machine. Since throughout Sweden sowing was traditionally man’s work, it was often the farmer himself who followed the horse, while the tractor and harrow was driven by his wife, or possibly one of their sons or one of the older men.

The 1940s and 1950s also saw the rise of chemical farming, strongly advocated by agricultural experts, and heralded by intensive advertising in the agricultural press. Sales of inorganic fertilizers and biocides soared.20 Fertilizer had to be spread separately. The handling of seed-corn and fertilizer sacks was heavy work, since they all had to be shifted by hand. The harvest of winter fodder followed a few weeks later, with only a short window to bring in the hay if it was to be of reasonable quality. After the war, most farmers made their hay using mowing-machines or windrowers, and racked it up to dry. Haymaking engaged the entire household, and many farms had to bring in extra help for the few crucial days. When the hay had dried, it was pitch-forked from the hay-drying racks on to a cart, for stacking in hay-barns and hay-lofts.

Since nearly half the Swedish acreage of grain was harvested with reaper-binders, this meant that threshing followed some weeks or months after harvesting. Harvesting grain with a reaper-binder and tractor involved broadly the same steps as in the days of horsepower. Since unthreshed grain must be stooked to dry, it required physical strength and more hands. In general, the whole household took part.

The women’s working day was usually longer than the men’s, partly because on top of their work with the livestock and in the fields, the women were also responsible for running the household. A considerable amount of the women’s energy went in holding down the farms’ running costs. Housework thus entailed a far greater variety of tasks than it does today. Even if the social ideal par excellence in the 1950s was the housewife, most farms lacked both the financial and practical means to realize it. Women themselves set great store by working outdoors since they received more appreciation for that than for their housework, to which the men rarely paid much attention .21

Neighbourhood co-operation redoubled

Starting in the late 1920s there was considerable activity on the part of the economic and trade-union movements at the national level, with Riksförbundet Landsbygdens Folk (National Federation of Rural People, or RLF) and Sveriges Allmänna Lantbrukssällskap (Sweden’s General Farming Society, or SAL) in the lead (see p. 209) Alongside these formal organizations, an extensive local system emerged of informal job rotations, joint ownership, and collective farming that was occasionally put on a formal footing.22 This collaborative approach peaked in the 1940s and early 1950s, dwindling in importance thereafter as agriculture was modernized, its place taken by the national co-operative and trade-union movements, with their ever greater influence on the corporative nature of the Swedish Model. In the shift from the premodern to the modern, local forms of informal and formal association had had great importance, and they were to regain it in postmodern society.

Women and men

THROUGHOUT HISTORYTHE organizational unit of most Swedish agriculture has been the household. A household’s primary goal is to secure its long-term survival, and this work engages all its members–adults and children, women and men. The lower the technological level, the more the available hands must be put to work. A household is not a homogeneous body, however, but individuals grouped by generation and gender, and–in ages when households also had servants– class.

Little is known of the relationship between the sexes in prehistoric agriculture, and our understanding of it rests on archaeological remains and anthropological analogies. One interpretation is that with the advent of the ard in the Bronze Age, agriculture was vested with male prestige. Harvesting with sickles was something both women and men did, it seems. Cattle and herding belonged to the male sphere, while women were responsible for goats, sheep, and small animals. It seems likely there was a shift in the gendered division of labour when, in the late Iron Age, agriculture began to resemble what we know from later recorded history.

During the Middle Ages, dairy cattle, and above all their butter, became economically important. Butter production was women’s work, and was probably the cause of male jealousy, glimpsed in the belief that women by magic could make a rival farm’s cows dry, while the milk flowed from their own cattle. The strong taboo against men milking had old roots–it is mentioned as early as the Icelandic sagas, and it would live on well into the twentieth century. This was important because Swedish agriculture had become so concentrated on dairying. Butter matched cereals in its substantial economic value, and women and men can be said to have answered for two different production lines, with the men taking the lead in the arable farming. This did not mean there was an absolute division of the sexes. Men participated in certain stages of animal production, apart from the milking. Women had their given roles in the fields and in fodder production. The gender order was especially evident on the summer farms, from Dalarna northwards. With the intensive transhumance of sheep, goats, and cows, these regions had the opportunity to participate in the strong economic development of agriculture from the middle of the eighteenth century. The summer farms were strictly the province of women.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the production of fresh milk became all the more important with increased urbanization. On large estates the work-force included entire families, and the women’s role was to milk the big herds of cows. Even family farms and small-holdings were drawn into commercialized dairying. It was only with the rise of the mechanized milking-machine in the 1940s that milking became a primarily male occupation.

The post-war period brought a dramatic fall in the agrarian population, especially among the men and women who previously would have been employed in agriculture. At the same time there was a determination on the part of politicians and society at large to create professional agriculture–with the male farmer in focus. With a dwindling work-force, only the farmer and his wife were left on the farm, and while they still divided the work between them, collaboration was key. Dairying profitability was falling, and there were fewer and fewer dairy farms. With the advent of a national health system and care for the elderly in rural areas, women were able to hold down part-time work alongside farming. Soon enough, many men found themselves in the same situation.

The situation today is contradictory: where the trend is towards large arable units, it is often only men who are involved; but when it comes to animal production, women’s participation remains steady. It is noticeable how often the herders employed on the farms are young women with degrees from agricultural college. Similarly, both women and men are to be found running the small agricultural businesses designed to supplement household incomes.

In an agrarian society, the right to own land gives access not only to the necessary resources but also to power and status. As early as the Viking Age, rune-stones show that both women and men had the right to inherit and own land in Sweden, and this was later maintained in medieval legislation. Inheritance law stipulated than men should inherit twice as much as women, and this only changed in 1845, when both sexes were given equal rights of inheritance, and indeed equal matrimonial property rights. Right up to the end of the nineteenth century, male heirs took precedence in choosing their share of any land. However, families in a position to subdivide their landholdings were only too happy to provide their daughters with land, not least because it promoted favourable marriage alliances. Women like men had a ‘rights of lineage’–they could reverse the sale of land to a third party if they could prove kindred with a previous owner.

