2 A brief anatomy of choirs c .1470–1770

Josquin des Prez, Tallis , Victoria , Monteverdi , Charpentier , Bach – the great choral composers of the past may be presumed to have understood the inner workings of their choirs comprehensively well; most had received a choirboy’s education and virtually all spent a lifetime amongst their chosen singers. But to what extent do we share their understanding? Was Dufay ’s body of singers little different from those that Handel knew some 300 years later? Has “the choir” somehow managed to remain essentially one and the same thing through the ages to our own time? Though much transcribed, discussed and performed, music written for choirs in earlier centuries generally reaches us through a filter of more recent choral expectations, with unfamiliar features disregarded, overlooked, or misconstrued. Thus, while close attention is routinely paid to specific works and their composers, and to compositional genres and choral institutions, the focus here will instead be on the very nature of those diverse musical bodies we call choirs.

Since for much of the period under consideration choral performance was nurtured almost single-handedly by the Church, it will suffice to define a “choir” provisionally as “An organized body of singers performing or leading in the musical parts of a church service.” 1 This has the merit of making no attempt to prescribe how such a body is musically organized (whether for unison singing, or for music requiring just three solo voices or a multiplicity of voices intermixed with instruments), and it therefore encourages us not to concentrate unduly on familiar aspects of “choral” performance as we now understand it.

Improvised polyphony

The bedrock of the Church’s music making was plainchant, much of it sung from memory, 2 and the evolutionary link between solo or unison chant and later composed choral polyphony lies in the hidden (and little explored) world of extempore chant-based singing. This could take many forms (variously named), from simple note-against-note affairs to the intricate counterpoint of highly skilled singers; 3 by the mid fifteenth century English clerical singers were practicing at least three such techniques – faburden , descant and “counter.” 4 Different techniques tended to attach themselves to different portions of the liturgy: at the church of Our Lady in Antwerp (1506), the Alleluia and Sequence were to be performed in discant , the Communion with contrapuncte , and the Introit “without singing upon the book .” 5 Though not required in this instance, the technique of singing “upon the book” (super librum ) is perhaps particularly relevant to the story of the choir. Its underlying principle, according to Tinctoris in 1477, was that

when two, three, four or more people sing together upon the book, they are not subject to one another. In fact, it is enough for each of them to accord with the tenor in regard to the rule and ordering of consonances . 6

Was something of this sort what Thomas Morley (1597) had in mind?

As for singing uppon a plainsong, it hath byn in times past in England (as every man knoweth) and is at this day in other places, the greatest part of the usuall musicke which in any churches is sung. Which indeed causeth me to marvel how men acquainted with musicke, can delight to heare such confusion as of force must bee amongste so many singing extempore . 7

We may well share Morley ’s scepticism (and a Neapolitan writer likened the results to “music made by cicadas”), 8 yet Banchieri (1614) assures us that “In Rome in the Chapel of Our Lord, in the Santa Casa di Loreto and in countless other chapels” such extempore singing (contrapunto alla mente ) was “most tasteful” to hear:

It is a general principle that, with as many as a hundred different voices singing in consonance over a bass, all are in harmony, and those wicked 5ths, octaves, oddities and clashes are all graces which create the true effect of improvised counterpoint . . . 9

Although small numbers of skilled singers are likely to have produced more consistently “correct” results, this particular method of improvising over chant seems to have been capable of accommodating more than a mere handful of solo voices: 10 in mid eighteenth-century France there were still churches where “almost everything is sung according to chant sur le livre [upon the book],” perhaps by “thirty or so musicians . . . all at the same time; some according to the rules and others completely at random.” 11

Extempore traditions of one sort or another were clearly a major part of choral practice far and wide. 12 From St. Mark’s, Venice , at the end of Monteverdi ’s tenure as maestro di cappella , it was reported that “ordinarily they sing from the large book, and in the cantus firmi they improvise counterpoint .” 13 And, as a Dutch traveler observed at the basilica well over a century earlier in 1525, the elaborate liturgy of a major feast day demanded that the choir’s duties were variously distributed amongst the singers present:

Outside the sanctuary there is a beautiful round large high stuel [tribune/pulpit], decoratively hung with red velvet cloth of gold, where the discanters stand and sing. And those who psalmodize sit on both sides of the choir, on the one side plainsong, on the other side contrapunt or fabridon (whichever name you prefer); these three [groups] each await their time to sing, up to the end of the Mass . . . 14

This serves to alert us to two recurrent difficulties in establishing the size and nature of earlier choirs. Just as the institutional strength of a choir will not reflect any extra singers brought in on a temporary or occasional basis, so too does it fail to take account of absences, rota systems, the function or importance of an event, and – not least – such divisions of labor within a service as have just been noted. As for depictions and documentary tallies of singers, it is exceptional to be certain whether composed or improvised polyphony or even simple chant is being sung.

