I keep a list of books that I feel are missing from my library and that I hope one day to buy, and another, more wishful than useful, of books I’d like to have but I don’t even know exist. In this second list are A Universal History of Ghosts, A Description of Life in the Libraries of Greece and Rome, a third Dorothy L. Sayers detective novel completed by Jill Paton Walsh, Chesterton on Shakespeare, a Summary of Averroës on Aristotle, a literary cookbook that draws its recipes from fictional descriptions of food, a translation of Calderón’s Life Is a Dream by Anne Michaels (whose style, I feel, would suit Calderón’s admirably), a History of Gossip, the True and Uncensored Memoirs of a Publishing Life by Louise Dennys, a well-researched, well-written biography of Borges, an account of what exactly happened during Cervantes’s captivity in Algiers, an as-yet-unpublished novel by Joseph Conrad, the diary of Kafka’s Milena.

We can imagine the books we’d like to read, even if they have not yet been written, and we can imagine libraries full of books we would like to possess, even if they are well beyond our reach, because we enjoy dreaming up a library that reflects every one of our interests and every one of our foibles—a library that, in its variety and complexity, fully reflects the reader we are. It is therefore not unreasonable to suppose that, in a similar fashion, the identity of a society, or a national identity, can be mirrored by a library, by an assembly of titles that, practically and symbolically, serves as our collective definition.

It was probably Petrarch who first imagined that a public library should be funded by the state.326 In 1326, after the death of his father, he abandoned his legal studies and entered the Church as a means of pursuing a career in literature, which eventually culminated in his being crowned poet laureate on the Campidoglio in Rome in 1341. During the following years he divided his time between Italy and the south of France, writing and collecting books, and acquiring an unparalleled scholarly reputation. In 1353, tired of the squabbles at the papal court at Avignon, Petrarch settled for a time in Milan, then in Padua and finally in Venice. Here he was welcomed by the chancellor of the republic, who in 1362 obtained for him a palazzo on the Riva degli Schiavoni in return for the bequest of his by now celebrated library.327 Petrarch agreed on condition that his books be “perfectly preserved … in some fire- and rain-proof location to be assigned for this purpose.” Though he modestly stated that his books were neither numerous nor very valuable, he expressed the hope that “this glorious city will add other books at public expense, and that also private individuals … will follow the example. … In this fashion it might easily be possible to establish a large and famous library, equal to those of antiquity.”328 His wish was granted several times over. Instead of one national library, Italy boasts eight, two of which (those in Florence and in Rome) act jointly as the central library of the nation.

In Britain, the notion of a national library was late in developing. After the dispersal of the libraries following the dissolution of the monasteries ordered by Henry viii, in 1556 the mathematician and astrologer John Dee, himself the owner of a remarkable collection of books, suggested to Henry’s daughter Queen Mary the establishment of a national library that might collect the manuscripts and books “of ancient writers.” The proposal was ignored, though repeated during the following reign of Elizabeth I by the Society of Antiquaries. A third plan was presented to her successor, James i, who showed himself agreeable to the idea but died before it could be put into practice. His son, Charles i, had no interest in the matter, despite the fact that royal librarians were routinely appointed during his reign to look after the haphazard royal collections, though with little inclination or success.

Then in 1694, during the reign of William iii, the classical scholar Richard Bentley was appointed to the post of keeper of the royal books. Shocked by the sorry state of the library, Bentley published, three years later, A proposal for building a Royal Library and establishing it by Act of Parliament, in which he suggested that a new edifice should be erected in St. James’s Park for the specific purpose of housing books, and that it should receive an annual grant from Parliament. Though his urging received no answer, Bentley’s devotion to the nation’s books never ceased. In 1731, when a fire broke out one night in the Cotton Collection (which contained, in addition to the already mentioned Lindisfarne Gospels, two of the earliest manuscripts of the New Testament, the Codex Sinaiticus of the mid-fourth century and the Codex Alexandrinus of the early fifth century), the royal librarian was seen running out into the street “in wig and night-dress, with the Codex Alexandrinus under his arm.”329