Yet even if women could inherit and own land, they still had no right to control it unless they were widows. By marrying, the husband became the wife’s legal custodian. Formally, women could not buy, sell, or mortgage land. It was men, in their capacity as landowners, who could appear in the local courts where land disputes were settled, and it was men who had the right to join in running the village. Even if women in practice could manage a farm, they lacked all the legal rights to decide over their property.

Until the Marriage Act of 1920, the husband had the right to administer his wife’s property–a right retained until 1950 for marriages contracted before 1921. Given that it was relatively late in the day for women to be acquiring individual property rights, it is perhaps not so surprising that for agricultural properties men in practice still take precedence when the time comes for a generation shift. The only real exception is forestry, where women in recent years have taken a more prominent role.

How best to understand the immensity of the changes neighbourhood co-operation entailed? One approach is to view it as a bridge between two societal forms. It hastened the pace of agricultural modernization, but also contributed to the preservation and adaptation of traditional modes of life to the new conditions prescribed by the government and Parliament. It assuaged some of the concerns in farming quarters that they were not staying abreast of events, and that traditional values were being overturned in the wave of modernization. And it seems that any differences between the local, largely informal system of neighbourly support on the one hand and the national, formal co-operative movement on the other in time resolved into complementarity and interplay.

There are several possible reasons for the growth of neighbourhood co-operation at the end of the 1920s. One was the difficult economic and social situation, compounded by both the growing labour shortage and the poor prices agricultural produce commanded. On top of this were the new implements and machinery that steadily poured onto the market. Any farmer who wanted to stay in business had to have some sort of connection to an economic co-operative if he was to sell his produce or have a chance at the new technology. And that technology was expensive. For those working small and medium-sized farms, the solution was neighbourhood co-operation.

Such collaborations also had a social dimension, for they went further than produce and technology, and through the educational and cultural activities that evolved alongside created the prospect of meaningful spare-time in rural areas. Adult educational associations gave young men and women the opportunity to improve their theoretical and practical skills. If they were active in the youth associations Svenska Landsbygdens Ungdomsförbund (the Swedish Countryside Youth Association, or SLU) or Jordbruk-Ungdomens Förbund (Federation of Young Farmers, or JUF), as many of them were, they were schooled in social activism and political work. Here co-operation served the ends of modernization, although with varying results. Some young people now had access to the implements they needed to be able to take over and modernize their parents’ farms, but most of them seem to have been inspired to look elsewhere, and to continue their studies to obtain better-paid jobs with more regular hours that would give them greater leisure.

Despite mechanization, Swedish agriculture in the 1930s and 1940s continued to rely on a sizeable work-force. Farms without sufficient labour of their own, or without the finances that permitted them to hire labour, had to depend on their neighbours and relatives. Hired help was kept for the busiest periods, or when a horse or farm equipment had to be hired. Neighbours and relatives were called in at slaughter and other infrequent but labour-intensive tasks. By taking on another farm’s wood-cutting, for example, a family could be certain of help in return. The ways and means were many, and the informal exchange of labour was no doubt far more extensive than contemporary sources reveal.

Men’s co-operation revolved around implements and machinery mostly, or avoiding having to work at monotonous tasks alone; women were obeying the same unwritten rules when they met at a relative’s, or gathered to cut strips of rag for rugs, to card, weave, sew, and wash, or worked together to watch one another’s children.

In the villages, the adults would help with major repairs or the construction of new buildings. Such work was often rounded off with a party. The sources make particular mention of sharing labour at threshing, sowing, and lifting root vegetables. Neighbours turned out to help because they knew they would receive help in return when they needed it. A few days before the work was due to begin, a couple of families might meet to discuss it over coffee. The church green was another place where many such deals were struck. Relatives could be called on at short notice. Practical skills of a more specialized kind–carpentry, joinery, concrete-pouring, painting, and weaving–were much sought-after. Work was paid back with work. These exchanges were very common, for no normal-sized farm would have survived without the efforts of relatives or neighbours. In areas with lots of small-holdings it was particularly in evidence, and it operated between farmers in the plains of southern and central Sweden–although it was not found everywhere. Older farmers who participated in the major initiative around 1990 to collect farmers’ reminiscences noted that other than their immediate family, neighbourhood co-operation was either weak or non-existent in their particular district.23

Even in mechanized and ever-more rational post-war agriculture, there was a need for collaboration on all levels to cope with everyday tasks, especially when it came to larger building projects. The political ideal, however, remained that of the basic farm making its own way, which was supported by the way mortgage policies were shaped.

Joint ownership and the joint use of machinery and tools could be regulated in the form of an association with articles and meetings, but also more informally between two or three neighbours. The latter was a convenient way to manage large investments and repairs as long as the participants could agree on costs and the exact form of the items’ use. Of the machinery that was owned and used jointly, the most common were sowing-machines, threshers, reaper-binders, and manure-spreaders.

The interest in co-operating over agricultural machinery was unsurprisingly weakest on the largest farms. After all, this kind of co-operation had–and has–its problems. Above all, the opportunity for the individual farmer to do his work at exactly the right moment was considerably reduced. Farmers with large acreages needed certain access to functioning machines when the weather was favourable. On the other hand, joint ownership and joint use not only meant that individual farms’ costs were reduced, but also that the equipment was put to greater use, and more farms had access to the new technology.

A total of 14,700 associations of all kinds were registered in Sweden in 1930, of which 10,000 were agricultural, a number which continued to rise. In addition, there were numerous small, more informal, collaborations of the type just described. Amongst the associations needed to manage investment and maintenance, the small, locally managed electric associations deserve special mention. Their importance for the modernization of rural areas cannot be stressed enough.

