Visitors to the royal cemetery at Giza, who stand awestruck in front of that wonder of the world, the Great Pyramid, are usually convinced that its owner, Khufu, was the greatest of the Egyptian pyramid-builders. He was not. That pre-eminence belongs to his father Sneferu, who built no less than four pyramids with a total volume that exceeds the work of Cheops by roughly one third. It was on the orders of Sneferu that the pyramid in Meidum, the Bent Pyramid, the Red Pyramid in Dahshur, and the small pyramid in Seila were raised toward the heavens. Altogether, an incredible 3.6 million cubic meters of stone! Sneferu, later represented by the Ancient Egyptians as a wise and beneficent king, founded the dynasty whose rule and whose feats were to make the deepest impression on the memory of generations succeeding each other on the banks of the Nile. It was an impression to which the sheer weight of the Giza pyramids undoubtedly contributed. The names of Sneferu, Khufu, Djedefre, Khafre, and Menkaure marked out the Fourth Dynasty’s glorious path like milestones and it seemed that there could be no limit to its power. Nevertheless, the dynasty met with sudden decline and fall, and ended in circumstances still more obscure than those in which it attained power. The mysterious tomb, which in Arabic is called the Mastabat Fara’un, is that of the last ruler of the dynasty, Shepseskaf, and it represents a question mark at the end of a famous era. But besides Shepseskaf, there was another figure who came to the fore during the obscure and confused period which set in at the end of the Fourth Dynasty. This figure was that of Queen Khenthaus I In almost every respect she is surrounded by mystery, beginning with her origins and ending with her unusual tomb. Nevertheless, with the progress of archaeological excavations, new information has come to light which makes it ever more apparent that this woman played a key role not only at the end of the Fourth Dynasty but also in the inauguration of the new, Fifth Dynasty.

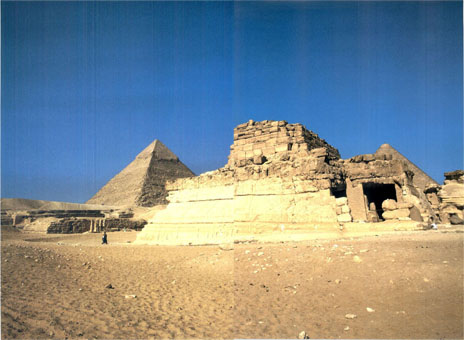

View from the south of the stepped monument of the royal mother Khentkaus I at Giza (photo: Milan Zemina).

When the Egyptian archaeologist Selim Hassan began archaeological research on the so-called ‘Fourth Pyramid’ at Giza in 1932, surprises followed in rapid succession. “The Fourth Pyramid,” a mysterious two-stepped monument on the eastern margins of the Giza cemetery near the Great Sphinx, had attracted the attention of archaeologists as early as the 19th century. For a time it was even considered to be the tomb of the little-known pharaoh Shepseskaf mentioned above. In the 1930s, and shortly before Hassan’s excavations, this was still the belief of such famous experts on the royal cemetery in Giza as Uvo Hölscher, the German archaeologist and architect (who led the investigations of the pyramid complex of the pharaoh Khafre), and the American Egyptologist and archaeologist George Andrew Reisner, whose name is inseparable from research on the pyramid complex of Menkaure and the cemetery that once held members of Khufu’s family. The first surprise brought by Hassan’s excavations was the discovery that the ‘Fourth Pyramid’ was not a pyramid at all but, originally, a rock-cut tomb of mastaba type extended by a superstructure which transformed it into a stepped monument. The second surprise was that it belonged not to a king, but to Queen Khentkaus, at that time unknown, but obviously important, since her tomb was so large and had no parallels among contemporary, or indeed any other, Ancient Egyptian tombs. To the archaeologists of the day, it seemed that light would eventually be shed on the mysteries surrounding Queen Khentkaus and the fall of the famous dynasty but, as it turned out, that was a very hasty presumption.

Even in its original form, Khentkaus’s tomb at Giza was a remarkable and unique building. It was entirely carved out of a rock outcrop and its ground plan, surprising and unusual in tombs of mastaba type, was fundamentally a square of 45.50 x 45.80 meters. The exterior face of the side walls of the superstructure of Khentkaus’s tomb were sloping at an angle of 74° and adorned with a pattern of niches, a motif taken up from Early Dynastic architecture which had mainly employed dried bricks, wood and light plant materials. The niches resembled stylized, symbolic apertures representing entrances to the tomb. They were set all around the tomb and this was related to the concept of ever-multiplying gifts offered to the spirit of the deceased remaining in the tomb.

