Chapter Nine

Liberation—A Whodunit

Paris is like a beautiful woman; when she slaps you, you don’t slap her back.

—General Dietrich von Choltitz, a few days before he surrendered the city

Is Paris Worth a Detour?

In his memoir, Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul in Paris who played a capital role in formulating the surrender of the city by the Germans in late August of 1944, wrote about the news of the disembarkation in Normandy: “Paris was still relatively far from the new front, and life went on as before, but there were many signs of an increasing nervousness. Troop transports toward the west [the Normandy front] grew day by day, while in the circles of German leaders [of the Occupation authorities], great efforts were made to remain optimistic.”1 A former Parisian remembered that, as a young girl, she used to watch these trucks from her windows and hear their sonorous rumbling as they passed her on the way to school. Other witnesses wrote of the changed atmosphere following the unbelievable news of June 6: fast-moving transports and tanks were passing through and around Paris as the Wehrmacht, under the manic control of a deeply paranoid Adolf Hitler, tried with some early success to push the Allied forces back into the English Channel. Beginning in late June and early July, however, signs of the enormous cost to the Reich of the D-day invasion became more visible. (Hundreds of thousands of German troops would die in the three months between the invasion and the collapse of the Wehrmacht in France in late 1944.) Ambulances, trucks, tanks, even staff cars filled with wounded, frightened soldiers, were increasingly seen heading eastward toward the Rhine; camouflaged panzer units were retreating. One French wag covered his rickshaw-like vélo-taxi with dead branches as he rode around Paris, mocking the German attempts at evading Allied bombers.

For purely military reasons, the Germans were desperate to keep Paris in their hands. “From a strategic perspective, the transportation network of Paris and its suburbs was the single most important military asset of the capital.”2 The symbolic reasons that had earlier dominated so much of their policy were much less important now. All French railroads and major highways passed through Paris; geographically, the city also provided a generous redoubt to allow the Wehrmacht to “regroup,” because Hitler had forbidden his armies to retreat. They also hoped that keeping Paris would give their armies retreating from Normandy time to reach Germany before being surrounded. Festung Paris (Fortress Paris) was the keystone in what was left of the German Occupation of France, for on August 15, the Allies had invaded the nation from the Mediterranean and were rushing northward to cut off the Germans trying either to reinforce the Atlantic Wall in Normandy or move eastward to the Rhine. Yet to defend and hold Paris would have taken, as the French themselves had estimated in 1940, at least three corps (anywhere between sixty thousand and 135,000 first-line troops). And where was the General von Gross Paris to get those numbers and the materiel necessary to support them? On top of this, they still had to feed the Parisian population, if for no other reason than to prevent uprisings.

The Germans did have one advantage, though it was unknown to them at that moment. Allied generals Dwight Eisenhower and Omar Bradley did not regard “Paris itself [either] as a major Allied objective [or] a German strongpoint.”3 In fact, Ike would not decide to march into Paris until August 22, three days after the Parisians themselves had begun their insurrection. Given the significance that the city had had for Germany’s propagandistic aims just four years earlier, and given the amount of attention the major branches of the Reich’s government had lavished on the French capital, it might come as a surprise that the Allies did not consider its liberation strategically crucial. This conundrum—if we set aside the military reasons for such a hesitancy—brings us back to Albert Camus’s description of how deeply the inhabitants of an occupied city feel about being abandoned, or forgotten, or overlooked. The hole such anxiety leaves in a population’s psyche takes much time to fill, especially after the hardships endured seem to call for some sort of closure.

Was Paris worth less to the Allies than it was to the Germans? For one military commander, at least, it remained symbolic: soon after the Allies broke through the Wehrmacht’s defensive front in Normandy, Adolf Hitler began plotting to use the city as a means of slowing the enemy’s advances. At first his attention turned to the region’s railway depots, major highways, airports, and the Seine bridges, which he was planning to disable well before the Allies reached Paris. But soon his instructions took on a more hysterical tone: to some of his subordinates, he appeared to want to raze the City of Light, to make it permanently dark. His obsession with Paris was fueled by the fact that he did not trust his commanders in the west (i.e., the Normandy front). Many of the German senior staff in Paris and nearby had been implicated in the assassination plot of July 20, and he was suspicious that his orders were only being dilatorily carried out.* In part, he was right. A German historian remarks that

the commanders in charge in the west occasionally found themselves forced to adapt a rather odd rhetoric to conceal the disparity [between such orders and what was militarily justifiable at any given point]. These commanders formally complied with the contents of such orders, but in the final analysis they executed only those elements that seemed absolutely necessary.4

Paris had become a military conundrum for both sides.

We have seen how tired of living close together both the Occupier and Parisians had become by the summer of 1944. Hope for liberation became almost palpable in the streets of the capital. Yet on the other hand, there was the concern that Paris, like Stalingrad and Warsaw, would become a battleground and that perhaps it would be best for the Allies to skirt the city, isolating a weakened German garrison as they pushed on toward the Rhine and an end to the war.

From the first discussions of an invasion of France, de Gaulle had had the liberation of his nation’s capital at the forefront of his strategy. Did the persistent resistance from both the Americans (Roosevelt never trusted the French general’s political ambitions) and the British (Churchill referred to de Gaulle as his “Cross of Lorraine to bear”) reveal a lack of understanding of what Paris meant to the French psyche? This would have been a strange notion, given the fascination that both nations had for France and her capital. But de Gaulle, along with his supporters as well as those French who were still ambivalent about him, seemed to have best grasped that without Paris, no French government would have the credibility needed to salve the nation’s wounds.* De Gaulle never caved on his demand that Paris be liberated as soon as possible and, at least in part, that it be liberated by French troops.

His problem was that he did not command the French troops necessary to do the job, nor were there enough of them. He had to rely on the Allies, on General Eisenhower and General Bradley, for materiel, support, and men. And, as we have noted, the Allies, taking signals from their forceful leaders, Roosevelt and Churchill, were not overly impressed with the leader of the Free French. They had not even told de Gaulle the date of the Normandy invasion until a few hours before dawn on June 6; they tried to stop him from flying to France on June 14, when he received a rapturous welcome from the citizens of Bayeux, the first major French town liberated. And they made every effort to hamper communications between him and General Philippe Leclerc, the commander of the Second Armored Division, the best equipped Free French unit in the Allied army. At the same time, de Gaulle was worried about the strength of the Communist Party’s resistance movement and about the independence of the FFI, the Forces françaises de l’intérieur, who were acting only partially in concert with him and the Free French stationed in Algiers. He thought it quite possible that the internal resistance movements might assert a moral right to an equal status with the Gaullist initiative or, worse, that the well-organized and well-armed French Communist Party could effect a coup d’état, as the left had in 1871, when Paris refused to accept the French surrender to the Prussians.

Unlike his most impulsive commanders, the British Bernard Montgomery and the American George Patton, Eisenhower believed that a massive push toward the Rhine and then Berlin would be much more effective than the strictly targeted strikes both men preferred. Ike knew that coming behind the establishment of beachheads in Normandy would be enormous loads of materiel and hundreds of thousands of troops. He wanted to beat the Wehrmacht into the ground; a feint to take over a huge city, with all the logistical demands that would ensue, was not practical. If there were a massive uprising, Ike feared he might have to deploy thousands of men to protect a severely underarmed civilian populace. Add to this the fact that President Roosevelt did not want de Gaulle installed in Paris before an interim American occupation authority could be set up and Ike’s belief that liberating Paris in August had to be avoided took on more weight.

