In 1972, the president of Blue Chip Stamp, a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary, contacted Warren Buffett to let him know that See’s Candies was for sale. The California company—founded in Pasadena in 1921 by Charles See and his mother Mary See—had always been run by the See family, but the latest owner, Harry See, was interested in selling the business so he could focus on his Napa Valley vineyard. Robert Flaherty, an investment advisor to Blue Chip stamps, introduced the deal to Blue Chip president Bill Ramsey, who in turn made the call to Buffett.

Buffett was immediately interested—and not only because his wife, Susie, was crazy about the candy. See’s was well-known throughout the state and had a long-standing reputation for quality; when many other candy stores diluted their recipes during the sugar-rationing period of World War II, See’s maintained its recipe and simply sold its candy until it sold out. With its potential for continued strong operations, See’s was notably different from some of the businesses that Buffett had invested in previously. This was not a cigar-butt type of investment, but rather a high-quality business that held the promise of long-term success. And although Buffett had invested in high-quality growth businesses before, notably American Express, the See’s Candies acquisition was reflective of Buffett’s inclination toward such businesses and also performing them as private transactions.

Because See’s Candies was a private company, its financial information would not have been readily accessible to potential private investors. Had they been able to access it, here are the numbers they would have seen: In 1972, the business had revenues of $31.3 million and profits after-tax of $2.1 million (which, based on the normal 48 percent corporate tax rate at the time, would have meant a pretax profit of approximately $4 million). The business had net tangible assets of $8 million. Operationally, the company had 167 stores open at the end of that year and sold 17 million pounds of candy during the year.1

These numbers gave a return on tangible capital (ROTCE)2 of 26 percent. For a business that actually produces a good and does not have an inherently asset-light business model, this ROTCE indicates a very high-quality business able to compound returns at a rate significantly higher than its cost of capital. The question for potential investors at the time would then have been: Is this impressive after-tax return of greater than 25 percent sustainable? In other words, is this a business that can consistently generate better returns than a comparable business with the same assets? Anecdotally, from Berkshire’s letter to shareholders, See’s Candies had a very strong brand especially in the western United States, where it had a dominant market share. It also enjoyed a network of owned stores with dedicated personnel rather than franchisees.3 It operated in an industry with little technological risk and it appeared to have a history of consistent financial performance. All in all, to a potential investor, the company would likely have seemed able to maintain its competitive edge and continue generating a 25 percent (or greater) rate of return on tangible capital.

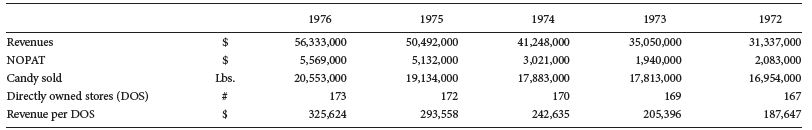

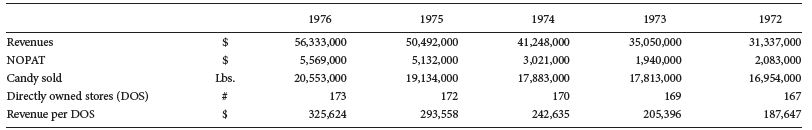

The second trait I would have looked for as a potential investor would have been the company’s ability to grow. Usually, value investors do not want to pay for this growth, but in this case an essential part of the valuation was the company’s compounding ability—hence, an understanding of growth was necessary. This is so because even if a business has a very high ROTCE, if it is not growing, it will not benefit from having to invest less than peers in growth. To assess growth for a product-driven company, I would normally have looked at its historical track record of growing volume or prices. Since See’s operates with directly owned stores (DOS) as its major distribution channel, I would also want to look at like-for-like data per store and the growth in store numbers. While pre-1972 numbers are not available, one can assume, given the consistency of the business, that the post-1972 years serve as a good substitute for what these pre-1972 numbers probably looked like. Those results are summarized in table 7.1.

Table 7.1.

Operating statistics, See’s Candies (1972–1976)

Source: Table 7.1 is reconstructed from data presented on page 6 of Warren Buffett’s letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders dated February 25, 1985.

As table 7.1 shows, in every metric from revenues to operating profits to per store sales (except one off-year) See’s consistently shows growth. In the years between 1972 and 1976, net operating profit after taxes (NOPAT) averaged 16 percent per annum.

Thus, it seems clear that See’s was a company with both high ROTCE and the potential for continued growth. After considering how a potential contemporary investor may have viewed the business fundamentally, one must next consider the valuation of See’s Candies and the price that Buffett paid for it.

