The Testimony of the Papyrus Archives

Among the scanty Old Kingdom hieratic documents, the Abusir papyri undoubtedly occupy a very prominent position. At first sight, these fragmentary records of the Abusir pyramid temple administration and economy might seem unattractive and dull. However, their meaning for ancient Egyptian history is invaluable. Moreover, the intriguing circumstances of their discovery, and the tricks which fate played with them make of the Abusir papyri an apt subject for a romantic novel.

Today, papyrus only grows in newly established plantations (photo: Kamil Voděra).

Nobody can precisely identify the day on which a group of sabbakhin, the “fertilizer men” from the village of Abusir set out, as they had done so often before, for nearby pyramids on the desert plateau in order to dig there. It was, it seems, sometime in 1893 and the men were certainly not workers on archaeological excavations. The whole situation, indeed, was truly curious with no lack of historical dimension and paradox; the sabbakhin were merely one of its inseparable elements.

In the distant past, four and a half millennia ago when the pyramids were built, unending lines of workmen and bearers traveled up from the Nile Valley to the desert. They would not only carry or drag huge stone blocks large enough to amaze us even today, they would also carry up to the building-site the most valuable of the Nile’s possessions—fertile clay. They would mix it with water and crushed straw and manufacture bricks directly at the building-site. The sun-dried bricks found multiple uses in the building of the pyramid complexes, especially when it was essential to economize or hurry. Sometimes whole temples at the foot of pyramids were built of these mud bricks. After the buildings were completed, smoothly plastered, whitewashed and richly decorated with colored pictures they looked, to begin with at least, as noble and timeless as the stone monuments beside them. Brick buildings, however, rapidly deteriorate. The mortuary cult and the traffic connected with it. sometimes lasting for a whole series of generations, in some cases slowed the decay and in others accelerated it. Another factor was the no less contradictory love of order among the mortuary priests; on the one hand, they were obsessed with ritual cleanliness but on the other they pushed heaps of refuse into back chambers and corners without scruple. This does not surprise or bother archaeologists who, on the contrary, are delighted by the huge layers of rubbish and disintegrated mud bricks which today cover large areas of the pyramid fields. These so-called “cultural layers,” containing, in addition to disintegrated clay, rich organic ingredients, attract the attention not only of archaeologists but, long before them, of sabbakhin For generations these scavengers have been accustomed to daily treks into the desert for the pyramids with hoes and baskets to search for and dig out the “clay” from the “cultural levels,” bringing it back down to the Nile Valley to use as added fertilizer for their small fields and gardens on the edge of the eternally encroaching desert sands. The thousand-year cycle of the circulation of clay between the Nile Valley and the desert by the hands of men thus continues.

On that fateful day sometime in 1893, the Abusir sabbakhin were very successful. They found not only clay to fertilize their fields but also papyri—numerous fragments and larger pieces of scrolls. They rapidly and precisely appraised the rags of papyri with the black and sometimes red inscriptions that they had turned up with their hoes, and evaluated them from the point of view of possible profits on the illicit market in antiquities. As was shown later, they carefully raked over the site of the discovery and gathered up nearly all the papyrus fragments which they then sold to Cairo dealers in antiquities. It was not long before the papyri turned up on the Egyptian antiquities market. They were very rapidly snapped up by experts who immediately realized their overall value. Some of the papyri ended up in the Egyptian museum in Giza, whose collections were only at the beginning of the century transferred to the then recently completed and now central Egyptian museum in Cairo. Others came into the possession of foreign Egyptologists, especially Henri Edouard Naville and William Matthew Flinders Petrie. The remarkable journeys of the papyri did not, however, end there.

Transportation of fertile soil on the back of a donkey (photo: Kamil Voděra).

At the end of the 1890s, German archaeological excavation commenced in the remains of the great sun temple of the Fifth Dynasty king Niuserre to the north of Abusir in the locality of Abu Ghurab. The German expedition was led by Wilhelm von Bissing, but the excavation was directed by the then young architect and archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt. Borchardt had been interested in the Abusir pyramids for some time and, in connection with the excavations at Abu Ghurab, he had developed a particular interest in the pyramid of Niuserre, which had been identified and briefly described more than sixty years before by the English scholar John Perring. It was very probably the chance discovery of the papyri mentioned above that led Borchardt to the firm decision to start extensive archaeological excavations at Abusir immediately upon finishing his work at Abu Ghurab.

