Syed Saad Andaleeb

This chapter provides the students with a basic understanding of Segmentation, Targeting, and Positioning. Students will be able to understand the need for segmentation and how to position a product in selected target markets. In addition to explaining concepts, the chapter refers to a real life segmentation situation through analyzing a case.

Many marketers in the developing countries practice mass marketing. With a vague sense of their customer group(s) or markets, their idea is to offer products mainly in the large population centers, hoping that this approach will result in volume sales. The strategy is often directed at the largest set of customers (e.g., in a major city, at bus or train terminals, on busy streets, places of religious gatherings, large village markets, etc.) by offering a standardized, low-cost item which will supposedly sell because of the product’s functionality and low price. Such a strategy ignores deeper customer characteristics, varying tastes, or their desire to stand out and be distinct. By customizing products closely to fit distinct demographic, psychographic, geographic or some other characteristic, or by focusing on specific customer needs or wants, and considering how they are likely to respond behaviorally to a particular offering, a product’s appeal and desirability can be significantly enhanced.

Such customization represents a focus on segmented markets consisting of a set of customers who share a similar set of needs and wants and behave similarly to marketing appeals and offerings. This set of customers is called a market segment. The act of market segmentation, therefore, represents an effort to identify and categorize groups of customers into clusters that demonstrate some similarity traits. Clustering can also take place at a macro level by clustering communities, regions, or even countries according to some common characteristics (e.g., language, customs, religion, etc.). Segmentation is defined as the process of identifying specific groups of potential customers with homogeneous attributes who are likely to exhibit similar responses to a company’s offering or marketing mix.

As more marketers begin to realize that there is a tradeoff between a standardized price-value proposition and the exclusiveness-distinctiveness ethos that may be desired by customers, a more effective strategy option begins to open up: micromarketing. Micromarketing enables a marketer to craft an offering by fine-tuning its marketing program on a well-defined set of attributes as its competitive offering. The key is to determine the level at which the grouping is done (for a news organization: general news, sports news, or simply cricket news) where the offering is distinct and that distinctiveness can be protected to dominate a particular market segment (i.e., general audience, sports audience, or cricket audience).

The challenges confronting micro marketers are threefold:

• How to identify similar groups of potential customers (segmentation)?

This involves the process of defining segments that have significant potential to respond to marketing efforts.

This involves the process of defining segments that have significant potential to respond to marketing efforts.

• How to choose the segment(s) to target (targeting)?

Marketers must decide on the segments that can be reached most effectively, efficiently, distinctly, and profitably.

Marketers must decide on the segments that can be reached most effectively, efficiently, distinctly, and profitably.

• How to position the product/brand in the mind of the customer (positioning)?

Positioning is required to differentiate the product or brand in the minds of the target market, portraying it as a distinct offering on selected attributes.

Positioning is required to differentiate the product or brand in the minds of the target market, portraying it as a distinct offering on selected attributes.

There is no single way of identifying market segments. The marketer must constantly evaluate the product-market relationship; that is, for which group of customers is the offering to be crafted. Such grouping may be on the basis of geography, demographics, psychographics, behaviors, and benefits. While a conceptual and intuitive understanding of customers in various segments is important, effective segmentation is generally supported by data-driven initiatives. Thus, data gathering and analysis can play a vital role in market segmentation exercises.

Geographic segmentation visualizes the market at different levels of geographic aggregation. This could be regions (South Asia), nations (Big Emerging Markets or BEMS), states (red states and blue states in the United States, depicting political inclinations), cities (by large, medium or small populations), or neighborhoods (as clustered by zip codes or postal codes). Recent work by CLARITAS involves a geo-demographic clustering approach by zip codes in the United States that classifies over half a million residential neighborhoods into 66 distinct lifestyle segments (from blue blood estates to gray power to family thrifts).

In demographic segmentation, the market is divided into groups on the basis of demographic characteristics such as age, income, and gender. For example, teenagers are a group of young consumers who are known for their rebellious attitudes toward cultures and norms. This fact, combined with shared universal wants, needs, desires, and fantasies (for name brands, novelty, entertainment, trendy, and image-oriented products), make it possible to reach the global teen segment with a unified marketing program. Combining this with their multi-billion dollar purchasing power, this segment represents a tremendously attractive segment given its size (about 1.3 billion globally). In the United States, research indicates the existence of 78 million consumers termed as the Generation Y cohort with a purchasing power of $187 billion and growing. This combination of age and purchasing power represents an example of combining demographic categories to create new categories with enormous market potential.

Income is another powerful basis for segmentation. The Gini Coefficient can reveal income disparities within nations that clearly distinguish the rich from the poor. Recent studies have discovered that the poor are not to be ignored as they represent sizeable and profitable market segments, even at earnings of less than $2 per day. Prahalad termed this group as the BOP (Bottom of the Pyramid)1 market; if marketers can craft innovative offerings (sachets, attractive credit terms, products targeted for the family, local distribution, etc.), the sheer volume of sales in this segment can overcome the thin margins to make the segment very lucrative.

Population distribution may also reveal patterns with attractive marketing opportunities. For example, South Asian countries are known for their burgeoning populations, with India at 1.3 billion, Bangladesh at 160 million and Pakistan at 188 million. A closer look at this population reveals the shifting rural-urban densities and how rapid urbanization is creating both threats and opportunities in the major cities. The sheer numbers of consumers moving to the cities suggest how feeding, housing, providing sanitation and heath care, transporting, and entertaining them are areas that have great marketing potential.

