“It is as easy to dream up a book as it is difficult to put it on paper.”

Balzac, Le cabinet des antiques

There are two big sophora trees in my garden, just outside my library windows. During the summer, when friends are visiting, we sit and talk under them, sometimes during the day but usually at night. Inside the library, my books distract us from conversation and we are inclined to silence. But outside, under the stars, talk becomes less inhibited, wider ranging, strangely more stimulating. There is something about sitting outside in the dark that seems conducive to unfettered conversation. Darkness promotes speech. Light is silent—or, as Henry Fielding explains in Amelia, “Tace, madam, is Latin for a candle.”296

Tradition tells us that words, not light, came first out of the primordial darkness. According to a Talmudic legend, when God sat down to create the world, the twenty-two letters of the alphabet descended from his terrible and august crown and begged him to effect his creation through them. God consented. He allowed the alphabet to give birth to the heavens and the earth in darkness, and then to bring forth the first ray of light from the earth’s core, so that it might pierce the Holy Land and illuminate the entire universe.297 Light, what we take to be light, Sir Thomas Browne tells us, is only the shadow of God, in whose blinding radiance words are no longer possible.298 God’s backside was enough to dazzle Moses, who had to wait until he had returned to the darkness of the Sinai in order to read to his people their Lord’s commandments. Saint John, with praiseworthy economy, summed up the relationship between letters, light and darkness in one famous line: “In the beginning was the Word.”

Saint John’s sentence describes the reader’s experience. As anyone reading in a library knows, the words on the page call out for light. Darkness, words and light form a virtuous circle. Words bring light into being, and then mourn its passing. In the light we read, in the dark we talk. Urging his father not to allow himself to die, Dylan Thomas pressed now famous words on the old man: “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”299 And Othello too, in agony, confuses the light of candles with the light of life, and sees them as one and the same: “Put out the light,” he says, “and then put out the light.”300 Words call for light in order to be read, but light seems to oppose the spoken word. When Thomas Jefferson introduced the Argand lamp to New England in the mid-eighteenth century, it was observed that the conversation at dinner tables once lit by candlelight ceased to be as brilliant as before, because those who excelled in talking now took to their rooms to read.301 “I have too much light,” says the Buddha, refusing to say another word.302

In one other practical sense, words create light. The Mesopotamian who wished to continue his reading when night had fallen, the Roman who intended to pursue his documents after dinner, the monk in his cell and the scholar in his study after evening prayers, the courtier retiring to his bedchamber and the lady to her boudoir, the child hiding beneath the blankets to read after curfew—all set up the light necessary to illuminate their task. In the Archaeological Museum of Madrid stands an oil lamp from Pompeii by whose light Pliny the Elder may have read his last book, before setting off to die in the eruption of A.D. 79. Somewhere in Stratford, Ontario, is a solitary candleholder that dates back (its owner boasts) to Shakespeare’s time; it may once have held a candle whose brief life Macbeth saw as a reflection of his own. The lamps that guided Dante’s exiled reading in Ravenna and Racine’s cloistered reading in Port-Royal, Stendhal’s in Rome and De Quincey’s in London, all were born of words calling out from between their covers; all were light assisting the birth of light.

In the light, we read the inventions of others; in the darkness, we invent our own stories. Many times, under my two trees, I have sat with friends and described books that were never written. We have stuffed libraries with tales we never felt compelled to set down on paper. “To imagine the plot of a novel is a happy task,” Borges once said. “To actually write it is an exaggeration.”303 He enjoyed filling the spaces of the library he could not see with stories he never bothered to write, but for which he sometimes deigned to compose a preface, summary or review. Even as a young man, he said, the knowledge of his impending blindness had encouraged him in the habit of imagining complex volumes that would never take printed form. Borges had inherited from his father the disease that gradually, implacably weakened his sight, and the doctor had forbidden him to read in dim light. One day, on a train journey, he became so engrossed by a detective novel that he carried on reading, page after page, in the fading dusk. Shortly before his destination, the train entered a tunnel. When it emerged, Borges could no longer see anything except a coloured haze, the “darkness visible” that Milton thought was hell. In that darkness Borges lived for the rest of his life, remembering or imagining stories, rebuilding in his mind the National Library of Buenos Aires or his own restricted library at home. In the light of the first half of his life, he wrote and read silently; in the gloom of the second, he dictated and had others read to him.