The excavations at Abusir took place between 1900 and 1908. Before Borchardt began his excavation, a German Egyptologist named Heinrich Schäfer had attempted to locate the original site of the discovery of the papyri in just seven days of trial digging—without results. He searched around Neferirkare’s pyramid, since the papyri clearly indicated Neferirkare’s pyramid complex as the place of their origin.

Mme. Paule Posener-Kriéger was present at the excavations in Neferefre’s mortuary temple at Abusir at the moment that the most beautiful of Neferefre’s statues was discovered (photo: Milan Zemina).

Borchardt’s first attempt to find other papyri in 1900 was likewise unsuccessful, despite his considerable archaeological experience, knowledge of local conditions, and rare ability to obtain valuable archaeological information from the native inhabitants. It was only in February 1903 that he managed to find several fragments of papyri, just a few square centimeters in size, in the ruins of Neferirkare’s mortuary temple, in the storerooms east of the southeast corner of the king’s pyramid. Borchardt had certainly expected to find a larger deposit of papyri, but it would be wrong to speak of a complete disappointment. Among the fragments was one which Hugo Ibscher, the celebrated papyri restorer from the Berlin Museum, managed to join together with a piece of papyrus found by the sabbakhin ten years before. The origin of the papyri and even the place in which the sabbakhin had found them was therefore conclusively established.

The Abusir papyri had generated great excitement in specialist circles, and world museums with large collections of Ancient Egyptian antiquities had expressed interest in diem. For this reason they did not long remain in the hands of Naville, Petrie, and others who had come into contact with them and they ended up in London, Berlin, Paris and also, of course, in Cairo. In London they were acquired by two institutions—the British Museum and University College. Similarly, in Berlin some of the papyri are today to be found in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (the former East Berlin) and some in the Staatliche Museen der Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (the former West Berlin). In Cairo they were simply shifted from one bank of the Nile to the other, from the former museum at Giza to the Egyptian Museum opened in the center of Cairo in 1900. The movements of the main state collections of Ancient Egyptian antiquities within the boundaries of modern Cairo were in fact rather more complicated. Originally, it was decided by the Egyptian government that the collection created in 1858 and located on the east bank of the Nile in the Bulaq quarter should be transferred to the Giza quarter on the west bank. Finally, the collection was taken to the Egyptian Museum on the east bank.

The fragments of papyri which ended up in Paris, in the Museé du Louvre, had made a particularly remarkable journey. Although it sounds unbelievable and especially odd in view of the excited attention which they attracted from expert circles immediately on their discovery, they only came into the possession of the Louvre in 1956 and it is only from that year, more than half a century after their discovery, that serious research on the Abusir papyri began. It was also in 1952 that the librarian of the Bibliotheque de la Sorbonne, Louis Bonnerot, randomly opened a journal that had originally belonged to the celebrated French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero, a former director of the French Institute for Oriental Archaeology in Cairo. The journal was inherited by the library after Maspero’s death. Two quite large fragments of papyri fell from the journal and thus came to the attention of Bonnerot. The distinguished Paris expert on papyri, Georges Posener, professor of Egyptology at the Sorbonne, identified them as part of the find made at the end of the previous century by the sabbakhin at Abusir. Only subsequently were the fragments transferred to the Museé du Louvre.

This time the interest excited in Parisian Egyptological circles by this small but historically significant discovery did not fade away. At Posener’s instigation his student, later his wife, Paule Kriéger began to take a more systematic interest in the Abusir papyri. In 1956 she managed to find further papyrus fragments in the Louvre, in a folio deposited with other books of Maspero’s in a trunk which had been transferred from the Bibliotheque de la Sorbonne four years before. From that moment. Paule Posener-Knéger’s career was to be inextricably linked with the fate of the Abusir papyri.

The attention attracted by the discovery of the Abusir papyri and their rapid plunge into obscurity was due to several factors. As has already been mentioned, the papyri consisted of fragments, altogether numbering a few hundred, and these fragments ranged in size from small pieces to major parts of entire scrolls. In the course of time, at the end of the 1930s and beginning of the 1940s, several small fragments had in fact been published by various scholars in connection with work on a number of subsidiary questions in Ancient Egyptian history.

