South Abusir: At the Crossroads of History

For about two hundred years, the vast Memphite necropolis has attracted the attention of countless archaeologists and it belongs, without any exaggeration, to the best archaeologically examined areas in the world. However, it does not mean—and this has been repeatedly emphasized in the previous chapters—that there are no “white-spots” on the archaeological map of the necropolis. Indeed, surprisingly large areas remain as yet unexplored by archaeologists. The same cannot be said, however, for the robbers and their “mapping” of the Memphite necropolis antiquities. Both these statements are illustrated by a large cemetery identified by the Czech team in South Abusir in the late 1970s.

Topographically, South Abusir is an area adjacent from the north to Wadi Abusiri, a shallow valley running approximately northeast-southwest that separates in the Memphite necropolis at Saqqara from the cemeteries of Abusir. To the south, the valley is flanked by the escarpment of North Saqqara on which is situated the Early Dynastic-élite cemetery excavated by J. E. Quibell, C. M. Firth, and W. B. Emery. At the foot of the North Saqqara escarpment lies another, socially one step lower, cemetery of upper middle class Egyptians from the same period: that was excavated by H. Bonnet.

Further to the southwest and deeper in the desert lie the royal tombs of the Second Dynasty. Unfortunately, these Second Dynasty royal monuments, the largest of which is Qisr al-mudir “Director’s enclosure” (this bizarre name, pertaining to Auguste Mariette Pasha, was given to the monument by the local men who worked for him not far from here, in the Serapeum, in the early 1850s) remain as yet largely unexplored. To date, only the underground galleries, which once probably belonged to the tombs of Ninetjer and Ranch, have been examined. Considering all these topographical and archaeological circumstances, there is no wonder that Wadi Abusiri is considered by some Egyptologists to have been the easiest and, in the Early Dynastic-Period also the principal access way to Saqqara-a son of gateway to the then royal necropolis.

In antiquity there was, very probably, a large lake close to the mouth of Wadi Abusiri. As a matter of fact, a lake called by the local people Birket Mokhtar Pasha—simply known as the Lake of Abusir by modern archaeologists—existed there as late as the time of the construction of the Aswan dams which terminated the annual Hoods in the Nile valley north of Aswan. The lake (recorded, for example, on the archaeological map of Abusir by Lepsius’s expedition in the early 1840s) was probably a natural water basin, the level of which fluctuated with the height of the Nile floods. Unfortunately, the precise location of the Early Dynastic Period Old Kingdom lake has not yet been identified. Nevertheless, the results of drill cores carried out along the Saqqara escarpment by British archaeologists within the Egypt Exploration Society’s Memphis Project seem to suggest that in the Early Dynastic / Old Kingdom limes there were two lakes, one near the valley temple of Unas and the second near the Abusir valley temples. The lakes were separated from each other by a high dry shelf. Possibly, considering the annual siltation and other environmental factors, the Early Dynastic / Old Kingdom lake of Abusir may have lain a bit farther to the east, under the gardens and fields of the present village of Abusir. In any case, the mere existence of two landing ramps—one on the east and one on the south—instead of only one standard eastern ramp in both Sahure’s and Niuserre’s valley temples seems to anticipate a water way in the southeasterly direction from the temples. If so, it would have been the shortest and the most direct communication between the Abusir pyramid complexes and the large urban center in Memphis, which also included the Temple of Ptah—an institution of vital economic importance for these complexes, as can be inferred from the Abusir papyri.

View of Smith Abusir from the North Saqqara escarpment. In the background the pyramids of Abusir and, behind them, the pyramids of Giza are visible (photo: Milan Zemina).

There are still some other factors to be considered concerning the location of the ancient Lake of Abusir. One of them, for example, is the surprising absence of any buildings on a large raised plateau between South Abusir and the Abusir pyramid field. Did some important installations around the surmised lake (for instance, the royal palaces; see above, p. 150), prevent this prominent place of the Memphite necropolis from being used for building purposes?.