At a later stage another step, built from limestone blocks, was added to Khentkaus’s rock tomb. This extension was not square but rectangular in plan and oriented the north-south direction. It was not placed over the center of the original building but shifted markedly toward its western part and its roof was not flat, but slightly rounded to facilitate the run-off of rainwater. The entire two-stepped structure, reaching a height of 17.5 meters, was finished with a smooth casing of smaller blocks of fine white limestone, which covered up even the decoration of the original tomb’s outer walls. This unusual form of tomb did not come about by accident but, as we shall see, developed through the extraordinary circumstances accompanying the life of the queen.

East-west and north-south sectional views through Khentkaus I’s tomb (by V. Maragioglio and C. Rinaldi).

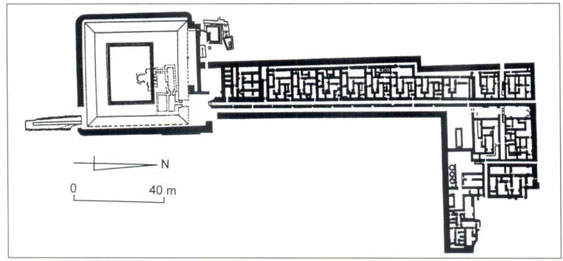

Plan of Khentkaus I’s tomb complex at Giza, including the priests’ settlement (by Selim Hassan).

The generally unconventional impression made by the outer appearance of the tomb is reinforced by its internal design. The mortuary cult chambers were concentrated in the southeastern part of the lower, older layer of the tomb. There were three of these and they were only accessible from the east, via a great gate of red granite originally equipped with heavy wooden doors. On the front face of the gate Selim Hassan found remnants of hieroglyphic inscriptions with the partially preserved titulary, name, and a tiny image of the queen. Of the original relief decoration of the walls of the three cult chambers—which are linked in a series from south to north—only a few fragments have survived; among them is a remnant of the so-called false door, the symbolic passage between this world and the other world, which was set into the western wall of the northernmost chamber.

View of Khentkaus II’s pyramid complex from the summit of Neferirkare’s pyramid (photo: Kamil Voděra).

The underground part of the tomb was laid out in a way that in some respects resembles the substructure of Menkaure’s pyramid. The similarity perhaps reflects something more significant than the proximity of these monuments in time, but its meaning is now obscured—partly because of the damage that has been done to these rooms. The underground part—a large antechamber, several narrow magazines, and above all the burial chamber—was devastated and pillaged by thieves in ancient times, evidently repeatedly. Of the sarcophagus in which the queen’s mummy was once interred only tiny fragments have been found.

Reconstruction of a floral ornament in greenish-blue and black glazed faience from a symbolic vessel which once belonged to the burial equipment of Khentkaus II (by R. Landgrafová).

The tomb complex was, however, much larger than this description suggests and it included other archaeologically important features. Among them was a long narrow trench at the southwest corner of the tomb which originally contained the funerary boat by which the spirit of the deceased was to depart for the other world and float across the sky. At the northeast corner of the tomb there was a pool that was used for purification ceremonies and perhaps even during the mummification of the dead queen. The most noteworthy element was, however, the residential area in front of the anterior, eastern wall of the tomb. This contained the dwellings of the priests who maintained the mortuary cult of the queen in the period of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties.

Khentkaus’s whole complex, in the broadest sense, also included a number of neighboring tombs which were the burial places of people connected with the queen either by family ties or mortuary cult duties. Khenkaus’s two-step tomb became the center of a small but independent cemetery that grew up gradually on the eastern margins of the Giza necropolis. From the archaeological viewpoint this is a remarkable phenomenon; elsewhere in the Giza necropolis it is a demonstrable pattern only in the case of rulers, whose pyramid complexes always represent the centers of satellite cemeteries of relatives, courtiers, officials, and priests—everyone, in short, who desired, and was entitled, to be close to his or her sovereign after death.

The siting of Khentkaus’s tomb very close to Menkaure’s valley temple is a further indication of a possible close relationship between the two individuals. This is a possibility that can only be strengthened by the discovery in Menkaure’s valley temple of a fragment of a stone stele with a damaged hieroglyphic inscription which, according to some Egyptologists, might suggest that Khentkaus was the pharaoh’s daughter.

