“But how do you arrange your documents?”

“In pigeon-holes, partly….”

“Ah, pigeon-holes will not do. I have tried pigeon-holes,

but everything gets mixed in pigeon-holes:

I never know whether a paper is in A or Z.”

George Eliot, Middlemarch

Sitting in my library at night, I watch in the pools of light the implacable plankton of dust shed by both the pages and my skin, hourly casting off layer after dead layer in a feeble attempt at persistence. I like to imagine that, on the day after my last, my library and I will crumble together, so that even when I am no more I’ll still be with my books.

The truth is, I can’t remember a time when I did not live surrounded by my library. By the age of seven or eight, I had assembled in my room a minuscule Alexandria, about one hundred volumes of different formats on all sorts of subjects. For the sake of variety, I kept changing their groupings. I would decide, for instance, to place them by size so that each shelf contained only volumes of the same height. I discovered much later that I had an illustrious predecessor, Samuel Pepys, who in the seventeenth century built little high heels for his smaller volumes, so that the tops all followed a neat horizontal line.34 I began by placing on my lowest shelf the large volumes of picture-books: a German edition of Die Welt, in der wir leben, with detailed illustrations of the world under the sea and life in an autumn undergrowth (even today I can perfectly recall the iridescent fish and the monstrous insects), a collection of stories about cats (from which I still remember the line “Cats’ names and cats’ faces/ Are often seen in public places”), the several titles of Constancio C. Vigil (an Argentine children’s writer who was also a secret collector of pornographic literature), a book of tales and poems by Margaret Wise Brown (it included a terrifying story about a boy who is successively abandoned by the animal, vegetable and mineral kingdoms) and a treasured old edition of Heinrich Hoffmann’s Struwwelpeter in which I carefully avoided the picture of a tailor cutting off a boy’s thumbs with a huge pair of scissors. Next came my books with odd shapes: single volumes of folk tales, a few pop-up books on animals, a tattered atlas which I studied carefully, trying to discover microscopic people in the tiny cities that dotted its continents. On a separate shelf I grouped what I called my “normal-size” books: May Lamberton Becker’s Rainbow Classics, Emilio Salgari’s pirate adventures, a two-volume Childhood of Famous Painters, Roy Rockwood’s Bomba saga, the complete fairy tales of Grimm and Andersen, the children’s novels of the great Brazilian author Monteiro Lobato, Edmundo de Amicis’s infamously sentimental Cuore, full of heroic and long-suffering infants. A whole shelf was given over to the many embossed red-and-blue volumes of a Spanish-language encyclopedia, El Tesoro de la juventud. My Golden Books series, slightly smaller, went on a lower shelf. Beatrix Potter and a German collection of tales from the Arabian Nights formed the last, miniature section.

One of the bookcases that houses Pepys’s collection at the Bodleian Library.

But sometimes this order would not satisfy me and I’d reorganize my books by subject: fairy tales on one shelf, adventure stories on another, scientific and travel volumes on a third, poetry on a fourth, biographies on a fifth. And sometimes, just for the sake of change, I would group my books by language, or by colour, or according to my degree of fondness for them. In the first century A.D., Pliny the Younger described the joys of his place in the country, and among these a sunny room where “one wall is fitted with shelves like a library to hold the books I read and reread.”35 At times, I’ve thought of having a library that consisted of nothing but my most thumbed volumes.

Then there would be groupings within groupings. As I learned then, but was not able to articulate until much later, order begets order. Once a category is established, it suggests or imposes others, so that no cataloguing method, whether on shelf or on paper, is ever closed unto itself. If I decide on a number of subjects, each of these subjects will require a classification within its classification. At a certain point in the ordering, out of fatigue, boredom or frustration, I’ll stop this geometrical progression. But the possibility of continuing it is always there. There are no final categories in a library.