In 1955, shortly after the military coup that overthrew the dictatorship of General Perón, Borges was offered the post of director of the National Library. The idea had come from Victoria Ocampo, the formidable editor of Sur magazine and Borges’s friend for many years. Borges thought it “a wild scheme” to appoint a blind man as librarian, but then recalled that, oddly enough, two of the previous directors had also been blind: José Mármol and Paul Groussac. When the possibility of the appointment was put forward, Borges’s mother suggested that they take a walk to the library and look at the building, but Borges felt superstitious and refused. “Not until I get the job,”304 he said. A few days later, he was appointed. To celebrate the occasion, he wrote a poem about “the splendid irony of God” that had simultaneously granted him “books and the night.”305

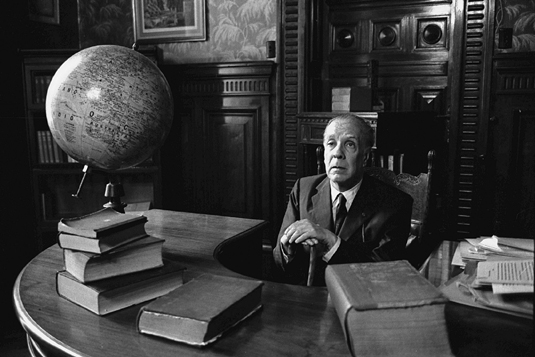

Jorge Luis Borges at his desk in the Buenos Aires National Library.

Borges worked at the National Library for eighteen years, until his retirement, and he enjoyed his post so much that he celebrated almost every one of his birthdays there. In his wood-panelled office, under a high ceiling studded with painted fleurs-de-lys and golden stars, he would sit for hours at a small table, his back towards the room’s centrepiece—a magnificent, huge round desk, a copy of one that had belonged to the Prime Minister of France, Georges Clemenceau, that Borges felt was far too ostentatious. Here he dictated his poems and fictions, had books read to him by willing secretaries, received friends, students and journalists, and held study groups of Anglo-Saxon. The tedious, bureaucratic library work was left to his assistant director, the scholar José Edmundo Clemente.

Many of Borges’s published stories and essays mention books that he invented without bothering to write them out. Among these are the many romances by the fictional Herbert Quain (the subject of an essaylike fiction), who varies one single plot in geometrical progression until the number of plots becomes infinite; the marvellous detective novel The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim, by “the Bombay lawyer Mir Bahadur Ali,” supposedly reviewed by the very real Philip Guedalla and Cecil Roberts, and published by the equally real Victor Gollancz in London, with an introduction by Dorothy L. Sayers, under the revised title The Conversation with the Man Called Al-Mu’tasim: A Game with Shifting Mirrors; the eleventh volume of the First Encyclopaedia of Tlön, which Herbert Ashe received, shortly before his death, in a sealed and registered parcel from Brazil; the play The Enemies, which Jaromir Hladik left unfinished but was allowed to complete in his mind in a long, God-granted instant before his execution; and the octavo volume of infinite pages, bearing the words “Holy Writ” and “Bombay” on its spine, that (Borges tells us) he held in his hands shortly before retiring from his post as director of the National Library.306

The collecting of imaginary books is an ancient occupation. In 1532 there appeared in France a book signed by the apocryphal scholar Alcofribas Nasier (an anagram of François Rabelais) entitled The horrible and frightening deeds and accomplishments of the much renowned Pantagruel, King of the Dipsods, son of the great giant Gargantua.307 In the seventh chapter of the second book, the young Pantagruel, having studied “very well” at Orléans, resolves to visit Paris and its university. It is, however, not the learned institution but the Abbey of St. Victor that holds his attention, for there he finds “a very stately and magnifick” library full of the most wonderful books. The catalogue that Rabelais copies for us is five pages long, and includes such marvels as:

The Giant Gargantua created by François Rabelais.