Plan of Khentkaus II’s pyramid complex at Abusir (by Peter Jánosi).

Among the many extraordinary archaeological discoveries from Khentkaus’s tomb complex, one in particular produced amazement and even a sensation. This was the inscription on a fragment of the granite gate—which has already been mentioned—which contained the never before documented title of a queen. Its discovery immediately raised a fundamental controversy among Egyptologists since, from a grammatical point of view, two interpretations were possible. Some translated the tide as “Mother of the Two Kings of Upper and Lower Egypt,” while others rendered it as “King of Upper and Lower Egypt and Mother of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt.” The historical circumstances of the two suggested interpretations of one and the same title are essentially different. The first interpretation was put forward by Vladimir Vikentiev, the Russian Egyptologist and émigré who at that time lived in Cairo, and the second by the Austrian Egyptologist Hermann Junker who at just that period had started the ambitious Austrian excavations in the cemeteries lying in the shadow of Khufu’s pyramid. It is paradoxical that Vikentiev’s opinion prevailed for such a long time when the discoverer of Khentkaus’s tomb, Selim Hassan, had inclined immediately to Junker’s interpretation. This was perhaps a result of the influence of the Westcar Papyrus, according to which the first three Fifth Dynasty rulers were brothers.

On the basis of all the data gathered during excavations, Selim Hassan drew remarkable—and perhaps rather hasty—historical conclusions. He considered the shape of the tomb, and especially the second step which resembled a huge sarcophagus, to be similar to Shepseskaf’s Mastabat Fara’un. From this formal resemblance he deduced that Khentkaus and Shepseskaf, two figures from the last years of the Fourth Dynasty, had been married. Moreover, he saw in the shape of both tombs, so ostentatiously differing from the pyramid form which prevailed for royal tombs of the period and representing an almost a “religio-political” obligation, an expression of opposition by the ruling royal line to the ever-growing influence of the solar religion and the might of the priesthood of Re. He inferred that, after the death of her husband, Khentkaus finally bowed to the priests of Re and was even forced to marry their High Priest, Userkaf, with whom she then founded the Fifth Dynasty. She refused, however, to be buried next to her second husband and so built her own tomb at Giza in the eternal resting-places of her famous royal ancestors.

Red painted mason’s inscription on a block in the northeast corner of the foundation platform of Khentkaus II’s pyramid. The title of “King’s wife” preceding Khentkaus II’s name was additionally complemented by the title of “King’s mother.” Obviously, the construction of the monument begun by the Queen’s consort was later finished by her son.

As might be expected, Selim Hassan’s researches and his theory attracted not only much attention but also mixed reactions from the scholarly community. One of the first to make a stand was Ludwig Borchardt. Having spent long years of archaeological research in the neighboring necropolis at Abusir, Borchardt immediately realized that the name of queen Khentkaus was familiar to him. The name Khentkaus, preceded by the title “Royal Mother,” appeared on several fragments of papyri which had earlier been discovered in Abusir and which, it was later ascertained, had made up part of the archive of the pyramid complex of the Fifth Dynasty pharaoh Neferirkare (see below. Chapter VI). Not only these fragments of papyri, but also a number of other archaeological finds, such as an alabaster offering table with the remains of an inscription bearing the titles and name of the queen, provided indirect evidence for the cult of a queen mother named Khentkaus at Abusir. A fragment of an inscription on a piece of relief from Mertjesefptah’s tomb at Abusir even makes express mention of Khentkaus’s mortuary temple, which was evidently located somewhere in the Abusir cemetery. The historical conclusions drawn by Borchardt modified Selim Hassan’s theory in many respects. According to Borchardt, Shepseskaf was not of royal origin and gained power only thanks to his marriage to Khentkaus. Their two sons, Sahure and Neferirkare, became legitimate rulers and founded the Fifth Dynasty. The first Fifth Dynasty king, Userkaf, gained the throne only through the premature death of Shepseskaf at a point when the two legitimate heirs to the throne were too young to assume power. Borchardt’s conviction that Sahure and Neferirkare were brothers was undoubtedly influenced by the adjustments to the relief decoration that he discovered during his research in Sahure’s pyramid complex at Abusir (see above, p. 49).

