Chapter Three

Minuet (1940–1941)

On one hand the city was swept clean by the police, by official authority, while on the other, the people each day traced the contours of a city that it redesigned according to the season, or some crisis, even sometimes an angry outburst. Thus [Paris], in its bistros, in its neighborhoods, escaped the powers that organized and repressed [it].

—Pierre Sansot1

How Do You Occupy a City?

Article 43 of the regulations enacted at the Hague Convention of 1907 states succinctly: “The authority of the legitimate power having in fact passed into the hands of the occupant, the latter shall take all the measures in his power to restore and ensure, as far as possible, public order and [civil life], while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country.”2 Such benign language assumes that all occupying forces see their primary duty as maintaining a semblance of antebellum everyday life. Yet it suggests that the occupier might well read in the innocuous phrase “as far as possible” a loophole that would permit him to do whatever he wants. Also, there is no reference in this article to the notion of time: How long is an occupation? Can it go on forever? Is it an implied temporary state, or is it open-ended? One of the cruelest impositions on an occupied nation is the idea that time is also an enemy, a heretofore anodyne phenomenon that becomes a patient, insatiable consumer of hope. A military occupation is no longer just the temporary appropriation of sovereignty.*

Initially polite, the Occupation authorities in Paris became more and more exigent. The newly returned population noticed immediately that many of the city’s elite hotels and luxurious private residences had been confiscated by the Germans—for the Wehrmacht, the Luftwaffe, the Kriegsmarine, the Gestapo, the Foreign Office, the propaganda ministry, and so on—and that whole sections of the city were closed off to the casual pedestrian. Next they became aware of yellow signs affixed to the shop windows of all Jewish-owned enterprises.* The Germans wanted the residents to know which businesses were Jewish-controlled in the hope that “proper” French people would not shop there. Later, these yellow notices would be replaced with red ones announcing the presence of an “Aryan manager,” that is, someone selected by the authorities who had paid for the rights to the establishment’s management and profits. Strictly enforced food rationing began within weeks, revealing, though no one knew it then, a German strategy: to use the bounty of French agriculture to feed the armies of the Reich and to reduce the French to a minimal caloric intake. Eventually, Parisians had to accept hunger as a price for staying on the Seine.

Accounts of the months following the first surprise of the Occupation mix self-disgust and political despair to create an almost palpable despondency. It was one thing to see German soldiers in expected places—before major buildings, monuments, crossroads—but quite another to run into them on side streets or in one’s favorite café. They seemed to have come out of nowhere, silently, to infest the city. For every Parisian who had welcomed them with surprise and respect there were now a dozen who felt bereaved, lost, forgotten. How had Paris, the heart and brain of France, been so effortlessly occupied? No counterattacks, no street-to-street fighting, not even a sign of a fruitless but symbolic resistance. How could this have happened in Paris, of all cities? Jean Guéhenno, in his Journal des années noires (Diary of the Dark Years), describes his return to Paris once the Armistice allowed him to leave the French army. He found Paris saddened and bleak, not the place a few had described as relieved, even happy, to see the Germans. He lived near the Bois de Boulogne, on the western side of Paris; almost offhandedly he noticed that something was not quite right, though there were no signs of Germans in the neighborhood. Then he figured it out: birds were no longer singing on those hot September days. Had they, too, fled?

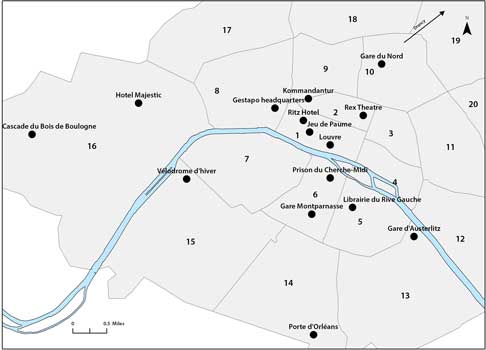

Sites of the Occupation

Though physical resistance to the enemy was almost nonexistent, verbal and graphic expressions of anger or of a stubborn refusal to accept the obvious were soon present—and often humorous. Graffiti, flyers, and small tracts glued to lampposts almost immediately began to appear. Many of these first expressions of discontent were from the hands and imaginations of adolescents, delighted to have a patriotic reason to cause mischief. In his sad biography of the young Communist Guy Môquet, later to be executed as a hostage at the age of seventeen, Pierre-Louis Basse describes the exhilaration of teenage resistance: “[After] the surrender and the arrival of the Germans in Paris… the working-class youth of the 17th and 18th arrondissements wasted no time in playing cat-and-mouse with the French and German authorities.”3

Mimeograph machines became precious and were hidden imaginatively all over the city; their stencils were inserted into the pumps of bicycles coolly ridden past the authorities. Papillons (butterflies)—small, toilet-paper-thin documents—were dropped from rooftops, bridges, and speeding bikes onto Germans and Parisians alike. There is an ingenious contraption on view at the Musée de la Résistance nationale in Champigny-sur-Marne that was designed to project these papillons from balconies and rooftops long after the perpetrator had left the area. The machine is constructed of a mousetrap weighted down by a tin can with a hole in its bottom; the can is filled with water, and as the leaking liquid lightens the can, the gadget pops the container of messages on the other end into the air. To the great amusement of the young résistants, bits of anti-Nazi propaganda would fall like snowflakes onto the heads of a German marching band or foot patrol.

For Some, Paris Was a Bubble

We know from several sources written during the Occupation that there was an often warm relationship between many of France’s most talented citizens and the better-educated German occupiers. The upper echelons of society, if they were not Jewish, enjoyed a comfortable life, even though they could not get every foodstuff they wanted or have their drivers pick them up every morning. What we know less about is how difficult materially the Occupation was for the middle-of-the-road Parisian. There was more illness, to be sure, more malnutrition, but there was never starvation, nor were there massive roundups of average citizens.*

Still, the city did change measurably in the first year of the Occupation. For example, the cinema had never been so popular, yet before too long, lights would be turned up in the auditorium when Nazi newsreels were shown, to intimidate those who would laugh or hoot at them. Cafés, one of the few places where one could go for predictable warmth (churches having turned off their furnaces for lack of coal soon after the first harsh winter of 1940–41), were often frequented by Germans, in uniform and not. Cafés were also one of the few places one could go for a bit of privacy. From the seventeenth century onward, they had attracted police spies precisely because of their reputations for enabling private conversation about dissidence and revolt. The same pertained during the Occupation: real and potential resisters used them as mail drops and as places to hold discreet discussions about tactics. Care was taken, for one might be seated next to a German soldier or bureaucrat or, worse, a French collaborator and thus be seen or heard. This newly “uncanny” atmosphere persisted elsewhere, too. Streets that had been previously anodyne, e.g., Rue de Rivoli, Rue des Saussaies, Boulevard Raspail, even the Champs-Élysées, acquired a sinister aura because of official German presence. The same was true for certain quarters, such as the 3rd, 4th, 8th, and 20th arrondissements, known to be filled with “foreigners”—i.e., recent immigrants and expatriates—which were likely to be raided unpredictably.

