“No room! No room!” they cried out when they saw Alice coming.

“There’s plenty of room!” said Alice indignantly, and she sat down in

a large arm-chair at one end of the table.

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

The very fact of knowing that the books in a library are set up according to a rule, whichever that may be, grants them preconceived identities, even before we open their first pages. Before my Wuthering Heights unfolds its misty story, it already proclaims itself a work of Literature in English (the section in which I’ve placed it), a creation of the letter B, a member of some now forgotten community of books (I bought this copy secondhand in Vancouver, where it was allotted the mysterious number 790042B inscribed in pencil on the fly-leaf, corresponding to a classification with which I’m not familiar). It also boasts a place in the aristocracy of chosen books which I take down by design and not by chance (since it sits on the highest shelf, unreachable except with a ladder). Though books are chaotic creations whose most secret meaning lies always just beyond the reader’s grasp, the order in which I keep them lends them a certain definition (however trivial) and a certain sense (however arbitrary)—a humble cause for optimism.

Yet one fearful characteristic of the physical world tempers any optimism that a reader may feel in any ordered library: the constraints of space. It has always been my experience that, whatever groupings I choose for my books, the space in which I plan to lodge them necessarily reshapes my choice and, more important, in no time proves too small for them and forces me to change my arrangement. In a library, no empty shelf remains empty for long. Like Nature, libraries abhor a vacuum, and the problem of space is inherent in the very nature of any collection of books. This is the paradox presented by every general library: that if, to a lesser or greater extent, it intends to accumulate and preserve as comprehensive as possible a record of the world, then ultimately its task must be redundant, since it can only be satisfied when the library’s borders coincide with those of the world itself.

In my adolescence, I remember watching with a kind of fascinated horror, how night after night the shelves on the wall of my room would fill up, apparently on their own, until no promissory nooks were left. New books, lying flat as in the earliest codex libraries, would begin to pile up one on top of the other. Old books, occupying their measured place during the day, would double and quadruple in volume and keep any newcomers at bay. All around me—on the floor, in the corners, under the bed, on my desk—columns of books would slowly rise and transform the space into a saprophyte forest, its sprouting trunks threatening to crowd me out.

Later, in my home in Toronto, I put up bookshelves just about everywhere—in bedrooms and kitchen, corridors and bathroom. Even the covered porch had its shelves, so that my children complained that they felt they required a library card to enter their own home. But my books, in spite of any pride of place granted to them, were never satisfied. Detective Writing, housed in the basement bedroom, would suddenly outgrow the space allotted to it and would have to be moved upstairs to one of the corridor walls, displacing French Literature. French Literature would now have to be reluctantly divided into Literature of Quebec, Literature of France and Literature of Other Francophone Countries. I found it highly irritating to have Aimé Césaire, for instance, separated from his friends Eluard and Breton, and to be forced to exile Louis Hémon’s Maria Chapdelaine (Quebec’s national romantic epic) into the company of books by Huysmans and Hugo, just because Hémon happened to have been born in Brittany and I had no room left in the Québécois section.

Old books that we have known but not possessed cross our path and invite themselves over. New books try to seduce us daily with tempting titles and tantalizing covers. Families beg to be united: volume xviii of the Complete Works of Lope de Vega is announced in a catalogue, calling to the other seventeen that sit, barely leafed through, on my shelf. How fortunate for Captain Nemo to be able to say, during his twenty-thousand-league journey under the sea, that “the world ended for me the day when my Nautilus sank underwater for the first time. On that day I bought my last volumes, my last pamphlets, my last periodicals, and since then, it is for me as if humanity no longer thought nor wrote a single word.”67 But for readers like myself, there are no “last” purchases this side of the grave.

