Chapter Six

The Dilemmas of Resistance

In war as in peace, the last word goes to those who never surrender.

—Georges Clemenceau1

Quoi faire?

In July of 1940, not long after the arrival of the first German troops in Paris, a mimeographed flyer was stuffed into apartment mailboxes, slid under doors, and placed on café chairs. Created by Jean Texcier, a journalist from Normandy, “Tips for the Occupied” was one of the earliest signs of French resistance to the foreign occupier. These ironic suggestions introduced some of the formative themes of the Occupation just as the German bureaucracy was eagerly setting it up. Texcier lists thirty-three conseils, or tips. Among them:

• Street vendors offer them [German soldiers] maps of Paris and conversation manuals; tour buses unload waves of them in front of Notre-Dame and the Panthéon; each one of them has a little camera screwed to his eye. Don’t be fooled: they are not tourists.

• They are conquerors. Be polite to them. But do not, to be friendly, exceed this correct behavior. Don’t hurry [to accommodate them]. In the end, they will not, in any case, reciprocate.

• If one of them addresses you in German, act confused and continue on your way.

• If he addresses you in French, you are not obliged to show him the way. He’s not your traveling companion.

• If, in the café or restaurant, he tries to start a conversation, make him understand, politely, that what he has to say does not interest you.

• If he asks you for a light, offer your cigarette. Never in human history has one refused a light, even to the most traditional enemy.…

• The guy you buy your suspenders from has decided to put a sign on his shop: MAN SPRICHT DEUTSCH (we speak German). Go to another shop, even if he doesn’t speak the language of Goethe.…

• Show an elegant indifference, but don’t let your anger diminish. It will eventually come in handy.…

• You complain because they order you to be home by 9:00 p.m. on the dot. You are so naive; you didn’t realize that it’s so you can listen to English radio?…

• You won’t find copies of these tips at your local bookshop. Most likely, you only have a single copy and want to keep it. So make copies for your friends, who will make copies, too. This will be a good occupation for the occupied.2

Texcier had intuited early that resistance did not have to be violent, that standing against the occupier did not require a grenade in one’s hand. The flyer wittily and temporarily answered the question “Quoi faire?” What to do? What is the protocol for daily living in a city occupied by a formidable and arrogantly victorious enemy? The massively defeated French found themselves in a quandary. Had not their government signed an armistice with the Germans? Had not a war hero, the estimable Maréchal Philippe Pétain, become chef de l’État français? Were not the Germans acting “correctly,” at least now, at least toward the average French person? Of course it was a bit galling that German signs were popping up all over Paris, that certain avenues and boulevards were closed, that private automobiles had been requisitioned, that a palpable sense of entitlement was emanating from the thousands of German soldiers and bureaucrats assigned to the city. But most Parisians believed that to be a temporary price of defeat once the fighting and bombing had stopped. Texcier had captured the mood of the moment: be polite but unwelcoming; the Germans were not tourists, but they would be leaving soon. No one dreamed in midsummer of 1940 that more than 1,500 days would pass before Parisians would be free of their hereditary enemy.

French resistance against the Nazis has been asked to serve crucial functions in that nation’s collective memory. After the liberation of the country, the myth that a large majority of the French population from the beginning actively had opposed the Occupation was important in tamping down serious civil disorder, as the political right and left once again fought for control of a new government. The myth was also necessary to salve national pride over the breakthrough defeat of 1940 and in order to earn a place at the table with the European Allied powers—the USSR, the United States, and Great Britain—as they decided the fate of postwar Europe. In fact, this myth served to postpone for a quarter of a century deeper analyses of how easily France had been beaten and how feckless had been the nation’s reaction to German authority, especially between 1940 and early 1943. Finally, the myth of a universal resistance was important to France’s idea of itself as a beacon for human liberty and as an example of the courage one needed in the face of hideous political ideologies.3

French historians continue to tie themselves in knots as they work to define and explain the Resistance. They parse the term itself, arguing about when the small r became a capital R. They use anthropological, psychological, and cultural methods to identify and categorize varieties of opposition to the presence of victorious Germans on French soil. They struggle over the antithesis of resistance: is it cooperation, appeasement, acceptance, accommodation, collaboration, or, worse, treason? Is resistance a moral or a political choice? Could one not resist in good conscience? Is nonviolent resistance really resistance? The historical and popular narratives surrounding these questions are complex, gripping—tortured, even—often misleading, and sometimes mendacious. Add to this the fact that many résistants were not French citizens but immigrants, often Jewish, and that saving Jews was not a stated aim of “official” resistance organizations, and the story becomes even more complicated and blurred.* 4

One recent French historian has meticulously analyzed how long it took for the idea of the Resistance to take hold in France. Public opinion moved slowly from a comfortable, benign belief in the leadership of Maréchal Pétain, even with early evidence that his political colleagues were anti-Semitic, anti-leftist, and even pro-fascist. His revered persona obfuscated political distractions, at least for the first year or so of the Occupation. What resistance there was, especially in the Unoccupied Zone (that part of central and southern France still controlled by the Vichy regime), was limited to a propaganda campaign to keep up French morale:

The power of the myth of Pétain in that part of France that remained “free” [that is, unoccupied] limited the Resistance to the use of propaganda [instead of force]. Before dreaming of fighting again, they had to convince a public largely comfortable with defeatism and attentisme [waiting it out]. Success in this direction was slow to come.5

To judge, even today, can lead to ethical headaches. We must always keep in mind that we know the outcome of the Second World War; our judgments are influenced by that reassuring knowledge. No such comfort was available to those faced with the devastating fact of massive defeat and military occupation.

Other historians have argued that the term resistance has entirely different connotations when applied to different parts of occupied Europe. Writes Jean-Pierre Azéma:

Given that the Nazi occupation is founded on a racist as well as an imperialist ideology, the logic of occupation in western Europe diverged from that of the east. In the part of Europe peopled by Slavs, the conqueror not only annexed but expulsed, colonized, and exterminated those it considered subhuman: resistance became a vital imperative. In the west… resistance was not seen as a means of surviving.… One could “accommodate,” and many did.6

Using German terms, Azéma argues for the difference between actively, often violently, “withstanding” or “standing against” a foreign host (Widerstand) and quietly maintaining a state of nonacceptance, of “resisting”—that is, refusing to concede to the fact of and even ignoring the German presence (Resistenz).7 To explain how exquisite some of these distinctions can be would take us further from our subject—resistance in Paris—but it is necessary to be aware of how important the concept was and continues to be to French identity.

Perhaps the origins of this complexity began in the radio war that occurred in June and July of 1940 between two French military men, an upstart “temporary” general (général à titre temporaire) speaking on the BBC from London and a venerable, widely respected Maréchal de France (the highest military rank) speaking from Bordeaux and later from Vichy. These speeches, or appels (calls to action), introduced the three major terms that would come to define this debate during and after the war: résistance, occupation, and collaboration. The speakers were, of course, the relatively unknown fifty-nine-year-old Charles de Gaulle (he had been promoted to brigadier general during the brief Battle of France and would later be demoted and cashiered by the Vichy government, although he would continue to use the title of general) and Maréchal Philippe Pétain. One of the earliest uses of the term resistance had entered official parlance when Churchill wondered aloud after Dunkirk if there would be anyone left in France to “resist.” Then, in his famous national allocution of June 17, 1940, after he had hastily called for armistice talks, Pétain himself, assuming authority over a defeated France, used the term: “Certain of the affection of our admirable army, which still struggles with a heroism worthy of its long military traditions against an enemy superior both in numbers and in arms; confident that by its magnificent resistance [that army] has fulfilled its obligations toward our allies,… it is with a deep sorrow that I tell you today that the fight must end.”8 Of course the concept has an entirely different meaning in Pétain’s discourse from the one it will later take on, but it is interesting that a day later, in his rapid radio response, the famous “Appel du 18 juin,” de Gaulle picked up the word: “Whatever may happen, the flame of French resistance must not go out; it shall not go out.” And four days later, in another BBC address, without using the term specifically, he reiterates: “Honor, common sense, patriotism demand that all free Frenchmen continue the struggle wherever they are and however they might.”9

Punctilious analysts of de Gaulle’s speeches and of his politics in these early days of a Free France differ on what he was calling for. Did “free Frenchmen” refer to those who were in the empire’s colonies or abroad rather than to those already under the yoke of the Germans? Or did the term refer to all French who refused to accept German domination, within and without France? The reason this question arises is that de Gaulle, throughout his four years in exile, harbored a very conflicted view of “internal resistance,” that is, of the anti-German activities of organizations and individuals within France. It would take him almost three years, until mid-1943, to bring most of those independent resistance groups under his bureaucratic command. His greatest fear was that the best organized of them all, the French Communist Party, would offer strong political alternatives to his already developing vision of postwar France. De Gaulle’s anti-Communism was not ambivalent; the organizational and ideological strength of the French Communists, especially after Hitler invaded the USSR in June of 1941, would preoccupy him until and after the end of the war.