The more expensive quarters, areas where many Germans had seized apartments and homes, notably in the 8th and 16th arrondissements and in Neuilly, had almost taken on the air of a neighborhood in Hamburg or Munich. In historian Cécile Desprairies’s census of private and public buildings “acquisitioned” by the Germans, a good third of her six-hundred-plus pages cover only three arrondissements: the 8th, 16th, and 17th, still today the most coveted of neighborhoods, while only about forty pages cover the Latin Quarter’s less affluent, more crowded 5th and 6th arrondissements.* Interestingly, for the nervous Parisian, the Left Bank (which included the Saint-Germain area, Montparnasse, and the Latin Quarter) was believed to be “safer” than the Right Bank, where the largest number of Jews, eastern European immigrants, and German personnel lived. This was more of an instinct than a fact. In his idiosyncratic memoir-cum-novel, Rue des Maléfices (published in English as Paris Noir; 1954), petty crook Jacques Yonnet describes how he, a spy for the Resistance, managed to stay one step ahead of the authorities by losing himself in the labyrinthine streets and neighborhoods of the Latin Quarter. Bars and cafés were his meeting places, his “offices,” even though he was fully aware of the presence of collaborators; one just had to be careful. The presence on the Left Bank of many lycées, several universities—notably, the Sorbonne and its various institutes—and such grandes écoles as the École normale supérieure and the École libre des sciences politiques (now the Institut d’études politiques de Paris) meant that there were thousands of young people in the area eager to establish their independence from any dominant ideology. This sense of shelter was mostly an illusion, yet the Left Bank retained its aura of safety from oppressive authority, of a “less German” Paris, throughout the Occupation.

In general, the architectural integrity of Paris was not nearly as marked by the Occupation as were the physical and affective qualities of living in the city. A large swath of the area around the grands boulevards, between the Avenue de l’Opéra and the Avenue de la République, was closed even to bicycle traffic. Other major avenues were barred or heavily guarded, but most remained accessible to Parisians, at least on foot. Few sites were renamed, though the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt did become the Théâtre de la Cité, and some street names were déjudaïsées—that is, “de-Jewed.” Métro stops kept their original names, though many were closed either for reasons of security or to serve as air raid shelters (abris) or storage facilities. As noted, the Germans constructed many ugly concrete bunkers and other defensive structures around their encampments and headquarters. There were even plans to build a new German embassy on the Place de la Concorde, but apparently Hitler never approved them. The Occupier did raze many of the shanties that surrounded Paris (where the poorest of the poor lived), in the zones created by Haussmann’s annexations of 1860. There was also substantial destruction by air raids in the near suburbs, where most of Paris’s industry and railroad yards were located. But the capital’s built environment was mostly left untouched by wary Occupation authorities. This fact reinforced the uncanniness: Paris looked the same, but it “had left the Seine.” The ville des lumières had become the ville éteinte (the extinguished city). It was a darker city—gray and brown, not to mention noir (black), were required adjectives to describe the absence of ambient light.

In his memoir, Un Petit Parisien (A Little Parisian Boy), the journalist Dominique Jamet describes coming of age during the Occupation and how buffeted his life was between the ages of six and eleven. He especially remembers how quickly Paris had become another city:

Paris without light, but Paris without cars, Paris without traffic jams, Paris without pollution, Paris without accidents, Paris without stoplights, Paris without noise, Paris made younger by the cleaning of its arteries where thrombosis no longer threatens, Paris, under its veil of soot and the calcified crust of its black facades, reveals its most beautiful, truest appearance, the larger perspective of its avenues made languid by good weather, returned to their proper proportions, the alignment of its palaces, of its houses, the curve of its streets, which have found again the purity of its lines.4

The city could be perceived in ways impossible since the end of Haussmannization; the original ideas behind the reconstruction of Paris, to project it as an imperial city, with attempts through a coordinated architecture to imply that Paris would never end, that it was eternal. This Paris could be glimpsed again during the Occupation. There are many references to a changed Paris, to one where sounds previously smothered under loud urban noises could be heard, where one could walk more safely because only bicycles clogged the streets, where walking itself imposed a new rhythm of urban consciousness. It is a bit ironic that Paris—hungry, tired, and embarrassed by its shortages—could still nevertheless show its “bones.” Its original beauty remained and provided occasional solace for those enmeshed in a strange, sinister environment.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, cities were increasingly being described as threatening, the blame going to the ravages of industrialism. No longer places to seek unfettered fortune, they became, in novels and essays of the period, sites of unhealthiness, physical danger, political instability, and immorality. And one of the most commonly cited reasons for these phenomena was the absence of light at night. Such lack of illumination was characteristic of most cities, and few offered as much vibrancy in the midnight shadows as the French capital. Paris had defined its very modernity, attractiveness, and pleasure in terms of the safety of its well-lit streets and boulevards. To live, then, in a newly darkened Paris, a city that had been known for its taming of nighttime, was unnatural and disorienting to both visitors and inhabitants. The unreliability of electricity and the need for defensive measures meant that streetlights were intermittent at best, absent most of the time. The headlights of the few automobiles running at night were covered with a blue material that let only a strip of light through. A constant darkness meant that one had to learn anew how to navigate familiar streets and neighborhoods. Tentativeness became a habit; everyone had a story about how someone had tripped, fallen into a hole dug by a construction crew, or bumped into someone while negotiating the murky streets. One writer described to a friend what it was like to look out a window and see not the Parisian glow but the much smaller, indiscriminately bouncing beams of flashlights (less frequent after batteries became impossible to obtain). He wrote: “You cannot imagine the little streets of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, Les Gobelins, the Canal Saint-Martin, the Bastille neighborhood, without any light except that of the moon! You can walk for hours without meeting anyone.… Despite the darkness and the disorientation I’m afraid of experiencing this evening in places that were so familiar to me, I still feel my way, though carefully.”5

One day in his studio on the Left Bank’s Rue des Grands-Augustins, the fretful Picasso noticed that his flashlight was gone. He flew into a rage, accusing his secretary, visitors, and servants of having misplaced it or, worse, filched it. He stormed around the apartment for hours, fuming and refusing to see visitors or to paint. He stopped speaking to any of those who lived around him. For Picasso, to lose a flashlight was to have to admit how much he and others had to depend on the device, not only to get around outside but also to get around inside. A flashlight was not just a tool, it was an embarrassing necessity, as important to living in occupied Paris as a bicycle. The day was one of the most tense his entourage had ever experienced, but the next was better: Picasso had found the missing flashlight right where he had left it.