This inscription on a clay sealing from the reign of Djedkare mentions the unique title “Mother of the Two Kings of Upper and Lower Egypt.”

Yet, despite the efforts of Selim Hassan, Ludwig Borchardt, and some other Egyptologists, and indeed partly as a result of their theories and speculations, the reason for the fall of the Fourth Dynasty actually became ever more puzzling. For many years after the initial discovery of the Khentkaus tomb, the subject seemed to have been exhausted. More than a quarter of a century later, however, at the beginning of the 1970s, the problem received fresh attention, this time from the German Egyptologist Hartwig Altenmüller, who re-examined the story of the Papyrus Westcar (see above, p. 70f.) from a literary-historical viewpoint. It occurred to Altenmüller that there could be a tangible connection between Queen Khentkaus and the celebrated Ancient Egyptian literary work preserved in the Westcar Papyrus. He expressed the opinion that the name Rudjdjedet, the earthly woman with whom Re had intercourse and who became the mother of the kings Userkaf, Sahure, and Neferirkare, was a pseudonym for none other than Queen Khentkaus. He then considered the coming to power of her sons as the rehabilitation of the adherents of the solar cult and as the resumption of the rule by the main branch of this pharaonic family.

View of the pyramid complex of the royal mother Khentkaus II from the southwest (photo: Kamil Voděra).

Neither Altenmüller’s theory nor various other attempts to explain the tangled circumstances of the fall of the Fourth Dynasty and rise of the Fifth were free of inconsistencies; nor did they meet with general acceptance within the scholarly circle. On the one hand there was an ever-growing tendency to regard the Royal Mother as a personal link between the two dynasties, though on the other hand she remained the symbol of a complex historical problem: the mysterious fall of a mighty royal line and the no less puzzling rise of a new ruling family and opening of a new epoch in Egyptian history. The confusing array of historical sources and of theories attempting to interpret them finally earned the question its own telling title in Egyptological literature: the “Khentkaus problem.” Most Egyptologists came to believe that the Khentkaus problem” could not be solved unless new information came to light. It was anticipated that any breakthrough would come either from as yet unpublished written sources, lying in the depositaries of world museums for example, or from new finds made during archaeological excavations. This second possibility is the one that has proved fruitful, since finds from the Czech archaeological excavations in Abusir in 1978 and the years following have apparently brought the desired new impetus to the hitherto stagnant discussion of the “Khentkaus problem.”

It is puzzling that, during his work at Abusir, Ludwig Borchardt did not pay more attention to the ruins of a large building near the south side of Neferirkare’s pyramid. Borchardt did, it is true, initiate trial digging, but he suspended further work on the site because he was convinced that the building was a twin mastaba and so an object having no priority in his archaeological research. This was undoubtedly a premature conclusion. The shape of the building, its conspicuous location and orientation by reference to Neferirkare’s pyramid, its clear east-west alignment and several other features evident even from a superficial survey pointed in quite a different direction. They suggested that we are not dealing here with a twin mastaba but with a small pyramid complex, probably belonging to Neferirkare’s wife and consisting of a modest pyramid with a temple in front of its eastern face. One example is the limestone block discovered in the 1830s at Neferirkare’s pyramid by the British engineer and scholar John Shae Perring, to whom Egyptology is indebted for the earliest comprehensive set of descriptions and plans of pyramids. On this block, in red and in a cursive type of writing, was the inscription, “The King’s Wife Khentkaus.” A further example is another limestone block, found about fifty years ago in the village of Abusir by the Egyptian archaeologist Edouard Ghazouli. It had apparently been dragged there from the ruins of Neferirkare’s pyramid temple. Preserved on the block was the remnant of a scene in low relief depicting the royal family. Next to the Pharaoh Neferirkare and his eldest son Neferre (see illustration on p. 54) it shows and names “The King’s Wife Khentkaus.” Archaeological excavations in the area of the ruins of the mysterious building could therefore be initiated, in the second half of the 1970s, in the generally justified assumption that it was probably the small pyramid complex of Neferirkare’s queen, Khentkaus.

Red painted limestone pillars with the remains of hieroglyphic inscriptions containing the name and titles of Queen Khentkaus II (photo: Milan Zemina).

