Chapter Seven

The Most Narrowed Lives—The Hunt for Jews

“Maman, qu’est-ce que c’est: juif?” (Mama, what does “Jew” mean?)

—Hélène Elek1

Being Jewish in Paris

How often was the above question asked by Jewish children aware of how anxious, protective, and suspicious their parents had become after June of 1940? At this time, there were about three hundred thousand self-identified Jews in France. About half of them, at least at first, lived in the northern, Occupied Zone, but soon tens of thousands began immigrating to the southern, Unoccupied Zone. European, North African, and Middle Eastern Jews had seen the capital of France as a “new Jerusalem” since 1791, when the Assemblée nationale had given them full civil rights, later confirmed, though with occasional bureaucratic hiccups, by Napoleon I. Beginning with the enormous political upheavals of the mid-nineteenth century across Europe, Jews from eastern Europe, and many from the Ottoman Empire and later Turkey and the Levant, sought France as a refuge. Some came because they tired of the official anti-Semitism, the pogroms, and the lack of economic opportunity in their homelands. Others came because of their progressive political beliefs. Of course, millions had to remain in Poland and Russia, in ancestral shtetls, villages, small towns, and large cities.

By 1939, two-thirds of the Jews in France lived in or around Paris.2 They were not a homogeneous group. Some had become so assimilated that they barely remembered they were Jewish. These generally lived in the western part of Paris, in the 8th, 16th, and 17th arrondissements; if they practiced Judaism at all, it was only on the high holidays. Others were highly observant and tended to settle in the Saint-Paul quarter, a quite poor area of the Marais, just a few blocks from the city hall. Jews all over Europe knew of this neighborhood, called the Pletzl, Yiddish for “little place.” Soon the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th arrondissements were chock-full of small, artisanal businesses, many operating from the owners’ own apartments. Those Jews who were more politically than religiously active—consisting mostly of leftists (but not necessarily Communists), Zionists, and others who were strongly anti-fascist—tended to congregate in the 11th and 20th arrondissements, in the former villages of Belleville and Ménilmontant. Cloth merchants and clothiers set up shop in the northern 18th arrondissement, near the enormous flea market at Clignancourt (which is still there today). The Russian Jews generally chose the 19th arrondissement, near Montmartre. All these districts, with the exception of those in the richer western quarters, were centers of low-rent, decaying, badly serviced buildings, where large families shared small apartments and where each ethnic group could hear the languages that it had brought from home: among them Ukrainian, Russian, Armenian, Polish, Yiddish, Czech, Hungarian, and German. Dozens of newspapers were available in these languages as well. Sixty percent of Jewish immigrants were artisans and craftsmen who worked from their homes and who often had carts that they pushed or pulled throughout the city.

By the late 1930s, Jews knew to keep their heads down, even before the Germans had arrived. “If we keep quiet,” they seemed to intuit, “we may just be ignored.” In November of 1938, a year before the invasion of Poland, a young Polish-German illegal immigrant blew apart the shield of anonymity that French Jews were using to hide under. Angry that Germany had deported his parents back to Poland, where they were put into camps, seventeen-year-old Herschel Grynszpan walked into the elegant German embassy on the Rue de Lille, right behind the Gare d’Orsay, on the Left Bank. Surprisingly, he was not stopped or searched. Entering the building with confidence, he was shown upstairs to talk with one of the three legation secretaries, the young Ernst vom Rath. Vom Rath asked how he could help, at which point Grynszpan pulled from his pocket a small pistol, which he had purchased that day, and fired five times. Grynszpan was immediately grabbed by German diplomats and brought to the street, where he was handed over to the French police without a struggle. In the car on the way to their station, he calmly offered: “I have just shot a man in his office. I do not regret it. I did it to avenge my parents, who are miserable in Germany.”* 3

As vom Rath lay dying in a Paris hospital (he would pass away two days later), Hitler and Goebbels talked about how to react, beyond making the usual diplomatic complaints. Their response was the largest organized pogrom in Germany before the war, what has become known as Kristallnacht (Night of the Crystal, in reference to the sounds and sights of broken glass). Jews throughout Germany were arrested in large numbers; many were beaten and some killed by Gestapo and brownshirt hooligans; signs were displayed on Jewish-owned shops that declared REVENGE FOR THE MURDER OF VOM RATH; thousands of establishments branded as Jewish were looted and vandalized; hundreds of synagogues desecrated; whole neighborhoods ransacked. On November 17, Vom Rath was honored with an elaborate state funeral in Düsseldorf, which Hitler attended. The death of this middling young diplomat had provided the Reich with the excuse to send the strongest possible message to Jews throughout Europe that they would not be safe under German occupation should war break out, which it did only ten months later.

Parisian Jews were appalled that this murder had taken place in the midst of their city. The event brought attention, especially through the right-wing press, to the fact that there was a large Jewish population in Paris, many thousands of whom stateless, all waiting to create confusion and havoc at the slightest provocation. (One of the ironies of the Second World War is that had the Jews of Europe actually had the economic, social, and institutional power imputed to them by raving anti-Semites, they could have easily thwarted their sworn enemies.) Another tension, too, was evident in Paris, and that was the cultural, religious, educational, and even ethnic differences among Jews themselves. When the first ukases began coming down from the Vichy government and the Occupation authorities, many French Jews did not believe that these edicts applied to them. Impatient, even angry, toward their coreligionists, they would gradually discover that, in fact, to the Germans and many anti-Semitic Vichy officials, all Jews were the same.

With the outbreak of war in September of 1939, Germans and Austrians who had fled to Paris were rounded up by French authorities and put into concentration camps. They were sitting ducks when the Nazis took over and began roundups of their own recalcitrant German compatriots—e.g., Communists, Socialists, labor leaders, and Jews.* The Vichy government, before the Germans had unpacked their bags, began to issue edicts aimed at putting Jews in their place. Between July of 1940 (only a month after the Occupation) and October of that year, they passed edicts that repealed naturalizations granted after 1927 (thereby depriving thousands of immigrants of citizenship). They regulated medical professions (a foreshadowing of the delicensing of Jewish doctors), repealed a law against racial defamation, and passed legislation that limited membership in the legal profession.

There was also a law passed in October that defined what a Jew was; another permitted departmental prefects to lock up Jewish immigrants so as to reduce the “excess of workers in the French economy”; yet another removed citizenship from French Jews of Algeria, up to then considered French. In September of 1940, the German authorities (still controlled by the Wehrmacht) published an ordinance defining a Jew as “a person belonging to the Jewish religion or having more than two Jewish grandparents (in other words, who also belonged to the Jewish religion).”4 The Vichy government a few days later published a similar ordinance; for the first time since the Revolution, the French government was officially identifying ethnic groups. Though Vichy took care not to speak of Judaism per se but rather of lineage, the difference was barely noticed by the Jews themselves or, for that matter, by most French people. The German ordinance also instructed that all Jews in the Occupied Zone must report to their local police station and register as Jews before October 20; by October 31 all Jewish stores were to have affixed to their businesses a sign in German and French: JÜDISCHES GESCHÄFT and ENTREPRISE JUIVE (Jewish business). Between October of 1940 and September of 1941, the Vichy government had published twenty-six laws and thirty decrees concerning Jews.5 The drip, drip, drip of these edicts, accompanied by officially approved radio programs and newspaper editorials excoriating the smothering effect of the Jewish race on French culture, religion, and the economy, immediately divided most Jews into two camps: those who tried to leave, and soon, and those (the majority) who had to stay or could not believe that they were personally in danger if they just followed the rules.

It may surprise us today that by the end of October in 1940 about 150,000 Parisians had docilely trooped to Parisian police stations and registered as Jews. (Remember that these were only those residing in the Occupied Zone, for the Vichy politicos had not agreed to the German request that they do the same in the Unoccupied Zone.) But it is understandable if we put ourselves in their shoes: What other options did they have but to follow the laws of their own government and the powerful Occupier? The repression was relentless, and escape was far more complicated than it might seem today. Soon Jews were forbidden to serve in positions where they would have to meet the public (which meant that no Jew could be a concierge); Jewish bank accounts were frozen and lockboxes opened. Apartments were seized, requisitioned, and looted, either by the police or by their neighbors. Writes one historian, “By the summer of 1941, according to [an] estimate made at the time, almost 50 percent of Jews found themselves cut off from all means of earning a living.”6 For every injunction or law or requirement Jews followed, another was introduced.