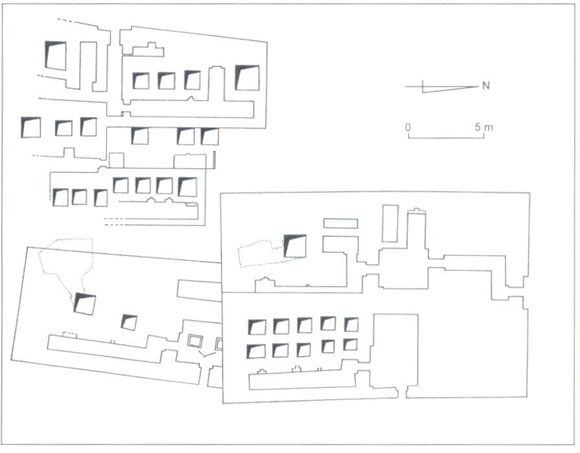

Plan of Kaaper’s mastaba (above) and Ity’s mastaba in South Abusir (by M. Barta).

According to some Egyptologists, it was just this lake and funerary and religious cults thriving around its western shore that could have given an impetus, at the beginning of the historic age, to the establishment of the then elite cemetery in the North Saqqara / South Abusir area. As a matter of fact, some scholars incline towards identifying the Lake of Abusir with the mythical lake of Pedju mentioned in the Pyramid Texts—the oldest group of Ancient Egyptian religious texts. It is also thought that the cult of the falcon god Sokar (the god of the dead and ruler of the local cemeteries, and the deity to whom Saqqara probably owes its modern name) arose in close proximity to the Abusir Lake. Moreover, the area with underground catacombs in North Saqqara (and, possibly, also in South Abusir) has been identified with the mythical “Fields of Reeds”—the Elysian Fields of the Ancient Egyptians and the realm of Usir (Gr. Osiris), Lord of the dead. After all, the name “Abusir” is only the Arabic interpretation of the Greek version of the original Per-Usire, “the place of Usir’s worship.”

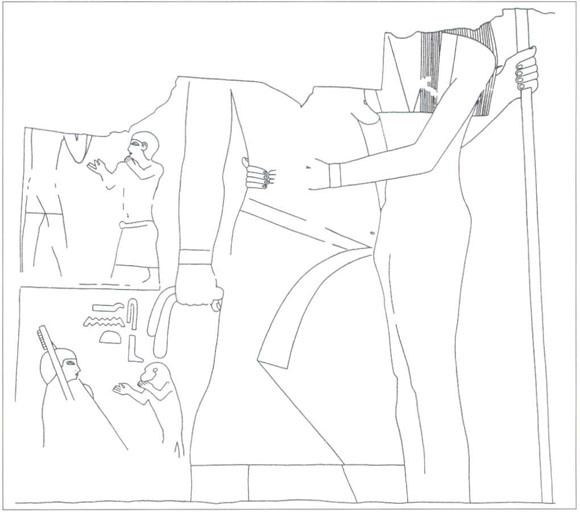

Kaaper in the embrace of his consort. A fragment of a scene in low relief from the chapel of Kaaper’s mastaba (by H. G. Fischer).

Though the precise location of the Early Dynastic Period capital of Egypt, Ineb(u) hedj (“The White Wall(s)”), has not yet been identified, an opinion prevails among Egyptologists that it probably lay not far from North Saqaara / South Abusir namely, somewhere to the north of the temple of Ptah (significantly in this context, the god worshipped in the temple was called “Ptah-south-of-the Wall,” i.e. the White Wall) in Mit Rahina and just opposite the escarpment with the Early Dynastic elite cemetery. Moreover, the results of long-standing explorations have led archaeologists to the ever increasing conviction about a much closer physical association in the Memphite region between the east and west, the capital and the necropolis, than presumed so far. It seems, as the scholars L. Giddy and D. Jeffreys believe, that the Early Dynastic urban center spread along the eastern bank of a natural water basin which facilitated rather than blocked direct communications with the cemeteries lying west of the basin.

The paramount archaeological importance of the South Abusir area was one of the reasons for the rather cautious approach of the Czech team to the opening of the field work there. As a matter of fact, it had originally been planned to begin the systematic exploration of the South Abusir cemetery only after the conclusion of the excavations in and around the so far unexamined Abusir pyramids namely, those of Neferefre and Khentkaus II, and Lepsius nos. XXIV and XXV However, recent activities from tomb robbers were discovered in South Abusir in the late 1980s, and this accelerated our decision to research in this area. As a matter of fact, a close examination of the site revealed fresh traces of the robbers’ digging in two places. One place lay on the top of a hillock in the southernmost outskirts of Abusir, about five hundred meters to the north of the famous mastaba of Ti, the second a bit farther to the northwest. As the excavations were to show fairly rapidly, the first place hid the ruins of Kaaper’s mastaba, the other those of the large family tomb complex of Qar.