Another urban characteristic, the cacophony of daily urban engagement—passersby, hawkers, street minstrels and performers, construction work, and especially traffic noise—was severely diminished during the Occupation. The patina of urban noise affords the urban dweller another sort of anonymity, a sensory cocoon that provides a feeling of protection from the interjection of unwelcome sounds. Urbanists often ignore inhabitants’ aural engagement with their city, but it is as important in how we negotiate a city’s complexities as our senses of sight and touch. Writers of the period, such as Colette, emphasize how quiet Paris became during these years. Sometimes the silence brought benefits, when pleasant sounds—birdsong, music—were able to reach Parisians’ ears. And there are many mentions of how clearly radio broadcasts could be heard (especially problematic for those listening to the BBC). But mostly, the new silence in such a vital capital must have been confusing and intermittently frightening. Police sirens were more menacing, airplane engines meant danger, a shout or scream provoked a more nervous response.

Dancing the Minuet

Despite all the signs, Parisians were still caught flat-footed by the surrender of their city, and it would be months before they realized what a military occupation really meant. A young Parisian wrote in her journal:

How those first days… have been disillusioning, sad, and different! To try to express, to render, this suffocating ambience would have only rendered it more insufferable.… More than ever, the “I’ve heard,” the “I’ve been told,” the “it seems that” are taken seriously. They are in effect useless, but they test the resistance that one has built up. In spite of oneself, one dreams, laughs, and then falls back into reality, or even into excessive pessimism, making the situation more painful.6

The time of year—late spring, summer, and fall—helped lull Parisians into a sense of well-being. Food was still easily available; despite the relentless shopping by the occupiers, the stores were still stocked, and there was no need for coal or large amounts of electricity. The Germans had immediately put France on Berlin time, so there were even more daylight hours available well into the autumn. Curfews were generally later and predictable, and the Métro was running after a brief stoppage. Apartment windows were being unshuttered as those who had left during the exodus returned (in fact, the state railroad system was activating more trains to accommodate the returning hordes, even offering free passage back home to Paris). Maybe this Occupation would not be so onerous. After all, suggests a historian of the period, once the Brits signed their own armistice or surrendered, life would return to normal. The Germans would go back over the Rhine, and a “new Europe” would bring order and prosperity:

To create a climate favorable to a productive colonialization by seducing [Parisian] souls appears to be one of the first concerns of the occupier. To place between the German authorities and the Parisians a screen that would mask, more or less totally, the important role the former was playing in this process was equally important to the Occupation. They intervened directly in our cultural life, but discreetly so, notwithstanding the heavyhandedness of some of their representatives.7

The German war machinery—panzers and paperwork—was quite happy to insist to the French and the world that their presence would be as unobtrusive as possible, except for political immigrants and Jews. Still, it was impossible to “miss” the Occupation if one stayed in Paris during that period. The Germans were visitors, wandering curiously with guidebooks in hand, who would not leave for home. They “were everywhere, and they had purposefully selected the most sumptuous buildings, the best-known mansions; they intervened, directly or indirectly, in all the city’s activities; people spoke, sotto voce, of the Gestapo, but they scarcely were aware of the inner workings of the machine that was controlling them.”8 This new administration of Paris was a confusing one, and not only to the occupied. The Reich’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, as well as the Gestapo, the Wehrmacht, and other military services, were all vying to control aspects of Parisian life and the French economy.* They were also competing for Berlin’s attention. The Occupiers—innocently and purposefully—collided and often duplicated efforts. Recently, the historian Max Hastings has succinctly addressed the contradictions that hampered German administration of both the Reich and its occupied countries:

There is a striking contradiction about Germany’s performance in World War II. The Wehrmacht showed itself the outstanding fighting force of the conflict, one of the most effective armies the world has ever seen. But its achievements on the battlefield were set at naught, fortunately for the interest of mankind, by the stunning incompetence with which the German war machine was conducted.9

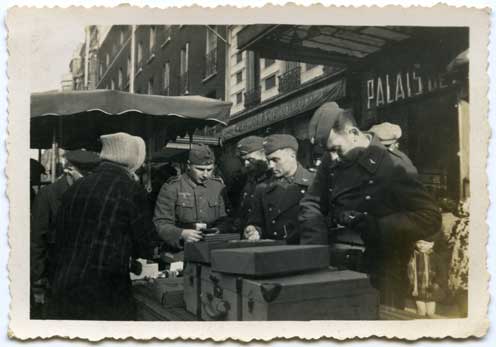

We’re only tourists. (Musée de la Résistance nationale)

The Germans were nothing if not planners. Even before the Occupation their spies had long been at work in Paris, and Berlin had been studying the public records of the city of Paris’s architectural office for months in advance. They knew who lived in which apartment houses, which buildings were publicly owned, and which were private. They knew the location of every bank, art gallery, record-keeping depot, insurance company, and warehouse. They had studied blueprints and site drawings so they knew which buildings had multiple entrances. They knew the sewer system and the underground railroad and even understood the labyrinthine nature of Paris’s mined-out limestone quarries. They knew the specialties and locations of all major hospitals and clinics. They had learned which lycées and schools had extensive playing fields. They had a list of all of the bordellos of Paris and had already selected those that would be reserved for their own men. They had decided which restaurants and which cinemas would be open only to German authorities. They had the names of every wealthy Jewish family and which bank vaults contained their most valuable belongings. They knew which works of art had been removed from which museums and in most cases where those works had been taken. They knew of the census that the French had taken of foreign immigrants. They knew the numbers of rooms that each hotel contained. They knew the telephone and pneumatic-tube systems of the city. They knew who had telephones and where the switchboards were. They knew the intricacies of the river that passed through Paris, its docks and warehouses.

