If Night is the child of Chaos, then Lethe or Oblivion is its granddaughter, born of the terrible union between Night and Discord. In the sixth book of the Aeneid, Virgil imagines Lethe as a river whose waters allow the souls on their way to the underworld to forget their former selves, so that they can be born again.276 Lethe allows us oblivion of our former experience and happiness, but also of our prejudices and sorrows.

My library consists half of books I remember and half of books I have forgotten. Now that my memory is not as keen as it used to be, pages fade as I attempt to conjure them up. Some vanish from my experience entirely, unrecalled and invisible. Others haunt me temptingly with a title or an image, or a few words out of context. What novel begins with the words “One spring evening of 1890”? Where did I read that King Solomon used a looking-glass to discover whether the Queen of Sheba had hairy legs? Who wrote that peculiar book Flight into Darkness, from which I remember only the description of a blind corridor full of birds flapping their wings? In what story did I read the phrase “the lumber room of his library”? What volume showed a burning candle on the cover, with thick crayons on cream-coloured paper? Somewhere in my library are the answers to these questions, but I have forgotten where.

Visitors often ask if I’ve read all my books; my usual answer is that I’ve certainly opened every one of them. The fact is that a library, whatever its size, need not be read in its entirety to be useful; every reader profits from a fair balance between knowledge and ignorance, recall and oblivion. In 1930 Robert Musil imagined a devoted librarian who, working in Vienna’s Imperial Library, knows every single title in that gigantic assembly. “Do you want to know how I’ve been able to familiarize myself with every one of these books?” he asks an astonished visitor. “Nothing prevents me from telling you: it is because I read none of them!” And he adds, “The secret of every good librarian is never to read anything of all the literature with which he is entrusted, except the titles and the tables of contents. He who puts his nose inside the book itself is lost to the library! … Never will he be able to possess a view of the whole!” Hearing these words, Musil tells us, the visitor wants to do one of two things—either burst into tears or light a cigarette—but he knows that within the library walls both options are denied him.277

I have no feeling of guilt regarding the books I have not read and perhaps will never read; I know that my books have unlimited patience. They will wait for me till the end of my days. They don’t require that I pretend to know them all, nor do they urge me to become one of the “professional book-handlers” imagined by Flann O’Brien, who greedily collect books but do not read them, and who could (says O’Brien) earn their living “handling” books for a modest fee, making them look read, annotating the margins with forged comments and inscriptions, and even inserting theatre programs and other ephemera as bookmarks between the virgin leaves.278

Edward Gibbon, commenting on the voluminous library and crowded harem of the Roman emperor Gordian the Younger in the third century A.D., noted approvingly, “Twenty-two acknowledged concubines, and a library of sixty-two thousand volumes attested the variety of his inclinations; and from the productions which he left behind him, it appears that both the one and the other were designed for use rather than for ostentation.”279 Of course, no one except a mad prodigy would think of reading through a sixty-two-thousand-volume library, page after page, from Abbott to Zwingli, committing every book to memory, even if such a feat were possible. Gordian must have employed what Samuel Johnson, sixteen centuries later, called the cursory mode of reading. Johnson himself read with no method or discipline, sometimes leaving books uncut and following the text only where the pages fell open. “I do not suppose,” he said, “that what is in the pages that are closed is worse than what is in the open pages.” He never felt the obligation to read a book to the end or to start at the first page. “If a man begins to read in the middle of a book, and feels an inclination to go on, let him not quit it to go to the beginning. He may perhaps not feel again the inclination.” He thought it “strange advice” to urge someone to finish a book once started. “You may as well resolve that whatever men you happen to get acquainted with, you are to keep to them for life,” he argued. Nor would he necessarily seek out specific titles, but simply open whatever books he might come upon. Luck, he felt, was as good a counsellor as scholarship.

Johnson’s obsessive biographer, James Boswell, mentions that when Johnson was a boy, “having imagined that his brother had hid some apples behind a large folio upon an upper shelf in his father’s shop, he climbed up to search for them. There were no apples; but the large folio proved to be Petrarch, whom he had seen mentioned, in some preface, as one of the restorers of learning. His curiosity having been thus excited, he sat down with avidity, and read a great part of the book.” I am all too familiar with such happy encounters.

The forgotten volumes of my library lead a tacit, unobtrusive existence. And yet, their very quality of having been forgotten allows me, sometimes, to rediscover a certain story, a certain poem, as if it were utterly new. I open a book I think I have never opened before and come upon a splendid line that I tell myself I mustn’t forget, and then I close the book and see, on an endpaper, that my wiser, younger self marked that particular passage when he first discovered it at the age of twelve or thirteen. Lethe does not restore my innocence, but it allows me to be once more the boy who didn’t know who had murdered Roger Ackroyd, or who wept over the fate of Anna Karenina. I begin again at the first words, aware that I can’t truly begin again; I feel bereft of an experience that I know I’ve already had, and that I must acquire once more, like a second skin. In ancient Greece, the snake was Lethe’s symbol.