The Codpiece of the Law

The Pomegranate of Vice

The mustard-pot of Penance

The Trevet of good thoughts

The Snatchfare of the Curats

The Spectacles of Pilgrims bound for Rome

The Fured Cat of the Sollicitors and Atturneys

The said Authors Apologie against those who alledge that the Popes mule doth eat but at set times

The bald arse or peel’d breech of the widows

The hotchpot of Hypocrites

The bumsquibcracker of Apothecaries

The Mirrour of basenesse by Radnecu Waldenses

The fat belly of the Presidents

In a letter of advice sent to his son from Utopia, Gargantua encourages Pantagruel to make good use of his skills “by which we may in a mortal estate attain to a kinde of immortality.” “All the world is full of knowing men,” he writes, “of most learned Schoolmasters, and vast Libraries: and it appears to me as a truth, that neither in Plato’s time, nor Cicero’s, nor Papinian’s, there was ever such conveniency for studying, as we see at this day there is. … I see robbers, hangmen, freebooters, tapsters, ostlers, and such like, of the very rubbish of the people, more learned now, than the Doctors and Preachers were in my time.” The library that Rabelais invents is perhaps the first “imaginary library” in literature. It mocks (in the tradition of his admired Erasmus and Thomas More) the scholarly and monastic world, but, more important, allows the reader the fun of imagining the arguments and plots behind the rollicking titles. On another of his Gargantuan abbeys, that of Thelême, Rabelais inscribed the motto Fays ce que voudra (Do As You Please). On his library at St. Victor he might have written Lys ce que voudra (Read As You Please). I’ve written those words over one of the doors of my own library. Rabelais was born in 1483 or 1484, near the town of Chinon, not far from where I now live. His house was called La Devinière, or The Soothsayer’s House; its original name had been Les Cravandières, after cravant, meaning “wild goose” in the Touraine dialect. Since geese were used to predict the future, the house’s name was changed to honour the birds’ magical gift.308 The house, the landscape around it, the towns and monuments even as far as the thin eleventh-century tower of Marmande that I can see from the end of my garden, became the setting for his gigantic saga. The success of Pantagruel (over four thousand copies sold in the first few months) made Rabelais decide to continue the adventures of his giants. Two years later he published The Very Horrific Life of the Great Gargantua, Father of Pantagruel, and several other volumes of the saga. In 1543 the Church banned Rabelais’ books, and published an official edict condemning his work.

Rabelais could read Latin, Greek, Italian, Hebrew, Arabic and several dialects of French; he had studied theology, law, medicine, architecture, botany, archaeology and astronomy; he enriched the French language with more than eight hundred words and dozens of idioms, many of which are still used in Acadian Canada.309 His imaginary library is the fruit of a mind too active to stop and record its thoughts, and his Gargantuan epic is a hodgepodge of episodes that allows the reader almost any choice of sequence, meaning, tone and even argument. It is as if, for Rabelais, the inventor of a narrative is not obliged to bring coherence, logic or resolution to the text. That (as Diderot would later make clear) is the task of the reader, the mark of his freedom. The ancient scholastic libraries took for granted the truth of the traditional commentaries on the classics; Rabelais, like his fellow humanists, questioned the assumption that authority equalled intelligence. “Knowledge without conscience,” says Gargantua to his son, “is but the ruin of the soul.”

The historian Lucien Febvre, in a study of the religious beliefs in Rabelais’ time, attempted to describe the writer in sixteenth-century terms. “What was Rabelais like mentally? Something of a buffoon … boozing his fill and in the evening writing obscenities? Or perhaps a learned physician, a humanist scholar who filled his prodigious memory with beautiful passages from the ancients … ? Or, better yet, a great philosopher, acclaimed as such by the likes of Theodore Beza and Louis Le Caron?” Febvre asks, and concludes, “Our ancestors were more fortunate than we are. They did not choose between two images. They accepted them both at the same time, the respectable one along with the other.”310

Rabelais’ House in Chinon, France.