The very first days of the Czech excavation work not only confirmed this theory, but also brought wholly unexpected discoveries. What began to emerge from the millennia-old sand deposits, both literally and figuratively, was not only a previously unknown pyramid complex but also an unknown chapter in the history of Ancient Egypt. It was very quickly confirmed that this was a pyramid connected to a mortuary temple, and it was also demonstrated that the whole building complex had been built and then reconstructed in several phases and that the history of its owner Queen Khentkaus was very much more complex than had been imagined.

Reconstruction of the inscription on a fragment of relief with the titularies of Niuserre and Khentkaus II (by Jolana Malátková).

Construction of the tomb in the form of a pyramid had undoubtedly commenced during the reign of Neferirkare and, as the remains of a cursive inscription on a limestone block in the masonry of the lower part of the monument showed, it had been destined for “The King’s Wife Khentkaus.” Construction work had, however, been interrupted shortly after its beginning, very probably owing to the king’s death. After a break of perhaps two or three years (see above, p. 58f.), the building was completed. On the masonry blocks belonging to this second building stage, however, the original title of the owner of the pyramid, “king’s wife,” was replaced by a new one—“king’s mother.” Apparently, the construction of the monument started by the queen’s husband was completed by a son of the queen.

Detail of a picture of Khentkaus II on a pillar at the original entrance to the queen’s mortuary temple at Abusir. The queen is wearing a vulture headdress and holding in her hands a papyrus scepter and an ankh (by Jolana Malátková).

On completion, the pyramid was perhaps 17 meters high, with sides 25 meters long and walls with an angle of inclination of 52º. The remains of the pyramid that have survived to this day reach a height of perhaps four meters. In the devastated burial chamber underneath the pyramid, no demonstrable fragments of the queen’s physical remains have been discovered (that is, if we do not count a few shreds of linen bandaging which perhaps once swathed a mummified body). A similarly indirect piece of evidence is the small fragment of a sarcophagus made of red granite found in the ruins at the foot of the pyramid.

Detail of a picture of the queen, Khentkaus II, with the uraeus on her forehead. Mortuary temple of the queen in Abusir (photo: Milan Zemina).

Detail of a picture of the queen, Khentkaus II, with the uraeus on her forehead. Mortuary temple of the queen in Abusir (photo: Milan Zemina).

The mortuary temple, built in front of the eastern face of the pyramid for cult reasons, was constructed in two major building phases. The first-phase temple was modest in dimensions although built out of limestone blocks. This earlier “stone phase” of the temple was so extensively destroyed by ancient stone thieves that today it is very difficult to reconstruct its original design in all details. The entrance to the temple was originally from the east, near the southeastern corner and decorated with twin pillars—limestone monoliths colored red and bearing on the exterior side a vertical hieroglyphic inscription in sunk relief with the queen’s titulary, name, and picture. The front, or eastern half, of the temple was taken up by an open court decorated with similar pillars. The center of the queen’s mortuary cult was in the western part of the temple in an offering hall with an altar and false door made of red granite. The false door was embedded in the western wall of the chamber and directly adjoined the pyramid. In front of it offerings would be placed by the mortuary priests. Beside the offering hall and in the westernmost part of the temple were three deep niches in which there originally stood wooden shrines with statues of the queen. A staircase in the southwest corner of the temple gave access to the temple’s roof terrace on which the priests would conduct astronomic observations and certain ceremonies day and night.

The rooms in the western part of the temple were decorated with scenes and inscriptions in colored low relief. The temple’s so-called ‘decorative scheme’ covered an astoundingly wide array of subjects, for example scenes of sacrifice, agricultural work, processions of personified funerary estates bearing offerings to the queen, and others. Among them there are also exceptional themes, such as a scene, unfortunately preserved only in several small fragments, probably depicting the ruler Niuserre and members of his family standing in front of the royal mother. On the fragment with the scene, just as on some other limestone fragments of reliefs and clay sealings, the queen’s name is preceded by a title which is identical to the historically unique title of the Khentkaus buried in the step tomb at Giza: “Mother of the Two Kings of Upper and Lower Egypt” or “King of Upper and Lower Egypt and Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt”! The remains of the inscription on the one pillar still standing in the temple court brought another unexpected surprise. The vertical hieroglyphic inscription with remnants of titles and the name Khentkaus terminates in a picture of the queen sitting on the throne and holding a wadj-scepter in her hand. The queen’s brow is adorned with a cobra rearing to attack, the uraeus. At the time when the queen lived, the right to wear the uraeus on the forehead was the exclusive privilege of the ruling sovereign or of the gods. The ruler was in any case a god, according to the ideas of Ancient Egyptians—the only god living on earth among men. However, it cannot be excluded that the uraeus on the queen’s forehead only indicates that the northern half of the courtyard in which the pillar stood was under the symbolical protection of the Lower Egyptian cobra goddess Wadjet. It is a significant addition to the queen’s iconography, too. Be that as it may, this image of the queen with the uraeus was not to be the last of the surprising discoveries made during the archaeological uncovering of Khentkaus’s pyramid complex.