Buffett paid $25 million for the entire company;4 knowing the aforementioned earnings figures, one can calculate a P/E multiple of 11.9× and an EV/EBIT multiple of 6.3×. Unlike some of his previous purchases, such as Berkshire Hathaway, this was not cheap in the traditional sense of an extremely low multiple (5× or below). Much more like the American Express case, Buffett paid a fair value for the business. Unlike a business purchased at a P/E ratio below 5×, See’s Candies, at 11.9 times earnings, would have a margin of safety only if the business had a significantly better internal rate of compounding than its competitors. In other words, for a business without growth, a ten to twelve times earnings multiple might be a fair value, but would not provide a margin of safety. And for a business that does have growth but is unable to grow without incurring a cost in additional capital much less than the value of the growth, the value of the growth would be limited. To have a margin of safety, the business must have both growth and a high ROTCE. Thus it seems that Buffett here assumed and paid for at least some growth.

To understand how growth is “priced into” Buffett’s purchasing price, let me give an example. To decide the price at which an investor is willing to purchase a stock, a value investor might calculate the value of the business based on its current earnings and then require a margin of safety of 30 percent. But if this value investor, instead of requiring a margin of safety based on current earnings, is willing to pay full price for current earnings, one can ask another question: how much growth is required to still satisfy a margin of safety of 30 percent? In other words, what growth in earnings is required to make the intrinsic value of a business worth 43 percent5 more than a business with the same current earnings, but with zero growth? Mathematically, the case is fairly straightforward. One can use See’s Candies’s $2.1 million earnings in 1972 as a basis. If one does not pay for growth at all and thinks a fair PER multiple to pay for such a business is 10 times and one requires a 30 percent margin of safety, one would be willing to pay $14.7 million for the business. In this example, the fair value of the business would be $21 million and $14.7 million would reflect a discount of 30 percent to that fair value. Now assume that an investor were willing to pay the full $21 million fair value of the business; what percentage growth per year is required to still provide the 30 percent margin of safety? To achieve this, the growing business needs to have an intrinsic value of 143 percent of $21 million, which is $30 million. Using the simple perpetuity formula6—present value = C / (r − g)—one can calculate the required growth in earnings to achieve a $30 million fair value.7 The specific math is: PV = fair value = 30.0 = C/(r − g) = (2.1)/(0.1 – g) → (0.1 – g) = 2.1/30.0 → 0.1 = 0.07 + g → g = 0.03. It might come as a shock, but the required growth mathematically indeed is only three percent per annum in earnings to get to a fair value of See’s Candies at $30 million.

In the real world, things are slightly more complicated—but not much more. First, to achieve this 30 percent margin of safety requires three percent earnings growth into perpetuity; in reality, few businesses can be assumed to grow ad infinitum. However, because of the 10 percent discount rate, the value of growth in dollars is highest for the first few years, so that a business that grows for ten years would certainly capture the vast majority of the value of growth, even if the growth does not continue forever. Second, the aforementioned would be for a business that just grew three percent per annum without needing any costs to achieve this growth; this is also not true for a business like See’s Candies. For instance, See’s Candies has a ROTCE of about 25 percent, so if the business grows three percent, it will require roughly one-quarter of that amount to finance the growth (if one assumes the capital intensity for the marginal new business is the same as for the overall business). Because of the requirement of growth capital, for a business like See’s Candies, roughly a four percent growth rate rather than a three percent growth rate is required to achieve a 30 percent margin of safety.

Overall, even with these few complexities, two insights are critical. First, if an investor can have a fair amount of certainty about future growth in earnings, even if it is not a high rate but only four or five percent per year, the value of this could be very significant, in fact, as significant as taking a discount of 30 percent when buying a business that is not growing its earnings. Second, given that Buffett paid 11.9× PER for See’s Candies, one can infer that he likely saw and paid for a growth of approximately five percent per year in this business. He must have assumed that this growth would last quite a few years if he ordinarily would only have paid 7× PER (10× PER with 30 percent margin of safety) for a similar business not considering any growth.

Going back to the overall analysis of the business quality of See’s Candies, it seems clear that it fulfilled the criteria of high ROTCE and growth. Buffett seemed to both understand this and be flexible enough to pay an otherwise full price when not considering growth when he had the chance in early 1972. In fact, in his March 1984 annual letter to shareholders, Buffett goes on to tie together his apparent view regarding See’s Candies’s future prospects to the intrinsic operations: See’s Candies is worth more than its book value suggests. It is a brand, it is a product which is able to sell above its cost of production, and it has pricing power into the future.

This investment opportunity was a private transaction, so it would not have been readily accessible for a private investor. Nevertheless, it seems to be a good example of Buffett’s focus during this period on businesses that had the ability to grow consistently with relatively limited additional capital.

In the end, See’s Candies would become one of Buffett’s very best investments. By 2010, See’s Candies earned a pretax income of $82 million on sales of $383 million. The assets on the books at year-end 2010 were $40 million, meaning that only $32 million additional capital had to be put into this business since 1972. At the same P/E ratio of 11.9 times and assuming the now more prevalent corporate tax rate of 30 percent, the value of the firm as of last year would be $683 million. This is a more than twenty-five times increase over the original purchase price even without considering the cash that had been distributed in the interim.