As a result of Bentley’s proposal, in 1739 Parliament acquired the magnificent books and objects left by Sir Hans Sloane on his death, and later, in 1753, Montagu House in Bloomsbury, to store them. The house had been designed by an architect from Marseilles in the so-called French style, after the first Montagu House had burnt down in 1686, only a few years after its construction, and possessed many rooms suitable for the display of Sloane’s treasures, as well as several acres of fine gardens for visitors to stroll in.330 A few years later, George II donated his royal book collection to the library—which was by then called the British Museum. On 15 January 1759, the British Library at the Museum opened its impressive doors. At the king’s request, the contents were made available to the general public. “Tho’ chiefly designed for the use of learned and studious men, both native and foreigners, in their researches into several parts of knowledge, yet being a national establishment … the advantages accruing from it should be rendered as general as possible.” During its early years, however, the librarians’ main task was not to compile catalogues and seek new titles, but to guide visitors around the museum’s collections.331

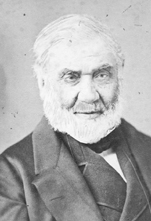

Portrait of Sir Antonio Panizzi.

The hero of the British Library saga is the Italian-born Antonio Panizzi, mentioned previously with regard to the shape of the Reading Room. Threatened with arrest in Italy for being a member of the secret carbonari, who opposed Napoleonic rule, the twenty-five-year-old revolutionary had fled to the safety of England. After a brief period as a teacher of Italian, he was named assistant librarian at the British Museum in 1831. A year later he became a British citizen, changing his name to Anthony.

Like his compatriot Petrarch, Panizzi felt that it was the state’s responsibility to fund a national library for the benefit of everyone. “I want,” he said in a report dated 14 July, 1836, “a poor student to have the same means of indulging his learned curiosity, of following his rational pursuits, of consulting the same authorities, of fathoming the most intricate inquiry, as the richest man in the Kingdom, as far as books go, and I contend that Government is bound to give him the most liberal and unlimited assistance in this respect.”332 In 1856 Panizzi ascended to the post of principal librarian, and through his keen intellectual gifts and his administrative abilities he transformed the institution into one of the world’s greatest cultural centres.333

To achieve his goal, Panizzi planned and started the library’s catalogue; he enforced the 1842 Copyright Act, which required that a copy of every book printed in Great Britain be deposited in the library; he successfully lobbied for an increase in government funds; and by insisting that the staff be recognized as civil servants he greatly bettered the librarians’ working conditions, which must have been infernal. The biographer and essayist Edmund Gosse, a good friend of Swinburne, Stevenson and Henry James, was employed in the library in the late 1860s as “one of the humblest of mankind, a Junior Assistant in the Printed Books Department.” He described his working space, shortly before Panizzi’s improvements, as an overheated, “singularly horrible underground cage, made of steel bars, called the Den … a place such as no responsible being is allowed to live in nowadays, where the transcribers on the British Museum staff were immured in a half-light.”334

Panizzi (Gosse depicted him as a “dark little old Italian, sitting like a spider in a web of books”)335 wanted the British Museum library to be one of the finest, best-run libraries in the world, but above all he wanted the “web of books” to be the stronghold of British cultural and political identity. He outlined his vision in the clearest possible terms:

1st. The attention of the Keeper of the emphatically British library ought to be directed most particularly to British works and to works relating to the British Empire; its religious, political and literary as well as scientific history; its laws, institutions, descriptions, commerce, arts, etc. The rarer and more expensive a work of this description is, the more reasonable efforts ought to be made to secure it for the library.

2ndly. The old and rare, as well as the critical editions of ancient classics, ought never to be sought for in vain in this collection; nor ought good comments, as also the best translations into modern languages be wanting.

