CHAPTER 12

Sleep: The Student Body at Rest

A ruffled mind makes a restless pillow.

—Charlotte Brontë

In our 9:30 a.m. class, we’ve seen them all. The face-proppers—elbows on desk, chin resting in their hands, gazing at us without blinking (transfixed or trance? We’re never sure). The mannequins—caps pulled down to conceal their closed eyes (um, you know your fingers have been motionless on your laptop keyboard for thirty-eight minutes, right?). The survivalists—half a dozen energy drinks lined up in front of them like tequila shots in Cancún (are those three Red Bulls just for the next hour, or all day?).

To be honest, we didn’t need empirical data to convince us that students are getting less sleep than ever just when they need it the most—but we have it here anyway. Students today sleep an average of one full hour less than their peers forty years ago. Only one-third of undergrads think they consistently get a good night of rest. Twenty percent of students report pulling at least one all-nighter every month, but being able to survive the next day is not the same as thriving: inadequate sleep results in worse academic performance, greater anxiety, and higher incidence of depression. It also causes you to retain less of what you learn, which is why we say that students who don’t get enough sleep are renting their education, not buying it.

How much sleep should you be getting? The definition of sleep deprivation is anything less than seven hours, and most authorities say the average adult should be sleeping between seven and nine every day. But that being said, what works for you? If you get ten, eight, or six and a half hours (which is the national collegiate average) and you feel you are at your best, that is how much sleep you should be getting. If you sleep six but then take a long nap during the day, that may be what works for you. In this chapter, we aren’t going to tell you how much to sleep, but we will explain how to figure that number out for yourself. We are going to discuss the why and how of sleep, explain what is going on in your brain when you shut down your body, and cover how you can take advantage of the right amount of zzzs to feel, think, perform, and even look better.

A Riddle: When Do You Crash Because You Don’t Crash?

When you find yourself nodding off mid-exam, it’s no surprise that you awaken to a lower GPA, but imagine falling asleep and waking a few minutes later to find that you had spilled 38 million gallons of oil in the ocean. How about coming out of a sleep-induced haze to find that you had blown up a nuclear power plant? Sleep-related issues were the cause of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, Three Mile Island (worst nuclear disaster in the United States), Chernobyl (worst nuclear disaster in history), and even the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger. Now, you might be thinking that you are never going to drive an oil tanker or operate a nuclear facility, but you are probably going to drive a car, and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that each year there are 100,000 sleep-related crashes, with an estimated 1,550 deaths and 71,000 injuries. If you are still wondering how this applies to you, one study found that 67 percent of undergrads reported being drowsy at the time of an accident, and 17 percent have fallen asleep behind the wheel of a car. Stopped at a red light while returning from an overnight shift during medical school, Alan fell asleep. It seemed like a blink, but when he opened his eyes he realized he had moved through the light into the intersection. Not only was he lucky to be alive, but so were the two passengers in his car. Alan never drove to his overnight shifts again, but he tells this story to his patients, asking them, “What will it take for you to take your sleep seriously?”

Check this one out, my all-night-driving friends: driving with fewer than four hours of sleep is the cognitive equivalent of driving while intoxicated. Just like some drunk fools think they are the funniest, wittiest, or cleverest folks alive, sleep-deprived people often think they are doing an awesome job when in reality, they are seriously impaired. Between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, your body can bounce back from some serious sleep-induced damage, but your best judgment doesn’t share that resilience.

Not getting sufficient sleep has some serious downsides. As Tyler Durden notes in Fight Club, “With insomnia, nothing’s real. Everything is far away. Everything is a copy, of a copy, of a copy. When you have insomnia, you’re never really asleep and you’re never really awake.” The physical and emotional harm caused by lack of sleep is so severe that sleep deprivation is considered a form of torture, outlawed by the Geneva Conventions.