For instance, after Selim Hassan’s surprising discovery of the tomb of the Queen Khentkaus I in Giza. and the heated debate among scholars incited by the queen’s unique tide of the “Mother of Two kings of Upper and Lower Egypt” or “The King of Upper and Lower Egypt and Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt,” Borchardt decided to publish a fragment of papyrus which he had found in Neferirkare’s mortuary temple which mentioned the “King’s mother Khentkaus.” It seemed to be logical to identify the queen Khentkaus from Giza with the king’s mother Khentkaus mentioned on the fragment of papyrus from Abusir. At the time nobody knew that Neferirkare’s consort was also named Khentkaus. and that her small pyramid complex lay only about 50 meters from the place where the papyrus fragment was found. Moreover, Borchardt’s article led to the conclusion, widely accepted by scholarly public, that Neferirkare was a son of Khentkaus from Giza and one of the two kings mentioned in her unique title. The second king mentioned in the queen’s title was identified as Sahure. This identification was made because of some additionally altered reliefs in Sahure’s mortuary temple on which Kurt Sethe—a famous German Egyptologist who translated the inscriptions discovered by Borchardt in Sahure’s pyramid complex—based his assumption that Neferirkare and Sahure were brothers. Though not supported by contemporaneous sources, the theory that Sahure and Neferirkare were sons of Khentkaus I then became established history.

A facsimile of the text with the name and title of the “King’s mother Khentkaus.” From the fragment of papyrus found in Neferirkare’s mortuary temple.

However, let us return to the Abusir papyri. The first essential condition for scientific examination of the papyri was to order and classify them and to put together the parts that belonged to each other. This first step, apparently purely mechanical but in fact requiring long-term preparation and a basic grasp of the content of the individual fragments, was so difficult that at the beginning of the century nobody was willing to embark upon the task.

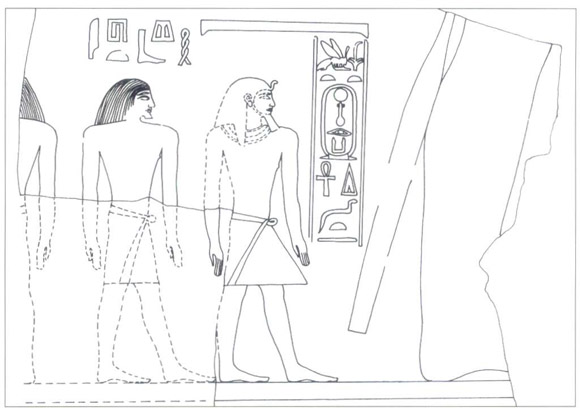

Fragment of a relief from Sahure’s mortuary temple. Shows a man in Sahure’s entourage whose picture was subsequently altered into the pharaoh Neferirkare (by L. Borchardt).

Another serious formal obstacle was represented by the texts themselves, and more precisely by the type of script used to make the records on the papyri. It was the early cursive type that today we call Old Hieratic. It was derived from hieroglyphic writing and used particularly on occasions when it was necessary to make a record quickly, simply and without ostentation, for example for the purposes of administration. The record was made with a small brush, most often in black but in special cases red and most frequently on a small sheet of papyrus but sometimes on a fragment of limestone, a shard of pottery, a wooden tablet or even an animal bone. It was a kind of writing that could turn into a scrawled line when the scribe was in a hurry, and this, of course, further complicates matters for the reader. The difficulties of reading Old Hieratic are increased still more by the fact that only a relatively limited number of examples exist. This means that the reader must have a thorough knowledge of the script and of the mechanism by which individual signs were simplified.

Scribe’s palette of greenish slate found at Tell al-Ruba’a. Egyptian Museum in Cairo (JE 35762) (photo: Kamil Voděra).

Additionally, the actual content of the hieratic records on the papyri in itself constituted a major obstacle. As at last became clear, they were records of very diverse-kinds, from accounting documents on management of the temple cult to royal decrees. It is therefore no wonder that the Abusir papyri were only to “give utterance” three quarters of a century after they were found. When they did so it was thanks to the lifelong efforts of the late Paule Posener-Kriéger, formerly Director of the French Institute for Oriental Archaeology. Her efforts were supported by the encouragement and professional advice not only of Georges Posener but also of the British Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner—who even arranged for her a scholarship to edit the papyri—and, last but not least, by the Czech Egyptologist Jaroslav Černý, also a distinguished expert in hieratic paleography.