Education is a major differentiator of markets, especially in the context of South Asia. The vast educational divide in the region suggests how innovations in education and its delivery can provide distinct opportunities from a social marketing perspective. It is also well-known that education creates its own distinct groups of consumers (books, computers, TV programs, cerebral games, technology solution, etc.). With more people clamoring for education in the developing economies, people belonging to distinct educational categories will represent significant opportunities for marketers.

Religion is a particularly important socio-demographic factor in the context of South Asia. Religious practices are performed with deep devotion; any insensitivity to religious norms and practices can spell disaster for the marketer. The popularity of Halal soap, a brilliant idea conceived by the Aromatic Group in Bangladesh, had such appeal that it literally displaced Unilever’s Lux soap, the number one brand in Bangladesh, during 1997–2001. After the 9/11 incident in the United States and its aftermath, Mecca Cola was launched in the Middle East to appeal to the Muslim population that felt the brunt of US aggression. The desecration of Islamic religious symbols by Nike when launching the “Flame” has also seen the rise of popular protests that shook the organization and made it withdraw the symbol from the product. Famous for its beef burgers, McDonald’s reluctance to introduce the item in India was a smart move. Replacing beef with veggies or fish was even smarter, thus leveraging the brand name. And Pepsi’s sponsorship of programs during the Navaratri festivals in India led to its successes that are mentioned in several business cases.2 When marketing plans touch religious values and practices, local sensitivities and customs must be clearly understood.

Gender-based approaches to marketing have also seen many successes. Believing that its global business targeting women is poised for big growth, Nike generated $1.4 billion in global sales of women’s shoes and apparel by targeting them in creative ways, which represented 16% of total Nike sales.3 The new Fair & Lovely MAX Fairness Face Wash for Men featuring Saif Ali Khan (Indian film star) and how the product deep cleans the effects of pollution and dirt from one’s face to provide long-lasting fairness is another example of targeting men with skin care cosmetics that traditionally targeted women.

Psychographic segmentation creatively combines demographics and consumer psychology to profile groups of customers who are likely to respond similarly to one or other marketing effort by a company. This technique is credited to SRI (Stanford Research Institute) Consulting Business Intelligence’s VALS (values and lifestyles) framework which is based on grouping people according to their attitudes, values, traits, and lifestyles. The approach has used over 80,000 surveys per year to create the VALS, and subsequently VALS 2, segmentation system. Another psychographic study showed that Porsche buyers could be divided into several distinct categories in which Top Guns, a narcissistic bunch, buy Porsches because they expect to be noticed. Yuppies (young professionals), Zoomers (55+ group), and DINKS (dual income no kids) also represented psychographic groups in the developed world with similar traits to be targeted with similar marketing programs.

Market segmentation that focuses on behaviors of customers is directed at finding out whether people purchase a product or not, how much they purchase, and how often they use the product. Buying decision roles are also considered in this type of segmentation where buyers can play one or multiple roles as initiators, influencers, deciders, buyers, and users.4

User status, for example, is an important behavioral characteristic that interests many marketers. In this framework, a buyer can be a non-user, ex-user, potential user, first-time user, and regular user. This information is key to introducing loyalty programs in an effort to build a long-term customer base. Studies have shown that on the basis of Pareto’s Law, 80% of a company’s revenues are accounted for by 20% of its customers. It is vital for companies to find out who are the 20% of buyers who account for the majority of purchases.

Benefit segmentation is perhaps at the heart of the marketing concept because it attempts to find groups of buyers on the basis of benefits they seek from a particular product. Based on marketers’ understanding of the problem that a product solves or the benefits it offers, connecting with the customer becomes easier. Marketers of health and beauty aids use benefit segmentation extensively. The story of Crest toothpaste is legendary in highlighting benefit segmentation. In its early days the company was able to identify a key benefit buyers were seeking that other companies ignored: cavity protection. Once the idea was implemented, the place of Crest toothpaste was firmly ensconced in the milieu of competitive offerings. However, as consumers have become more concerned about whitening, sensitive teeth, gum disease, and other oral care issues, marketers have been developing new toothpaste brands suited to the different benefits sought by the customer. Many Europeans are concerned about their pets, especially their health and longevity. In response, Procter & Gamble is marketing its “Iams” brand premium pet food as a way to improve pets’ health.

The value equation can play an important role in benefit segmentation that capitalizes on the concept of benefit divided by price. As shown below, the value proposition can be enhanced by increasing benefits (via improving process or outcomes) or lowering price (in monetary, physical, psychological, or emotional terms) to the customer.

Value = Benefits/Price

Market segmentation strives to identify groups of customers with similar needs, and analysis of the buying behavior of these groups. This leads to the crafting of marketing mixes that match the characteristics of the segment. Ultimately, segmentation helps marketers satisfy customers’ wants and needs while at the same time meeting the organization’s objectives.

For successful segmentation, the following criteria are vital:

Substantial: Segments must be large enough to warrant designing a marketing mix that will turn a profit.

Identifiable and measurable: Segments must be identifiable and their size measurable on the basis of demographic and other measurable criteria such as attitudes or benefits sought.

Accessible: Targeted segments must be easy to reach with marketing mix elements such as promotion and distribution.

Responsive: Different segments ought to respond to different marketing mix offerings; otherwise, they need not be treated as distinct.

