“I lived off art, I lived off love,

I never harmed a living soul….

Why then, Lord,

Why do You reward me thus?”

Puccini, Tosca, Act II

Like the Dead Sea scrolls, like every book that has come down to us from the hands of distant readers, each of my books holds the history of its survival. From fire, water, the passage of time, neglectful readers and the hand of the censor, each of my books has escaped to tell me its story.

A few years ago, in a stand at the Berlin flea market, I found a thin black book bound in hard cloth covers that bore no inscription whatsoever. The title page, in fine Gothic lettering, declared it to be a Gebet-Ordnung für den Jugendgottesdienst in der jüdißchen Gemeinde zu Berlin (Sabbath-Nachmittag) [Order of Prayer for Youth Service in the Jewish Community of Berlin (Sabbath-Evening)]. Among the prayers is included one “for our king, Wilhelm II, Kaiser of the German Realm” and his “Empress and Queen Auguste-Victoria.” This was the eighth edition, printed by Julius Gittenfeld in Berlin in 1908, and had been bought at the bookstore of C. Boas Nachf. on Neue Friedrichstraße 69, “at the corner of Klosterstraße,” a corner that no longer exists. There was no indication of the name of the owner.

The German prayer book printed in Berlin in 1908.

A year before the book was printed, Germany had refused the armament limitations proposed by the Hague Peace Conference; a few months later, the expropriation law decreed by Reichskanzler and Preußischer Ministerpräsident Fürst Bernhard von Bülow authorized further German settlements in Poland; in spite of hardly ever being used against Polish landowners, this law granted Germany early territorial rights that in turn, in June 1940, allowed the establishment of a concentration camp in Auschwitz. The original owner of the Gebet-Ordnung probably bought or was given the book when he was thirteen years old, the age at which he would have his bar mitzvah and be permitted to join in synagogue prayers. If he survived the First World War, he would have been thirty-eight on the birth of the Third Reich in 1933; if he stayed on in Berlin, it is likely that he was deported, like so many other Berlin Jews, to Poland.253 Perhaps he had time to give the prayer book to someone before being taken away; perhaps he hid it, or left it behind with other books he had collected.

After the Nazis began their looting and destruction of the Jewish libraries, the librarian in charge of the Sholem Aleichem Library in Biala Podlaska decided to save the books by carting away, day after day, as many as he and a colleague could manage, even though he believed that very soon “there would be no readers left.” After two weeks the holdings had been moved to a secret attic, where they were discovered by the historian Tuvia Borzykowski long after the war ended. Writing about the librarian’s action, Borzykowski remarked that it was carried out “without any consideration as to whether anyone would ever need the saved books”:254 it was an act of rescuing memory per se. The universe, the ancient cabbalists believed, is not contingent on our reading it; only on the possibility of our reading it.

With the emblematic book-burning in a square on Unter den Linden, opposite the University of Berlin, on the evening of 10 May, 1933, books became a specific target of the Nazis. Less than five months after Hitler became chancellor, the new propaganda minister of the Reich, Dr. Joseph Goebbels, declared that the public burning of books by authors such as Heinrich Mann, Stefan Zweig, Freud, Zola, Proust, Gide, Helen Keller and H.G. Wells allowed “the soul of the German people again to express itself. These flames not only illuminate the final end of an old era; they also light up the new.”255 The new era proscribed the sale or circulation of thousands of books, in either shops or libraries, as well as the publishing of new ones. Volumes commonly kept on sitting-room shelves because they were prestigious or entertaining became suddenly dangerous. Private holdings of the indexed books were prohibited; many books were confiscated and destroyed. Hundreds of Jewish libraries throughout Europe were burnt down, both personal collections and public treasure-houses. A Nazi correspondent gleefully reported the destruction of the famous library of the Lublin Yeshiva in 1939:

For us it was a matter of special pride to destroy the Talmudic Academy, which was known as the greatest in Poland…. We threw the huge talmudic library out of the building and carried the books to the market place, where we set fire to them. The fire lasted twenty hours. The Lublin Jews assembled around and wept bitterly, almost silencing us with their cries. We summoned the military band, and with joyful shouts the soldiers drowned out the sounds of the Jewish cries.256

