8 Building Elite Eating Habits

![]()

WITHIN THE PAST TWENTY YEARS, PSYCHOLOGISTS AND NEUROSCIENTISTS have learned a lot about how habits and habit change work. Recent discoveries help clarify why some people succeed in changing habits—including diet habits—and others fail. Scientists now recognize that three special factors contribute to successful habit change. I like to call them the power of reward, the conformity factor, and the principle of minimal disruption. Although elite endurance athletes are no more likely than others are to be well versed in the latest science of habits, they nevertheless exploit all three of these factors to make the habits of the Endurance Diet stick—and so can you.

The Merriam-Webster Medical Dictionary defines a habit as “an acquired mode of behavior that has become nearly or completely involuntary.” Habits can be as subtle and meaningless as picking at one’s eyebrows while thinking (something I do) and as complex and important as performing heart bypass surgery with exactly the same procedure each time. We all know that habits are a big part of life, but we seldom appreciate just how big. It has been estimated that 40 percent of the actions the average person performs each day are habitual rather than products of a conscious decision.

The human brain is designed to form habits. It tries to turn everything we do more than once into a habit. The reason it does so is that habits foster both efficiency and proficiency. The first time you perform any novel action or behavior, you have to concentrate very hard on what you’re doing. But the more you repeat it (the more habitual it becomes), the less active your brain is required to be in its performance. This process frees up your conscious mind to attend to other things. Without the ability to form habits, we would be extremely limited in terms of the number and variety of skills we could acquire.

A habit has three components: a trigger, a routine, and a reward. The routine is the behavior that constitutes the habit. Workouts, for example, are habits for endurance athletes. A trigger is a cue that causes a person to repeat a habitual behavior. An alarm clock sounding at 5:00 a.m. is the trigger that causes many swimmers and triathletes to drive to the local pool for a masters swim class. A reward is just that: some benefit that the habit confers, such as the feeling of accomplishment that comes with completing a workout.

The reason habits are hard to change is that they rewire the brain. Once a certain behavior has become habitual, its trigger compels us to repeat it, often unconsciously. At the same time, anticipation of the habit’s reward creates a craving for it that is difficult to resist. A kind of psychological inertia develops, reinforcing the habit.

The neural imprint of each habit, eating habits not excepted, is essentially permanent. Once a behavior has been bundled together in the brain with a trigger and a reward, these three components of habit remain linked. This does not mean that habits cannot be broken, however. It just means that even after a habit has been broken, it remains latent inside the brain. This has been demonstrated in studies in which rats are taught one habit and then a second, contradictory habit in an effort to erase the first one. When these rats are reintroduced to the situation in which the original habit was learned, they don’t have to learn it again from scratch but are able to revert to it right away. Other studies have shown that humans who have broken a certain habit are likely to revert to it under stress, again because its neural imprint is still present in the brain.

Eating is a special habit because it is an absolute necessity for life. Infants come into the world with built-in eating triggers (mainly the symptoms of physical hunger) and the act is intrinsically rewarding, offering the pleasures of taste and satiety. These biological exigencies ensure that everyone is in the habit of eating. Of course, individual persons have distinct eating habits. There is tremendous variety in what, when, where, and how people eat. But each person’s eating patterns tend to be consistent. In other words, everyone’s eating patterns are equally habitual. Like other habits, therefore, they exert an inertial force, resisting efforts to change them. Even so, people succeed every day in improving their eating habits. Understanding how they do will help you make a successful and lasting transition to the Endurance Diet.

The Power of Reward

We persist in our habits largely because we expect to be rewarded by them. Both parts of this formulation—expectation and reward—are important. What makes it so difficult for many of us to change our dietary habits is that, to a certain extent, this type of change entails shifting from a reward that is intrinsic to eating—the pleasure of low-quality foods—to a reward that is extrinsic to eating—better health, fitness, appearance, quality of life, and/or self-esteem.

The advantage that elite endurance athletes have in this regard is that they are more richly rewarded for improving their health and fitness than just about anyone else. Most elite athletes enjoy training more than they enjoy eating healthy. In other words, they are more intrinsically rewarded by working out than they are by maintaining their dietary standards. Nevertheless, they are just as disciplined in their eating as they are in their training because they know that healthy eating is as critical as training is to attaining the extrinsic rewards of money, fame, and the thrill of winning. Such rewards are out of reach for the vast majority of us, and that may be part of the reason our attempts to improve our diets more often fail.