One other point should be made about the reputation of French resistance. Overwhelming attention by journalists and military historians—both then and later—to the June 1944 Normandy invasion helped to elevate the idea that there was a powerful secret army at work in France during most of the Occupation.* It can be argued that the Resistance was probably never as effective as it was in those few hours and days preceding and immediately following the Allied invasion. Indeed, Operation Overlord needed every scant advantage it could find, and Eisenhower made canny use of the armed and unarmed units in France to help disrupt German response to his massive invasion, one that could well have been stymied or pushed back into the Channel several times before July of 1944. In fact, Ike was quoted widely as estimating that the war had been shortened by two months because of the French resistance fighters. In his postwar memoir, Crusade in Europe, he wrote: “Throughout France the Resistance had been of inestimable value in the campaign. Without their great assistance the liberation of France would have consumed a much longer time and meant greater losses to ourselves.”10 But that estimable success was an anomaly; for the most part, the intra-France resistance of the years 1940–44 definitely harassed, but was in no way permanently detrimental to, the Occupying forces, either in northern France or, after the Wehrmacht occupied it in November of 1942, the southern part of the country. As one of our best historians of both the resistance and the Resistance, Matthew Cobb, writes: “For most of the war, the vast majority of the French did little or nothing to oppose Vichy and the Occupation.… Less than two per cent of the population—at most 500,000 people—were involved in the Resistance in one way or another.”11 On one hand this could seem a rather significant number (out of a population of about thirty-eight million), especially if it had been an organized, deftly led force of armed and unarmed men and women. But it wasn’t. This number includes independent, often individual, actions during almost five years of the Occupation, supported by some French citizens but also criticized by many of them as well. Resistance attacks brought reprisals, horrible ones, prompting the Free French government to warn from London that disorganization, lack of coordination, and the emphasis on only short-term goals could be detrimental to the central purpose of liberating France.

De Gaulle, himself an army man, distrusted the independence and freewheeling nature of resistance groups while recognizing that they did have some positive effect on the morale of a people still recovering from the humiliations of 1940. Without a doubt, there was a strong, courageous, and tenacious minority who did resist. About one hundred thousand men and women whom the Germans and the Vichy government designated as “terrorists” may have died—in battles, in camps, or as a result of executions—during the war, but the public was decidedly split over the efficacy of their actions and was often angry at their valiant but frequently foolhardy deeds.12 Toward the end of the war, as the Germans were slowly retreating through France toward Germany, the audacity and cunning of the so-called maquis (the guerrillas who lived off the land) caused apprehension among ordinary German soldiers and often brought brutal reprisals.* Yet the Germans and their Vichy allies had been very effective in keeping the various resistance organizations at bay throughout the Occupation; their intelligence services, relying heavily on the French themselves to denounce their fellow citizens, were remarkably successful.

Resistant Paris

To limit discussions of moral and violent resistance to the Occupier to its effectiveness at undermining the German war machine misses an important point: the decisions and actions taken by French men and French women, and by new immigrants, against the Occupation (especially of Paris) did keep the Reich and their Vichy allies on the alert and did send a message to the world that Paris was not being benignly held prisoner. Everything from whistling at Germans while they marched in step to printing and distributing dozens of anti-Nazi tracts to throwing grenades into German crowds to assassination: these actions, though often uncoordinated, created an atmosphere of tension and a sense that one’s life was not totally in thrall.

Roger Langeron was concerned enough about the possibility of a violent resistance to the arrival of German soldiers to warn his men to be especially alert. As chief of police, he feared that hotheads would set off a merciless response from an overconfident German army. But the exodus of May and June, 1940, had cleared Paris of three-quarters of its inhabitants, and early summer was a time when the schools were closed. The doldrums of the season did the rest. The Germans found a quiescent, even polite population, and the only reactions they had to parry were an occasional rude remark or pointed stare. Until the early fall of 1940, all seemed in order. By October, though, Paris had regained a good deal of its population and some of its élan, and a palpable feistiness stirred its inhabitants. The shock of seeing Germans, in uniform and in mufti, walking casually or marching confidently throughout the city’s arteries began to fade, and resentment began to build. On public holidays, an occasional French flag could be seen or a whistled “La Marseillaise” heard. At first the Germans took these mild expressions of resistance to their presence calmly; one report sent back to Berlin even mentioned that in general the French were, in these first few months, “correct,” “loyal,” and “courteous.”13 Soon, though, the strain began to tell. Unable to ignore these scattered but recurrent protests (they correctly intuited that small signs of disrespect could presage a more vigorous resistance), the MBF, the German military administration of Paris, demanded that Chief Langeron put a stop to the impudent practices of the mostly young Parisians who mocked their occupiers. Otherwise, they threatened, there would be strong repercussions.

But this was easier ordered than done. The Wehrmacht was not a police force, and its generals resented having to keep civil order in Paris while having to maintain military preparedness.14 They increasingly relied on—and put enormous pressure on—the Parisian police department (which on paper reported to the Vichy minister of defense but which had significant independence from the central government). Soon these police officials, as well as mayors and prefects, were receiving so many arbitrary, unpredictable, nervous, and furious phone calls from German officials that they asked collectively in mid-1941 for more formal, less idiosyncratic requests. At the same time, increased demands were coming down to arrest Jews, find escaped prisoners, ferret out downed Allied pilots, check out letters of denunciation, and investigate minor acts of sabotage. There is no doubt that many in the French police force responded with assiduousness, even eagerly. The Germans remained suspicious that French efforts at controlling the intransigence of their compatriots were not as vigorous as they should be; that there were Gaullist and Communist moles throughout the force (indeed there were) and that the bureaucracy’s pursuit of Jews was unenthusiastic. The apprehensiveness shared by both the Vichy police and the Germans grew in intensity just at a time when the Germans needed complete and enthusiastic cooperation: the invasion of the USSR in June of 1941 had drawn the best-trained and youngest soldiers from France to the east. As a result, manpower had to be husbanded, and excessive demands were placed on the French authorities to do the repressive work of an occupying force. So even though there was no formal resistance early in the Occupation of Paris, individual acts of disrespect, insolence, and rudeness were taking their toll on Zusammenarbeit (working together—the German version of “collaboration”).

As early as the fall of 1940, the first organized team of Parisian resisters was created among the curators and administrators of the Musée de l’Homme, the anthropological and natural history museum situated on Trocadéro Hill, site of the 1937 international exposition, overlooking the Eiffel Tower. They were especially astute about publishing and distributing anti-Vichy and anti-German tracts, including five numbers of a little paper named Résistance. These tracts called on French patriotism to encourage resistance against the Occupier; they also included news of the war gathered from English and Swiss radio stations broadcasting in France. They were successful at helping downed pilots escape back to Great Britain—forging papers, lodging them with sympathizers, and passing them beyond borders. But within a few months, a French spy in their midst would denounce the group; its members were arrested, and eventually executed in early 1942.