Threshing associations were common. The threshing itself was often done by a team of men. In some cases, one of the association’s members, the so-called ‘motorman’, was paid to do the threshing. The rules of the association laid down how the threshing was to alternate between farms. The aim was to reduce waiting times to a minimum, and threshing was only stopped for rain. Any surplus was spent on repairs and the purchase of new machinery.

At the start of the 1930s, the government launched an official inquiry to consider proposals to make the joint ownership of agricultural machinery easier for smaller farms. In its Report of 1937, the inquiry recommended the setting up of a state loan fund from which associations of farmers and individual contractors could borrow money to purchase machinery. The contractor would then be paid to do the work at the various farms. This kind of equipment fund survived with a few small alterations until 1967, but in the 1950s and 1960s was overshadowed by capital investment loans to individual farmers. The state and the local agricultural associations initially supported individual contractors, men who bought machines using state machinery loans and then were hired to work by farms in their district. From about 1950, the state started to push for more advanced machinery pools. Money from the machinery loan fund was lent by the local agricultural associations to individuals or associations to buy farm machinery to be used jointly by several farmers.

After 1950, the machinery associations went into steep decline. It was now far more common to hire individual contractors, who were sometimes farmers themselves, but often not. Most contractors were found in southern Sweden. The commercial machinery pools began to find life more difficult, and to survive had to specialize. The circumstances for such specialization were particularly favourable in Skåne and Halland. Beet- and potato-growing required expensive farm machinery that was difficult for small farms to finance. In these areas, the machinery pools had a stable circle of regular customers.

The co-operative ownership of machinery and tools was not limited to agricultural production per se. Wash-houses and saunas, which became increasingly widespread in the early 1930s, were often joint-owned. They were run as clubs, but had often been set up at the instigation of the local authorities. To help farming housewives there were also bakehouse clubs, mangling groups, and weaving circles. They had a double function, since they reduced the capital outlay required of each household and promoted contact between the district’s inhabitants. They were also a channel for new technology and new thinking in the initial stages of modernization, when the farms alone could not bear the costs.

As well as machinery associations, there were also livestock associations, which were at least as important for the modernization of agriculture. Part of their aim was to limit the costs of individual farmers, but their primary purpose was to improve the quality of livestock breeds, and so increase meat and milk yields. The county agricultural societies were the driving force, not least thanks to their peripatetic district foremen. Bull associations were common, later to be replaced by artificial insemination associations (see p. 193).

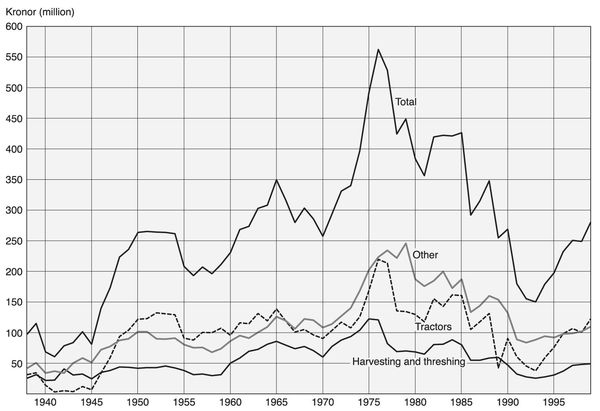

Figure 6.2 Investment in agricultural machinery and implements, 1938–99 (in 1950 terms). Source: Flygare & Isacson 2003, 175, 379.

Horse insurance associations were also widespread. Their members were recompensed if a horse disappeared, died, or had to be put down because of illness. Indeed, the list of livestock associations was a long one. There were special groups for practically all imaginable animals and purposes. Some associations had a great many members, were extremely active, and were associated with district or national leagues. Others were small, locally limited operations. There were breeding associations for horses, pigs, sheep, and cattle; associations for milk-testing, eggs, hens, and livestock insurance; slaughter-house, purchasing, and marketing associations; those for soft fruit and fruit-growing, grazing, seed-cleaning, pasture, handicrafts, mills, stone-crushing, and hoof-care; and farmers’ associations such as the forestry owners’ association. Together, all these associations and co-operatives for machinery, implements, animals, crops, and buildings give the impression of febrile collective activity at a time when industrial society was growing ever stronger, and traditional agrarian lifestyles were in decline and under immense pressure to change further.

The industrial ideals of the 1960s

By the end of the 1960s, there had been a series of crucial changes in agriculture. The numbers it employed had dropped to 12 per cent, and by 1966 the number of farming units of more than 2 hectares had fallen to 186,000, compared with 300,000 in 1944. It was still dominated by small-scale farming: 100,000 farms still had less than 10 hectares, while nearly 60,000 had 10–30 hectares. The remaining units were predominantly of the order of 30–50 hectares. The geographical distribution was largely unchanged, with the larger farms in the best cereal-growing areas, although these were the same districts with the largest number of small farms. The average farm size was now approximately 16 hectares, compared with the 12 hectares of the 1940s. Twenty years after the great post-war agricultural reforms there were signs that the hoped-for ‘basic farming’ was now nearly in place.

The slow pace of change was a source of irritation in some circles, and the trade unions, industry, and representatives of the Social Democrats all called for a new concerted agricultural policy. The remit for the ensuing government inquiry was formulated in the late 1950s, when economic and technological development was rapid, and belief in the future strong.24 In its reports, agriculture was depicted as obsolete and out of step with the times, and its work-force stuck with poor working conditions; dynamic social change demanded that agriculture’s transformation be hastened. Relocation grants and farm conversion subsidies should be introduced so that people could abandon farming, and to ease the transition from farming to other occupations. The very ownership structures were thought to be a brake on the transition to large-scale production and efficiency. Restrictions on corporations and industries acquiring land ought to be removed, and the state’s pre-emptive purchase rights strengthened. In terms of agricultural policy, modernization now took a very different direction from the scientific and rational principles of the 1940s. Rationality in the 1960s was almost exclusively equated with large-scale production and industry.