Shortly before the Czech excavation of the mastaba of Kaaper began in 1991, ten blocks—left on the site by the robbers—had been hastily moved to the storage-rooms of the Antiquities Inspectorate in Saqqara by the inspectors of antiquities. The first finds made in the mastaba of Kaaper, though seriously damaged by the robbers, took the Czech team by surprise: the tomb belonged to a well known Old Kingdom official named Kaaper, a scribe of the king’s army. His name and picture are famous in Egyptology thanks to the American Egyptologist Henry G. Fischer’s brilliant article published more than thirty years ago. As a matter of fact, Fischer drew remarkably detailed conclusions in his article about not only Kaaper and his career but, at the same time, the original decoration of Kaaper’s tomb. The conclusions were based on just a few photographs that he received from Zakariya Ghoneim, the then chief inspector of antiquities in Saqqara. Moreover, Fischer succeeded in finding in various American collections (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art. Kansas City; The Institute of Arts, Detroit; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) blocks with reliefs that originally belonged to the tomb and were acquired by these museums in the years after World War II.

Even more recently, during preparations for publication of the final edition of a work concerning the archaeological materials unearthed in Kaaper’s tomb, more blocks coming originally from this tomb and now scattered in various collections abroad (Foundation Martin Bodmer, Geneva; Bible Lands Museum, Jerusalem; a block published in Sotheby’s catalogue, 1996) were identified by Miroslav Bárta of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Surprisingly, one of the recently identified blocks from Kaaper’s mastaba was found more than one kilometer to the south of the tomb by Ian Mathiesson and his collaborators from the Saqqara Survey Project of the National Museums of Scotland when they were surveying the area around Qisr al-Mudir All these loose blocks largely complement the scanty remnants of the original decoration in situ in a chapel, the only room besides the serdab in the southeast corner of the mastaba’s superstructure.

At the beginning of the Fifth Dynasty, Kaaper, judging by the titles, which represent a major part of the inscriptions so far revealed from his tomb, was an influential dignitary. He was “the inspector of the treasury.” “property administrator of the king,” “overseer of all works of the king,” and so on. Besides these titles linking Kaaper with the top administration, there are, in his titulary, two groups of titles that deserve special attention. The titles of “the herdsman of dappled cattle” or “the scribe of the pasture lands of the dappled cattle” indicate that Kaaper was a high official controlling cattle breeding, which was at that time concentrated mostly in the border regions of the Delta. The other group contains important military titles such as “the scribe of the army.” “the inspector of all the bowcase bearers,” and “the scribe of the army in Wenet, Sera; Tepa, Ida, Terraces of Turquoise, and the Western and Eastern foreign lands.” Except for the Terraces of Turquoise, the designation for the turquoise mining site of Wadi Maghara in Sinai, and Tepa, perhaps a settlement in Nubia, the precise identity of the other localities remains unknown so far. Wenet, Serer and Ida might have been fortified military camps with Egyptian troops near the northeastern border of Egypt. According to Barta, it seems likely that these fortresses helped control the routes which connected the Delta with South Palestine and Sinai and which were of vital importance for Egypt. The Syro-Palestinian wine jars found in Kaaper’s burial chamber may attest to the tomb owner’s administrative engagement in the northeastern border of Egypt. As a whole, the titles seem to indicate that in his time Kaaper was probably one of the key figures in command of the militarily and economically important border regions of Egypt.

In the underground section of Ity’s mastaba (photo: Kamil Voděra).

The underground part of the tomb, involving a shaft and a burial chamber, must have been visited and looted by robbers at least twice in antiquity, for the first time at the end of the Old Kingdom and the second time in the Roman Period. The last attempt to penetrate Kaaper’s burial chamber can be relatively precisely dated to the mid-1960s, judging by a piece of Arabic newspaper and a fragment of a bakelite lamp found in the shaft. From the few remnants of Kaaper’s burial, it is worth mentioning a limestone ear that, very probably, was originally part of the so-called reserve head, a rather mysterious clement of the burial equipment whose precise meaning is still being debated by Egyptologists. If so, it would be the second reserve head found so far in Abusir, the first being that found by Borchardt in the Mastaba of Princesses built near Niuserre’s pyramid.