But there are libraries in which oblivion (or the attempt at oblivion) is sought precisely in order to discourage rediscovery. The already-mentioned censored libraries, the officious bureaucratic libraries, the scholarly libraries intent on documenting only that which academia considers to be true—all these belong to a dark and skulking breed. In an amusing book on the values of oblivion, the German scholar Harald Weinrich notes that a certain scientific frame of mind works along the lines of deliberate exclusion, so that, for instance, the library of scientific publications from which the Nobel Prize committee chooses its recipients is limited by the following four rules of enforced forgetting:

I. That which has been published in a language other than English … forget it.

II. That which has been published in a style different from that of the rewarded article … forget it.

III. That which has not been published in one of the prestigious magazines X, Y or Z … forget it.

IV. That which was published more than fifty years ago … forget it.280

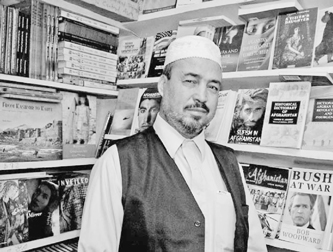

If reading is a craft that allows us to remember the common experience of humankind, it follows that totalitarian governments will try to suppress the memory held by the page. Under such circumstances, the reader’s struggle is against oblivion. After the bombing of Kabul in 2001, Shah Muhammad, a librarian–cum–bookseller who had survived various regimes of intolerance, described his experience to a journalist.281 He had opened his store thirty years earlier and had somehow managed to elude the executioners. His inspiration to resist for the sake of his books, he said, came from a verse by Firdausi, the celebrated tenth-century Persian poet, in The Book of Kings: “When facing a great danger, act sometimes as the wolf does, sometimes as the sheep.” Meekly Shah Muhammad bound his books in red during the dogmatic Communist regime, and pasted strips of paper over the images of living things during the iconoclastic reign of the Taliban. “But the communists burned my books…. And then the Taliban burned my books again.” Finally, during the last raid on his shop, while the police were piling his books on the pyre, Shah Muhammad abandoned his meek behaviour and went to see the minister of Culture. “You destroy my books,” he told him, “maybe you’ll destroy me, but there is something you’ll never destroy.” The minister asked what that might be. “The history of Afghanistan,” Shah Muhammad answered. Miraculously, he was spared.

The Afghan bookseller Shah Muhammad Rais in Kabul.

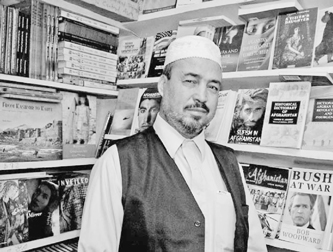

In the United States, attempts to curtail the reading of the black population date from the earliest days of slavery. In order to prevent slaves from rebelling, it was essential that they remain illiterate. If slaves learned to read, it was argued, they would become informed of political, philosophical and religious arguments in favour of abolition, and rise against their masters. Therefore, slaves who learned to read, even the Bible, were often punished with death; it was assumed that, while conversion of the slaves was “convenient,”282 knowledge of the Scriptures was to be acquired only through the eyes of their white masters. The black teacher Booker T. Washington noted that in his childhood “the great ambition of the older people was to try to learn to read the Bible before they died. With this end in view, men and women who were fifty and seventy-five years old, would be found in night-schools.”283

Not all whites believed that slaves learning to read would necessarily lead to an uprising; there were those who thought that, if they learned to read the Bible, they would become, on the contrary, meek and obedient servants. Even after the American Bible Society began to distribute Bibles to freed slaves in the late 1860s, there were those among free-thinking white educators who believed that education must serve not as a means to intellectual freedom, but “as an essential tool to moderate the threat arising from ‘an inferior, dangerous addition to the republic.’”284

BELOW: Portrait of Booker T. Washington.

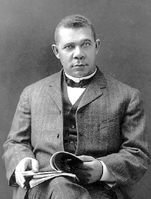

In the American South, libraries were not open to the black population until the early twentieth century. The first one recorded was the Cossitt Library in Memphis, Tennessee, which agreed to provide the LeMoyne Institute, a school for black children, with a librarian and a collection of books.285 In the Northern states, where public libraries had opened their doors to black readers a few years earlier, the fear of treading forbidden territory was still present as late as the 1950s. The young James Baldwin remembered standing at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Street, admiring “the stone lions that guarded the great main building of the Public Library.” The building seemed to him so vast that he had never yet dared enter it; he was terrified of losing himself in a maze of corridors and marble steps, and never finding the books he wanted. “And then everyone,” he wrote, as if observing himself from the distance of many years, “all the white people inside, would know that he was not used to great buildings, or to so many books, and they would look at him with pity.”286

A postcard showing the Cossitt Library in Memphis.

Oblivion can be forced on libraries in many ways—by the happenstances of war, or of displacement. In 1945, shortly before the end of the Second World War, a Russian officer discovered in an abandoned German train station a number of open crates overflowing with Russian books and papers that the Nazis had looted. This, according to the writer Ilya Ehrenburg, was all that was left of the celebrated Turgeniev Library, which the author of Fathers and Sons had founded in Paris in 1875 for the benefit of émigré students, and which the novelist Nina Berberova called “the greatest Russian library in exile.”287 And even those volumes have today vanished.