After more than twenty years of intensive work Paule Posener-Kriéger, in collaboration with the Museé du Louvre’s long-time custodian Jean Louis de Cenival, published the set of papyri discovered in Neferirkare’s pyramid temple and scattered in the aforementioned museums. The work, known as The Abusir Papyri, published in the form of an independent volume in the British Museum Series of Hieratic Texts in 1968, included a list of papyri, photocopies, hieroglyphic transcriptions of the hieratic texts, and relevant paleographical tables. Eight years later Mme. Posener-Kriéger added a translation and commentary. Under the title Les archives du temple funéraire de Néferirkare-Kakaï the two-volume work came out in 1976 in the Bibliotheque d’Études series published by the French Institute for Oriental Archaeology in Cairo. With these two volumes the richness of Neferirkare’s temple archive was at last made accessible to the expert public.

The edition showed above all that the papyri represent only a fragment of the archive of Neferirkare’s pyramid temple and that they are all in one way or another related to the pharaoh’s mortuary cult. In several cases, the dating of the papyri has been made possible. As a matter of fact, on some of the papyri both the name of the king who issued the documents and the date referring to the year of the census of the country’s wealth, the so-called cattle count, are present. Unfortunately, more precise dating of the documents is impossible because in the Old Kingdom the census took place irregularly, sometimes annually, sometimes biennially.

The papyri have thus been dated to a period between the concluding phase of the Fifth Dynasty and the end of the Sixth Dynasty, in other words, roughly to a period from the beginning of the twenty-fourth to the end of the twenty-third century BCE. The fact that a large proportion of the papyri have been identified as dating from the reign of Djedkare (only a smaller part of the papyri date from the reigns of Unas, Teti, and Pepi II) may be closely linked to the fact that it was this monarch who decided not to build his pyramid complex at Abusir, in the cemetery of his immediate royal predecessors, but several kilometers away in South Saqqara. Whatever Djedkare’s reasons for building his tomb in another place were, the decision to abandon the Abusir necropolis obliged the king to undertake meticulous regulation both of the running of the mortuary cults in the individual pyramid complexes and of the general conditions in the necropolis. This is the background to which the large number of papyri dating from the time of Djedkare is related.

From the point of view of content, the papyri of Neferirkare’s archive can be divided into several categories. Let us mention at least some of them.

One group is represented by rosters of priestly duties in Neferirkare’s pyramid temple. These were tasks carried out daily in the morning and in the evening, monthly, or on the occasion of important festivals. They consisted of bringing offerings to the spirit of the deceased, sacrificial rites, and guard duties in various parts of the mortuary temple, among other activities. Particular services would be undertaken on the occasion of religious festivals such as the festival of Sokar (on the twenty-sixth day of the fourth month of the inundation season), during which this god of the dead visited the Abusir valley temples in his barque and was received there by the dead kings. Another festival, that of the Night of Re, undoubtedly preceded the feast of Re and probably took place-in Neferirkare’s sun temple on New Year’s Day—although we do not know whether this was on the lunar or civic New Year’s Day. The festival of the goddess Hathor was celebrated both in Neferirkare’s mortuary and sun temples during the inundation.

According to the papyri, the priesthood in the mortuary temple was made up of the “servants of god (prophets),” “the pure,” and the khentyu-sh, “the tenants” (the translation and interpretation of this Egyptian name is still the subject of academic debate). Various officials and workers and others would help them in the performance of their dudes. The priesthood was divided into five basic groups, the so-called phylai— designated in terms of the parts of a boat, for example “prow—starboard,” “stern—port,”—which were subdivided further into sections. Perhaps forty priests would make up one group. The lists suggest that the offices and professions represented among the priests and employees of the mortuary temple were extremely diverse; there were, for example, hairdressers, physicians, and scribes.

Fragments of a decree issued by Djedkare. Neferefre’s mortuary temple archive (photo: Kamil Voděra).

Hieroglyphic transcription of the hieratic text of a decree issued by Djedkare (by P. Posener-Kriéger).