De Gaulle’s June 18, 1940, appeal had little military or political impact, but it did give those young people in France, especially in Paris, a name to throw up on the walls, a name to pit against those of Hitler and Pétain. Most French might barely have heard of de Gaulle, but nevertheless they began to adopt him as a symbol of a nascent French resurgence against the Germans and their Vichy lackeys. By early 1941, his was almost a household name, especially in Paris. Soon the words Vive de Gaulle and depictions of his adopted symbol, the two-barred Cross of Lorraine, began appearing insolently on Parisian doors, inside public urinals, and on Parisian sidewalks. Little by little, the upstart general was, mainly through the force of his amazing will, becoming the symbol of resistance throughout France and its colonies. For his part, Churchill found de Gaulle impressive though obdurate, but he had nowhere else to turn for a French leader who might keep the fight alive in the French empire. Roosevelt’s distrust of de Gaulle was even deeper; FDR persisted until his death in seeing him as a right-wing general only slightly less offensive than his former Vichy colleagues.

In chapter 3, we learned of the only major public demonstration that occurred in Paris during the Occupation: the manifestation on the Champs-Élysées on November 11, 1940, Armistice Day. Other, smaller “spontaneous” marches and gatherings were held throughout France, but they were carefully monitored and controlled. Hundreds of these protests were patronizingly called “marches by housewives” and were held in opposition to the cost of and scarcity of food. The authorities were concerned that such expressions of frustration could turn into general opposition, and, sure enough, some, particularly those in large cities, were actually organized by resistance groups, especially the Communists. One was planned in mid-1943, on Paris’s Left Bank, near the Place Denfert-Rochereau. There stood a huge grocery store, part of the popular chain Félix Potin, with as many shelves empty as full. Appearing to lead a “spontaneous” event (almost like today’s flash mobs), Lise Ricol-London jumped onto a trestle table just as the store’s doors opened. Several accomplices threw hundreds of leaflets into the air as she called out to frustrated Parisian housewives:

De Gaulle’s Cross of Lorraine. (© Roger-Viollet / The Image Works)

The Occupation, with its cortege of misfortunes, restrictions, [and] crimes, has lasted long enough!… It is time to act! The French must refuse to work for the German war machine. By so doing they expose their lives and those of their families to Allied bombing.… Women! Stop your husbands, your sons from going to work in Germany. Help them hide, to escape to the countryside, where they can use their hands.… It is the moment to begin an armed struggle against the Boches [i.e., “Krauts”] in order to boot them from the country. The Second Front will soon arrive. Liberation approaches! Vive la Résistance, vive la France!15

Although she was attacked by Potin salesmen and others, Lise managed to escape the police. But she left behind evidence of a fiercely patriotic, and fiercely feminine, Parisian resistance, one that would grow slowly during the final eighteen months of the Occupation.

Resistance, especially this sort of hit-and-run strategy, is much easier in a city than in rural areas. Cities are, as Hitler and his cohort recognized, primed to stymie a rigid system of controls. As we have seen and will see, the metropolis offers many boons to those who would resist authority. First is the gift of anonymity. Strangers in cities are not immediately noticed; neighbors may be likely to pick out aliens, but the city provides so many covers for an individual that he or she can “pass,” often with audacity. There are also many places to hide in a city, many shortcuts, hidden and public, that allow an individual to escape quickly when pursued. We have already seen how porous apartment buildings can be. The subway system—in fact, all public transportation—provides secure ways to lose oneself and one’s pursuers. But the advantages of moving in a crowd, of jumping on and off transportation, outweigh the dangers of being trapped in a dead end when being checked or pursued. In addition, an old European city such as Paris is a labyrinth of streets, alleys, and byways, many unknown to foreigners no matter how carefully they study Michelin maps and Baedeker guides. And the capital offered a maze of sewers, Métro tunnels, and abandoned quarries that provided the same sense of protection as a countryside’s forests, ravines, and mountains do.

Paris, too, was dotted with many very public sites—such as cemeteries, large churches, flea markets, parks, river quays, marketplaces, large restaurants, and cafés—that could all serve as private meeting places for not-so-innocuous conversations. As well, the demographics and social personalities of neighborhoods can provide a sense of solidarity eminently useful to those on the run or seeking refuge.

The city itself has many entrances and exits: train stations, ports, and highways. The Germans did try to build barriers and controls to check vehicles at all the portes (major entrances) of Paris, but alternate routes were quickly and cunningly found. The Seine, which divides Paris, was a major resource for those who would escape the police; passengers could hide on barges as they glided through the city or be deposited at urban ports along with the cargo. Paris is a small city, about thirty-four square miles (not including its two large forested parks, the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes), and can easily be traversed on foot in a day, north to south or east to west. This would seem an advantage to the Occupier, but with a population of about two million, easy access to the suburbs, and—despite Haussmann’s great renovations of the late nineteenth century—a labyrinthine street layout, it was not a metropolis conducive to mass surveillance. It had a very large student population and an equally large immigrant population, both of them sympathetic to resistance or resentment toward an occupying army. This “shadow” citizenry, themselves anxious about discovery, served often as protective coloration for others hiding from the authorities. As a result, cells of resistance began to develop almost immediately once the fact that Germans were to be in Paris for a long time began to percolate through its inhabitants’ psyches.

The mimeographed tract was an early sign of nonviolent resistance. By the end of the Occupation, dozens of these one-to-four-page “newspapers” had appeared on the streets of Paris. Their distribution was only one challenge for their editors. First, paper had to be found, and large amounts of it had to be hidden from authorities who were already seeking to control its allocation. Virgin stencils were priceless, and because they could effectively produce only a few hundred copies, they had to be replenished constantly. Most important, mimeograph (or ronéotype) machines and printing presses had to be “borrowed” or stolen and moved from safe house to safe house. The noise associated with printing machines was another problem; isolated apartments and the basements of shops and apartment houses were used, but they were searched with increasing attention by the authorities. One prominent editor hid a small printing press in his apartment; soon he heard that he had been denounced, so he and a friend dismantled it and put its pieces in their pockets and briefcases. Making several trips to the Seine, they threw the pieces into the fast-flowing river. When the Gestapo arrived, there was no press, no sign of ink or stencils, and no ink on the hands of the editor or his friends. They nonetheless arrested the printer and questioned him for several days before he admitted that he had thrown the infernal machine into Paris’s river. At that confession, surprisingly, the police let him return home. It was as if they were more afraid of a wandering printing press than of the man who had wanted to use it.

Some writers wanted to do more than print tracts and news sheets with names like Pantagruel, Résistance, and Valmy (site of a great victory over the Prussians in 1792). One of them was Jean Bruller (a.k.a. Vercors). Bruller, as noted earlier, was the author and publisher of Le Silence de la mer (The Silence of the Sea), perhaps the best fiction ever written about passive resistance. To publish a hundred-page story was going to take more than a mimeograph machine; Bruller needed a printing press. He first sought out a printer who had access to paper, but he did not want to print the small book. Once he had a commitment for the paper, enough for three hundred copies, Bruller inquired about other printers who might help. His supplier asked him to return in eight days. Bruller was not too concerned, because the manuscript was still in his hands and he could always claim, if denounced, that he was going to use the paper for printing something innocuous. Eight days passed; he returned to the first printer. “I’ve found a press for you. Let’s go,” said his new collaborator. Soon Bruller found himself outside Paris’s largest hospital complex, the Pitié-Salpêtrière, on the Left Bank, just southeast of the Gare d’Austerlitz. This hospital was then and had been for a century one of the most respected in Europe.*

The Germans, knowing a good thing when they found it, had already appropriated the Salpêtrière as a major emergency and convalescent hospital for their military. Wehrmacht banners and the German swastika were everywhere evident when Bruller arrived; dozens of uniformed German officials were scurrying through the campus. What are we doing here? the author must have wondered. But just across the street was a small printing shop where invitations, announcements, and calling cards were produced. Its clackety-clack activity was barely heard over the constant comings and goings of German ambulances and sirens, and it was here where the most famous story to come out of Occupied Paris was printed. Bruller still had to find glue and cardboard for the book’s covers and men and women to sew together the printed fascicles. He did. The result was the first book published by a clandestine press in Paris, a press he named Éditions de Minuit (Midnight Publications), which would go on to publish about twenty-five works during the Occupation. After the war, it would publish the writings of luminaries such as Samuel Beckett, Marguerite Duras, Alain Robbe-Grillet, and others. (It continues to publish today.)