These questions arise with a source that may otherwise appear to be a key guide to the performance of composed choral polyphony at the Burgundian court in the time of Busnoys. New ordinances for the court chapel drawn up in 1469 specify that

for chant du livre there shall be at least six high voices, three tenors, three basses-contre and two moiens [“means”] without including the four chaplains for High Mass or the sommeliers who, whenever they are not occupied at the altar or in some other reasonable way, will be obliged to serve with the above-mentioned. 15

First, by proceeding to ensure “that the service be always provided with two tenors and two contres ,” 16 the ordinances remind us that this institutional complement (or “pool”) of singers will not have been expected on all occasions. Second, “chant du livre ” may well be no more than a synonym for “chant sur le livre ,” 17 an improvisatory technique both suited to fluid numbers of singers and requiring a good spread of voice ranges – a technique, moreover, used “when they sing each day in the chapels of princes” and notably by “those from across the Alps, especially the French.” 18

Composed polyphony

With the music of Dufay we are on slightly firmer ground. In his lengthy will drawn up at Cambrai in 1474, the composer requests that on his deathbed – “time permitting” – two pieces of music be heard; first a chant hymn sung softly (submissa voce ) 19 by eight Cathedral men, then his own Ave regina coelorum 20 sung by the (four to six) “altar boys, together with their master and two companions.” 21 Instead, as time did not permit, both items were apparently given in the Cathedral the day after his death, together with Dufay ’s own (lost) Requiem , 22 for which he had specified “12 of the more competent vicars, both great and lesser” (about half of the total). 23 Dufay ’s will also provides for a mass of his to be sung on a separate occasion by “the master of the boys and several of the more competent members of the choir,” the allocated funds allowing for exactly nine singers. 24 It is worth noting that the precise location for this, and almost certainly for the Requiem , was not the choir of the Cathedral but one of its chapels. 25 Indeed, the (private) chapel, whether part of a church or an independent structure, arguably counted as “the most important place for music-making in the late Middle Ages,” perhaps explaining why the chaplains of a princely chapel, whose duties were many and varied, frequently outnumbered the singing body of a great cathedral. 26

Substantially larger vocal forces than those specified by Dufay were certainly heard from time to time, but only in exceptional circumstances. In 1475, for example, at a Sforza wedding mass in Pesaro two capelle sang “now one, now the other, and there were about 16 singers per capella .” 27 A century later Lassus annotated the alto, tenor, and bass parts of a twelve-voice mass by Brumel with the names of thirty-three men – including himself as “Cantor” 28 – and for the Medicis’ extravagant 1589 intermedi a madrigal a 30 was sung in seven choirs by sixty voices with opulent instrumental support. 29 By contrast, the musical establishment at Florence Cathedral in 1478 comprised just four boys, their master and four other adult singers. 30 Ensembles of this nature were evidently something of a norm:

- Venetian ambassadors traveling through the Tyrol in 1492 enjoyed “the singing of five boys and three masters”; 31

- as “song master” at St. Donatian’s in Bruges (1499–1500) Obrecht was “obliged to bring with him to each Salve, besides his children [choirboys], four companion singers from the church, and those who sing best”; 32

- Jean de Saint Gille’s testament (1500) promises a pour-boire to six named singers and “several” of the boys at Rouen, who were “to sing the Mass for the Departed that I have composed.” 33

Figure 2.1 Arnolt Schlick, Spiegel der Orgelmacher und Organisten (Speyer, 1511); woodcut – straight cornett, organ and singers (three boys and two men)

Some of these boys may have been the equivalents of today’s eleven- or twelve-year-olds, but the more complex polyphony of the period reminds us that boys’ voices were commonly not changing until sixteen or even later. 34 Northern Europe led the way in training young singers, and in France (1517–18)

there is not a cathedral or major church where they do not have polyphony constantly and more than one mass sung every day; each one is supplied with six or eight little boy clerics who learn singing and serve in the choir, tonsured like little monks and receiving food and clothing. 35

Institutionally these choirboys were often independent of their adult counterparts – Cambrai’s boys served as acolytes and sang at their own lectern near the high altar 36 – and the collaboration of men and boys in elaborate composed polyphony marked a significant development in the fifteenth century. 37

Interest in this new wider choral range may in turn have driven the cultivation of another type of high voice: that of the adult falsettist (better known as today’s “countertenor” ). To Pietro Aaron (1516) a cantus part was now one to be sung by either a boy’s voice or a man’s “feigned” voice (“cum puerili voce, vel ficta ”). 38 In the absence of earlier hard evidence, 39 we may conjecture that the increasing value of keeping boys singing for as long as possible led to an adolescent “falsetto ” technique 40 which some then retained and developed into adulthood as falsettist sopranos. (In Germany it may have been quite usual for boys to move from soprano to alto before settling into a lower range.) 41 Revealingly, non-child sopranos, many of them described as youths, were often taken on only for “as long as their voices shall last” (and sometimes “placed in the house of the choirboys”), 42 or given a one-year contract specifically “in case . . . the singer should lose his voice.” 43 In one instance, a soprano who signed such a contract in Florence shortly before Christmas 1481 received a “farewell gift” just eleven days later. 44

The need for dependable high voices could, of course, be satisfied in another way – by castrati , who as a musical force seem to have emerged in Spain only a little later. At Burgos Cathedral a castrated boy “who has a good voice” was noted as early as 1506, 45 and by the 1560s Spanish castrati could be found in Italy at the court of Ferrara, in the papal chapel, and at St. Mark’s, Venice . 46 (Homegrown Italian castrati eventually displaced these Spaniards in Italy.) 47

