Chapter 5

Me, I am going to Spain with the boys. I don’t know who the boys are, but I am going with them.

Martha Gellhorn (1937)

This chapter examines the role of women correspondents in the reporting of the Spanish Civil War.1 Such an analysis has, I believe, intrinsic historical value. Although labelled a civil war, it was a conflict that implicated all the major international powers of the day. But the Spanish Civil War was about more than power politics. From the outset, it was recognized as a battle of ideas, ideals and ideologies, which meant that issues of mediation and representation assumed crucial importance. As will be shown, any adequate analysis of the role of the international news media needs to consider the distinctive and significant contribution made by women correspondents. More broadly, I hope this case study makes a small contribution towards elaborating what James Curran (2002) identifies as ‘feminist narratives’ of media history, particularly as they apply to understanding the roots and evolution of foreign correspondence in general, and war reporting specifically. These domains have been dominated historically by men and, particularly with regard to the reporting of armed conflict, it is often claimed that they are infused by masculinist values. As Dafna Lemish (2005: 275) recently put it: ‘It is mostly men who perpetrate the violence, organise a violent response, and present media stories about it’.

Although it is difficult to dispute the general legitimacy of this observation, we need to be wary of overgeneralization. One can readily think of many striking contemporary exceptions to the proposition that war stories are male stories. For example, in the UK, there is the influential and prestigious presence of female journalists such as Orla Guerin, Maggie O’Kane and Kate Adie. Furthermore, there is a historical lineage to female foreign correspondence that can be traced back to the 1840s (see Sebba 1994). An important aspect of the recognition that ‘the media politics of gender deserve more attention than they have received to date’ (Carter et al. 1998: 3) is the development of an historically informed perspective that retains, and where necessary recovers, understanding of the past contributions, achievements and trials of women working in these male-dominated environments. Central to this project is the need to examine the extent to which these pioneering women introduced different values and perspectives from their male counterparts, and the reasons for these differences.