To the east of Kaaper’s tomb, two large mastabas of a different type and date than the former were unearthed by the Czech team in the 1990s. The owner of the first mastaba, adjacent from the east to that of Kaaper, was identified only thanks to the lucky find of a small, badly eroded libation basin still firmly embedded in the floor in a small chapel in the southeast corner of the mastaba’s superstructure. The remnants of an inscription on the basin revealed that the tomb belonged to “the overseer of the two granaries of the Residence, Ity.” The superstructure of Ity’s tomb has a core made up of pieces of limestone surrounded with a mud brick mantel, the faces of which are decorated on all four sides with recesses. The substructure involves two burial chambers, independent of each other, planned originally for Ity and his spouse. The northern, corridor-shaped chamber was accessible by means of a twisted stairease, whereas access to the larger, southern chamber was via a vertical shaft. Unfortunately, both underground systems were plundered as early as antiquity. The infrequent finds of pottery help date the monument to the early Fourth Dynasty.

Hetepi, “the speaker of the king.” A detail from the relief decoration of Hetepi’s mastaba in south Abusir (photo:Kamil Voděra).

The mastaba of Hetepi can be dated to approximately the same time as Ity’s tomb, the late Third / early Fourth Dynasty. It was unearthed farther to the east than Ity’s tomb. Hetepi’s type of tomb resembles in many respects regarding its structure and building materials used that of Ity. In the southern burial chamber, fragments of a wooden coffin and the skeleton of the tomb owner were found. The remnants of the decoration, including a fine funerary repast scene with inscriptions elegantly carved in low relief on a limestone slab, came to light in Hetepi’s chapel, which was located in the southwest corner of the superstructure. These helped identify the tomb owner as Hetepi, “strong voice of the King,” “one of the Great Ones of Upper Egypt,” and so on.

As previously mentioned, the second place in South Abusir to have been recently damaged by robbers hid a large family tomb complex of the vizier Qar, dating from the time of Pepi I and the early reign of Pepi II. The vizier had quite a curious name, since “Qar” means in Egyptian “the handbag”; nonetheless, this whimsical name proved to be very popular at the beginning of the Sixth Dynasty. The date of Qar’s tomb corroborates the theory concerning the horizontal stratigraphy of the tombs in the South Abusir cemetery: it seems that the earlier tombs lie in the east whereas the later ones lie in the west. Moreover, the farther from the Wadi Abusiri, and the deeper in the desert, the Lower the social rank of the tomb owners can be expected.

A line-drawing of the inscriptions from the false door of Qar (chapel no. 1) (by Jolana Malátková).

Though already repeatedly plundered repeatedly in antiquity, the inscriptions and other archaeological materials from the family tomb of the vizier Qar brought the Czech team a number of archaeological surprises. Moreover, they introduced the archaeologists to the so far little known and, as it seems, rather turbulent political period at the beginning of the Sixth Dynasty.

The part of the complex so far unearthed involves, besides the tomb of the vizier Qar, also those of his sons Senedjemib and Inti, born apparently of different wives. (Other members of Qar’s family were buried in shafts arranged in row in the western part of the vizier’s tomb.) So far unresolved remains the problem of the tomb of Qar-junior, who predeceased his father. As a matter of fact, two chapels in the complex of Qar were revealed, one is undecorated (no. 1) but the other (no. 2) has a nice polychrome decoration in low relief (mostly scenes of bringing the offerings). Each chapel has a false door hearing, besides the funerary formula, the name and titles of Qar. However, the false doors differ from each other in some important details. Except for being more carefully executed, the false door from chapel no. 2 bears not only more but, at the same time, more important titles. The false door from chapel no. 1 belonged to Qar, who held merely the tide of “the ‘true juridical official and mouth of Nekhen” (an old and high juridical tide to be perhaps more precisely translated as “speaker of Nekhen /i.e. the Upper Egyptian citadel of Hierakonpolis/ belonging to the Jackal /i.e. the King/”). On false door no. 2, Qar bears the titles of “the vizier,” “the overseer of the Six Great Law-courts,” and so on, as well as “the ‘true’ juridical official and speaker of Nekhen” (the latter title being mentioned in the inscriptions on both false doors in a prominent place). Thus the question is: did both chapels, and both false doors, belong to one and the same person namely, Qar-senior (which would be rather unusual) or, did the undecorated chapel, though not directly connected with the burial shaft of Qar-junior, belong to the vizier’s son? We shall return to the problem below.