At the same time, the Nazis decided to spare a number of books for commercial and archival purposes. In 1938 Alfred Rosenberg, one of the principal Nazi theoreticians, proposed that Jewish collections, including both secular and religious literature, should be preserved in an institute set up to study “the Jewish question.” Two years later, the Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage was opened in Frankfurt am Main. To procure the necessary material, Hitler himself authorized Rosenberg to create a task force of expert German librarians, the notorious ERR, Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg.257 Among the confiscated collections incorporated to the institute were those of the rabbinical seminaries of Breslau and Vienna, the Hebraica and Judaica departments of the Frankfurt Municipal Library, the Collegio Rabbinico in Rome, the Societas Spinoziana in The Hague and the Spinoza Home in Rijnsburg, the Dutch publishing companies Querido, Pegazus and Fischer-Berman,258 the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, Beth Maidrash Etz Hayim, the Israelitic seminary of Amsterdam, the Portuguese Israelitic seminary and the Rosenthaliana, Rabbi Moshe Pessah in Volos, the Strashun Library in Vilna (the grandson of the founder committed suicide when ordered to assist with the cataloguing), libraries in Hungary (a parallel institute on “the Jewish question” was set up in Budapest), libraries in Denmark and Norway and dozens of libraries in Poland (especially the great library of the Warsaw synagogue and of the Institute for Jewish Studies). From these vast hoards, Rosenberg’s henchmen selected the books to be sent to his institute; all others were destroyed. In February 1943 the institute issued the following directives for the selection of library material: “all writings which deal with the history, culture, and nature of Judaism, as well as books written by Jewish authors in languages other than Hebrew and Yiddish, must be shipped to Frankfurt.” But “books in Hebrew script (Hebrew or Yiddish) of recent date, later than the year 1800, may be turned to pulp; this applies also to prayer books, Memorbücher, and other religious works in the German language.”259 Regarding the many Torah scrolls, it was suggested that “perhaps the leather can be put to use for bookbinding.” Miraculously, my prayer book escaped.

Seven months after these directives were given, in September 1943, the Nazis set up a “family camp” as an extension of the Auschwitz precinct, in the birch forest of Birkenau, which included a separate block, “number 31,” built especially for children. It was designed to serve as proof to the world that Jews deported to the east were not being killed. In fact, they were allowed to live six months before being sent on to the same fate as the other deported victims. Eventually, having served its purpose as propaganda, the “family camp” was permanently closed.260

While it lasted, Block 31 housed up to five hundred children together with several prisoners appointed “counsellors,” and in spite of the severe surveillance it possessed, against all expectations, a clandestine children’s library. The library was minuscule; it consisted of eight books, which included H.G. Wells’s A Short History of the World, a Russian school textbook and an analytical geometry text. Once or twice an inmate from another camp managed to smuggle in a new book, so that the number of holdings rose to nine or ten. At the end of each day, the books, together with other valuables such as medicines and bits of food, would be entrusted to one of the older girls, whose responsibility it was to hide them in a different place every night. Paradoxically, books that were banned throughout the Reich (those by H.G. Wells, for instance) were sometimes available in concentration camp libraries.

Although eight or ten books made up the physical collection of the Birkenau children’s library, there were others that circulated through word of mouth alone. Whenever they could escape surveillance, the counsellors would recite to the children books they had themselves learned by heart in earlier days, taking turns so that different counsellors “read” to different children every time; this rotation was known as “exchanging books in the library.”261

It is almost impossible to imagine that under the unbearable conditions imposed by the Nazis, intellectual life could still continue. The historian Yitzhak Schipper, who was writing a book on the Khazars while he was an inmate of the Warsaw ghetto, was asked how he did his work without being able to sit and research in the appropriate libraries. “To write history,” he answered, “you need a head, not an ass.”262

Liberation of the survivors of the Birkenau Concentration Camp.

There was even a continuation of the common, everyday routines of reading. This persistence adds to both the wonder and the horror: that in such nightmarish circumstances men and women would still read about Hugo’s Jean Valjean and Tolstoy’s Natasha, would fill in request cards and pay fines for late returns, would discuss the merits of a modern author or follow once again the cadenced verses of Heine. Reading and its rituals became acts of resistance; as the Italian psychologist Andrea Devoto noted, “everything could be treated as resistance because everything was prohibited.”263

In the concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen, a copy of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain was passed around among the inmates. One boy remembered the time he was allotted to hold the book in his hands as “one of the highlights of the day, when someone passed it to me. I went into a corner to be at peace and then I had an hour to read it.”264 Another young Polish victim, recalling the days of fear and discouragement, had this to say: “The book was my best friend, it never betrayed me; it comforted me in my despair; it told me that I was not alone.”265

“Any victim demands allegiance,” wrote Graham Greene,266 who believed it was the writer’s task to champion victims, to restore their visibility, to set up warnings that, by means of an inspired craft, will act as touchstones for something approaching understanding. The authors of the books on my shelves cannot have known who would read them, but the stories they tell foresee or imply or witness experiences that may not yet have taken place.