3rdly. With respect to foreign literature, arts and sciences, the library ought to possess the best editions of standard works for critical purposes or for use. The public have, moreover, a right to find in their national library heavy, as well as expensive, foreign works, such as literary journals, transactions of societies, large collections, historical or otherwise, complete series of newspapers, and collections of law and their best interpreters.336

Panizzi saw the British national library as a portrait of the national soul. Foreign literature and cultural material were to be collected (he posted agents for this purpose in Germany and in the United States), but mainly for comparison and reference, or to complete a collection. What mattered to Panizzi was that every aspect of British life and thought be represented, so that the library could become a showcase of the nation itself. He was clear as to what a national library should stand for; less obvious was, to his mind, the manner in which it should be used. Since even a national library’s capacity to accommodate readers is limited, should such an institution be only one of last resort? Thomas Carlyle complained that every Tom, Dick and Harry used the library for purposes totally unconnected with scholarship and study. “I believe,” he wrote, “there are several people in a state of imbecility who come to read in the British Museum. I have been informed that there are several in that state who are sent there by their friends to pass away the time.”337

Panizzi wanted the library always to be available to every “poor student” wishing to indulge “his learned curiosity.” For practical reasons, however, should a national library be available only to those readers (students or otherwise) who have failed to find the books they need in other public libraries? Should it provide ordinary services to the common reader, or should it function solely as an archive of last resort, holding that which, because of its rarity or uniqueness, cannot be distributed more broadly? Up to 2004 the British Library delivered reader’s cards only to those who could prove that the books they were looking for were not available elsewhere, and even then, only to researchers who could provide evidence of their status through letters of reference. Commenting on the “accessibility” program that eliminated this requirement that one be a “researcher,” in September 2005 a reader unwittingly echoed Carlyle’s complaint: “Every day the library is filled with, among others, people sleeping, students doing their homework, bright young things writing film scripts—in fact, doing almost anything except consulting the library’s books.”338

The ultimate function of a national library is still in question. Today, electronic technology can open a national library to most readers in their own homes, and even provide cross-library services; not only is the reading space extended well beyond the library’s walls, but the books themselves mingle with and complement the holdings of other libraries. For example: I wish to consult a book on the intriguing subject of mermaid mythology, Les Sirènes by Georges Kastner, published in Paris in 1858. I discover that the large municipal library of Poitiers does not possess a copy. My librarian kindly offers to search for the nearest library that might hold one, and discovers (thanks to the electronic cataloguing system) that the only copy in France is at the Bibliothèque Nationale. Because of its rarity, the book cannot be lent out, but it can be photocopied. The Poitiers library can request that a complete, bound photocopy be made which will enter their holdings, so that I am able to borrow it. The system, though not perfect, allows me access to some of the rarest books in the national holdings—and even beyond, in the stacks of other countries bound by inter-library agreements.

Since Les Sirènes is an old book and not covered by the laws of copyright, it could have been scanned and entered into one of the virtual library systems, so that I could download and print it myself or, for a fee, commission a printing from a server. This seemingly new system echoes one established centuries ago by medieval universities, in which a text recommended by a teacher could be copied by scribes who set up shop outside the university walls and sold their services to the students. In order to preserve, as far as possible, the accuracy of classical texts, university authorities devised an ingenious method. Carefully checked manuscripts were lent to “stationers” who, for a fixed tariff or tax, sent them out to be copied, either to obtain texts to sell themselves, or to rent to students too poor to commission copies, who were therefore forced to do the work themselves. The original text (an exemplar) did not go out as a single book, but in sections (peciae) that were returned to the stationer after being copied; he could then rent them out once again. When the first printing presses were installed, university authorities considered them nothing more than a useful means of producing copies with a little more speed and accuracy.339