As it turned out, in terms of strategy, Ike was right, but de Gaulle outmaneuvered him, as de Gaulle himself had been outmaneuvered by important elements of the consolidated Resistance army he had established earlier. The French leader’s postwar plan for governing the country relied on the premise that the Parisians, with assistance from his Free France government, must liberate their capital. But as we have learned, de Gaulle, too, was concerned that political and ideological parties other than his provisional government might attempt to establish a new French state, or at least demand a large voice in France’s future. A civilian-led insurrection, acting in isolation of Allied plans, would threaten his leadership. To de Gaulle’s chagrin, Colonel Rol (whose real name was Henri Tanguy), leader of the Resistance in Paris and an important Communist partisan, had threatened to order such an uprising (which he would do later in the month) to force the Germans to leave the city. On the other hand, the Germans were desperate to keep the city’s massive transport systems open for reinforcements and strategic retreats, though they did not have the troops to do this effectively while fighting on two fronts—an urban insurrection and the Allies encroaching from the West.* So leaders on both sides, within and without Paris, were on tenterhooks, watching carefully to see how the drama would play out and what the other side was going to do.

As for their control of Paris, the Germans had not been reassured by the celebrations of July 14, Bastille Day. An archivist and member of the Communist underground, Edith Thomas, describes in a pamphlet she wrote right after the war how surprised she was when she walked outside that July morning. She noticed first that the colors blue, red, and white seemed to be everywhere. Every store window had decorations in those hues; many passersby were wearing the colors either in their lapels or in their hair, or they were wearing blue, white, and red clothing. “La Marseillaise,” it seemed, was being sung on every street corner. Accordionists who played it were surrounded to the point where they feared being overwhelmed by their compatriots. Pedestrians coalesced into crowds that walked boldly up and down the broad boulevards, still empty of all vehicles except for those carrying German soldiers to and from the Normandy front. Their wait for liberation seemed to be over, yet there was no news about the Allied advance (at this point, the Germans were still mounting a vigorous attempt to keep the Allies locked in pockets only a few miles from their disembarkation points; it would be two more weeks before their defenses broke and the Americans would begin their rapid march through north-central France). That memorable July 14, more than a thousand Parisians loudly gathered in the Place Maubert, a well-known site for massive popular political demonstrations before the war, just down the Boulevard Saint-Germain from the Sorbonne, singing and waving improvised French flags. “The [Parisian] police arrive. Someone cries: ‘They are ten; we are ten thousand!’ Faced with such resolve, the officers pulled back.… At the Porte de Vanves, a bonfire was built, and Hitler was burned in effigy.”5 Thomas surmised that there was not a strong reaction from either the Vichy police or the Occupation authorities because they were cautious about touching off an insurrection in an increasingly moody city. In fact, the insurrection that would break out a month later, on August 19, was still in preparation, and those who would lead it were far from capable of taking on even the less formidable German military still in the city. There may have been thousands of FFI and independent guerrillas in Paris in late July and early August, but they had few arms and other materiel for sustained street fighting. The insurgents had stolen, and would continue to steal, arms from isolated German units, but their harvest was composed mostly of pistols; they had some caches hidden underground all over the city, but their armaments were certainly insufficient to stand against the light and heavy machine guns, artillery, and armored vehicles of their Occupiers, regardless of the latter’s diminishing morale. The Allies had refused to parachute armaments into such a labyrinth, fearful, of course, that they would fall into wrong or—perhaps worse—untrained hands.

On the surface Paris remained surprisingly calm in late July and early August of 1944. But still, Parisians could sense a building tension.

The Beast of Sevastopol Arrives

The Beast of Sevastopol. (© Roger-Viollet / The Image Works)

The Siege of Sevastopol, in the USSR’s Crimea, had been murderous for both sides. Dietrich von Choltitz, scion of an old Prussian family, had led troops that had finally broken the siege in July of 1942. The city had been bombed and shelled mercilessly, and when Paris learned that Hitler had personally selected the “Beast of Sevastopol” as the new general in charge of the defense of Paris, a collective chill could be felt. As it turned out, von Choltitz had only a fortnight to keep the city open for the military, to contain the still disorganized French Resistance, to obstruct the Nazis who wanted the city razed, and—as if that were not enough—to effect an armistice with the Allies, especially the de Gaulle government. In his memoirs, he describes his first and only meeting with Hitler, who had decided to appoint him to this prestigious position. The Führer, still recovering from the attempt on his life, was almost incoherent, his body shaking, his spittle spraying the nonplussed general’s face and uniform, as he demanded that Paris be saved from the Allies at any cost. Rather than feeling gratified that, after long and successful service to the war effort, he had been awarded a major position, von Choltitz soon knew that the job was only temporary, for the Reich was on its way to destruction. Nevertheless, this assignment was still in theory the culmination of any general officer’s career, a chance to show the world that only the Germans could protect the “capital of Europe.”

Unaware of how tenuous the German position in Paris was, he was surprised on his arrival on August 9 to find that a partial evacuation of the city had already been quietly prepared. Nonmilitary personnel, especially the women who served as assistants, would be the first to return to Germany; any man who was minimally qualified to carry arms would be dragooned into service. The experienced commander could see that only hollow defenses stood between his command and the Allied onslaught. Extensive Allied bombing had also stopped the import of foodstuffs to the city; the Germans had large warehouses filled with food, and von Choltitz did release some of it for the population to keep them from rioting. But Paris would be starving well before the Allies arrived if something was not done to clear the Seine and the roads so that more supplies could get through. Less concerned with an insurrection than with the massive Allied advance from Normandy—and with keeping Paris from being surrounded so that German troops, including his own, could not retreat—von Choltitz sought to buy as much time as he could. One of his first acts was to gather all uniformed men, vehicles, and artillery and march them down the Avenue de l’Opéra to impress on the Parisians that the Wehrmacht was still there, still ready to defend itself and Paris. He arranged for the first lines of troops to loop back and march again down the avenue so that Resistance spies and Parisians would think he had a larger force than in fact he did. The Swedish consul at the time, Raoul Nordling, tells us that von Choltitz sat in a café on the Place de l’Opéra to watch the reactions of the Parisians to this last German parade in their city.6

Von Choltitz’s orders had been clear: “Paris must lose in a minimum of time its character as a port of call with its unhealthy symptoms. The city must not be a reservoir for refugees and cowards but an object of fear for those who are not loyal citizens, ready to help our troops who fight at the front.”7 But on his arrival, the Prussian general had recognized immediately that his demoralized, badly disciplined, undertrained, and underarmed cohort of troops, many of them aging reservists, was a straw force at best, even with the support of a massive antiaircraft armory. (The Germans had always overprotected Paris from air attack, though no major bombing was ever unleashed on the city.) Hitler’s rabid orders would be easier given than carried out. Desperate looting had by now become standard procedure among his command; almost immediately he had to send out officers to stop retreating Germans from commandeering French vehicles and using them to escape from the city with their stolen goods. The evacuation of the hundreds of women auxiliaries—the souris grises (gray mice)—was an early and encouraging sign to the Parisians that the Occupation was winding down.*

The French railway workers went on strike on August 10, the day following von Choltitz’s arrival, and the French police, finally, did the same on August 14. At this point, von Choltitz asked through intermediaries such as Nordling that there be a “live and let live” policy as his troops evacuated the city. In other words, if not fired on, the Germans would not retaliate. Simpler said than done. The order that von Choltitz could still demand of his own troops was not mirrored in a fundamentally disorganized Resistance. For a bit, von Choltitz’s truce held; one witness noticed that German trucks would pass others filled with Resistance fighters, neither glancing at the other for fear that a firefight might explode into a major conflagration. Rather incredibly, and certainly suddenly, it seemed that the Occupation was ending quickly and more peacefully than had been hoped.