Ranges, clefs, and vocal scoring

Only slowly did the “voice” labels of polyphonic music (cantus , contratenor and so on) begin to attach themselves not just to parts but to distinct vocal ranges and thence to particular categories of singer. In practice, the “key” to vocal scoring – widely assumed today to have been a distinctly casual affair – was the humble clef, 48 which mapped out an individual core range (of up to eleven notes) and fixed its relationship to others; see Example 2.1 . A composer, having chosen a mode and vocal scoring, worked from a corresponding set of clefs, always aware that

you must not suffer any part to goe without the compasse of his rules [=lines], except one note at the most above or below, without it be upon an extremity for the ditties [=words’] sake or in notes taken for Diapasons in the base . (Morley, 1597) 49

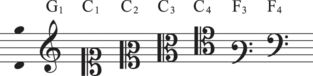

Example 2.1 The implied range of a five-line stave and the most commonly used clefs

The clef configuration C1 C3 C4 F4 , for example, can thus identify and broadly define the four principal vocal ranges of later Renaissance music, cantus , altus , tenor , and bassus (CATB ). Confusingly enough, however, these very same voices could also be expressed by a different set of clefs and consequently at different written pitch levels. 50 The motet Absalon, fili mi (variously attributed to Josquin and Pierre de la Rue ) – an extreme example perhaps – survives in “contradictory” sources, the earliest one lying exceptionally low (C3 C4 F4 F5 ), others a surprising 9th higher (G1 G2 C2 C3 ). 51 In fact, only the clefs and key signatures have changed; the notes themselves occupy identical positions on each stave, divergent pitch names being (as Cerone puts it in 1613) “of no concern to the singer, who is concerned only to sound his notes correctly, observing the intervals of tones and semitones.” 52 Musical notation, in other words, deals in relative pitches – and is frustratingly reticent about their absolute sounding pitch.

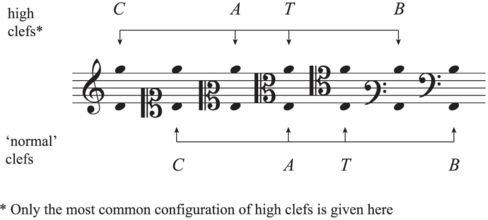

What may appear to be a bewildering array of clef configurations employed by Renaissance composers is perhaps best viewed as a series of purely notational permutations of a limited number of reasonably standard vocal ranges. By the end of the sixteenth century most choral music was in practice notated either in “high” clefs (later dubbed chiavette ) or in a set that had become increasingly more “normal”; see Example 2.2 . As it happens, two-thirds of Palestrina ’s considerable output is notated in high clefs, giving us the misleading impression that it was intended to sound distinctly higher than the remainder (in “normal” clefs), simply because that is how it looks to us – a view that would surely have amused Palestrina ’s singers, just as theirs may baffle us.

Example 2.2a Original notation

Example 2.2b As generally transcribed today

Apparent discrepancies of this sort naturally became real issues whenever instruments were involved, and consequently the art of transposition was viewed by Zarlino (1558) as “useful and highly necessary both to every skilled organist involved with choral performance and similarly to other instrumentalists .” 53 Thus, while all high-clef items in a book of Palestrina motets reissued in 1608 are found transposed downwards in its newly added organ part, 54 all 37 in a similar collection by G.P. Anerio (1613) bear instructions such as “alla quarta bassa ” (“to the 4th below”). 55 The necessary procedures are set out by Praetorius in 1619 in the clearest possible terms:

Every vocal piece in high clefs, i.e. where the bass is written in C4 or C3 , or F3 , must be transposed when it is put into tablature or score for players of the organ, lute and all other foundation instruments, as follows: if it has a flat, down a 4th . . ., but if it has no flat, down a 5th . . . 56

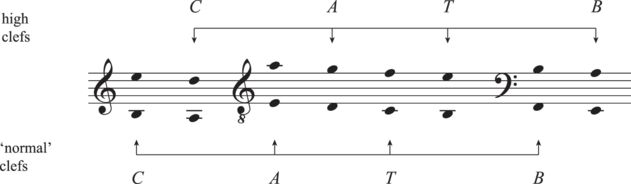

Example 2.3 compares core ranges of “normal” and transposed high clefs (down a 4th). Primary transposition of this sort – almost always obligatory – is not to be confused with any smaller secondary adjustment designed to suit specific circumstances: to deal with differing instrumental pitch standards and/or to accommodate particular voices. In both cases the abiding principle was that instruments should defer to voices, rather than the opposite. Hence,

organists are always (or at least usually) compelled to play lower than the written key in order to accommodate the singers. This is what is done at St. Mark’s in Venice . . . 57

Example 2.3 Relative ranges with high clefs transposed down a 4th

High- (and low-)clef notation, considered the worst “among the many abuses which are traditionally current in music,” 58 eventually died out, but as late as 1657 Schütz could still publish a work with the vocal parts in one key (using high clefs) and the organ in another (a 4th lower). 59