We don’t know exactly why, but all species, from insects to kangaroos to humans, need to sleep or they die. Death, oil spills, and lower GPAs aside, lack of sleep has a profound effect on your ability to thrive. There are many reasons to get a good night’s sleep, but here are a few not to get a bad one:

Sleepy and Grumpy: Sleep deprivation has a rather nastily selective impact on memory: you forget the good and remember the bad! When shown a list of both positively and negatively oriented emotional words, people who are then deprived of sleep remember 80 percent of the negative the following day, but only 60 percent of the positive ones. It is well known that depressed people sleep poorly, but it is now also understood that if you don’t sleep, you’re more likely to get depressed. So if you want to make the most of those precious positive emotions, go to bed.

Sleepy and Grumpy: Sleep deprivation has a rather nastily selective impact on memory: you forget the good and remember the bad! When shown a list of both positively and negatively oriented emotional words, people who are then deprived of sleep remember 80 percent of the negative the following day, but only 60 percent of the positive ones. It is well known that depressed people sleep poorly, but it is now also understood that if you don’t sleep, you’re more likely to get depressed. So if you want to make the most of those precious positive emotions, go to bed.

Eyes wide shut: Assessing reality is tough enough (“Does she really like me or was she just trying to be nice?”), but when we don’t get enough sleep, our worlds can turn into fantasylands. One group of students at Bradley University was forced to pull all-nighters while the other half got a solid eight. When tested on the same material the following day, those who had been awake for twenty-four hours rated themselves as having better concentration, greater effort, and better performance than the group who had slept through the night, and yet the results showed the exact opposite: despite feeling more capable than the sleepers, the all-nighters scored 35 percent lower. You’ll likely have to pull some all-nighters in college, but don’t fool yourself: no matter what you think, you need to close your eyes to really open them.

Eyes wide shut: Assessing reality is tough enough (“Does she really like me or was she just trying to be nice?”), but when we don’t get enough sleep, our worlds can turn into fantasylands. One group of students at Bradley University was forced to pull all-nighters while the other half got a solid eight. When tested on the same material the following day, those who had been awake for twenty-four hours rated themselves as having better concentration, greater effort, and better performance than the group who had slept through the night, and yet the results showed the exact opposite: despite feeling more capable than the sleepers, the all-nighters scored 35 percent lower. You’ll likely have to pull some all-nighters in college, but don’t fool yourself: no matter what you think, you need to close your eyes to really open them.

Sleepwalking Through College

If sleep improves our memories, enhances our thinking, and benefits our health, why are so few students getting it? And it’s not just college students who are suffering. Here are a few reasons Americans are sleeping two full hours less every day than they did just a century ago.

24/7 society: With unlimited artificial light, people work longer, and with constant access to the Internet, they play longer, too. It’s harder than ever to know when to stop. You may not realize this, but there was a time when the campus library actually closed. You couldn’t get in even if you wanted to. Now if you’re not there, you feel guilty.

24/7 society: With unlimited artificial light, people work longer, and with constant access to the Internet, they play longer, too. It’s harder than ever to know when to stop. You may not realize this, but there was a time when the campus library actually closed. You couldn’t get in even if you wanted to. Now if you’re not there, you feel guilty.

Sleep machismo: Some people (aka gunners) love to brag that they don’t need sleep to kill it every day. Making yourself out to be a superhero or a martyr has become common in campus culture. But even though these folks are secretly suffering, they might make you wonder if you shouldn’t try to push yourself further.

Sleep machismo: Some people (aka gunners) love to brag that they don’t need sleep to kill it every day. Making yourself out to be a superhero or a martyr has become common in campus culture. But even though these folks are secretly suffering, they might make you wonder if you shouldn’t try to push yourself further.

Fear of missing out: College is FOMO incarnate. Opportunities ranging from partying to studying, playing it to slaying it, and everything in between just multiplied by roughly 895 percent. Try to take advantage of everything in college and you may end up sleepwalking through the whole adventure.

Fear of missing out: College is FOMO incarnate. Opportunities ranging from partying to studying, playing it to slaying it, and everything in between just multiplied by roughly 895 percent. Try to take advantage of everything in college and you may end up sleepwalking through the whole adventure.

Sleep and Your Brain

Sleep is so much more than the cure for sleepiness; it allows our brain to create new memories, organize the old ones, and develop. Studies show that sleep has been associated with better judgment, eating habits, focus, learning, attention, and willpower.