The propaganda campaign against Jews and Judaism raced toward an apogee of hatred. Taking clues from ten years of anti-Semitic vitriol in Nazi rhetoric, the Vichyists produced their own campaign of misinformation: cartoons, posters, photographs, and newspaper diatribes unencumbered by any sense of decency. Jews who at first thought that France would protect them from the Nazi ideology discovered the opposite. In September of 1941, on every Parisian kiosk appeared huge posters that announced a massive exhibition at the Palais Berlitz, in the city’s 2nd arrondissement: Le Juif et la France (The Jew and France). This exhibition’s raison d’être was to show the French how to recognize the “racial” characteristics of Jews: they had already heard that the Jews were behind Bolshevism, capitalism, and the British Empire, but now they had to know how to discover those who had changed their names (forbidden by edict in February of 1942) and those who were otherwise trying to “pass” as Aryans. Professor Georges Montandon, author of Comment reconnaître le Juif? (How to Recognize the Jew, 1940), curated the exhibition and would be appointed in 1943 the director of the Institute for the Study of Jewish and Ethno-Racial Questions. A hit, the show attracted more than two hundred thousand Parisians (among them, quite probably, were many Jews fascinated with the depiction of their “race” by the Nazis).*

Just a few months earlier, French movie screens had begun showing Veit Harlan’s film Le Juif Süss (The Jew Süss), produced by Goebbels and his propaganda ministry. It depicts a famous Jewish courtier of eighteenth-century Germany as a conniving, manipulative, greedy, and sexually obsessed paragon of his race. More than a million French citizens would view this juggernaut of anti-Semitism by 1944. However, many who went to see it were appalled, and small, unplanned demonstrations, especially among students, occurred throughout France wherever it was shown. Nevertheless, events such as the exhibition and the film continued the deadly drumbeat of anti-Semitism that became part of the weave of French society during the Occupation.

The Jew in France: Vichy Propaganda. (Bundesarchiv)

The level of anxiety rose as families argued about whether to leave for the Unoccupied Zone or the Italian Occupied Zone, known for its more casual attitude about bureaucratic control of Jews. Should they send the children into hiding? Should they find a hiding place in Paris? Whom could they trust? One of the main problems was that these families were often large; not only did they have children to worry about, they also had their fathers and mothers and aunts and uncles, who were not as easily moved. There is one story of a grandfather who took his own life so that his family would not be encumbered and could slip south into the Unoccupied Zone. For a time, the richest Jews could pay their way into Switzerland, Spain, or Portugal (not all had enough foresight to do so). But what about those without comparable resources? Perhaps they could find a cheaper way, such as someone who could get them over the Demarcation Line, in the center of France, between the Occupied and Unoccupied Zones. But the Germans soon closed off that option, too: Jews were not allowed to move, period.

At first, as Jacques Biélinky noted in his journal, German soldiers occasionally protected Jews against their anti-Semitic French neighbors if they were harassed while standing in lines or at soup kitchens. At one point, “in order to prevent attacks against the Jewish population of the 4th arrondissement, patrols of [French] gendarmes began to move about the streets.… This impresses visibly the Jewish population, obviously worried.”7 Yet such events were the exception. Jews soon began to realize that with general restrictions on foodstuffs, fuel, and clothing, it would only be a matter of time before they would be at the end of every line. Still, despite the weekly beat of anti-Semitic edicts and laws, life in the Jewish quarters proceeded quasinormally. But Biélinky noticed that he was hearing more frequently about Jewish suicides, about companies asking employees to sign a statement saying that they were indeed Aryan. At the same time, he noticed a “war of the walls,” in which anti-German graffiti and the defacement of German posters reminded the Jews that they were not alone in their disdain for the Occupier. Biélinky optimistically, and perhaps somewhat naively, noted that, after the November 11, 1940, demonstration on the Champs-Élysées, “the anti-Semitism that had existed in the Latin Quarter before the war has totally disappeared today, and the relations between Jewish and Catholic students (even those on the right) are cordial.”8 Reading between his lines, we see the contradiction: he wanted to be an objective journalist, but he was a fearful Jew, too. He was searching desperately for evidence of an anodyne relationship between Jews and their state enemies. This was a common state of mind for even the worldliest Jews.

Displacement of Jewish residents took place regularly, often without arrests. Claims were put on apartments, especially large, well-furnished ones. The Germans had lists of private libraries, galleries, and art collections owned by Jews. They knew about safe-deposit boxes and items in warehouse storage, and had traced the movement of collections from Paris to private châteaus in the nearby countryside. Large mansions were immediately confiscated. A Rothschild mansion across the street from the Élysée Palace was one of the first.* When a less prominent Jewish home was raided, it most often was sealed and the keys given to the concierge or a neighbor. Later, movers would come to take away everything in that apartment if the neighbor or concierge had not beaten them to it. When arrested, Jews were permitted to carry away almost nothing; even toys were taken from deported children and left behind, an especially cruel act.

Serge Klarsfeld, the indefatigable historian and agitator for the rights of those taken away as well as those left behind, published in 2005 a small collection of letters and memoirs that contains the woeful depiction of what happened when a man who had escaped the roundup returned to find his home empty. “My throat closed like a watertight door; I ran up the streets, looking only straight ahead; I saw no cops or Germans. Arriving in my street, French [i.e., non-Jewish] women stopped me with compassionate faces: ‘Poor man, they took your wife and your son. You, you’re probably a French citizen, that’s why you are still free.’ I said nothing; I could not speak.”9 Other Jewish fathers and husbands, who had thought they could outsmart the French police and their German accomplices by staying away from home, would return to their buildings for belongings or a few clothes only to be told by recalcitrant concierges that the apartments had been sealed or that they were forbidden to let them in. Some, coming back a week later, would see large trucks emblazoned with GIFTS FROM THE FRENCH PEOPLE TO HOME-WRECKED GERMANS parked at the curb; workers were emptying the Jews’ apartments and loading their belongings onto the trucks. What was left soon disappeared into the concierge’s loge or neighbors’ apartments.

The first large roundups began a year after the Occupation, in the spring of 1941. As we observed earlier, Jews in France lived in or near large cities—Paris (with the most Jewish residents, by a large majority), Lyon, Marseille, Bordeaux, and Toulouse. The first significant raid occurred in Paris in May of 1941 (and netted about four thousand Jewish men, mostly Polish immigrants); the second was in August (especially in the 11th arrondissement), and there was another, in December of 1941—this was the first and only time that a raid was led solely by Germans. Most of the raids, as would be the case for the largest one, in July of 1942, would be organized and carried out by the French police, closely monitored by the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives. In fact, members of the French, not the German, police performed more than 90 percent of the arrests of Jews during the Occupation. Those arrested in these raids were boys and men ages sixteen to fifty-five, and for the most part they were foreign-born, unnaturalized. (There was always a handful of French-born Jews in these early roundups, though the Vichy government resisted German demands that they be arrested en masse. As the war proceeded, the distinction between foreign-born and French Jews would slowly evaporate.) In general, the detainees were sent to concentration camps spread all over France, in the Occupied and the Unoccupied Zones. Each of these raids, too, had specific Jewish nationalities as targets, identified according to their home country’s relationship with the Reich. For example, Hungarian Jews were generally ignored until Hitler invaded that country in 1944.

