1

The Cost of Democracy: First Benchmarks

DEMOCRACY rests on a promise of equality, which too often shatters against the wall of money. We tend to forget that providing for democracy comes at a price. This is not necessarily very high in absolute terms—which shows, by the way, that a rational collective solution is within reach. But if the costs are very unevenly distributed, and if the weight of private money in the total funding is not severely restricted, then the whole system is in danger.

In this first chapter, we shall review the evolution of election spending in recent decades in a number of countries, beginning with France, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States. In some cases, this spending is mainly charged to the candidates themselves, who are then reimbursed by the state in full or in part; this happens especially in countries that use a first-past-the-post system, with one MP per constituency. In countries with a system of proportional representation, the parties support the bulk of campaign spending and serve as an intermediate body between the public coffers and the candidates. Campaign funding and party funding: the heads and tails of the ringing coinage of democracy, which, as in Perrault’s fairy story of the donkey with golden dung, keeps multiplying.

As we shall see in later chapters, however, what really counts is who produces the coinage. Public funding or private donations: depending on which it is, the same level of campaign spending can reflect diametrically opposite realities. For in politics, donkey dung is rarely silent when it is made of gold. And the weight of private donations can prove heavy to bear.

The Price of Elections

Democracy is first of all elections. What gesture can be simpler or less onerous than to slip a ballot paper into a box? To go to a polling station one Sunday en famille seems an act uncontaminated by the logic of the market. Polling stations are the schools of the republic. The attendants are ordinary citizens, just like you or me, who have chosen to give a little of their time to democracy. The only condition is that they should be on the electoral register. There’s no gain from it—except the satisfaction of taking part in a democratic high mass, scheduled to finish in time for evening mass at 8 o’clock, or of counting the votes in boxes that are often too empty. How long ago seem the days when you had to have some property to vote!

What, then, is the cost of elections? In 2016, a victorious candidate for the US Senate spent on average more than $10 million.1 In France, the average parliamentary candidate reckons on much less: a little more than 18,000 euros in 2012,2 although the figure rises to 41,000 euros for the lucky winners. In the United Kingdom—where, as in France, there is a legal ceiling on campaign expenditure—the average for the general elections in 2015 was 4,000 euros, rising to 10,000 euros for those who came out on top.

Such is the real cost of elections: campaign spending by the candidates plus spending by parties and interest groups.3 The money that each of these puts on the table to convince voters of how they should vote is spent on a range of methods such as public meetings, leaflets, house-to-house canvassing, publicity campaigns, and—to an increasing extent—the direct purchase of space and visibility in the media and social networks. In the last few decades, such expenditure has been continually growing in a number of democracies, with the exception of those that regulate it.

The gap between election spending in the United States and in the United Kingdom or France is clearly not due to cultural differences. It is not the case that we have, on the one side, austere Brits worried over the money spent on leaflets with the parsimony familiar from Ben Jonson’s Volpone and, on the other side, the Great Gatsby, willing to spend as if there were no tomorrow to win over his fellow Americans. Nor do the differences in question reflect a greater taste for electoral contests on the other side of the Atlantic. If the sums spent could be equated with the degree of popular interest in elections, then the highest spending ought to go together with the highest degree of commitment. But of all the Western countries, the United States has the lowest voter turnout. The differences in campaign costs are not cultural differences; they are the direct result of election laws that have lasting, and often neglected, effects on the structure of the democratic process.

High-Cost Democracy

How much is a parliamentary candidate willing to put on the table to have a chance of winning? To answer this question, we first need to ask another one: How much is an election candidate permitted to put on the table? The amount not only varies from country to country but also fluctuates sharply from period to period.

Is the Feast Over?