The inventory lists, which were a way of keeping track of the internal furnishings and equipment of the building, are very valuable in giving a better picture of the internal arrangement of the mortuary temple. Figuring in the lists are a whole range of different types of vessels, offering tables, ritual knives, materials, oils, jewelry, boxes, precious cult instruments, and incidental items. For each Object there is a record, in a special column, indicating whether the object is or is not in its correct place, and whether it is damaged. Everything was recorded, from a wooden column in the temple courtyard damaged by fire to a broken pot. The bureaucratic throughness and precision of the priests and officials was so extreme that they did not hesitate to record that a small hall of incense was in its proper place in a box!

Accounting documents make up a large group of the papyri. Records concerning the supplies of various products and objects and their use or storage, documents pertaining to financial transactions and suchlike are only superficially dull. Deciphering them offers a unique key to understanding the complex mechanism by which the economic basis of the temple functioned. The wider economic context emerges here with unusual precision and sometimes brings surprises. They record yields from the estates specially allocated to provide material support to the pharaoh’s mortuary cull; these included supplies of bread, cakes, beer, milk, wine, fruit, vegetables, fats, poultry, and meat. Naturally, they also mention other provisions such as cloth, staffs and maces, furniture, and much else.

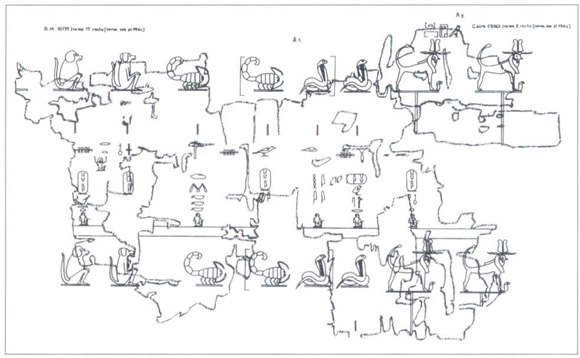

Fragment of papyrus from Neferirkare’s mortuary temple archive with emblems of deities—a griffin, the cobra goddess Wadjet, the scorpion goddess Selket, and the baboon god Benet. The emblems, belonging to cult objects kept in the temple, were carried on the occasion of certain ceremonies that took place at the Abusir necropolis (by P. Posener-Kriéger).

From the documents it is clear that supplies to the temple did not only How in from the funerary estates that the king had set up during his lifetime to meet the needs of his mortuary cult. They also came from the stores of the royal residence, palace, and some other important central institutions. Among them, a special place was occupied by supplies from sun temples, especially Neferirkare’s sun temple. These supplies had already been offered up on the altar of the sun god and only then were they taken to be offered on the altar of the deceased king in his pyramid temple. The sun temple of Neferirkare, though abundantly mentioned in the Abusir papyri, has, however, not yet been found, even though it was obviously located not far from Abusir.

Of the quite small group of surviving documents not yet mentioned, those directly related to the architecture of the pyramid complex have a special significance. These contain very heterogeneous and scrappy information connected, for example, with the regular sealing of doors in individual parts of the temple for purposes of inspection, the checking of possible damage to the temple’s masonry, and other such matters. However fragmentary, this information acquires concrete archaeological importance when set side by side with the temple’s real physical remains as uncovered during excavations. For example, in the papyri of Neferirkare’s temple archive there is an allusion to damage being sustained to the masonry of” the South Barque during a service performed by one of the groups of priests. There is also an even more fragmentary mention of the North Barque. The assumption that two buildings—a South and a North Barque—had existed in the precincts of Neferirkare’s pyramid complex became, at end of the 1970s, the starting-point for interesting archaeological research by the Czech team at Abusir. With the help of geophysical measuring, it proved possible to find and partially uncover the eastern half of a large, boat-shaped building in mud brick that had stood by the south wing of the enclosure wall of the pyramid, and precisely on its north-south axis. The building was originally about 30 meters long and contained a wooden boat in which the dead king could symbolically travel to the other world and join the entourage that accompanied the sun god on his eternal journey across the heavenly ocean. Unfortunately, all that has survived of the barque is moldering dust. The North Barque has not been uncovered, even though knowledge of the principles of Ancient Egyptian building suggests that it was extremely likely to have been situated—entirely symmetrically in relation to the South Barque—by the north enclosure wall of the pyramid.