The English poet Lionel Johnson was so pressed for room that he devised shelves suspended from the ceiling, like chandeliers.68 A friend of mine in Buenos Aires constructed columns of four-sided shelves that spun on a central axis, quadrupling the space for his books; he called the shelves his dervish-cases. In the library of Althorp, the Northampton estate of Earl Spencer (which before its sale in 1892 comprised forty thousand volumes, including fifty-eight titles by the first English printer, William Caxton), the bookshelves rose to such dizzying heights that in order to consult the top rows a gigantic ladder was required, consisting of “a sturdy pair of steps on wheels, surmounted by a crow’s nest containing a seat and small lectern, the general effect resembling a medieval siege-machine.”69 Unfortunately, the inventors of these enthusiastic pieces of furniture, like mad geographers intent on extending geography to fit ever-expanding maps, are always defeated. Ultimately, the number of books always exceeds the space they are granted.

The mahogany library steps at Althorp, designed by John King. They are nine feet tall, with a seat and book-rest, and were originally backed by green silk curtains.

In the second chapter of Sylvie and Bruno, Lewis Carroll dreamt up the following solution: “If we could only apply that Rule to books! You know, in finding the Least Common Multiple, we strike out a quantity wherever it occurs, except in the term where it is raised to its highest power. So we should have to erase every recorded thought, except in the sentence where it is expressed with the greatest intensity.” His companion objects: “Some books would be reduced to blank paper, I’m afraid!” “They would,” the narrator admits. “Most libraries would be terribly diminished in bulk. But just think what they would gain in quality!”70 In a similar spirit, in Lyons, at the end of the first century, a strict law demanded that, after every literary competition, the losers be forced to erase their poetic efforts with their tongues, so that no second-rate literature would survive.71

In a manuscript kept in the Vatican Library (and as yet unpublished), the Milanese humanist Angelo Decembrio describes a drastic culling system by which the young fifteenth-century prince Leonello d’Este furnished his library in Ferrara under the supervision of his teacher, Guarino da Verona.72 Leonello’s system was one of exclusion, rejecting everything except the most precious examples of the literary world. Banished from the princely shelves were monastic encyclopedic works (“oceans of story, as they are called, huge burdens for donkeys,”)73 French and Italian translations of classic texts (but not the originals), and even Dante’s Commedia, “which may be read on winter nights, by the fire, with the wife and the children, but which does not merit being placed in a scholarly library.”74 Only four classical authors were admitted: Livy, Virgil, Sallust and Cicero. All others were considered minor authors whose work could be bought from any street vendor and lent to friends without fear of losing anything of great worth.

In order to find ways to cope with volume growth (though not always concerned with gaining quality), readers have resorted to all manner of painful devices: pruning their treasures, double-shelving, divesting themselves of certain subjects, giving away their paperbacks, even moving out and leaving the house to their books. Sometimes none of these options seems endurable. Shortly after Christmas 2003, a forty-three-year-old New York man, Patrice Moore, had to be rescued by firefighters from his apartment after spending two days trapped under an avalanche of journals, magazines and books that he had stubbornly accumulated for over a decade. Neighbours heard him moaning and mumbling through the door, which had been blocked by all the paper. Not until the lock was broken with a crowbar and rescuers began digging into the entombing piles of publications was Moore found, in a tiny corner of his apartment, literally buried in books. It took over an hour to extricate him; fifty bags of printed material had to be hauled out before this constant reader could be reached.75

In the 1990s, conscious that their old, stately buildings were no longer able to contain the flood of printed matter, the directors of several major libraries decided to erect new premises to lodge their vast collections. In Paris and London, Buenos Aires and San Francisco (among others), plans were laid out and construction began. Unfortunately, in several cases the design of the new libraries proved ill suited to house books. To compensate for the deficient planning of the new main San Francisco Public Library, in which the architect had not allowed for a sufficiently large amount of shelving space, the administrators pulled hundreds of thousands of books from the library’s hold and sent them to a landfill. Since books were selected for destruction on the basis of the length of time they had sat unrequested, in order to save as many books as possible, heroic librarians crept into the stacks at night and stamped the threatened volumes with false withdrawal dates.76

Patrice Moore’s book-clogged apartment in New York City.