Consistent: The segment(s) selected must be consistent with the company’s overall objectives, as well as its strength to deliver (financial, managerial, employee skills, and facilities).

Once a firm has developed its market segment opportunities, it must decide which segment or segments to prioritize and nurture, and which ones to ignore or assign low priority. Three basic criteria must be fulfilled to hone in on selected target(s). These include as follows:

• Current size of the segment and anticipated growth potential

• Potential competition in the segment

• Compatibility with the company’s overall objectives and the feasibility of successfully reaching the target audience.

Experts believe it may be better to look at a small but growing segment instead of eyeing large segments where competitors may have already established themselves; thereby providing low to no growth opportunity. When digital cameras were being introduced, the potential market was the driving factor instead of the existing large market of film-based cameras. Thus, market size and anticipated growth are preliminary considerations in selecting specific targets. In addition to running successful marketing programs in selected segments, it is useful, as suggested earlier, if the segments are measurable (through surveys and related statistical means), substantial (potential for profit), accessible (via different channels of communication and distribution), differentiable (having different response functions), actionable (via effective marketing programs), and consistent with the firm’s objectives and resources.

Success in a selected segment also depends on the extent of competition in the segment. Thus, it is important to assess the target market in terms of Porter’s five forces to assess the viability of entering the segment and sustaining a firm’s marketing programs in the segment.5

Competition can be met strategically in a variety of ways. Concentrated marketing or niche marketing is one way of dealing with competition. Here, instead of the competition defining the market and the offering, it remains the firm’s prerogative to define its target market. For example, today we see many 24/7 TV news channels in South Asian countries that emulate CNN’s approach to defining who, how, where, and when to serve its chosen segment with news and carve out a niche. In other words, instead of finding itself with a small share of the large market, these TV channels seek to grab a large share of the small but growing market they can dominate in future. Concentrated marketing seeks to serve the interest of a single segment (fashion) of a broader market (readymade garments), looking for depth rather than breadth.

The alternative is to choose a multi-segment targeting strategy by choosing to go after two or more distinct markets (see Chapter 3). Honda’s decision to introduce a range of automobiles (the Odyssey, Accord, CRV, Civic, Fit, etc.) to serve the needs of different groups of customers is a case in point that enables it to attain wider market coverage and battle competition on their own turf. Such a strategy must of course be compatible with the firm’s overall ethos and objectives while being feasible from a financial and human resource perspective.

Once the market is segmented and suitable target customers are identified, it is important to locate a company’s brand in consumers’ minds relative to competitors, carefully selecting the distinct attributes and benefits that the brand promises to offer.

Pepsi’s positioning strategy is shown in the figure below:a

It is important for firms to select a positioning strategy carefully as customers will associate the brand with the way the company wants to connect with its customers. This concept is also tied to a concept termed the unique selling proposition or USP. In addition to the positioning concepts shown here for Pepsi, other products or brands may select unique attributes for positioning such as performance, durability, nimbleness, convenience, caring, or some other suitable USP that is based on identifying the competitive advantages accrued by a brand.

In addition to highlighting the advantages of the product, a company can also choose to position itself on service criteria like reliability, responsiveness, empathy, etc. or make the “people” in the company prominent who make the company or brand what it is.

For effective positioning, the company must select the key features to promote. The advantages of these features must be easy to communicate, distinctive, superior to the competitive offerings, and affordable. Unless the positioning is pre-emptive, the brand or company may be seen as a “me too” entity with no distinctive positioning.6 Of course, the “me too” positioning could itself be a strategic choice depending on considerations of market entry timing and the competitive milieu.

The real task of positioning is to highlight the distinctive advantages using the marketing mix. In other words the right mix of product features, price, promotion, and place must be harmonized and constantly adjusted, on the foundation of ongoing research, to determine whether the desired position has been attained.

CASE 1: SEGMENTATION, TARGETING, AND POSITIONING

Square Toiletries Ltd & Senora: Overcoming Cultural Taboos

Syed Saad Andaleeb

The Square Group started out in present-day Bangladesh as a small pharmaceutical partnership venture in 1958. Within four years the business began to turn a profit and grew steadily. By 1985, the venture had attained a strong leadership position in the pharmaceutical industry despite severe challenges from several multinational companies. Today the flagship company — Square Pharmaceuticals Ltd. — is on its way to becoming a contender for a global spot as a manufacturer of pharmaceutical products.

The Square Group did not stop at being the leader in the pharmaceutical sector only. Over the last 50 years, the company slowly but steadily diversified itself, making forays into other strategic sectors, including health care, textiles and readymade garments, toiletries, consumer goods, information and communication technologies, and even the media.

Within the Square Group, Square Toiletries Ltd. (STL) is one of Bangladesh’s leading manufacturers of cosmetics and toiletries. With 18 strong and recognizable brands (Exhibit 1) in a wide range of product categories, STL’s motto is to “uniquely touch the lives of millions of people in Bangladesh and beyond.” These brands have continued to play a significant role over the years in the areas of health care, skin care, hair care, oral care, baby care, fabric care, and men’s grooming.

Exhibit 1: Toiletry Brands at STL.

Square Toiletries Ltd. (STL) symbolizes innovation. STL is the pioneer for bringing in new products and packaging concepts in Bangladesh. Currently, STL is carrying out its production in its two fully automated plants at Rupshi and Pabna in Bangladesh.