A private library, unlike a public one, presents the advantage of allowing a whimsical and highly personal classification. The invalid writer Valéry Larbaud would have his books bound in different colours according to the language in which they were written, English novels in blue, Spanish in red, etc. “His sickroom was a rainbow,” said one of his admirers, “that allowed his eye and his memory surprises and expected pleasures.”36 The novelist Georges Perec once listed a dozen ways in which to classify one’s library, “none satisfactory in itself.”37 He halfheartedly suggested the following orders:

~ alphabetically

~ by continent or country

~ by colour

~ by date of purchase

~ by date of publication

~ by format

~ by genre

~ by literary period

~ by language

~ according to our reading priorities

~ according to their binding

~ by series

Such classifications may serve a singular, private purpose. A public library, on the other hand, must follow an order whose code can be understood by every user and which is decided upon before the collection is set up on the shelves. Such a code is more easily applied to an electronic library, since its cataloguing system can, while serving all readers, also allow a superimposed program to classify (and therefore locate) titles entered in no predetermined order, without having to be constantly rearranged and updated.

Sometimes the classification precedes the material ordering. In my library in the reconstructed barn, long before my books were put away in obedient rows, they clustered in my mind around specific subject-headings that probably made sense to me alone. It seemed therefore an easy task, when in the summer of 2003 I started to arrange my library, to file into specific spaces the volumes already consigned to a clear set of categories. I soon discovered that I had been overly confident.

For several weeks I unpacked the hundreds of boxes that had, until then, taken up the whole of the dining-room, carried them into the empty library and then stood bewildered among teetering columns of books that seemed to combine the vertical ambition of Babel with the horizontal greed of Alexandria. For almost three months I sifted through these piles, attempting to create some kind of order, working from early in the morning to very late at night. The thick walls kept the room cool and peaceful, and the rediscovery of old and forgotten friends made me oblivious of the time. Suddenly I would look up and find that it was dark outside, and that I had spent the entire day filling only a few expectant shelves. Sometimes I worked throughout the night, and then I would imagine all kinds of fantastical arrangements for my books that later, in the light of day, I dismissed as sadly impractical.

Unpacking books is a revelatory activity. Writing in 1931, during one of his many moves, Walter Benjamin described the experience of standing among his books “not yet touched by the mild boredom of order,”38 haunted by visions of the times and places he had collected them, of the circumstantial evidence that rendered each volume truly his. I too, during those summer months, was overwhelmed by these visions: a ticket fluttering away from an opened book reminded me of a tram ride in Buenos Aires (trams stopped running in the late sixties) when I first read Julian Green’s Moira; a name and phone number inscribed on a fly-leaf brought back the face of a friend long lost who gave me a copy of the Cantos of Ezra Pound; a paper napkin with the logo of the Café de Flore, folded inside Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, attested to my first trip to Paris in 1966; a letter from a teacher inside a collection of Spanish poetry made me think of distant classes where I first heard of Góngora and Vicente Gaos. “Habent sua fata libelli,” says Benjamin, quoting the forgotten medieval essayist Maurus. “Books have their own fates.” Some of mine have waited half a century to reach this tiny place in western France, for which they were seemingly destined.

I had, as I have said, previously conceived of organizing my library into several sections. Principal among these were the languages in which the books were written. I had formed vast mental communities of those works written in English or Spanish, German or French, whether poetry or prose. From these linguistic pools I would exclude certain titles that belonged to subjects of interest to me, such as Greek Mythology, Monotheistic Religions, Legends of the Middle Ages, Cultures of the Renaissance, First and Second World Wars, History of the Book. … My choice of what to lodge under these categories might seem whimsical to many readers. Why stash the works of Saint Augustine in the Christianity section rather than under Literature in Latin or Early Medieval Civilizations? Why place Carlyle’s French Revolution in Literature in English rather than in European History, and not Simon Schama’s Citizens? Why keep Louis Ginzberg’s seven volumes of Legends of the Jews under Judaism but Joseph Gaer’s study on the Wandering Jew under Myths? Why place Anne Carson’s translations of Sappho under Carson but Arthur Golding’s Metamorphoses under Ovid? Why keep my two pocket volumes of Chapman’s Homer under Keats?