To sacrifice the contents in order to spare the container—not only the San Francisco Public Library suffered from such an inane action. Even the Library of Congress in Washington, “the purported library of last resort,” became the victim of equally irresponsible behaviour. In 1814, during negotiations by the American Congress to purchase the private library of former American president Thomas Jefferson—to replace the books British troops had burned earlier that year after occupying the Capitol Building in Washington—Cyril King, the Federalist Party lawmaker, objected, “The Bill would put $23,900 into Mr Jefferson’s pocket for about 6,000 books—good, bad and indifferent; old, new and worthless, in languages which many cannot read, and most ought not to.” Jefferson answered, “I do not know that my library contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from their collection: there is, in fact, no subject to which a Member of Congress may not have occasion to refer.”77

Over a century and a half later, Jefferson’s observation has been all but forgotten. In 1996, the New Yorker reporter (and best-selling novelist) Nicholson Baker heard that the Library of Congress was replacing most of its enormous collection of late-nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century newspapers with microfilms and then destroying the originals. The justification for this official act of vandalism was based on “fraudulent” scientific studies on the acidity and embrittlement of paper, something like defending a murder by calling it a case of assisted suicide. Several years of research later, Baker reached the conclusion that the situation was even worse than he had at first feared. Nearly all major university libraries in the United States, as well as most large public libraries, had followed the Library of Congress’s example, and some of the rarest periodicals no longer existed except in microfilmed versions.78 And these versions are faulty, in many ways. Microfilms suffer from smudges, stains and scratches; they cut off text at the margins, and often skip entire sections.

The microfilming culprits were not all American. In 1996 the British Library, whose collection of newspapers had, to a large degree, escaped the bombings of the Second World War, got rid of more than sixty thousand volumes of collected newsprint, mainly non-Commonwealth journals printed after 1850. A year later, it chose to discard seventy-five runs of Western European publications; shortly afterwards, it gave away its collections of periodicals from Eastern Europe, South America and the United States. In each case, the papers had been microfilmed; in each case, the reason given for the removal of the originals was space. But as Baker argues, microfilms are difficult to read and their reproduction qualities are poor. Even the newer electronic technologies cannot approach the experience of handling an original publication. As any reader knows, a printed page creates its own reading space, its own physical landscape in which the texture of the paper, the colour of the ink, the view of the whole ensemble acquire in the reader’s hands specific meanings that lend tone and context to the words. (Columbia University’s librarian Patricia Battin, a fierce advocate for the microfilming of books, disagreed with this notion. “The value,” she wrote, “in intellectual terms, of the proximity of the book to the user has never been satisfactorily established.”79 There speaks a dolt, someone utterly insensitive, in intellectual or any other terms, to the experience of reading.)

The Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

But above all, the argument that calls for electronic reproduction on account of the endangered life of paper is a false one. Anybody who has used a computer knows how easy it is to lose a text on the screen, to come upon a faulty disk or CD, to have the hard drive crash beyond all appeal. The tools of the electronic media are not immortal. The life of a disk is about seven years; a CD-ROM lasts about ten. In 1986, the BBC spent two and a half million pounds creating a computer-based, multimedia version of the Domesday Book, the eleventh-century census of England compiled by Norman monks. More ambitious than its predecessor, the electronic Domesday Book contained 250,000 place names, 25,000 maps, 50,000 pictures, 3,000 data sets and 60 minutes of moving pictures, plus scores of accounts that recorded “life in Britain” during that year. Over a million people contributed to the project, which was stored on twelve-inch laser disks that could only be deciphered by a special BBC microcomputer. Sixteen years later, in March 2002, an attempt was made to read the information on one of the few such computers still in existence. The attempt failed. Further solutions were sought to retrieve the data, but none was entirely successful. “There is currently no demonstrably viable technical solution to this problem,” said Jeff Rothenberg of the Rand Corporation, one of the world experts on data preservation, called in to assist. “Yet, if it is not solved, our increasingly digital heritage is in grave risk of being lost.”80 By contrast, the original Domesday Book, almost a thousand years old, written in ink on paper and kept at the Public Record Office in Kew, is in fine condition and still perfectly readable.

