Chapter 7

Joining the Rhythm Nation

IN THIS CHAPTER

Making some notes last longer than others

Making some notes last longer than others

Balancing notes with rests

Balancing notes with rests

Getting a feel for time signatures

Getting a feel for time signatures

Music is more than just a series of long, sustained, droning tones. Sure, this description may apply to a few avant-garde pieces — and that stuff bagpipers play — but you probably want to play some songs with melodies and rhythms that make people want to sing and dance.

In this chapter, I show you just how important the timing of your notes is when playing the piano. As they say, timing is everything, and every note in music has a starting point and an ending point. So notes need to have different values that can be counted. You also see how time in music can be measured in other ways: by measuring the rate of the beat to determine the tempo of a song, and by using a time signature to determine the beat pattern of a song.

You’ll earn your place in the rhythm nation as you get to know the timely trio — tempo indications, note and rest values, and time signatures — that creates rhythm. This chapter introduces you to these rhythm elements and gives you some practice tunes to play on your keyboard.

Eyeing Tempo: The Beat Goes On

The beat is what you tap your foot to; it’s the steady pulse that provides the groove of the music. A fast-paced dance song can get you pumping on the dance floor with a quicker beat, and a slow love song can make you want to sway gently to and fro with your honey in your arms. One of the first things to do when you play music is find out what the tempo is. How fast does the beat go? These sections take a closer look at tempo.

Measuring the beat using tempo

Time in music is measured out in beats. Like heartbeats, musical beats are measured in beats per minute. A certain number of beats occur in music (and in your heart) every minute. If you’re like me, when a doctor tells you how fast your heart is beating, you think “Who cares? I don’t know what those numbers mean.” But when a composer tells you how many musical beats occur in a specific length of musical time, you can’t take such a whimsical attitude — not if you want the music to sound right.

To help you understand beats and how they’re measured, look at a clock or your watch and tap your foot once every second. Hear that? You’re tapping beats — one beat per second. Of course, beats can be faster or slower. Look at the clock again and tap your foot two times for every second.

How fast or how slow you tap these beats is called tempo. For example, when you tap one beat for every second, the tempo is 60 beats per minute because there are 60 seconds in one minute. You’re tapping a slow, steady tempo. When you tap your foot two times per second, you’re tapping a moderately fast march tempo at the rate of 120 beats per minute.

Composers use a tempo indication and sometimes a metronome marking to tell you how fast or slow the beat is. The tempo indication, shown above the treble staff at the beginning of the music, is a word or two that describes the beat in a simple way: fast, slow, moderately fast, and so on. A metronome marking tells you the exact rate of the beat, as measured in beats per minute. Table 7-1 lists tempo indications and their general parameters using common Italian and English directions.

TABLE 7-1 Tempos and Their Approximate Beats Per Minute

Tempo Indication (Italian) |

Translation (English) |

General Parameters of Number of Beats Per Minute |

Largo |

Very slowly (broad) |

|

Adagio |

Slowly |

|

Andante |

Moderately (walking tempo) |

|

Allegro |

Fast, lively |

|

Vivace |

Lively, brisk (faster than allegro) |

|

Presto |

Very fast |

|

Grouping beats in measures

Think of a music staff as a timeline. (Chapter 6 tells you all about the music staff.) In the same way that the face of a clock can be divided into minutes and seconds, the music staff can also be divided into smaller units of time. These smaller units of time help you count the beat and know where you are in the song at all times.

A three-minute song can have 200 separate beats or more. To keep from getting lost in this myriad of beats, it helps to count the beats as you play the piano. But rather than ask you to count up into three-digit numbers and attempt to play at the same time, the composer groups the beats into nice small batches called measures (or bars).

Each measure has a specific number of beats. Most commonly, a measure has four beats. This smaller grouping of four beats is much easier to count: Just think “1, 2, 3, 4,” and then begin again with “1” in each subsequent measure.