Ultimately, every organization is arbitrary. In libraries of friends around the world, I have found many odd classifications: Rimbaud’s Le Bateau ivre under Sailing, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe under Travel, Mary McCarthy’s Birds of America under Ornithology, Claude Lévi-Strauss’s The Raw and the Cooked under Cuisine. But public libraries have their own odd approaches. One reader was upset because, in the London Library, Stendhal was listed under “B” for his real name, Beyle, and Gérard de Nerval under “G.” Another complained that, in the same library, Women were classed “under the Miscellaneous end of Science,” after Witchcraft and before Wool and Wrestling.39 In the Library of Congress’s catalogues, the subject-headings include such curious categories as:

~ bat binding

~ boots and shoes in art

~ chickens in religion and folklore

~ sewage: collected works

It is as if the contents of the books matter less to these organizers than the uniqueness of the subject under which they are catalogued, so that a library becomes a collection of thematic anthologies. Certainly, the subjects or categories into which a library is divided not only change the nature of the books it contains (read or unread) but also, in turn, are changed by them. To place Robert Musil’s novels in a section on Austrian Literature circumscribes his work by nationalistic definitions of novel-writing; at the same time, it illuminates neighbouring sociological and historical works on the Austro-Hungarian Empire by expanding their restrictive scholarly views on the subject. Inclusion of Anton Chekhov’s Strange Confession in the section of Detective Novels forces the reader to follow the story with the requisite attention to murder, clues and red herrings; it also opens the notion of the crime genre to authors such as Chekhov, not usually associated with the likes of Raymond Chandler and Agatha Christie. If I place Tomás Eloy Martínez’s Santa Evita in my section on Argentinian History do I diminish the book’s literary value? If I place it under Fiction in Spanish am I dismissing its historical accuracy?

Sir Robert Cotton, an eccentric seventeenth-century English bibliophile, ranged his books (which included many rare manuscripts, such as the only known manuscript of Beowulf, and the Lindisfarne Gospels, from about A.D. 698) in twelve bookcases, each adorned with the bust of one of the first twelve Caesars. When the British Library acquired some of his collection, it kept Cotton’s strange cataloguing system, so that the Lindisfarne Gospels can today be requested as “Cotton MS. Nero D. IV” because it was once the fourth book on the fourth shelf down in the bookcase topped by the bust of Nero.40

And yet order of almost any kind has the merit of containing the uncontainable. “There is probably many an old collector,” G.K. Chesterton observed, “whose friends and relations say that he is mad on Elzevirs, when as a matter of fact it is the Elzevirs that keep him sane. Without them he would drift into soul-destroying idleness and hypochondria; but the drowsy regularity of his notes and calculations teaches something of the same lesson as the swing of the smith’s hammer or the plodding of the ploughman’s horses, the lesson of the ancient commonsense of things.”41 The ordering of a collection of thrillers, or of books printed by Elzevir, grants the manic behaviour of the collector a certain degree of sanity. At times I feel as if the exquisite pocket-sized leather-bound Nelsons, the flimsy Brazilian booklets known as literatura de cordel (because they were sold by hawkers who strung their wares on thin cords), the early editions of the Séptimo Círculo detective series edited by Borges and Bioy Casares, the small square volumes of the New Temple Shakespeare published by Dent and illustrated with wood engravings by Eric Gill—all these books that I sporadically collect—have kept me sane.

Several examples of literatura de cordel.

The broader the category, the less circumscribed the book. In China, at the beginning of the third century, the books in the Imperial Library were kept under four modest and comprehensive headings agreed upon by eminent court scholars—canonical or classical texts, works of history, philosophical works, and miscellaneous literary works—each bound in a specific and symbolic colour, respectively green, red, blue and grey (a chromatic division curiously akin to that of the early Penguins or the Spanish Colección Austral). Within these groupings, the titles were shelved following graphic or phonetic orderings. In the first case, many thousands of characters were broken into a few basic elements—the ideogram for earth or water, for instance—and then placed in a conventional order that followed the hierarchies of Chinese cosmology. In the second, the order was based on the rhyme of the last syllable of the last word in a title. Equivalent to the Roman alphabetical system, which fluctuates between 26 (English) and 28 (Spanish) letters, the number of possible rhymes in Chinese varied between 76 and 206. The largest manuscript encyclopedia in the world, the Yongle Dadian, or Monumental Compendium from the Era of Eternal Happiness, commissioned in the fifteenth century by the Emperor Chengzu with the purpose of recording in one single publication all existing Chinese literature, used the rhyming method to order its thousands of entries. Over two thousand scholars worked on the ambitious enterprise. Only a small portion of that monstrous catalogue survives today.42