This sight of the Occupier living and working in their city, rather than the much rarer scenes of force, continuously disturbed the Parisians. Appropriators of familiar spaces, the Germans made the City of Light unheimlich (uncanny) for its longtime residents. There was no “ordinary,” and as a consequence the Parisian had to take unfamiliar measures to deflect a regular interruption of daily routines and expectations. Many observers of this period—both French and German—remark that Parisians soon assumed a sort of blindness toward the innumerable uniformed men in their midst. Here begins the myth of Paris sans regard, the Stadt ohne Blick—the city without a face—discussed in the next chapter. Yet we must be careful not to assign a monolithic response on the part of the Parisian populace. Many Parisians benefited from the German presence in their city. Not all Germans were Nazi thugs; they needed entertainment, food, clothing, and other comforts, including human contact. For propaganda purposes, for morale, and for the economy (which the Germans had to support if they were to skim hundreds of millions of francs off the French GDP every month), Paris barely skipped a beat in maintaining a vibrant entertainment industry (films, theater, vaudeville, cabarets, bordellos, radio variety shows, even an incipient television industry). Horse racing was a major divertissement again by the second year of the Occupation; the fashion industry, even under severe material shortages, still prospered. The bimonthly German guidebook Der Deutsche Wegleiter für Paris included pages of advertisements for fashionable designers and what remained of luxury items in the occupied city.

Looking for a good deal. (Musée de la Résistance nationale)

Every major economic, political, and military unit needed a place to work and to collect; countless Parisian buildings were used for this purpose. The traumas of the Occupation were entombed in the apparent banality of these mostly Haussmannian edifices, clad in the pierre de taille (carved or freestone masonry) that gives Paris its character. The authorities chose most of these buildings, too, because they were conveniently located at the intersection of two or more streets, thus providing multiple entrances and exits. They served multiple functions: “The same spot could be a place of torture, of pleasure, or of business.”10 But no structure was too small or insignificant to escape Nazi attention. They even requisitioned newspaper kiosks to ensure the distribution of their newspapers and magazines. (Other kiosks, the significant remnants of Haussmann’s “street furniture,” were often removed for fear they might be too close to official buildings.) The military constructed concrete blockhouses at key junctions and before key buildings throughout the city. Massive underground bunkers were constructed under the streets and rail stations of the city. They set up warehouses everywhere, especially near major train stations, in which to store the household goods they had “appropriated” from Jewish and “foreign” families. These goods would be sent to Germany to replace what had been destroyed by Allied bombing.

The Germans and their outposts were in almost every Parisian quarter and neighborhood. Every district had an office of the Occupation authorities or an apartment building that had been totally or partially requisitioned by the Germans; the city was dotted with Jewish businesses and residences that had been seized. Wherever she looked, there was a reminder of France’s complete subservience to the Occupier. Hundreds of buildings were requisitioned or “Aryanized”; thousands of apartments were turned over to new owners, either Germans or their sympathizers. Later, changing the purpose of a building, putting a new sign on it, or even razing it rarely erased the memory of its former use, no matter how innocuous that use might have been.

Like the minuet, a dance with precise moves but little touching, the Occupation involved two parties—the Parisian and the German—trying to avoid stepping on each other’s toes. That does not mean that there were not strong feelings individually expressed on both sides. Small signs of resistance—teenagers on their bikes whistling when they passed Germans in uniform, graffiti on the city’s walls, stony stares—cropped up against the inevitable arrogance of the conqueror: pushing ahead in line, making bad jokes, speeding carelessly in their cars on the city’s arteries. Such early signs foreshadowed what was to become a much more bitter interaction.

Soon after the army and the bureaucrats arrived, German women auxiliary workers—Red Cross nurses, secretaries, telephone and telegraph operators—began to appear on Parisian streets. Dressed in gray uniforms, with perky little caps on their carefully coiffed heads, they soon became known as the “gray mice,” or “little maids.” They walked through the streets with the same patronizing purposefulness of their fellows, eschewing any of the stylishness that defined so many young French women, even in a time of austerity. Parisians gossiped about their “real” purpose, given the large number of men in the German contingent, but, at least for this early period, German couples were rarely seen on the street. These young women lived in hotels that were like dormitories (and even in actual dormitories, such as the one at the recently built Cité internationale universitaire, in the 14th arrondissement); they frequently ate in separate canteens and, like nuns, walked in pairs or groups while shopping. Their presence might have softened the image of the hard soldier whose main task was to impose order, but they also tended to remind the Parisian of the permanence of the German Occupation authorities.

Probably the first major adjustment, in July and August following the Occupation, had to do with automobile transportation. Parisian owners of large cars (in particular, models from 1938, 1939, and 1940) were ordered to take them to the Vincennes hippodrome, on the outskirts of the city, for evaluation and “purchase” by the Occupation authorities. Buses were transformed from gasoline power to wood and charcoal power (gazogène), which was provided by large containers atop the vehicles, giving them the look of some sort of humpbacked exotic animal escaped from the zoo. (The mature trees of some arteries had to be trimmed radically in order for these contraptions to pass.) New tires and retreads could no longer be sold to civilians; driver’s licenses were parsimoniously issued. Professions that had lived by the gasoline engine become dead ends: taxi driver, bus driver (many city and intercity bus lines were canceled or shortened), deliveryman, and moving man. The bicycle—soon de rigueur for anyone not walking—became even more prevalent, and in the Occupied Zone every one of them had to be registered; they carried small yellow tags on their rear mudguards. (After two more years of the Occupation, with an aluminum shortage, license plates would be issued in heavy cardboard and were no longer required to be posted.) It was obvious that bikes would be used increasingly for harassing the Occupiers, but there was no way to forbid them, or Paris would have ceased to function. Still, all bicycles were carefully monitored, and rules became more stringent: hands must be kept on handlebars at all times, feet on the pedals; no second riders; no latching on to passing trucks or cars; no riding abreast, only in single file.