But some felt that more aggressive measures should be taken against the Occupier. On a hot August day in 1941, in the Barbès-Rochechouart Métro stop, not far from the Gare du Nord, a group of young partisans were trying to be inconspicuous while waiting—not for a train but for a German military officer, any German officer. Finally a naval ensign, dressed in the whites of the Kriegsmarine, arrived, and as a train pulled in and came to rest he started to step into the center, first-class car, reserved for him and his companions. As he placed his foot on the threshold of the car, a twenty-two-year-old Frenchman—who would be later known all over Paris as Fabien (the code name of Pierre Georges) and, subsequently, as Colonel Fabien, leader of the Resistance—pulled out a pistol and fired two shots into the back and head of the young officer, Alfons Moser.* Both names would soon be known throughout Paris. Moser was the first German officer to be shot publicly, in daylight, in France, and with his killing resistance against the Occupation had taken a decisive turn: the result would be a much more oppressive surveillance in the large cities of the Unoccupied Zone and more vigorous punishment, including executions of hostages, meted out by the Germans.

Such violence against the Germans became almost commonplace beginning in 1942. A résistant remembers a late spring night, probably that year, along the Quai d’Orsay, on the Left Bank. This was the upper-class area near the Ministry of Foreign Affairs where many German officers worked diligently at keeping the city calm. Undiscovered, two young men had been walking along the quay at the same time for a week, trying to discern a pattern of comings and goings as the Germans left their offices for their apartments or hotel rooms. On this evening, the two were sauntering along, glancing from time to time at the river, talking loudly, nonconspiratorially. Their mission: to obtain a firearm, the most precious and rarest possession of any resistance group. Soon, as they had expected, they heard the assertive sound of a booted officer coming up behind them. They kept walking beside the swift-moving river. The boots approached and then passed them. Pulling a blackjack and a hammer from their pockets, they leaped on the unsuspecting officer, beat him down, took his pistol and two ammo magazines, pocketed them, and ran down a side street, not stopping until they were blocks away. It would be, if they were lucky, hours before the German’s body—for he must have died from the double blows—would be found.

Such events had unpredictable and predictable consequences. One never knew how the German authorities would react. Would they shoot a dozen hostages? Would they change the curfew? Would they close down the neighborhood in which the attack had occurred and arrest all Jews and immigrants they could find in a roundup? For the sake of one pistol, an entire area and the many lives within it might be disrupted. On the other hand, the Germans would feel more vulnerable, less willing to go out alone when armed and in uniform. Not a few Parisians would be pleased that such efforts, though small in the scheme of major events, would remind the Occupiers that they were never going to be comfortable in the City of Light. Weighing ethically and practically the consequences of violent action became common practice as the war dragged on.

Bébés Terroristes

Harrassment of the Germans began almost the day they arrived. For the most part, the perpetrators—pacifists, anti-fascists, pro-Communists, Catholics, Jews—were in their teens or early twenties. This makes sense in a way, since youth do not have jobs to protect or families to provide for. The German-Soviet Pact, signed in 1939, right before Hitler attacked Poland, had hamstrung the most organized anti-fascist political group, the French Communist Party.* All members of the party had strict instructions not to attack the Germans, which gave the latter a year in which to set up an effective policing strategy with their Vichy allies and to concentrate on other challenges to their new order. By the late fall of 1940, de Gaulle’s message—about “continuing the struggle” and reminding the French that a battle may have been lost but the war continued—was getting through, especially to the most ungovernable of Parisian residents, high school and university students. The graffiti that promptly appeared on the walls, the whistling and hooting at German soldiers, the papers and tracts that were published and distributed—these activities were almost all the work of adolescent Parisians. Beginning in the winter of 1940–41, the first “battle” was initiated between the Occupier and Parisians: the Germans referred to it as the V-aktion; the French as “the war of the Vs.” Scrawled in chalk over walls, café chairs and tables, official posters, Wehrmacht directional signs, and especially on Métro walls—indeed, on almost any flat surface—were Vs for victoire, often appearing with de Gaulle’s Cross of Lorraine. German propaganda offices immediately appropriated the angular letter as an abbreviation of Victoria, a sign of German success on all fronts. (The Germans appropriated the Latin term, since “victory” in their language, Sieg, begins with an S.)

As Adolf Hitler looked down on Paris from his perch on Montmartre during his brief visit in June of 1940, he would have seen a large casernlike building to his right, visible in photographs of that moment. That structure would be one of the most vibrant centers of resistance during his army’s occupation of the city: it was the Lycée Rollin. With more than two thousand young male students, including those in middle school (collégiens) and high school (lycéens), it was one of the largest schools in Paris,* located in a neighborhood filled with the “degenerates” that Nazi propaganda had been fulminating against for almost a decade:

Almost a third of the inhabitants were of foreign extraction: Poles, Ukrainians, Russians, Romanians, Armenians, North African Arabs, and Berbers… Among the refugees, the Jewish community from eastern Europe was the largest. Paris was a sort of “new Jerusalem.” As a consequence of the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire, Sephardic merchants from Turkey and Greece had established themselves in Montmartre. Tailors, furriers, cloth merchants had created the Saint-Pierre market at the base of Sacré Coeur, just a few meters from the Lycée Rollin. German Jews began to arrive in the early thirties.16

Nevertheless, thousands of German soldiers visited the nearby Boulevard de Clichy, Place Pigalle, and Rue Lepic every weekend for four years, so the youngsters of the neighborhoods knew well and close up the haricots verts (green beans).

The political complexion of the Lycée Rollin ranged politically from the right to the left, but it earnestly leaned more leftward. The politicization of the student body, and of many of the one hundred or so professors, had begun well before the defeat of 1940 and the Occupation itself. The 1930s in Paris had seen street riots between supporters of neo-fascism, and the right in general, and young Communists and Socialists, especially after the election, in 1936, of the first leftist government since the nineteenth century, the Front populaire, led by the Jewish politician Léon Blum. And then there had been the Spanish Civil War, between the elected Republicans and the right-wing rebel Nationalists under Francisco Franco, a war that divided French political opinion deeply. When asked when she had joined the French resistance, one young Frenchwoman answered:

In 1937, when I saw on the walls of Paris photos of children massacred by Nazi aviators; when my parents took into their home little Pilar, five years old, whose parents had been killed in Bilbao and who hid under a table whenever she heard a plane over Paris. We were a group of young lycéens, and we founded Lycéens de Paris, an anti-fascist movement that demonstrated against the French government’s refusal to come to the aid of the Republicans.… Our entry into the Resistance was for us the consequence of this earlier engagement. The same struggle was continuing.17

The civil war in Spain, which had ended in mid-1939, had sent thousands of Republican refugees to France. Many of them were former fighters, and they provided a ready-made cadre for military resistance to authority. They had experience in the preparation and distribution of propaganda, in sabotage, in military excursions, and were adept at forming clandestine networks. Their children wound up in the lycées and universities of Paris. So it was to no one’s surprise that the attack on Poland, the defeat of the Allied armies in 1940, and the massive occupation of France’s capital would serve as motivation for these youngsters to let the Germans know that they were not welcome in Paris. And they were often encouraged by the outspokenness and courage of their professors. Both the Germans and the Vichyists kept a close watch on these youngsters.