With state-of-the-art production facilities, most advanced equipment, and high quality raw materials, STL ensures the absolute best for its customers. Depending on the nature of the products, formulation, and packaging, STL uses product-specific machinery. A group of well-trained people always ensures the smooth operations of all machinery. Imported from various foreign suppliers, the best quality raw materials are used for all STL products. Each phase of the production process undergoes rigorous testing to meet international standards, following the GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) of production.

Square Toiletries Ltd. has a strong R&D department which is committed to developing new products and improving existing products. The international standard products of Square Toiletries Ltd. meet the needs of Bangladeshi people as well as the people abroad. The objectives of R&D are as follows:

– A deep understanding of consumers, their habits, and product needs.

– Capabilities to acquire, develop, and apply technology across STL’s broad array of product categories.

– The ability to make “connections” between consumers’ wants and what technology can deliver.

Source: http://www.squaretoiletries.com/manufacturing_unit.php

Dominated by imports in a large and growing domestic market, personal care products in the past were mostly aimed at the middle- and high-end segments, appealing to them with quality products that were priced to create an exclusive and upscale appeal.

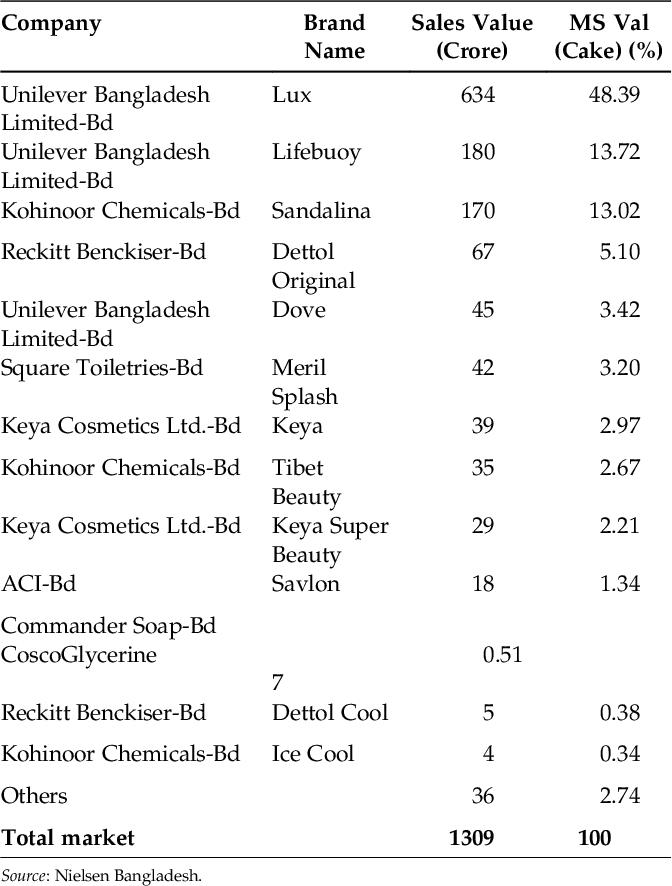

Recently, however, aspiring customers, generally ignored by the importers, have begun to demand a share of personal care products. As a result, locally produced toiletries have begun to grow rapidly in Bangladesh, targeting customers in the middle-to-low price market segments with satisfactory products that are reasonably priced. These local manufacturers have in fact begun to establish their own brands (see Table 1). Data suggest that all of the major toiletries firms have experienced steady growth. Many of the local manufacturers have also started exporting cosmetics and toiletries products from Bangladesh to the region.

Table 1: Market Share of Major Soap Brands of Bangladesh (MAT Nov’ 13).

Since the mid-1980s, industries in Bangladesh have begun to experience a new phenomenon: the twin forces of open markets and gradual deregulation. In 1986, significant changes were introduced in the import procedures, whereas, prior to 1986, there was a lengthy Positive List of importable toiletries. In 1986, it was replaced by two lists, namely the Negative List (for banned items) and the Restricted List (for items importable on fulfillment of certain prescribed conditions). Items outside the lists were allowed to be freely imported if they were backed by letters of credit (LCs). These changes represented a significant shift toward import liberalization and opening of the market to foreign products.

In 1991, in order to encourage and bolster investment, the provision of obtaining prior clearance to set up new industries was abolished. Consequently, many domestic industries, accustomed to tariff protection, began to find themselves in a new environment of competition that made them vulnerable to an increasing presence of foreign firms. The reduction or removal of tariff and other non-tariff barriers, along with the influx of smuggled goods from neighboring countries resulted in additional challenges for many domestic producers. Local competition also increased substantially over the years with new entrants in the market. It is this regime of trade and investment liberalization that defined the growing and competitive nature of the economy in which STL had to make its mark.