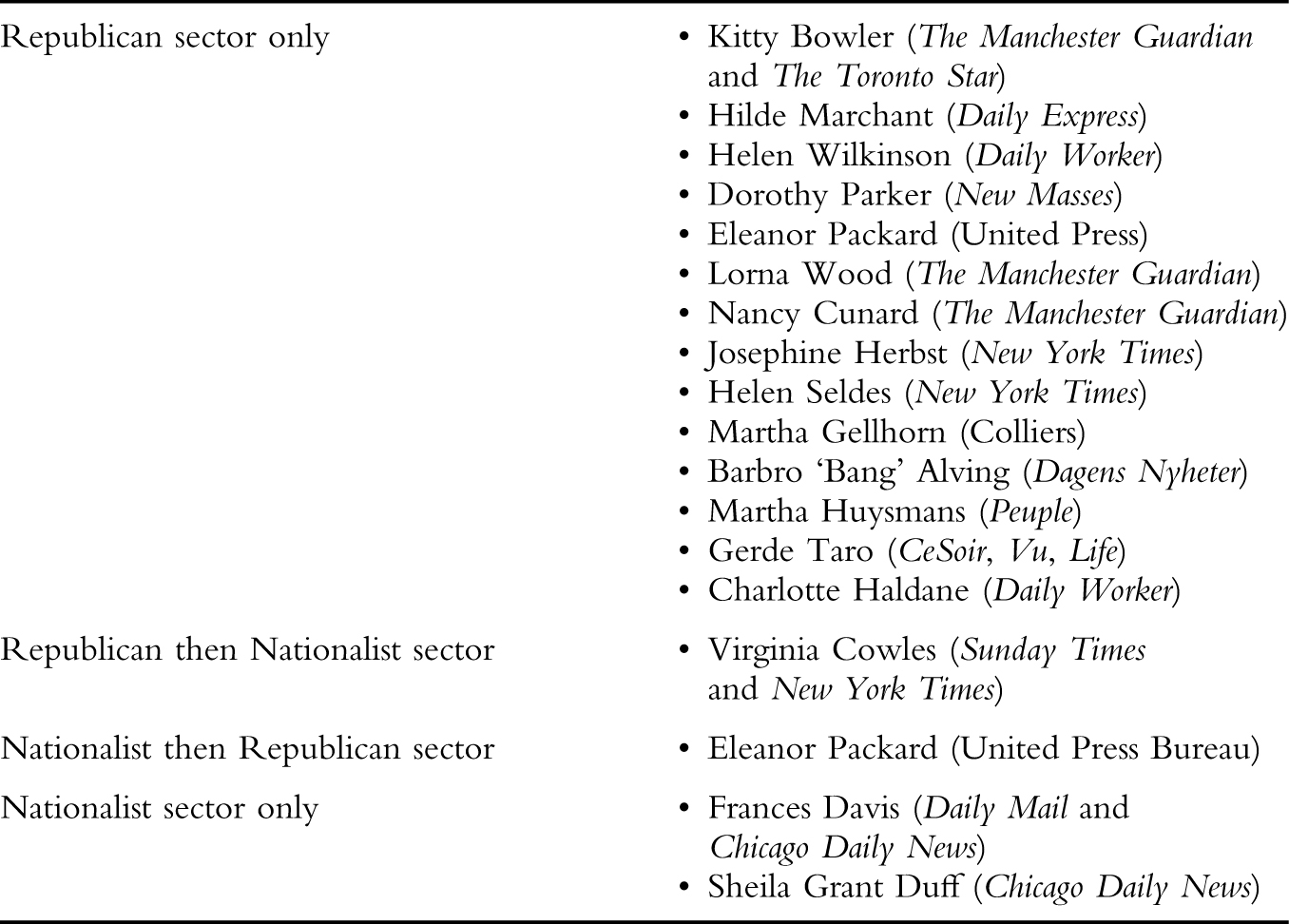

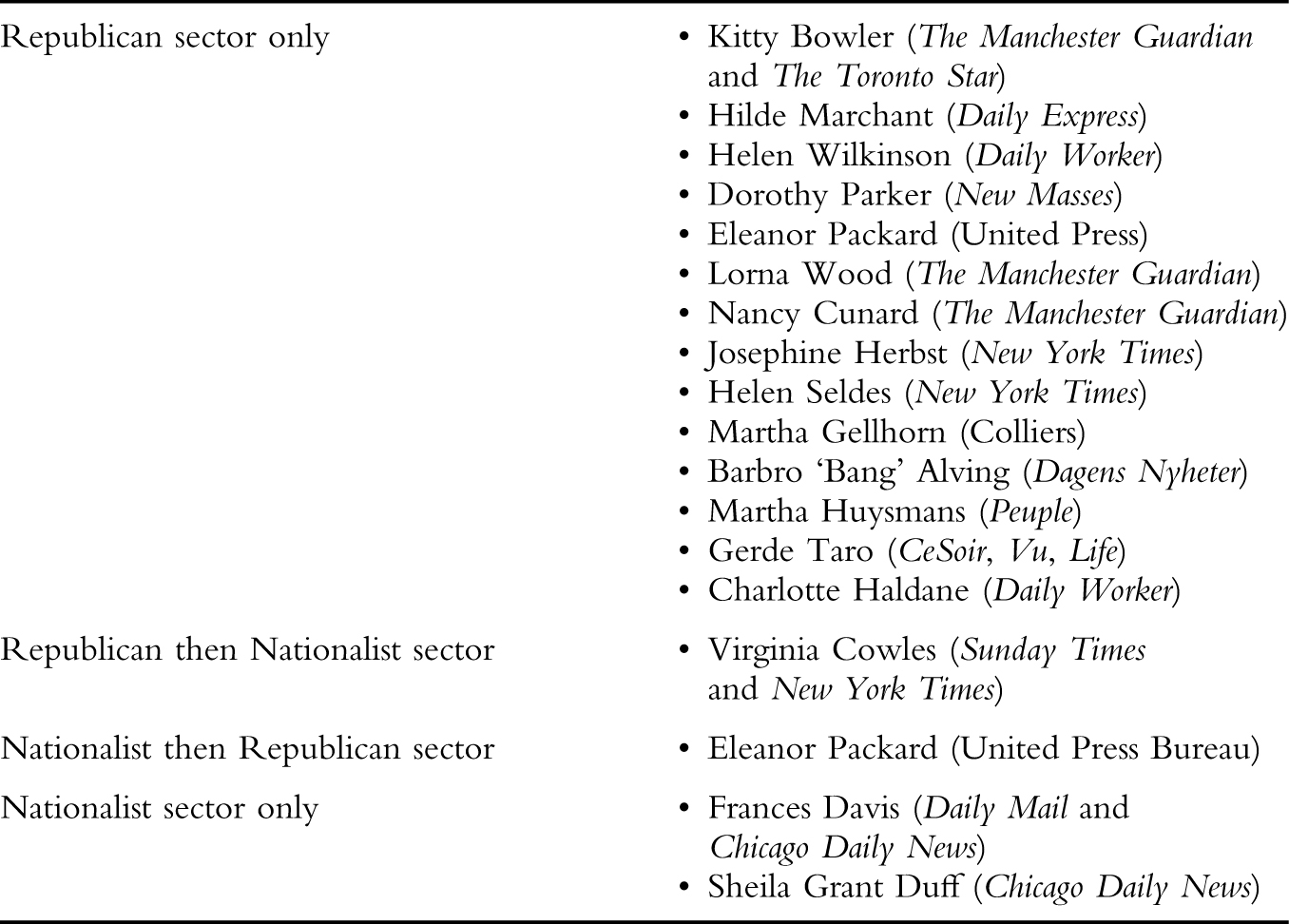

The Spanish Civil War began in July 1936 with the rebellion of Nationalist forces commanded by General Francisco Franco and ended with the defeat of the Republican government in April 1939. Women correspondents represented a small minority of the international press corps that gathered in Spain to witness the events during this period.2 Table 5.1 lists those women I have firmly identified as having visited Spain and provided editorial copy for international news organizations during the war. This list should not be seen definitive for two reasons. It is biased towards British and North American news organizations, which reflects the focus of my wider research into the journalistic representations of the conflict in these contexts (Deacon 2009, forthcoming).

Table 5.1 Female correspondents, their affiliations and areas of operation in the Spanish Civil War.

Furthermore, the list probably excludes the names of other women who worked for Anglo-American news organizations during the war.3 But if the list is not comprehensive, it can be said to include those women whose reporting had most public impact during the conflict and whose contributions have endured over time.

Most of these female correspondents reported from Republican-held territories. To some extent, this differential distribution mirrored a general numerical imbalance in the international news net, which in turn reflected the different attitudes the combatants had towards foreign journalists and their work. Nationalist news management was often autocratic and inflexible, and journalists were treated with suspicion and antipathy (‘A Journalist’, 1937). They were expected to relay Franquist propaganda uncritically, and those who incurred the displeasure of the Nationalist news managers could expect rough treatment. The intimidation and expulsion of correspondents was also evident in Republican-held territories, but these threats were less concerted and not strategically conceived. Journalists had more freedom of movement and, in general terms, Republican news management was framed by a political rather than a military culture, which reflected a clear perception of the need to communicate with international audiences. Within this context, a further gender-specific factor worked to marginalize the presence of female correspondents in Nationalist territories. Most of the women worked for left-wing or left-of-centre newspapers, many of which were banned or restricted by the Nationalists.