Rabelais was able to maintain simultaneously both a questioning spirit, and faith in what he saw as the established truth. He needed to probe the assertions of fools, and to judge for himself the weight of truisms. The books he read as a scholar, full of the wisdom of the ancients, must have been balanced in his mind by the questions left unanswered and the treatises never written. His own library of parchment and paper was grounded by his imaginary library of forgotten or neglected subjects of study and reflection. We know what books (real books) he carried in his “portable library,” a chestful that accompanied him throughout the twenty years of his wanderings in Europe. The list—which left him in constant peril of the Inquisition—included Hippocrates’ Aphorisms, the works of Plato, Seneca and Lucian, Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly and More’s Utopia, and even a dangerous recently published Polish book, the De revolutionibus of Copernicus.311 The books he invented for Pantagruel are their irreverent but tacit gloss.

The critic Mikhail Bahktin has pointed out that Rabelais’ imaginary books have their antecedent in the parodic liturgies and comic gospels of earlier centuries. “The medieval parody,” he says, “intends to describe only the negative or imperfect aspects of religion, ecclesiastical organization and scholarly science. For these parodists, everything, without exception, is humorous; laughter is as universal as seriousness, and encompasses the whole of the universe, history, society and conception of the world. Theirs is an all-embracing vision of the world.”312

Rabelais’ Gargantua was succeeded by a number of imitations in the following century. Most popular among these were a series of catalogues of imaginary libraries published (largely as political satires) in England during the Civil War, such as the Bibliotheca Parliamenti of 1653, attributed to Sir John Birkenhead, which included such irreverent titles as Theopoeia, a discourse shewing to us mortals, that Cromwel may be reckoned amongst the gods, since he hath put off all humanity.313 In that same year Sir Thomas Urquhart published the first English translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel, and the learned Sir Thomas Browne composed, in imitation of Rabelais, a tract he called Musaeum Clausum, or, Bibliotheca abscondita: containing some remarkable Books, Antiquities, Pictures and Rarities of several kinds, scarce or never seen by any man now living. In this “Closed Museum or Hidden Library” are many strange volumes and curious objects: among them an unknown poem written in Greek by Ovid during his exile in Tomis, a letter from Cicero describing the Isle of Britain, a relation of Hannibal’s march from Spain to Italy, a treatise on dreams by King Mithridates, an eight-year-old girl’s miraculous collection of writings in Hebrew, Greek and Latin, and a Spanish translation of the works of Confucius. Among pictures of “rare objects” Sir Thomas lists “An handsome Piece of Deformity expressed in a notable hard Face” and “An Elephant dancing upon the Ropes with a Negro Dwarf upon his Back.”314 The clear intention is to mock the popular beliefs of the day, but the result is slightly stilted and far less humorous than its model. Even imaginary libraries can sink under the prestige and pompousness of academia.

In one instance both the library space and the book titles were visible, yet the books represented were imaginary. At Gad’s Hill (the house he dreamed of as a child, which he managed to buy twelve years before his death in 1870), Charles Dickens assembled a copious library. A door in the wall was hidden behind a panel lined with several rows of false book spines. On these spines Dickens playfully inscribed the titles of apocryphal works of all sorts: Volumes I to XIX of Hansard’s Guide to Refreshing Sleep, Shelley’s Oysters, Modern Warfare by General Tom Thumb (a famous Victorian circus dwarf), a handbook by the notoriously henpecked Socrates on the subject of wedlock, and a ten-volume Catalogue of Statues to the Duke of Wellington.315

A wood-carving by Gwen Raverat depicting Sir Thomas Browne inspired by Death.

Colette, in one of the books of memoirs with which she delighted in scandalizing her readers in the thirties and forties, tells the story of imaginary catalogues compiled by her friend Paul Masson—a ex–colonial magistrate who worked at the Bibliothèque Nationale, and an eccentric who ended his life by standing on the edge of the Rhine, stuffing cotton wool soaked in ether up his nose and, after losing consciousness, drowning in barely a foot of water. According to Colette, Masson would visit her at her seaside villa and pull from his pockets a portable desktop, a fountain pen and a small pack of blank cards. “What are you doing?” she asked him one day. “I’m working,” he answered. “I’m working at my job. I’ve been appointed to the catalogue section of the Bibliothèque Nationale. I’m making an inventory of titles.” “Oh, can you do that from memory?” she marvelled. “From memory? What would be the merit? I’m doing better. I’ve realized that the Nationale is poor in Latin and Italian books from the fifteenth century,” he explained. “Until chance and erudition fill the gaps, I am listing the titles of extremely interesting works that should have been written…. At least these titles may save the prestige of the catalogue….” “But if the books don’t exist … ?” “Well,” Masson answered with a frivolous gesture, “I can’t be expected to do everything!”316

Charles Dickens in his library in Gad’s Hill.