Entering a library, I am always struck by the way in which a certain vision of the world is imposed upon the reader through its categories and its order. Some categories, of course, are more evident than others, and Chinese libraries in particular have a long history of classification that reflects, in its variety, the changing ways in which China has conceived the universe. The earliest catalogues follow the hierarchy imposed by a belief in the supreme rule of the gods, beneath whose primordial, all-encompassing vault—the realm of the heavenly bodies—stands the subservient earth. Then, in decreasing order of importance, come human beings, animals, plants and, lastly, minerals. These six categories govern the divisions under which the works of 596 authors, preserved in 13,269 scrolls, are classified in the first-century bibliographic study known as the Hanshu Yiwenzhi, or Dynastic History of the Han, an annotated catalogue based on the research of two imperial librarians, Liu Xiang and his son Liu Xin,43 who, alone, dedicated their lives to recording what others had written. Other Chinese catalogues stem from different hierarchies. The Cefu Yuangui, or Archives of the Divinatory Tortoise, compiled by imperial command between 1005 and 1013, follows not a cosmic order but rather a bureaucratic one, beginning with the emperor and descending through the various state officials and institutions down to lowly citizens.44 (In Western terms, we could conceive of a library of English literature that began, for instance, with the Prayers and Poems of Elizabeth I and ended with the complete works of Charles Bukowski.) This bureaucratic or sociological order was employed to assemble one of the first Chinese encyclopedias to call itself exhaustive: the Taiping Yulan, or Imperial Readings from the Era of the Great Peace. Finished in 982, it explored all fields of knowledge; its sequel, Vast Compendium from the Era of the Great Peace, covered under fifty-five subject-headings more than five thousand biographical entries, and listed over two thousand titles. Song Taizong, the emperor who commanded its writing, is said to have read three chapters a day for one whole year. A more complex ordering system appears in what is known as the largest encyclopedia ever printed: the Qinding Gujin Tushu Jicheng, or Great Illustrated Imperial Encyclopedia of Past and Present Times, of 1726, a gigantic biographical library divided into more than ten thousand sections. The work was attributed to Jiang Tingxi, a court proofreader who used wooden blocks with cut-out pictures and movable characters specially designed for the enterprise. Each section of the encyclopedia covers one specific realm of human concern, such as Science or Travel, and is divided into subsections containing biographical entries. The section on Human Relations, for instance, lists the biographies of thousands of men and women according to their occupation or position in society, among them sages, slaves, playboys, tyrants, doctors, calligraphers, supernatural beings, great drinkers, notable archers and widows who did not marry again.45

One of the volumes of the monumental Yongle Dadian encyclopedia.

Five centuries earlier, in Iraq, the renowned judge Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Khalikan had compiled a similar “mirror of the world.” His Obituaries of Celebrities and Reports of the Sons of Their Time encompassed 826 biographies of poets, rulers, generals, philologists, historians, prose writers, traditionalists, preachers, ascetics, viziers, Koranic expositors, philosophers, physicians, theologians, musicians and judges—providing, among other features, the subject’s sexual preferences, professional merits and social standing. Because Khalikan’s “biographical library” was meant to “entertain as well as edify,” he omitted from his great work entries on the Prophet and his companions.46 Unlike the Chinese encyclopedias, Khalikan’s opus was arranged in alphabetical order.

The alphabetical classification of books was first used over twenty-two centuries ago, by Callimachus, one of the most notable librarians of Alexandria, a poet admired by Propertius and Ovid, and the author of over eight hundred books, including a 120-volume catalogue of the most important Greek authors in the Library.47 Ironically, given that he so laboriously strove to preserve the works of the past for future readers, all that remains of Callimachus’s own work today is six hymns, sixty-four epigrams, a fragment of a little epic and, most important, the method he used to catalogue his voluminous readings. Callimachus had devised a system for his critical inventory of Greek literature that divided the material into tables or pinakes, one for each genre: epic, lyric, tragedy, comedy, philosophy, medicine, rhetoric, law and, finally, a grab-bag of miscellany.48 Callimachus’s main contribution to the art of keeping books, inspired perhaps by methods employed in the vanished Mesopotamian libraries, was to list the chosen authors alphabetically, with biographical notes and a bibliography (also alphabetically ordered) appended to each consecrated name. I find it moving to think that, were Callimachus to wander into my library, he would be able to find the two volumes of what remains of his own works, in the Loeb series, by following the method he himself conceived to shelve the works of others.