The farmers were infuriated and disheartened by turns. In Parliament their representatives, outraged by the ingratitude of it all, fought back. Having bowed to the politicians and implemented their rationalization of farming for two decades or more, their thanks, the farmers said, was to be described as a burden on society.

Families, businesses, and farmers

Much of the political conflict boiled down to the issue of ownership. Should anyone be allowed to buy land, or should farmland be protected from industrial and corporate capital? In the political discussions of the 1940s, familjejordbruk (lit. family farms) was a term used to describe the labour supply on individual farms, not the ownership structure as such, which instead was denoted by the term bondejordbruk (lit. peasant farms). In the 1960s, in discussions about land-acquisition legislation, however, the term bondejordbruk was carefully avoided by the government agricultural committee, and in their proceedings they used terms such as family farms or ‘real farms’ whenever they were forced to be precise. Its opponents, on the other hand, for political reasons used terms such as bondeägd (lit. peasant-owned), bondejordbruk, or bondebruk (lit. peasant farm), deliberately harking back to the old legislation and old terminology. If agriculture was described as bondejordbruk, a case could be made for it including forestry, echoing the existing term bondeskog (lit. peasant forestry); the term family farm was problematic, since familjeskogsbruk (family forestry) did not exist as a term, even if some hardy souls subsequently tried to launch one. The workings of Swedish idiom meant that forestry seemed less of an agricultural concern, and the growing idea of ‘true’ agriculture went unchallenged.25

The future of agriculture was said to lie in business, since that was a neutral organizational form. The business model was held up as economic and efficient, competitive, and rational–a far cry from family farming. To support family farming was to support the creation of special privileges for a fixed professional group; whereas the Government Report of 1966 (SOU 1966:30–31) argued that farming ought not to be a hereditary profession, and in future farmers ought to be managers rather than workers. The categories the proposal pitted against each other were thus ‘farming business’ and ‘family farm’. There were two very different political notions at work here. The Right argued that the policy should concentrate on family farms, while the Left found it impossible to subscribe to the principle of family farms, and argued that agriculture should be thrown open to all.26

The repression of women

In the 1960s’ description of farming businesses, both actual and future, the silence on the role of women was deafening. The reality of 16 hectares of semi-mechanized mixed farming worked by men and women alike evidently had no place in the ideals of the 1960s. Instead, modernization was modelled on working conditions and gender distribution at a handful of very large farms, piggeries, and broiler farms. A number of statements made by the Right, however, accorded women a more emancipated role in the actual day-to-day farming.27 In a society in which both women and men were wage-earners, family farming could create job opportunities for both spouses. However, the whole rhetoric of agriculture as a business tended to gloss over the physical work involved in farming, whether it was done by women or men.

Small-holdings and part-time work seemed to bring out the worst in all the pundits. Descriptions of part-time farming and small-holdings blithely assumed there would be one man and one woman (a wife) working the agricultural unit, the man gainfully employed elsewhere during the week, the woman working the fields, or busy in the barns with animal husbandry or some form of special produce. According to their–male–interpreters in Parliament, girls thought this work held as little appeal now as it had done twenty-five years earlier. Accounts of such agricultural work showed that it took up all the women’s working time, yet it was still the man’s waged labour that determined whether the farm was classified as a part-time farm. However much farming may have been a full-time occupation in a woman’s perspective, it was still the man’s daytime occupation that determined the farm’s classification. 28 It is also interesting that there were lingering reminders of women having to work in ways that were unacceptable in a modern society, to the extent that the idea of agricultural modernization seems to have been based on the repudiation of women’s productive efforts. Certainly by extension there was a sense that rationality was a quality solely possessed by men.29

Town mores, country mores

When the decision about the new agricultural policy was to be taken in 1967, there was far greater awareness of the larger picture–famine, the over-exploitation of natural resources, the plight of humankind in the modern age. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) had caused a stir in Sweden, and voices were heard challenging the policy of modernization; as early as 1967 a specific government body, Naturvårdsverket (the Environmental Protection Agency), was established under the Ministry of Agriculture; and in the mid 1960s the question of a looming global food shortage had already been raised by Georg Borgström in The Hungry Planet.30 It was hardly to be expected that agricultural policy could fail to be affected by such currents, and the discussion reflected a countrywide shift in perspective. Even though the modernization of agriculture proceeded unchecked, it became increasingly difficult to describe the future of high-capacity industrial farming in the innocent terms used by the minister of agriculture in a parliamentary debate in 1967, when he artlessly referred to the successful land reclamation on the Soviet steppes.31 The professed rationality of the course set out in the 1940s rapidly evaporated when the collected force of the environmental arguments imposed new modes of expression. Visualizations of Sweden’s open landscape or descriptions of stressed city-dwellers evoked very different agricultural values. Even if in practice the scale of agriculture grew, there were fewer farmers, and the countryside was more heavily cultivated. It was as if descriptions of the conditions of large-scale production had become too instrumental and rational. In the discussion of agricultural policy in general, and more specifically of the attempts to counter the proposed new land-acquisition law, an argument was formulated that set biology, health, and culture against what was seen as a policy of farm closures, economies of scale, and industrialization.