Portrait of Paul Maison.

Libraries of imaginary books delight us because they allow us the pleasure of creation without the effort of research and writing. But they are also doubly disturbing—first because they cannot be collected, and secondly because they cannot be read. These promising treasures must remain closed to all readers. Every one of them can claim the title Kipling gives to the never-to-be-written tale of the young bank clerk Charlie Mears, “The Finest Story in the World.”317 And yet the hunt for such imaginary books, though necessarily fruitless, remains compelling. What devotee of horror stories has not dreamt of coming upon a copy of the Necronomicon,318 the demonic manual invented by H.P. Lovecraft in his dark Cthulhu saga? According to Lovecraft, the Al Azif (to give it its original title) was written by Abdul Alhazred c. 730 in Damascus. In 950 it was translated into Greek under the title Necronomicon by Theodorus Philetas, but the sole copy was burnt by the Patriarch Michael in 1050. In 1228 Olaus translated the original (now lost) into Latin.319 A copy of the Latin work is supposedly kept in the library of Miskatonic University in Arkham, “one well known for certain forbidden manuscripts and books gradually accumulated over a period of centuries and begun in colonial times.” Other than the Necronomicon, these forbidden works include “the Unaussprechlichen Kulten of von Junzt, the Comte d’Erlette’s Cultes des Goules, Ludvig Prinn’s De Vermiis Mysteriis, the R’lyeh Text, the Seven Cryptical Books of Hsan, the Dhol Chants, the Liber Ivoris, the Celaeno Fragments, and many other, similar texts, some of which exist only in fragmentary form, scattered over the globe.”320

Not all imaginary libraries contain imaginary books. The library that the barber and the priest condemn to the flames in the first part of Don Quixote; Mr. Casaubon’s scholarly library in George Eliot’s Middlemarch; Des Esseintes’s languorous library in Huysmans’ A rebours; the murderous monastic library in Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose … all these are merely wishful. Given money enough and time, such dream libraries could find a solid reality. The library that Captain Nemo shows Professor Aronnax in Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea (with the exception of two books by Aronnax himself, of which only one is given a title, Les grands fonds sous-marins) is one that any wealthy French literary gentleman of the mid-nineteenth century might have acquired. “Here are,” says Captain Nemo, “the major works of the ancient and modern masters, that is to say, all the most beautiful creations of humanity in the realms of history, poetry, fiction and science, from Homer to Victor Hugo, from Xenophon to Michelet, from Rabelais to Madame Sand.”321 All real books.

Like their brethren of solid wood and paper, not all imaginary libraries are composed only of books. Captain Nemo’s treasure trove is enriched by two further collections, one of paintings and one of “curiosities,” according to the custom of European scholars of his time. The duke’s wilderness library in As You Like It, made up of “tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in every thing,”322 requires no volumes of paper and ink. Pinocchio, in the nineteenth chapter of Collodi’s novel, tries to imagine what he might do if he had a hundred thousand coins and were a wealthy gentleman, and wishes for a beautiful palace with a library “crammed full with candied fruit, cakes, panettoni, almond biscuits and wafers stuffed with cream.”323

The distinction between libraries that have no material existence, and those with books and papers that we can hold in our hand, is sometimes strangely blurred. There exist real libraries with solid volumes that seem imaginary, because they are born from what Coleridge famously called the voluntary suspension of disbelief. Among them stands the Father Christmas Library in the Provincial Archives of Oulu, Northern Finland, whose other, more conventional holdings go back to the sixteenth century. Since 1950 the Finnish Post’s “Santa Claus Postal Service” has been in charge of replying to about six hundred thousand letters received yearly from more than one hundred and eighty countries. Until 1996 the letters were destroyed after being answered, but since 1998 an agreement between the Finnish Postal Services and the provincial authorities has allowed the Oulu Archives to select and preserve a number of the letters received every December, mainly, but not exclusively, from children. Oulu was chosen because, according to Finnish tradition, Father Christmas lives on Korvantunturi, or Ear Mountain, located in that district.324