However, these structural factors only provide a partial explanation as to why more female reporters covered the war from the Republican side. In particular, they do not address the political agency of these women and how this affected their professional practices. To generate such insight, there is a need to look more closely at the personal and professional lives of these correspondents.

Most of these female correspondents came from privileged backgrounds and were highly educated. Nancy Cunard was the only child of an English baronet and was educated in private schools across Europe. Martha Gellhorn and Kitty Bowler came from wealthy professional families, and both attended the women’s university Bryn Mawr based in Philadelphia. Gerda Taro was born into ‘a bookish family’ in Germany and studied in a commercial school in the Weimar Republic prior to its downfall (Kershaw 2002: 24). Virginia Cowles was able to pursue a journalistic career in Europe as a result of a large personal inheritance (Sebba 1994: 94), and Sheila Grant Duff was the daughter of a lieutenant-colonel and a baronet’s daughter and studied at Oxford University. Such advantages in wealth, class and cultural capital no doubt helped to compensate for the barriers of gender discrimination to some extent, as at that time journalism was deemed an occupation of fairly low social status (even the elite realms of foreign correspondence) (see Cox 1999).4

What these women shared was an antipathy to class and gender conventions and a strong affinity with progressive and left-wing politics. Some had sought to channel their political energies through journalistic activities prior to the outbreak of war in Spain, whereas others became involved in reporting the conflict through more circuitous and serendipitous routes. Virginia Cowles started her career on a small journal called Entre Nous in 1931. Two years later, she started working as a freelancer for the Hearst Press, and then began travelling around Europe filing reports for the Hearst papers on a pay-for-publication basis. Prior to Spain, she visited Italy and Libya and interviewed Mussolini (Sebba 1994: 94–95). Martha Gellhorn abandoned her university studies early to pursue a career as a writer and journalist. In the early 1930s, she travelled Europe as an aspiring foreign correspondent, filing reports for a variety of magazines and newspapers in the US. Sheila Grant Duff graduated from Oxford University in 1934 and became an apprentice of the renowned foreign correspondent Edgar Mowrer of The Chicago Daily News, who was at that stage based in Paris.