Because the victim’s voice is all-important, oppressors often attempt to silence their victims: by literally cutting out their tongues, as in the case of the raped Philomela in Ovid, and Lavinia in Titus Andronicus, or by secreting them away, as the king does with Segismundo in Calderón’s Life Is a Dream, or as Mr. Rochester does to his mad wife in Jane Eyre, or by simply denying their stories, as in the professorial addendum in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. In real life, victims are “disappeared,” locked up in a ghetto, sent to prison or a torture camp, denied credibility. The literature on my shelves tells over and over again the victim’s story, from Job to Desdemona, from Goethe’s Gretchen to Dante’s Francesca, not as mirror (the German surgeon Johann Paul Kremer warned in his Auschwitz diary, “By comparison, Dante’s inferno seems almost a comedy”267) but as metaphor. Most of these stories would have been found in the library of any educated German in the 1930s. What lessons were learned from those books is another matter.

In Western culture, the archetypal victim is the Trojan princess Polyxena. The daughter of Priam and Hecuba, she was supposed to marry Achilles but her brother Hector opposed the union. Achilles stole into the temple of Apollo to catch sight of her, but was discovered there and murdered. According to Ovid, after the destruction of Troy the spirit of Achilles appeared to the victorious Greeks as they were about to embark, and demanded that the princess be sacrificed to him. Accordingly, she was dragged to Achilles’ tomb and killed by Achilles’ son Neoptolemus. Polyxena is perfect for the victim’s role: innocent of cause, innocent of blame, innocent of benefiting others with her death, a blank page haunting the reader with unanswered questions. Arguments, however specious, were made by the Greeks to find reasons for the ghost’s request, to justify compliance with the sacrifice, to excuse the blade that Achilles’ son drove into her bared breast. But no argument can convince us that Polyxena’s death was merited. The essence of her victimhood—as of all victimhood—is injustice.

My library witnesses the injustice suffered by Polyxena, and all fictional phantoms who lend voice to countless ghosts who were once solid flesh. It does not clamour for revenge, another constant subject of our literatures. It argues that the strictures that define us as a social group must be constructive or cautionary, not wilfully destructive, if they are to have any sane collective meaning—if the injury to a victim is to be seen as an injury to society as a whole, in recognition of our common humanity. Justice, as the English dictum has it, must not only be done, it must be seen to be done. Justice must not seek a private sense of satisfaction, but must publicly lend strength to society’s self-healing impulse to learn. If justice takes place, there may be hope, even in the face of a seemingly capricious divinity.

A Hasidic legend collected by Martin Buber tells of a man who took God to trial. In Vienna, a decree was issued that would make the difficult life of the Jews of Polish Galicia even harder. The man argued that God should not turn his people into victims, but should allow them to toil for him in freedom. A tribunal of rabbis agreed to consider the man’s arguments, and considered, as was proper, that both plaintiff and defendant retire during their deliberations. “The plaintiff will wait outside; we cannot ask You, Lord of the Universe, to withdraw, since your glory is omnipresent. But we will not allow You to influence us.” The rabbis deliberated in silence and with their eyes closed. Later that evening, they called the man and told him their verdict: his argument was just. At that very same hour, the decree was cancelled.268

In Polyxena’s world, the outcome is less happy. God, the gods, the Devil, nature, the social system, the world, the primum mobile, refuses to acknowledge guilt or responsibility. My library repeats again and again the same question: Who makes Job endure so much pain and loss? Who is to blame for Winnie’s sinking in Beckett’s Happy Days? Who relentlessly destroys the life of Gervaise Macquart in Zola’s L’assommoir? Who victimizes the protagonists of Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance?

Throughout history, those confronted with the unbearable account of the horrors they have committed—torturers, murderers, merciless wielders of power, shamelessly obedient bureaucrats—seldom answer the question “why?” Their impassive faces reject any admission of guilt, reflect nothing but a refusal to move from the past of their deeds into the consequences. Yet the books on my shelves can help me imagine their future. According to Victor Hugo, hell takes on different shapes for its different inhabitants: for Cain it has the face of Abel, for Nero that of Agrippina.269 For Macbeth, hell bears the face of Banquo; for Medea, that of her children. Romain Gary dreamt of a certain Nazi officer condemned to the constant presence of the ghost of a murdered Jewish clown.270

If time flows endlessly, as the mysterious connections between my books suggest, repeating its themes and discoveries throughout the centuries, then every misdeed, every treason, every evil act will eventually find its true consequences. After the story has stopped, just beyond the threshold of my library, Carthage will rise again from the strewn Roman salt. Don Juan will confront the anguish of Doña Elvira. Brutus will look again on Caesar’s ghost, and every torturer will have to beg his victim’s pardon in order to complete time’s inevitable circle.