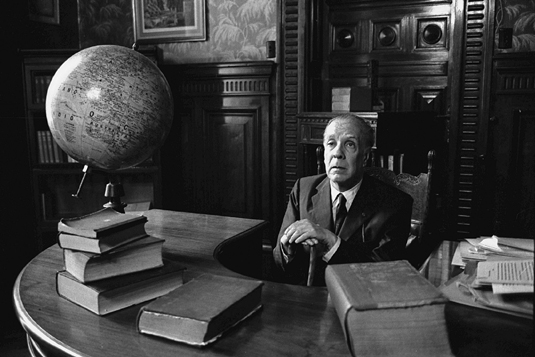

Captain Nemo’s library, an illustration from the first edition of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

Other libraries deserve to be imaginary for more whimsical reasons—such as the Doulos Evangelical Library, housed in the oldest-serving ocean liner, which tours the world with a cargo of half a million books and a staff of three hundred people; and the minuscule library of Geneytouse, in southwestern France, perhaps the smallest library in the world, lodged in a hut of nine square metres, without water, heating or electricity, founded by Etienne Dumont Saint-Priest, a local farmer passionate about literature and music, who had long dreamt of offering his village a place to read and exchange books.

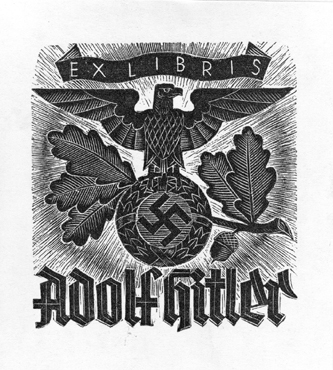

But not all our libraries come from dreams; some belong to the realm of nightmares. In the spring of 1945, a group of American soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division discovered, hidden in a salt mine near Berchtesgaden, the remains of the library of Adolf Hitler, “haphazardly stashed in schnapps crates with the Reich Chancellery address on them.”325 Of the grotesque collection, only twelve hundred, bearing either the Führer’s bookplate or his name, were deemed worth preserving in the Library of Congress in Washington, on the third floor of the Jefferson Building. According to the journalist Timothy W. Ryback, these spoils of war have been curiously overlooked by historians of the Third Reich. Hitler’s original library has been estimated at sixteen thousand volumes, of which about seven thousand were on military history, over a thousand were essays on the arts, almost a thousand were works of popular fiction, several more were tracts of Christian spirituality and a few were pornographic stories. Only a handful of classic novels were included: Gulliver’s Travels, Robinson Crusoe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Don Quixote, as well as most of the adventure stories by Hitler’s favourite author, Karl May. Among the volumes kept in the Library of Congress are a French vegetarian cookbook inscribed by its author, Maïa Charpentier, to Monsieur Hitler, végétarien, and a 1932 treatise on chemical warfare explaining the uses of prussic acid, later commercialized as Zyklon B. It is difficult to think of constructing, with any hideous accuracy, a portrait of this library’s owner. Let there be libraries that the imagination condemns simply because of the reputation of their reader.

Hitler’s personal bookplate.

We lend libraries the qualities of our hopes and nightmares; we believe we understand libraries conjured up from the shadows; we think of books that we feel should exist for our pleasure, and undertake the task of inventing them unconcerned about any threat of inaccuracy or foolishness, any terror of writer’s cramp or writer’s block, any constraints of time and space. The books dreamt up through the ages by raconteurs thus unencumbered compose a much vaster library than those resulting from the invention of the printing press—perhaps because the realm of imaginary books allows for the possibility of one book, as yet unwritten, that escapes all the blunders and imperfections to which we know we are condemned. In the dark, under my two trees, my friends and I have shamelessly added to the catalogues of Alexandria entire shelves full of perfect volumes that disappeared without trace by morning.