Other women correspondents had more tenuous connections with journalism prior to the war. During the 1920s, Nancy Cunard had been involved in a wide range of cultural and artistic activities in Europe. In the late 1920s, she founded the Hours Press and became immersed in a range of progressive political causes, in particular the American civil rights movement (Chisholm 1979: 200–44). She visited Spain on several occasions during the war and was a key figure behind the publication of ‘Authors Take Sides on Spain’, which invited leading literary figures to state their political allegiances in the conflict. Her journalistic involvement only came at the end of the war, when, covering her own personal expenses, she reported on the internment and mistreatment of Republican refugees on the Franco-Spanish border in January and February 1939 for The Manchester Guardian. Her correspondence with the paper’s editor clearly reveals her professional uncertainty and inexperience: ‘Now, I really would feel relieved to know if the articles I have sent are suitable. Give me some criticism, some suggestion – are they too long or too much about refugees?’5

Regardless of their journalistic experience, the female correspondents had little professional status within their news organizations. Apart from Hilde Marchant, who was a staff correspondent at the Daily Express, all the women were employed on a freelance basis, and most secured their commissions after they had arrived in Spain. For example, Frances Davis was an aspiring freelance journalist based in Paris, who rushed to Spain at the start of the war having given little prior thought as to who the combatants were or what issues were at stake. Her recruitment as a special correspondent for The Daily Mail came about accidentally. In the earliest days of the war, she teamed up with a group of male correspondents that included The Daily Mail’s correspondent, Harold Cardozo. The journalists made daily forays over the Franco-Spanish border into the war zone by car and, when it was not possible for the group to return to their French base, Davis took responsibility for couriering the copy over the border. After a lengthy solo trip returning Cardozo’s copy, she had to remonstrate strongly with The Mail’s London desk to get them to take the story. Her tenaciousness created an impression, and she was offered a job by the paper’s editor:

I will carry credentials. I am not excess baggage in a car. I’m not a free-lance doing mail columns. I’m Davis of the Daily Mail.

Davis (1940: 101)

Unlike Davis, Martha Gellhorn was initially drawn to Spain for the struggle rather than the story, but she too gained her commission with Collier’s magazine after her arrival and almost by accident. As she later recollected:

I went to Spain with no intention of writing anything about it…And then somebody said, why don’t you write about life in Madrid? So I just wrote a piece about daily life in Madrid where shells used to hit our hotel everyday, things like that. And sent it off to a friend of mine who worked on Colliers and the next thing I saw I was on the masthead as a war correspondent.6

It is a measure of their junior status that none of the women was recruited to provide daily news. This was often the source of some frustration, as deadlines would have lent discipline and opportunities in their news-gathering activities (e.g. Davis 1940: 84; Cowles 1941: 21; Herbst 1991: 139–40). Instead, the role of the women correspondents was to provide ‘colour stories’ (Davis 1940: 103): reportage that provided human interest and personal context to the hard news stories about political manoeuvrings and military conflicts in the Iberian peninsula.

‘Reportage’ is a term that is often conflated with ‘reporting’ but is actually a distinctive form of journalistic discourse. Whereas reporting requires the eradication of the journalist’s position, in reportage, the author occupies centre stage. As Noel Monks (1955: 95–96), writing two decades after he reported on the conflict for The Daily Express, observed:

These were the days in foreign reporting when personal experiences were copy, for there hadn’t been a war for eighteen years…We used to call them ‘I’ stories, and when the Spanish war ended in 1939 we were as heartily sick of writing them as the public must have been of reading them.

If reportage was a cornerstone of Anglo-US news coverage, reportage from women seemed to have a distinctive quality. Rather than describing the drama and horrors of open combat, their reports focused more frequently upon the impact of the war on ordinary people and their everyday lives. Virginia Cowles (1941: 55) said she was ‘much more interested in the human side – the forces that urged people to such a test of endurance’. Martha Gellhorn wrote about ‘the ordinary people caught up in the war’.7 Both Josephine and Hilde Marchant were separately encouraged by their editors to provide a ‘women’s angle’ on the effect the war was having on daily life (Sebba 1994:91 and 148). According to Angela Jackson (2002: 132), these concerns represented more than just a difference of emphasis:

Women’s writing on Spain frequently allowed space for the personal, and empathy, in many cases overrode detachment. This should not be dismissed as a mere trick for propaganda purposes, aiming to obscure objectivity by an appeal to the emotions. It was, in many cases, a reflection of a different agenda.