Voice types

To compound the difficulties of understanding these notational conventions, known pitch standards could vary enormously, anywhere from roughly a tone below today’s a′ = 440Hz to a tone above (as, respectively, with many late seventeenth-century French woodwind instruments and Buxtehude’s organs in Lübeck) 60 – and from the fifteenth century and earlier there is virtually no reliable information. It is therefore critical to recognize that cantus , altus , tenor , and bassus are not necessarily direct equivalents of today’s SATB classifications. A particular cause of misunderstanding is the view that “Falsetto singing has been the most common source of alto voices in all-male choirs throughout the history of Western music.” 61 Wherever they are known to have been employed in the sixteenth century, falsetto (and castrato ) voices were associated not with alto parts but only with soprano parts – which in turn lie significantly lower than those of later periods. 62 As for the (non-falsetto) alto voice, it corresponds to our (high) tenor and formed a pair with a slightly lower “middling” tenor, generally considered the “ordinary” voice. 63 Palestrina ’s voices, for example, are distributed as shown in Table 2.1 .

* Neither “treble” nor “countertenor” adequately evokes the part’s intermediate “mezzo soprano” range.

English vocal scoring, especially in the earlier part of the sixteenth century, differs significantly from this in often employing not four but five basic ranges ( Table 2.2 ). The lower three of these voices correspond to those of Palestrina and are “changed voices” covering the two octaves or so above a bass’s lowest note, but where Palestrina has just a cantus above them, English music often has two distinct upper voices, “treble” and “mean.” 64 Not only is there a total absence of documentary evidence for falsetto singing in sixteenth-century England (unlike Italy , for example), but English organ pitch – no higher than a semitone or so above today’s a′ = 440Hz 65 – all but rules out today’s countertenor for contratenor parts. 66 Moreover, though the “mean” part may appear well suited to today’s countertenor, 67 the associated voice was “higher than mens voyces.” 68 It is only ever documented as belonging to boys: the Earl of Northumberland’s “Childeryn of the chapell,” for example, comprised “ij Tribills and iij Meanys” (c .1505), 69 while Salisbury Cathedral specified “eight choristers having good commendable voyces for trebles and meanes” (1580). 70

| Part | Singer |

|---|---|

| triplex /treble | boy (high) |

| medius /mean | boy (low) |

| contratenor /countertenor | 1st tenor |

| tenor /tenor | 2nd tenor/baritone |

| bassus /bass | bass |

Instruments

By the mid 1400s the organ had become well established as a church instrument, but only later did other instruments slowly gain admission on any regular basis. While scattered references to “trumpets” and other wind instruments often relate to the Mass (sometimes specifically to the Elevation), there is little to suggest their direct involvement with liturgical singing on any frequent or systematic basis before 1500. 71 But in that very year we read of masses being sung (at John the Steadfast’s wedding in Torgau) “with the help of the organ, three trombones and a cornett, [and] likewise four crumhorns with the positif .” 72 Did these instrumental groups merely play, for example, at the Gradual and Ite missa est (as the organ might otherwise have done, and as trombones evidently did at Innsbruck three years later), 73 or were they used to bolster the vocal forces in polyphonic settings of the Kyrie, Gloria, and so on? The same questions are raised by recurrent reports (1501–6) citing Augustein Schubinger, an Imperial cornettist in the retinue of Philip the Fair, playing at mass . 74 The matter is at least partly settled, however, by a woodcut of Maximilian I’s Hofkapelle , showing a trombonist and a cornettist (almost certainly Schubinger) reading from the same choirbook as a dozen or more singers. England ’s court singers perhaps first encountered this type of mixed ensemble a little later, at the Field of the Cloth of Gold (1520), when their French counterparts were joined in a Credo by trombones and “fiffres .” 75 For Erasmus (1519) these instrumental intruders contributed to the objectionably “elaborate and theatrical” nature of church music, 76 whereas Vasari’s reaction to hearing “a multitude of trombones, cornetts and voices” perform a Gloria at a Florentine ceremony in 1535 was to proclaim that “the earth seemed gladdened.” 77

Instrumental participation of this kind was clearly intended to enhance the pomp and ceremony of grand occasions, but there could also be a more general practical purpose:

Cornetts and trombones have been invented and introduced into musical ensembles more from the need for soprano and basses, or rather I should say to add body and sheer noise . . . than for any good or desirable effect that they may create . (V. Galilei, 1581) 78

singers with sufficiently deep bass voices are extremely rare, which is why the Basson, sackbut and serpent are used, in the same way that the cornett is employed to stand in for treble voices, which are usually not good. (Mersenne, 1636) 79

At the reopening of England ’s Chapel Royal in 1660, cornetts were accordingly drafted in to help “supply the superiour Parts” of the music, “there being not one Lad, for all that time, capable of Singing his Part readily,” 80 while a full century later the bassoon was proving “in great Request in many Country Churches . . . as most of the Bass Notes may be played on it, in the Octave below the Bass Voices.” 81 As Roger North put it in 1676, “nothing can so well reconcile the upper parts in a Quire, as the cornet (being well sounded) doth.” 82 With their distinctly vocal colour, range and flexibility (of tuning and volume), cornetts and trombones integrated themselves into vocal choirs to the extent that in the late 1580s one singer at a Roman church was able on occasion to send a trombonist to deputize for him, 83 while elsewhere the permanent membership of a courtly chapel included “two basses, one is a trombone .” 84