Qar’s false door (chapel no. 2) (photo: Kamil Voděra).

Inti’s consort Merut seated at the foot of her husband smelling a lotus flower. A detail from the polychrome relief decoration in Inti’s tomb in south Abusir (photo: Voděra).

View of Inti’s burial chamber with a large limestone sarcophagus which was probably robbed immediately after Inti’s burial (photo: Kamil Voděra).

The vizier’s burial chamber contained a large, box-shaped sarcophagus in limestone that contained the skeletal remains of the tomb owner. Except for potsherds, nothing has survived from the original burial equipment. However, anticipating the future robbers’ activities and the gloomy fate of the physical items of the burial equipment, the walls of burial chamber were inscribed with long lists of offerings needed for the vizier’s welfare in the Other World.

Recently unearthed, the tomb of the vizier Qar’s son Inti lies adjacent and to the south of his father’s tomb. This, too, yielded further important archaeological material. Here again, in the west wall of the chapel, an intact limestone false door bearing Inti’s name and titles was found in situ We learn from the inscriptions that Inti was A fragment of a limestone block with the sculptures and tides of Meriherishef found in the ruins of Inti’s tomb in South Abusir (photo: Kamil Voděra). “the supervisor of mortuary priests in the pyramid complex of Teti,” “the judge of the Six Great Courts,” and so on. It seems that in many respects Inti copied the official career of his father. Among the remnants of nice polychrome low reliefs of great workmanship there survived in the chapel a delicate scene of Inti’s spouse sitting at his feet and smelling a lotus flower.

A fragment of a limestone block with the sculptures and titles of Meriherishef found in the ruins of Inti’s tomb in South Abusir (photo: Kamil Voděra).

Some archaeological finds and observations seem to indicate that Inti’s burial chamber might have been plundered, probably with the consent of the necropolis guards, immediately after the placement of the burial in the sarcophagus and the conclusion of funerary ceremonies. To the hasty work of the robbers we possibly owe the finding of a number of less precious items from Inti’s burial equipment, such as symbolical miniature offering vessels in alabaster and miniature models of copper instruments.

As briefly remarked above, the inscriptions revealed on the two false doors in Qar’s tomb complex posed a problem the solution of which is not unequivocal. Moreover, provided that both false doors belonged to Qar-senior, the inscriptions might touch, as the Australian Egyptologist Vivienne G. Callender working with the Czech team in Abusir presumes, on an unusual event that happened in the reign of Pepi I namely, a trial of a queen. We learn about the trial from the autobiography of Uni, a high official who lived in the time of Pepi I and Merenre. Uni had on several occasions been entrusted by his lords with some special tasks (for example, a number of military expeditions against the Palestinians, the provision of a rare stone for the construction of the pyramidion of the king’s pyramid, the digging of a channel in the area of the first Cataract, and so on). No doubt, however, the most delicate of his missions was the trial involving a queen for some crime (a plot in the royal palace concerning the succesion to the throne?). In the trial, which took place during the early reign of Pepi I and involved the Six Great Courts, Uni was assisted by an anonymous judge, a Speaker of Nekhen. The latter might have been Qar-senior, in which case this event would explain his rapid career. If so, the provision of Qar’s tomb might reflect the subsequent upgrading of his social position. In addition, the distinction of “true” being added to his title of “the juridicial official and speaker of Nekhen” would be explained.

Wall painting with a scene depicting vineyard workers and men trading in a market. Documented in Fetekti’s tomb in South Abusir by the Lepsius expedition in the early 1840s. The tomb painting is no longer in existence.