The Lycée Rollin was the only high school to change its name after the war; it is now known as the Lycée Jacques-Decour, the nom de guerre of a teacher of German, Daniel Decourdemanche. One day, as his students prepared for their professor’s arrival in the classroom, the door opened, and in walked the school’s principal. The students stood immediately. The room, filled with fourteen- and fifteen-year-old boys, was still; the principal almost never visited classrooms in session. One alumnus remembers what happened next:

The principal stood on the podium. Gravely, a piece of paper in his hand, he told us: “Your German professor has been executed by the army that occupies our city. He asked me to read this letter to you.” Almost seventy years later, I can’t remember the exact details, but I do remember their general sense and the letter’s last words. He wrote us that when we heard this letter, he, Daniel Decourdemanche, would no longer be alive. That he was dying so that one day we would be free men. The principal slowly folded the letter and, after casting a glance over the whole class, left the room. Our temporary professor had to ask us to be seated. In that class, students had many different political views. Some were Pétainistes, others Gaullists; there was even a collaborationist who, later, would sign up with the Legion of French Volunteers against Bolshevism. Many were just preoccupied with their continuing hunger. Silence followed the principal’s remarks. How could that professor, whom we had seen just a few days ago chatting with his colleagues, no longer be alive? For the first time, all of us, in a state of disbelief, were suddenly and forever aware of the horror of war. Amazingly, not one of the students denounced the principal to the authorities! Courageously, he had risked his own life to give us students a lesson in dignity, in patriotism.18

Adolescence is a telling filter through which to analyze the Occupation. The unpredictability of adolescent judgment, actions, and responses must be the bane of any authority endeavoring to enforce order and predictability on a populace. A typical narcissism imposes itself on the adolescent, an almost compulsive need to separate oneself from a comfortable environment—an urge, if not a desire, to create a more personal and private world. The result can often devolve into secrecy vis-à-vis one’s parents; impatience with curfews and other limitations on time, space, and forms of amusement; and a commensurate disregard for even the most anodyne authority figures. There is a thirst for an attenuation of dependence yet an almost erotic need to form new affective relationships—often quasisecretive—as counterweights to the parental and familial ones weakening. In addition, there is an intellectual awakening, a moving away from the imposed teachings and beliefs of one’s parents and mentors, and often a simultaneous search for other, nonparental adults to fill in for those psychologically rejected. This makes adolescents especially susceptible to recruitment for “adult” enterprises. A new confidence in physical energy and ability emerges, too, accompanied by an urge to progress into new public and private spaces. It is no wonder, then, that an urban adolescent, finding himself under the thumb of a foreign occupier, is confused, resentful, and exhilarated all at once—or intermittently.

It was not too long before various organizations began assertively appearing in opposition to the Occupier. Eventually they would be unified under the umbrella of Forces unies de la jeunesse patriotique. But before that attempt at unification, the teenagers of occupied France called themselves the Jeunes chrétiens combattants, the Bataillons de la jeunesse, the Jeunes protestants patriotes, the Fédération des jeunesses communistes, the Front patriotique de la jeunesse, and on and on. There was often tension between these groups and those organized by more mature résistants, as the latter felt that lack of coordination, enthusiasm, and independence were detrimental to an organized resistance. Yet the adolescents were everywhere, and they kept up the spirits of those against the Occupation, especially in its early years.

One of the most extraordinary of these youngsters was a boy named Jacques Lusseyran. A student in the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand, situated on the Left Bank near the Collège de France and the Sorbonne, Jacques realized, at the age of sixteen, that unlike his placid parents and their friends he was not ready to acquiesce to this new “normality”: “I was no longer a child. My body told me so.… What attracted me and terrified me on the German radio was the fact that it was in the process of destroying my childhood.… To live in the fumes of poison gas on the roads in Abyssinia, at Guernica, on the Ebro front, in Vienna, at Nuremberg, in Munich, the Sudetenland and then Prague. What a prospect!”19 Jacques’s “uneasiness was more intense than the uneasiness of people full grown,” so he and a small group of friends began meeting to figure out how they could “resist.” The group named themselves the Volontaires de la Liberté and selected Jacques as their leader. It was his job to decide who could be trusted to join their group. But Jacques Lusseyran had been blind since the age of eight. The confidence that his school chums had in him was based in part on the way that he had handled that handicap as a schoolboy; they were also confident that the Germans would never suspect that a blind boy would be a chef de la Résistance.

For almost two years, until they were betrayed by another school chum, the group’s membership grew from a dozen to more than five hundred, and at one time Lusseyran could call on five thousand Parisian youngsters to distribute tracts, hide printing presses, compose copy, act as lookouts, and support other resistance groups. The tenacity of this group of youngsters, their clear-eyed belief in liberty, their hatred of the Germans and their acolytes the Vichy supporters, stood as a model for other resistance groups, though as Lusseyran estimates in his memoir: “Four-fifths of the resistance in France was the work of men less than thirty years old.”20 One of the main tasks of this group of youngsters was to encourage those other French citizens too hesitant to take a stand against the Occupation. Lusseyran insisted that his newspaper was not a political document but rather a “way of spreading passive resistance. Most of all we made it clear that there was an active Resistance at work, one that was growing from day to day. [Our membership] was invisible to our readers… The only sign it could give at that stage was our two-page printed sheet.”* 21

A little-known novel by Roger Boussinot, Les Guichets du Louvre (The Louvre’s Portals), takes as its subject perhaps the most familiar and despairing event of the Occupation, the massive arrest of Jews on July 16–17, 1942, primarily by French police. Boussinot’s autobiographical fiction reminds us that Paris had acquired a new topography for all its citizens (not just those especially sensitive to German presence, e.g., Jews and political refugees). A Gentile French student, packing up to return to his home near Bordeaux for summer vacation, learns from a friend on the fringe of the resistance that there will be a roundup of Jews on the Right Bank that very day, the infamous July 16, 1942. His friend suggests that if the young man and others like him were immediately to go to the targeted neighborhoods, they might each save someone by leading him or her to and through the guichets (the small gates through which one enters the Louvre complex from the Rue de Rivoli) onto the Pont du Carrousel and then across the river to the Left Bank, which was felt to be safer, less “German,” and more open to refugees than the Right Bank. The implication is that the river has demarcated what had become in effect two Cities of Light. Says the narrator: “On July 16, at about 4:00 a.m. in a Paris still asleep, buses with their bluish headlights left barracks, military camps, and depots and, under the curfew, started toward the neighborhoods of Belleville, Saint-Paul, Popincourt, Poissonnière, and the Temple.”22 All these neighborhoods were filled with Jewish families and businesses. Young policemen had been brought into Paris from the provinces to do the dirty work of rounding up Jewish families, and Boussinot depicts them as innocent tourists, visiting Paris for the first time: “The glances of the gendarmes… seemed to see nothing and only lit up when they recognized a public monument: then the kepi-covered heads would almost all lean forward together, trying to catch a glimpse of the top of the Eiffel Tower, or the Obelisk, or to follow the passing of the elevated Métro above the trees.”23 Yet as with Hitler’s tour that had preceded theirs by two years, their apparently innocent gaze hid a devastating project. Jews were in danger because the French, not the Germans, were on the hunt.

The young student decides, impulsively, to take up his friend’s challenge and sets out to cross the river:

I don’t know why, but crossing the Seine was disorienting for me.… From the Latin Quarter to Montparnasse, the Left Bank was as familiar to me as the streets of Bordeaux, or almost, but the Right Bank seemed to me the true capital, immense; I barely knew the big boulevards over there. Alone, immobile under the narrow and cool vault of the Louvre’s central portal, I was suddenly aware of a new feeling—of throwing myself into an adventure for which I was not prepared—a feeling of nervousness, of danger, even of anticipated failure.… I am still a bit away from where the roundup was supposed to be taking place, but perhaps because I’m alone, because everything is so quiet, the whole area seems to be a cunning trap, covering the occupied city like a hostile chill.24

Once “over the river,” he finds a Jewish girl a few years younger than he and saves her from being caught up in the pitiless dragnet. Soon, to avoid capture, the two youths are forced, as they move surreptitiously through a sinister environment, to find new uses for previously innocuous doorways, cafés, stairways, Métro entrances, concierges’ loges, shops, and the narrow streets of the Marais.