The alphabetical system entered the libraries of Islam by way of Callimachus’s catalogues. The first such work composed in the Arab world, in imitation of the pinakes, was the Book of Authors, by the Baghdad bookseller Abu Tahir Tayfur, who died in A.D. 893. Though only the title has come down to us, we know that the writers selected by Tayfur were each given a short biography and a catalogue of important works listed in alphabetical order.49 About the same time, Arab scholars in various learning centres, concerned with lending order to Plato’s dialogues so as to facilitate translation and commentaries, discovered that Callimachus’s alphabetic method, which enabled readers to find a certain author in his allotted shelf, did not lend the same rigour to the placement of the texts themselves. Consulting the various bibliographies of Plato’s work compiled by the long-gone librarians of Alexandria, they discovered to their astonishment that these ancient sages, in spite of following Callimachus’s system, had rarely been in agreement as to what went where. All had agreed that Plato’s works, for example, were to be classified under “P,” but in what order or within which subgroupings? The scholarly Aristophanes of Byzantium, for instance, had gathered Plato’s work in triads (excluding several dialogues for no clear reason), while the learned Thrasylus had divided what he assumed to be “the genuine dialogues” into sets of four, saying that Plato himself had always “published his dialogues in tetralogies.”50 Other librarians had listed the collected works in one single grouping but in different sequences, some beginning with the Apology, others with the Republic, others still with Phaedrus or Timaeus. My library suffers from the same confusion. Since my authors are listed in alphabetical order, all of Margaret Atwood’s books are to be found under the letter “A,” on the third shelf down of the English language section, but I don’t pay much attention to whether Life before Man precedes Cat’s Eye (for the sake of respecting the chronology), or Morning in the Burned House follows Oryx and Crake (separating her poetry from her fiction).

In spite of such minor frailties, the Arab libraries that flourished in the late Middle Ages were catalogued using alphabetical order. It would otherwise have been impossible to consult a repertoire of books as lengthy as that of the Nizamiyya College in Damascus, where, we are told, a Christian scholar was able to peruse, in 1267, the fifty-sixth volume of a catalogue that listed nothing but works on several subjects “written during the Islamic period up to the reign of Caliph Mustansir in 1241.”51

If a library is a mirror of the universe, then a catalogue is a mirror of that mirror. While in China the notion of listing all a library’s books between the covers of a single book was imagined almost from the start, in the Arab world it did not become common until the fifteenth century, when catalogues and encyclopedias frequently bore the name “Library.” The greatest of these annotated catalogues, however, was compiled at a much earlier date. In 987, Ibn al-Nadim (of whom we know little, except that he was probably a bookseller in the service of the Abbasid rulers of Baghdad) set out to assemble

the catalogue of all the books of all peoples, Arab and foreigners, existing in the Arab tongue, as well as their writings on the various sciences, together with an account of the life of those who composed them and the social standing of these authors with their genealogies, the date of their birth, the length of their life, the time of their death, and their cities of origin, their virtues and their faults, from the beginning of the invention of each science up to our own age, the year 377 of the Hegira.

Al-Nadim did not work only from previous bibliographies; his intention, he tells us in his preface, is to “see for himself” the works in question. For this purpose he visited as many libraries as he had knowledge of, “opening volume after volume and reading through scroll after scroll.” This all-encompassing work, known as the Fihrist, is in fact the best compendium we have of medieval Arab knowledge; it combines in one volume “memory and inventory” and is “a library in its own right.”52

The Fihrist is a unique literary creation. It does not follow Callimachus’s alphabetical order, nor is it divided according to the location of the volumes it lists. Meticulously chaotic and delightfully arbitrary, it is the bibliographical record of a boundless library dispersed throughout the world and visible only in the shape al-Nadim chose to give it. In its pages, religious texts sit side by side with profane ones, scientific works grounded in arguments of authority are listed together with writings belonging to what al-Nadim called the rational sciences, while Islamic studies are paired with studies of the beliefs of foreign nations.53 Both the unity and the variety of the Fihrist lie in the eye and mind of its omnivorous author.