This doesn’t mean that, as a recreational endurance athlete, you cannot exploit the power of reward to find success with the Endurance Diet. The rewards of getting fitter and achieving goals are equally available to all endurance athletes. As the optimal diet for endurance fitness, the Endurance Diet yields these rewards in greater measure than other ways of eating do. What’s more, the Endurance Diet can become habitual even before these rewards are experienced if you truly believe it is the optimal diet for endurance fitness and expect these rewards to come.

We touched on the power of expectations in Chapter 7. The importance of expectation as it relates to habit change cannot be overstated. Psychology research has proven that if you expect to succeed in building new habits, including diet habits, you are more likely to succeed. One example is a 2005 study done by doctors at the University of Minnesota. More than three hundred adults who had enrolled in a weight-loss program based on habit change were asked to rate their own chances of achieving their weight-loss goal. When the program ended eighteen months later, participants who expected to lose more weight were found to have shed the greatest number of pounds.

Expectations of success can come from a variety of sources. One is self-efficacy, or belief in your own ability to achieve a particular reward through habit change. Another is confidence in the method or program of habit change that you are using to pursue a reward. The more faith you have in the method or program you’ve chosen, the more likely you are to reap its rewards. But faith in a diet cannot be manufactured out of thin air. We all need substantive reasons to believe it will work.

Elite athletes commit to the Endurance Diet because they believe in it—they have a high degree of confidence that it will yield the extrinsic rewards they seek to gain from it. And they believe in the Endurance Diet because they see what it has already done for other elite athletes. When a rising young elite endurance athlete looks around and sees that all of the top performers around him eat everything, eat quality, eat carb-centered, eat enough, and eat individually, it’s natural for him to expect that he will benefit similarly from the same habits. A major objective of this book is to give you a vicarious version of this experience and thereby instill in you a similar expectation of success.

Obviously, believing in the Endurance Diet won’t carry you very far if it doesn’t work. But it really is the optimal diet for endurance fitness—and as such, it inevitably produces the expected rewards. These rewards complete the habit loop, creating a “craving” that impels you to persist in the five habits. When you get to this point, you’re home free, because practicing the habits no longer requires effort. It is automatic, something you want to do.

What’s more, there is evidence that healthy eating habits become more intrinsically rewarding after they have been sustained for a while. This means the longer you stay on the Endurance Diet, the less you will crave low-quality foods and the more you will enjoy and crave high-quality foods. A 2014 study led by Susan Roberts of Tufts University found that after six months on a healthy diet program, initially overweight individuals exhibited reduced activity in brain areas associated with craving when shown images of low-quality “calorie bombs” and heightened activity in the same areas when shown images of healthy foods of the kinds they were eating regularly on the diet (on which the subjects had lost 14.1 pounds on average). They were now as tempted by strawberries as they were by potato chips!

The Conformity Factor

Habits of all kinds, including food-related habits, are contagious. People tend to adopt the eating behaviors that are most pervasive in their social environment. Proof of this comes from a 2013 study conducted at Utrecht University in The Netherlands. Each participant was invited to choose a healthy snack or an unhealthy snack from a pair of displays. Empty wrappers were left near each display as evidence of choices made by previous participants. Sometimes the researchers left more empty wrappers near the healthy snack display; other times they left more near the unhealthy snack display. Subjects were found to be much more likely to choose the type of snack that appeared to have been chosen more often by those who came before.

These findings were reinforced by the results of a similar study done in the same year by scientists at the University of Birmingham. In this study, each subject ate a cafeteria meal with a partner who, unbeknownst to him or her, was working for the researchers. Sometimes the dining partner chose healthy foods, other times unhealthy foods. Again, the subjects exhibited a pattern of conformity in their food selections.

The good news we glean from these studies is that healthy eating habits are as contagious as unhealthy ones. The infectiousness of healthy eating habits works to the advantage of elite endurance athletes, who inhabit an environment where the five habits of the Endurance Diet are practiced almost universally. Being surrounded by men and women who eat everything, eat quality, eat carb-centered, eat enough, and eat individually makes it easy for each athlete to do the same. On the flipside, it makes it hard to do otherwise.