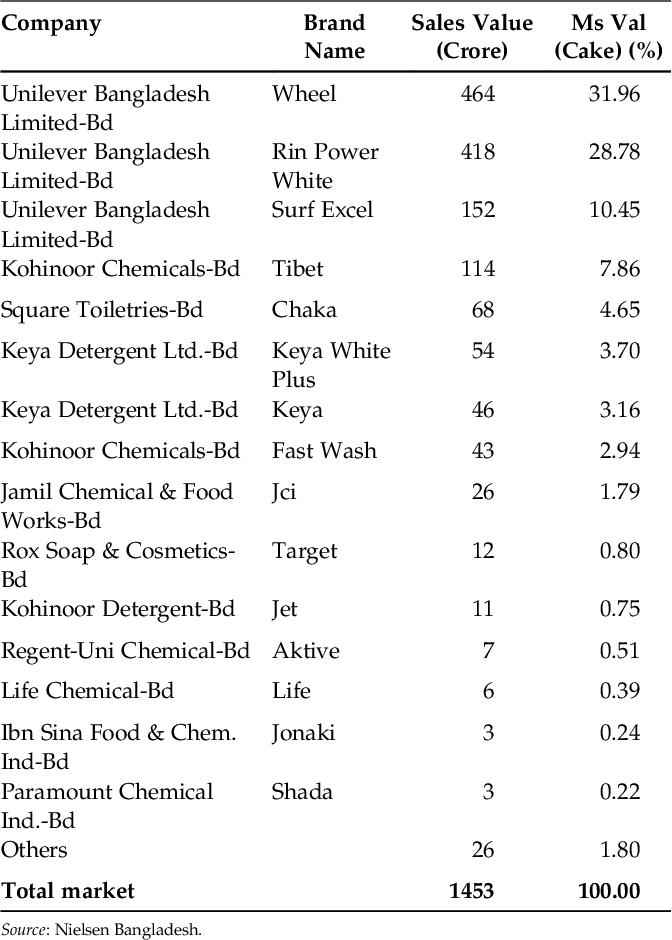

While the toiletries industry consists of a large number of firms, Tables 1 and 2 show that 13 firms contribute to the market for toilet soap, laundry soap, and detergents. Unilever Bangladesh Ltd. has been the market leader with more than 66% of the annual market share of toilet soap and 71.2% of the detergent market. Table 3 shows the estimated combined market share of the total toiletries market of major five toiletries firms. Approximately 50% of the toiletries sector is controlled by one multinational company that commands substantial market power.

Table 2: Yearly Market Share of Detergents (Mat Nov’ 13).

Table 3: Estimated Market Share of Major Five Toiletries Firms (May–July 2013).

Company |

% Against Toiletries Market |

% Against Total FMCG |

Toiletries/FMCG Industry |

BDT 8700 Cr. |

BDT 17,500 Cr. |

Unilever Bangladesh Ltd |

40 |

20 |

Square Toiletries |

9 |

5 |

Marico |

6 |

3 |

P&G |

2 |

1 |

Johnson |

1 |

0 |

Source: Nielsen Bangladesh and Square Toiletries Limited.

Manufactured by Square Health & Hygiene products, Senora was first launched in Bangladesh in 1989. Over the years, Senora became the market leader in the sanitary napkin category, commanding roughly 75% of the market. Competing brands like Whisper (P&G), Mona Lisa (Boshundhara) and Nirapod (BRAC) also entered the market at different times but still remain fledglings. Committed to ensuring health and hygiene for women, Senora aims at freeing women who have attained puberty from worrying so that they can pursue a variety of activities in their daily lives.

Senora sanitary napkins are manufactured with high quality imported pulp which absorbs fluid and provides a constant feeling of dryness. The sterilized product has air-laid paper and Perforated Poly Film (PPF) that provides a sense of liberty to women to move freely without worrying about leakage. Senora is available in a range of products, providing relief for heavier to lighter days. Another variant manufactured by STL has a belt-like design that is self-supporting.

Gaining customer favor in the sanitary napkin market has been a long drawn-out process, reflecting sustained resistance to the product, despite its positive health and hygiene features. While good research on customer resistance toward the product is lacking in Bangladesh, Um-e-Kulsoom Shariff cites two sources of resistance that appear to be very strong in a similar market in neighboring India. For example, in 2010, the research agency Nielsen found in a nationwide survey that 70% of women in India cannot afford sanitary napkins. Until recently, sanitary napkins had a luxury tax of 14% that was reduced to 1% after pressure from advocacy groups and NGOs. Yet only 12% of the 355 million women in the country experiencing periods use them. In rural India a mere 2% of women use sanitary napkins, even though roughly 75% of the target population lives there.

Shariff goes on to point out that many Indian women use paper, sand, ash, or even leaves during their periods, despite doctors’ warning that these unhygienic habits can lead to tremendous discomfort in addition to possible serious infections. Usually women who have never used a sanitary napkin rely on an old piece of cloth. The usual refrain about this practice is “Napkins are expensive. A cloth can be used repeatedly after washing.” Marketing executives at Square Toiletries indicated encountering similar practices in Bangladesh, leading to a variety of health problems.

Building the market for sanitary napkins has been challenging at best. According to Malik Muhammad Sayeed, Head of Marketing at Square Toiletries, “In developing countries like Bangladesh, talking about ‘the cycle’ is taboo where girls are unwilling to discuss the matter even with their mothers, teachers, or friends.” When they face a serious problem, asking for a sanitary napkin is a near insurmountable cultural hurdle. Relating the predicament of women, Malik observed that even the better-off and educated women in urban settings continue to display a sense of embarrassment and hesitation of going to the retail stores in search of sanitary products, especially to avoid any interaction with the male sales staff who generally dominate the retail sales environment. Some of these women even go to the extent of purchasing sanitary products far from their own neighborhood to keep the matter as private as possible. Moreover, instead of going to the stores themselves, they usually send the female help in their homes to purchase the product. For a natural physical condition requiring a safe and hygienic solution, the cultural barrier, seemingly, has not been easy to overcome.