And then, in late March of 1942, the Germans, with the close support of the French police, began putting Jews (and some Communists and underground members) onto trains and shipping them from Bobigny and Drancy to an “unknown” destination in Germany or Poland.* For the next two and a half years, thousands of Jewish women, children, and men would be sent primarily to Auschwitz but also to Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, and Ravensbrück. Until then, Drancy had been a transitional prison camp for those who were to be transported to French camps. Detainees might be released from time to time (after they pulled strings or paid or argued for their liberty); letters and packages could be sent and received, and even visits were permitted. But after the arrival of SS officer Alois Brunner in June of 1943, “a wind of anguish blew into the camp.”*10 A protégé of Adolf Eichmann, Brunner was there to prepare the German appropriation of Drancy, which took place on July 2. Brunner forbade the wearing of sunglasses and beards and the receipt of individual food packages (all such deliveries had to go to the central kitchen). Jews were not to look directly at German soldiers or officers and were to push themselves flat against the wall if they met any in a stairwell. Unpredictable violence against internees was the norm. Prisoners who had relatives still “at large” were forced to write them, begging them to join the prisoners at Drancy—or else.

Drancy fast became known not as a final destination but a temporary transfer station until enough cattle cars could be found to load between eighty and one hundred human beings into a space for eight horses. Last letters were sent from the camp or thrown from the trains as they passed through stations on the way. Many began: “We are on our way to an unknown destination.” It would take months, but soon the word began to come back—from camp escapees, even from some sympathetic German soldiers—that many of the deportees were being gassed right after they arrived at Auschwitz. Disbelief abounded, but soon the immensity of their fellows’ fate did sink in, and though they often refused to talk about it, even among themselves, more Parisian Jews searched for places to hide.

How did news of the camps, and eventually of the death camps, seep into the Jewish community? In the summer of 1941, Jews had been ordered to turn in their radios; as of August of 1942, they were forbidden to have telephone accounts. All newspapers remained under strict German and Vichy censorship, but there were many underground tracts distributed. One that appeared right after the Grande Rafle of July 1942 baldly stated: “We know that 1,100 Dutch JEWS, taken to the concentration camp at Dachau, in Germany, underwent experiments with TOXIC GAS and that almost all died.”11 And the grapevine was strikingly efficient, primarily because many Gentiles, and not a few policemen, helped create it. But who knew what the truth would turn out to be?

Jewish men knew that the police and the Germans were arresting males—rarely women and never children. This demographic selection probably helped to undercut those who had news of death camps in Eastern Europe. Why would the Germans go to all the trouble to round up, imprison, and transport healthy Jewish men just to kill them? They might work them to death, but that could take years, and “years” meant that anything could happen. The Germans cleverly kept the Jewish population off balance, using their roundups to identify certain national groups, e.g., the Czechs or the Poles, and the Jews themselves found a thousand excuses that would permit them to avoid thinking of the worst: “They were recent immigrants.” “They were Communists.” “They were Germans.” “They didn’t have the correct identification.” “They lived in dangerous neighborhoods.” “They didn’t have families.” The excuses served to calm, and many remained, protected at least for a while by luck and their own savvy.12 Lazy or sympathetic policemen, Gentile neighbors who were as alert as they, money to buy off bureaucrats, superbly forged papers, and even certificates that stated that the carrier did not belong to the Jewish race saved many from arrest and deportation.

Three Girls on the Move

Three tales give us an intimate picture of the ways in which young Jewish girls, from three different communities, learned to accommodate themselves to a city under occupation by officials who despised them. In 1988, doing archival research for one of his fictions, the French novelist Patrick Modiano noticed an advertisement that appeared in late 1941 in Paris-Soir, Paris’s most popular newspaper. It read: “Missing: a young girl, Dora Bruder, age fifteen, height 1m 55cm, oval-shaped face, gray-brown eyes, gray sport jacket, maroon pullover, navy blue skirt and hat, brown gym shoes. Address all information to M. and Mme. Bruder, 41 Boulevard Ornano, Paris.”13 There in laconic prose lies a sad tale, which Modiano turns into his documentary fiction, Dora Bruder. A Jewish adolescent had run away from home, and her desperate parents, already lying low, had to go public to find her, thereby drawing attention to their presence in Occupied Paris.

Modiano imagines Paris as it must have appeared to Dora, an unhappy teenager in a city that no longer provided the cocoon of familiarity and that was threatening to her and her family. The familiar Métro lines might have comforted Dora. When all else is mystery or danger, the predictable Métro might offer a sort of mental emollient. The labyrinthine city beckoned this teenager with its promise of experimentation in anonymity. Not even the stark fear of being discovered by an implacable police force daunted young Dora, or raised the idea, had she entertained it, that her parents’ concern could lead them to danger. It does not take much for a youngster to explore, even irresponsibly: “The sudden urge to escape can be prompted by one of those cold, gray days that makes you more than ever aware of your solitude and intensifies your feeling that a trap is about to close.”14 But this freedom is nothing but a seductive lure, and Dora must have at least intuited that she had been “placed in bizarre categories [she] had never heard of and with no relation to who [she] really [was].… If only [she] could understand why.”15 We never learn where she spent the months she went missing, but we are moved by the fact that, possibly, she finally might have met her concerned parents again at Drancy, where they all waited for deportation.

In another memoir of the Occupation, the philosopher Sarah Kofman’s Rue Ordener, Rue Labat (1994), we read of a young girl, as she grows from the age of about eight to ten, who has to deracinate herself, geographically, ethically, and relationally, in order to survive.* When her father, a rabbi, is hauled off to the Vélodrome d’Hiver in the infamous roundup of July 1942, Sarah’s mother has to find a new apartment, at least temporarily, until she can get to the Unoccupied Zone (perhaps because there was a two-year-old at home, she and her six children were not arrested). Fortunately, a Catholic friend who lives only a few blocks away invites her and her children to stay there. Soon, though, other arrangements must be made, and little Sarah is left alone with this woman, who lives on Rue Labat and whom she calls Mémé.

The memoir recounts young Sarah’s move from “Rue Ordinaire,” as she called her former home on Rue Ordener, to “Rue Là-bas,” her name for the home on Rue Labat.* Though only a street or two apart, this distance is psychologically enormous: “One Métro stop separates the Rue Ordener from the Rue Labat. Between the two, Rue Marcadet; it seemed endless to me, and I vomited the whole way.”16 At the cusp of adolescence, Kofman is bewildered, bereft, and frightened, unprepared for the “liberty” that is being forced on her. Immediately, she is thrown into conflict: she comes to love her new “mother” as much or more than her birth mother. She becomes a perfect little Gentile disciple, eating pork and horse meat and breaking Shabbat decorum while listening to Mémé casually reprove the Jews. This sudden, new freedom, at first scary, then exhilarating, soon becomes suffocating, for now she has two mothers, each asking that she choose between identities: a Catholic or a Jew, French or foreign, young woman or child.

The only times that she feels free are when she walks the streets of the 19th arrondissement or takes the Métro. There is scarcely a page of this memoir that does not have a geographical reference—the name of a street, an impasse, a boulevard, a Métro stop, a quartier, a monument. Kofman, remembering a traumatic adolescence, literally “renames” Paris as she tries to buttress, as an adult, her own continuing sense of namelessness, her loss of a stabilizing identity. The names of Paris have not changed; clinging to them helped dilute her unease at having to live in a city under occupation, either by Germans or irrepressible memories.

Hélène Berr, college student. (Mémorial de la Shoah)

In 2008, there appeared on the shelves of French bookstores a book whose title was simple—Journal—and whose cover featured the photograph of a beautiful young girl, the sort of photo that one would give a close friend. The author was Hélène Berr, and through her, we receive yet another new geography of the occupied city. Indeed, her diary entries are so specific about topographical data that one can map easily “her” Paris. There are well over two hundred specific site references in her work—streets, bridges, Métro stations and lines, buildings—which emphasizes how much her sense of freedom depended on her constant comings and goings, marked by familiar names and places. Her diary covers but two years—from the spring of 1942 until the spring of 1944, with a ten-month break—yet it offers its readers a glimpse of how a young person attempted to lead a normal life in an increasingly threatening environment. Hélène was searching, through writing, to transform the threats of occupied Paris into an imagined city, one where she had once been secure and free. It was in the Latin Quarter, among her fellow students, that she felt the safest, even after the imposition of the yellow star. There she intuited that the neighborhood’s intellectual cosmopolitanism could somehow protect her from the tacky provincialism of the Occupation. In the Sorbonne’s amphitheaters, she was just another student. In the courtyards of the Sorbonne, she fell in love. In the library of the English studies department, she answered polite questions of German soldiers. Her friends had conspired to create ersatz “stars” to show their solidarity. She copies verses of Keats to push the Occupation from her thoughts.