But significant numbers of young Parisians, with little or no leadership or coordination, were stealing arms, erecting barricades, making Molotov cocktails, and physically harassing a beleaguered, very frightened German military. The police had taken control of their own mammoth headquarters on the Île de la Cité, ejecting their collaborating brothers and Nazi bureaucrats; they began sending forays out regularly to test the will of the nervous Germans. Suddenly emboldened citizens began throwing objects down onto German patrols, whose anxious soldiers fired at apartments where French flags were dangling from balconies. Increasingly, Germans in uniform went out or patrolled only in groups. Here and there on isolated city streets dead and wounded civilians and Wehrmacht recruits began to appear. Radio communications among the German troops were spotty because of Resistance interference; von Choltitz and the German strongpoints around the city had to resort increasingly to insecure telephone lines. (Miraculously, the Parisian telephone system, soon to be known by generations of study-abroad students as the worst in Europe, continued to function up to and after the battle for the city.)

To his chagrin and disgust, the new commander was told that the SS troops and police under General Carl Oberg were already preparing to leave. When confronted by von Choltitz, Oberg only shrugged, implying that his superb troops were needed elsewhere to defend the Reich, not to hold an already lost city. In an understatement, von Choltitz wrote in his memoirs, “One must not think that playing with the destiny of Paris was an easy job for me. Circumstances had constrained me to a role that, in fact, I was unprepared for.”8 His nearby Wehrmacht colleagues had offered him reinforcements to defend the city, which he deftly refused, recognizing more clearly than they that it would be a useless loss of men and materiel needed for a more important mission: defending the borders of the Fatherland.

Adding of course to the burden of “defending” Paris was Hitler’s demand that von Choltitz destroy much of the city rather than leave it as he had found it. (The Germans derisively referred to such policies as “Rubble Field orders.”) On August 22, general headquarters had sent him orders signed by Hitler: “Paris is to be transformed into a pile of rubble. The commanding general must defend the city to the last man, and should die, if necessary, under the ruins.”9 In his memoir, von Choltitz remembered a telephone conversation he had with General Hans Speidel, chief of staff to the general commanding the defense of France. He had just received the aforementioned order to destroy Paris:

“I thank you for your excellent order.”

“Which order, General?”

“The demolition order, of course. Here’s what I’ve done: I’ve had three tons of explosives brought into Notre-Dame, two tons into the Invalides, a ton into the Chambre des députés. I’m just about to order that the Arc de Triomphe be blown up to provide a clear field of fire.” (I heard Speidel breathe deeply on the line.) “I’m acting under your orders, correct, my dear Speidel?”

(After hesitating, Speidel answers:) “Yes, General.”

“It was you who gave the order, right?”

(Speidel, angry:) “It isn’t I but the Führer who ordered it!”

(I screamed back:) “Listen, it was you who transmitted this order and who will have to answer to History!” (I calmed down and continued:) “I’ll tell you what else I’ve ordered. The [Église de la] Madeleine and the Opéra [to Hitler’s horror?] will be destroyed.” (And now, getting even more excited:) “As for the Eiffel Tower, I’ll knock it down in such a manner that it can serve as an antitank barrier in front of the destroyed bridges.” It was then that Speidel realized that I was not being serious, that my words were only to show how ridiculous the situation was.…

Speidel breathed a sigh of relief and said: “Ah! General, how fortunate we are that you are in Paris!”* 10

The Reich’s occupation of Paris ended on August 25, 1944, as the last bedraggled German units pulled out or surrendered. Early that morning, before von Choltitz’s surrender, a Luftwaffe plane had dropped thousands of leaflets onto the increasingly confident city, still in the midst of forcefully “liberating” itself from Nazi control. The text of this leaflet reveals a first attempt for the Germans to craft the history of their Occupation of Paris, one that Charles de Gaulle would soon try to rewrite. The tone of this text is both exculpatory and pathetic:

FRENCHMEN!

Paris is living through an especially critical time, whether we hold the city or the Americans or the English occupy it soon!

It is a time when the populace is trying to take power, an event that each citizen fears with panic.

Rowdy crowds are guessing when the German troops will leave Paris and how much time there will be before the Allies arrive! A relatively short lapse of time, but long enough to threaten the life of each citizen.

Paris is still in the hands of the Germans!

It is possible that the city will not be evacuated!

It is under our protection; it has known four years of relative peace. It remains for us one of the most beautiful cities of that Europe for which we fight; we will preserve it from the chaos that it has itself created.

Gunshots are trying to terrorize the city! Blood has flowed, French blood as well as German! False nationalist or surely Communist rhetoric seeks to incite the street to riot or to pit citizens against each other.

So far the sources of this discord are controllable, but the limits of the humanity of German troops in Paris are being pushed.

It would not be difficult to bring a brutal end to all this!

Stalin would have already set the city on fire.

It would be easy for us to leave Paris after having blown up all the depots, all the factories, all the bridges, and all the train stations and to close up the suburbs so tightly they would believe themselves under siege.

Given the absence of food, water, and electricity, a terrible catastrophe would occur in less than 24 hours!

It is not to your usurpers or your Red committees that you should turn to in order to avoid such a calamity, or to the American and English troops that are only advancing step by step and who might arrive too late to help you.

It is rather to the humanity of the German troops that you should turn, but you should not push them beyond their patience.

You owe your loyalty to [the German nation], this marvelous source of European culture, and to your respect for reasonable Frenchmen, for the women and children of Paris.

If all this were not sacred to the population, we would have no reason to remain so tolerant.

We warn the criminal elements for the last time. We demand the immediate and unconditional cessation of all acts of hostility toward us as well as between citizens.

We demand that Parisians defend themselves against the terrorists and support their own demands for order and calm so that they can go about their daily affairs.

That and that alone can guarantee the life of the city, its provisioning, and its preservation.

—Commandant of the Wehrmacht of Greater Paris11

I cite this document in its entirety, for it reveals an amazing narrative: the history of the Occupation through German eyes. Doubtlessly it was written to bring about some calm as the Germans were evacuating before the Allied advance. But it also speaks to some of the points raised earlier about how the Germans perceived Paris—repeating, for example, the claim that the Germans had, in their magnanimity, saved Paris from the ravages of the war. The text also sings the familiar song about current troubles coming from the “terrorists”—the Communists—and the power-hungry, thus playing up the real fear of a civil war that might follow a German retreat. As much as the French may have hated their Occupiers, it says, the Germans were better than chaos (especially Bolshevism) and the slow disintegration of Christian civilization. (We should take note that it makes no mention of the regime’s racial policies.)