Exercise may grow the brain, encouraging your neurons to multiply, but sleep allows them to connect. When you are taking notes in bio, listening to a lecture in English lit, or practicing a move on the field, your brain is encoding a memory; but this memory is like a Post-it note scribbled on and thrown into a basket with other Post-it notes you have scribbled on that day. When you sleep, your brain takes all these Post-it notes (called “unstable” memories) and puts them in the right order. It’s only after sleep that you can make maximum sense of all that happened.

We’ve all heard that practice makes perfect, but it turns out that the phrase is missing a key element: sleep. Researchers at Harvard found that without the right rest, perfection may be even tougher to attain. Half of the subjects in their study were taught a simple finger-tapping task and were then tested on it and retested later in the day. The other half were taught the same task, but they got to sleep on it before being retested. While the first group realized mild improvement, the second group’s finger-tapping skills showed a 20 percent increase in motor speed over the previous day, without loss of accuracy. Consider the outcome of another study done at Harvard, this one by Ina Djonlagic and her colleagues, which aimed to see how sleep propels our ability to learn. From childhood on, you are constantly categorizing objects and events, which enables you to better manage new material and experiences, both familiar and foreign. In this experiment, undergrads were shown how to categorize a series of cards, tested, and then allowed to sleep that night. The following morning, they were tested again, and their scores improved by 10 percent. Their improvement didn’t come from just studying harder, it came from taking better care of themselves. Our learning is enhanced when we are given time to sleep on it. “Practice and then sleep make perfect” may not be as catchy, but it’s the wiser strategy.

Say it’s one o’clock in the morning and you have a big exam at eight. Should you stay up and cram, or shut down and snooze? Drilling that study sheet without sleep is like Snapchatting the info: one moment it’s there, the next it has disappeared. In one study, students who reported sleeping well performed two grades better than their sleep-deprived peers taught the same information. Another study showed that students with consistent bedtime and wake-up times had an average GPA of over 3.5, whereas the GPA of more irregular sleepers was below 2.7.

Sleep and Your Body

It’s not all in your head—sleep acts as a regulator for the rest of your body: your health, the way you look, and even your weight. If you’ve noticed the relationship between lack of sleep and how often you get a cold, that’s the 50 percent reduction in your immune response talking. And beauty really is more than skin deep. In a Swedish study, subjects between the ages of eighteen and thirty-one were photographed after a night of good sleep, and then again after pulling an all-nighter. The photos were given to a series of untrained observers, who overwhelmingly found that when well rested, the subjects were significantly more attractive.

If you find that you eat more when you haven’t slept enough, it’s not just about a decrease in willpower. The right amount of sleep balances two specific hormones in your body: ghrelin, which is found in your gut and stimulates your appetite, and leptin, found in your fat, which tells your brain you are full. A bad night of sleep leads to a perfect storm: your ghrelin goes up 28 percent (“Hey, [yawn]… let’s get some doughnuts”), while your leptin is down 18 percent (“Wait… just one more!”). If that isn’t bad enough, it turns out that when you don’t get enough sleep, you get a boost in your endocannabinoid levels. Does anything strike you about that word? You got it, getting a bad night of sleep gives you the munchies without having done anything that is (in most states) illegal.

Adding the “How” to “How Much”

Think of a time when you got plenty of shut-eye and still woke up feeling groggy, and you’ll realize that sleep is about both quantity and quality. To build a good night of sleep, you will need to understand the stages that make up your sleep architecture.