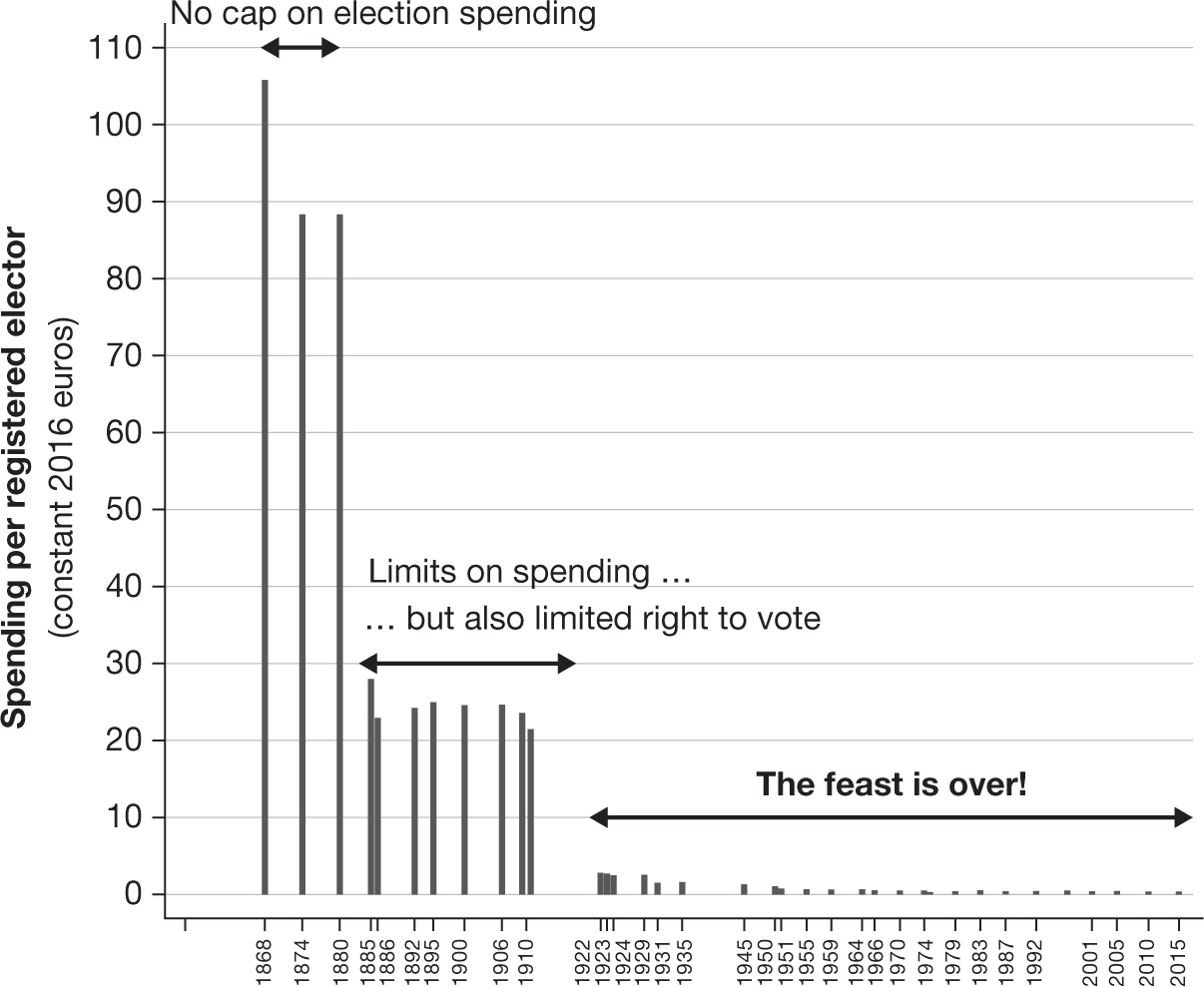

A first, seemingly evident fact is that, if no limits are set, candidates tend not to limit themselves and are capable of spending sums that beggar belief. To grasp this fully, it may be helpful to look back at the nineteenth century. In the United Kingdom, one of the first countries to limit election spending with the Corrupt Illegal Practices (Prevention) Act of 1883,4 the total expenditure of parliamentary candidates (expressed in today’s euros, adjusted for inflation) regularly exceeded 200 million euros: 191 million in 1868, 184 million in 1874, and 228 million in 1880. This was more than ten times the sums spent today—even though there was a smaller number of voters to “convince,” and the real national income per adult was nearly five times lower. Before a ceiling was placed on election spending in 1883, it could sometimes rise above one hundred euros per voter. Today, by comparison, the total amount spent per voter registered for British parliamentary elections varies between 0.40 and 0.50 euros per election (Figure 2).5

This nosedive in election expenditure appears even more clearly if it is expressed as a proportion of national income per adult: in 1868, each candidate spent on average a little more than 185,000 euros, or thirty times the annual national income per adult head of the population! This suggests that—over and above the suffrage restrictions—only the richest citizens could aspire to stand for seats in Parliament. Today, however, the average spending of a candidate in parliamentary elections represents scarcely more than 10 percent of per capita national income.6 In other words, expressed in terms of national income per adult head of the population, the average spending of candidates has been divided by 262 in the course of the past 150 years. Such a radical cut needs to be explained.