It was like a game of cat and mouse that lasted almost three hours in a labyrinth of streets that I did not know and where we often lost our way; in courtyards, rear courtyards, at the entrances, and especially on the staircases of apartment houses, always accompanied by this agonizing sense that we were alone in the world and that the police were everywhere—but with one advantage: the cats did not know that we were mice.25

On that sad day, most of the city’s buses (the familiar green-and-cream vehicles Jews had ridden every day to work and back) had been commandeered to take them to the Vélodrome d’Hiver, a massive indoor bicycle-racing track on the Left Bank, and thence to Drancy and other concentration camps near Paris—a very cynical trick. The city’s transportation systems are essentially closed to our two protagonists, for the Métro has become dangerous as well, their entrances guarded by the police and used as traps to capture unsuspecting Jewish travelers. So the youths have to walk from the Marais to the Louvre, and with care. They use public subway maps, posted outside stations, to find their way, but these maps are essentially useless for clandestine movement through the city. Ultimately they have to rely on their spontaneous and cunning use of the available spaces of the Parisian streets to make their way eventually to the guichets of the Louvre and from there to the Pont du Carrousel, bringing them to the Left Bank and some safety. Despite the fact that they have become emotionally close during their three-hour escapade, the girl decides to turn back, to find her family, and the boy, disappointed, gets on the train that takes him home to Bordeaux. This is a quite remarkable historical novel, one in which the very restrictions that the Germans used to keep people apart provide a nearly erotic atmosphere that inexorably pulls two of them close to each other. The absence of a happy ending only underlines the sorrow that pervaded the city of lovers during the Occupation.

Boussinot did not have an easy time getting his novel published in 1960, fifteen years after the war. In an afterword that he wrote to the 1999 edition, he places the blame for this initial censorship on the sensitivity of French memory. Few wanted to think about the Occupation and its embarrassing moral compromises. Another reason for the hesitancy to publish was the book’s ambiguous ending. The Jewish girl decides to return to the Right Bank, to seek succor from the Union générale des Israélites de France (the UGIF), an organization approved by the Vichy government and the German Occupation bureaucracy. We now know that this organization partially served as camouflage for an insidious attempt at separating immigrant Jews from French Jews, and often, purposely or not, served the racial policies of the government. But perhaps more significant to the unofficial censors of Boussinot’s work was the response of the unwittingly courageous young Gentile after his offer to accompany the girl to the Left Bank is politely refused: “I said nothing. And yes, I admitted it: let her leave now, go wherever she wanted, and leave me alone. I was tired of the whole thing. Tired of her. Tired of having to decide, to walk, to argue, tired of being afraid. Tired of the heat, of the police, of still being in Paris, of not being comfortable in my own skin. Tired of the Jews.… Don’t forget how young we were!”26 This honest memory would have touched the nerves of French readers in the early 1960s. Being in the underground, even for a day, was not a game. Everyone who made that decision had to consider his career as a student or an employee; he or she had to think of the effect on his or her family. The Germans soon put up posters that warned that any arrested “terrorist” would be responsible for having all male members of his family arrested, deported, or sent to work for the Germans.

One man remembers what it was like to be an adolescent in such a troubling environment:

The reasons for being afraid and of being apprehensive every time we went out into the city were numerous. In the streets, ID checks and roundups were continuous, even more so because we were all old enough to be recruited for the STO [Service du travail obligatoire, the conscription of young men for work in Germany]. Once we put a foot outside, we were at risk of being stopped at any point. To make matters worse, our false documents were so obviously forged that they would barely pass even the most casual scrutiny.27

And another is even more succinct:

Fear never abated; fear for oneself; fear of being denounced, fear of being followed without knowing it, fear that it will be “them” when, at dawn, one hears, or thinks one hears, a door slam shut or someone coming up the stairs. Fear, too, for one’s family, from whom, having no address, we received no news and who perhaps had been betrayed and were taken hostage. Fear, finally, of being afraid and of not being able to surmount it.28

Such feelings of wanting to do something yet being afraid of painful consequences, meant living in constant anxiety; that is probably why, at the end of his novel, Boussinot’s adolescent protagonist, when asked at home in Bordeaux, “What’s going on in Paris?” responds: “Nothing.”29 Perhaps best just to lie low and, if one had to confront the authorities, try to forget it.

The Red Poster

The Vichy government and German censors controlled all the official press—daily, weekly, and monthly. Radio signals from London were successfully—but not completely—scrambled, and the strong signals from Radio Paris (the official station) sent continuous and biased information to a populace thirsty for news of any kind. Newsreels emphasized German advances and minimized the results of Russian, British, and American successes. The underground did not have access to these outlets, though the BBC did get on the air for a few minutes every night, and the Allies did drop millions of leaflets across France with messages of hope. Still, many independent and organized resistance groups risked imprisonment and worse to spread a counternarrative. One young Jewish boy would take his six-year-old sister with him all over Paris to distribute tracts that described how Jews were being treated; they passed right before the eyes of their wary enemies. And we have seen how paper, ink, and printing apparatuses were as sought after as arms. The underground groups still were able to print one-page newspapers or tracts in almost a dozen languages in addition to French: Spanish, Polish, Russian, Czech, Armenian, German, Romanian, and Yiddish. Yet the Communist Party believed that louder, more consequential actions would not only enhance their own reputation but also keep up the spirits of an increasingly tired, hungry, and depressed Paris. “Loud” and “consequential” meant violent action, coordinated and effective.

With the Grande Rafle (the Big Roundup) in July of 1942, attitudes changed radically for all those concerned—Germans, Parisian police, Jews (foreign and immigrant), Parisians in general, and resistance groups. We will in the following chapter learn more details of this giant dragnet, but one thing can be said now: the raid not only confirmed that no Jew was safe in Paris, it also made evident to other Parisians that the Nazi racist ideology, and its cynical support by the French police, could no longer be ignored. Finally, it radically changed the more hesitant immigrant resistance groups, who concluded that only force could meet force. A new “generation of anger” among young Jews and their Gentile friends was born overnight. And, at the same time, the costs paid by more aggressive résistants could no longer be ignored.

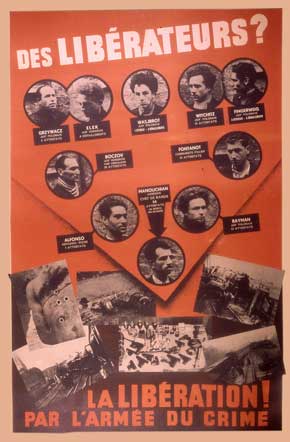

For Parisian passersby reading a garish affiche rouge (red poster), pasted everywhere on public walls, some names were almost unpronounceable, and certainly not “French”: Fingercwajg, Manouchian, Grzywacz, Wajsbrot. Unlike other posters that listed only the names of those executed by the Germans, this one had photographs of the alleged perpetrators, a first for the German propagandists. Against a dull red background, the poster showed portraits—mug shots, really—of shadowy, solemn, hirsute, “foreign-looking” faces. Also listed were their national origins: Polish, Italian, Hungarian, Armenian, Spanish, Romanian, and French. The bottom third of the sheet was covered with photographs of derailed trains, a bullet-pierced torso, a dead soldier, and a collection of small arms. The poster, printed in red and black, appeared on walls all over France in February of 1944. The terms Libérateurs? and Libérations? were written in very large fonts, implying that these “jobless bandits,” “terrorists,” “foreigners,” and “criminals” were unworthy of patriotic respect. The propaganda campaign was carefully organized; booklets were liberally distributed along with the posters. The accompanying single-page tract was even blunter than the affiche:

The Red Poster. (Mémorial de la Shoah)

HERE’S THE PROOF:

If some Frenchmen pillage, steal, sabotage, and kill…

It is always foreigners who command them.

It is always the unemployed and professional criminals who do the jobs.

It is always Jews who inspire them.

IT IS THE ARMY OF CRIME AGAINST FRANCE!