Hélène Berr’s home in Paris

Yet she had daily to return home, to an apartment where her father was constantly in danger of being arrested, where the phone rang regularly to inform her mother of another Jewish family caught up in the sticky web of Nazi and Vichy anti-Semitism. The mundane doorbell was no longer a harbinger of pleasant visits; it could announce, heart-stoppingly, the police. “If they ring the bell, what do we do?”17 About a month before the imposition of the “star” in late May of 1942, Hélène came to terms with the knowledge that she was being identified as a pariah.

Saturday, April 11. This evening I’ve a mad desire to throw it all over. I am fed up with not being normal. I am fed up with no longer feeling as free as air, as I did last year. I am fed up with feeling I do not have the right to be as I was. It seems that I have become attached to something invisible and that I cannot move away from it as I wish to, and it makes me hate this thing and deform it.… I am obliged to act a part.… As time passes, the gulf between inside and outside grows ever deeper.18

She is still a Parisian, still a student, still a young woman in love, but she no longer completely belongs to the changed cityscape. After the star edict she notices how people look at her as she walks through the streets wearing her emblem: some are sympathetic and give her a thumbs-up sign of solidarity; others turn away; others look at her in disdain. She is proud; she is resolute; she is still French, but “out of place.” She has been exiled while remaining in her city.

The Occupation authorities tried mightily to restrict movement in the city of Paris—for everyone. Walking freely might have been the only form of resistance available to those living in a tightly controlled city, and Berr walks everywhere. She also takes the Métro, but there she is reminded constantly of the Jewish laws (once “starred,” she is unable to ride anywhere but in the last car) or of the possibility of identity checks at the exits. Berr not only describes where she goes and why, she details how she gets there, as if she is using Ariadne’s thread to keep her connected to her family and to the security of the apartment. The young girl analyzes her affective relations, but she also hints at something more sinister, a time where all Jews will be caught in the web of self-deceit, of deceiving others, and of feeling less free, “attached” by invisible cords to a plan of movement that will limit their physical and psychological liberties.

Berr lived on the Left Bank, close by the Seine, and she often refers to the river as a place of solace and contemplation. Its continuous, inexorable movement toward the sea attracts her. Its bridges give a weak promise of escape from an Occupied land, though she knows that the Germans are “over there” as well as “over here.” The street—Avenue Élisée Reclus—where her family resided is in one of Paris’s most coveted neighborhoods. Named for a French geographer, the name also suggests the safety that many French Jews sought immediately after the Occupation—a “hidden Elysium.” Quiet and shaded, the road runs along the side of the Champ de Mars, almost under the Eiffel Tower. Its neighborhood is about as far away as one could get imaginatively, if not geographically, from the teeming Marais or the 20th arrondissement, where so many foreign and poor Jews lived. When one walks the street today it is hard to believe that such a peaceful place would not have protected a family from the Occupiers.* The Left Bank did seem to be less “Occupied” than the Right, primarily because of the large number of offices of the Occupation bureaucrats in the latter. And, of course, it seemed that way because there was still some security to be found or at least dreamed of in the Latin Quarter: “I walked down Boulevard Saint-Michel beneath the glorious sun among the milling throng, and by the time I got to Rue Soufflot all my usual marvelous joy had returned. From Rue Soufflot to Boulevard Saint-Germain I am in an enchanted land.”19 Berr creates an imaginary map of the Latin Quarter, and as she writes those familiar street names in her diary, she reassures herself that there is some overlap between this imagined view of an unbeaten Paris and the real one, between a “safe” and an “occupied” city, that her “own” map is more real than the actual one. She senses that the heart of the Latin Quarter protects her with its intellectual armature and history, even though Jews had been forbidden to register officially for classes at the Sorbonne since June of 1941. Seeing her friends provided “the only glimmer of peace in the hell in which I live, the only way to hang on to real life, to escape.”20 There, her mind is not Jewish or “occupied” as she sits in class; the Sorbonne is a temporary but ultimately illusory haven of freedom. Berr walks, walks, walks through Paris, as if to imprint her body on the city, ensuring that it remain the same despite the threats that increasingly cloud her life and that of her family. She sits in the Jardin du Luxembourg and the Jardin des Tuileries, soon to be closed to Jews. She runs errands all over Paris, on both Right and Left Banks; she returns almost obsessively to the Sorbonne; she rides the Métro, though she finds it smelly and stuffy.

Her final letter, written from a detention camp on the day she and her family were arrested, is to her sister Denise (who was safe) and says that the event they had feared had finally occurred. It returns to the image of a threatening doorbell:

March 8, 1944, 7:20 p.m. This morning at 7:30, dring! I thought it was a telegram!! You know the rest. Tailor-made arrest. [Papa] was the target, it seems, for having had too many exceptions made for him [he was an important chemical executive] over the last eighteen months. A little trip in a private car to the police station. Remain in the car. And then here, the holding place in the 8th [arrondissement]… The French police were rude this morning. Here, they are nice. We are waiting.21

She warns her sister not to return home until they return. She had given her journal to the family cook, who would keep it for years. Hélène Berr and her mother and father were deported three weeks later from Drancy to Auschwitz, only five months before the Liberation of Paris.

These three stories of courageous, naive, frightened, and resourceful Jewish girls have come down to us by way of chance and sorrowful memory. They reflect the psychological confusion that dominates when one’s surroundings are suddenly, relentlessly made sinister. Each of them imagined a freer, more protective Paris than they found themselves in. Each of the three, though not at the same time, discovered that her imagination, in the end, could not protect her from the pernicious efficiency of a focused hatred.

Low-cost housing: Drancy transit camp. (© Roger-Viollet / The Image Works)

A Gold Star

In May of 1942, the German authorities imposed the wearing of a yellow star (the Magen David—ironically, “the shield of David”) on all Jews over the age of six. As we have seen in Hélène Berr’s account, no emblem “narrowed” lives more than the gold star, the invidious symbol of German racial policy. This imposition was more vividly and poignantly remembered (by Gentiles as well as Jews) than any other regulation during the Occupation, and it continues to be among survivors. Neither Gentile Parisians nor Germans could ignore the garish pieces of cloth affixed to coats, sweaters, and dresses: “For the last eight days, the Jews have had to wear a yellow star, thereby calling public disdain onto their heads,” wrote Jean Guéhenno in 1942.22 Ernst Jünger, our “better” German, noted with asperity:

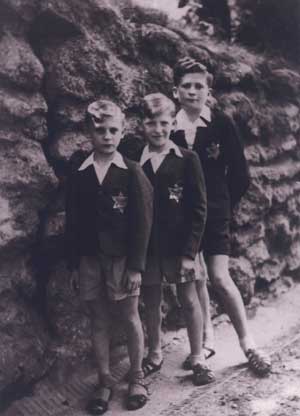

Worn proudly. (Ghetto Fighter’s House Museum)

On the Rue Royale, I came into contact, for the first time in my life, with the yellow star, worn by three girls who passed by me, arm in arm. These markers had been distributed yesterday.… I saw the star much more frequently later that afternoon. I consider that event as deeply affecting.… Such a sight cannot but provoke a reaction, and immediately I was embarrassed to find myself in uniform.23

Of course, having to wear the yellow star gave rise to a devastating realization for the Jews: they were definitely the intended targets of an anti-Semitism that was to be much more vigorous from that point on.