When I was in Spain with the LottoNL-Jumbo cycling team, I asked Marcel Hesseling, the team’s nutritionist, what he would say to a team member who came back to the athletes’ table at the Sala Oriente from the hotel buffet carrying a plate laden with French fries and pastries.

“I wouldn’t say anything,” he said. “I wouldn’t have to.”

What Hesseling meant was that the rider would feel so much tacit peer pressure from seeing the healthy plates of his surrounding teammates that he would never repeat his mistake. Indeed, the human propensity to conform to the dominant eating patterns in any given environment is so strong that no member of the LottoNL-Jumbo team or any other World Tour cycling team would dare to eat a plate of fried potatoes and cake in front of his teammates in the first place.

Most recreational endurance athletes and exercisers do not have the good fortune to eat routinely in the company of people who eat in the best possible way for endurance fitness. This disadvantage makes it somewhat harder for recreational athletes and exercisers to exploit the conformity factor. But there are things you can do to make dietary conformity work for you. One is to rally your family around the healthy habits you wish to sustain. Another is to share meals, recipes, and tips with training partners and other friends whom you regard as positive dietary influences. You can also use social media to your advantage, for example, by joining a Facebook group of like-minded eaters.

The Principle of Minimal Disruption

The principle of minimal disruption is the idea that, when changing a habit, you should change it as little as necessary in order to achieve the desired result. The reason is that it is easier to make small habit changes than it is to make drastic ones. This doesn’t mean smokers are better off reducing their habit from one pack a day to half a pack instead of quitting completely. If a smoker’s goal is to break the addiction, he or she cannot achieve it by merely smoking less. However, the person can still take advantage of the principle of minimal disruption by inserting a new behavior between an existing trigger and an existing reward.

In The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg tells the story of a smoker who kicked the habit in precisely this way. He recognized that a feeling of restlessness was his trigger for lighting up and that a feeling of relaxation was one of its rewards. After trying a few different things, he settled on meditation as an alternative to smoking. Like smoking, meditation relaxed him, so it did not take him long to develop a craving to meditate rather than to smoke when he felt restless.

Changing eating habits is definitely different from giving up smoking, but not so drastically different. As I mentioned earlier, what makes it so hard for many people to change their dietary habits is that it entails shifting from a reward that is intrinsic to eating (pleasure) to a reward that is extrinsic to it (fitness). Many low-quality foods are more pleasurable to eat compared to most high-quality foods. Studies have even shown that processed calorie bombs alter brain chemistry in ways that enhance cravings for them, making them even harder to give up.

There is disagreement among scientists as to whether particular foods, or whether eating in general, is ever truly addictive in the same sense that drugs like nicotine are, but in any case the solution is the same. As with smoking, people are more likely to succeed in changing their eating habits if instead of simply saying “no” to their existing habits they say “yes” to alternative habits that address the same trigger (a craving for pleasurable food) and offer the same intrinsic reward (pleasure) but do so in a way that yields the extrinsic reward of fitness.

In addition to yielding better fitness than other diets, the Endurance Diet offers more intrinsic satisfaction than most popular diets because it is not drastically different from the way people naturally like to eat. In other words, it is less disruptive to normal ways of eating.

Most people—especially people with unhealthy diets—are comfortable with their current eating habits; they just don’t like the results they’re getting from them. Dietary change should aim to improve the results without sacrificing the comfort. The way to do this is to continue to eat as familiarly as possible while making changes that are sufficient to produce the desired results. The Endurance Diet allows and even encourages this.

If you look at what’s on the breakfast, lunch, or dinner plate of an elite endurance athlete, as we have done throughout this book, you won’t see anything that stands out as unusual or extreme except the overall quality of the food combinations. Switching from a merely average diet to the Endurance Diet is less disruptive, requiring less change, than shifting to the various popular diets that recreational endurance athletes often go for.

There is an inverse relationship between how abnormal a diet is and how long its average follower is able to stay on it. One of the most extreme diets is the raw food diet. A prominent apostate of this way of eating has estimated that 99 percent of people who try an all-raw diet eventually give it up. By contrast, elite athletes who adopt the Endurance Diet almost never quit.