Figure 2. Total spending of candidates per registered elector, UK parliamentary elections, 1868–2015

If the total election spending of all candidates in UK parliamentary elections in 1868 is divided by the number of people on the electoral register, the spending per elector amounts to 105 euros (in constant 2016 euros). The spending per elector was 21.50 euros in the 1911 parliamentary elections, and 0.35 euros in those of 2015.

Are candidates perhaps more “honest” in their way, more determined to convince people through their ideas than through electoral propaganda? Or is the decline in spending linked to new campaign technology, especially the use of (less expensive) social networks? On the other hand, what could tens of thousands of euros per candidate have been used for in the nineteenth century, when radio and television did not exist, and when it is hard to imagine candidates having recourse to highly paid communication consultants? There is no lack of spicy examples in the history books, such as the fact that transport for voters was one of the main items of declared expenditure. (For a long time, moreover, candidates often directly reimbursed voters for their transport costs—though God forbid we should see this as a possible source of corruption!7) Voters’ transport might include not only first-class train tickets (often cheaper than carriage hire) but also overnight hotel accommodation and compensation for loss of pay due to turnout at the polls. It is interesting to pore over parliamentary debates of the time and listen to MPs argue that if voters had to pay for such things themselves, they would simply not bother to cast their ballot.

The truth is that if British parliamentary candidates spend little on elections today, it is because they are not authorized to spend more. The law has made its move—which is a good thing—and limits possible excesses. If candidates could flood the online media and social networks—as they were able, a century and a half ago, to win the support of voters installed in comfortable couchettes—there is every reason to think that they would do so. The US presidential campaign in 2016, with the suspicions of foreign interference that followed it, is a clear sign that this is the direction in which we are heading, as is the scale of campaign spending in a number of other countries.

But I saw you raise an eyebrow. Is a cap on expenditure really a good thing? Libertarians of every stripe will jump from their padded chairs and bang the table: “Why shouldn’t I be allowed to do what I like with my money? Why should I spend just a few tens of thousands of dollars when I’m in a position to spend millions? Let the others do the same if they want!” Is it really necessary to discuss this argument? Citizens are not equal when it comes to the size of their pockets; they do not all have the same funds to spend on their campaign, or the same possibility to raise them from elsewhere. To allow all candidates to spend as much as they like is tantamount to introducing a new property qualification. For only those rich enough or with the right connections would be able to stand—or, more precisely, to stand with more than a zero chance of being elected. This immediately raises several questions about the representativeness of candidates selected in this way. We shall see in Chapter 11 that in a democracy like the United States, where each candidate’s campaign spending literally runs into the millions, the ostensible people’s representatives cannot be said—if we consider their socio-occupational origins—to represent any but the wealthiest sections of society. In other words, ordinary workers are the main groups missing from the parliamentary benches. The United Kingdom, though never close to parity, does a little better in this respect: 20 percent of MPs were of working-class origin in the period after the Second World War.

Excessive campaign spending also entails a major danger of corruption. A politician is all the more prone to accept kickbacks and other secret money if she has to spend several millions to have any chance of being elected.8 The game changes if campaign spending is entirely covered by the public purse: candidates are then encouraged to spend roughly equal amounts, and above all they do not have to sacrifice their convictions or integrity in the chase after money. As a matter of fact, proposals for a cap on campaign spending have often been considered alongside the public funding of elections.

Cap Spending, but Fund Elections

In France, election spending has been limited by law only since 1988 in the case of national elections (and since 1990 for local elections).9 Although the rules have been slightly modified since then and vary from election to election, the ceiling on expenditure essentially depends—as in the United Kingdom—on the number of people on the electoral register. Moreover, candidates are restricted in how they are able to use their funds. Candidates at an election in France may not—even if they have the means—buy publicity for themselves on television or radio.10

The other side of this is that the state bears a sizable share of campaign costs, since candidates receiving more than 5 percent of the votes in the first round may have their spending reimbursed up to nearly a half of the capped amount. This refunding of campaign expenditure was introduced at the same time as the ceiling on expenditure. Nor is this a peculiarity of France. In Canada, the Election Expenses Act of 1974 both introduced tight limits on the campaign spending of parties and candidates and provided for the reimbursement of expenditure.11 The same was true in Spain, where the first constitutional election law was enacted in 1975.