By a curious coincidence, in 1976, the same year that Posener-Kréger’s book on the temple archives of Neferirkare was published, the Czech archaeological team in Abusir commenced excavation in a small pyramid complex situated about 50 meters south of Neferirkare’s pyramid. Very soon, the complex proved to be the tomb of Neferirkare’s consort Khentkaus II (for further details see Chapter IV). The monument was badly damaged by stone robbers who had quarried away large portions of pyramid and most of a small limestone temple at the foot of the pyramid’s east wall. In the debris filling the open pillared courtyard of the temple other fragments of papyri were found. At first sight, the papyri seemed to be of the same kind as those found just a few meters away, in the southwest storerooms of Neferirkare’s mortuary temple. The remnants of a small wooden chest were found close to the papyri in which the latter may originally have been kept.

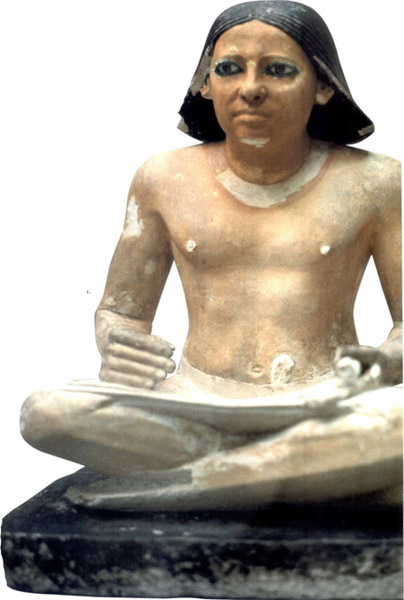

Seated scribe writing on a papyrus scroll supported on his skirt, which is stretched tight between his knees. Polychrome limestone, 51 centimeters high. Egyptian Museum in Cairo (no. 36) (photo: Milan Zemina).

The papyri from Khentkaus II’s temple represent the second papyrus archive found in Abusir. It consisted of about one hundred fragments, most of them very small. Only a few pieces were as large as a human palm. These papyri, too, were examined by Posener-Kriéger, and published by her in our joint volume The Pyramid Complex of Khentkaus. Today the papyri are in the Egyptian museum in Cairo.

Alabaster tablet of “the seven offering oils” found in the mastaba of Khekeretnebty at Abusir (photo:Milan Zemina).

Though the name of the royal mother Khentkaus does not occur on any of the fragments, the texts drat survived leave no doubt that they made up part of the queen’s temple archive. On five fragments there is a representation of a female figure-standing in a shrine, wearing a vulture head-dress and holding in her hand a was-scepter. Since no specific attributes of a divinity accompany the figures on the fragments, this image most probably represented the owner of the mortuary temple herself, Khentkaus II. Moreover, the fragments of texts seem to indicate, quite strongly, that the pictures represent Khentkaus’s cult statues. Thanks to the detailed description of materials from which the statues were made, we learn that the naos was of wood and decorated with lapis lazuli, the queen’s necklace was of gold, the eyes were inlayed with onyx, the was-scepter was made of electrum, and so on. The papyri also indicate that in the mortuary temple there were originally at least sixteen cult statues of the royal mother. Regardless of all these details, the kind of the document from which the fragments come remains rather obscure. They may have originally come from a sort of an inventory of the temple cult objects.

If Neferirkare’s temple archive had remained shrouded in mystery and the precise archaeological circumstances of the discovery remained unknown, then the third papyrus archive of Abusir, found in Neferefre’s mortuary temple, was in this respect the complete reverse. It was possible to record carefully every detail of the archaeological context in which these papyri were discovered and, consequently, to bring together a mass of important supplementary information. Major assistance with unearthing and documentation of the papyri was provided to the Czech expedition by the late Paule Posener-Kriéger. By a lucky coincidence, shortly before the discovery of the papyri in Neferefre’s mortuary temple, she had been appointed the director of the French Institute for Oriental Archaeology in Cairo. Our joint efforts were successful and over 2000 fragments, including entire large sections of papyrus scrolls, were retrieved, documented and provisionally lodged in the storage facility of the Czech expedition at Abusir. Because of security reasons, the papyri were moved to the Egyptian museum in Cairo before the end of the season.