The star was an awkward, if not clumsy, Nazi adaptation of a centuries-old European tradition that was intended to distinguish Christians from Jews in some visible manner. Using the same rationale, starting in Poland in 1939, and then in Germany itself in 1941, the Nazis hoped to use these obnoxious little badges not only to humiliate but also to encourage non-Jews to avoid the despised “other.” The bright yellow badge removed all attempts at anonymity—one of the advantages of living in a large city. Yet the bureaucratic apparatus needed to enforce this law often led to confusion and unintended consequences for both the Occupier and the citizen of Paris.24 Immediately there were exceptions demanded and approved. Would only immigrant Jews wear the star? Or French Jews as well? What about Jewish citizens from other Axis or neutral nations? What if one were only half Jewish, or married to a French Gentile? Why did French Jews have to wear the stars and Turkish and Bulgarian Jews (from countries allied with the Reich) not have to do so? And there were distribution problems. The short span between publication of the law (on May 29) and its implementation (on June 7) meant that a herculean effort had to be mounted in order to produce enough of the badges to be effective. “In France, this meant four hundred thousand yellow stars needing five thousand meters of cloth to be manufactured hastily under orders from the occupier.… For certain messier professions (butchers, those working with children…), stars were specially made in celluloid.”25 We know the names of the French companies that found and prepared the cloth, manufactured the stamps that printed JUIF in bold, quasi-Hebraic lettering, and that produced the stars. One wonders, as artisans employed by these companies worked overtime to prepare these odious markers, what went through their minds.

The order also insisted that: “The badge must be worn about the level of the heart, firmly sewn to the garment, and must always be visible. It is forbidden to hide [cacher] the star in any manner whatsoever. One must take care of the insignias. In sewing the star onto the garment, one must turn under the border that extends past the star.”26 (Stars were delivered in squares and had to be cut or sewn as described; one reason given by the police for the arrest of Hélène Berr’s father was that his star had not been firmly sewn onto his jacket.) The macabre precision of detail, the insistence that the “star of David” be dominant, the assumption that one would easily remove the star under certain circumstances, even the use of the word heart rather than “left side of the chest” and the unintended similarity between cacher (to hide) with kascher (kosher): all this language bespoke the oblivious obsessions that subtended Nazi racial policy.

The Parisian public’s reaction to the yellow star was varied and still fascinates. The injunction had a palpable effect on those who did not wear the star, who looked away when a Jew passed—in the apartment building, on the street, in the shop, in the Métro—thereby making an ethical decision that had been unnecessary up until then. Everything from eye contact to physical intimacies had to be recalibrated. The star created a mobile ghetto, one where Jews were identified publicly for the first time. Overheard were such snide remarks as “Imagine! Such a nice, polite man; when I saw his star I was truly shocked.” Jews (and blacks) had been relegated to the last car on the Métro since 1940, but then there was no way of telling who was and who was not Jewish. Now conductors and ticket takers were instructed to make sure those wearing stars rode in the rear. One Nazi, offended that a Jewish lady confidently wearing her starred sweater had entered the first-class coach of a Métro train, pulled the emergency cord and ordered her out. She was followed by all the Gentiles, leaving the red-faced thug alone in his newly “cleansed” coach.

By then everyone had heard, or had read, of the laws that deprived Jews of property and rights; many Parisians had Jewish acquaintances who had been rounded up, or they had noticed empty and emptied apartments. Yet the overwhelmingly general response had been to half believe Nazi propaganda, which said that those arrested were Communists or foreign terrorists or black marketers. (One of my sources told me exactly this: as a fifteen-year-old boy, he was only interested in girls and bikes; the posters announcing the executions of “terrorists” barely interested him.) Before the star, Jews could “pass” as Aryans (though their official identity papers were stamped with a red JUIF or JUIVE). Now no such shelter remained. For the first few days, groups of young anti-Semitic rowdies would slap Jews in the street or force them inside if they were having coffee on an outdoor terrace. The French police, strangely enough, patrolled the streets to stop this harassment (probably to prevent retaliation), briefly protecting the very Jews who had been humiliated by having to wear the star in the first place. But as noted earlier, there are also many anecdotes about Gentiles saluting, winking at, or otherwise showing solidarity toward Jewish strangers having to wear the yellow badge. During one of her walks, Hélène Berr came across a couple at the Métro stop at the Place de l’Étoile: “There were a young man and woman in the line, and I saw the girl point me out to her companion.… Instinctively I raised my head—in full sunlight—and heard them say: ‘It’s disgusting.’ ”27 The ambiguity of the Gentile girl’s remark emphasizes how daily engagement among citizens had been altered by the appearance of the stars.

Waiting in line with a star. (© Roger Schall / Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet / The Image Works)

The Germans were understandably nervous about the public’s reaction to the gold stars, as memoranda circulated among them indicate; they commented on the complications of the recent introduction of stars in the Netherlands and in Belgium.* Their responses to infractions were swift and draconian, too. The badges worn by some young Gentiles eager to show solidarity, emblazoned with words such as SWING or GOI or INRI, did not amuse the Occupation authorities—or, for that matter, their allies. One woman had put a paper star around the neck of her dog; when stopped by the police, she grabbed it and ate it, according to the police report, but she was arrested anyway. (The Vichy government had forbidden the law’s enactment in the Unoccupied Zone for exactly this reason: fear of public criticism.) Just a few days after the stars began appearing on the streets of Paris, a German police official wrote: “According to intelligence arriving hourly, Gaullist and Communist groups are making propaganda for trouble this coming Sunday [the first since the law’s imposition]. Directives have been given that Parisians sympathetically salute Jews wearing stars on the grands boulevards.”28 The bureaucrat had also heard that many Gentile Parisians were planning to wear their own yellow stars, either blank or with something else written on them, and suggested these individuals should immediately be arrested and put on trains to the east. Perhaps, he mused, Jews should even be forbidden to walk along the Champs-Élysées, the Rue de Rivoli, and other large boulevards the following Sunday. And the chauffeur of a Gestapo official even reported that he had seen Jews appearing proud of their stars, pointing them out with humor and irony to their French compatriots. These latter were saluting them, shaking their hands, expressing regrets. One was overheard saying, “Just wait a bit more. Today they are forcing you to wear the star. But that will not last much longer, and the few Germans who will survive this war will be obliged to wear the swastika for all eternity.”29 Another German wrote indignantly: “Especially surprising was the effrontery with which Jews circulated in groups on the large avenues and paraded in the cafés and restaurants.”30 Some of the more courageous Jews actually sat at tables next to German officers, to the amusement of other patrons. But this would not last long, for on July 15 (just a day before the largest roundup of this period), the Germans published an ordinance that forbade Jews to frequent any public establishment or attend public events, e.g., “restaurants, cafés, cinemas, theaters, concerts, music halls, swimming pools, beaches, museums, libraries, expositions, châteaus, historic monuments, sporting events, racecourses, parks, campgrounds, and even phone booths, fairs, etc.”31

A star in solidarity with Jews. (Préfecture de la Police de Paris)

The star was especially burdensome for children. In fact, Parisians seemed most upset by seeing six-, seven-, and eight-year-olds wearing the huge badges (everyone over six years old had to wear one; there were no children’s sizes) pinned and sewn to their school clothes. Annette Muller remembered how it was. Her mother sewed the stars on her four children’s garments and then marched them down the streets of the 20th arrondissement, ordering them to walk with heads high. “Her arrogant gaze seemed to defy those who looked at us silently,” Annette recalled. “She wanted to show to everyone that she was a young Jewish mother, proud of her Jewish children.”* 32

Closed to Jewish children. (Mémorial de la Shoah)

But what was worse than being paraded by offended parents was having to go to school. We all know that children, after a certain age, want to fit in, not to stand out, so it is not hard to imagine what happened when a child appeared in class (especially in a class with few Jewish children) wearing a huge yellow star. The Gentile parents of many children had not prepared them for seeing their Jewish friends so distinguished, and their first reactions were often humorous, teasing, and occasionally bullying. At school, Muller noticed that her non-Jewish friends stopped asking her for playdates; more significantly, she remembered a very pretty, blond, blue-eyed girl from a very well-off family, a young icon for all the other kids, who showed up the same day with a bright star on her chest. Even Annette was surprised. This was not the only eyebrow-raising event: many folks were surprised to see so many stars on people who did not “look Jewish.” Noted Biélinky:

Even the children. (Mémorial de la Shoah)

Thanks to the stars, [an objective observer] could see that the large majority of Parisian Jews did not carry the classically assumed characteristics of the “race.” Without the stars one could never take for Jews this multitude of young men and women with agreeable, normal characteristics, similar to those the indigenous French population itself would like to have.33

The caricatures that the Germans had been promulgating for more than two years, that Jews were all quasi-Semitic, with pendulous lips, large hands, hooked noses, frizzy hair, and small, greedy eyes, were seen as just that: exaggerations.