Of course, the reimbursement of election spending does not necessarily go together with the existence of a ceiling, although anyone who advocates reimbursement out of the public purse automatically favors a cap on (at least refundable) expenditure. The state, unlike many private donors, does not have bottomless pockets. So those who support reimbursement from the public purse will logically support a cap on private contributions and therefore on campaign expenditure. Otherwise, what would be the point of publicly funded reimbursement of expenditure if this was in the end drowned beneath a flood of private money? (We shall see that one of the main weaknesses of the German model, despite its generous support for political parties, is precisely that it does not limit private donations, so that ultimately the economic policies of any government reflect the interests of the auto industry—which, taking its lead from BMW, funds all the parties each year—more than those of the majority of German citizens.) The public funding of election campaigns is a tool for fighting the corruption of electoral life; to be complete, the arsenal requires tight regulation of the size of expenditure.

Regulation of election spending does not necessarily imply its reimbursement. A low ceiling can be set on what candidates are allowed to spend, without the state’s necessarily bearing the cost of some of that spending. This is the case in the United Kingdom, as we have just seen, and it is also the case in Belgium. In fact, Belgian election law does not provide for any system of public funding or reimbursement of election expenditure.12 Yet such spending has been tightly capped ever since 1989, so that during an election period parties can spend no more than one million euros, and candidates no more than a few thousand euros.13

In the end, in relation to the number of registered voters, spending for legislative elections is higher in France (a system combining regulated expenditure with public funding) than it is in the United Kingdom (where spending is capped but borne entirely by candidates and parties). In 1993, for instance, 2.80 euros were spent in France per citizen on the electoral register, whereas the comparable figure for the United Kingdom was 0.46 euros (Figure 3). The difference is partly due to the fact that the number of candidates in each constituency tends to be higher in France than in the United Kingdom, mainly because of the system of two-round voting.14 But the main reason for the difference is the stricter regulation in the United Kingdom.15

Figure 3. Aggregated spending of all candidates per registered elector, French and UK legislative elections, 1992–2015

If the aggregated spending of all candidates in French legislative elections (107 million euros) in 1993 is divided by the number of citizens on electoral registers (37.9 million), the spending per registered citizen comes to 2.80 euros. The corresponding figure for the 1992 parliamentary elections in the UK was 0.46 euros.

Given that there is no limit to the donations that parties or candidates can receive in the United Kingdom—and, as we shall see, private enterprise does not hold back from great generosity—everything suggests that if there were no cap on election spending it would be much higher there than in France. In any case, because of its one-legged system of regulation, it would seem that British parties have the means to spend much more than they do at present. This also raises questions about the motivation of donors.

If we combine the lessons of these different experiences, what can we ultimately conclude about campaign spending in these “regulated” democracies? First, it does not exceed a few euros per registered voter. One might even be tempted to say that the level of spending is rather low—and that is the argument regularly used by all who refuse to accept that in a country like France, money in politics as it exists today could weaken the very foundation of the democratic process: one person, one vote. Anyway, as we shall see in Chapter 8, even these relatively low amounts are enough to swing a considerable number of votes. According to my estimates, during the 2017 legislative elections in France, 40 million euros (barely 0.002 percent of French GDP) would have been enough to swing 30 percent of votes and to redraw the electoral map.16 In other words, without a spending cap, a few billionaires could easily “buy themselves” an election result. Another way of approaching the subject is to look at what happens in countries where such a cap does not exist.

But If Everything Is Permitted, Is Nothing Forbidden?

Political Parties Matter

To begin with, let me emphasize that if democracy is first of all about elections, it is also about political parties. This may sound obvious to some and yet it deserves emphasis. While trust in political parties tends to be even lower than trust in government,17 it is important to remember that effective democratic deliberation and decision-making cannot take place without collective organizations like political parties. Of course, I do not mean here that political parties as they exist today are perfect institutions that do not deserve some of the mistrust they face. Parties need to be reformed, restructured—and most often democratized; they need to innovate so as to engage better with citizens, recruit young members, and nominate working-class candidates. They also need to rethink their funding.