All the existing forms of farming were drawn into a general representation that was to have great importance for future policy. Agriculture was described as part of a biological system and an open landscape. Methods of production and forms of ownership all became part of the argument for the conservation of nature, the preservation of culture, and the open landscape. When the modernizers described agriculture as little more than the primary producer in the food production chain, they threatened an ecological and cultural public resource.32

Although inroads were being made into the dominant, rationalist approach, the polarization between town and country increased. Farmers were under growing pressure to modernize and comply with what city-dwellers needed. The rural areas and their inhabitants existed primarily to supply the cities’ needs for raw materials, food, and labour. Gradually, as leisure time grew, new housing estates were more compact, and real incomes rose, there also needed to be holiday cottages and good roads so that the city-dwellers could escape to enjoy the relaxed atmosphere and abundant gifts of the countryside. The Lantbrukarnas Riksförbund (Federation of Swedish Farmers, or LRF), financed by farmers’ membership dues, set out to use its publishing house, information campaigns, and magazines–of which Land quickly became Sweden’s largest weekly–to market modern agriculture and country ideals in a period when environmental issues were coming to prominence, and more and more city-dwellers looked to the countryside for their recreation.

Between ideal and reality

The question remains of the extent to which modernizing political ideals actually had an effect. In order to attain the desired rationalization in size, more stringent demands were made of potential farm-owners. Many county agricultural boards regularly exercised their pre-emptive right of purchase to restructure existing farms. This meant that if two farmers were interested in acquiring the same neighbouring property, the county board decided which was in greater need of strengthening his existing farm. As far as possible farmers used the exceptions made for relatives, assuming that there was a relative willing to take over the farm. The desire to bring about the widespread industrial ownership of farmland became little more than wishful thinking, bar a handful of farms owned by the tinned-food industry, partly because industry itself was doubtful–owning the entire production chain from ear of wheat to packaged loaf did not strike many as particularly rational–partly because rural landownership structures spoke against it. It was a lengthy process for an industrial company to buy up a series of properties and consolidate them into a single large estate.

More often than not developments were contradictory. Some farms grew in size and operation, while others went the other way and were converted into part-time farms. The increase in the number of part-time farms must be seen as a failure of post-war policy, which had planned for economically sound farms, each supporting a family.

That ever fewer people were employed in agriculture can be explained by Sweden’s rapid industrial expansion. Industry was also undergoing sweeping changes as it became increasingly concentrated in the cities, and the emphasis on large-scale industry became clearer. Where once it was the countryside that was industrialized, now there was an ever-stronger division between an agricultural countryside and industrialized towns. In less than a decade, Sweden’s many small, timber-built towns were engulfed in blocks of flats and high-rise buildings, the town centres swept aside to make way for department stores and car parks. The ambitious housing scheme to build one million housing units, the so-called Million Programme (1965–75) soon left its mark on Sweden’s towns. Sweden’s rural population increasingly moved to the towns, and for each new high-rise built, a pasture somewhere else was left to be overgrown with weeds and brush.

There was a general sense that agriculture did not offer much in the way of opportunities, and amongst farmers there was very little belief in the future. They hesitated to invest, and farmers’ average age increased. The number of employees dropped further because the average agricultural wage could not compete with industrial wages, with the knock-on effect that family labour became even more important, which, with the rise in average ages, meant that farming couples worked ever harder while their children left the farm altogether, or at least found other work. Narrative sources show that it was in this period women’s work shifted from being reasonably independent to a supporting role as the men’s assistants. Farmers’ wives in the 1960s became farm-hands on their own farms.33

Meanwhile, by the end of the 1950s production had begun to show signs of a shift away from milk production, particularly in arable areas. Even if mixed farming still dominated, there were further blows during the 1960s. On smaller farms with smaller herds it was often more profitable to sell the cows and find odd jobs in industry–a familiar first step towards part-time farming. If the farm was larger, pig-farming was frequently an attractive prospect, and the family could continue to support itself by farming. Where farmers chose to stick with milk production, the size of the herds grew, and milking was mechanized even further, with milking-tubes, bulk tanks, and refrigeration units. Much of the heavy work in milking disappeared. This period saw a general modernization of barns and stables. Wooden barns were demolished and replaced with new, concrete constructions, while old stone-built barns were complemented with new equipment. The regional agricultural boards supplied farmers with both favourable loans and construction drawings. Despite all this, the sources show that animal production on a family farm was still labour-intensive. It required both the farmer and the farmer’s wife, and in many cases would have been impossible if there had not been an older generation on the farm, to be gradually replaced by adolescent children. These families had little spare time.

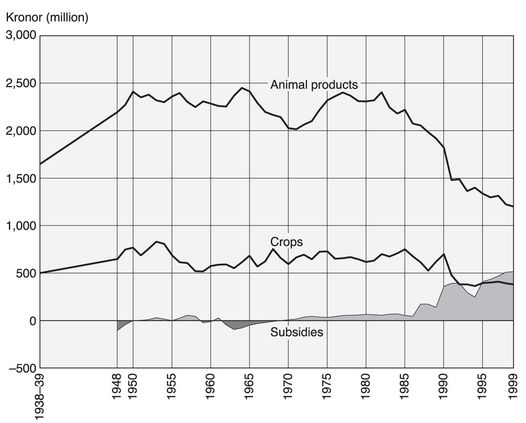

Figure 6.3 Total income from agriculture, 1938–99, by animal products, crops, and direct government subsidies, including EU subsidies from 1995 (in 1950 terms). Source: Flygare & Isacson 2003, 106, 377.

Where the trend was towards increased cereal cultivation, however, an old farming problem became acute–the seasonal imbalance in the work-load. Larger acreages of arable combined with a dwindling supply of seasonal labour drove the further mechanization of these farms, where the most important improvement was the combine harvester. The first combine harvesters had been built to cope with smaller, and definitely dryer, harvests than the Scandinavian climate offered, and their future in the region was dependent on improvements to mechanical drying. Agricultural associations began to build grain dryers, and now someone from the farm was detailed to drive the grain from the farm to the dryer as quickly as possible. The combine harvester was pulled by a tractor, and on the actual combine the farmer’s wife, son, or perhaps father stood tying the sacks of grain and dropping them to the ground as they progressed across the field. Many farms experimented with drying systems in which cold air was blown through grain spread out on the floor; others built warm-air dryers, initially wood-fired. Once combine harvesters had grain tanks, handling changed completely because the grain remained loose. Shovelling and working the screw to transport the grain to the dryer increasingly became the work of women, boys, or older men.