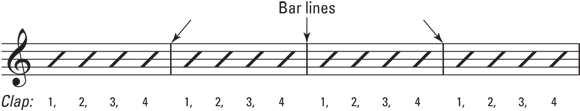

The composer decides how many beats to put in each measure and then marks each measure with a vertical line called a bar line, as shown in Figure 7-1. (See Chapter 6 for more on bar lines.)

Why does it matter how many beats are in each measure? Measures help group beats into patterns. These patterns are made up of downbeats and upbeats, which are beats that are emphasized or de-emphasized, respectively. The repeating beat pattern determines a song’s time signature, which I get into later in this chapter in the section “Counting Out Common Time Signatures.”

Figure 7-1 shows a staff with several measures of beats. The slash marks represent each beat. Clap these beats as you count out loud. The first time you try it, don’t emphasize any of the beats. The next time, emphasize the first beat of each measure a little more than the other three by clapping louder. Notice how this emphasis adds a little pulse to the overall rhythm, creating a beat pattern.

FIGURE 7-1: Bar lines help group the beats. Clap to the rhythm slashes.

Serving Some Musical Pie: Basic Note Values

When you listen to music played on the keyboard, or any other instrument for that matter, you hear notes of different lengths. Some notes sound as long as a fog horn; other notes are quite short, like a bird chirping; and others are of a medium length, like the “moo” of a cow. The melody of a song is defined as much by its rhythm — its combination of long-, short-, and medium-length notes — as by the actual pitches. Melody without rhythm is just a nondescript series of musical tones. Rhythm without melody is, well, a drum solo.

Some songs are so well-known that you can recognize them by their rhythm alone. For example, the holiday favorite “Jingle Bells” has a unique rhythmic pattern. After hearing it in every shopping mall and grocery store from November to January each year, you’d probably recognize the song if someone simply clapped the rhythm of the melody.

Piano music uses lots of different symbols and characters. Perhaps the most important symbols to know are those that tell you the length of each note. The unique order and pattern of note lengths make up a song’s melodic rhythm.

Each note you play lasts for a certain number of beats or a certain fraction of a beat. If math doesn’t exactly thrill you, don’t worry: The fractions you use in music are no more complex than the fractions you use when you carve up a fresh pie.

Picture yourself at the ultimate dessert table, staring at hundreds of freshly baked, meringue-topped pies. Now, pretend that each pie represents one measure of music.

Your master chef (the composer) tells you at the beginning of the dessert (music) how many equal pieces to cut each pie (measure) into. Each resulting piece of pie represents one beat. You can eat the whole piece of pie, or just a part of it, depending on how hungry you are (how the music should sound).

Quarter notes: One piece at a time

Most pieces of music have four beats per measure. In essence, your master chef asks you to cut each pie into four equal pieces. When you divide something into four, you get quarters. When you divide a measure into four parts, you also get quarters — quarter notes.

FIGURE 7-2: Count and play quarter notes.

Try playing the quarter note G’s in Figure 7-2 on your piano, using your right hand, second finger (that’s RH 2). (Chapter 5 tells you about fingering.) Begin by tapping your foot to the beat at a tempo of one tap per second. Count out loud “1, 2, 3, 4.” Each time your foot taps the floor, play the next quarter note on the piano. When you reach the bar line, keep playing, tapping, and counting your way through the remaining measures.

Half notes: Half the pie

Returning to the dessert table, if you cut a pie into quarters and you eat two pieces, you end up eating half the pie. Likewise, if you divide a measure of music into four beats and play a note that lasts for two beats, you can surmise that the two beats equal a half note.

Figure 7-3 shows you four measures with half notes and quarter notes. Notice that a half note looks similar to a quarter note with its rounded note-head and long stem, but the half note’s note-head is open (hollow) instead of closed (filled in).

FIGURE 7-3: Save half for me.

Try playing the notes that you see in Figure 7-3. For every half note, hold the key down for two beats, or two foot taps, before playing the next note. Keep counting “1, 2, 3, 4” to help you know when to play and when to hold.