The flyer’s rhetoric pleads for recognition that the Germans had been valiant stewards of Paris since 1940, that they still have the best interests of the beautiful capital at heart, and that, should chaos ensue, Parisians will regret the absence of such a strict but respectful authority. Few readers of this flyer knew the drama that was then ensuing among General von Choltitz, diplomats, Resistance leaders, and an adamant Hitler, who was insisting that the city’s bridges and other architectural monuments be destroyed. One order from Berlin demanded that “the severest measures [be used] upon the first indication of an uprising, such as demolition of residential housing blocks [and] public executions.”* 12 The Parisian answer had been to barricade the streets and snipe at the retreating enemy, something that had definitely not occurred in the confused days of June 1940. The Occupation had come a long way from Hitler’s parting monologue on the steps of Sacré-Coeur, just four years previously.

“Tous aux barricades!”

“They are getting nearer, those dear ‘they,’ ” wrote young Benoîte Groult in her diary on August 15, 1944, and later on August 19: “ ‘They’ are still here, but the other ‘they’ still haven’t arrived.” She noticed a wary anticipation as Parisians walked through the late daylight: “An operetta atmosphere, with a foretaste of tragedy.”13 For the Parisian, these must have been deeply harrowing days. Transportation was interrupted, as was electricity. People still lined up at food stores, but shipments to and through the city were almost ended. Young armed strangers were appearing in every neighborhood; tracts were being glued to walls; the Germans themselves seemed in constant movement, though at the same time directionless. Rumor was becoming—tentatively—fact.

The most serious threat for the Germans was the combined Anglo-American force moving quickly from the Normandy front toward Paris. Von Choltitz had arranged a brief truce with some leaders of the Resistance while the Germans sped up their plans to evacuate the city. But when Colonel Rol asked for an insurrection to begin on August 19, Parisians turned to their historical memory to call “Tous aux barricades!” (Everyone to the barricades!). For the first time since 1871, streets and intersections were blocked by Parisians. Colonel Rol had distributed a new call to arms: “Organize yourselves neighborhood by neighborhood. Overwhelm the Germans and take their arms. Free Great Paris, the cradle of France! Avenge your martyred sons and brothers. Avenge the heroes who have fallen for… the freedom of our Fatherland.… Choose as your motto: A BOCHE [Kraut] FOR EACH OF US. No quarter for these murderers! Forward! Vive la France!”14

Hundreds of barricades popped up almost overnight, manned—and womanned—by neighborhood residents, played on by children, and generally left abandoned at night, during blackouts. Everything was used for the barricades: kiosks, cobblestones, downed trees, burned-out automobiles, old bicycles, street urinals, benches, and tree grilles. Films show women and men and children digging up cobblestones and macadam and relaying them to each other in long lines to build an improvised rampart across the wide boulevards that Napoleon III’s Paris prefect, Baron Haussmann, had created in the nineteenth century in order to make such structures difficult to construct. Thousands of sandbags, likely taken from former German strongpoints and protected monuments, served to close bridges across the Seine. Those who were at the barricades were dressed in street clothes, uniforms, and even shorts. Some had red scarves around their necks, reminding each other of the color worn by the Communards in 1870. They were armed, barely, with pistols or old rifles; some had helmets, but most did not.

“To the barricades!” (© LAPI / Roger-Viollet / The Image Works)

Other curious Parisians—observers, not participants—surrounded the barricades; there was a general sense of novelty, even gaiety, until the rattle of a machine gun or the appearance of a German tank or armored car chased everyone into a nearby apartment building or café. Children were everywhere; school was out, and nothing was more fun than seeing one’s parents act like youngsters at play. “Public buildings, the Sorbonne, hospitals enthusiastically raised the tricolor. Telephone calls spread the marvelous news from one end of Paris to the other; Champagne was brought out… saved for this wonderful day.”15 The military effectiveness of the barricades was rudimentary, but their presence was a sign to everyone, including the tense Wehrmacht troops, that control of the city was changing hands.

The major questions then became which of the anti-German forces would take over the city and how quickly and effectively the Wehrmacht could evacuate from Paris. The Germans still maintained order, even directing traffic at major crossroads and making threatening gestures at those who booed them or brandished a French flag. But the bloodiest forty-eight hours remained to be played out. Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul, was desperately visiting prisons, trying to save thousands of French political prisoners from being deported or, worse, just shot. Already news had reached Paris that the Nazi commander of the major prison in Caen had executed all his prisoners, even those held for minor infractions or still under investigation. At the same time, von Choltitz was attempting to put up the strongest possible resistance so that he could retire from the city with honor. And both sides were undisciplined, with communications constantly interrupted and everyone hoping to have the last shot at saving the honor of the city or that of the German army. Chaos had to prevail, bloody chaos, and it did, until the morning of August 25. Soon the holiday air that had first surrounded the establishment of the barricades dissipated; defenders began to fall as the Germans finally reacted with deadly force. Groups of the FFI began to appear less cocky as more combatants and passersby fell under the crossfire of the undisciplined opponents. Brave citizens put on Red Cross armbands and ran under fire to rescue those who had fallen. Confusion reigned as Resistance newspapers began to appear with contradictory headlines: PARIS IS FREE OF GERMAN FILTH!; PARIS IS NOT YET LIBERATED!

Still, thousands of retreating, disoriented, frightened, and angry Germans remained within and just outside Paris. Many were isolated from their units, standing guard over an installation or a building that their headquarters had long forgotten. Without uninterrupted communication, they were targets for roving bands of insurgents. Jean Guéhenno remarked in his journal:

Yesterday morning in the Rue Manin [in the northeast 19th arrondissement of the city, near the Parc des Buttes Chaumont]… I noticed two German guards who seemed quite venturesome. Only an imbecile would have put them there, out in the open. There was no mistaking that they sensed danger. With grenades on their belts, their machine guns in their hands, they were terrified, waiting for their imminent death at the hands of a casual passerby who would pull a pistol from his pocket and shoot them point-blank. At quiet moments, they thought of their Saxon or Thuringian homes, of their wife, their children, their fields. What were they doing there, in Rue Manin, in the middle of that crowd that neither loved nor hated them but only wanted to kill them? By eight o’clock that evening, they were dead.16

A documentary made from moving images shot clandestinely during the last days of the Occupation shows the strange atmosphere that reigned during these last two weeks.17 Pedestrians and Parisians on their bikes nonchalantly pass roving tanks, armored cars, and troop carriers as the Germans appear to be deciding how to defend the city. We see a beautiful city, under bright August skies, indulgently waiting for the moment of liberation. Astute editing suddenly introduces gunfire and scenes of the haphazard fighting that goes on in neighborhood after neighborhood. Every type of French citizen appears to participate: teenagers, men, women, poor and wealthy, old and young. But it is especially the moment of the young—sometimes the too young. Jacques Yonnet, in his memoir, described a corpse he glimpsed on the street: “I saw a body [picked] up at Les Halles—a kid in short [pants], fifteen years old at most. He’d attacked a Boche truck that was flying a white flag. The kid was armed with a… pistol with a mother-of-pearl grip, a 1924 ladies’ handbag accessory. The real criminals weren’t in the [German] truck.”18 The real criminals, Yonnet implied, were those who had ordered this mobilisation générale of civilians to confront a still venomous German presence. Debate would continue well after the war about whether the insurrection had been foolhardy or even necessary.