One of the major mistakes made by Berlin was its failure to define its role in two key ways—a failure that would end up exacerbating the unpleasantness of the Occupation. First, it did not give specific guidelines to the Occupation authorities to do anything in Paris but “maintain order and security”; and second, it refused to clarify for the Vichy government its future in a Paris and in a Europe ruled by the Reich.11 Such lack of precision combined with the unique presence of a separate État français led to one exquisitely melodramatic episode that embarrassed key political figures—Hitler himself; Otto Abetz (the German ambassador to Paris); the prime minister, Pierre Laval; and Maréchal Pétain. It concerned the decision to return the remains of the King of Rome, Duke of Reichstadt, and only recognized son of Napoleon I (who designated him Napoleon II upon his abdication) to the Invalides, where he would lie beside his father. Arno Breker recalled the Führer gazing on Napoleon’s tomb:

Witnesses to this historical moment, we were secretly hoping and even waiting for Hitler to find words appropriate for the occasion and the site. Something absolutely unexpected then happened. He spoke of the Duke of Reichstadt, Napoleon’s son, whose remains were in Vienna. A magnanimous gesture of reconciliation with the French people seemed to him to be what the occasion demanded.… Hitler’s order was a gesture of reconciliation, but events did not allow it to find a positive echo from the French.12

This last sentence is an understatement, for the event caused the first serious contretemps between the German Occupation and the Vichy government.

Coincidentally, Pétain was at that moment in the process of reorganizing his cabinet with the aim of ridding himself of the oily, subversive Pierre Laval, a close confidant of Otto Abetz, Foreign Minister Ribbentrop’s man in Paris.* Laval had supported the idea of returning the ashes when Abetz mentioned it. (It remains unclear how much more Hitler had thought about his suggestion after he made it in June.) By mid-December, Laval had contrived for Hitler to send the following letter to Pétain:

Berlin, December 13, 1940

Monsieur le Maréchal, the 15th of December will bring the centenary of the arrival of Napoleon’s body at the Invalides. I would like to honor that occasion by letting you know, Monsieur le Maréchal, that I have decided to offer the mortal remains of the Duke of Reichstadt to the French people. Thus the son of Napoleon, leaving surroundings that during his tragic life were foreign to him, will return to his native country to rest next to his august father. Please accept, Monsieur le Maréchal, my personal esteem.

Signed: Adolf Hitler13

Pétain, for once, was incensed at the arrogance of the German leader. Informed that he was expected to be at the Invalides to receive the coffin on behalf of a grateful France, he haughtily refused: to appear under the Nazi flag, surrounded by German military, would have offended even the most neutral French citizens. And, to put it bluntly, Pétain couldn’t have cared less about Napoleon II’s ashes (the French use the term cendres to refer to the mortal remains of major figures, even when there has been no cremation). He had other things on his mind: getting rid of Laval, for one, and persuading the Germans to allow him to move his government from the backwater of Vichy to Versailles, nearer Paris, as the Armistice agreement had suggested. To the embarrassment of the newly fired Laval and Ambassador Abetz, Pétain, for once, stood his ground.

What followed was nearly comic, a combination of the ghoulish, the pompous, the hypocritical, and the amusing—one of the few events of the Occupation that can inspire a small smile. The heavy bronze coffin was taken from the Capuchin Church in Vienna, where the Duke of Reichstadt had lain for more than a hundred years next to his mother, Marie-Louise, grandniece of Marie Antoinette. (There were wags in Paris who asked, after the transfer had been announced: “Why move him away from his mother? Why not move them both? Or move Napoleon to Vienna—keep the family together.”) Placed on a special armored train, the coffin made the slow trip from Vienna to Paris through a freezing European winter. One Frenchman remembers that his father, a railroad worker, bundled him up and took him to the Gare de l’Est that cold morning to watch the train come in. His father asked his fellows when the young Napoleon’s body was arriving. “What Napoleon? We’re expecting an important train with the body of some German big shot, the Duke of Reichstadt.” As one historian has pointed out, the French knew more about the Duke of Windsor than they did Napoleon’s boy.

The heavy coffin, which had been surrounded inside the car by a small forest of Austrian pines, was placed on a special caisson that was pulled through Paris by the light of torches down major boulevards, along the icy Seine, past the Louvre, to the Invalides. The scene was right out of Leni Riefenstahl’s (Hitler’s favorite filmmaker) and Goebbels’s lugubrious performance manual: darkness, torches, slow pacing, cadenced drumming, all hints of ancient Teutonic tradition. This parade happened right after midnight, and, of course, there was no one in the streets, only the slowly pacing cortege, led and followed by military vehicles. It was wicked cold, with persistent sleet falling on the catafalque. When the parade reached the Invalides, the coffin was brought in by German soldiers, formally delivered to the elaborately uniformed Garde républicaine, who laid it at the chapel’s altar, where finally a tricolor flag was draped over the casket. (An exception had been made to allow the French flag to be used ceremonially.)

Somberly, an official placed at the bier a wreath from Philippe Pétain, chef de l’État français. But shouldn’t there have been one, equally ostentatious, from the Führer, whose brilliant initiative this had been? Indeed, a late night delivery had been made, before the chapel had been opened. A wreath with the name of Adolf Hitler prominently displayed had been left outside the gate. The story is that the wife of the Invalides’s caretaker saw it and quickly removed and burned it in her fireplace. In turn, her husband gathered the wires on which it had stood and buried them on the grounds. So there was no wreath from the magnanimous Nazi manager of this ghoulish farce.

The next day Parisian newspapers described the arrival and the disposal of the remains; soon there were long lines of French and Germans waiting to see the coffin. But overall, this meticulously planned spectacle had, as Pétain knew it would, little impact on the French. (“We asked them for coal and they sent us ashes” was a typically Parisian response.) An especially imaginative rumor, one believed by many, was that de Gaulle had been killed in the bombing of London and his ashes had been spirited to Paris, placed in the Duke of Reichstadt’s coffin, and were now resting next to Napoleon!

So the minuet had miscues and slipups. For about a year, until Germany invaded the USSR in June of 1941, both sides tried to follow the other’s lead, if suspiciously. As the summer months of 1940 passed, many Parisians found themselves increasingly preoccupied with figuring out how to meet the normal demands of everyday life. Larger questions such as resistance, political concerns about the new Vichy government, and philosophical notions about liberty were put aside in favor of worrying about finding nourishment, fretting about the million and a half French soldiers still in POW camps, and adjusting to new and less efficient means of transportation. But there were Parisians who had other, more immediate concerns.