Stringed instruments were slower to find a place in church music making – and slower in England than elsewhere: in 1636 it was noted that “in our Chyrch-solemnities onely the Winde-instruments (whose Notes ar constant) bee in use”. 85 (The viol consorts associated with English verse anthems of the period belong to the world of domestic performance and are undocumented in church sources.) 86 In Rome, however, the upstart violin had clearly made its entry by 1595, when a maestro di cappella might be expected to present “two Vespers and a Mass for three choirs, with voices (some from the papal chapel) combined with instruments (namely cornetts, trombones, violins and lutes).” 87 Earlier still in Madrid, Marguerite of Valois had attended a mass “after the Spanish fashion, with music, violons , and cornetts.” 88

New directions

The gradual acceptance of instruments besides the organ led church music in new directions. While double-choir writing of the mid sixteenth century had in essence been entirely vocal (although instruments might double or even replace voices), the polychoral works of Giovanni Gabrieli and others commonly included not only a basso continuo but additional parts specifically for instruments. The various “choirs” – perhaps separated vertically as well as horizontally – might thus be either

- purely vocal (some for single voices, others for multiple voices with or without instrumental doubling),

- purely instrumental (whether or not for a single family of instruments), or

- for a particular combination of voices and instruments.

No longer was the compass of each choir restricted to that of human voices: 89 a tenor might supply the top line of a “low” choir with trombones beneath, or the lowest line of a “high” choir headed by a cornett or violin. And in many cases the number of choirs could be varied simply by omitting or duplicating certain of them. Thus Viadana’s Salmi a quattro chori (1612)

may also be sung by just two choirs, namely Choirs I and II. However, if one wishes to put on a beautiful display with 4 to 8 choirs as the whole world likes to do nowadays, the intended effect will be achieved by doubling Choirs II, III and IV, without any danger of making an error; for everything depends on Choir I a 5 being sung well. 90

While the four-part Choir II functions here as “the capella , the very core and foundation of a good musical ensemble” (for which “there should not be fewer than sixteen singers”), the choir on which “everything depends” – Viadana’s “favored” first choir – consists of just one singer per part:

Choir I a 5 stands in the main organ gallery and is the coro favorito ; it is sung and recited by five good singers. 91

In practice, ripieno or capella singers rarely needed to be quite as numerous as Viadana suggests: Usper (1627) speaks of “doubled and tripled voices together with proportionate instruments on each part, as is done in the most famous city of Venice.” 92

This new Italian polychoral manner was soon adopted by German composers, notably by Schütz, who explains in his Psalmen Davids (1619) that

the second choir is used as a capella and is therefore strong [in numbers], while the first choir, which is the coro favorito , is by contrast slender and comprises only four singers . 93

And in France the same underlying principles produced the French grand motet :

the grand choeur , which is a 5, is always filled with a number of voices; in the petits choeurs the voices are one to a part. 94

(For Du Mont, sections marked “omnes ” are “when there are two people on the same part.”) 95 This distinction between an elite one-to-a-part vocal choir and a larger – though not necessarily large – body of singers is fundamental to a proper understanding of much “concerted” vocal music, whether polychoral or otherwise. 96 The chief protagonists of most seventeenth-century concerted music were these select one-to-a-part vocal ensembles (or “consorts,” as they are now often called); in Praetorius ’s words, such “choirs” of concertato voices constituted “the foundation of the whole concerto .” 97 Moreover, where there is capella writing, it is generally subsidiary and frequently optional; 98 even for a grand motet “it would suffice to have five solo voices.” 99

One-to-a-part choral singing was, of course, nothing new. A foundation at Chichester Cathedral (c .1530) had provided for just four adult singers of polyphony , stipulating a combined vocal range for them of 15 or 16 notes. 100 In Venice in 1553, the Cappella Ducale’s seventeen members could form four separate choirs for employment outside St. Mark’s, 101 while at the basilica itself in 1564, in an intriguing anticipation of later practice, they sang psalms “divided into two choirs, namely, four singers in one choir and all the rest in the other.” 102

In keeping with his earlier small-scale “ecclesiastical concertos,” Viadana’s Lamentationes (1609) are designed for “just four good voices” (though without organ), but for different reasons. These highly charged texts called for the particular expressive capability of an ensemble of expert solo voices, 103 and at the papal chapel one-to-a-part singing by select singers is documented in this and other Holy Week music (including Miserere settings such as Allegri’s ). 104 Different conditions demanded different treatments, and the Responsoria from the same publication are expressly to be sung by four or five singers per part, but with the falsobordone verse taken by four solo singers. 105 Similar alternations of solo voices and “full” choir characterize Byrd ’s Great Service and are all but explicit in the red- and black-ink underlay of the Eton Choirbook (c .1500). 106 In many other repertoires – notably in most sixteenth-century masses – certain portions of text (Crucifixus, Benedictus etc.) may imply single voices, especially when set in a reduced number of parts. 107

Certain idioms lent themselves equally to single and multiple voices. In the largely homophonic writing in Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo (1600), variety was evidently also welcome:

When the choir’s music is in four parts, one can, if desired, double them and have now four singing and sometimes all together, provided the platform can accommodate eight. 108

Doubled voices, however, had at least one clear disadvantage:

adding coloraturae in a choir spoils the result, for when one part is assigned to be sung by several people, it is inevitable that the coloraturae will be completely different, and hence both the beauty and the nature of the sound are obscured. (Finck, 1556) 109

As a general rule, vocal writing containing wide ranges, extended runs, complex rhythms or chromatic intricacies is most likely to have been intended for single rather than multiple voices. Defining “da Capella ” in compositional terms, Walther (1732) explains:

if many voices and instruments are to do one and the same thing accurately together, the composition must also be designed so that this can happen properly. Accordingly one finds that good and experienced masters employ only whole-, half- and quarter-notes in an alla breve , but dispose them in sundry ways with such great artistry and skill . . . 110

From Monteverdi to Bach

Single- and multiple-voiced choirs continued to coexist and to complement each other, as did new- and old-style repertory (in stile concertato and stile antico ). Thus Monteverdi ’s famous 1610 publication opens not with the Vespers music but with a rigorously contrapuntal Missa da capella based on a motet already many decades old, 111 and a century later we find amongst Alessandro Scarlatti’s diverse church works a Messa breve a Palestrina . Even right at the end of our period, Charles Burney , in Florence, could hear vespers music “all in the old coral style of the sixteenth century,” 112 and, at Milan Cathedral , music from “about 150 years ago”:

the service they were to sing [was] printed on wood in four parts, separate, cantus–altus–tenor–bassus – out of which after the tone was given by the organist . . . they all sung, namely 1 boy, 3 castrati , 2 tenors and 2 basses, under the direction of the Maestro di Capella, without the organ. 113

In Germany , where the motets of Handl , Lassus, and their contemporaries formed the staple diet of Lutheran choirs well into the mid eighteenth century, a printed anthology of such works – Florilegium Portense (1603 and 1621) – may still have been in use in Leipzig as late as 1770. 114

While Monteverdi ’s 1610 Vespers gives not the slightest hint of requiring more singers than there are voice-parts (solo /tutti indications are entirely absent), the sober writing of the Mass is clearly suited to a reasonably “strong” capella of singers (with continuo, and therefore not a cappella in the sense of “without instruments,” a meaning which dates from the nineteenth century). Similarly the traditional Lutheran motet could invite “wherever possible . . . a very strong contingent of singers,” 115 in clear contrast to concerted music. “How many persons are actually needed for a well-appointed musical ensemble?” asks Johann Beer in 1690:

I say that one can make a fully satisfying harmony with eight persons, namely four vocalists, two violinists, one organist and the director . . . For with six parts there is a complete body of sound, and it is not necessary to trouble oneself further with a larger group . . . 116

Mattheson (1728) duly countered by proposing an ensemble of at least twenty-three persons (plus director), in which Beer’s two violins have turned into what we recognize as an “orchestra.” Yet Mattheson seems content with just the four singers. 117 Lutheran composers were particularly keen to expand their instrumental resources (notably with the newer woodwind instruments), but the essential vocal choir of their concerted music remained in effect the solo-voiced coro favorito of Praetorius , Schütz et al ., with instruments now almost invariably outnumbering voices by at least five to two. 118 (Telemann’s “pool” of singers in Hamburg seems generally to have consisted of seven, alongside twenty or so instrumentalists.) 119 As before, the four or so concertist s – standing well forward 120 – might be doubled from time to time by an optional vocal capella or ripieno group:

Capella is when a separate choir joins in at certain sections for the splendour and strengthening of the Music ; it must therefore be separately positioned in a place apart from the concertists. With insufficient people, however, these capella sections can even be left out, because they are in any case already also sung by the concertists. (Fuhrmann, 1706) 121

The sources of J. S. Bach ’s earliest-known large-scale cantata Gott ist mein König , BWV71 (Mühlhausen, 1708) illustrate these principles with exceptional clarity: the ripieno group – explicitly optional (“se piace ”) – appears in under half of the choral writing. 122 And from the other end of Bach ’s working life, the ripieno parts added in 1742 to Dem Gerechten muß das Licht , BWV195 operate in exactly the same way: concertists remain responsible not only for solo movements but for each and every chorus, with ripienists occasionally added (under certain conditions) simply to add weight. 123 The dozen or more young singers in Bach ’s elite First Choir at Leipzig may perhaps all have sung in the congregational chorales and traditional motets (directed by the Prefect), but his own extraordinarily “intricate” concerted music required only the very best of them to sing. Consequently Bach was able to have the second violin “mostly . . . taken by pupils, and the viola, violoncello and violone always so (for want of more capable persons),” 124 in line with his earlier formal undertaking to “instruct the boys not only in vocal but also in instrumental music, so that the churches may not be put to unnecessary expense.” 125