The film shows in detail the arrival of the French Second Armored Division and its US-uniformed soldiers, American-made tanks, and Jeeps. (For some viewers around the world, it appeared that the Americans were the first to enter Paris, but it was a French division, outfitted in American gear.) Images reveal a strange combination of slowly advancing troops surrounded by applauding Parisians in their everyday clothes. It is as if they are at some theme park where the insurrection of Paris is being reenacted; shots are heard, but smiles are everywhere. Soldiers are crouching, checking out apartment windows and balconies, while residents are casually leaning in doorways, smoking, gossiping, and watching. One old gentleman actually claps his hands in applause as soldiers dodge sniper fire. Had Parisians become inured to the sounds of battle and commotion over the past week of the insurrection, or were they just oblivious to the dangers of urban street fighting? What remains unclear is how much of the continuing violence was a result of the actions of French people who were still pro-Vichy and anti-Resistance and how much was the response of German regulars. The so-called Radio Concierge network (concierges passing along news and gossip) continued to function, and word of the advancing Allies was shouted from loge to loge along the streets of both banks of the Seine. Loudspeakers, mounted on trucks and cars, passed by announcing the cease-fire that von Choltitz had agreed to, but it appeared that neither side was willing to stop firing, at least intermittently, on the other.

Erratic activities by both the FFI and the Wehrmacht made walking to work or going to the hospital or even going to church a dangerous activity. In her short history of the Liberation, the archivist Edith Thomas said that going from the Left Bank to the Right Bank for a meeting was like a trek to a remote land. She felt like “a Sioux” moving cautiously in an unfamiliar forest as she passed FFI barricades and roving German tanks. When she ran from doorway to doorway, apartment residents asked if she had news from up the street or around the corner, “as if I had just come from a long voyage.”19

Thomas would eventually get access to the many orders that Colonel Rol had distributed throughout the city—through radio broadcasts, posters on thousands of walls, loudspeakers, and leaflets thrown from fast-moving cars—and they would reveal how well organized, finally, the Resistance had become. Seeking to unite the irregulars with his own well-led cadres, Rol even sent out runners—especially teenage girls and boys—to stand in the crowds that surrounded the posters and listen for those who expressed an interest in joining the fighting. After the gawkers had moved on, the youngsters would follow them around the corner to tell them how they might join up.

Still, most of the fighting was dispersed and only intermittently planned:

It’s impossible to give a description of the battle as a whole. Now it’s a series of local actions, but all aimed at the same goal: to annihilate the enemy. Automobiles against tanks, Boulevard de la Chapelle, Boulevard des Batignolles, Avenue Jean-Jaurès, Rue de Crimée…; arms taken from the enemy: a Renault tank, two Tigers, a truck, munitions, two little autos in the 17th arrondissement. Here and there, Germans are taken prisoner and are astonished that they are not shot by the “terrorists,” [astonished] to see these men without uniforms, these civilians, respecting the laws of war that they themselves had so badly followed.20

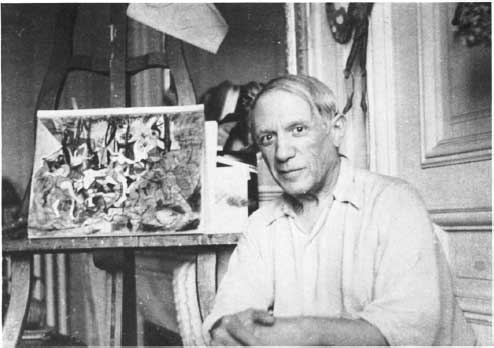

Our nervous friend Pablo Picasso ventured out of his apartment in the 6th arrondissement, after the insurrection had begun, and took up residence on the Île Saint-Louis with his former mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter, and her daughter by him, Maya. His then companion, Françoise Gilot, described his anxiety:

In the last few days before the Liberation, I talked with Pablo by telephone, but it was next to impossible to get to see him. People were already beginning to bring out the cobblestones to build the barricades. Even children were working at the job, especially in the 6th arrondissement, where Pablo lived… where there was a great deal of fighting.… German snipers were everywhere. The last time I talked to Pablo before the Liberation he told me he had been looking out the window that morning and a bullet had passed just a few inches from his head and embedded itself in the wall.21

Picasso celebrates the Liberation. (Photograph by Francis Lee)

While waiting for the city to be liberated, Picasso painted a joyously liberating work, The Triumph of Pan, which he told friends he worked on as he listened to the battle going on around him. It depicts a Dionysian festival, one that might celebrate the joy of freedom from want and fear. The work is small and done in watercolor and gouache, but its exuberance belies all the somber work that had preceded it during Picasso’s volitional exile in Paris during the war years. In the words of one critic, “Picasso seems to have equated the reappearance of Dionysus, ‘his epiphany as a bringer of happiness after [a] dark period of hunting and sacrifice,’ with the deliverance of Paris and, by extension, the world after the great sacrifice symbolized by the war.”22

While painting, Picasso must have wondered: What is going on? Who is winning? Are the Germans regrouping? Where are the other Allies? Jean Guéhenno gives a tersely vivid account of trying to cross the Seine and finding himself trapped near Les Halles, the great marketplace on the Right Bank: “German tanks were patrolling. As I was trying to get across the Boulevard de Sébastopol, one of them began firing only thirty meters from me, decapitating a woman and gutting a man. On side streets fifty meters from that scene, strangely enough, people were sitting on their stoops gossiping. Curiosity and joy are at their strongest.”23

The city had become a patchwork of violence mixed with celebration, both sides firing indiscriminately not just at each other but also into crowds. The passions of the last four years had created an explosion of fury, misdirected and unable to distinguish combatants from tired and frightened citizens. Many Parisian civilians were fearless. Running openly into crossroads, they would tear down the innumerable German-language signs that had decorated their city for more than four years. Film clips show that not all the panels were destroyed; some were taken off as trophies and are probably still in attics and wine cellars across Paris.*

Such small dramas filled the forty-eight hours that separated the erection of the first barricades, the first openly defiant insurgency against the Occupation, from the late-night arrival of the first French-manned tanks of the Second Armored Division, which had rolled through the city’s Porte d’Orléans. Carrying the first French soldiers in Paris since June of 1940, this small tank force, under Captain Raymond Dronne, had sped along the side roads and backstreets of the suburbs, crossed the Seine by the Pont d’Austerlitz, and driven along the quays on the Right Bank to reach the Hôtel de Ville just before midnight on August 24. Few Parisians knew this, for curfews had prevented them from leaving their homes, and the still Nazi-controlled radio only reported what seemed to be repeated instances of successful German defense against the victors of Normandy, who were trying to reach the city. But everyone heard the giant bells of Notre-Dame begin to ring, something they had not heard since the Occupation had begun.

Even after the Germans had surrendered or left, small battles still were occurring throughout Paris. By then the fights were part of a civil war between the FFI and remnants of the Vichy Milice. Uniforms did not distinguish the combatants; the Milice had changed into civilian clothes, some even putting on FFI armbands as a disguise. Among the latter were not only last-ditch supporters of the Vichy regime but also young men trying to escape Paris alive, to return to their homes in the countryside. No one knew whom to trust, and despite de Gaulle’s appointment of General Pierre Koenig, Gaullist commander in chief of the FFI, as military commander of Paris, disorder would rule the streets for a few more days.