Each of the five key habits contributes to the sustainability of the Endurance Diet as a whole. Eating everything is a natural human predilection. Eating quality creates a craving for quality, as was shown in the study by Susan Roberts described earlier. Eating carb-centered feels comfortable because most traditional cultural cuisines are carb-centered. Eating enough requires no more willpower than mindless overeating because it is not a denial of hunger (as in eating restraint) but an embrace of true physical hunger as the basis for decisions about when and how much to eat.

Eating individually contributes to the sustainability of the Endurance Diet in a different way. Although the first four habits make the diet generally comfortable for all athletes, the fifth habit makes the transition to it smooth and easy for each athlete separately. Eating individually is all about creating a personalized version of the diet that is based on a single athlete’s needs and preferences.

When elite athletes transition to the diet, they do not toss out all of their existing dietary practices and replace them with a completely new set of practices borrowed from someone else. Instead they change as little as necessary to bring their diet up to Endurance Diet standards, retaining all of the familiar practices that are consistent with its requirements. In so doing, they exploit the principle of minimal disruption to activate the power of reward and the conformity factor. An improved diet is more rewarding when it retains features of a prior diet that, though needing improvement, was at least enjoyable. An improved diet is also easier to stick with when it does not unnecessarily abandon some of the cultural and familial traditions that the previous diet conformed to.

The American pro cyclist Larry Warbasse offers an interesting example of how elite endurance athletes use the principle of minimal disruption to ingrain the five key habits. A Michigan native with a Lebanese mother who loves to cook, Warbasse was raised on a healthy diet consisting largely of traditional Middle Eastern foods (lamb, pita bread, etc.). He did not live in a dietetic bubble, however. The family went out for fast food occasionally and Warbasse ate as much ice cream as the next American kid.

When he began to compete in Europe in his late teens, Warbasse learned about the importance of diet for fitness and performance and embarked on a period of experimentation that eventually brought him to the same place it leads every other elite endurance athlete. “I have found that a simple, healthy, nonrestrictive diet (eat junk occasionally if you want it, don’t worry about whether something has gluten in it, don’t worry about lactose, etc.), works the best for me,” he told me via e-mail from his home in Nice, France.

Warbasse’s preferred breakfast is oatmeal with coconut milk, honey, a fried egg and two egg whites, and a mug of coffee. His favorite lunch is basmati rice and an omelet with two eggs and two egg whites. He snacks on Greek yogurt, apples, and berries. A typical dinner comprises a salad of spinach and arugula, cherry tomatoes, green peppers, and an olive oil–based dressing; fish, chicken, turkey or (once or twice a week) beef; and one of the following starches: sweet potato, spelt pasta, buckwheat, or rice.

Warbasse practices all five Endurance Diet habits. The typical day’s menu just described covers all six high-quality food types. Warbasse eats few low-quality foods except during the short off-season, but, he told me, “If I really want something, I will have it.” His breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks are carbohydrate-centered. He also eats mindfully, eschewing eating restraint, because, as he put it, “I would rather eat too much and gain a bit of weight than be depleted and cracked.” And he eats in ways that satisfy his individual needs, for example, by liberally salting his food to make up for the exceptionally large amounts of sodium he loses in sweat.

What is somewhat unusual about Warbasse is that, unlike most elite athletes, he did experiment with more extreme dietary measures before settling on the same five habits that work best for everyone. “I have tried avoiding all sorts of food in the past: gluten, milk, added sugar, high fructose corn syrup, etc.,” he explained. “I really found that the more you avoid something, the more you want it. So now there isn’t really much of anything I avoid; I just try to eat a simple, healthy diet.” A diet that, importantly, is not so different from the one he enjoyed while growing up.

Warbasse discovered in a roundabout way that adhering to the principle of minimal disruption was the best way to develop habits that he could sustain consistently and indefinitely.

The Perfect Day

The five habits of the Endurance Diet are daily habits. To practice the habit of eating everything is to eat all six high-quality food types each day. To practice the habit of eating quality is to attain a high Diet Quality Score each day. To practice the habit of eating carb-centered is to eat carb-centered meals and snacks not once in a while but every day. To practice the habit of eating enough is to eat meals that are sized and timed in such a way that one is physically hungry when each meal starts and comfortably satisfied when the meal ends. To eat individually is to practice the first four daily habits in ways that meet individual needs and preferences.