Whole notes: The whole pie

If you eat all four pieces of a pie that has been cut into four pieces, you eat the whole pie. If you play a note that lasts for all four beats of the measure, you’re playing a whole note.

For obvious oblong reasons that you can see in Figure 7-4, this note is sometimes referred to as a “football.” Like the half note, the whole note’s note-head is hollow, but its shape is slightly different — more oval than round.

FIGURE 7-4: Whole notes hold out for all four counts.

The art of playing whole notes is an easy one — that’s why you may hear someone in a band say, “My part’s easy; all footballs.” Play the notes in Figure 7-4 by holding the key down for four beats, or four foot taps. Keeping the tempo moving along, go across the bar line and immediately play the next measure because a whole note lasts for the whole measure. Remember to count all four beats as you play, which helps you maintain a steady rhythm.

Counting all the pieces

FIGURE 7-5: Mixing up all the notes.

Faster Rhythms, Same Tempo

As the masterpiece in Figure 7-5 shows, just because a measure has four beats in it doesn’t mean that it can only have four notes. Unlike quarter, half, and whole notes (which I talk about in the preceding section), some notes last only a fraction of a beat. The smaller the fraction, the faster the rhythmic motion sounds because you hear more notes for every beat, or foot tap. The following sections examine these faster notes and explain how you can include them in your piano repertoire.

Eighth notes

When you cut the four beats in a measure in half, you get eighth notes. It takes two eighth notes to equal one beat, or one quarter note. Likewise, it takes four eighths to make one half note. And it takes eight … you get the idea.

FIGURE 7-6: Flags on eighth notes become beams.

To play the eighth notes in Figure 7-7, count the beat out loud as “1-and, 2-and, 3-and, 4-and,” and so on. Every time your foot taps down, say a number; when your foot is up, say “and.” When there’s a mix of eighth notes and quarter notes, continue counting all the eighth notes of the measure in order to stay on track.

FIGURE 7-7: Play and count the eighths and quarters.

Sixteenth notes and more

By dividing one quarter note into four separate parts, you get a sixteenth note. Two sixteenth notes equal one eighth note.

As with eighth notes, you can write sixteenth notes in two different ways: with flags or with beams. One sixteenth note alone gets two flags, while grouped sixteenth notes use two beams. Most often you see four sixteenth notes “beamed” together because four sixteenth notes equal one beat. And frequently, you see one eighth note beamed to two sixteenth notes, also because that combination equals one beat. Figure 7-8 shows examples of beamed sixteenth notes plus eighth notes joined to sixteenth notes.

FIGURE 7-8: Sixteen going on sixteen.

To count sixteenth notes, divide the beat by saying “1-e-and-a, 2-e-and-a,” and so on. You say the numbers on a downward tap; the “and” is on an upward tap, and the “e” and “a” are in between. In a measure with a combination of eighths and sixteenths, you should count it all in sixteenth notes.

Sixteenth notes aren’t so difficult to play at a slow ballad tempo, but try pounding out sixteenth notes in a fast song and you sound like Jerry Lee Lewis — and that’s a good thing!

You could divide the beat even more, and some composers do until there’s virtually nothing left of the beat. Figure 7-9 shows that from sixteenth notes you can divide the beat into 32nds, then 64ths, and even 128ths.

FIGURE 7-9: Dividing the beat into oblivion.

Listening for the Sound of Silence: Rests

No matter how much you enjoy something, you can’t do it forever. Most composers know this and allow you places in the music to rest. It may be resting the hands or simply resting the ears, but rest is an inevitable and essential part of every piece of music.

A musical rest is simply a defined period of time in the flow of music when you don’t play or hold a note — you play nothing. When you’re under a rest, you have the right to remain silent. The beat goes on — remember, it’s a constant pulse — but you pause in your playing. The rest can be as short as the length of one sixteenth note or as long as several measures (which is usually the case when you’re playing in some sort of ensemble, and you rest while the others continue playing). However, a rest usually isn’t long enough to order a pizza or do anything else very useful.