After attempting many approaches to marketing the product, even to the extent of experimenting with home delivery using salesgirls, STL identified a target market for Senora of apparently high value: 1.6 million girls of school-going age in the 11–14 age-groups to be developed as long-term customers. The idea was that once they got used to the product, they would continue using them over a substantial part of their lives. The strategy took on a more significant dimension after the Education Minister of Bangladesh endorsed the idea of including material in the school textbooks, highlighting the desirability of using sanitary napkins.

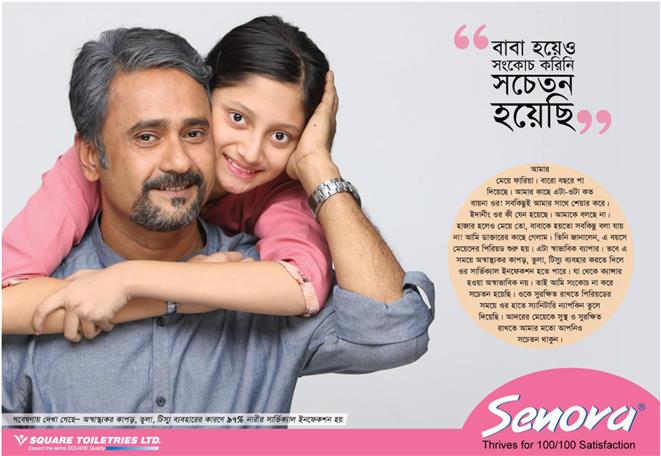

To fulfill this strategy and build the needed customer base, a promotional theme — “be aware, not embarrassed” — was developed. This was conveyed through video production and direct counseling and was reinforced with a product sampling strategy, allowing the target group to take home free samples (see Appendices 1–3). In Appendix 1, the young girl’s father is thinking, “Although I am a father, I decided to become more aware.” In Appendix 2, the girl’s mother is thinking, “To protect my daughter, I became more aware.” In Appendix 3, the schoolteacher reflects, “As a responsible teacher, I became more aware.” Parents and school teachers as potential facilitators of sanitary napkin usage are apparent in the messages.

STL also launched a program to train school teachers, gynecologists, mothers, and even retailers to play a vital and supporting role in the campaign. For urbanites, a communication program is being crafted with the assistance of USAID to establish a toll-free call center so that any questions relating to health and hygiene, especially pertaining to the use of feminine products, could be readily addressed.

An online discussion forum is also contemplated to raise awareness among the target group and address cultural taboos and barriers that served to heighten customer resistance to an idea whose time had arrived in the country. Similar strategies have been adopted overseas; for example, P&G pursued the idea of attracting consumers to interactive sites of interest with the hope of developing deeper relationships with consumers. P&G launched a website for teenage girls with information on puberty and managing relationships, while promoting products such as Clearasil and Tampax. The website, www.beinggirl.com, was designed with the help of an advisory board of teenage girls: the target customer!

Understanding the importance of personal hygiene, Senora has been working on changing the situation for the past 20 years. Educating girls of high school age, introducing silent purchase coupons, and making mothers aware of their daughter’s discomfort are ideas being pursued to change many age-old mores and taboos that have barred women from adopting healthy habits and practices. Ever so slowly, according to Jesmin Zaman — Marketing Manager of STL — girls are beginning to ask for sanitary napkins in retail outlets and girls’ schools. Women in office settings are also keeping the product handy for emergencies.

A study by Nielsen in Bangladesh indicated a market penetration rate of a mere 2.5%. Senora brand managers at STL, however, estimated that the Nielsen data did not represent the pharmacy distribution chain properly. In their estimate, the brand penetration of Sanitary napkin is only around 6%. With 94% of the market yet to be reached, and in anticipation that the long introductory phase of the product life cycle (PLC) has finally begun to show an upturn into the growth phase, STL recently added two new machines with a production capacity of 1000 sanitary napkins per minute. The marketing team at STL is confident that the inflection point between the introductory and growth stage in the PLC is imminent and that they are prepared to meet the expected surge in demand.

The growth of the Square Group and its success both within the country and abroad has been infectious within the conglomerate. The Indian market is particularly lucrative for many personal care products from Bangladesh. This contention is predicated on a number of factors including India’s fast-paced economic growth, the rise of the middle class, and the opening of the market, albeit slowly, to global companies (including Wal Mart). The broad idea of “personal care” has grown rather dramatically among India’s growing numbers of working women. Before other global competitors gain market share and given Bangladesh’s proximity to the Indian market and many cost advantages, this is an opportune time to consider this market seriously. Several opportunities appear to be ripe for examination and eventual exploitation.

One potential target is the young urbanites — more specifically, working women in their 20s — who work and/or reside in urban areas. Combining their demographic and psychographic profiles, this is a lucrative segment. According to Vaja,7 the young urban population is projected to increase, especially working women, suggesting future growth potential of this segment. In fact, the age group between 15 and 24 represents 18.2% of the total Indian population, which translates to 103,660,359 females,8 a significantly large market size; for instance, this figure alone represents nearly a third of the total US population.

Women in their 20s were also found to be concerned with the visual effects of aging. Their desire for beauty products that slow or minimize the appearance of age suggested the need to introduce wrinkle creams and treatments, tone eveners, skin softening creams, and more. STL could easily leverage its strengths in these product categories.