We should not give up on political parties; they are essential to an effective democracy, as was already stressed by Maurice Duverger in his seminal work of 1951.18 Or to put it another way, I strongly disagree with the opening sentence of Peter Mair’s recent book: “the age of party democracy has passed.”19 Mair might be right in his perception of a crisis of Western democracy and in his insistence that parties are increasingly failing to engage ordinary citizens.20 But there is no alternative. And, in fact, Mair fails to offer any.

It is hard to think of representation without political parties. I shall return in Chapter 9 to permanent and direct democracy and discuss popular referenda in particular. In principle, referenda can allow voters to participate in democratic decision-making without the intermediation of political parties, and this can sometimes play a very useful role. As we will see, however, direct democracy and referenda also raise serious issues about campaign funding and often require various forms of political organization to raise voters’ awareness and to develop the public conversation. Above all, most laws, state budgets, and public policies and regulations require extensive parliamentary deliberation and amendment-making processes before final adoption. Political parties play an essential role in organizing parliamentary elections and deliberation.

Of course, some argue that “technocracy”—the reign of experts and technicians—could work better than a combination of political parties and democracy and that in general we should prefer “objective” nonpartisan experts to elected politicians. In an influential article, Alan Blinder, for example, argues that “the real source of the current estrangement between Americans and their politicians is … the feeling that the process of governing has become too political.”21 Drawing from the example of central bank independence, he proposes to extend the model to other arenas such as tax policy. However, contrary to what he claims, the optimal tax rate on capital gains is not a purely technical but a highly political issue. Representative government requires political parties to aggregate information and preferences from diverse electorates about the likely consequences of policy decisions.

It is also worth stressing that one-party or hegemonic-party political systems—where elections take place without alternation in power—cannot be considered as democratic. For those who doubt it, John H. Aldrich and John D. Griffin have provided a brilliant demonstration in their study of political change in the American South.22 The South is of particular interest because there have been a few times when there has been a competitive party system, and many times when there has not, especially in the Jim Crow era, when the Democratic Party operated in effect as the hegemonic party.23 Aldrich and Griffin show that democracy has failed there in periods without real electoral competition, and that the emergence of a competitive party system in the 1970s and 1980s was associated with better political and social outcomes for the general public. When the South was far from having a fully developed two-party system, central characteristics associated with a well-functioning democracy were missing in comparison with the North. In particular, Southern members of both the House of Representatives and the Senate were far less responsive, and often fully unresponsive, to their citizens’ preferences. But almost as soon as a fully developed two-party system emerged in the South, the degree of elite responsiveness looked just like that found in the North.

Of course, the functioning of political parties varies from country to country, or between a US-style two-party system and a multiparty democracy such as those in France or Italy. In 1911, the political scientist Robert Michels described in his seminal work what he viewed as the iron law of political parties: oligarchic and bureaucratic elites tend to take control of them and to forget the social classes they are supposed to represent.24 Michels’s attitude to the Social Democratic Party in his native Germany also reminds us that a disillusionment with party politics is as old as electoral democracy itself.25 In 1961, while praising Michels’s theory of political parties as an imperfect form of collective organization, US political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset argued that different organizational forms (such as open primaries to select candidates in the US context) can make parties more responsive to popular demand.26

I shall later investigate campaign finance in European democracies and Canada, along with the United States. I start from the assumption that a properly functioning democracy requires careful consideration of the functioning and funding of political parties. One of my key proposals, for Democratic Equality Vouchers (DEV), would allow voters to exercise a degree of control and to contribute to the renewal of political parties, not only at election time but also on a year-by-year basis. But first we need to look more closely at the private funding of parties in all Western democracies.

No Limits, German Style

Let us begin with a perhaps unexpected case: Germany. France’s neighbor across the Rhine offers an interesting and paradoxical example of a country that developed quite early an innovative and sophisticated system of public funding of political parties (and even of political foundations intended to inform public debate), but that has been unable, or unwilling, to limit private donations, especially from big business. In practice, this concerns donations mainly from the export sector, which may affect party policies on trade surpluses or on regulation of the auto industry through such measures as a ban on diesel.