The Domesday Book in sections, in its present state.

The director for the electronic records archive program at the National Archives and Records Administration of the United States confessed in November 2004 that the preservation of electronic material, even for the next decade, let alone for eternity, “is a global problem for the biggest governments and the biggest corporations all the way down to individuals.”81 Since no clear solution is available, electronic experts recommend that users copy their materials onto CDs, but even these are of short duration. The lifespan of data recorded on a CD with a CD burner could be as little as five years. In fact, we don’t know for how long it will be possible to read a text inscribed on a 2004 CD. And while it is true that acidity and brittleness, fire and the legendary bookworms threaten ancient codexes and scrolls, not everything written or printed on parchment or paper is condemned to an early grave. A few years ago, in the Archeological Museum of Naples, I saw, held between two plates of glass, the ashes of a papyrus rescued from the ruins of Pompeii. It was two thousand years old; it had been burnt by the fires of Vesuvius, it had been buried under a flow of lava—and I could still read the letters written on it, with astonishing clarity.

And yet, both libraries—the one of paper and the electronic one—can and should coexist. Unfortunately, one is too often favoured to the detriment of the other. The new Library of Alexandria, inaugurated in October 2003, proposed, as one of its major projects, a parallel virtual library—the Alexandria Library Scholars Collective. This electronic library was set up by the American artist Rhonda Roland Shearer, and requires an annual operating budget of half a million American dollars, a sum likely to increase considerably in the future. These two institutions, both attempts to reincarnate the ancient library of Callimachus’s time, present a paradox. While the shelves of the new stone and glass library stand almost empty for lack of financial resources, displaying a meagre collection of paperbacks and castoffs plus donations from international publishers, the virtual library is being filled with books from all over the world, scanned for the most part by a team of technicians at Carnegie-Mellon University and using software called CyberBook Plus, developed by Shearer herself and designed to allow for different formats and languages “with heavy emphasis on visual rather than posted texts.”82

The Alexandria Library Scholars Collective is not unique in its ambition to compete with paper libraries. In 2004 the most popular of all Internet search services, Google, announced that it had concluded agreements with several of the world’s leading research libraries—Harvard, the Bodleian, Stanford, the New York Public Library—to scan part of their holdings and make the books available on-line to researchers, who would no longer have to travel to the libraries themselves or dust their way through endless stacks of paper and ink.83 Though, for financial and administrative reasons, Google cancelled its project in July 2005, it will doubtless be resurrected in the future, since it is so obviously suited to the capabilities of the Web. In the next few years, in all probability, millions of pages will be waiting for their online readers. As in the cautionary tale of Babel, “nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do,”84 and we shall soon be able to summon up the whole of the ghostly stock of all manner of Alexandrias past or future, with the mere tap of a finger.

The practical arguments for such a step are irrefutable. Quantity, speed, precision, on-demand availability are obviously important to the researching scholar. And the birth of a new technology need not mean the death of an earlier one: the invention of photography did not eliminate painting, it renewed it, and the screen and the codex can feed off each other and coexist amicably on the same reader’s desk. In comparing the virtual library to the traditional one of paper and ink, we need to remember several things: that reading often requires slowness, depth and context; that our electronic technology is still fragile and that, since it keeps changing, it prevents us many times from retrieving what was once stored in now superseded containers; that leafing through a book or roaming through shelves is an intimate part of the craft of reading and cannot be entirely replaced by scrolling down a screen, any more than real travel can be replaced by travelogues and 3-D gadgets.