A second potential target segment in this broadened market could be India’s population characterized as the “Bottom of the Pyramid” (BOP) — a vast number living on $2 per day or less. While the segment is large and number in the hundreds of millions, their discretionary income is small. Would they spend money on goods that are not labeled as necessities, such as food, water, and shelter? Research suggests that people in the BOP purchase non-necessity goods, like televisions and personal care items. In fact, 54% of women reported in a survey that they would spend 50% or more of their income on beauty products (Understand Consumer Buying Behavior for Beauty Products).7 Even with a small income, a majority of the women purchase beauty products because they want to look attractive and to feel confident.7 As a basic, universal, human need, no matter how much money one makes or where one is located in the world, people want to be liked and accepted by others, and will do what they feel is necessary to make that happen. The strategy of reaching this segment would be to enhance their attractiveness and to build their confidence; being perceived as attractive would make them feel more accepted by others. Hindustan Lever (HL) had already penetrated this segment by introducing $0.70 bottles of lotion and $0.90 bottles of perfume.9 The competition in this segment would be intense. Nevertheless, the way to take on HL would be to offer single-use shampoos, conditioners, body lotions, and soaps and sell the items at competitive prices to challenge HL’s dominance.

A third potential segment would be the Muslim population whose psychographic characteristics — that is, their values, lifestyles, attitudes, and interests — are unique. According to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) World Factbook10 only 13.4% of India’s population is Muslim projected to increase to 15.9% by 2030. The reason Muslims are not widely targeted in the cosmetic industry is because they value and require Halal ingredients — that is, products which are not only natural and organic, but also free of animal derivatives, as well as alcohol. Providing Halal-certified cosmetic products could allow STL to capture this largely untapped market. One specific product that could be introduced could be a Halal-certified whitening cream, as many Indian women also prefer lighter makeup and “brightening” and “whitening” products aimed at giving them a brighter, lighter, and perceived “better” complexion.11

A growing interest in cosmetics is also trending amongst Indian men, and they are willing to pay a premium price. According to Sharma, the male cosmetic business is an Rs. 3800-crore market; this market segment is expected to hit Rs. 5270 crore in three years.12 While overseas markets represent numerous challenges, rich dividends await the Square Toiletries Group in its quest to become a global player.

1. What are the different segments for STL’s sanitary products?

2. What are the sources of “resistance” to adopt STL’s sanitary napkins? Can “resistance” be a segmentation variable? Discuss.

3. Assess the different strategies launched by STL to gain entry into the large potential market in Bangladesh.

4. Suggest an alternative strategy that STL may have missed on marketing sanitary napkins.

5. Should STL consider entering the Indian market nextdoor with “personal care” products?

There is no single way of segmenting markets. In the STL case, the alternatives could be demographic (age, income, education, faith, or some combination), behavioral (usage rates), benefits sought (low price vs. hygiene), etc. The idea to keep in mind is that the segments selected must meet four critical criteria: identifiable and measurable, substantial, accessible, and responsive (or actionable).

1. Inability to afford the sanitary products

It is no secret that many families struggle with their income level in these countries. As a result, sanitary products may be viewed as a luxury compared to cheaper alternatives (listed below).

2. Cheap/free (but also unsafe) alternatives already being used

Potentially harmful practices such as the use of old rags, paper, sand, ash, or leaves can leave women with health problems but is a significant threat to the adoption of sanitary products seeing as how they are easily accessible and often free. While doctors may recommend otherwise, many Indian women feel that they cannot afford the safe route and would rather use the free alternatives.

3. Cultural resistance and discomfort

Many young women are unwilling to discuss their sanitary issues with anyone, even their family or friends. Additionally, they feel uncomfortable buying these products in stores that primarily employ male workers.

STL has looked into a variety of strategies.

(a) Target younger women

While many older women are likely to be set in their ways, younger women are likely to have more open minds to using and purchasing sanitary products.

(b) Introduce the products via the educational systems

This is a longer term approach. Many of us remember hygiene lessons that were taught in school when the mind was open and receptive to what teachers had to say. If education is valued in these cultures and the teachers are creative in conveying that sanitation is important, the children will respond positively and adopt hygienic means in future.

(c) Online discussion forums:

This method is interesting, although it would be missing a large part of their target market due to lack of Internet access or Internet navigational skills to find such a forum.

(d) Silent purchase coupons

This process has a confidential aura while limiting exposure of the women when they have to buy the products.

Students may break away into groups and attempt to come up with additional and culturally consistent ways of connecting with a define target market.

Students are urged to think of what resources (financial, human, technological, relational, etc.) and approaches (segmenting, targeting, and positioning) are likely to make the entry decision successful, in addition to considering market entry modes (licensing and joint ventures, to foreign direct investments, each approach contingent on trade relations between the two countries).

The ad is playing with regional cultural practice to reinforce/establish the value of the brand. In Bangladeshi culture, it is rare that daughters discuss personal issues with their fathers. The ad is trying market the product by tapping into an apparent cultural shift by making the brand one of the agents for change. The texts between the quotation means “despite of being a father, I did not hesitate to be aware.” These texts when viewed with the picture of the father and daughter would hint that the quality and promise of the product is making a father ignore cultural taboos.

The ad is designed to tap into the deep bond between mother and daughter. The picture, when coupled with the quoted text (as a mother, and to protect my daughter, I became more aware), exudes the relief of a mother regarding period due to the quality of the product.

The ad is using the teacher-student bond as a basis for establishing the quality and assurance of the brand. The quoted text is a statement from any responsible teacher and these texts when viewed with picture, the audience will depict a sense of reinforcement for the brand.