But a reader’s ambition knows no bounds. A century later, the vizier Abul-Qasim al-Maghribi, dissatisfied with what he deemed to be an incomplete work, composed a Complement to the Catalogue of al-Nadim that extended the already inconceivable repertory to an even more astonishing length. The volumes listed in this exaggerated catalogue were likewise, of course, never collected in one place.

Looking for more practical ways to find their path through a maze of books, Arab librarians often allowed themes and disciplines to override the strictures of the alphabetical system and to impose subject divisions on the physical space itself. Such was the library visited towards 980 by a contemporary of al-Nadim, the distinguished doctor Abou Ali El-Hossein Ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna. Paying a visit to his patient the Sultan of Bukhara, in what is today Uzbekistan, Avicenna discovered a library conveniently divided into scholarly subjects of all sorts. “I entered a building of many rooms,” he tells us.

In each room there were chests full of books, piled one on top of the other. In one room were poetry books in Arabic, in another books of law, and so forth; each room was given over to books of one specific science. I consulted the catalogue of Ancient Works [i.e., Greek] and asked the librarian, keeper of the live memory of the books, for what I wanted. I saw books whose very titles are for the most part unknown, books I had never seen before and which I have never seen since. I read these books and I profited from them, and I was able to recognize each one’s position inside its proper scientific category.54

These thematic divisions were commonly used together with the alphabetical system in the Islamic Middle Ages. The subjects themselves varied, as did the place in which the books were kept, whether open shelves, closed cupboards or (as in the case of the Bukhara Library) wooden chests. Only the category of sacred books—the Koran, in a variety of copies—was always kept separate, since the word of God is not to be mixed with the word of men.

The cataloguing methods of the Library of Alexandria, with its space organized according to the letters of the alphabet and its books subjected to hierarchies imposed by the selected bibliographies, reached far beyond the borders of Egypt. Even the rulers of Rome created libraries in Alexandria’s image. Julius Caesar, who had lived in Alexandria and had certainly frequented the Library, sought to establish in Rome “the finest possible public library,” and charged Marcus Terence Varro (who had written an unreliable handbook of library science, quoted approvingly by Pliny) “to collect and classify all manner of Greek and Latin books.”55 The task was not carried out until after Caesar’s death; in the first years of the reign of Augustus, Rome’s first public library was opened by Asinius Pollio, a friend of Catullus, Horace and Virgil. It was housed in the so-called Atrium of Freedom (its exact location has not yet been established) and decorated with portraits of famous writers.

Roman libraries like that of Asinius Pollio, specially designed to suit the learned reader in spite of names such as “Atrium of Freedom,” must have felt powerfully like a place of containment and order. The earliest remains we have of such a library were unearthed on the Palatine Hill in Rome. Because Roman book collections such as Pollio’s were bilingual, architects had to design in duplicate the buildings housing them. The Palatine ruins, for instance, reveal one chamber for Greek works and one for works in Latin, each with openings for statues and deep niches for wooden bookcases (armaria), while the walls appear to have been lined with shelves and protected by doors. The armaria were labelled and their codes inscribed in the catalogues next to the titles of the books they contained. Flights of stairs allowed readers to reach the different thematic areas and, since some of the shelves were higher than arm’s length, portable steps were available for those who required them. A reader would have picked up the desired scroll, aided perhaps by the cataloguing librarian, and unfurled it on one of the tables in the middle of the room, to examine it in the midst of a communal mumbling, in the days before silent reading became common, or carried it out and read it under the colonnade, as was customary in the libraries of Greece.56

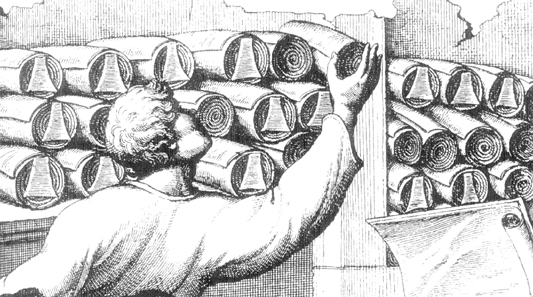

But this is only guesswork. The single depiction we have of a Roman library derives from a line drawing, made in the nineteenth century, of a relief from the Augustan period found in Neumagen, Germany, and now lost.57 It shows the scrolls lying in tiers of three on deep shelves, probably in alphabetical order within their subject section, their triangular identifying tags clearly visible to the reader, who is stretching his right arm towards them. Unfortunately, the titles on the tags cannot be read. As in any library I visit, I am curious to know what the books are, and even here, faced with the image of an image of a long-vanished collection, my eyes peer into the drawing, trying to make out the names of those ancient scrolls.