Lebanon is a country that boasts at least a dozen different religions and cultures. Its national library is a recent acquisition, dating only to 1921, when Viscount Philippe de Tarazi, a Lebanese historian and bibliophile, donated his collection to the state with the precise instructions that it become “the core of what should become the Great Library of Beyrouth.” De Tarazi’s donation comprised twenty thousand printed volumes, a number of precious manuscripts and the first issues of national newspapers. Three years later, in order to augment the collection, a government decree established a legal deposit system (requiring that a copy of every book printed in the country be submitted), and staffed the library with eight clerks under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education. During the civil war that ravaged the country from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s, the National Library was many times bombed and looted. In 1979, after four years of fighting, the government closed the facilities and stored the surviving manuscripts and documents in the vaults of the National Archives. Modern printed books were stored in a separate building between 1982 and 1983, but this site was also heavily bombed, and the books spared by gunfire were damaged by rainwater and insect infestation. At last, after the war ended, and with the assistance of a group of experts from the French Bibliothèque Nationale, plans were drawn up in 1994 to re-establish the surviving collections in a new site.

Visiting Lebanon’s rescued books is a melancholy experience. It is obvious that Lebanon still requires much assistance to disinfect, restore, catalogue and put away its collection. The works are stacked in modern rooms in a customs building too near the sea to prevent dampness. A handful of clerks and volunteers page through the piles of print and place the books on shelves; an expert eye will determine which are worth restoring and which must be discarded. In another building, a librarian specializing in ancient texts sifts through the Oriental manuscripts, some dating from the ninth century, in order to grade the severity of the deterioration, marking each piece with a coloured label, from red (the worst condition) to white (requiring minor repairs). But it is obvious that neither the staff nor the funding suffices for the enormous task.

But there is a hopeful side. A now vacant building that used to house the Faculty of Law of the Lebanese University in Beyrouth has been designated the home of the new National Library, and should soon be open to the public. In her report on the project, read out in May 2004, Professor Maud Stéphan-Hachem, advisor to the minister of Culture, pointed out that the library might in fact “help reconcile a plural reality,” reweaving all of Lebanon’s cultural strands.

The project of a national library for Lebanon has always been defended, supported and favoured by all our intellectual bibliophiles, but up to now each one of them appropriated the project for himself, lending it his own dreams and his own personal vision of our much embattled culture. It could however become a project of the whole of our society, a public project in which the entire state must have a hand, especially because of its eminently political dimension. It should not be reduced to a mere saving of books, or to the rebuilding of an institution modelled on other such libraries in the world. It is a political project of Lebanese reconciliation, preserving the memory both of the recognition of others, effected concretely through inventories and recordings, and of the recognition of the value of their works.340

The books of the Lebanon National Library in precarious storage.

Can a library reflect a plurality of identities? My own library—set up in a small French village to which it has no visible connection, and made up of fragmentary libraries collected in Argentina, England, Italy, France, Tahiti and Canada during the course of a peripatetic life—proclaims a number of changing identities. I am, in a sense, the library’s only citizen, and can therefore claim common bonds with its holdings. And yet many friends have felt that the identity of this ragbag library was at least partly theirs as well. It may be that, because of its kaleidoscopic quality, any library, however personal, offers to whoever explores it a reflection of what he or she seeks, a tantalizing wisp of intuition of who we are as readers, a glimpse into the secret aspects of the self.

Immigrants sometimes gravitate to libraries to learn more about their country of adoption, not only its history and geography and literature, its dates and maps and national poems, but also a general understanding of how the country thinks and organizes itself, how it divides and catalogues the world—a world that includes the immigrant’s past. Queens Borough Public Library in New York is the busiest library in the United States, circulating over fifteen million books, tapes and videos a year—mainly to an immigrant population, since nearly half the residents of Queens speak a language other than English at home, and more than a third were born in a foreign country. The librarians speak Russian, Hindi, Chinese, Korean, Gujarati and Spanish, and can explain to their new readers how to get a driver’s licence or navigate the Internet and learn English. The most sought-after titles are translations of American potboilers into the immigrants’ own languages.341 Queens may not be the cultural repository that Panizzi had in mind for a nation, but it has become one of many libraries that hold up a mirror to the pluralistic, vertiginous, challenging identity of the country and the times.