Female voices

At the Thomasschule Bach faced specific difficulties caused by “the admission hitherto of so many unproficient and musically quite untalented boys,” 126 but dissatisfaction with boy singers was a widespread occurrence and, as we have seen, the cornett had been frequently employed “to supplement . . . trebles, which are not usually good” (Mersenne, 1636). In Glarean’s experience (1547), boys were “frequently unacquainted with the song,” 127 while in Banchieri’s (1614) they were “universally in all cities scarcely to be found, and those with little grounding”; 128 the better ones, according to Mattheson (1739), tended moreover “to think so much of themselves that their behaviour is unbearable .” 129 The main problem, of course, was that “when one has taken great pains to train a boy’s voice, it disappears as the voice breaks, which usually happens between the ages of fifteen or twenty” (Bacilly, 1668) 130 – or at “about thirteen” (Banchieri, 1614). 131 For his concerti ecclesiastici , Viadana (1602) consequently advised that “falsettists will make a better effect” 132 – though within a short time castrati had all but ousted that particular species of soprano from Italy .

For the Church the problem rested on the words of Saint Paul: “Let your women keep silence in the churches” (1 Corinthians 14:34). Rich traditions and high standards of polyphonic music making were nevertheless maintained in many all-female convents, often despite stringent restrictions imposed from outside. In musical publications dedicated to nuns, keyboard transpositions are dealt with by both G. P. Cima (1606) and Penna (1672), 133 suggesting one way of making certain vocal works accessible to female choirs. A double-choir motet by the Modenese nun Sulpitia Cesis (1606) has a different solution: the Tenor of choir I is expressly to be sung up an octave and the Bass not sung but played, as is choir II in its entirety. 134 In music with basso continuo there was an alternative way of tackling vocal bass parts: nuns “can sing the bass at the octave, which produces an alto part” (Donati, 1623). 135 This did not convince a German visitor to Venice in 1725, who “took a strong dislike” to one aspect of the “fugal and contrapuntal” psalm settings as sung by the figlie of the Pietà:

the bass part was sung by a contralto, thereby creating a succession of very clear 5ths and octaves with the continuo bass and with the viola which was beneath the alto part. 136

To a Frenchman, the Italian female contralto was simply

not of the same kind as ours: no type of French voice could render their song well. They are female bas-dessus voices, lower than any of ours. 137

Exactly how Vivaldi ’s SATB writing for the Pietà was performed nevertheless remains somewhat unclear. While several “tenors” and the occasional “bass” are documented amongst the figlie , a significant amount of Venetian ospedale music survives in SSAA format. 138 And when Burney visited in 1771 it seems that music at the Mendicanti was “never in more than three parts, often only in two,” yet very effective. 139 Quite possibly practices varied according both to fashion and to the availability of singers with exceptionally low voices. 140 (An ingenious practice by Vienna’s Ursuline nuns, when no female bass was available, was for a man to sing “through a window [which opened on] to the musicians’ choir.”) 141

The outstanding quality of Venice’s best ospedale singers repeatedly attracted the attention of the city’s many visitors, causing a German courtier in 1649 to reflect wistfully: “I have often wished that the sound of such music might spread to the electoral court chapel in Dresden.” 142 As the demand for elaborate concerted music grew and especially wherever castrati were not an option, one question came increasingly to the fore: “whether it be allowed to make use of female singers in music making in church.” The frequent shortage of good trebles, declared a German theologian in 1721, was something “a good female singer could easily supply”; surely it would be “better if a musically intelligent woman sang devotional arias in church rather than secular and amorous ones at the opera ,” using “this their talent primarily for the praise of God.” 143 Whilst acknowledging that this would be “a vast improvement of chorall musick,” Roger North in 1728 conceded that “both text and morallity are against it.” 144 A proposal in 1762 to admit women as members of the French chapel royal, “in order not to have to send for more Italians” (i.e. castrati ), seems to have been rejected on everything but musical grounds. 145 (As soloists, however, female singers had long been accepted there; Lalande’s two daughters are known to have taken part in grands motets around 1700.) 146

Away from close ecclesiastical scrutiny, the use of “female quiristers” alongside males may have been quietly pioneered in private chapels. An English Jesuit priest gives us a tantalizing hint of clandestine worship in the 1580s at the home of a musical Catholic gentleman: not only were there “choristers, male and female, members of his household” but “Mr. Byrd , the very famous English musician and organist, was among the company.” 147 A century later, various musically skilled chambermaids in the employ of Mlle. de Guise sang the upper parts in her household ensemble (with Charpentier as singer and composer in residence), for both secular and chapel music. 148 By 1717 at least one German court had followed suit: at Württemberg the ten people needed for “a complete and well-set-up” church ensemble included four female sopranos (the younger two designated as “Ripieno” singers). 149

Introducing female singers into Germany ’s municipal churches may have been more of a challenge: “Initially it was required that I should at all costs position them so that nobody got to see them; but ultimately people could not hear or see them enough.” 150 These early experiences of Mattheson’s in Hamburg c .1715 evidently supported his later view that women were “absolutely indispensable” in a Kapelle . 151 Defining a “complete choir . . . for use both in the theatre and in church and chamber,” Scheibe in 1737 was equally adamant that “Of the eight principal singers the sopranos and altos should be women, because their voices will be more natural, and of better durability and purity.” 152 Practice varied, of course, but female singers – soprano and alto, younger and older – are documented at the Würzburg court (1746), 153 at Stuttgart’s Stiftkirche (from before 1720), 154 and, perhaps most remarkably, at Cologne Cathedral (from as early as 1711 and right through the century). 155