It is striking how consistently this empathic approach translated into active sympathy, even advocacy, for the Republic. Many of the women arrived in Spain with their allegiances clearly established. Sheila Grant Duff (1982: 151) felt a ‘passionate commitment to the cause of Spanish freedom’ and in 1937 was sent in to Nationalist territory to discover the fate of the journalist Arthur Koestler, who was then under sentence of death. On this occasion, Duff’s lack of status and experience were seen by her senior colleagues as advantageous, as she would be unknown to Nationalist authorities who were antagonistic towards The Chicago Daily News. So successful was she in slipping under the radar and into the confidences of the military, she was invited to witness the summary execution of Republican prisoners. She immediately appreciated the conflict this created:

For a journalist it would be a sensational coup; for a spy it would really be seeing what Franco’s men were at; for a human being it would be to stand and watch people whom I regarded as friends and allies being put to death in cold blood. I knew I would not be able to live with it. I did not go.

Grant Duff (1976: 81–82)

Martha Gellhorn’s affinity for the Republic endured throughout her life and was unaffected by the vicissitudes of historical revisionism. She claimed never to have read a book on the war because, whatever their factual accuracy, they could not capture ‘the emotion, the commitment, the feeling that we were all in it together, the certainty that we were right’ (quoted in Knightley 1975: 103).

Other female correspondents developed pro-Republican sympathies as a result of their experiences. For example, Virginia Cowles (1941: 55) said that when she first arrived in Spain she ‘had no “line” to take on Spain as it had not yet become a political story for me’. However, it was not long before some strong opinions about the protagonists began to take shape. In Republican Madrid, she took a ‘great liking to the Spanish people’ (ibid.: 35), but later experienced feelings of ‘revulsion’ when witnessing the end of Franco’s Basque offensive, on a press trip organized by the Nationalists to the front at Gijon (ibid.: 85). Although Frances Davis only reported the civil war from the Nationalist sector – and therefore had no equivalent opportunity for making direct comparisons – she, too, came to dislike the Francoists and their supporters. She later wrote of her relationship with Captain Gonzalo de Aguilera, who was a senior Nationalist press officer: ‘I know him for my enemy, and I am his. Everything that has made me is death to him; everything that has made him is death to me’ (Davis 1981: 159).

The difference between those women who arrived in Spain with strong allegiances and those who developed them through their experiences seems to have had some impact upon how they defined their professional roles and responsibilities. Gellhorn memorably dismissed journalistic conventions of balance and neutrality as ‘all that objectivity shit’ (Moorehead 2003: 150) and was unapologetically partisan in her coverage. Similarly, Nancy Cunard saw no reason to mask her outrage at the treatment of the Republican refugees on the French border or her disgust at meeting victorious Falangist troops (Chisholm 1979). In contrast, Victoria Cowles sought to remain dispassionate in her coverage, maintaining an obligation ‘to give both sides a fair hearing’ (Sebba 1994: 103) despite her personal dislike of the Nationalists.

Despite these differences, an overwhelming majority of these women supported the Republican cause. This begs the question as to which parts of the Republic they supported, for the Popular Front was a complex amalgam of communists (Stalinist and anti-Stalinist), socialists, liberals, regional Nationalists and anarcho-syndicalists, and these participants held very different political visions of the purpose and conduct of the war. For the more radical elements, the war was about realizing a genuine social revolution in Spain, based on the wholesale redistribution of land and the formation of collectives. For the more liberal and conservative elements, the war was about preserving liberal democracy against Fascist aggression, a line supported by the Stalinist Communists largely because of the geopolitical interests of the Soviet Union at that time.

In the accounts of the male correspondents who reported on the war directly and were broadly sympathetic to the Republican cause, one typically finds conditional appraisals of the competing factions. Put simply, both radical and liberal correspondents supported the more conservative political forces and shared a deep distrust of the more radical components of the Republican movement (e.g. Steer 1938: 178; Matthews 1938: 286; Buckley 1940: 275; Fischer 1941: 404; Monks 1955: 90–93; North 1958: 140). Such variable and conditional endorsements of the political factions within the Popular Front are signally absent from the accounts the women correspondents provided of their time in Spain. Rather, these women seemed to connect with a broader and undifferentiated conception of the Republic and its values.8 As Josephine Herbst (1991: 135) put it: ‘I have never had much heart for party polemics, and it was not for factionalism I had come to Spain’. But why did these women tend to identify so strongly and unconditionally with the Republic?