The Yiddish poet Rachel Korn, who spent most of her life, as she described it, “shipwrecked in Canada,” said that, after being exiled from her village in East Galicia, she felt like someone “being forced to leave your belongings on a sinking ship.” But she resisted what seemed to her “enforced oblivion.” “When you have been forced to leave your country,” she said, “every library is lost, except the ones you remember. And even those, you have to reread in your mind, over and over again, so that the pages don’t keep falling out.” Her daughter explained how, shortly after their arrival in Montreal, Korn had obliged her, every night, to go through the poems by Pushkin, by Akhmatova, by Mandelstam, that she had learned by heart, as if they were bedtime prayers. “Sometimes she corrected us and sometimes I corrected her.” Those remembered texts were the only library that counted for her in exile.288

Sometimes a library is wilfully allowed to vanish. In April 2003, the Anglo-American army stood by while the National Archives, the Archaeological Museum and the National Library of Baghdad were ransacked and looted. In a few hours, much of the earliest recorded history of humankind was lost to oblivion. The first surviving examples of writing, dating from six thousand years ago; medieval chronicles that had escaped the pillage of Saddam Hussein’s henchmen; numerous volumes of the exquisite collection of Korans kept at the Ministry of Religious Endowment—all disappeared, probably forever.289 Lost are the manuscripts lovingly penned by the illustrious Arab calligraphers, for whom the beauty of the script had to mirror the beauty of the contents. Vanished are collections of tales like those of the Arabian Nights, which the tenth-century Iraqi book dealer Ibn al-Nadim called evening stories because one was not supposed to waste the hours of the day reading trivial entertainment.290 The official documents that chronicled Baghdad’s Ottoman rulers have joined the ashes of their masters. Gone, finally, are the books that survived the Mongol conquest of 1258, when the invading army threw the contents of the libraries into the Tigris to build a bridge of paper that turned the waters black with ink.291 No one will ever again follow the years of correspondence that meticulously described dangerous voyages from the past and wonderful cities caught in time. And no one will again consult, in these particular copies, great reference works such as Dawn for the Night-Blind, by the fourteenth-century Egyptian scholar al-Qalqashandi, who, in one of the fourteen volumes, explained in detail how each of the letters of Arabic script should be formed, since he believed that what was written would never be forgotten.292

The looting of the National Library and State Archives of Baghdad.

Though a good number of objects were returned to Iraq in the months following the looting, by the end of 2004 a large proportion of the stolen books, documents and artifacts had not been recovered, in spite of the efforts of Interpol, UNESCO, ICOM (International Council of Museums) and several cultural agencies around the world. And many irreplaceable texts and objects were destroyed. “In all, what was recovered makes up less than 50 percent of what was stolen,” declared Dr. Donny George, director of the Baghdad Archeological Museum. “More than half of the looted material is still missing, which is a great loss for Iraq and for all of humanity.”293

Luciano Canfora has argued the importance of documenting not only the history of the disappearance of libraries and books, but the history of the awareness of their disappearance.294 He points out, for example, that in the first century B.C. Diodorus Siculus, commenting on the Greek philosopher Theopompus’s chronicles of the campaigns of Philip of Macedon, noted that the entire book consisted of fifty-eight volumes of which “unfortunately, five are no longer to be found.” Canfora explains that since Diodorus lived most of his life in Sicily, in regretting the loss of Theopompus’s five volumes he meant that they were absent from the local collections, probably from the historical library of Taormina. Eight centuries after Diodorus, however, the Byzantine patrician Photius, compiler of an encyclopedic bibliography under the title Bibliotheka, or Library, remarked, “We have read the Chronicles of Theopompus, of which only fifty-three volumes have survived.” The loss noticed by Diodorus was still true for Photius; that is to say, the awareness of the absence had become part of the work’s own history, counterbalancing, in some small measure, the oblivion to which the lost volumes had been condemned.

Stele with the Code of Hammurabi.

Trust in the survival of the word, like the urge to forget what words attempt to record, is as old as the first clay tablets stolen from the Baghdad Museum. To hold and transmit memory, to learn through the experience of others, to share knowledge of the world and of ourselves, are some of the powers (and dangers) that books confer upon us, and the reasons why we both treasure and fear them. Four thousand years ago, our ancestors in Mesopotamia already knew this. The Code of Hammurabi—a collection of laws inscribed on a tall, dark stone stele by King Hammurabi of Babylonia in the eighteenth century B.C., and preserved today in the Louvre Museum—offers us, in its epilogue, an enlightened example of what the written word can mean to the common man.

In order to prevent the powerful from oppressing the weak, in order to give justice to the orphans and widows … I have inscribed on my stele my precious words … If a man is sufficiently wise to maintain order in the land, may he heed the words I have written on this stele. … Let the oppressed citizen have the inscriptions read out…. The stele will illuminate his case for him. And as he will understand what to expect [from the words of the law], his heart will be set at ease.295