If you can practice the Endurance Diet for just one day, you can practice it every day. Adopting the habits may seem daunting if you think of it as a matter of obeying a set of general rules for the rest of your life. But it won’t seem daunting at all if you think of it as a matter of coming up with a workable daily eating routine that you simply repeat each day. Of course, this does not mean that you should eat exactly the same way every single day. But mapping out a single, optimal day’s eating for yourself is a great way to get started. I call this exercise “the Perfect Day.”

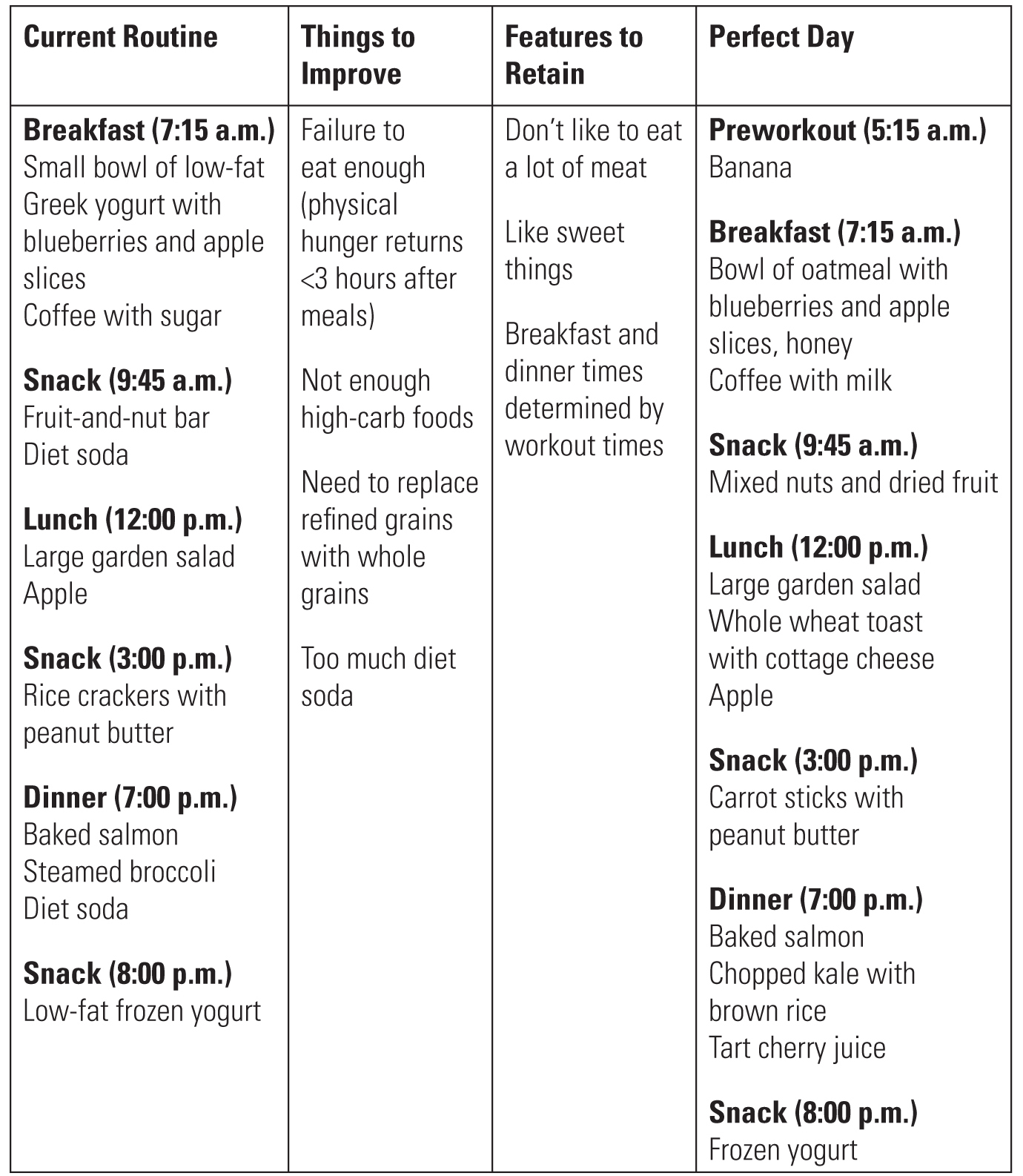

To begin the exercise, create a table with four columns, as in Table 8.1 (or use the blank table in Appendix A). The first column will be used to document your current routine. (Remember, adopting the Endurance Diet is not about replacing your current diet but evolving it.) Use this space to write down when and what you ate yesterday or, alternatively, when and what you eat in a typical day. Be fully honest and inclusive. If you spontaneously ate a handful of crackers yesterday afternoon when you opened up the pantry to look for something else, record it. We like to think of such behaviors as exceptions to our routine, but in almost every instance they are part of it. Include in this food journal some information about amounts, but don’t be too fussy. For example, if you drank a glass of mango juice, write down “glass of mango juice” rather than “8.5 oz. mango juice.”