My library allows me this unrealizable hope. But for the victims, of course, no reasons, literary or other, can excuse or expiate the deeds of their torturers. Nick Caistor, in his introduction to the English edition of Nunca más, the report on the “disappeared” during the Argentinian military dictatorship, reminds us that the stories that ultimately reach us are but the reports of the survivors. “One can only speculate,” says Caistor, “as to what accounts of atrocity the thousands of dead took with them to their unmarked graves.”271

It is difficult to understand how people continue to carry out the human gestures of everyday life when life itself has become inhuman; how, in the midst of starving and sickness, beatings and slaughter, men and women persist in civilized rituals of courtesy and kindness, inventing stratagems of survival for the sake of a speck of something loved, for one book rescued out of thousands, one reader out of tens of thousands, for a voice that will echo until the end of time the words of Job’s servant: “And I only am escaped alone to tell thee.” Throughout history, the victor’s library stands as an emblem of power, repository of the official version, but the version that haunts us is the other, the version in the library of ashes. The victim’s library, abandoned or destroyed, keeps on asking, “How were such acts possible?” My prayer book belongs to that questioning library.

After the European crusaders, following a forty-day siege, took the city of Jerusalem on 15 July, 1099, slaughtering the Muslim men, women and children and burning alive the entire Jewish community inside the locked synagogue, a handful of Arabs who had managed to escape arrived in Damascus, bringing with them the Koran of ’Uthman, one of the oldest existing copies of the holy book. They believed that their fate had been foretold in its pages (since God’s word must necessarily hold all past, present and future events), and that, if only they had been able to read the text clearly, they would have known the outcome of their own narrative.272 History was, for these readers, nothing but “the unfolding of God’s will for the world.”273 As our libraries teach us, books can sometimes help us phrase our questions, but they do not necessarily enable us to decipher the answers. Through reported voices and imagined stories, books merely allow us to remember what we have never suffered and have never known. The suffering itself belongs only to the victims. Every reader is, in this sense, an outsider.

Emerging from hell, travelling against Lethe’s current towards recollection, Dante carries with him the sounds of the suffering souls, but also the knowledge that those souls are being punished for their own avowed sins.274 The souls whose voices resound in our present are, unlike Dante’s damned, blameless. They were tortured and killed for no other reason than their existence, and maybe not even that. Evil requires no reason. How can we contain, between the covers of a book, a useful representation of something that, in its very essence, refuses to be contained, whether in Mann’s The Magic Mountain or in an ordinary prayer book? How can we, as readers, hope to hold in our hands the circle of the world and time, when the world will always exceed the margins of a page, and all we can witness is the moment defined by a paragraph or a verse, “choosing,” as Blake said, “forms of worship from poetic tales”? And so we return to the question of whether a book, any book, can serve its impossible purpose.

Portrait of Jacob Edelstein.

Perhaps. One day in June 1944, Jacob Edelstein, former elder of the Theresienstadt ghetto, who had been taken to Birkenau, was in his barracks, wrapped in his ritual shawl, saying the morning prayers he had learned long ago from a book no doubt similar to my Gebet-Ordnung. He had only just begun when SS Lieutenant Franz Hoessler entered the barracks to take Edelstein away. A fellow prisoner, Yossl Rosensaft, recalled the scene a year later:

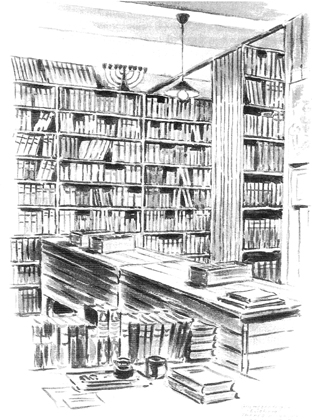

A sketch of the library in the Theresienstadt Ghetto, by Alfred Bergel, dated 27 November 1943.

Suddenly the door burst open and Hoessler strutted in, accompanied by three SS men. He called out Jacob’s name. Jacob did not move. Hoessler screamed: “I am waiting for you, hurry up!” Jacob turned round very slowly, faced Hoessler and said: “Of my last moments on this earth, allotted to me by the Almighty, I am the master, not you.” Whereupon he turned back to face the wall and finished his prayers. He then folded his prayer shawl unhurriedly, handed it to one of the inmates and said to Hoessler: “I am now ready.”275