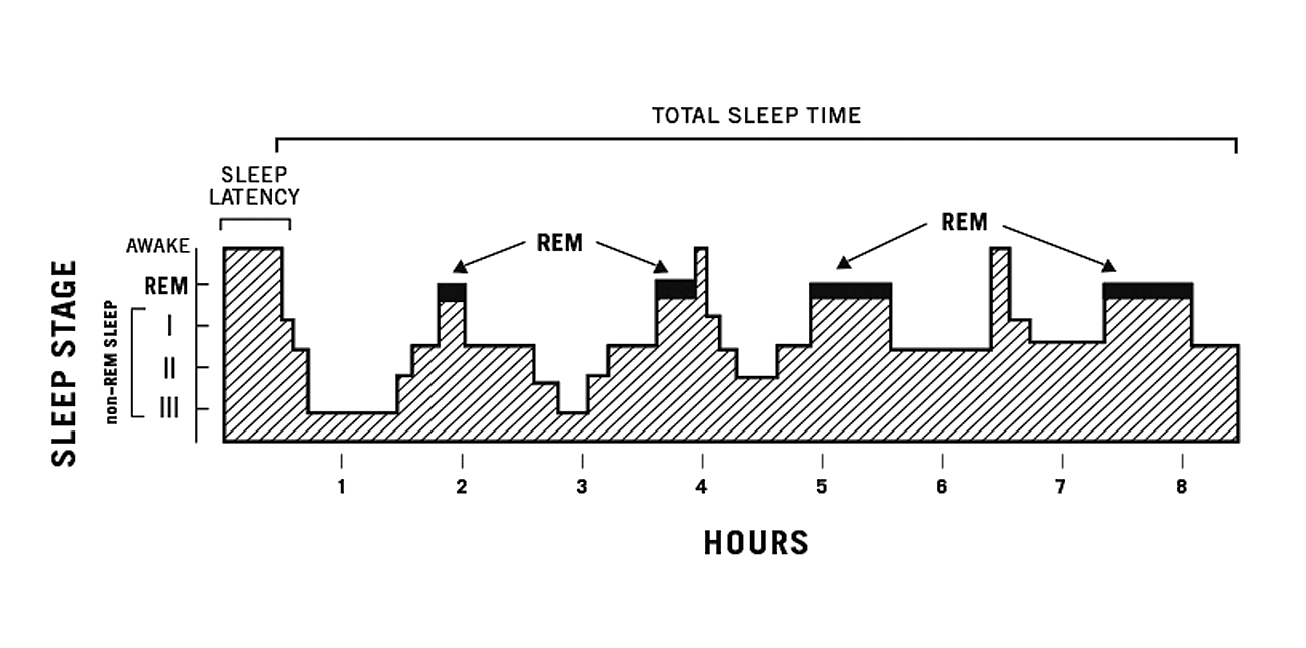

The graph above represents a solid night’s sleep. (We know, we know… eight hours, haha… just come along for the ride.) The moment you shut your eyes, the timer begins. In a fantasy world, when you are well rested, the first stage is a ten-to-fifteen-minute period of “sleep latency,” when your eyes are closed but you haven’t yet begun to snooze. If you are out in less than ten minutes, there is a good chance that your body is overtaxed and craving sleep. If it takes you much longer, there may be issues to be addressed, and we’ll have some answers for that in “Opportunities for Action.”

As you see in the graph, after sleep latency you go into stage I, then stage II, and finally stage III of non-REM sleep: non–rapid eye movement sleep—your body moves but your eyes are still. Each stage is considered progressively deeper and harder from which to wake up. During non-REM sleep, your brain is in fully active mode, when you thread together and encode the facts you’ve learned since you last dozed.

After descending into our deepest sleep, we ascend back to our lightest slumber and then experience REM sleep: rapid eye movement sleep, where your eyes do dart quickly from side to side but the body becomes still. REM sleep is when you dream, as well as when you encode your procedural memory, that is, capture not just what you did, but how you did it. In stage I you might commit to memory the facts you need for the written portion of your driver’s test; in REM sleep you’ll store processes like how to actually drive the car.

Like stage I, REM sleep is very light, and we are more easily woken up and less upset at the intrusion. In the figure here you will notice that our first experience of REM sleep is the shortest, but each successive period gets longer. We can dream up to four times every night, and for brief moments, often unmemorable, we almost come out of sleep. As the night progresses, we get shorter episodes of deep sleep and longer periods of REM sleep, so not getting enough sleep means fewer opportunities to tie things together from the day. This is why trying to catch up on sleep is like trying to turn back time: it’s just not gonna happen. This is also why we can’t “bank” sleep. Getting twelve-plus hours on the weekends may give your body some time to refuel, but all of those later and longer REM opportunities that were missed during the week mean that some stuff is just gone. Memories, learning, buh-bye.