If cereal production was intense at the height of the season, there were periods in between when the time had to be filled with other activities. Most Swedish farms had at least some forestry. Even if it varied in size, it was a source of both work and income that is hard to ignore. Forestry was still thought to be men’s work, so once animal husbandry was no longer an alternative, women began to cast about for other work. They often began by child-minding for neighbours or by working a few hours as a trained home help. As the public sector expanded rapidly, by the 1970s rural areas presented an entirely new labour market, above all in the care of the elderly and primary health services.34 Rural child-care was long organized as child-minding in the home, either by private or local authority child-minders, and kindergartens were not established until much later. Work in the primary and elderly care sectors was often part-time, with the possibility of adapting working hours to the agricultural seasons. Women brought in wages that were generally high compared to agricultural incomes–and they could still help during the peaks of the growing season.

For farming women, the time-saving effect of mechanized domestic appliances has been much debated. At the same time as women were increasingly relied upon around the farm, rising expectations of hygiene and a well-run home suggest that much of their housework had to be shifted to the evenings and weekends. The aestheticization of the home, the housewifely role, and the steady flow of new appliances and gadgets merely increased expectations of how a house should be run.35

Stronger farming organizations

From the middle of the 1950s, neighbourhood co-operation began to tail away. The accepted idea was now that each farm, if sufficiently efficient, should buy the machinery and implements needed for arable and livestock farming, with the servicing of these increasingly advanced machines left to specialized firms. Farms that could not finance the purchase and maintenance of machinery were too small and unprofitable to fit the agricultural policy ideal, and were thus slated for closure. Many farms were shut down–but not all. Here and there, small-holdings were run in combination with waged work. This permitted some neighbourhood co-operation to continue in villages where several farmers chose to continue small-scale farming, but it was against a background of exhortations from agricultural experts, banks, and advertisements to invest in new agricultural machinery, to modernize, and to increase production of a smaller number of products.

In his deliberations, the rational farmer of course considered costs. The price of machinery and tools did not rise as fast as wages. With versatile and efficient equipment, most of the work on a family farm could be undertaken by the family itself. Equally, it was away of avoiding the inconvenience of machinery associations – of having to wait politely for one’s turn despite imminent rain, with hay to be brought in or grain to be threshed. During the 1960s, job rotation and other forms of neighbourhood co-operation diminished while the number of people employed in agriculture continued to drop. While capital costs as a proportion of all costs in Swedish agriculture grew from some 25 per cent of the total cost at the start of the 1950s to approximately 30 per cent in the early 1970s, labour costs dropped from 60 per cent to under 50 per cent.

Instead, the farmers’ organizations’ movement became even more important. One of the cornerstones of the Swedish Model was the representation of various special interest groups on government inquiries and negotiation committees. Farmers were one such interest group, and agricultural policy was a key factor in modernization. Since agricultural products were priced at the negotiating table and not by the market, the leading agricultural organizations became a force in politics. The amalgamation in the autumn of 1970 of two associations –Sveriges Lantbruksförbund (Sweden’s Agricultural Association) and the RLF–to make the LRF gave Sweden’s farmers an even louder voice. Through LRF’s efforts in the media, the country’s farmers’ demands for higher prices for agricultural products met with growing approval from the general public. Price rises would compensate the farmers for rising input costs and–as set down by agricultural policy–would bring them up to the same level of income as comparable groups; a controversial issue that required an extensive government inquiry, with experts continuously collecting, analysing, and interpreting information from farms, shops, contractors, and the like. Despite all the effort, the parties rarely agreed on where farmers’ incomes stood relative to ‘comparable groups’.

As well as acting as a strong party in negotiations with the state and consumer organizations, the LRF offered a comprehensive service to individual farmers in matters such as book-keeping, law, taxes, machinery purchases, accident and health risks, banking, and insurance. It had its own dairies, slaughter-houses, wholesalers, and contractors, and it backed the local farming associations in matters of marketing, information, accounting, company law, data analysis, energy, veterinary medicine, and, not least, planning for the future.

It was in this central organization, with its constellation of co-operative associations, regional societies, and local divisions, that farmers were expected to put their faith during the high industrial period between the 1930s and the 1980s, when large-scale industry’s rational organization was the model for all forms of economic activity. Levels of income varied, but the 1970s seem to have been the post-war decade when agricultural incomes were at their highest. During this decade a younger generation took over the farms, and modernization proceeded apace with extensive investments in buildings and machines. It was also the time where the LRF enjoyed the greatest support amongst the country’s farmers and the public, and when neighbourhood co-operation was at its weakest. The situation would shift once again to become far more problematical in the next decade, when support for farming and rural areas diminished, and neighbourhood co-operation once more came to life, albeit in a slightly new form.