One of the indisputably revolutionary elements of the Popular Front was its commitment to gender equality and female emancipation (Nash 1995; Ackelsberg 2005). These ideals contrasted starkly with the chauvinistic codes of traditional Spain, which sequestered the lives of women and which the Nationalists were determined to defend (see Knickerbocker 1936: 44; De la Mora 1939: 53–123). This is not to suggest that these women were disengaged from the wider political issues at stake in the Spanish war – these women were as acutely aware of the anti-Fascist implications of the conflict as their male colleagues – but rather that the gender politics of the conflict added a further powerful connection and identification with the Republic.

A further question is: why did women’s reportage focus so much upon the inner lives and lived experiences of the ‘ordinary’ citizens of the Republic? One way of explaining this is to invoke those strands of feminist theory that identify deep-seated psychological gender differences, such as Carol Gilligan’s (1982) proposition that men are governed by rationalistic concerns about rules and justice whereas women are naturally orientated to an ethics of caring, which privileges emotions, relationships and empathy. However, there is a strong essentialist logic in such explanations that has been criticized by many contemporary feminist theorists (e.g. Oakley 1998; Lister 2003). Moreover, it deflects attention from the material reasons that compelled these women to focus on the politics of the everyday in their writing. As noted, most female correspondents were freelancers with tenuous contractual arrangements with their news organizations. This lack of status restricted their news-gathering opportunities, and many voiced their frustrations at being denied the access, accreditation, transportation and communication facilities provided for their senior male colleagues. However, without the pressures of daily deadlines, these women had more opportunity to integrate with local people and absorb the local culture. There was some inevitability, therefore, that these everyday observations and interactions became a central subject of their work. In Josephine Herbst’s (1991: 139–40) words:

If I had been a regular correspondent, I would have been obliged to show something for each day. But I was on a special kind of assignment, which meant I would write about other subjects than those covered by the news accounts…I did a lot of walking around, looking hard at faces. There was almost nothing to buy except oranges and shoelaces, and all this seemed wonderful to me. The place had been stripped of senseless commodities, and what had been left was the aliveness of speaking faces.

Many women correspondents formed close professional, and sometimes personal, relationships with male colleagues. Lorna Wood, Helen Seldes and Eleanor Packard were all married to senior male journalists and came to Spain because of their partner’s deployment to the region.9 Kitty Bowler entered into a relationship with Tom Wintringham, who initially came to Madrid as a military correspondent for the Daily Worker, was an influential figure in the British Communist party and had a key role in the establishment of the International Brigades. Gerde Taro had been the partner, colleague and agent of Robert Capa before the war and collaborated with him in photo-journalistic work in Spain until her death in July 1937.

The most famous journalistic alliance forged in the Spanish war was between Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway. They became lovers soon after Gellhorn’s arrival in Madrid in March 1937, and this generated some resentment among the other international journalists gathered in the Hotel Florida in Madrid because it delivered Gellhorn greater opportunities in terms of transport and access to influential sources than she would otherwise have had had she remained unattached (Herbst 1991: 138; Moorehead 2003: 142). Gellhorn herself admitted to an element of pragmatism in her relationship with Hemingway. As she dryly commented: ‘I was just about the only blonde in the country. It was much better to belong to someone’.10 The cynicism of this remark needs to be placed in the context of the subsequent, acrimonious breakdown of her relationship with Hemingway, and it is not my intention to suggest that it typifies a calculating motivation on the part of these women correspondents to cultivate male contacts purely out of professional self-interest. Rather, these relationships demonstrate that for all the pioneering, feminist spirit of these women, and despite the spirit of gender equality at the heart of the Republic, their professional environment was highly patriarchal, and their status and opportunities were restricted and facilitated by their male contacts, both in the field and ‘up line’ in the editorial departments of their news organizations.