According to the original plan, the pyramid and the stone mortuary temple should have been enclosed by a high wall built of limestone blocks. However, construction of the surrounding wall was never completed and such parts as had been erected were partially dismantled during the reconstruction and extension of the pyramid complex. The materials obtained from the original wall were used in the building of a diminutive so-called cult pyramid near the southeast corner of the older stone part of the temple. Reconstruction also included the basic extension of the temple towards the east. A new monumental entrance, again adorned with twin limestone pillars, was erected, this time precisely on the east-west axis of the pyramid complex. A small stone basin immediately by the entrance reminded the visitor of the duty of ritual purification before entering the temple. The spacious entrance hall was an important crossroads because it allowed access to a group of five magazines in the southeast corner of the extended part of the temple and to a group of domestic rooms in the northeastern corner; finally, towards the west, it gave access to the so-called “intimate” part of the temple containing the cult rooms. Limestone blocks were not used for the extension of the temple but, this time, the much more economical material of mud bricks. The mud brick walls were, of course, plastered and whitewashed, and sometimes adorned with paintings which at first sight and for a limited time softened the contrast between the effect of the two different building phases.

The meaning of the entire reconstruction project lay in a fundamental change of the conception behind the queen’s pyramid complex. Originally an appendage of the great pyramid complex of Neferirkare, it became the architecturally and functionally “independent” tomb of a person whose rank was similar to that of a ruler. The fragments of papyri discovered in Khentkaus’s pyramid complex indicate that there were at least sixteen statues of the queen standing in her mortuary temple.

The mortuary cult of Queen Khentkaus lasted, if in gradually diminishing form, for perhaps three centuries up until the end of the Sixth Dynasty. During the ensuing first Intermediate Period and disruption of state power, Khentkaus’s pyramid was pillaged. Centuries went by and the abandoned, half-ruined, sanded-up pyramid complex became a convenient quarry from which, as early as the Nineteenth Dynasty, stone was taken for building other tombs not far away. Individual stone-cutters built simple dwellings from fragments of stone within the ruins of the temple. The surprising discovery of Khentkaus’s pyramid complex at Abusir showed that there were two royal mothers named Khentkaus who lived almost at the same time, separated perhaps by one generation only. At the same time, however, it invested the whole series of historical problems known as the “Khentkaus problem” with a new urgency. In particular, two basic questions came to the fore:

1. Were the two queens who bore the rare title of “Mother of the Two Kings of Upper and Lower Egypt” / “King of Upper and Lower Egypt and Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt,” the Khentkaus, from Giza and the Khentkaus from Abusir, one and the same person, or were they two different people?

2. What was the real—or intended—meaning of this unusual title?

Line drawing of the facing picture of Khentkaus I (by Jolana Malátková).

Thorough investigation of this problem seemed to demand, if this was at all possible, a re-examination of the archaeological monuments discovered by Selim Hassan during his research on the step tomb of Queen Khentkaus at Giza. The individual finds that Hassan had not publicized were lying, long forgotten, in some archaeological storehouse in Giza or in the depository of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and it was not feasible to get hold of them again. What remained was only the tomb itself and especially the section in which the remains of inscriptions were still to be found, primarily on the fragment of the granite gate. Careful examination of this inscription, when undertaken with an eye to the information gained in Abusir, nonetheless led to a surprising discovery. Selim Hassan had overlooked a few very small but enormously important pictorial details! Just as at Abusir, at the end of the inscriptions on Khentkaus’s granite gate at Giza there is a picture of the queen under her tide. On the north and south parts of the gate the queen is depicted sitting on a throne, the picture of her on the northern section is damaged but, on the southern section. The picture is complete. Examination of the complete picture showed that to the queen’s head, with its long wig, had been added the so-called vulture diadem, the ornament of Egyptian queens and goddesses, and also a short ritual beard evenly trimmed at the bottom. The ritual beard, fastened to the pharaoh’s face, was of course the exclusive privilege of ruling sovereigns. To the queen’s hand, placed on her breast, had been added a hetes-scepter! There is no doubt that all these changes to the queen’s portrait were made additionally, possibly during the reconstruction of her Giza tomb into a two-step building.