Nap-Happy

Napping during the day is more than a recharge, it’s a supercharge; it’s not just restoring your cognitive powers but giving them a serious boost. Frequent nappers make up 52 percent of high academic performers. A twenty-minute nap between 1 and 3 p.m. may be the equivalent of an hour of nighttime sleep. Our levels of melatonin (a naturally occurring hormone that tells us to sleep) rise twice a day: once in the evening and another slightly smaller burst in the early afternoon. Pay attention to your melatonin and your brain will thank you.

An effective power nap is twenty to thirty minutes long (not including the time it takes to fall asleep). This brings you no deeper than stage II, helping you to avoid deeper sleep, where your brain does not want to be interrupted. If you’re going to take a longer nap, you want to make sure you leave yourself enough time to go down to stage III and come back out of it (90 to 120 minutes), perhaps even making it to your first dream. We hope it’s a sweet one.

Sweet Dreams

You can find out exactly how well you’re managing your zzzs by taking a few minutes to complete the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in the exercises at the end of this chapter. No matter where you lie in the Land of Nod, here is some of the best expert advice to help you get the rest you need.

Larks and owls: Larks thrive by hitting the sack early and waking at the crack of dawn, while owls do their best work well after midnight. During adolescence and into their early twenties, many people naturally become a bit owlish, which is why in 2013 the secretary of education, Arne Duncan, tweeted “start school later.” Whether you’re a lark or an owl, you still need a certain amount of sleep. Create a schedule around your sleep needs—try to avoid early-morning classes if you’re a hard-core owl, for example.

Larks and owls: Larks thrive by hitting the sack early and waking at the crack of dawn, while owls do their best work well after midnight. During adolescence and into their early twenties, many people naturally become a bit owlish, which is why in 2013 the secretary of education, Arne Duncan, tweeted “start school later.” Whether you’re a lark or an owl, you still need a certain amount of sleep. Create a schedule around your sleep needs—try to avoid early-morning classes if you’re a hard-core owl, for example.

Night light: Television screens, computer monitors, the iPad, and even cell phones emit blue light, which decreases melatonin and thus dampens your desire to sleep. This is why you shouldn’t be looking at any screens before bedtime. Content matters, too. If you are watching something particularly gripping, your brain will keep working long after your eyes are closed. If you don’t want to power off, a program like f.lux can decrease the blue light emission (certain televisions and phones can also diminish their blue light). But ideally, you should keep gadgets out of arm’s reach (yes… you can put your phone in the drawer across the room) to minimize temptation and maximize your shut-eye.

Night light: Television screens, computer monitors, the iPad, and even cell phones emit blue light, which decreases melatonin and thus dampens your desire to sleep. This is why you shouldn’t be looking at any screens before bedtime. Content matters, too. If you are watching something particularly gripping, your brain will keep working long after your eyes are closed. If you don’t want to power off, a program like f.lux can decrease the blue light emission (certain televisions and phones can also diminish their blue light). But ideally, you should keep gadgets out of arm’s reach (yes… you can put your phone in the drawer across the room) to minimize temptation and maximize your shut-eye.

Too on to turn off: Occasionally, our bodies are so fatigued or our brains are so overstimulated that they won’t let us drift off to dreamland. When we become too tired, many of us become slightly activated (we feel a bit loopy or, in clinical parlance, hypomanic). We are so tired that we find it difficult to settle down for bed. We do not pay attention to the melatonin signaling the body to go night-night, and it can be hours before we get another chance.

Too on to turn off: Occasionally, our bodies are so fatigued or our brains are so overstimulated that they won’t let us drift off to dreamland. When we become too tired, many of us become slightly activated (we feel a bit loopy or, in clinical parlance, hypomanic). We are so tired that we find it difficult to settle down for bed. We do not pay attention to the melatonin signaling the body to go night-night, and it can be hours before we get another chance.