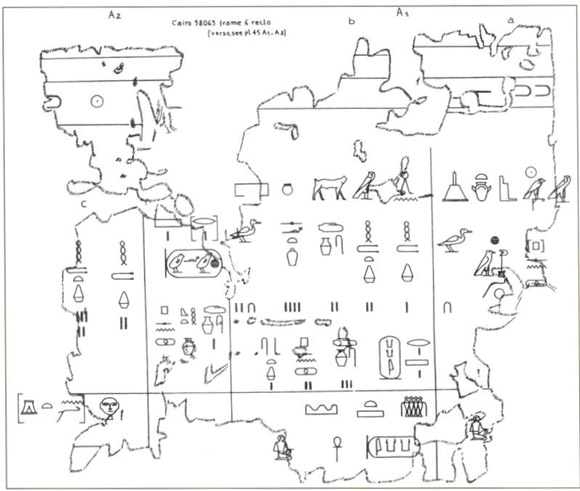

The text on a fragment of papyrus from Neferirkare’s mortuary temple mentions, among other things, deliveries coming from the king’s sun temple (by P. Posener-Kriéger).

The papyri were found in several different places of Neferefre’s mortuary temple. The largest number were found in the storage rooms in the northwest part of the temple. There were so many there that their fragments had created an almost continuous layer on the floor of three of the storage rooms. The papyrus scrolls had originally been fastened with leather straps and lodged in wooden boxes. It is probable that later, when the temple was ransacked, thieves regarded the ornamented boxes as valuable but ignored the papyri. The contents of the boxes were tipped out onto the ground and, in the course of time, the papyri were trampled underfoot, submerged in rubbish and covered over by layers of crumbled, collapsing brick masonry from the rooms. Finally, everything was engulfed by vast layers of sand which safely preserved the remains of the papyri for four and a half millennia.

Facsimile of the remnants of the picture of Khentkaus II’s statue standing in a naos. From a fragment of papyrus found in the mortuary temple of the queen.

It is almost unbelievable that these papyri, fragile as a spider’s web, have survived to this day. Originally, of course, they were elastic and robust. This was a consequence both of the material—the pulp of the papyrus stems—and the technology for producing the scrolls. They were made by laying narrow strips cut from papyrus pulp crosswise over each other. No glue was used to stick the strips together since the papyrus juice, squeezed out from the pulp under the pressure of a stone press and then gradually dried out, was sufficient to bind the strips together.

The scribe’s activities—both the method of writing and the writing materials used—in no way damaged the structure of the papyrus. The records were made with a small brush prepared from a thin reed stem, the end softened by chewing and formed into a tip. The scribe dipped the brush either into black ink (made of soot diluted with water) or into a red ink prepared from powdered ochre, likewise mixed with water. This meant that, when necessary, the text could be removed with water. The scroll could then be used again for making another record. A whole range of such re-used papyri, known as palimpsests, was found among the fragments from Neferefre’s archive. Of course, if a papyrus scroll was exposed to the action of water for a longer time, or was left in damp conditions, it would be entirely destroyed.

In the case of Neferefre’s temple archive a number of fortunate accidents occurred and these contributed to the preservation of the papyri, albeit in a fragmentary state. The first of these was the layer of dust and rubbish that had already covered the fragments at the time when the rooms in which the papyri lay were still roofed and were therefore still watertight. Another happy accident was that the brick masonry of the rooms progressively disintegrated and gradually settled on the layer of rubbish covering the papyri. In the end. this layer was so thick that it was not damaged by the collapse of the side walls, with their larger volume and weight, as a result of erosion. The huge layer of sand blown onto the ruins of the temple by the desert wind also proved ultimately beneficial, because it hid the papyri and the ruins from sight.

In overall volume, Neferefre’s archive is comparable to that of Neferirkare. Though with certain divergences, the basic content of the surviving documents is also similar. For example, a higher number of royal decrees, often regulating the economic conditions of certain categories of the temple priesthood, have been preserved in Neferefre’s archive. Most of these decrees, if not all of them, seem to have been issued by Djedkare.

Experienced workmen carefully uncovering and lifting fragments of the papyrus archive of Neferefre’s mortuary temple (photo:Josef Grabmüller).

The major part of the papyrus archive was found in three magazines in the furthest northwest corner of Neferefre’s mortuary temple (photo: Kamil Voděra).

Surprisingly, a relatively high number of documents with dates has survived, more than in Neferirkare’s temple archive. Most of them seem to refer to Djedkare’s reign, some of them possibly to the time of Unas, too.