When you’ve got everything written down, move to the next column and make a list of the ways in which your current routine falls short of Endurance Diet standards. This list should be fairly easy to compile, though it may require some review of the previous chapters. For example, if your current diet includes no nuts, seeds, and healthy oils (failure to eat everything), note this. If your current diet includes more refined grains than whole grains (an opportunity to increase diet quality), write it down.

Now move to the third column and make a separate list of features of your diet that do not defy the five habits and that you’d like to (or must) retain as you move forward. This list may require a little more thought. If there are any specific high-quality foods that you want to continue to eat regularly—such as eggs for breakfast—add this feature to your list. Even if there are one or two low-quality foods—perhaps a second glass of wine after dinner—that you strongly prefer to afford a small place in your Perfect Day, add these as well.

Beyond specific foods, the list of current features of your diet that you wish to retain may also include such things as a preference to buy lunch on workdays at a great little deli located near your office, the need to stay within a very limited weekly food shopping budget, and a preference to cook dinners from scratch only on weekends. The Endurance Diet can be molded to work with most constraints, and you can always revisit them later if they become roadblocks to further progress in your health and fitness.

The fourth and last column is your Perfect Day. Here you will write out a specific one-day eating plan that evolves your current routine, as detailed in column one, by modifying it according to the information in column two and retaining the features in column three. This plan should include an approximate time for each meal and snack. Note that these times, as well as the number of snacks you eat and the amount of food you eat in each meal and snack, may need to be adjusted based on the results of the physical hunger experiment described in Chapter 6. For this reason, you may wish to complete that experiment before you create your Perfect Day.

There will necessarily be some arbitrariness in your food selections. For example, of the ten or twelve things you regularly eat for dinner that fit the design of your Perfect Day, you must choose one. But bear in mind that doing so does not fate you to eat this one meal every night for as long as you live. The Perfect Day is just an exercise to get you started on the Endurance Diet. Nor do you have to get it just right the first time. If, for example, you sketch out a provisional Perfect Day and then realize you accidentally left out the dairy category, go back and add it (removing one or more other items to “make room,” if necessary).

As in column one, include basic information about food amounts but don’t try to be too precise. If you need to eat a large bowl of oatmeal in the morning to stave off the return of physical hunger until lunch (or until your midmorning snack), write down “large bowl of oatmeal” rather than locking yourself into, say, “1 1/4 cups oatmeal.” This information, alongside the schedule of meals, will set you up to successfully implement the habit of eating enough, but actually eating enough comes from listening to your body, not from executing a plan.

Use Table 8.1 to get a feel for the process, not as a blueprint for the actual content of your own Perfect Day. It does not come from an actual person but instead is based on a particular type of athlete I encounter often. Let’s call her Brenda. She is a serious age-group triathlete who works out twice a day most days—early in the morning before work and again after work. She is concerned about maintaining a very lean body composition, and she does this currently by eating lots of fruits and vegetables, avoiding fat and starches, and limiting her portion sizes. If asked to name the biggest flaw in her diet, Brenda would point to her sweet tooth, which in a typical day she indulges with two diet sodas and a serving of low-fat frozen yogurt.

Measuring Brenda’s diet against the standards of the Endurance Diet, however, reveals other flaws. The meals are too small for an athlete who trains as heavily as she does. The reason she snacks so frequently is that she becomes physically hungry well before lunchtime and dinnertime. To overcome this problem and find more energy for workouts, Brenda needs to let go of her eating restraint and start eating mindfully in order to eat enough. The specific energy source she is most lacking is nonsugar carbohydrate, so it makes sense for her to increase her meal sizes by adding whole-grain foods. Doing so will also raise her Diet Quality Score.