Several areas that had traditionally been under direct political control were deregulated in the 1980s, in particular parts of the social and economic system, while the environment was increasingly viewed as a central political issue. Those who put their faith in free market forces looked askance at the expense and inefficiency of heavily regulated agriculture, and the complexities of agricultural policy. Further, the policies so favourable to agriculture in the 1970s had turned out to result in problematic surpluses. In 1982 the government decided to embark on a general review of food policy. The choice of name– ‘the 1983 food committee’–was intended to mark the conscious transition from agricultural policy to food policy. The committee’s work was continued in 1988 in the ‘food policy working group’. The Social Democratic government announced to both committees that it now wanted to tear down the barriers to development that the regulations had put in place. When the regulations were gone, agriculture could develop along more commercial lines.36 The 1980s became a decade of agricultural policy debate that was almost as heated as that in the 1960s, and several official programmes were introduced to reduce the surplus. At the end of the 1980s the LRF also began to position itself in favour of the deregulation of agriculture, and in 1991 Sweden’s Parliament became one of the first in Europe to adopt a new agricultural policy. Food production was to be treated like any other form of production. Deregulation had not progressed far when Sweden applied for membership of the European Union.37

Supra-national agricultural policy

A decade into the new millennium, and it seems obvious that the heyday of the Swedish welfare state is over. Even if the Swedish welfare state and the Swedish Model survive in outline, the relationship between citizen and state has changed beyond recognition. The broad, corporative solutions are quietly crumbling, matched by the gradual relocation of industry and the production of goods overseas. When discussion of the new post-war agricultural policy was at its most intense, a number of critical voices warned that industry might well prove a bent reed, and that it was ill-advised to lure farmers from agriculture to industry. It was impossible to predict at the time how enormous the growth of the service sector would be, neither how the digital revolution and increasing globalization would fashion a new agricultural reality, bringing in its wake the deregulation and dismantling of much of Sweden’s national agricultural bureaucracy. Where, seen in a social perspective, the purpose of agriculture was once to produce cheap food and increase productivity while not tipping over into overproduction, this has now become both the curse and the promise of agriculture in terms of sustainability. In many important respects, agriculture has taken a step into a postmodern and post-industrial era, while production continues to obey the laws of biology and photosynthesis.

When Sweden joined the European Union in 1995, its national agricultural policy effectively ceased to exist. Even if the aims of the EU’s policies broadly coincided with Sweden’s previous goals, the direct relationship between state and agriculture has been broken in several crucial respects. While Swedish farmers previously determined their fate in direct negotiations with the state over prices, quotas, and conditions, market forces now largely hold good in the internal market. This has brought greater insecurity, but also opportunities for greater creativity and freedom. Some agricultural policy is still determined by individual member countries, however. A central pillar of the EU’s policy is acreage subsidies, and in the EU’s simplified Common Agricultural Policy of 2005, Sweden decoupled them from agricultural production, instituting instead farm subsidies allocated by the acreage of farmland in existence on a specific date, regardless of whether the ground was worked or not–mowing was sufficient to qualify.38 This affected Swedish agriculture in several respects. Farming businesses that had not previously been included in the register now were, and while the proportion of leased land had increased for a number of years, this trend has now been broken, which can in part be explained by the transition to farm subsidies rather than crop subsidies. Landowners take most of the responsibility for farming operations and the farm subsidy, even if in practice the actual work of cultivation is hired out. It seems probable that farm subsidies have encouraged the rising sale prices of both leases and freehold farmland.

The social questions that for the entire post-war period prompted so many political disputes have largely vanished from the discussion, and when they are mentioned it is usually in the wider rural context. There are no battles over the continued existence of small-holding, or the ideal size of a farm. The land-acquisition law was liberalized at the start of the 1990s, and even though regulations remain in place that give the regional agricultural boards and their equivalents responsibility for farm rationalization, it is in principle free for anyone, regardless of background or purpose, to acquire agricultural land. That said, there are still relatively few sales to those outside the immediate family circle.39 The almost manic attempts to create idealized agricultural businesses in the post-war period, and the agricultural experts’ determination to define family farms, large-scale farming, and small-holding, have been completely overtaken by a multitude of business constellations and individual solutions.

Even if the existing policy is not as misogynist as that of the 1930s and 1940s, an underlying sense of what is men’s work and what is women’s endures to this day. Supposedly gender-neutral texts blithely assume that all farmers are men as soon as they turned to industrial-scale agriculture, while a range of measures to increase the number of small businesses are directed specifically at women, preferably in small-scale food processing or tourism. With the current formulation of EU statistics, where only one person can stand as the owner of an enterprise even if there are several joint-owners, a certain amount of female enterprise is necessarily glossed over, while in other respects it is now better reported thanks to the improved formulations that capture the alternative sources of income generated by the farm. When LRF looked at agricultural companies to check the actual proportion of women in leadership positions, it found that a third of them were run by women, while the official Swedish statistics gave a figure of 16 per cent. 40

The direction taken by Swedish agricultural policy within the EU’s framework is to focus on issues such as cultural landscape, biodiversity, nitrogen and phosphorus emissions, animal welfare, ecological production, and the manufacture of renewable energy. The cultural landscape and biodiversity are examples of issues that have existed since the 1960s, running parallel to the mainstream debate. In those days there was much talk of the landscape as a kind of benefit produced by agriculture alongside the actual food, and it was only towards the end of the century that this became a central issue, in which the biological and historical worth of the landscape came to the fore. The landscape has become a product that farms can be paid to produce–an ecosystem service, hedged about by subsidies and its very own bureaucracy. The political rhetoric of the twenty-first century attributes to the landscape the power to bring people peace of mind and joy, and to satisfy their need to experience beauty. Often the simple, enduring worth of the landscape is set against the more complicated urban environment. In Sweden, grazing grounds have a central place in the national consciousness. In their mix of spring flowers, ancient oaks, birches, hazel thickets, and songbirds many Swedes glimpse paradise, while the EU’s agricultural bureaucrats scratch their heads and wonder whether they should really be subsidizing brushwood and forest.41