Despite this upending of stereotypes, her mother’s courage, and her pride in being Jewish, Annette Muller concluded at that young age that “to be Jewish meant to be dirty, disgraceful, shameful. That shame—I felt it in the street when people turned away at the sight of the star, which marked us like a hateful and stinking stain. Was this what it meant to be Jewish? That’s what I was, and I was ashamed. I wanted so much to be like the others, good people, clean and proper.”34 The attention that the new edicts were increasingly directing toward children also made Jewish youngsters feel uncomfortably “special.” Parks were closed to them; fairs, festivals, puppet theaters, sailing ponds, athletic teams similarly denied them. They had to stay close to home, and be there after 6:00 p.m.

Another French Jew, seventy-year-old Edgar Sée, left us a much more oblique memoir—only recently published, a short notebook of the last year of his life in Paris—which helps us understand why so many star-wearing Jews did not leave the city and even managed to survive, though not he. Sée was an eminent attorney, teacher of law, and active member of his Jewish community. His family had deep roots in the Alsatian community and had been French for at least two centuries. In his diary, he describes a day just after the imposition of the star when he met an elderly Gentile couple on a walk along the Seine: “[They] questioned me about the star, assuring me of their respect and sympathy, just as had previously numerous ecclesiastics, individuals, [and] working-class people especially; [some] would get up to give me their seat in the Métro, or allow me to advance in line because of the restrictions put on our shopping times, etc.”35 He was arrested along with other Jews on his street, the elegant Avenue Victor-Hugo, in a roundup occasioned by the assassination of a German official in his neighborhood. The detained were promptly sent to Drancy. Sée had thought he might be safe from such scrutiny, for he had a friend in the German embassy with whom he had worked for more than ten years when he was younger, but even though that colleague wrote a letter the day after his arrest (“Although he is a Jew, and seventy years old, for years [he] has defended German interests [and] merits the protection of Germany”36), it was ignored by higher-ups, and Sée was deported two weeks later. He did not return.

Sée was caught up in the self-deception of many French Jews, especially wealthy and well-connected ones, such as Hélène Berr’s father, that somehow they could ride out the disaster that was surrounding them, encroaching daily on their lives. If they gave up their arms and radios, if they renewed their IDs, if they wore punctiliously the yellow star, if they rode the last car of the Métro train, they would be fine. “[These French Jews] could not bring themselves to believe that the same men would commit in France the same infamies [they were carrying out in the east]. The country of the rights of man had its traditions and would preserve them.”37

In his unpublished manuscript, the late Berkeley historian Gerard Caspary, a Jewish survivor, annotated an extensive correspondence between his mother, Sophie, and her mother, Martha, who had been living in Sweden since the early 1930s. The letters were written in the early 1940s, as the Germans focused their attention on the Jews of Paris, and he wrote in his introduction that there was a distinct disconnection between what was happening to Jews in the city and in France and the daily lives of the Casparys in Sèvres, just beyond the limits of the capital. On the one hand, mother and daughter, now separated from each other not only by distance but by war, were writing as if the separation were only temporary and could be resolved by either emigration or good luck. On the other hand, the letters speak of the daily problems of living in an occupied environment; but slowly the persecution of Jews, especially the limitations placed on their daily lives, seeps into the correspondence.* Knowledge of what was going on around them gives an aura of solemnity to even the most mundane observations. There is much discussion about cost of living, money transfers, clothing for a fast-growing teenager, cold, and foodstuffs. His mother is proud that Gerard can take the Métro to Paris to go to movies or to accompany his classmates on field trips. Little by little, though, coded terms begin to appear in the letters between mother and daughter that signal deportations, plans for escape, and war news. The yellow star legislation receives only an oblique mention, yet it is obvious that every trip far from their abode, especially into Paris, was fraught with danger. Parisian friends were disappearing, and roundup news was passing fast through the innumerable grapevines that connected Jewish households. Caspary wrote of a “mad sort of normality,” a description of Jews’ efforts to avoid trouble and act as if everything were fine. It remains impossible to know whether Sophie’s letters were written this way because of censors who were reading them, or because she was making a doomed effort to find normality in an upturned world.

Caspary had been born in Frankfurt and came to France with his parents around the age of four. He kept his Jewish origins to himself and only told a French friend or two about his ethnic heritage. He was surprised one day when his teacher told him that he had come in first in a competition but was going to be awarded second prize because he was Jewish. It was the first time the outside world had made a point of his Jewishness. Then came the day when he had to wear the yellow star to class for the first time. His mother told him to be proud, to hold his head up; but he wanted to do that for her sake, not because he was proud: “I was absolutely terrified. Previously I had told only one boy in school that I was a Jew.… When I knew that the Jewish star was coming I told no one of my fears except Claude [his friend], who swore that though all the other kids would turn against me he would stick with me… no matter what.” To his surprise, the school principal had announced to all his students that anyone bullying or otherwise making fun of a Jewish boy would never receive a recommendation from him; in fact, he would be sure that others would not write recommendations for them, either. This did not really mollify poor Caspary. Unbeknownst to him, his mother, “hating and fearing authority figures as much as she did, but knowing how scared I was, must, on her own and without telling me… have gone to the principal and asked him to do something.”*

Caspary described the arrest of his parents by French police succinctly, but quite effectively:

Very early in the morning of October 23 [1943] they finally came for us. We had of course been expecting them since summer. What I remember is that in the middle of the night I came up like a diver out of a very deep sleep with my mother bending over me with one hand over my mouth and the other pointing toward the window, from which there came the shrill sound of the bell ringing, ringing, and ringing. It was pitch dark.… What I remember… is the constant sound of the bell that just went on and on. (They must have inserted a matchstick into the mechanism.)… I started arguing with my father [about escaping out the back door, but he] objected and said that they probably had posted some people in the back. My mother took my father’s side. Finally at 8:00 a.m. precisely (they later told us that they were legally not allowed to break in before that time, something that today I do not believe…), we heard them break down the front door.

Caspary thinks that the police might have been giving his parents a warning, but he never found out, and they were taken like squirrels in a trap. The police offered to let the teenager go (he was only fourteen) if his parents could find a place for him. Sophie called a friend; Caspary embraced his parents and left the house in tears, on his way to a new, safer, and lonelier life. He never saw them again.

The Big Roundup

The French finally remember: Vichy police arrested Jewish children.

Just six weeks after Jews had been ordered to wear the yellow star came the Grande Rafle. Over two days and in dozens of Parisian neighborhoods, thirteen thousand foreign and French Jews were taken from their homes, from their hiding places, from hospitals, from schools, retirement homes, even asylums. As a result of this enormous dragnet, more Jews with French citizenship were caught than ever before. Finally, and most poignantly, more than four thousand children, ranging in age from about two to fourteen, were collected and deported. Many children were abducted from their classrooms, from their kindergartens, and from their nurseries before the eyes of their classmates and teachers. A casual walk through the Marais and other sections of Paris today will reveal plaques that commemorate those events and the numbers involved. Some children were not taken, but when they returned home they found their parents gone and the apartment doors sealed. Or they found the seals broken because neighbors and the concierge had broken in to take possession of objects or the space itself. One police record reports a Gentile neighbor asking, on behalf of a Jewish girl, if she could go into her parents’ apartment to collect a change of clothes.38