The significance of editors in the allocation of these women’s roles and the use of their copy links to a final question regarding the role of women correspondents in the war. Why were news organizations so interested in obtaining female perspectives on the war? Despite the low professional status of these women, newspapers often used their contributions prominently, and frequently emphasized the gender of the author. For example, Frances Davis’ articles for the Daily Mail in 1936 were frequently by-lined ‘Only woman correspondent with patriot armies’ and, on several occasions, her gender itself became a topic for coverage (e.g. ‘A girl looks at a battle’, Daily Mail, August 1936). Nancy Cunard’s dispatches in 1939 on the plight of Republican refugees at the Spanish-French border and their internment by the French authorities dominated The Manchester Guardian’s international coverage for several days. As noted previously, Hilde Marchant and Josephine Herbst were instructed by their editors to provide a woman’s perspective on the war.

A range of factors explains this ‘low statushigh profile’ paradox. The first relates to the intense competitiveness and circulation wars of the newspaper industry in the late 1930s, particularly in the UK. Specifically, this was manifested in strenuous attempts by newspapers to dramatise and personalise their coverage of foreign affairs to attract and retain readers (Gannon 1971: 3). The inclusion of women’s perspectives was often used strategically to vitalize foreign coverage. More generally, the 1930s saw an intensification in the ‘feminization of news’ that had began with the Northcliffe revolution at the start of the twentieth century (Tusan 2005: 243). This ‘New Journalism’ was based on a recognition of ‘women consumers as an important audience on their own terms’ (Carter et al. 1998: 1) and involved the inclusion of ‘softer’ news stories – items and features related to lifestyle, human interest and celebrity issues. Here again, the inclusion of feminine perspectives on the personal, emotional and domestic consequences of international events was seen to assist in connecting with these lucrative female markets.

Broader cultural trends also framed the editorial appetite for the kind of empathic reportage of everyday events that these women correspondents provided. The 1930s saw the emergence of the mass observation studies,11 the documentary film movement12 and new photo-journalist publications such as Life and Picture Post that in their separate ways shared an interest in delineating the details and dramas of ordinary lives.

A final reason why women’s views of the Spanish Civil War were valued related to the nature of the war itself. Across Europe, and in the UK in particular, political and public opinion in the 1930s ‘was overshadowed and, to a great extent, determined by an obsessional and, in retrospect, exaggerated fear of air attack’ (Morris 1991: 48). This ‘air fear’ assumed that significant advances in aircraft and bombing technology meant that nations would be defeated by devastating and irresistible aerial assaults on civilian populations. In 1932, the British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin delivered the apocalyptic warning to the House of Commons: ‘The bomber will always get through. The only defence is in offence, which means that you have to kill more women and children more quickly than the enemy if you want to save yourselves’.13 This conviction was a central pillar of Britain’s subsequent policy of appeasement towards the German and Italian dictatorships. As the Spanish Civil War represented the first ‘total war’ on European soil, in which ‘the shadow of the bomber’ removed distinctions between front line and home front, and combatants and civilians, it was inevitable that there would be immense public and media interest in the impact these assaults had on citizens’ lives and morale.

This chapter has examined the important and distinctive contribution that women correspondents made to the coverage of the Spanish Civil War in the international news media. This is not the first study to identify a distinct emphasis and quality to female war reporting and foreign correspondence through history (e.g. Sorel 1999). Indeed, such differences are still identified today. In 1999, Victoria Brittain, deputy foreign editor of The Guardian, asserted:

Men’s response to fear is usually bravado, and in war some male journalists do the same: they become obsessed with weapons and start identifying with the military, in the hope of feeling stronger themselves. Women’s response is to identify with the people whose lives are shattered.

Cited in McLaughlin (2002)

The legitimacy of such distinctions is not accepted by all. For example, McLaughlin (2002: 170) argues: ‘it is certainly wrong to suggest that there is a strict gender difference in style between men and women reporters’. The basis of his objection is that there are plenty of examples in war coverage that do not conform to the pattern, i.e. cases where men provide compassionate reportage about the human and emotional costs of military conflict, and examples where women provide dramatic and significant hard news scoops. With reference to Spain, one can certainly find such exceptions.14 Nevertheless, the tendency for male correspondents to focus on dramatic military events and high-altitude political manoeuvrings in their coverage of the Spanish Civil War and for female correspondents to concentrate on the war’s impact on ordinary lives behind the lines is so obvious that it cannot be ignored. However, I share McLaughlin’s concern about the suspicion of essentialism in many accounts that identify absolute gender differences in war reporting and, indeed, journalism in general. This is not just because it does a disservice to the ‘good guys’ on the international newsbeat, but because these distinctions can inadvertently demean and patronize women’s contributions. As Ann Oakley (1998: 725) notes, the logic of such reasoning ‘…is likely to be the construction of “difference” feminism where women are described as owning distinctive ways of thinking, knowing and feeling, and the danger is that these new moral characterisations will play into the hands of those who use gender as a means of discriminating against women’.