Banditry is not the expression of a wounded patriotism, it’s a foreign plot against the daily lives of the French and against the sovereignty of France.

It’s an anti-France plot!

It’s the world dream of Jewish sadism!

Strangle it before it strangles you, your wives, and your children!30

Who were these “foreign bandits” who had seemed to unleash all the paranoid fury of an occupying army and bureacracy that, by late 1943 and early 1944, were realizing that Germany was losing the war? The so-called Manouchian Group was an armed, Communist-supported team of urban guerrillas, part of the FTP-MOI (Franc-tireurs et partisans–main d’oeuvre immigrée, or Irregulars and Partisans–Immigrant Labor Force), which had been formed from mostly young Jewish independent operators who had been attacking Germans in Paris since the fall of 1942.* The Communist Party had decided that it would be more effective, and would bring more publicity to their own anti-German resistance, if these young men—and a few women—were organized in the manner of a military commando force, or a small, mobile combat unit.

Over the first six months [of 1943], the teams of the MOI carried out ninety-two attacks in Paris, which was under especially high surveillance at the time.… on April 23, grenades were thrown at a hotel near the Havre-Caumartin Métro station [in the heavily German-populated 9th arrondissement]; on May 26, a restaurant reserved for German officers was attacked at the Porte d’Asnières… On May 27 at 7:00 a.m., a grenade was thrown at a German patrol crossing the Rue de Courcelles… On June 3, on the Rue Mirabeau… a grenade was tossed at a car carrying officers of the Kriegsmarine.… The months of July, August, and September saw an upsurge of derailments of trains leaving the Gare de l’Est on their way to Germany.31

Finally, a coup de théâtre: on September 23, a small team managed to assassinate, in the cozy, German-preferred 16th arrondissement, General Dr. Julius Ritter, the head in Paris of the hated STO, which identified and drafted young French men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-two for forced work in Germany.

The Germans were caught off guard by this surge of violent attacks, and their troops were more and more demoralized as they watched “safe” Paris become a site for both discriminate and indiscriminate attacks against the Occupier. Enormous pressure was put on the French police, who created their infamous Brigades spéciales—about two hundred especially xenophobic and anti-Communist officers who volunteered to track down “terrorists” in the streets and neighborhoods of Paris. This office developed quite sophisticated means of following and setting up surveillance on suspected members of the underground. They were patient, even to the point of not stopping some attacks if they knew that bigger fish were still to be caught. They were experts in following their suspects, always working in twos and sometimes putting as many as four such teams on the heels of only one résistant. They disguised themselves as postal workers, bus drivers, even priests; one person caught in their snare reported that the team following him had even worn yellow stars! Once they arrested their suspects, they used the most brutal methods of interrogation, often to the embarrassment of their colleagues in other departments. After the war, many members of the Brigade spéciale were arrested, tried, found guilty, and put away for years, if not executed. In just a year, they managed to capture more than 1,500 young members of the Resistance, severely weakening the MOI.

When the MOI group was finally captured in November of 1943, after having been betrayed from within their ranks, they numbered twenty-three men and one woman. Interrogated and tortured for more than three months, they faced a hurried military trial, were found guilty, and were shot at the Mont-Valérien prison, outside Paris, in February of 1944. The one woman, Golda Bancic, a Romanian, was not allowed to die with her companions but was shipped to Germany, where she was decapitated in May of 1944.

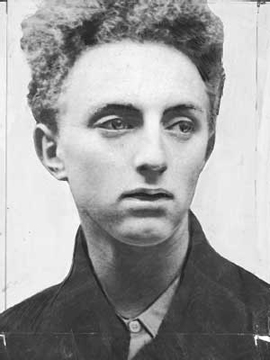

Tommy Elek. (Mémorial de la Shoah)

Besides its Armenian leader, Missak Manouchian, perhaps the best known of the armée du crime was the Jewish teenager, Tommy Elek. In photos, his boldly blond hair and direct gaze grasp one’s attention if only because of the effort made by the photographers to present the group as a bunch of unshaven, darkly hirsute, menacing foreigners. His mother, Hélène, kept a restaurant on the Rue de la Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève, in the 5th arrondissement, right behind the Panthéon and in the middle of the Latin Quarter. The restaurant, Fer à Cheval (The Horseshoe), was a favorite haunt for Tommy’s leftist friends and for students in general—and for the Germans. (The restaurant had three entrances and thus three exits—the Jews, as well as their antagonists the Germans—sought with care residences and places of work with more than one exit, so it was a perfect place for the transfer of weapons, tracts, and so forth.) Hélène knew German (she had been born and raised in Budapest, where German had been a second language for many), so the Germans felt welcome in a restaurant whose proprietor spoke their tongue with such skill. They marveled at how handsome her seventeen-year-old son was, how much he was the perfect example of an Aryan, with his blond hair and blue eyes. Of course they did not know that Tommy had been active in the Communist resistance for about a year. Imagine their surprise when he was arrested along with the rest of the Manouchian Group in November of 1943.

In fact, one of the best-known resistance acts in Paris had been devised and carried out by Tommy before the Manouchian Group brought him under their quasicontrol. He had taken a large book—his father’s copy of Marx’s Das Kapital—carved out its pages, and settled a dynamite bomb into it. He fearlessly took it to the prominent German bookstore Librairie Rive Gauche, on the Place de la Sorbonne. Placing the book on a table, he left and waited to watch it explode through the store’s plate-glass window, behind which were displayed works by German and collaborationist authors; an exultant smile creased his young face as customers left, coughing, trying to escape the fire that was raging. The attack was bold and very public; on the other hand, it was an example of what the Communist underground feared most: acts carried out by independent operators that would force the Germans and the French police to be more alert while having little effect on the war machine itself. Still, Tommy’s bomb drew much attention to the vulnerability of the Occupation forces in his city.

Hélène’s restaurant stayed open until 1943, when she finally had to put up a JEWISH ENTERPRISE sign. In her memoir, Tommy’s mother recounts how she came to learn of her son’s arrest. Tommy’s young brother, Bela, burst breathlessly into their apartment. Tears streaming down his face, all he could say was

“Tommy, Tommy.”

“What about Tommy, Bela? What about him?!”

Sobbing, he stammered: “They’ve put up a poster everywhere… with Tommy on it… and Joseph [Boczov, Elek’s friend and fellow résistant]… I saw it in the Métro, but here, too, in the street, they are everywhere.… They are all there, Maman… with horrible photos, cadavers, derailed trains.… For Tommy they’ve written ELEK, HUNGARIAN JEW, EIGHT DERAILMENTS.… They call them the army of crime.”32

Hélène Elek knew that Tommy’s fate was sealed, that he was dead or soon would be. She ran down her building’s stairs and outside to see the fateful poster for herself.

Tommy Elek’s last notes to his family, sent via the concierges of the buildings in which he had been hiding, were written a few hours before he was shot at Mont-Valérien in February of 1944. The poignant brevity of the notes, written by a barely nineteen-year-old youth, speaks not only to his courage but also to his confidence that he will have died for something larger than himself:

Monday 21/2/44

Dear Madame Verrier,

I am sending this letter of adieu to you in the hope that you will one day find my family again. If you see them one day, tell them that I did not suffer and that I died without suffering, thinking a great deal of them and especially of my brothers, who will have a happier youth than mine. I die, but I insist [they] live, for we will all be together again one day. Good-bye; may my memory remain in the hearts of those who knew me. May all my friends live, and my last wish is that they not be sad about my fate, for I die so that they will always live happily. Good-bye, and may life be sweet for you.

Tommy Elek33

In a second, even shorter letter to his friends, again addressed in care of a concierge (probably to avoid giving away addresses), he writes, again with laconic sensitiveness:

Dear friends,

I write you this letter of adieu to confirm, if need be, that I was pure in all my intentions. I don’t have time here to write long, empty phrases. All I have to say to you is that you mustn’t be sad, but rather happy, for better days are soon to come [car pour vous (viennent) les lendemains qui chantent, a very clear Communist innuendo]. Adieu; keep me in your hearts, and speak about me sometimes to your children.