Detail of an inscription on a fragment of the granite gate in front of the southeast corner of the tomb of Khentkaus I at Giza: a vulture headdress, a beard and a scepter were later added to the picture of the queen sitting on the throne (photography by Miroslav Verner).

The unexpected discovery at Giza and the no less unexpected new archaeological materials revealed at Abusir have completely changed our view of the “Khentkaus problem.” Because the unsual tide was thought to have belonged exclusively to Khentkaus I from Giza, when the Czech team commenced the excavation in the pyramid complex of Khentkaus II at Abusir in the late 1970s, and when the first fragments of inscriptions with the title were brought to light, everything seemed to be relatively clear and simple: The monument under excavation at Abusir was thought to have been the tomb of another queen of the same name, Khentkaus II and, at the same time, a sort of a cult place for the famous queen mother, Khentkaus I buried in Giza. However, as the excavation advanced, and different kinds of archaeological and epigraphical materials accumulated, it became obvious that everything was much more complex and difficult than it first appeared. The simple explanation that there was only one queen mother Khentkaus who bore the title became untenable.

The examination of the architectural remnants of the pyramid complex of Khentkaus II did not provide any unequivocal evidence that there was a special part of the building, for instance a room or a false door, reserved for Khentkaus I: neither did the evidence reveal any traces of a cult designed specifically for her. Moreover, the examination of all available written documents—reliefs, sealings, and papyri found in Khentkaus II’s pyramid complex, the papyri from Neferirkare’s mortuary temple and, finally, the inscriptions from the Abusir tombs of priests engaged in the cult of the queen mother—showed that they all referred to Khentkaus II from Abusir. There was thus no support for the theory that Khentkaus I from Giza had a cult also in Abusir. As surprising as it may seem, there were two queen mothers, separated in time by one or two generations, who held the same unusual title. Each of them enjoyed high esteem and a high level cult in the place of her burial.

The answer to the remaining question about the meaning of the unusual tide held by both queens can—at least in the case of Khentkaus II—be inferred, to a certain extent, from the available historical materials from Abusir. These materials surely indicate that Khentkaus II had two sons who became kings, Neferefre and Niuserre, thus giving some raison d’être for the explanation of the tide as “The mother of two kings of Upper and Lower Egypt.” These materials also indicate that some rivalry might have existed between the royal families of Sahure and Neferirkare (see above p. 58f.). According to one of the possible scenarios for the events following Sahure’s death, the king’s eldest son Netjerirenre, the potential heir to the throne, either might have died before his father or, alternatively, may have been a minor. Perhaps it was this situation that facilitated Neferirkare’s claim to the throne.

Neferirkare’s reign, however, was not long enough to stabilize the political situation completely in favor of his family. Moreover, the premature death of Neferirkare’s successor, Neferefre (see Chapter V), could have permitted one of Sahure’s sons an Opportunity to launch a claim to the throne (perhaps as the ephemeral king Shepseskare) at the cost of the claim of Niuserre, the younger son of Neferirkare and Khentkaus II. In such a situation we might see the emerging importance of Niuserre’s mother, Khentkaus II. The role she could have played in Niuserre’s ascension to the throne would then explain her high esteem and the additional enlargement and upgrading of her mortuary cult by Niuserre. It is not excluded that in this complicated dynastic situation, Niuserre was supported by some influential courtiers and high officials, for instance by his later son-in-law and vizier, Ptahshepses (see Chapter VII).

In the case of Khentkaus I the reconstruction of the events surrounding the queen’s life are much more nebulous. She, too, was probably mother of two men who successively became kings, but who they were we do not know with certainty. There are several possible options, including Shepseskaf, Thamphthis, the mysterious last king of the Fourth Dynasty, Userkaf, Sahure, and Neferirkare. In some way, and regardless of all the new archaeological discoveries, the problem of Khentkaus I still remains unsolved.

Fragment of a butchering scene from the temple of Khentkaus II (photo: Milan Zemina).

Uncovering the secrets of the Abusir necropolis (photo: Kamil Voděra).