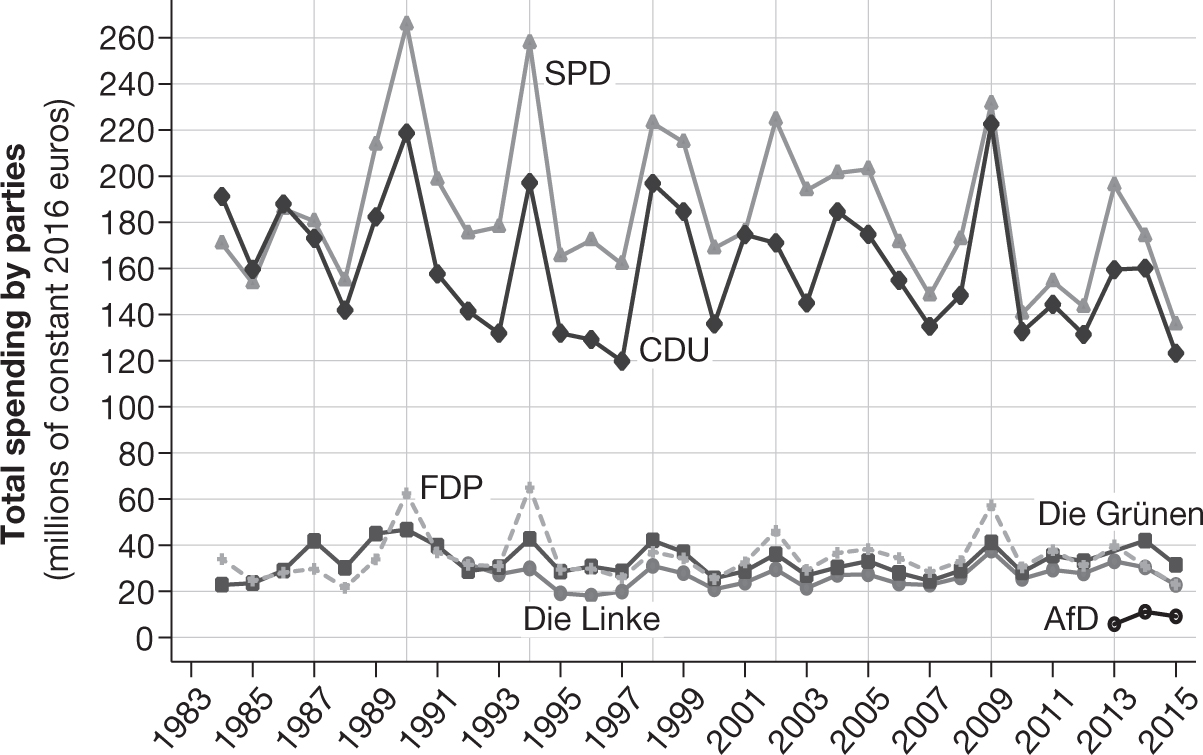

Figure 4. Total spending by the main political parties, Germany, 1984–2015

In 2015, the SPD spent 135.6 million euros. The vertical bars indicate the years of legislative elections in Germany, 1984–2015.