Thomas Elek34

Hélène Elek was an extraordinary mother. She knew from the time he was sixteen that her elder son was resisting the presence of the Germans in Paris. She had worried but decided that the more she helped him and his leftist friends the more control she could have over his actions. Like any young teenager, Tommy was impulsive, naive, and often incorrigible, and his mother’s presence had given him some stability. He was proud of his Jewishness. Wrote Hélène: “Thomas knew perfectly that he was Jewish. He had learned it by looking at his thing. He was circumcised; I had had it done when we were in Hungary. Not to be religious, but because I thought it was healthier. And then, when he was five, he was in kindergarten in Budapest, and he had to announce his religion. He knew it well.”35 Hélène’s son told her almost everything, stories to make a mother faint. Street stops were becoming more frequent; anyone who looked like a foreigner would be searched even down to his genitals, but not Tommy—he just looked too Aryan. Elek recounted another story in which he and a fellow underground member were stopped on the Métro by a French cop. His friend was carrying a satchel containing ten grenades. “What do you have in that bag?” demanded the policeman. “Grenades,” answered the young man. “Smartass,” retorted the cop. “Be careful what you say; someone else would’ve arrested you.” Then he let them go.

Once Tommy’s photo appeared on the Red Poster and the name Elek became known to everyone, his mother had to go even deeper into hiding, especially because she began to work more diligently for the Resistance. In her memoir, published thirty years after the events, Hélène pulled no punches. Had it not been for the enthusiasm, as clumsy as it might have been, of her young son and his leftist friends, early resistance would have amounted to nothing: “And I can assure you that it was the left that resisted. I’m not saying that de Gaulle’s call to arms meant nothing; it was a good trick, in effect. But the Resistance was here, right here in Paris, thousands of young seventeen-to-twenty-year-olds who risked their skins every day.”36

For about a year after her restaurant was closed she managed to keep on the move (she wrote that she had found sixteen different hiding places for her family and was about to look for another when the Germans left Paris). She lived almost invisibly in Paris, thanks to the support of friends, Gentile and Jewish, and to her extraordinary sangfroid. She and her family were among those forty thousand Jews who were living in Paris, many with their yellow stars still affixed to their clothes, at the end of the Occupation. Given the zeal of the combined police forces of the Reich and of Vichy, this is an extraordinary number. Much of the credit for their survival is due to the courage of those people, Jews or not, who stayed with, went to the barricades for, and never gave hope up for the Resistance. But what we learn as we study this period and its unknown actors more closely is how diligently, imaginatively, courageously, and successfully young Jews resisted. As a fine historian concludes in her history of Jews in France during the Second World War: “The proportion of Jews in the Resistance was greater than that for the French population as a whole.… [The underground] remained an alternative society that had taken in Jews on an equal basis and offered them a chance to act without changing any part of their identity.”37

Why had the Manouchian Group rattled the Vichy and German Occupation authorities so much that they worked diligently to paste thousands of copies of the Red Poster in large and small cities across the whole of France, almost overnight? How did a team of about twenty-five persons, most in their twenties, become literal poster children for a defiant resistance to increasingly uneasy Germans? The group was in effect a carefully planned effort by the Communist Party and other leftist resistance groups convinced that there had to be a relentless campaign not only of propaganda but also of organized violence if the Nazi propaganda machine were to be neutralized. The Germans took stark notice.

A Female Resistance

Of those arrested by the Brigades spéciales, we must note and remember that there were dozens of young women. Without the help of women and girls, the Parisian resistance, no matter its ideology, could not have been as successful as it was. We have already noted that Paris had become a city where many, many young and middle-aged men were in prison, concentration camps, in hiding, or in the underground. Women were holding together households, in many of which there were several children, with string and baling wire. They were often outspoken about the deficiencies in the distribution of food and consumer goods, sometimes taking to the streets to voice their concerns, Germans or no Germans. And they were especially active in underground movements:

They despised the Germans, who had sent them on the road during the exodus of June, 1940; who kept their husbands, brothers, and sons in prison camps; who made their daily life so difficult with so many interdictions, shortages of food, of clothing, of coal; with constant ID checks in the street, with hostages shot, and with the roundups of Jews.… Women were indispensable in all domains. It was they who typed and coded messages; there was no word processing in those days, and typists were always women. They served as liaisons between groups and individuals; they were the ones who accompanied a résistant or an Allied pilot on the run, because couples were less often stopped than a man alone. They lodged all these men in hiding, openheartedly, washed their clothes, fed them, and took care of their wounds.… Many went to prison and were tortured. Sometimes it takes more courage to do laundry… than to use a machine gun.38

Hundreds of women took in Jewish children during the most oppressive years, 1942–44. Pretty French girls would flirt with the Occupier while carrying forbidden stencils in their bicycle pumps; they would smile brightly as they passed the French police with tracts, or even munitions, hidden in their prams under their babies’ bodies or under skirts that made them look pregnant.

Girls were often the boldest when confronted directly, as they were in the matter of the imposition of the yellow star. Many of the Gentiles who confronted the Germans with their own stars, making fun of this ukase, were young women. And they were arrested and incarcerated for months. Françoise Siefridt’s recently published memoir, J’ai voulu porter l’étoile jaune (I Wanted to Wear the Yellow Star), reveals the honesty and passion of a nineteen-year-old. On the Sunday morning following the mandated deadline for wearing the bright yellow stars, she and a fellow Christian friend proudly walked down the Boul’ Mich’ (an age-old popular abbreviation for the Boulevard Saint-Michel, which cuts right through the Latin Quarter, on the Left Bank of Paris). She wrote that they were insolently displaying “a magnificent yellow star that we had crafted. I had written on mine PAPOU [from Papua New Guinea]. Passersby said ‘Bravo’ or gave us an approving smile. But a [French] policeman whom we had just passed made a sign to us: ‘What if I took you to the station?’ Another in civilian clothes who was behind us added: ‘Take them to jail’; and, as if he feared that the uniformed officer would let us go: ‘I’ll go with you.’… I followed them without any concern, convinced that after a good talking-to we would be let go.”39

The young women soon found themselves sitting on benches in the precinct’s waiting room, imagining their punishment. A young Jewish girl was brought in with a male African friend who had been insulted by a German.* The girl had insulted the German in return, and she was immediately locked up; the black man was sitting there waiting to see what would happen to him. Françoise’s father immediately appeared at the station; he was allowed to embrace her but not to speak. By his look, though, she knew that she was in more trouble than she had imagined.

Soon the girls were transported in a Black Maria (police van; the French call them paniers à salade: salad baskets) to Tourelles prison, in the northeastern part of Paris, then the official jail where Gentiles who publicly supported Jews were interned. Françoise saw a few other young Gentiles there, too, because they had made fun of the yellow star. Put into cells at first with Jewish girls, Françoise noticed that these latter did not remain long in the cells; they were being separated from their Gentile friends and sent off in convoys to Drancy. On June 20, “the ten Aryans who are in the camp for having worn the yellow star on June 7 are ordered to wear [in prison] the Jewish star, plus an armband inscribed FRIEND OF JEWS.”40

Two weeks later, a German officer appeared in the camp; concluding that their armbands were not big enough, he ordered them enlarged. At the same time that she was being punished for having mocked the Occupation authorities Françoise watched as Jews were being brought in for not having obeyed the yellow star edict, witnessing firsthand what many Parisians were ignoring or refusing to see: namely, that their fellow citizens were being reported, picked up, and imprisoned for ethnic reasons. If Françoise had been a casual “friend of the Jews” before, she was a formal one now.

In prison for two months, Françoise was never told when she would be released; on August 13, she and her Aryan friends were also transported to Drancy. It is unclear why the Germans—or the French—treated French teens this way; after all, they did not want to upset the French bourgeoisie unnecessarily. Perhaps it was just a bureaucratic mistake, but it must have been terrifying, not only for Françoise and her comrades but also for her parents and relatives.