Acknowledgments: The case was written with the assistance of Malik Muhammad Sayeed, Head of Marketing and Jesmin Zaman, Marketing Manager at Square Toiletries Ltd. Research on the Indian market was conducted by Angela M. Sweeny while a student at Pennsylvania State University, Erie. The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance received.

CASE 2: SEGMENTATION, TARGETING, AND POSITIONING

Japan’s Most Successful Automobile Brand

Al Ries

Japan is known for automobiles. Some of the most successful global automobile brands were created by Japanese companies. They include Toyota, Honda, and Nissan. In the year 2015, for example, Toyota had sales of $227.6 billion and a net profit margin of 8.0%. Honda had sales of $111.4 billion and a net profit margin of 3.8%. And Nissan had sales of $95.1 billion and a net profit margin of 4.0%. That’s typical. Larger companies not only make larger total profits, but they also tend to have a larger profit margin. It’s the economy of scale. Toyota’s 8.0% net profit margin is double that of its two smaller competitors, Honda and Nissan.

But here’s the surprising fact. One of the smallest Japanese automobile brands is the most profitable (in terms of net profit margins) and also the fastest growing. It’s Subaru. And here’s the marketing story.

Picture: One of the popular brands of Subaru in the auto markets in North America.

Subaru is owned by Fuji Heavy Industries of Japan. Last year, 2015, the company had sales of $24.1 billion. Profits of $2.2 billion, or a net profit margin of 9.1%, higher than even Toyota.

As a small automobile company in Japan, Fuji Heavy Industries has a choice to make. The Japanese market is just not big enough to support an automobile company. To survive, an automobile company had to sell its products in other markets. But what markets should it choose?

Big companies like Toyota, Honda, and Nissan could afford to set up branches in most countries in Asia, but not Subaru. It’s just not efficient for a relatively small company to try to compete in every market.

So, Subaru decided to focus on the American market and today Subaru sells almost 90% of its vehicles in just two markets, Japan and America. (Sales in America are 3.6 times sales in Japan.)

Subaru also sells a small number of vehicles in China, Europe, Australia, Canada, Russia, and other countries, but the brand would probably be even more profitable if it had focused on just Japan and America. But the Subaru brand was not always successful in America. Quite the contrary. In the year 1993, for example, Subaru had sales of $1.4 billion in the American market, but lost $250 million. So a new president, George Muller, was hired.

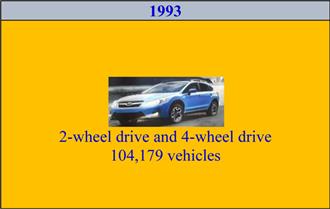

Subaru had pioneered four-wheel-drive vehicles (what the auto industry calls “all-wheel drive”) but not all customers wanted them. Up north, four-wheel drive was very popular, but not in the south, where snow and ice are rare. So Subaru, being customer-focused, sold both four-wheel-drive and two-wheel-drive vehicles. In 1993, 48% were four-wheel drive and 52% were two-wheel drive.

“If you asked a Subaru dealer or an employee or the press what Subaru was all about, it was pretty confusing,” said George Muller when he took over as president of Subaru of America. So he decided to focus on four-wheel-drive vehicles. Advertising theme: “The beauty of all-wheel drive.”

It was a bold decision, but, it didn’t take long to turn the brand around. Three years later, Subaru was essentially a four-wheel-drive brand and sales were up from 104,179 to 120,748 units, a gain of 16%.

In the years that followed, Subaru has consistently outperformed the automobile market. In 2015, Subaru sold 582,675 vehicles in America, an increase of 459% over the year 1993. (The overall automobile market was up only 26% in those 22 years.) Today, America accounts for almost 70% of Subaru’s sales. If the company had not focused on America, it might not be still in business.

In 1993, Subaru was the 23rd largest-selling automobile brand in America. By 2015, Subaru was the 9th largest-selling automobile brand.

In business today, there is enormous pressure to increase sales. But how do you do that? The typical response is to increase the number and types of products you sell. That’s what Subaru initially tried to do.

So not all customers wanted to pay a little extra for four-wheel drive, so Subaru also offered two-wheel-drive vehicles. That made sense in the marketplace, but didn’t make sense in the mind of the prospect.

What’s a Subaru? In order to provide an answer to that question, Subaru had to narrow its focus to a singular attribute. Fortunately, the company had a unique attribute in four-wheel drive which initially it squandered by trying to be both four-wheel and two-wheel drive.

As companies get bigger, they often sacrifice their marketing advantage by trying to be all things to everybody. That seldom works.

Subaru is made in Japan. The data show that Subaru being a Japanese vehicle has consistently outperformed the automobile market in the United States. In 1993, Subaru was the 23rd largest-selling automobile brand in America and by 2015, it was the 9th largest-selling automobile brand. What is the learning point for other Asian manufacturers penetrating in other markets?

The business is global. The Asian manufacturers should understand the need of different segments, availability of resources (such as human, financial, and technological) and macro-environmental factors through market research across the globe. The information will help to identify the target market and position their products and services accordingly. And Japanese are doing that for more than half a century. Most importantly, the manufacturers should think that the present marketing approaches are no longer country-based rather it became global. Coming out of “comfort market” and taking challenges to create own market is the learning point from the Japanese business icons! Bold and immediate actions — the right mantra!

a. http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=pepsi+positioning+strategy&qs=AS&sk=AS1&FORM=QBIR&pq=pepsi%20positioning&sc=3-17&sp=2&qs=AS&sk=AS1#a)