On Saturday, August 26, Berthe Auroy, our schoolteacher who lived in Montmartre, had gone to the Champs-Élysées to watch de Gaulle strut in victory down the grand avenue.* Everyone was excited, laughing, dressed as if for Bastille Day in all sorts of blue, white, and red regalia. On her way back along the Rue de Rivoli, she and her sister heard machine-gun fire and the whistle of bullets. The FFI irregulars yelled at everyone to lie on the sidewalk, to keep their heads down. Then, at a break in the firing, they urged the frightened crowd to run for the Jardin des Tuileries. But inside the garden’s gates, the firing continued, and Auroy and her sister again ran, fell to the ground, got up, and ran a few more yards, until they reached the Louvre. There they saw a group of people in a line, seeking refuge, with the aid of a ladder, via a service entrance; someone had broken a large windowpane, and the civilians were climbing into the museum. Berthe and her sister ascended to find themselves

before one of the grand staircases of the museum. We sat down on the steps. It was calm there, and we were comfortable on the beautiful carpet. We stayed there a good bit of time, then we risked going outside, and hid next under a grand entry arch of the Louvre. We couldn’t leave before we were carefully searched.… We climbed over the benches that had served as barriers, and we went back up to Montmartre using narrow side streets, where, now, nothing bothered us but a few isolated gunshots.24

With the arrival of Leclerc’s division, there were touching scenes of French men and women being reunited after long separations. The soldiers and officers who were Parisians themselves jumped off their motorbikes and tanks to run into the nearest café to call home: “Mom, I’m coming; I’m almost in Paris.” One writer described a scene in which a young tanker sees his father in the crowd of Parisians yelling their pleasure at seeing their liberators. “That’s my papa,” he screamed; jumping from his vehicle, he ran up to the stunned elder man. The father just stared, then grabbed his son’s cheeks with both hands and pulled him so close and so tight that bystanders had to separate them. Scenes like this, often filmed and photographed, justified de Gaulle’s canny insistence that the first Allied troops to enter the capital be French.*

Von Choltitz surrendered three times on August 25 before he was spirited off to England, then to a prison camp in Mississippi, of all places. The first time was at the Hôtel Meurice, on the Rue de Rivoli, where the military commander of Paris had been installed since June of 1940. Von Choltitz had ordered his guards to put up a modest resistance before giving up the building; when French irregulars burst into his office, one demanded awkwardly: “Sprechen Deutsch?” Von Choltitz, who had laid his arms on his desk, answered suavely: “Yes. A bit better than you.” He was taken by a French tank commander to the Préfecture de police, where he officially surrendered to General Philippe Leclerc, commander of the Free French Second Armored Division. Von Choltitz knew he had lost the city when, the evening before, he had heard the great bells of Notre-Dame Cathedral ringing for the first time since the Occupation began, signaling a new day in Paris. Soon every church bell in the city was vigorously pealing. The general had picked up his phone and called General Speidel at the Wehrmacht headquarters near Soissons, some fifty miles north of Paris; putting the receiver up to the window, he said: “Please, listen. Did you hear?” Speidel replied, “Yes; I hear bells.” Said von Choltitz, “You heard well: the French-American army is entering Paris.”25 Finally, von Choltitz was taken to the Gare Montparnasse, the major railway station on the Left Bank, to sign official papers and an order that all German resistance cease. That order had to be transmitted by means of loudspeakers mounted in Jeeps that went to all the strongpoints left in the city. The last fortress, at the Palais du Luxembourg, finally surrendered at midday on August 25. Paris was liberated.

French soldiers are first into a liberated Paris. (Musée du général Leclerc de Hauteclocque et de la Libération de Paris / Musée Jean Moulin EPPM)

Von Choltitz came out of all of this with shining colors, more than any other German leader of Paris during the Occupation. Though he manufactured much of his legend (“I saved Paris for the Allies!”), his patience and sangfroid most certainly kept France’s capital from being severely damaged during those hectic two weeks. Nevertheless, he had approved the deportation of more than three thousand political prisoners just a week before the surrender, and members of the Gestapo, at least those who had stayed until the last minute, were still tailing, arresting, and torturing “terrorists,” including those they would massacre in the Bois de Boulogne. In addition, among the reasons why Paris was not demolished were that General Speidel had refused to order the Luftwaffe to bomb it, and, fortuitously, perhaps, that von Choltitz did not have the personnel or the materiel to do the massive destruction demanded by Hitler.*

Why Do Americans Smile So Much?

The anonymous authors of the United States Army’s Pocket Guide to France were quite aware that Paris would be one of the major attractions for the soon-to-be-victorious GIs. “If you get to Paris, the first thing to do is to buy a guide book, if there are any left after the Nazi tourists’ departure. Paris is in a sense the capital of Europe and regarded as one of the most beautiful and interesting cities in the world. We don’t know just what the war has done to Paris. These notes will assume that there’ll still be lots to see.”26

By the time the Americans had arrived in the almost German-free Paris, most of the street fighting had ended. Most of the Germans and their Vichy Milice supporters had been captured, wounded, or killed. Many of the captured were the bureaucrats who had overseen the Occupation, pouring out of the elegant Meurice, Majestic, Lutétia, and Raphael hotels at the first sign of the FFI or French soldiers entering their lobbies. There are reports that some patriotic Nazis fired on their more pusillanimous fellows as they crowded through doors, hands raised. Anywhere from one thousand to 1,500 résistants and Parisian citizens died, and about 3,500 were wounded. About 130–150 members of the Second Armored Division were killed or died from wounds after the Liberation; they also lost a large number of tanks, half-tracks, and materiel, which shows that the Germans were not totally ineffective. Estimates of the number of Germans killed range from 2,500 to three thousand. The battle for Paris was not one of the major urban confrontations of the war, but it was not a skirmish, either.27

De Gaulle had insisted that the first Allied forces to enter Paris be French, and they were, as noted, the legendary Second Armored Division (Deuxième Division Blindée).* They had been heavily outfitted by the Americans and were driving American tanks and trucks, wearing American uniforms and helmets, and carrying American gear. Thus, for the first time, Parisians saw close-up not only their victorious soldiers but also the significant role that the Americans were playing in the liberation of their nation. One of the most meaningful filmed events of the liberation of Paris occurred a day after de Gaulle had marched triumphantly down the Champs-Élysées: the American Twenty-Eighth Infantry Division and Fifth Armored Division, trooping the same path.* This American show of force drew huge crowds; their enthusiasm brought smiles to the faces of the soldiers who had just endured the rigorous Normandy campaign and who would be involved in major battles for the next eight months as they made their way to the Rhine and into Germany. Grins and grit, the air of confident vigor, sent a clear message to the world: the Americans were in Europe to stay, not because they were imperialists but because without them Europe would have disintegrated.