Correct, but Still Nazis

Jacques Biélinky was born in Russia in 1881 and had immigrated to Paris in 1909, primarily to escape the anti-Jewish violence that was frequent in that part of Europe. He became a French citizen in 1927 (not that such a choice would help him escape deportation and death in the camp at Sobibòr in 1943) and began to write for Jewish papers, both in French and in Yiddish. When the Germans arrived in Paris, many Parisians were curious, angry, or neutral. But Jews knew that the web of Nazi racism was encroaching on them in one of the continent’s most progressive cities. Within two months of their arrival, the Germans began a census of all foreigners, “with the assistance of the owners of apartment buildings, apartment managers, and concierges.”14 The effort made even French Jews apprehensive. By the end of September, the Vichy government had passed specific anti-Jewish ordinances defining “Jewishness” and setting up regulations regarding property ownership. From July of 1940 until December of 1942, Biélinky kept a meticulous journal of the effects of the Occupation on the complexly heterogeneous Jewish population of Paris.

The number of Jews in Paris at that moment is a difficult statistic to pin down, even given the intensive effort of the Vichy and German police to establish the aforementioned census. In general, we can work with these numbers: in October of 1940 there were about 150,000 Jews in Paris, and many more were coming daily from Alsace-Lorraine, from which they had been expelled. Of that number, about 86,000 were French nationals (though some, like Biélinky, had been citizens only since the early twentieth century), and about 64,000 were foreign immigrants, many of them recent. They spoke many languages and held varying degrees of allegiance to Jewish religious practices. They were mostly poor, but a significant number of them had businesses and other affairs that had brought wealth. The many synagogues of Paris ranged from the modest to the opulent, and there were definitely social prejudices on the part of some groups toward others. In fact, many of the poor Jews had convinced themselves that the rich ones would be the targets of Nazi looting and arrest—certainly not they, who had nothing.

Biélinky’s diary gives us a detailed account of life in the first year of occupied Paris as he tried to gauge the dangers for Jews, which were harder and harder to ignore. His journal is a cross between an anthropological study of an urban environment under duress and an analysis of the status of Jews within the capital. Strangely enough, he found that in the beginning, Gentile Parisians gave Jews and their situation little attention, showing disinterest rather than hatred or scorn. He hears almost no anti-Semitic remarks while waiting in shop queues; he even learns that patrolling French police occasionally kept right-wing thugs from intimidating Jewish students and merchants.

There were definitely targeted ordinances—Jews could not sell their buildings or apartments, Jewish musicians were fired from classical and popular orchestras—but on the whole German soldiers themselves seemed unconcerned with those whom their government considered their greatest mortal and moral threat. For instance, in the Rue Buffault, in the working-class 14th arrondissement, a German garage was right across the street from a synagogue. Jews were at first skittish about going to worship, but the Germans barely took notice of them; there were no incidents. When there were a few anti-Semitic outbursts in a soup line, German soldiers would at first protect the Jews.

Despite the bright yellow signs on the outside of Jewish shops, reminding potential patrons that their owners belonged to the hated race, their business grew. Was it because of Parisian solidarity, or was it a form of Parisian resistance? Biélinky did not know, but perhaps it was both, and the examples reflect how difficult it is to suggest a seamless tableau about Parisian anti-Semitism and apathy. For the most part, non-Jews seem to have ignored the regulations imposed on their Israélite neighbors. Even visiting Germans and their wives shopped in those stores, and, unbelievably, some Catholic shop owners put the same yellow signs up because they seemed to attract more customers than other types of advertising. One Jewish woman said that the fact that her parents’ restaurant had a yellow sign meant they never had to worry about German clients. Should a German soldier walk in obliviously, her parents would point to the sign (in German as well as French); he would mumble an apology and leave.

That does not mean that the Germans did not do their dirty work. Rumors were rampant, and Parisian Jews were always waiting for another shoe to fall. Biélinky heard of Jewish bookshops being raided and apartments being targeted with alacrity and precision. Rabbis enjoined their congregants not to talk politics at worship, and not to stand around outside the synagogue drawing attention. Still, our optimistic (or, at least, hopeful) journalist remarked as late as May 19, 1941, that despite increasingly inclusive dragnets targeting Jews, perhaps the worst would not happen in Paris: “On the day of mass arrests of Jews for internment, around one hundred Jews—especially artists and intellectuals—were arrested at the city hall of the 14th arrondissement. Outside, the French crowd, very Aryan, violently protested against these arrests.”15 But Parisian solidarity and sense of justice would not be enough to keep these roundups from increasing, nor would the Wehrmacht, though not unhelpful in some of the SS’s actions, be able to stop their fanatical brethren from trying to remove every Jew, French or foreign, from the streets of Paris.

“To Bed, to Bed!”

In another part of the city, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (known universally by her last name alone), France’s best-known woman writer, a feminist and a gifted narrator, was also interested in recording what was happening in her beloved city. She had decided to return to Paris after the exodus and, like Picasso and her close friend Jean Cocteau, who lived nearby, to remain there. She did not wander very far from her enclave: the Palais-Royal. This former palace, built by Cardinal Richelieu in the seventeenth century, is located in the center of Paris, just a stone’s throw from the Louvre. The site of some of Paris’s most idiosyncratic shops, the building had several apartments on the upper floors; although they were not grand, they had the cachet of location. The Palais-Royal was to Paris what Paris was to the rest of war-ravaged Europe: an island of relative peace and calm despite being in the 1st arrondissement, among the most infested by the German presence. The Occupation authorities had requisitioned about two dozen hotels for offices and billeting in that district—among them the capital’s most famous establishments: the Ritz, the Continental, the Meurice, the Lotti. This geographically small neighborhood contained the Ministries of Justice and Finance, the Louvre, the headquarters of the Banque de France, the Police Judiciaire, on the Quai des Orfèvres, and the Palais de Justice, on the Île de la Cité. It encompassed the luxurious Place Vendôme and the popular Les Halles. And it was home to the Orangerie and the Jeu de Paume museums (which Göring would visit more than twenty times during the Occupation). But the Germans did not lay their hands on the Palais-Royal: no hotel in the neighborhood was requisitioned, nor were any apartments or any businesses appropriated. For years, Colette and her husband, Maurice Goudeket, a Jewish journalist, lived at 9 Rue Beaujolais, in a small apartment she affectionately called le Tunnel. One of France’s best-known chefs, Raymond Oliver, ran Le Grand Véfour restaurant, located on the ground floor, under Colette’s apartment. High-ranking Germans and French collaborators often lunched and dined there, and Oliver would on occasion send dishes to his friend upstairs. From time to time, a German military band would play in the garden, and military personnel could be found there playing chess outdoors. But the wall around the old palace’s garden seemed to have kept the Occupiers at a distance.