A library is an ever-growing entity; it multiplies seemingly unaided, it reproduces itself by purchase, theft, borrowings, gifts, by suggesting gaps through association, by demanding completion of sorts. Whether in Alexandria, Baghdad or Rome, this expanding mass of words eventually requires systems of classification that allow it space to grow, movable fences that save it from being restricted by the limits of the alphabet or rendered useless by the sheer quantity of items it might hold under a categorical label.

Engraving copied from a no longer extant Roman bas-relief, depicting the method for storing scrolls.

Numbers seem perhaps better suited than letters or subject-headings to maintain order in this unstoppable growth. Even in the seventeenth century, Samuel Pepys realized that, to allow for this surfeit, the infinite universe of numbers was more efficient than the alphabet, and he enumerated his volumes for his “easy finding them to read.”58 The numerical classification I remember from my visits to the school library (and the one most widely used throughout the world) is Dewey’s, which lends the spines of books the aspect of licence plates on rows of parked cars.

Portrait of Melvil Dewey.

Melvil Dewey’s story is a curious combination of a generous vision and narrow views. In 1873, while still a student at Amherst College, Massachusetts (where he soon after became acting librarian), the twenty-two-year-old Dewey realized the need for a system of classification that would combine both common sense and practicality. He disliked arbitrary methods, such as that of the New York State Library he had frequented, by which books were arranged alphabetically but “paying no attention to subjects,” and so he set himself the task of conceiving a better system. “For months I dreamed night and day that there must be somewhere a satisfactory solution,” he wrote fifty years later. “One Sunday during a long sermon … the solution flasht over me so that I jumpt in my seat and came very near shouting ‘Eureka!’ Use decimals to number a classification of all human knowledge in print.”59

Following the subject divisions of earlier scholars, Dewey ambitiously divided the vast field of “all human knowledge in print” into ten thematic groups, and then assigned to each group one hundred numbers which in turn were broken down into a further ten, allowing for a progression ad infinitum. Religion, for instance, received the number 200; the Christian Church, the number 260; the Christian God, the number 264.60 The advantage of what became known as the Dewey Decimal Classification System is that, in principle, each division can be subjected to countless further divisions. God himself can suffer being broken down into his attributes or his avatars, and each attribute and each avatar can undergo yet another fragmentation. That Sunday in church, young Dewey discovered a method of great simplicity and effectiveness that allowed for the huge measure of its task. “My heart is open to anything that’s either decimal or about libraries,” he once confessed.61

Though Dewey’s method could be applied to any grouping of books, his vision of the world, reflected in his thematic divisions, was surprisingly restricted. According to one of his biographers, Dewey “espoused ‘Anglo-Saxonism,’ an American doctrine that touted the unique virtues, mission and destiny of the Anglo-Saxon ‘race….’ So convinced was he of the rightness of ‘Anglo-Saxonism’ that he based his definition of ‘objectivity’ on it.”62 It never seems to have occurred to him that to conceive a universal system that limited the universe to what appeared important to the inhabitants of a small northern island and their descendants was at best insufficient, and at worst defeated its own all-embracing purpose. Mr. Podsnap, in Our Mutual Friend, constructs his sense of identity by dismissing everything he doesn’t understand or care for as “not English!,” believing that what he puts behind him, he instantly puts out of existence, with “a peculiar flourish of his right arm.”63 Dewey understood that he could not do this in a library, especially a limitless library, but he decided instead that everything “not Anglo-Saxon” could somehow be forced to fit into categories of Anglo-Saxon devising.

For practical reasons, however, Dewey’s system, a reflection of his time and place, became hugely popular, mainly because it was easily memorized since its pattern was repeated in every subject. The system has been variously revised, simplified and adapted, but essentially Dewey’s basic premise remains unchanged: everything conceivable can be attributed a number, so that the infinity of the universe can be contained within the infinite combination of ten digits.