And then came the Americans. (Creative Commons)

All the same, there was distrust on both sides of the ledger. Had not French soldiers let the Wehrmacht roll over them in just a few weeks in 1940—and then sheepishly gone off to prison camps? Had they not left their wives and children behind to fend for themselves during the harsh Occupation? The Americans still did not have much respect for a country that had been so docile in defeat, and most viewed French culture as immoral. Officers reminded their men constantly that French girls were “too easy” and that they should be careful to avoid catching something. In return, the French still remembered the World War I American doughboys’ rough impatience with their mores. And almost immediately, the presence of American soldiers in Paris brought tension between them and the FFI irregulars. There appeared, in the opinion of the latter, to be a masculine entitlement on the part of the GIs, a strong hint that Paris and France now needed to be “remasculinized” in the image of a virile, conquering, confident, and smiling army. More important, the news brought to Paris by refugees from the Normandy front, where thousands of civilians had been hurt or killed and where whole city centers had disappeared, suggested the Americans had been rather careless in their bombing. Finally, stories—true and exaggerated—of the exuberant Yanks in their Jeeps, looting anything not nailed down, and their rough treatment of French women, including multiple episodes of rape, attenuated some of the joy at seeing these sons and grandsons of the First World War doughboys, who themselves had been especially rambunctious. Yet for the most part, the appearance of this new, powerful army temporarily overcame these differences as the French joyfully jumped on tanks and trucks to kiss, embrace, and give gifts to the Yanks. And after all, weren’t they “sexy,” an erotic observation enhanced by their apparent innocence?* 28

“Le peuple français est bon et joli!” (The French people is good and pretty [sic]), yelled an American soldier awkwardly when a French microphone was put before him as he entered Paris. The American army only spent a few days in Paris after its liberation, but the memory of those healthy, young, and always grinning men, marching with a certain nonchalance in contrast to the memory of the rigidly disciplined Wehrmacht, would have a lasting effect on Paris’s collective memory of those joyful days. One of the Groult sisters wrote amusingly about seeing her first “liberator,” a blond, blue-eyed architecture student named Willis. Flora watched him from her balcony as he asked her neighbors in broken French for a place to get a bite to eat. She rushed down and in perfect English asked him up for a meal. Her mother and sister found him casual, intelligent, charming, and, for the first time in years, they felt comfortable talking to a man in uniform. Having been given permission to wash up, he casually removed his shirt in front of the women, all of whom noticed his white complexion, sunburned neck, and gently muscled chest. “[After his ablutions], we sat down to supper, and he ate without knowing it one of our last eggs. How could he have guessed, this little conqueror, that we only had four left?”29 Obviously, Willis had not read, or had forgotten, the admonition that could be found in the Pocket Guide to France, distributed by the millions to young Americans at the time of D-day:

If the French at home or in public try to show you any hospitality, big or little—a home cooked meal or a glass of wine—it means a lot to them. Be sure you thank them and show your appreciation. If madame invites you to a meal with the family, go slow. She’ll do her best to make it delicious. But what is on the table may be all they have, and what they must use as leftovers for tomorrow or the rest of the week.30

After dinner, the sisters delightedly climbed into his Jeep, and the proud GI drove them around a Paris still delirious with the scent of freedom. The next day Willis came back with packages of bacon and stewed beef, but then he suddenly left Paris, and for good, off to continue the fight against a retreating but still dangerous Wehrmacht. “They are different, these free men, with their sun-browned skin, their innocent looks, rolled-up sleeves, who fight, kill, spend a little time with you, then leave.”31 Many of her contemporaries would wonder how an army so casually disciplined could have been so successful against the rigorously disciplined Germans. And they smiled so often and so spontaneously!

Berthe Auroy wrote about meeting her first Americans in early September, well after the “war of the rooftops” between the FFI and the remnants of Vichy resistance was over. Walking down to the Place de Clichy (then, as now, a center for nightclubs, sex shops, and open prostitution), she met three American GIs. “I asked them to climb up the Butte [Montmartre] with me. Two were pink and chubby-cheeked, like babies, and the third had big, very American teeth and glasses.”32 Not unlike the young German soldiers who saw Paris on leave in July of 1940, these Yanks had a day pass to visit the city, which they had found stunning. In fact, many American soldiers, having marched through dozens of towns and villages damaged by the war, were surprised at how “whole” Paris was, how few were the signs of the conflagration that was going on around it. The next day, Auroy went to the Champs-Élysées to see an American encampment; there she was struck by how friendly these “giants” were and embarrassed at the sight of her countrymen reaching to grasp the cigarette and gum packages thrown to the crowd. Yet, she remarked how nice it was to see the cafés filled with the (yes) smiling, laughing, friendly young men in khaki and how relaxed the French patrons sitting near them were, a state of affairs that Paris had not experienced for more than four years.

Much younger than Berthe Auroy, and much more interested in flirting, the Groult girls were also astute analysts of what it was that made the Americans so different. First was the endless supply of canned goods, condensed milk, chocolate, and cigarettes they distributed with abandon. Every American invited into a Parisian home brought with him evidence of the wealth of that faraway country. An enormous war machine most likely bolstered their naive self-confidence. And indeed, the Yanks were patronizing; after all, the United States was once again rescuing Europe from its own excessive incompetence. Yet the GIs were touched and amused by the generosity of those they had “liberated.” Civilian and army journalists were expansive in their coverage of how the GIs had been embraced by the delirious French. Flora Groult attempted to explain:

Tall, big men, we are relieved of every vain worry in your presence. You climb the stairs to our apartment, our doors are open, you bring packages, all as it should be. That’s it, the overwhelming advantages behind which you hide your weaknesses. And what are they? No inferiority complex about their inferiority. They say: “I don’t much like that!” (Literature, music, art…).… They manage so well the immensity of their ignorance, as if it were a light feather.…33

The Parisians were bedazzled, but still held on to an old European view: Americans are strong and rich, but without the culture that Parisians still treasure. The images that immediately came back to the United States via the great magazines Look and Life, plus the newsreels shown weekly in American movie houses, emphasized the affectionate response of French women and girls to the arrival of Americans. The rapturous delight of children reaching out their hands for chocolate and chewing gum were also a photographic staple. Americans were not only liberating; they were showing the expansiveness of the culture and mores of the United States.

One of the first Americans into a liberated Paris was the incorrigible Ernest Hemingway, officially there as a correspondent for Collier’s magazine.* Hemingway had finagled himself onto one of the LSTs (landing craft able to carry men and large machinery, including tanks) that were in the first wave approaching the Normandy beaches on June 6, but the Allied command did not allow him to land with the troops. (His wife, Martha Gellhorn, had been able to land on that day from a hospital ship, a feat for which Ernest never forgave her.) Returned to the mother ship, he had to wait before finally setting his boots on French soil. For the next two and a half months, the macho author acted as correspondent, morale officer, combatant, and overall pest as the Allies broke out of the invasion beachheads and made their way to Paris. Because he was such a well-known writer, and because he was reporting for a massively popular American publication, his version of what happened as the Second Armored Division was mopping up still resonates and, for many, left a definitive record of the emotion that enveloped those who had helped to liberate the capital. We know that Hemingway had already had an emotional relationship with the city; A Moveable Feast, published after his suicide, in 1961, tells us that. His almost valiant attempt at being among the first Americans into the quasiliberated capital speaks to the sentimental value that the capital had for him. “I had a funny choke in my throat and I had to clean my glasses because there now, below us, gray and always beautiful, was spread the city I love best in all the world.”34 There he had been a beginner, a newlywed, an impecunious writer; now he was a famous author, a hero, and he could return to—and in his own way help liberate—the place that had given him the independence every writer needs.