Perhaps this is the crux. Reading a book is not perfectly equivalent to reading a screen, no matter what the text. Watching a play is not equivalent to seeing a film, seeing a film is not equivalent to viewing a DVD or videotape, gazing upon a painting is not equivalent to examining a photograph. Every technology provides a medium (the dictum was pronounced in 1964 by Marshall McLuhan85) that characterizes the work it embodies, and defines its optimum storage and access. Plays can be performed in circular spaces that are ill-suited for the projection of films; a DVD seen in an intimate room has a different quality from the same film seen on a large screen; photos well-reproduced in a book can be fully appreciated by the viewer, while no reproduction allows the full experience of seeing an original painting.

Baker ends his book with four useful recommendations: that libraries be obliged to publish the lists of the publications they intend to discard; that all publications sent to and rejected by the Library of Congress be indexed and stocked in ancillary buildings provided by the state; that newspapers routinely be bound and saved; that either the program to microfilm or digitize books should be abolished, or it should become obligatory not to destroy the originals after they are electronically processed. Together, electronic storage and the physical preservation of printed matter grant a library the fulfillment of at least one of its ambitions: comprehensiveness.

BELOW LEFT: Title page of the first edition of Naudé’s book.

BELOW RIGHT: A stupa with its printed Buddhist text.

Or, if nothing else, a certain measure of comprehensiveness. The nineteenth-century American scholar Oliver Wendell Holmes admonished, “Every library should try to be complete on something, if it were only the history of pinheads,”86 echoing the sentiments of the French scholar Gabriel Naudé, who in 1627 published a modest Advice for Setting Up a Library (revised and expanded several years later) in which he went even further in the reader’s demands. “There is nothing,” Naudé wrote, “that renders a Library more recommendable, than when every man finds in it that which he is looking for and cannot find anywhere else; therefore the perfect motto is, that there exists no book, however bad or badly reviewed, that may not be sought after in some future time by a certain reader.”87 These remarks demand from us an impossibility, since every library is, by needs, an incomplete creation, a work-in-progress, and every empty shelf announces the books to come.

And yet it is for those empty spaces that we hoard knowledge. In the year 764, after the suppression of the Emi Rebellion, the Japanese Empress Shotoku, believing that the end of the world was near, decided to leave a record of her times for whatever new generations might rise from the ashes. Following her orders, four dharani-sutra (essential words of wisdom transcribed into Chinese from the Sanskrit) were printed from woodblocks on strips of paper and inserted into small wooden stupas—representations of the universe that depict the square base of the earth and the ascending circles of the heavens fixed around the staff of the Lord Buddha. These stupas were then distributed among the ten leading Buddhist temples of the empire.88

The empress imagined that she could preserve in this way a distillation of the accumulated knowledge up to her time. Ten centuries later, in 1751, her project was unknowingly restated by Denis Diderot, the co-editor (with Jean le Rond d’Alembert) of the greatest publishing project of the French Enlightenment, the Encyclopédie, ou, Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts, et des métiers.

It is odd that the man who would later be accused of being one of the Catholic Church’s fiercest enemies (the Encyclopédie was placed on the Church’s Index of Forbidden Books and Diderot was threatened with excommunication) should have begun his scholarly career as a devout Jesuit student. Diderot was born in 1713, seventy-six years before the beginning of the French Revolution. Having attended the Jesuit College at Langres as a child, in his early twenties he became an ardent and pious believer. He refused the comforts of his family home (his father was a wealthy master cutler of international fame), took to wearing a hair shirt and sleeping on straw, and eventually, urged on by his religious instructors, decided to run away and enter holy orders. Alerted to the plan, his father barred the door and demanded to know where his son was going at midnight. “To Paris, to join the Jesuits,” said Diderot. “Your wishes will be granted,” his father replied, “but it will not be tonight.”89

Diderot Senior kept his promise only in part. He sent his son to complete his education in Paris, where he attended not the Jesuit Collège Louis-le-Grand but the Collège d’Harcourt, founded by the Jansenists (followers of an austere religious school of thought whose tenets were similar in many ways to those of Calvinism), and later the University of Paris. Diderot’s intention to obtain a doctorate in theology was never fulfilled. Instead, he studied mathematics, classical literature and foreign languages without a definite goal in mind, until his father, alarmed at the prospect of having an eternal student on his hands, cut off all financial support and ordered the young man home. Diderot disobeyed, and for the next several years earned his living in Paris as a journalist and a teacher.