Some mothers had left their babies in their cribs, unnoticed by the police because they were not on any list; some had hidden them in closets or in hideaways prepared months in advance. One father kept repeating to his friends: “My ten-month-old is all alone; I didn’t have time to give a key to the concierge, and I don’t know where my wife is!” Sympathetic Gentiles had, fortunately, carried off a few youngsters before the Grande Rafle; and many had been grabbed out of lines, ready to mount buses for Drancy and the Vélodrome d’Hiver. But many more were roaming around a dreadfully quiet neighborhood after the buses had taken away their parents. The neighbors they knew had been carried away, too; most of the children did not know the area around their quarter well at all, for their parents had forbidden them to leave the street or block. They had no money, though we do know that some prescient parents had sewn francs into the hems of their clothing just in case. Fortunately, they did have one organized group of saviors: the Éclaireurs israélites de France, the Jewish scouting organization, similar to the Boy Scouts in Great Britain and the United States. (There were female members, too, and later the name of the organization was changed to include “Éclaireuses.”) These teenagers, who themselves had escaped arrest because they had been living in other areas, were well organized, and their leaders sent them out immediately on July 17 to search the streets for wandering children. They found hundreds of them and took them first to temporary orphanages in Paris, then later, when they could, to the countryside. In this way, thousands of youngsters were saved and survived the war, generally in hiding. Occasionally, groups of children would be denounced by anti-Semitic French citizens and deported, but overall the French people can look with pride at their active participation in being among the “Justes” and in saving these young Jews.*

Nevertheless, the toll was horrific, as was the complicity. The pressure on the Vichy government from the Germans, who felt that the Parisian police and the Vichy masters were dragging their feet on arresting and deporting all Jews living in France, had been enormous. They knew, too, that the Italians were not as fanatic as they were, and that as a result many Jews were living in relative safety both in the Unoccupied Zone and in the zone controlled by the Italians in the far southeastern part of the country. This situation especially offended the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives, that their allies were protecting so many Jews.

Wishing to palliate the German Reich, with which he was still hoping to establish some sort of alliance, the ever canny Pierre Laval, who had returned to head the Vichy government in April of that year, knew that he had to win over (and outmaneuver) a hesitant Pétain, assuring the old Maréchal that only foreign Jews would be rounded up in this massive action. Pétain, it appears, was concerned that his own integrity would be besmirched should word spread (which it did) that the French government was in effect doing the Nazis’ bidding regarding deportation. It is unclear who decided that “families should not be separated,” a decision that would permit the roundup of children with their parents. The blame most often goes to Laval; Pétain always denied knowledge of this decision. We do know that it was not originally a German priority; why would they want to be responsible for the imprisonment and transport of thousands of children? They had even suggested that churches and Jewish orphanages take care of the young ones. But an offhand suggestion by Laval was finally sent to Berlin, and the word came back to the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives that children “could” join their arrested parents. The children were sent to Auschwitz a few months after their parents, a story that spread like wildfire throughout France, and was the death knell that rang out for a corrupt regime.

The French police were deadly efficient. There had been warnings that a massive roundup was about to take place. The Jewish Communists were especially attuned to the plan to make a major sweep across Paris; most likely this information was garnered from their own spies among the Parisian police. A few days before the roundup, a tract appeared in Jewish neighborhoods:

Do not wait for these bandits in your home. Take all necessary measures to hide, and hide first of all your children with aid of sympathetic French people.… If you fall into the hands of these bandits, resist in any way you can. Barricade the doors, call for help, fight the police. You have nothing to lose. You can only save your life. Seek to flee at every moment. We will not allow ourselves to be exterminated.39

And yet.

The collection of files (fichiers) gathered over the previous two years by the Occupiers and their Vichy functionaries provided names, addresses, occupations, ages, and numbers of family members, from which smaller lists were made and handed to each arresting group so that not one registered Jew would be missed. Though the French police have spent years trying to dodge their reputation as enablers, there is no doubt, now that the archives are almost all freely open, that the French forces of order were active, not reluctant, collaborators with the Germans. Indeed, there is no way the Germans could have succeeded as well as they did in rounding up these “illegals” if it had not been for the help of the local police forces. The Germans quite simply did not have enough personnel to track and keep files on Jews or plan and carry out raids, arrests, and incarcerations. Nor did they know as intimately the labyrinth that was the city of Paris.

The effect of this massive roundup was devastating. It ended for once and all the myth that some Jews were protected from the arm of the law. It established without any doubt that the French police were a major, unsympathetic force. There exists no record of even a single French policeman having refused to participate in his assignment. However, quiet subterfuges did occur, and many Jews did escape under the turned gaze of a sympathetic officer, but much of that information is primarily anecdotal, just as is the information concerning the courage of some concierges and the jealous hatefulness of others.*

Filed lives.

About 4,500 French policemen organized and participated in the operation. The Germans were nowhere to be seen—this of course particularly infuriated both the Jews and their Gentile neighbors. Despite the initial successes of the roundup, which began at 3:00 a.m., the German authorities, surreptitiously evaluating the results, were apoplectic. Hoping to round up 27,500 Jews, the great majority of them during the early hours of July 16, the police had only, by midmorning, been able to find about 13,000, and the action was threatening to take a day or more. What was the problem? A note from a French police bureaucrat, written at 8:00 a.m. on July 16, cites excuses for the roundup’s slowness:

The operation against the Jews has been going on since 4:00 this morning. It has been slowed up by many special cases: many men left their homes yesterday. Women remain with a very young child or several children; others refuse to open their doors; we have to call a locksmith. In the 20th and the 11th [arrondissements] there are several thousand Jews; the operation is slow. [Nevertheless] by 7:30, ten buses have arrived at the Vél d’Hiv.40

This roundup collected primarily women and children. The police had reserved about fifty public buses for transport. In retrospect, it was clear that seeing police officers in recognizable uniforms, as well as the familiar green-and-cream buses, helped to calm the hunted. Men composed only about 30 percent of the detainees, for they had by now learned to sleep away from home at night or to hide out; no one thought that women and children were in danger. Most of those rounded up were taken either to the Vélodrome d’Hiver, in the 15th arrondissement, or to the railhead at Drancy. The Vélodrome d’Hiver (Winter Bicycle Track) was a huge covered meeting hall and racing venue. Over 17,000 spectators could watch a variety of events: rallies, boxing, even a bullfight, and the track could be used for roller-skating, even ice-skating. Everyone knew where the Vél d’Hiv was—right near the Eiffel Tower, on the Left Bank. It was a place for screaming throngs of fans, entertainment, and healthy competition. But it would become synonymous with the cruelty of Paris’s acquiescence to the German desire to rid the city of all Jews. Finally torn down in 1959 (after having been used as a holding center for anitcolonialist Algerians in 1958), there is now a Place des Martyrs Juifs du Vélodrome d’Hiver in memory of those incarcerated there for a week during the hot month of July in 1942.

Buses that brought Jews to the Vél d’Hiv. (© BHVP / Roger-Viollet / The Image Works)

Vélodrome d’Hiver at a happier time. (© Roger-Viollet / The Image Works)

The descriptions of conditions in this huge bicycling-rink-cum-concentration-camp were later recounted on film, in memoirs, and in firsthand accounts (several dozen victims were able to escape during the commotion of trying to direct eight thousand people into the building). One example from an eyewitness:

It was like hell, like something that takes you by the throat and keeps you from crying out. I will try to describe this spectacle, but multiply by a thousand what you imagine, and then you will only have part of the truth. On entering, your breath is cut by the stinking air, and you find before you an arena black with people crowded next to each other, clasping small packages [of clothes, belongings, food]. The scarce toilets are blocked. No one can fix them. Each is obliged to do his or her business along the walls, in public. On the ground floor are the ill, with full waste containers next to them, for there aren’t enough people to empty them. And no water.…41

Hundreds of rapidly scribbled and notes and letters from detainees were sneaked out of the Vélodrome, but only about two dozen of them have made their way to the archives of the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris.* They ask friends, relatives, concierges to send them packages; they have no idea how long they will be in the arena or where they will be taken afterward. One Polish woman even thinks she will be released because her two daughters had been born in France, and she asks her concierge if they can stay with her when they return. The letters provide confirmation of what archival research has shown since: there were no uniformed German soldiers at the Vél d’Hiv, only French police; there were thousands of babies and very young children; most of the detained thought they would be sent to French concentration camps permanently; others thought they might be released because they were mothers of small children; some few—e.g., furriers and leather workers—were released because the Germans needed their services (for Eastern Front uniforms).