If you are in bed for more than twenty minutes and can’t fall asleep, get up. Sit in a chair with low light and read a book (ideally, something that would normally help you nod off, perhaps something for class) until you are feeling tired enough to go back to bed and try again. It is helpful to associate your bed with falling asleep, not with the failure to do so.

If you are in bed for more than twenty minutes and can’t fall asleep, get up. Sit in a chair with low light and read a book (ideally, something that would normally help you nod off, perhaps something for class) until you are feeling tired enough to go back to bed and try again. It is helpful to associate your bed with falling asleep, not with the failure to do so.

Drinking yourself awake: Whether it’s Red Bull or coffee, these are called stimulants for a reason, and they keep you on your feet. Caffeine can be essential to staying on your toes—hey, college wouldn’t be college without coffee shops—but with effects lasting anywhere from six to twelve hours, if you hit it too late, you’ll never get to sleep. On the flip side, whether you are among the 10 percent of students who report using alcohol to fall asleep or like to party well into the night, don’t be fooled: alcohol is no friend to sleep, either. It blurs that valuable REM sleep just like it does your vision, “fragmenting” it and wreaking havoc on your sleep cycle. If you ever wondered why you could sleep forever after drinking but still wake up feeling exhausted, bingo!—now you know.

Drinking yourself awake: Whether it’s Red Bull or coffee, these are called stimulants for a reason, and they keep you on your feet. Caffeine can be essential to staying on your toes—hey, college wouldn’t be college without coffee shops—but with effects lasting anywhere from six to twelve hours, if you hit it too late, you’ll never get to sleep. On the flip side, whether you are among the 10 percent of students who report using alcohol to fall asleep or like to party well into the night, don’t be fooled: alcohol is no friend to sleep, either. It blurs that valuable REM sleep just like it does your vision, “fragmenting” it and wreaking havoc on your sleep cycle. If you ever wondered why you could sleep forever after drinking but still wake up feeling exhausted, bingo!—now you know.

Making room for sleep: Trying to sleep in a well-lit room is like trying to study in the dark. Bedrooms that are dark, quiet, and cool set you up for successful and steady nights. If you are a reader, dim the light (forty-watt bulbs are about right for bedside tables). If it’s noisy, go with earplugs. If it’s hot (as in warm… we would never tell you to dismiss the other), cool it down.

Making room for sleep: Trying to sleep in a well-lit room is like trying to study in the dark. Bedrooms that are dark, quiet, and cool set you up for successful and steady nights. If you are a reader, dim the light (forty-watt bulbs are about right for bedside tables). If it’s noisy, go with earplugs. If it’s hot (as in warm… we would never tell you to dismiss the other), cool it down.

A body at rest: Hitting the tranquility button can be tricky at the end of the day. A long, hot shower might seem relaxing, but beware of staying in the steam too long—anything that raises your core temperature will inhibit melatonin. Likewise, exercise can wear you out, but doing it too close to bedtime will also heat you up. Ideally, you shouldn’t exercise within two to three hours of going to bed. There is considerable evidence to support meditation as healthy bedtime prep, so give that a try. Settling in for slumber is like landing a plane: a gradual descent will give you the softest landing.

A body at rest: Hitting the tranquility button can be tricky at the end of the day. A long, hot shower might seem relaxing, but beware of staying in the steam too long—anything that raises your core temperature will inhibit melatonin. Likewise, exercise can wear you out, but doing it too close to bedtime will also heat you up. Ideally, you shouldn’t exercise within two to three hours of going to bed. There is considerable evidence to support meditation as healthy bedtime prep, so give that a try. Settling in for slumber is like landing a plane: a gradual descent will give you the softest landing.

Opportunities for Action

Exercise: Epworth Sleepiness Scale

How sleepy is sleepy, anyway? The Epworth Sleepiness Scale is an objective assessment of whether or not you are getting enough shut-eye. As you imagine the following scenarios, ask yourself how likely you are to doze off or fall asleep right now. Use the following scale to choose the most appropriate number for each situation:

0 = would never doze

1 = slight chance of dozing

2 = moderate chance of dozing

3 = high chance of dozing

Situation/Chance of Dozing

1. Sitting and reading ___

2. Watching TV ___

3. Sitting inactive in a public place (such as a theater or meeting) ___

4. As a passenger in a car without a break ___

5. Lying down to rest in the afternoon ___

6. Sitting and talking to someone ___

7. Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol ___

8. In a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic ___

Add up your score. If your total is:

0–7: It is unlikely that you are abnormally sleepy.