Diderot and d’Alembert met when the former had just turned thirty. D’Alembert was four years younger but had already distinguished himself in the field of mathematics. He possessed (according to a contemporary account) a “luminous, profound and solid mind”90 that much appealed to Diderot. A foundling who had been abandoned as a baby on the steps of a Paris church, d’Alembert was someone with little concern for social prestige; he maintained that the motto of every man of letters should be “Liberty, Truth and Poverty,” the latter achieved, in his case, with no great effort.

Some fifteen years before their meeting, in 1728, the Scottish scholar Ephraim Chambers had published a fairly comprehensive Cyclopedia (the first in the English language, and no relation to the present-day Chambers) that inspired various other such works, among them Dr. Johnson’s Dictionary. Early in 1745, the Paris bookseller André-François Le Breton, unable to secure the translation of the Cyclopedia into French, engaged the services first of d’Alembert and then of Diderot to edit a similar work but on a vaster scale. Arguing that the Cyclopedia was, to a large extent, a pilfering of a number of French texts, Diderot suggested that to translate the work back into what was effectively its original tongue would be a senseless exercise; better to collect new material and offer readers a comprehensive and up-to-date panorama of what the arts and sciences had produced in recent times.

In a game of self-reflecting mirrors, Diderot defined his grand twenty-eight-volume publication (seventeen volumes of text and eleven of illustrations) in an article titled “Encyclopédie” in that same Encyclopédie: “The goal of the Encyclopédie,” he wrote, “is to assemble the knowledge scattered over the surface of the globe and to expose its general system to the men who come after us, so that the labours of centuries past do not prove useless to the centuries to come…. May the Encyclopédie become a sanctuary in which human knowledge is protected from time and from change.”91 The notion of an encyclopedia as a sanctuary is appealing. In 1783, eleven years after the completion of Diderot’s monumental project, the writer Guillaume Grivel imagined this sanctuary as the cornerstone of a future society which, like the one imagined by the Japanese empress, must rebuild itself from its ruins. In the first volume of a novel recounting the adventures of a group of new Crusoes shipwrecked on an uncharted island, Grivel describes how the new colonists rescue several volumes of Diderot’s Encyclopédie from their wreck and, on the basis of its learned articles, attempt to reconstruct the society they have been forced to leave behind.92

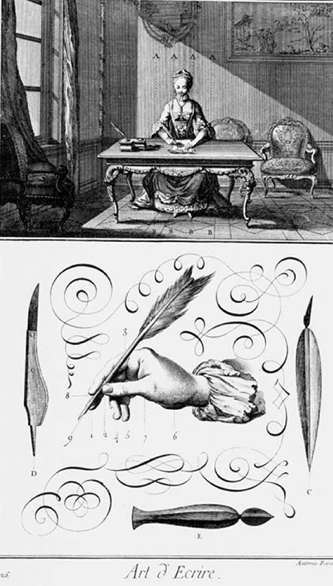

The Encyclopédie was also conceived as an archival and interactive library. In the prospectus that announced the vast project, Diderot declared that it would “serve all the purposes of a library for a professional man on any subject apart from his own.” Defending his decision to arrange this comprehensive “library” in alphabetical order, Diderot explained that it would not destroy liaison between subjects nor violate “the tree of knowledge” but, on the contrary, the system would be made visible in “the disposition of the materials within each article and by the exactitude and frequency of cross-references.”93 What he was proposing by these cross-references was to present the diverse articles not as independent texts, each occupying the exclusive field of a given subject, but as a crossweaving of subjects that would in many cases “occupy the same shelf.” Thus he imagined his “library” as a room in which different “books” were placed in a single space. A discussion of calvinism, which, on its own, would have aroused the censorious eye of the Church, is included in an entry on geneva; a critical assessment of the Church’s sacraments is implied in a cross-reference such as “anthropophagy: see eucharist, communion, ALTAR, etc.”