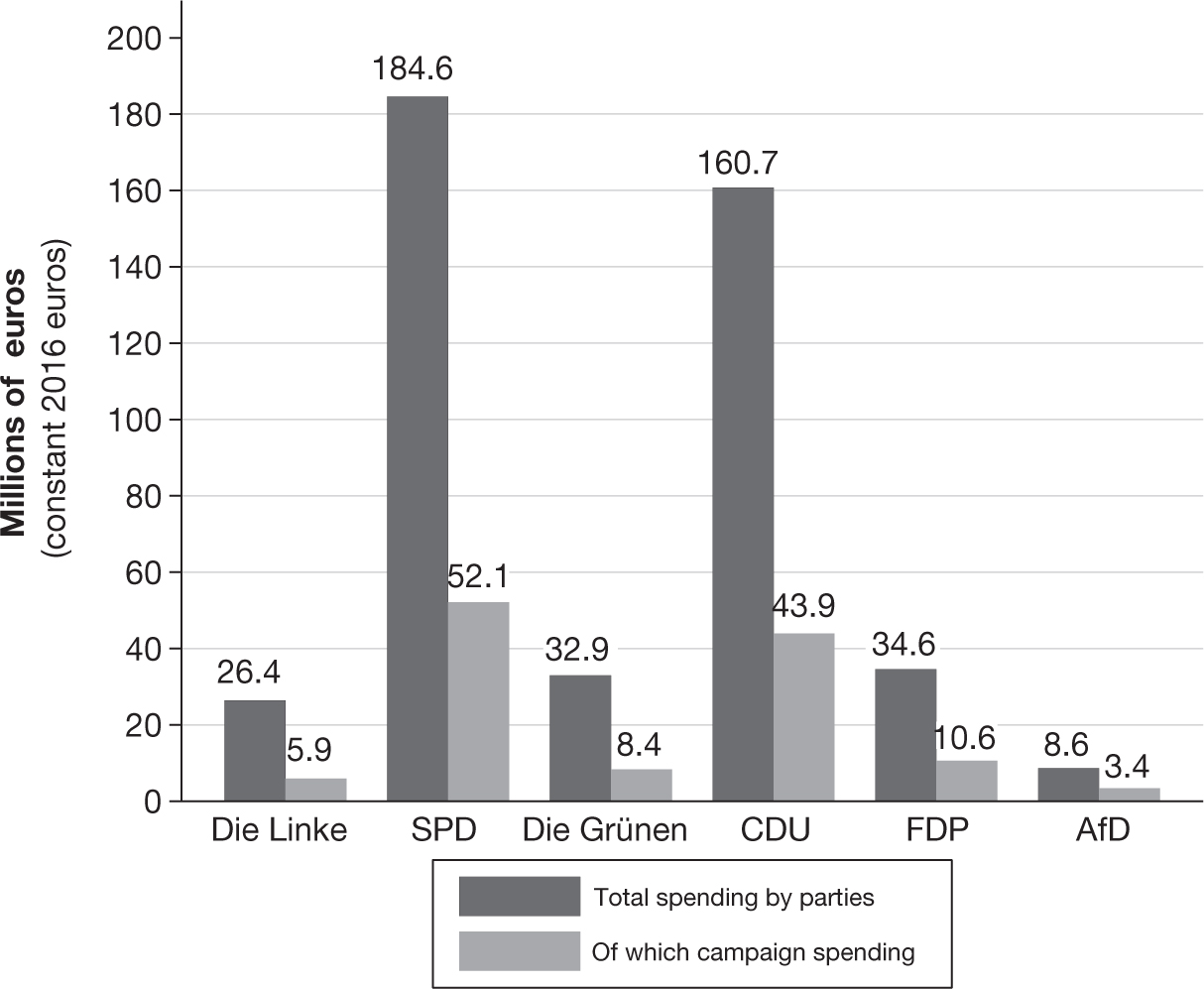

Figure 5. Total annual spending by the main political parties, including campaign spending for elections, Germany (annual averages calculated for the 1984–2015 period)

In the 1984–2015 period, the SPD spent an annual average of 184.6 million euros, of which 52.1 million euros went to election campaigns.

In Germany, campaign spending by candidates and parties is not capped, any more than is the amount of donations that parties can receive. What is the effect of this on the costs of democracy? I shall concentrate here on the main German parties, from left to right: Die Linke (the post-Communist party), the Social Democratic Party (SPD), Die Grünen (the Greens), the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the Free Democratic Party (FDP), and Alternative for Germany (AfD), the recently formed party of the German Far Right.27 During the period from 1984 to 2015, each of these parties spent an average of more than 80 million euros a year, or 1.40 euros per adult German citizen (Figure 4).

We should distinguish the two main parties, the SPD and CDU, whose average annual spending for the period came very close to 173 million euros (or three euros per adult head of the population), from the “small” parties, which spent a little under 32 million euros a year. The AfD is a newcomer: its expenditure was low in 2015, but this will increase in the coming years because the party’s high score in September 2017 (12.6 percent of the vote) will give it considerable access to public funding.

If we add up the spending of the five main parties, we find that an average of 476 million euros (or 7.87 euros per adult) was spent annually by the political parties in Germany over the past thirty years. Campaign spending represented a significant proportion of this—28 percent on average. Thus, out of the 184.6 million euros that the SPD spent in an average year, 51.2 million corresponded to campaign spending (Figure 5).

A Revealing International Comparison

The difference between Germany and both the United Kingdom and France—where spending is limited by law, especially in election periods—is striking on both the left and the right, particularly with regard to total annual spending. On average, the SPD spent 2.6 times more per annum than the French Socialist Party (PS) during the 2012–2016 period, and the difference was the same between the CDU and the French Républicains (Figure 6).28 Nor is this pattern peculiar to the “large” parties, since the German Greens spent an annual average of 35.5 million euros during this period, or four times more than the French Greens (8.8 million euros).