The Americans brought more than military liberation. Their casual acceptance of French enthusiasm, their obvious pleasure in being kissed and hugged by thousands of French girls, their distribution of candy, cigarettes, and chewing gum (still the term used by the French for this delicacy), their lack of ideological fervor, their protection of German soldiers and bureaucrats who had fallen under their authority, their obvious joy at being victorious: all these signs created an image of a nation ready to help its wounded cousin recover, efforts that would continue after the war with loans, reconstruction funds, and eventually the very generous Marshall Plan. On the other hand, American soldiers did loot; they did attack women; they often showed little respect for French custom, but at the same time they reminded the French of what absolute and unquestioned freedom could be. It was as if they were saying: “We’re free. It’s fun. Come along. We’ll help you get there again.”

And then there was the Jeep, first produced in 1942—the emblem of American industrial ingenuity. One of the most memorable photographs of Americans in a liberated Paris shows two soldiers in a Jeep coming up the stairs from a Métro stop. They had obviously backed the Jeep down the steep steps so that they looked as if they were emerging from the underground. They have huge smiles on their faces as they tease the Parisians into believing for a moment that they had done the impossible. Paris suddenly found itself under a new version of occupation, much more benign but ultimately more influential and long-lasting.

Whodunit?

On April 26, 1944, only four months before the liberation of the city, Maréchal Philippe Pétain had visited Paris for the first and only time as chief of state of the Vichy government. The crowds had been moderate but enthusiastic, as contemporary photographs reveal. (Schoolchildren had been given the day off.) Speaking at a lavish dinner in the Hôtel de Ville that evening, the elderly statesman offered, “This is the first visit I have paid to you. I hope that I will be able to return soon to Paris without being obliged to inform my [German] guardians… I will be without them, and we will all be much more at ease.”35 Even at this late date, there had been many who were still confident in the doughty old man’s leadership. Indeed, until the Liberation, there were those who seriously believed that he and de Gaulle would eventually meet, shake hands, and together bring France back from the destitution and division of four years of war and the Occupation. Pétain himself had wanted to go to Paris once it was liberated, but his German handlers forbade it, spiriting him and his close cadre off to a castle in Germany, where they remained until the end of the war. On August 26, only four months after this triumphant visit, a determined Charles de Gaulle would enter the Hôtel de Ville and stand in the same spot as his former commander to declare that Paris once again belonged to its citizens.

The Liberation of Paris had filled the world with exultation. Spontaneously, “La Marseillaise” would be sung around the world in plazas, on avenues, in offices, in movie houses, even in legislatures. No event, except the end of the war itself, would receive such widespread notice and occasion such joyous expressions of relief and happiness. Their capture of Paris had given the Nazis a great propaganda victory and had convinced the world that the Third Reich was a force that would last—if not a thousand years, then at least a few decades. Their subsequent loss of Paris, as the Allied armies streaked across northern France and wended their way vigorously up from the south, seemed to put the imprint of final and total victory on a horrific conflict that had lasted for five years. But the liberation of the city had come at a cost to the plans of the Allied command. Generals Eisenhower and Bradley had been correct: taking the capital of France had slowed the advance of their motorized armies. Precious fuel supplies had been depleted; diverting troops to encircle and take the city had weakened their advance units. As a result, the Germans were able to retreat in some order to the Siegfried Line (a major series of fortifications on the border of France and Germany) and hold off the invasion of their homeland for another six months. Was Paris worth the Battle of the Bulge and the other major last-ditch efforts of the Reich that caused hundreds of thousands of military and civilian deaths? This unanswerable question is almost never asked, for the Liberation of Paris was such a major symbolic victory of the forces of good against the legions of evil.

Yes, in the end, de Gaulle took most of the credit for having saved Paris on behalf of the “French people.” The Pocket Guide to France sustains this myth. We should admire the French, it admonishes its naive readers: “The French underground—composed of millions of French workers, patriots, college professors, printers, women, school children, people in all walks of life of the real true-hearted French—has worked courageously at sabotage of Nazi occupation plans.”36

“Millions” is a strong exaggeration, but more important than the number is the idea that most French people had withstood the blandishments of the Vichy regime (which is mentioned only once, glancingly, in the brochure) and, more important, the propaganda and brutality of the Reich. Charles de Gaulle himself could not have written a better history. (Who knows? Maybe he did write it, since the “authors” of this document have remained anonymous, listed simply as the “War and Navy Departments, Washington, D.C.”)

For years after the Liberation, arguments over memorials, laws and edicts, reparations, and political representation would divide the political classes of France. The Communist Party of France would lead one of its largest propaganda campaigns in an attempt to accumulate as much recognition for the Liberation as they could. Former Vichy supporters, a resurgent Catholic Church, and former résistants with all sorts of ideologies—including those who had followed de Gaulle into exile and those who had stayed on the soil of France—would vie for the right to call themselves liberators of the City of Light and maneuver to capture for themselves the glorious residue of that great symbolic event.

All this commotion raises the question: Who did liberate Paris? The Allies, the Communists, the ragtag FFI, de Gaulle’s Free French troops, and even the insurgent citizens of Paris wanted a stake in the answer. As we have seen, even the German commander of Gross Paris wanted some recognition for his role in “liberating” the city. The liberation of Paris was made possible by an overlapping combination of events, military and political decisions by a formidable mix of personalities, and the spontaneous participation of a long-repressed population. Train and transport workers went on strike; the police gave up their loyalty to the Vichy regime and its German supporters; armed irregulars of the FFI, strongly supported by the Communists but comprising many ideologies, united; Leclerc’s eager Second Armored Division fought bravely through German defenses to reach the crown jewel of French nationhood; and the massive support of the American army provided an invaluable backstop.*

For a few brief days, as one historian has pointed out, “La Marseillaise” and “The Internationale” were joined together as the liberated Parisians celebrated not only the departure of the Germans but also the end of the Vichy regime, and perhaps, just perhaps, a truly radical break with the past, one not unlike the great Revolution of 1789.37 Gertrude Stein described the euphoria:

And now at half past twelve to-day on the radio a voice said attention attention attention and the Frenchman’s voice cracked with excitement and he said Paris is free. Glory hallelujah Paris is free, imagine it less than three months since the landing and Paris is free. All these days I did not dare to mention the prediction of Saint Odile [patron saint of Alsace], she said Paris would not be burned the devotion of her people would save Paris and it has vive la France. I cant tell you how excited we all are and now if I can only see the Americans come to Culoz [the tiny village where she was living] I think all this about war will be finished yes I do.38

Soon the optimism dissipated as the factionalism that had torn France apart for years, both preceding and during the war, began again to dominate. Most of the world, though, was unaware of these dissensions; what counted for all who loved Paris was that the city was back in the hands of the French, who had risen up to wrest their capital from an evil empire. And, miraculously, the city on the Seine seemed to have suffered very little, especially when compared to the terrific desolation of so many of Europe’s capitals. What the world did not see was the economic, social, and psychological damage wrought by the Occupation, which would take years to repair.