Brenda’s current DQS is +5, which would probably strike her as surprisingly low if she were a real person. Although the large number of fruits and vegetables in her day give her a lot of points, most of them are taken away by the addition of sugar to her coffee (which makes it a sweet or low-quality beverage); her fruit-and-nut bar, which also counts as a sweet because it contains added sugar; the two diet sodas (low-quality beverages); the rice crackers (refined grain); and the frozen yogurt. Many athletes of Brenda’s general type eat foods that aren’t as healthy as they seem.

Table 8.1 An Example of a Perfect Day

Brenda’s Perfect Day scores 25 DQS points. The big jump in quality is achieved by starting the day with a banana to fuel her morning workout, adding whole grains (and replacing refined grains), eliminating one can of diet soda and replacing the other with tart cherry juice, and upgrading her snacks. All of this can be done without leaving Brenda’s sweet tooth unsatisfied. There’s still plenty of fruit, the honey in her oatmeal gives her another little sweet fix and the tart cherry juice yet another, and she still gets to end her day with frozen yogurt, although the low-fat variety has been replaced with the less-processed kind made with whole milk. Brenda may even find that her sweet tooth is dulled somewhat by the extra calories she’s getting throughout the day.

The other items in Brenda’s “Features to Retain” column are also respected. She prefers to eat meat or seafood just once a day, and that’s plenty, so her Perfect Day includes no meat/seafood other than baked salmon for dinner. Brenda might have addressed her hunger issue partly by shifting the timing of her breakfast and dinner, but this wasn’t an option given her workout schedule, so the issue is addressed instead in her Perfect Day through increases in the size of her meals and the addition of a snack before her morning workout.

One Day at a Time

Once you have a Perfect Day you’re satisfied with, consider creating a second one. Some athletes need an alternative template for their personal Endurance Diet because there are two different types of days in their week. For example, a swimmer who travels frequently for business may need one Perfect Day for when she’s at home and another for when she’s on the road. A runner who is divorced may need one Perfect Day for when he has the kids (who are fussy eaters) and another for when his ex-wife has them. Many athletes need a different Perfect Day for the weekend than they do for weekdays.

Whether you create one Perfect Day or two, here are some simple ideas to keep in mind:

• Practice makes habit. Recognize that the purpose of the Perfect Day is not for it to be framed, hung on a wall, and admired. Its purpose is to be practiced. On the first day of your life on the Endurance Diet, try to apply your Perfect Day exactly as it is written. Pay special attention to your body’s hunger and satiety signals and make any adjustments needed to ensure that you begin to feel physically hungry shortly before mealtimes and finish meals feeling comfortably satisfied.

• Prioritize. Don’t feel ashamed of repeating your Perfect Day more or less exactly, day after day, in the beginning. Your top priority at this stage is to embed new habits, and the less day-to-day variation there is in your eating routine, the more quickly this process will move forward. In fact, there’s nothing wrong with continuing to eat pretty much the same things indefinitely if doing so helps you stay on track. The diets of many elite endurance athletes are quite repetitious, and are no less healthy for it. A majority of the athletes who shared information about their diets with me for this book eat the same breakfast every day, and elite athletes in less developed countries eat pretty much the same breakfast, lunch, and dinner every day.

• Mix it up. A varied diet is optimal, though. You can add variety to your diet with little effort by making modular substitutions to your Perfect Day, replacing one type of vegetable, fruit, nut, seed, healthy oil, whole grain, dairy food, meat, or seafood with another. Further variety can come from cycling through the endurance superfoods presented in Chapter 10 and the Endurance Diet recipes in Chapter 11, and also from healthy recipes found in other sources. You can approach this expansionary process in a systematic way by trying one new recipe per week and by choosing one superfood per week that you do not normally eat and adding it to your routine.

• Keep an eye on the big picture. Never allow yourself to be tied down to your Perfect Day. None of its details are important. What is important on the Endurance Diet is that you consistently eat everything, eat quality, eat carb-centered, eat enough, and eat individually. The Perfect Day is nothing more than a tool that will help you gain momentum with these habits so that practicing them becomes automatic, something you do naturally without much thought.

Finally, always remember, too, that the habit of eating individually entails allowing your diet to evolve as your needs and preferences change, as they are sure to do to some degree. Adopting the Endurance Diet is about replacing bad habits with good ones. Living the Endurance Diet is about growing in good habits.