Colette and her friend Jean Cocteau in the gardens of the Palais-Royal. (Serge Lido/Sipa Press/Sipa USA)

The Palais Royal and its secluded gardens

At her second-story window on the northern edge of the enclave, Colette would sit on her chaise longue and write her letters, stories, and newspaper columns. (During the war, she composed “Gigi,” the story that would bring her wide international fame.) From October of 1940 until her husband’s arrest in December of 1941, she wrote a series of articles for the collaborationist newspaper Le Petit Parisien. As one of her critics says: “This collection… is not among those that would have allowed Colette to pass into posterity.”16 Yet it provides an important glimpse of the first reactions of Parisians to the sudden arrival of the German occupiers. To the chagrin of many who were less sanguine about the invader, Colette wrote a sort of advice column to her women readers, suggesting how to make do during this difficult time. The columns make little reference to the political nature of the Occupation; after all, they were being published in a newspaper controlled by German and Vichy censors. But they do let us know how soon the Occupation began to wear on Parisians and in what ways many of them coped. Twin concerns dominate her pieces: winter cold and the paucity of good nourishment. Colette suffered much from an arthritic hip that kept her inside her apartment. She could barely navigate the steps down to the shelter during air raid warnings and rarely ventured into the Métro because of the stairs down to the tracks. Yet she maintained, at least in her columns, an optimism that would, as a friend said after the war, be seen as a sort of heroism, a keeping of one’s sangfroid during difficult times. She repeated her commonsensical mantra: despair, sorrow, and penury teach us how to live better than do joyous moments, and things would get better. “I have known happy Paris too well to worry about unhappy Paris,” she famously wrote.17 Colette had always challenged in her work the bourgeois hypocrisy that defined elite Parisian society, and this comment is a perfect example of her devil-may-care attitude about the Occupation.

Her columns also introduce another subject in need of more attention: the role of women in Paris during the Occupation. More than a million and a half French soldiers had been captured in just over a month, most of them spirited away to Germany. They would be released in dribbles for the next four years, used as bargaining chits by the Germans to ensure, through blackmail, as much quiescence as they could from the French population. The large absence of men (in stalags, in hiding, or working abroad) meant that Paris became a significantly feminized city, yet another major consequence of the presence of a masculinized other. Women, then, had to leave the hearth and venture out into the world to find jobs, food, and companionship if they were to survive physically as well as psychologically. Raising children became more burdensome; the temptation to accommodate oneself with the German Occupier became harder to resist, less ethically severe. Colette suggests in her columns that Parisian women should follow her strategy: lie low, find food, and stay at home as much as possible. “Au lit, au lit!” (To bed, to bed!), she half seriously offered as advice. What most of her readers did not realize, of course, is that in addition to her physical infirmities Colette had the anxiety of worrying about her Jewish husband, a journalist, too, who had been “relieved” of his job at the daily Paris-Soir by the Germans as soon as they arrived. Her neighbors and nearby merchants offered him a hiding place every night if one were needed, for they knew that the police—French or German—arrived while you were still in your bed. One young woman on the floor above even told Maurice that he should come “jump in bed” with her if surprised by a raid. Sure enough, Goudeket was arrested by the Gestapo in December of 1941 and imprisoned for two months. Colette’s prestige and the respect German ambassador Abetz’s French wife had for her enabled his release in February of 1942. For the rest of the war, they lived anxiously, awaiting another ominous knock on their door.*

From her second-floor window prospect, Colette knew that there were stories “out there,” as her readers tried to adapt to a new set of daily occurrences. For example, just because the Germans were everywhere did not mean that crime had disappeared: one of her best friends was mugged in one of the Palais-Royal’s arcades. And because she religiously believed that to eat meant more than to nourish the body—it meant nourishing the imagination as well—one had to know the black market and other sources (friends in the countryside, for example) intimately in order to obtain impossible-to-get foods such as garlic, cheese, and pork. Colette also wrote of how much more sensitive she and others had become to sounds, both human and nonhuman—loud, unexpected sounds as well as quiet ones, which had become audible because of the diminution of traffic in the empty streets—sounds such as the occasional gunshot kept her from concentrating on her work. (Children in the garden, with their constantly popping cap pistols, did not help.) But she still refused to leave Paris for the country; the city, even in distress, continued to provide inspiration for her work, which dealt with how people love and live under seemingly depressing circumstances. Even though her connected friends kept her and her husband, Maurice, protected from further Nazi harassment, and even though she finally gave up writing her newspaper articles, the anxiety never totally disappeared.

Colette and others also took notice in their journals and memoirs of the subtle changes that occurred in daily social interactions between Parisians as well as between Parisians and their German “visitors.” A new sort of awareness had to be developed: checkpoints for papers were more frequent; looking ahead as one walked familiar streets became routine. There was a reorientation of the habitual use of the senses as Parisians made their way through a changed city. One’s hearing had to adjust to the unfamiliar, disorienting silence caused by the absence of traffic noises. Memoirists even mentioned that the sound of wooden—as opposed to rubber, a material that was rationed—soles pounding on the pavement allowed one to track the number as well as the speed of passing pedestrians. (In December of 1942, the singer Maurice Chevalier would introduce his song “La Symphonie des semelles de bois” [The Symphony of Wooden Soles].) Sight and touch were more often put to use as citizens became aware of what their neighbors were wearing, how their fellows were coping with the new restrictions the war economy had produced, from foodstuffs to textiles. Private motorized transportation having been radically restricted, densely packed public transportation became an environment in which Parisians of all social and economic classes were aware of the body odor of their compatriots. As a historian of everyday life in this period has convincingly posited: “To break a plate, tear a pair of pants, choose one café over another, speak with any neighbor can have grave consequences. The simplest gestures in a time of peace are no longer at all trifling in an occupied, pillaged, destroyed country.”18

Wit, humor, and a sense of the absurd soon become expressions not only of a sense of fatalism but also of resistance. Jokes and pranks (some of them cause for imprisonment) were soon part of the Parisian response to the invaders. Perhaps the most repeated joke of the period managed to knead enemy, victim, and ally into a single confection:

Hitler, searching for a way to invade England, calls in the chief rabbi of Berlin and asks him how Moses parted the Red Sea. If he can get that information, the Führer will end his harassment campaign against the Jews. The rabbi answers: “Give me a week, Chancellor.” Returning a week later, the rabbi announces that he has both good news and bad news. “Well,” insists an impatient Hitler, “do you have the answer or not?” The rabbi replies, “Yes, sir—it was the staff Moses always had with him that had the power to create a path through the waters.” Demanded Hitler, “Where is it?” Answered the anxious rabbi, “Well, that’s the bad news. It’s in the British Museum.”