Sometimes he quoted a foreign character (a Chinese savant, a Turk) to voice criticism of religious dogma, simultaneously including the description of other cultures or philosophies; sometimes he took a word in its broadest sense, so that, for example, under adoration he was able to discuss both the worship of God and that of a beautiful woman, daringly associating one with the other.

The first volume of the Encyclopédie sold quickly, in spite of its high price. By the time the second volume appeared, in 1752, the Jesuits were so enraged by what was in their eyes obvious blasphemy that they urged Louis xv to issue a royal ban. Since one of Louis’s daughters had fallen deathly ill, his confessor convinced him that “God might save her if the King, as a token of piety, would suppress the Encyclopédie.”94 Louis obeyed, but the Encyclopédie resumed publication a year later, thanks to the efforts of the Royal Director of Publications (a sort of minister of Communications), the enlightened Lamoignon de Malesherbes, who had gone as far as suggesting to Diderot that he hide the manuscripts of future volumes in Malesherbes’s own house until the conflict blew over.

Though Diderot does not explicitly mention space in his statement of purpose, the notion of knowledge occupying a physical place is implicit in his words. To assemble scattered knowledge is, for Diderot, to ground that knowledge on a page, and the page between the covers of a book, and the book on the shelves of a library. An encyclopedia can be, among many other things, a space-saving device, since a library endlessly divided into books requires an ever-expanding home that can take on nightmare dimensions. Legend has it that Sarah Winchester, widow of the famous gun-maker whose rifle “won the West,” was told by a medium that as long as construction on her California house continued, the ghosts of the Indians killed by her husband’s rifle would be kept at bay. The house grew and grew, like a thing in a dream, until its hundred and sixty rooms covered six acres of ground; this monster is still visible in the heart of Silicon Valley.95 Every library suffers from this urge to increase in order to pacify our literary ghosts, “the ancient dead who rise from books to speak to us” (as Seneca described them in the first century A.D.),96 to branch out and bloat until, on some inconceivable last day, it will include every volume ever written on every subject imaginable.

One warm afternoon in the late nineteenth century, two middle-aged office clerks met on a bench on the Boulevard Bourdon in Paris and immediately became the best of friends. Bouvard and Pécuchet (the names Gustave Flaubert gave to his two comic heroes) discovered through their friendship a common purpose: the pursuit of universal knowledge. To achieve this ambitious goal, next to which Diderot’s achievement appears delightfully modest, they attempted to read everything they could find on every branch of human endeavour, and cull from their readings the most outstanding facts and ideas, an enterprise that was, of course, endless. Appropriately, Bouvard and Pécuchet was published unfinished one year after Flaubert’s death in 1880, but not before the two brave explorers had read their way through many learned libraries of agriculture, literature, animal husbandry, medicine, archaeology and politics, always with disappointing results. What Flaubert’s two clowns discovered is what we have always known but seldom believed: that the accumulation of knowledge isn’t knowledge.97

A page from Diderot’s Encyclopédie, illustrating the entry on “Writing.”

Bouvard and Pécuchet’s ambition is now almost a reality, when all the knowledge in the world seems to be there, flickering behind the siren screen. Jorge Luis Borges, who once imagined the infinite library of all possible books,98 also invented a Bouvard-and-Pécuchet-like character who attempts to compile a universal encyclopedia so complete that nothing in the world would be excluded from it.99 In the end, like his French forerunners, he fails in his attempt, but not entirely. On the evening on which he gives up his great project, he hires a horse and buggy and takes a tour of the city. He sees brick walls, ordinary people, houses, a river, a marketplace, and feels that somehow all these things are his own work. He realizes that his project was not impossible but merely redundant. The world encyclopedia, the universal library, exists, and is the world itself.