Of course, Germany has a larger population than France, but this is by no means sufficient to explain the differences in spending. Per head of the adult population, the SPD’s annual average spending during these years (2.40 euros) was twice as high as that of its French counterpart.

It should be noted that, relative to population size, the spending of Spanish parties is also very large, but that, as we shall see in Chapter 3, they receive comparatively little from private donations; the explanation for this is the generous public funding of political parties introduced in 1985. Thus, Spanish parties are among the biggest spenders per head of the adult population (just after Germany), and this is true even on the right (the Partido Popular spends even more than the CDU). Of course, this includes election spending partly reimbursed by the state, which may distort the comparisons if we are not careful. In France, for instance, the fact that campaigns are candidate-led rather than party-led artificially reduces the spending costs borne by parties. What, then, is the picture in Spain if we separate out election spending? In 2015, the Spanish Socialist Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) spent 87 million euros, of which roughly 30 percent (25 million) consisted of election expenses almost fully reimbursed by the state. All in all, apart from election expenditure, the average annual spending of the PSOE came to 61.8 million euros for the 2012–2016 period, or 1.66 euros per adult head of the population (much higher than the 1.20 euros of the French Socialist Party). Similarly, the nonelection spending of the Partido Popular averaged 60.8 million euros, or 1.80 euros per adult, whereas that of the Republicans in France did not average as much as 1.10 euros per annum during the period.

Figure 6. Annual spending by the main political parties (Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Belgium, and the United Kingdom), annual averages 2012–2016

In sum, the rules governing relations between money and politics display a large difference between countries. What consequences does this have? To what extent are the divergent spending structures reflected in election campaigns, the election results of various parties, the renewal of political personnel, the emergence of new movements, and the public policies of governments? To answer these critically important questions, we first need to have a better idea of where the money comes from: public funding or private “generosity”? Clearly, the implications vary depending on the answer.

Public Funding, Private Funding

Elections cost a lot. Or rather, a number of Western democracies have chosen to allocate large, sometimes huge, sums of money to them. The differences among countries reflect their regulations governing the amount that candidates are permitted to spend; we have briefly indicated the situation in a selection of countries. But they also reflect different regulations governing what individuals and / or companies are permitted to donate. The next two chapters will focus on the private funding of democracy and examine in detail various national models. We shall see that the amounts and the players in question differ fundamentally from country to country. In Germany, the automaker Daimler gives each year with its left hand 100,000 euros to the SPD, and with its right hand the same sum to the CDU. Of course, this has nothing to do with Daimler’s wish to avoid at all costs a legal ban on diesel in cities—heaven forbid! In France, companies are no longer permitted to donate to political parties; but when they were, a company such as Bouygues did not hesitate to show great liberality in its use of checkbooks, caring little about the political colors of recipients. Fifty shades of generosity.

National differences in the size of party spending ultimately reflect different ways of publicly funding democracy. We have seen, for example, that British political parties spend much less on average each year than their German counterparts. But this does not mean they are less captive to private interests—on the contrary. The Conservative Party receives annually more than 25 million euros in private donations, or 5 million more than the CDU in Germany (not in itself cause for complaint). But this simply indicates that the United Kingdom does not have a system for the public funding of political parties, whereas German parties receive, in addition to private donations, a generous public subsidy dependent on their past election successes.

In other words, a government that wishes to influence the direction of politics by means of private money and the injection of public funds has several weapons at its disposal. Let us now look at these in order, so that we can eventually give answers to the following questions. How much does the state spend each year to fund the political preferences of its citizens, and to what extent does the amount vary with their income? In countries where there is little regulation, does the massive injection of private money render public subsidies ineffectual? What are the actual consequences of the various models of funding? Do what we might call “market models” favor more conservative parties over movements more inclined to social protest? Do such models lead to unequal representation of people’s political preferences and to skewed public policies? These questions urgently require answers, because in a number of countries today the public funding of democracy is under threat. In some cases it has already been abolished, with often dramatic consequences that include the development of self-perpetuating inequalities.

The aim of this book is to make readers more aware of current practices and to give them all the cards they need to choose the model most likely to restore the health of democratic systems. The key question is what reforms must be made without delay to curb the role of private money in our democracies—and to reestablish the fundamental principle of “one person, one vote.” But please be patient: that will be addressed in Part Three.