A more ghoulish joke:

A Parisian reports to his friend a rumor that at 9:20 the previous night, a Jew attacked and killed a German in the Métro. He even ate part of his entrails, including his heart. The friend says with a laugh, “You’ll believe anything you hear, Pierre.”

“But it’s true!”

“No, my friend: it’s impossible.”

“Why?”

“First, Jews don’t eat pigs; second, Germans have no heart; and, third, at 9:20 everyone is listening to the BBC.”

An Execution in Paris

Yet humor only went so far. On Christmas Eve day in 1940, Parisians awoke to find the following notice pasted on kiosks and in Métro stations:

The engineer Jacques Bonsergent, of Paris, received a death sentence by the German military tribunal for an act of violence toward a member of the German army. He was shot this morning.

Paris, 23 December 1940

The Military Commander of France

What strikes us about this announcement is that it does not refer to any political affiliation, nor does it imply that Bonsergent was a terrorist. He was simply a young French engineer. Parisians were left to wonder whether he had struck a blow for France or whether he had acted out of personal pique.

It remains unclear today as to what happened in the streets abutting the Gare Saint-Lazare that Saturday evening, November 10, when Bonsergent was arrested; official reports and recollections vary. What we can be sure of is that a group of young Frenchmen, coming out of the station after having gone to a wedding in the country, ran into a group of German soldiers heading back to the barracks after a bibulous evening. Liquored up, the groups confronted each other, or bumped into one another, or exchanged a few comments. Bonsergent’s friends skedaddled, but he was caught by the Germans and immediately brought into the lobby of the nearby Hôtel Terminus, where he was held for the military police. He refused to give the names of his comrades, and he was hustled off to Cherche-Midi Prison, on the Boulevard Raspail, in the 6th arrondissement.

Unfortunately for Bonsergent, two significant events occurred between his rather routine arrest and his surprising death sentence. The day after he was caught, World War I Armistice Day, students rallied on the Champs-Élysées for the first—and, during the Germans’ reign over Paris, the only—large popular demonstration against the Occupiers. The exodus had wound down, families were returning to their city, and schools were reopening, though later than normal. Arguments were increasingly heated as a wide range of French men and women—pacifists, “wait-and-see” holdouts, anti-German patriots, Communists, and even vigorous supporters of the new Vichy regime—worried more and more openly over the military and political debacles they had just seen take place. Many frustrated and angry young Parisians saw the annual celebration of Armistice Day as the perfect moment to show French solidarity against the German presence in their city. Primarily at the initiative of high school and university students, the word passed quickly that a large crowd would march up the Avenue des Champs-Élysées to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe and, on their way, lay flowers at the statue of the great prime minister Georges Clemenceau, leader of France in late 1918, when Germany had had to sign its own armistice. Sometime on November 8, the only “call to arms” that historians have been able to track down was distributed in lycées and universities across the city:

Student [sic] of France! November 11 remains for you a National Holiday. Despite orders from the oppressive authorities, it will be a Day of Memory. You will not attend classes. You will go to honor the Unknown Soldier [at the Arc de Triomphe] at 5:30 p.m. 11 November 1918 was the date of a great victory. 11 November 1940 will signal yet another. All students are in solidarity that France must live. Copy and distribute these lines.19

Having heard rumblings of such an event, the Free French in London encouraged, by way of the BBC, a big turnout. (Subsequent investigations have left doubts about how many Parisians actually heard the BBC’s call to demonstrate.) Estimates vary, but perhaps as many as one thousand to three thousand young people showed up, first to lay wreaths at the statue of Clemenceau and then to continue their march up the wide avenue to the Arc de Triomphe.* “The Marseillaise,” by then outlawed by the Vichy government, was whistled, sung, and played on improvised instruments. Many students carried two fishing poles, called gaules, signaling with their deux gaules solidarity with de Gaulle, the increasingly well-known general who spoke to the French frequently from London.

But the Vichy government had heard of the possible demonstration and had warned the Paris police and the Germans. As a result, the authorities were waiting for the crowd. Initially surprised at the numbers, the police soon realized that the group was not organized; composed of many small groups of friends, classmates, members of youth organizations, and so forth, the march was easy to disrupt by police action. At first the French police seemed to have everything under control, but soon the crowd felt the stern hand of German police and soldiers who charged the groups as they approached the Arc. The demonstrators scattered. Some were protected by merchants who opened their doors; other merchants and bystanders pointed out the miscreants. Those who could not escape felt the blows of police billy clubs and fists. The authorities fired shots, and several youngsters were wounded. As always, among the victims were the innocent. I was told of one mother, out shopping, who was caught in the crossfire and shot in the thigh; she would have bled to death had not bystanders waved down a car to take her to a hospital. How many of the manifestants were killed, if any, has never been confirmed.

The other significant event that had an effect on poor Bonsergent’s fate was that Philippe Pétain and his Vichy ministers had insulted Hitler by not showing up to receive Napoleon’s ashes on December 14–15, 1940. The commander of occupied France, General Otto von Stülpnagel, under intense pressure from Berlin for being too soft toward such incipient expressions—nonviolent and violent—of noncompliance and rebellion, decided to make an example of young Bonsergent, and he did. The French had their first “resistance” hero—one with the solid and popular name of Jacques and a patronymic that implied decency and military rank.

By midwinter of 1940–41, days had indeed shortened; surprise arrests had become more frequent; friends and colleagues had disappeared into the Parisian prison system; sentences had been meted out for purported offenses toward the Occupation authorities; but no one had yet been put to death for them. The authorities’ poster had announced not only the death of a young professional but also the beginning of the end of the “correct” minuet that had theretofore defined the Occupation.

A minuet demands exquisite timing and subtle appreciation of the movements of one’s partner. It permits a limited number of steps; it suggests intimacy without allowing it. It is the perfect dance for strangers or almost strangers; whether or not a second dance follows depends on the comfort established with the moves and signals of the first. Minuets were meant to introduce casual acquaintances at large gatherings; if nothing came of one dance, then the disappointed twosome sulked patiently and waited for better partners. Yet in this case, for one of the minuet’s participants, the dance was not one in which there could be a voluntary separation. The darkness that blanketed Paris was increasingly both tangible and intangible. More lights were soon to be extinguished, and the minuet would cease.