It is not necessary to resort to essentialism to explain why these gender distinctions occurred in Spain. Although highly educated, these women lacked status within their occupational field and were often reliant on the grace-and-favour of male colleagues and editors. This restricted their news-gathering opportunities, in terms of both access to senior political figures and physical mobility. Thus, their interest in reporting the impact of the war on everyday lives was to some extent a case of making a virtue of necessity. Certainly, when some of these women were provided with opportunities to visit the front, they exhibited an equivalent appetite to their male colleagues for observing and reporting battles. They also matched them for bravery and, occasionally, recklessness. On one occasion, this ended in tragedy when the photo-journalist Gerda Taro was crushed to death by a tank during the military retreat of Republican forces from Brunete in July 1937.

Despite the subordinated status of women journalists, news organizations valued and encouraged the production of a female perspective of the war. In part, this represented intensification in the general ‘feminization’ of news during this period, but it also revealed specific public and political interest in the experiences of citizens in coping with the traumas of total war. In this respect, these micro-narratives about everyday experience – which can be seen as symptomatic of the exclusion of women correspondents from wider public affairs – had a subtle but profound impact upon international power politics and military planning. By the late 1930s, the ‘air fear’ that shaped the foreign policy of European democracies through the mid-1930s started to lose credibility. A key reason for this was the eyewitness testimony provided by journalists in Spain, many of them women,15 which showed that civilian morale was stiffened rather than destroyed by air attack and that the devastating impact of incendiaries and bombs could be mitigated by effective air raid precautions. By late 1938, press and political discourses in the UK had shifted decisively towards the development of air raid precautions to help defend civilian populations (Morris 1992: 65). Thus, by identifying resilience and stoicism amid the trauma and suffering, female reportage helped to fortify the political and public will of democratic nations as they prepared to confront the terrible trials in prospect. It is a striking illustration of how the politics of the personal are not only of intrinsic importance, but can also have major, if unforeseen, ‘macro’ political consequences.

1 This chapter draws on research funded by the ESRC (grant reference RES 000–22–0533).

2 Women accounted for 10 per cent of the British and North American correspondents whom I have definitely identified as having been present in Spain at some stage of the conflict

3 For example, in his account of his traumatic incarceration by Nationalist forces in 1937, Arthur Koestler describes meeting a woman who acted in a dual capacity as both a nationalist press officer and correspondent for the Hearst Press in the USA (Koestler 1938: 284–88). Unfortunately, I have yet to identify her.

4 Hilde Marchant was a notable exception in this respect, coming from a working class background.

5 3 February 1939, letter from Cunard to W. P. Crozier, The Manchester Guardian archives.

6 Quoted in Great Lives, BBC Radio 4, 16 January 2007.

7 ‘Martha Gellhorn: On the Record’, BBC4 broadcast, 24 May 2004.

8 Jackson notes that this distaste for factionalism was common among many other women activists who were involved in offering practical and political support to the Republic (2002: 85).

9 Their partners were, respectively, Joseph Swire of Reuters, George Seldes, a radical freelance journalist who submitted copy to the New York Post; and Reynolds Packard of the New York Times.

10 ‘Martha Gellhorn: On the Record’, BBC4 broadcast, 24 May 2004.

11 The first mass observation study commissioned by the British government examined public attitudes to the abdication crisis, but soon expanded into a broad anthropological investigation of the interior lives of British citizens (Hubble 2005).

12 The British Documentary movement, founded by the Scottish film-maker John Grierson and sponsored by the British governmental agencies, was also at its most influential during the late 1930s. This movement was defined by its commitment to social realism in film and conveying the experiences of ‘real places and real people’ (http://www.britmovie.co.uk/history, accessed 20 March 2007).

13 Hansard, 5C/270, 10 November 1932: 632.

14 See, for example, the compassionate reportage by Louis Delaprée who highlighted the suffering of the citizens of Madrid (1937).

15 See, for example, an article by Charlotte Haldane published in the Daily Mirror (8 March 1938: 14) relating her observations on the effects of the bombing of civilians in Madrid and the most effective defence against its worst effects. She concludes: ‘Mothers who want to protect their babies in the next war must be prepared to fight for such protection now’.