Small-scale and large-scale farming in a new age

At the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, Sweden has some 73,000 agricultural units of over 2 ha, and the country as a whole has a cultivated area of 2.6 million ha. Businesses with over 100 ha are on the increase, while the rest are decreasing. Yet only a quarter of all farms are reckoned full-time enterprises. The term småbruk, so long an indication of the size of a property, as in ‘small-holding’, has now taken on a new official meaning as a ‘small-scale farm’, indicating the total number of hours worked (less than 400 per annum). The 25,000 small-scale farms have much the same distribution countrywide as in previous decades, and dominate in the north and west of the country. The reason so many districts can still be reasonably described as living landscapes is the infrastructure of small-scale farms that have now survived sixty-plus years of agricultural policy. In statistical accounts of the number of people involved in agriculture, the difference is considerable depending on whether the starting-point is socio-cultural or strictly economic. In the official ‘permanent’ and ‘temporarily employed’ categories, there are 174,000 individuals; in other words, a relatively large number of people are in one way or another still involved in agricultural work. Seen in terms of employment, agriculture accounts for approximately 72,000 person–years (the amount of work done by one person in year), of which family labour contributes 54,000 person–years. It has been found that some 87 per cent of all children between 7 and 18 who live on a farm join in the work, primarily animal husbandry.42

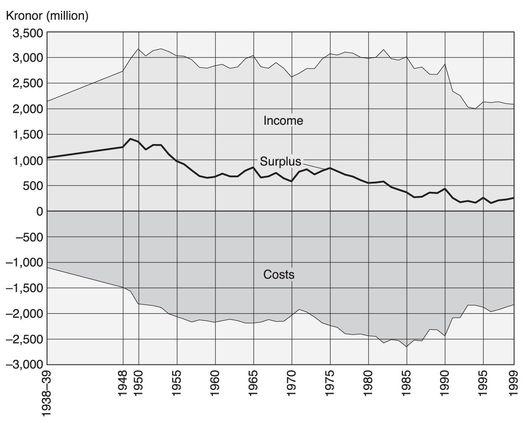

Figure 6.4 Total income from agriculture against costs, 1938–99 (in 1950 terms). Starting in the early 1950s the surplus slowly declined, but then stabilized and showed a slight improvement at the start of the 1970s and again at the end of the 1980s. Source: Flygare & Isacson 2003, 170, 378.

Swedish farm acreages have increased to an average of 36 ha with a mix of freehold and leased land, and are now finally of an order that in the 1930s was thought an ‘ideal farm’ needed to support two families, although the trend is now in the other direction, and few farmers support themselves by their farms alone, for a third of all their income is derived from other sources.

The family still stands for most farm labour, and it is the family that owns both the land and the farming business; yet the family is also involved in any number of enterprises and hybrid operations based on land, animals, buildings, and machinery. A relatively modest-sized farm can, with carefully chosen leases, evolve into a substantial farming unit spread over a large area, its farm machinery owned jointly with other farmers in a special company, some of which may be intended for outside contract work; on the home farm there might be some kind of tourist trade or farm shop; while perhaps there might be a chance of contracting to cultivate the arable fields of the neighbouring part-time farm, whose owners combine raising beef cattle with jobs in town or running their own business in a skilled trade. Several very large agricultural units have been created by a number of farmers pooling their land and forming a management company, in which the various leases and cultivation contracts on other farms contribute to increasing the acreage even more. The benefits include the opportunities to retain employees and to maintain a good range of farm machinery. Even in livestock farming there are examples of similar initiatives, with the construction of joint barns. The legal forms vary from the Swedish equivalent of the joint stock company to other, simpler, forms. Between 1988 and 1999, the acreage held by joint stock companies rose from 98,000 ha to 334,000 ha, or 12 per cent of the total. That said, the system of leases plays a more important role for the size of the final units, which largely revolve around leased land. The use of various forms of corporation means that ‘farms’ as distinct units in one sense cease to exist. Even to the practised eye, it is impossible to look at Swedish farms today and instantly determine their economic potential and productivity. What at first glance may appear a half-heartedly developed farm may well prove to be the principal farm in a large agribusiness. That said, interview studies have shown that the home farm–the farmer’s own farm, the constant in all the various constellations–is emotionally important, and is the one thing many want to be certain of passing on at a change of generations.43

Even if there was never any absolute correlation between the number of farms and the number of farmers, there was always an illusion of one farming family per farm. Today’s situation would have been the worst nightmare of one of the 1940s’ rational agricultural planners or statisticians. It is still the case that those running the farms have usually taken over from parents or close relatives .44 The cost of land in the best arable areas has soared in recent years, possibly because of farm subsidies, which has a knock-on effect on the costs of leasing land. The group that the 1940s’ land-acquisition law was meant to fend off–individuals of independent means–now has almost full access to the property market in farmland and forestry. A liberal policy on land acquisitions has made it possible for people other than farmers to buy a farm. The choice that they then face is between keeping the arable land and leasing it out, or parcelling most of it off for sale, while keeping the forestry and a small amount of land, often to keep riding horses on. It is this that drives the creation of these new mixed businesses. While there is a trend towards ever-larger farming units, at the other end of the scale, farms that were previously considered ‘complete units’ are being divided up, producing new, small-scale farms and forestry property.

This is particularly true of the relatively cohesive farming areas where the rural population was quite large. The picture is very different in the area that runs from the western province of Dalsland up to Norrbotten. Farms here had always been few in number–remote farmsteads and a great deal of late settlement–so the farm closures of the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries are appreciable in their effects on both the landscape and the community.

Combined contract farming

Swedish agriculture today is best described as combination farming–not to be confused with mixed farming, which denotes a mix of arable and livestock farming. Few businesses can survive on classic food production, and instead they branch out into a range of ancillary operations that are particularly crucial to the very large farms. The most important is the contracting business, followed by tourism, renting out rooms, and the production of renewable energy. The reason the larger farms tend to concentrate on contracting is because they already own the heavy machinery that is only used seasonally and their existing employees need to be occupied full time. Forestry still plays a large role, but the current trend is for forest farms to reduce the amount of arable land they hold. The pressure for farm-owned forest to be incorporated into the production of renewable energy is increasing, and because such crops are also important in arable farming, there are indications that the gap between the two kinds of farming is being bridged.