Dewey continued working on his system throughout his life. He believed in adult education for those not fully schooled, in the moral superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race, in simplified spelling that would not force students to memorize the irregularities of the English language (he dropped the “le” at the end of “Melville” shortly after graduating) and would “speed the assimilation of non-English-speaking immigrants into the dominant American culture.” He also believed in the importance of public libraries. Libraries, he thought, had to be instruments of easy use “for every soul.” He argued that the cornerstone of education was not just the ability to read but the knowledge of how “to get the meaning from the printed page.”64 It was in order to facilitate access to that page that he dreamt up the system for which he is remembered.

Ordered by subject, by importance, ordered according to whether the book was penned by God or by one of God’s creatures, ordered alphabetically or by numbers or by the language in which the text is written, every library translates the chaos of discovery and creation into a structured system of hierarchies or a rampage of free associations. Such eclectic classifications rule my own library. Ordered alphabetically, for instance, it incongruously marries humorous Bulgakov to severe Bunin (in my Russian Literature section), and makes formal Boileau follow informal Beauchemin (in Writing in French), properly allots Borges a place next to his friend Bioy Casares (in Writing in Spanish) but opens an ocean of letters between Goethe and his inseparable friend Schiller (in German Literature).

Not only are such methods arbitrary, they are also confusing. Why do I place García Márquez under “G” and García Lorca under “L”?65 Should the pseudonymous Jane Somers be grouped with her alter ego, Doris Lessing? In the case of books written by two or more writers, should the hierarchy of ABC dictate the book’s position, or (as with Nordhoff and Hall) should the fact that the authors are always mentioned in a certain order override the system? Should a Japanese author be listed according to Western or Eastern nomenclature, Kenzaburo Oe under “O” or Oe Kenzaburo under “K”? Should the once-popular historian Hendrik van Loon go under “V” or “L”? Where should I keep the delightful Logan Pearsall Smith, author of my much-loved All Trivia? Alphabetical order sparks peculiar questions for which I can offer no sensible answer. Why are there more writers whose names (in English, for instance) begin with “G” than “N” or “H”? Why are there more Gibsons than Nichols and more Grants than Hoggs? Why more Whites than Blacks, more Wrights than Wongs, more Scotts than Frenches?

The novelist Henry Green, attempting to explain his difficulty in putting names to faces in his fiction, had this to say:

Names distract, nicknames are too easy and if leaving both out as it often does makes a book look blind then that to my mind is no disadvantage. Prose is not to be read aloud but to oneself alone at night, and it is not quick as poetry but rather a gathering web of insinuations which go further than names however shared can ever go. Prose should be a long intimacy between strangers with no direct appeal to what both may have known. It should slowly appeal to feelings unexpressed, it should in the end draw tears out of the stone, and feelings are not bounded by the associations common to place names or to persons with whom the reader is unexpectedly familiar.66

My thematic and alphabetic library allows me that long intimacy in spite of names and in spite of appealing to what I have known, awakening feelings for which I have no words except those on the page, and experience of which I have no memory except that of the printed story. To know whether a certain book exists in my library, I have to either rely on my memory (did I once buy that book? did I lend it? was it returned?) or on a cataloguing system like Dewey’s (which I am reluctant to undertake). The former forces me to exercise a daily relationship with my books, many unopened for long periods, unread but not forgotten, by going repeatedly through the shelves to see what is there and what is not. The latter lends certain books, which I have acquired from other libraries, mysterious notations on their spines that identify them as having belonged to a nameless phantom reader from the past, cabbalistic concatenations of letters and numbers that once gave them a place and a category, far away and long ago.

Some nights I dream of an entirely anonymous library in which books have no title and boast no author, forming a continuous narrative stream in which all genres, all styles, all stories converge, and all protagonists and all locations are unidentified, a stream into which I can dip at any point of its course. In such a library, the hero of The Castle would embark on the Pequod in search of the Holy Grail, land on a deserted island to rebuild society from fragments shored against his ruins, speak of his first centenary encounter with ice and recall, in excruciating detail, his early going to bed. In such a library there would be one single book divided into a few thousand volumes and, pace Callimachus and Dewey, no catalogue.