Handel

The abiding image of 250 choral singers – just six of them female – packed together in Westminster Abbey for the 1784 “Commemoration of Handel ” 156 raises the question of exactly how large Handel ’s own choirs may have been. Opportunities to write on the grandest scale arose predominantly in connection with royal or state events, yet the “Utrecht” Te Deum and Jubilate (1713), given in the vast spaces of St. Paul’s Cathedral , involved perhaps no more than twenty singers out of an estimated fifty or so performers. 157 It was the Coronation of George II in 1727 that gave rise to the “first Grand Musical performance in the Abbey” and with it some of the most enduring large-scale ceremonial music ever written, not least Handel ’s setting of Zadok the Priest . For the event, the combined Chapel Royal and Abbey choirs reportedly comprised “40 Voices,” 158 while instruments – well over a hundred of them – again outnumbered singers. Music making on this scale, however, was exceptional. 159 The clear majority of Handel ’s Chapel Royal music was designed for St. James’s Palace and for around twenty singers (with occasional modest orchestral accompaniment), while the musical establishment at Cannons (1717–18), where the Duke of Chandos lived “en Prince,” 160 would have reminded him of many a small German court, with its complement of three to eight voices and eight to ten instruments.

Earlier still the 21-year-old Lutheran had left Hamburg for Italy with operatic ambitions. According to a French traveler, accustomed to the lavish vocal forces of Parisian opera , “everyone knows that choruses are out of use in Italy, indeed beyond the means of the ordinary Italian opera house”; instead, any choral writing was routinely delivered by the opera’s various characters, “the King, the Clown, the Queen and the Old Woman – all singing together.” 161 Oratorios worked in much the same way; thus, for Handel ’s La Resurrezione (Rome, 1708), which contains two choruses, we find payments to the solo singers and to more than forty instrumentalists (headed by Corelli ) but none for any additional singers.

In Italy ’s churches, as we have seen, “Renaissance” polyphony (with or without organ) remained current. Major feasts, however, when extra musicians could be hired, 162 routinely demanded up-to-the-minute concertato music – and this is exactly what Handel ’s three Roman psalm settings of 1707 deliver, each in its own way. The original set of parts to Laudate pueri makes it clear that its choral writing was designed for five concertato singers (including the starring soprano) with a “Secondo Coro” of (five?) ripienists, while the concluding double-choir “Gloria Patri” of Nisi Dominus , performed on the same occasion, implies a similar arrangement. In the case of Dixit Dominus , however, the consistently challenging vocal writing nowhere suggests a need for vocal reinforcement of its five virtuoso soloists (despite the single appearance of some chant -like writing marked “cappella ”). 163

A quarter of a century later Handel was turning his attention to the English oratorio . “’Tis excessive noisy, a vast number of instruments and voices, who all perform at a time,” declared an aristocratic lady on hearing Athalia at a London theater in 1733. Yet, although the orchestra was probably at least sixty strong, singers (including six soloists) were estimated to number no more than “about twenty-five.” 164 Messiah (1742) began its remarkable life in relatively modest circumstances, in Dublin’s New Musick Hall, “a Room of 600 Persons.” 165 All indications are that the work’s many choruses were taken by the various soloists (seven of them, male and female) with perhaps half a dozen or so additional singers. Records of subsequent London performances at the Foundling Hospital in the 1750s show payments to five or six vocal soloists, four or six boys and eleven to thirteen other adult male singers, together with the conventionally larger complement of instruments (thirty-three or thirty-eight plus continuo). 166 More interesting perhaps than these numbers and ratios is the “mixed” nature of the resultant choral soprano line: two female “theater” sopranos (usually Italian) and a few Chapel Royal choirboys, doubled by as many as four oboes. (It should be added that the presence of chorus music in the soloists’ books bequeathed by Handel to the Foundling Hospital confirms the expectation of their choral role.) 167

After Handel ’s death in 1759, annual performances of Messiah at the Foundling Hospital continued for many years – as did the institution’s careful bookkeeping. While orchestral numbers remained much the same, what these later accounts clearly document is a sudden and sharp increase in the number of singers from 1771 onwards, when the number of boys rose to twelve and a considerable body of unpaid chorus singers was added – twenty-six or more of them. 168 This moment in the emergence of large non-ecclesiastical bodies of amateur singers, male and female in now-familiar SATB formation, is therefore a fitting place to leave the present brief survey.

From Dufay to Handel , composers of earlier choral music knew their choirs intimately – as choirmasters and directors, and frequently as singers themselves. Pitch levels, singer numbers and ratios, voice types and vocal scoring, conventions of notation and of instrumental participation – rarely do these correspond directly to current practice, yet only exceptionally would any explanation have been required by those for whom the music was carefully crafted. An appreciation of the diverse anatomies of vocal choirs from the first 300 years of modern choral history can only serve to enrich our understanding of the music those composers wrote.

The author is indebted to Hugh Griffith for his expert assistance with various texts and for invaluable advice at the final stages of preparation of this chapter.