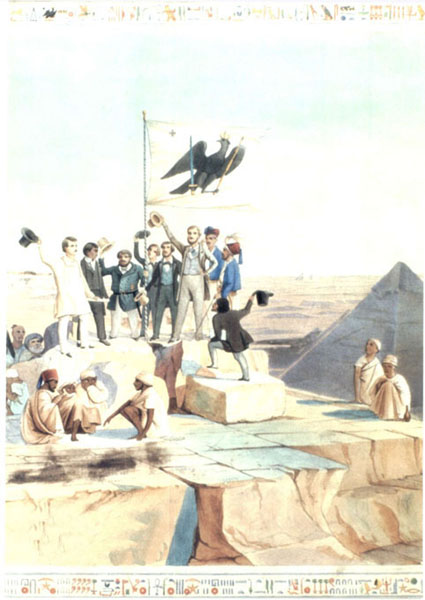

As a rule, major finds fill archaeologists with joy and enthusiasm rather than sorrow. However, the latter was certainly the feeling that prevailed in the Czech team at the moment of the discovery of the tomb of Fetekti. Perhaps, it would be more precise to say “the re-discovery,” since the tomb had already been unearthed during trial diggings made by Lepsius’s expedition in Abusir in 1843. Unfortunately, these diggings were never described in detail nor precisely located on the expedition’s archaeological map. The small, late Fifth / early Sixth Dynasty tomb of Fetekti, “the property custodian of the king,” was in a way an exception, owing to its very attractive decoration. A few of the wall paintings, such as the vivid scenes of wine pressing, trading in the market, etc., were published in Lepsius’s Denkmákr aus Aegypten und Aethiopien Since the 1840s, however, the tomb has been lost. No wonder that its identification in the vast region of South Abusir became one of the objectives of the Czech team, the more so because Fetekti is very probably one of the same-named officials mentioned in the papyri of Neferirkare’s temple archive. Eventually, the tomb was identified on the southeast slope of the plateau separating the Abusir pyramid field from the South Abusir cemetery. It was not a happy discovery, however, for unfortunately, all the beautiful wall paintings published in Lepsius’s Denkmáler were no longer in existence: after the paintings had been copied, Lepsius’s expedition apparently left the tomb open and the wind and rain obliterated those fine and detailed paintings.

Plan of the lower-middle social strata in the vicinity of Fetekti’s tomb in South Abusir (by J Krejči and K. Smolárikova).

Fetekti’s tomb makes up part of a lower middle class cemetery that dates from the late Fifth and early Sixth Dynasty and extends along the eastern slopes of the plateau between the Abusir pyramids and the South Abusir cemetery. The tombs unearthed so far in this cemetery were entered through a small open courtyard (or, a pillared vestibule as was e.g. Fetekti’s tomb). They involve a long, narrow corridor-type chapel and several burial shafts in which the less important members of the tomb owner’s family were buried. The owner of the tomb had a roughly hewn burial chamber in the underground part of the tomb. To date, besides Fetekti’s tomb the tombs of Hetepi, “the overseer of the storehouse,” Isesiseneb, “the juridical official and speaker of Nekhen,” Rahotep, “the director of the estates.” and Gegi, “the land-tenant,” have also been unearthed. Farther to the north, the tomb of Shedu, “the overseer of sweets in the pyramid complex Enduring-are-the-(cult)-places-of-Niuserre” was excavated. Shedu’s tomb is adjacent from the west to a large anonymous tomb built of mud brick and dating from the late Third or early Fourth Dynasty. The cemetery around Fetekti’s tomb once again confirms how densely built with funerary monuments the whole area, which extends outwards from the eastern outskirts of the desert, from the mouth of Wadi Abusiri as far to the north as Abu Ghurab and, undoubtedly, still farther on, is. It also shows how complex its stratigraphy in that part of the Memphite necropolis is.

Youssef, a conservation specialist from the Saqqara Inspectorate of Antiquities, rescuing the remains of wall paintings in Fetekti’s tomb (photo: Kamil Voděra).

The last decade of the field work in the South Abusir cemetery, briefly reported above, was very demanding (the excavation was immediately followed by large-scale restoration and reconstruction of the tombs) but, at the same time, very exciting, as well. Nevertheless, the quantity and importance of new historical evidence from this so long forgotten corner of the Memphite necropolis is amazing. Though our research is only beginning, South Abusir proves that it indeed represents an important crossroads of Ancient Egypt’s history.

The Lepsius expedition on the top of

the pyramid of Cheops: Lepsius’ birthday

celebration (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Preussischer Kulturbesitz. Picture reproduced

by kind permission of Dietrich Wildung).