Of course, among the papyri one can also find documents with rosters concerning the service in Neferefre’s mortuary temple. They contain detailed information on the organization of the temple priesthood, schedules for the service of different phylai in the temple, lists of responsible officials, and so on. A variety of personal names and titles, many of them intimately known to us already from Neferirkare’s temple archive, are mentioned in these papyri. Of special importance are the names of officials whose tombs have already been identified and unearthed in Abusir. Concerning the titles, perhaps one of the most curious temple professions documented in Neferefre’s temple archive was undoubtedly the ‘flute-player of the White Crown”—a man who played the flute during the ceremony connected with venerating the crown that symbolically made the pharaoh the ruler of Upper Egypt.

As in Neferirkare’s temple archive, accounting documents form a large portion of the papyri found in Neferefre’s temple. They inform us in detail about the supplies coming to the temple from the funerary estates, the royal residence, the temple of Ptah and, most significantly, from Neferirkare’s sun temple. As a matter of fact.

Inventory lists represent another group of papyri in Neferefre’s archive. These documents, which mostly relate to regular revisions, help us to get a better idea of the temple’s inventory, which included a variety of objects from cult statues to different instruments used in the temple rituals. Thanks to one of these lists we know that in the Neferefre’s temple inventory there were, for example, wooden statues of a statues of a heron and a hippopotamus. Neferefre’s sun temple was, at the moment of the king’s untimely death, only just begun, and was never finished. Some of these accounting documents are especially interesting and important.

Incomplete scroll of papyrus from Neferefre’s temple archive with a list of cult objects. Among the objects kept in the temple were wooden statues of a heron and a hippopotamus (plum.: Milan Zemina).

Eventually, a brief mention at least should be made of one very significant archaeological aspect of the papyri found to date in Abusir. Some of the documents explicitly mention edifices which must have once existed in the Abusir necropolis and which have not yet been identified. For instance, the “Southern sanctuary,” the palace named “Sahure’s-splendor-soars-to-the-sky,” and others. It is not necessary to emphasize what a great archaeological challenge these documents provide for Egyptological scholars today.

Hieroglyphic transcription of the hieratic text regarding the cult objects kept in Neferefre’s mortuary temple (by P. Posener-Kriéger).

What remains to be said? We should perhaps express regret that other papyrus archives are unlikely to be discovered at Abusir. The discovery of the remnants of three temple archives—those of Neferirkare, Neferefre and Khentkaus—has been to some extent a matter of chance and the coincidence of a few unique historical circumstances. Under normal conditions the analogous papyrus archives of the royal pyramid complexes were not kept in the storerooms of the mortuary temples, but in the administrative buildings, which, together with the priests’ dwellings, were concentrated in the immediate vicinity of the valley temples, i.e. in the so-called pyramid towns. In other words, they were kept not in the tomb complex but still in the “world of the living,” although in close proximity to the entry to the “realm of the dead.” At Abusir such towns, in which priests, officials and workmen employed in the mortuary cults at the cemetery lived and worked, almost certainly existed in the vicinity of Sahure’s and Niuserre’s valley temples. Their remains lie today perhaps five meters beneath the surface of the desert, under great layers of Nile mud deposits. The current level of ground water in these places lies about one meter beneath the surface. This means that the papyrus archives in the administrative buildings of the pyramid towns have long disappeared without trace, dissolving and moldering into the mud that cradles them. It was only by sheer accident that Neferirkare did not finish his pyramid complex and that this was accomplished for him by his younger son, Niuserre, who then had the causeway leading from the valley to the mortuary temple of his father diverted and completed as a part of his own pyramid complex. The tombs of the older members of Niuserre’s family, all by coincidence unfinished and only completed in his reign, were thus consigned to a somewhat autonomous and isolated position within the cemetery. For that reason their priests did not make their dwellings near valley temples on the edge of the desert, but in the immediate neighborhood of the mortuary chapels and gradually, even inside them. The higher site of the mortuary temples, perhaps 30 meters above the Nile Valley, and the hot and dry conditions of the desert had then only to interact favorably for the remains of the papyrus archives to be preserved to this day.

Seshat, the goddess of writing. Low relief from Sahure’s mortuary temple at Abusir (by L. Borchardt).

Head of a statue of the

vizier Ptahshepses. The vizier

wears a wig on his head and

a beard on his chin. Reddish

limestone, 23 centimeters high

(photo: Milan Zemina).