8–9: You have an average amount of daytime sleepiness.

10–15: You may be excessively sleepy.

16–24: You are excessively sleepy and should consider seeking medical attention.

This scale gives you a tool to use, for example, whenever you get into a car, or just to get a sense of whether you should be getting more sleep. If your score is above 16, don’t panic—maybe you just pulled an all-nighter. Remember, when we are tired, we aren’t using our best brain; a little objectivity might go a long way toward making a better decision.

Exercise: To Hack It, Track It

While the majority of college students are at their cognitive best when getting between seven and nine hours of sleep each night, assessing what is right for you is key. This exercise allows you to look at your personal sleep patterns and determine what’s best.

1. Record all the caffeine you consume each day.

2. Write down everything you eat, drink, and smoke within two hours of going to sleep.

3. Write down everything you do during the hour before you go to sleep. Be sure to note the timing of any exercise during that hour, as well as what you watch, read, or do online, and with whom you talk.

4. The next day, record whether and when you woke during the night, for how long, and what you did when that happened.

5. In the morning, note how your previous night’s mood affected your sleep and how you feel on waking up. A good night of sleep should leave you feeling refreshed. Do you try to relax before bed, and if so, how? Does it help?

When you’ve completed a week, you’ll have a rich resource at your disposal. What common themes emerge around both the good nights and the bad? Do certain people or conversations leave you restless before bed? Does it look like you’re guzzling too much coffee? You might notice that you have particularly good nights (and mornings that follow) when you hit the sack with a book in hand or listen to chill music rather than club beats. This exercise can help you get a sense of what’s working for you right now… and what’s not.

The Takeaway

The Big Idea

Sleep doesn’t just return us to baseline, it is a cognitive enhancer and allows us to learn and perform at our best.

Be Sure to Remember

Greater achievement in school isn’t always going to involve more hours in the library—getting seven to nine hours of zzzs can make you smarter, healthier, and even more attractive.

Greater achievement in school isn’t always going to involve more hours in the library—getting seven to nine hours of zzzs can make you smarter, healthier, and even more attractive.

When the afternoon slump hits, a twenty-to-thirty-minute power nap can recharge your brain and solidify what you have already learned that day, and is the equivalent of one hour of nighttime sleep.

When the afternoon slump hits, a twenty-to-thirty-minute power nap can recharge your brain and solidify what you have already learned that day, and is the equivalent of one hour of nighttime sleep.

Consuming caffeine or alcohol or exercising too close to bedtime can negatively impact the quality of your sleep.

Consuming caffeine or alcohol or exercising too close to bedtime can negatively impact the quality of your sleep.

Making It Happen

To understand how to sleep better, we need to examine what we do while we are awake. Keep a sleep journal for one week and we can guarantee that you will get more out of your shut-eye.

To understand how to sleep better, we need to examine what we do while we are awake. Keep a sleep journal for one week and we can guarantee that you will get more out of your shut-eye.

Reading is a fantastic way to help yourself drift off, but if the light is too bright, you might be, too. Dim the light or get a forty-watt bulb and you will find yourself where you want to be: asleep.

Reading is a fantastic way to help yourself drift off, but if the light is too bright, you might be, too. Dim the light or get a forty-watt bulb and you will find yourself where you want to be: asleep.

The blue light emitted by electronic devices cues your body to stay awake. Try downloading the app f.lux, which blocks the blue light emission (comes standard on iPhones at this time as “Night Shift.” Either swipe up from the bottom edge of any screen or go to Settings >Display & Brightness >Night Shift).

The blue light emitted by electronic devices cues your body to stay awake. Try downloading the app f.lux, which blocks the blue light emission (comes standard on iPhones at this time as “Night Shift.” Either swipe up from the bottom edge of any screen or go to Settings >Display & Brightness >Night Shift).