Among the thousands waiting in the Vél d’Hiv to find out their fate, some committed suicide—these were Jews who knew that the roundup was not just for the purpose of taking names. Perhaps the most moving testimony of this awful week in this awful place comes from a fireman, part of a cohort brought in to check—unbelievably—for fire hazards caused by overcrowding. In 2007, one of those Parisian firemen, F. Baudvin, recounted his story for the archives of the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris. One can still feel his distress sixty-five years later. On entering the forecourt of the arena, he noticed that there were no Germans, only gendarmes and municipal police, but on one side, he glimpsed a few men in civilian clothes—“gabardine,” he wrote. Were they the Gestapo? He did not know or have the leisure to further consider the possibility. As soon as he and his fellow firemen went inside, detainees ran up to them, begging for help, stuffing their potential saviors’ pockets with notes and letters for the outside while pleading for something to drink. Against orders from the police, the firemen turned on the hoses, mercifully spraying the arena and the crowd. They tried to separate themselves from the anxious detainees, afraid that they would be searched, or worse, by the police or the “gabardines” when they left. When they finally returned to their caserne, their chief gathered the five young men:

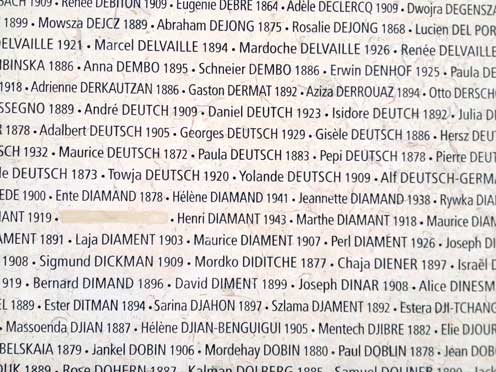

Some were so young. (Names inscribed at the Shoah Memorial.)

You agreed to do some favors during your recent assignment. You must honor them. What you collected should be sent to their addressees, but you should use only the most public mailboxes. Avoid the 7th, 15th, and 16th arrondissements [the wealthiest, where many Germans lived or worked], and be careful. I’m giving each of you liberty for a day; the desk sergeant will give you the permissions as well as some Métro tickets when you leave. Finally, if one of you has a problem, say that you are acting on your own. You received no order or suggestion from me. I won’t be able to help you; leave and do your best.42

Baudvin tells us that he had collected 144 notes and letters. He spent the morning finding envelopes and stamps and trying to decipher addresses before he and his colleagues spread out across Paris to mail what was, for many, the last word received from their imprisoned relatives or friends.*

Next to the assignment of the yellow star, the decision to arrest children between the ages of two and sixteen, then separate them from their parents, was probably the most significant public relations mistake of the Vichy government and their German partners. It is impossible in such a compact city to arrest and move around more than thirteen thousand people, especially when most are women and children, without that information becoming known. The sight of youngsters in buses, roaming the streets alone, or holding their mothers’ hands as they mounted police vehicles made an impression on Gentile Parisians. Police reports following the roundup were especially sensitive to public opinion. Excerpts from two such reports reveal this concern:

The measures taken against the Israélites have rather profoundly troubled public opinion. Though the French population is generally anti-Semitic, it nonetheless judges these specific measures as inhumane.… It is the separation of children from their parents that most affects the French population and that provokes… strong criticism of the government and of the occupying authority.

The arrests of foreign Jews on July 16 and 17 have occasioned numerous reactions among the public. The great majority believed that the operations were aimed at French as well as foreign Jews. In general, our measures would have been well received if they had only been aimed at foreign adults, but many were moved at the fate of the children; rumors are still circulating that they were separated from their parents.43

The French, much more than the Germans, realized that support for the État français depended on the continuing credibility of the Vichy leaders, especially Maréchal Pétain. Already, food shortages, the snail-slow release of French prisoners of war, and declining living conditions had made criticism of Pétain’s “contract with the devil” come under much more incisive criticism from the public. Indeed, the plight of French prisoners was one of the recurring obsessions of Pétain’s government, and the Germans played bait-and-switch games with them for four years. The Vichy administration put a huge emphasis on Famille, Travail, Patrie, but you cannot have a famille without a père, at least according to the government’s own (conservative Catholic) dogma. Thousands of letters written to prison camps from desperate wives must have lowered the already basement-level morale of the French men in the stalags in eastern France and in Germany. And the Vichy government found itself awkwardly caught between the demands of a “new order” based on traditional ideas of family and a recalcitrant German authority that was using the prisoners as a token for blackmail. Once the Unoccupied Zone had been invaded and militarily occupied by the Germans in November of 1942 (the invasion of North Africa by the Allies had convinced them they should protect more closely their Mediterranean flank), Parisians and other French citizens came to see the embarrassing ineffectiveness and political impotence of the État français. Beginning in early 1943, many supporters of Pétain and Vichy would begin to hedge their bets, quietly joining or supporting the Resistance, which was finally coalescing around de Gaulle by this time.*

If we define a city in part by its institutions and its history, Paris will never be able to erase its responsibility for the roundups, especially the “big” one. These events revealed clearly the truth behind the German and Vichy French policy toward the Jews, and they did more to undermine the Occupation’s goals—those of the Wehrmacht, the SS, the Gestapo, the foreign service, and the propaganda machine—than any others. That is one reason why the German reaction to the breakup of the Manouchian Group in late 1943 was so furious: the Germans wanted to prove that France was in more danger from all these foreigners than from them.

In his most famous speech, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Grande Rafle, President Jacques Chirac was the first French head of state to assume responsibility on behalf of all the French and of the republic itself for what had happened; “Oui, la folie criminelle de l’occupant a été secondée par des Français, par l’État français” (Yes, criminal madness was assisted by the French people and by the French state”). It had taken fifty years for such a direct acknowledgment of guilt to have been formally offered, but this, of course, did not put to rest the major questions that continue to harass the French consciousness. How much had a deeply anti-Semitic vein, dating back to the Middle Ages, enabled the Vichy government in their efforts, not to mention the efforts of the Germans? Many French Gentiles put their livelihoods, families, and lives in danger to help their Jewish compatriots and Jewish immigrants, but how widespread was this phenomenon? Why did not more complain to their religious leaders or the government about what they could no longer avoid seeing as the deportations begun in early 1942 and after children were separated from their parents? What could they have done? Why were more than a million letters written to authorities in the five years of the Occupation denouncing neighbors, especially Jewish neighbors? What options did the French police have to resist German authority? When the French saw the first edicts targeting Jews, why was there not more of an uproar? Was it because the French Gentiles, too, had been traumatized by the defeat and the sudden appearance of German soldiers at their thresholds? Did they have their own concerns that prevented an active countervoice? Their new living conditions, and the pressures they were under, forced the occupied to be selfishly preoccupied. Eyes were cast downward, and not toward others too far from their circle. “Why not leave it to the Communists and others to handle this? I have enough on my plate.” “The Allies will probably win.” “You can’t trust everything you hear.”*

These questions can never find complete answers, but in a way that is not something to regret. Pierre Laborie, in his little essays on what certain terms and concepts meant in 1939–40, warns us against being anachronistic, that is, in thinking that we, today, can understand what it was like to live in an occupied city in the 1940s. He warns, too, against thinking that just because it was “only” seventy years ago when all this happened, temporal proximity allows us to assume knowledge of such a different time, culture, and spirit.44 Yet asking these questions is what any society must do once it slips from the path it has set as its purest way. Many French—politicians, bureaucrats, historians—tried for a quarter of a century after the war to erase the memory of Vichy collusion in the Occupation; they failed, and in the almost half century since then they have addressed, straight on, their failures and their successes, trenchantly, effectively, and apologetically. A sense of historical, collective guilt can be seen as the sign of a healthy society, one that does not turn from self-criticism.