For every note length, a corresponding rest exists. And as you may have guessed, for every rest there’s a corresponding symbol. These sections lay it all out for you.

Whole and half rests

When you see a whole note F, you play F and hold it for four beats. For a half note, you play and hold the note for two beats. (The earlier section “Serving Some Musical Pie: Basic Note Values” covers whole and half notes.) A whole rest and half rest ask you to not play anything for the corresponding number of beats.

Figure 7-10 shows both whole and half rests. They look like little hats — one off (whole rest) and one on (half rest). This hat analogy and the rules of etiquette make for a good way to remember these rests. Check it out:

- If you rest for the entire measure (four beats), take off your hat and stay for a while.

- If you rest for only half of the measure (two beats), the hat stays on.

FIGURE 7-10: Hat off for a whole rest, and hat on for a half rest.

These rests always hang in the same positions on both staves, making it easy for you to spot them in the music. A whole rest hangs from the fourth line up, and a half rest sits on the middle line, as shown in Figure 7-11.

FIGURE 7-11: Placement of whole and half rests on the staff.

To see whole and half rests in action, take a peek at Figure 7-12. In the first measure, you play the two A quarter notes (use your third finger) on beats 1 and 2, and then the half rest tells you not to play anything for beats 3 and 4. In the second measure, the whole rest tells you that you’re off duty — you rest for four beats. In the third measure, you put down your donut and play two G quarter notes (second finger) and rest for two beats. Finally, the whole show ends in the fourth measure with a whole note A.

FIGURE 7-12: Practice your whole and half rests.

Quarter rests and more

In addition to whole and half rests (refer to the preceding section), composers use rests to tell you to stop playing for the equivalent of quarter notes, eighth notes, and sixteenth notes. Figure 7-13 shows you the five note values in this chapter and their matching musical squiggles.

FIGURE 7-13: Notes and their equivalent rests.

You might think of the quarter rest as an uncomfortable-looking chair. Because it’s uncomfortable, you don’t rest too long. In fact, you don’t rest any longer than one beat in this chair.

The eighth rest and sixteenth rest are easy to recognize: They have the same number of flags — although slightly different in fashion — as their note counterparts. An eighth note and eighth rest each have one flag. Sixteenth notes and rests have two flags.

Figure 7-14 gives you a chance to count out some quarter and eighth rests. Try clapping the rhythms first, and then play them on your keyboard using the suggested fingering above each note.

You read sixteenth-note rests when you get into more advanced music. Until then, just remember what they look like (refer to Figure 7-13).

FIGURE 7-14: Counting quarter and eighth rests.

Counting Out Common Time Signatures

In music, a time signature tells you the meter of the piece you’re playing. Each measure of music receives a specified number of beats. (See “Eyeing Tempo: The Beat Goes On” earlier in this chapter for more information on beats.) Composers decide the number of beats per measure early on and convey such information with a time signature, or meter.

The two numbers in the time signature tell you how many beats are in each measure of music. In math, the fraction for a quarter is 1/4, so 4/4 means four quarters. Thus, each measure with a time signature of 4/4 has four quarter-note beats; each measure with a 3/4 meter has three quarter-note beats; and each measure of 2/4 time has two quarter-note beats. Figure 7-15 shows you three recognizable tunes that are written in each of these three time signatures. Notice how the syllable count and word emphasis fit the time signature.

FIGURE 7-15: You can recognize the tunes of three common time signatures.

Common time: 4/4 meter

The most common meter in music is 4/4. It’s so common that its other name is common time and the two numbers in the time signature are often replaced by the letter C (see Figure 7-16).

FIGURE 7-16: The letter C is a common way to indicate 4/4 meter.

In 4/4, the stacked numbers tell you that each measure contains four quarter-note beats. So, to count 4/4 meter, each time you tap the beat, you’re tapping the equivalent of one quarter note.

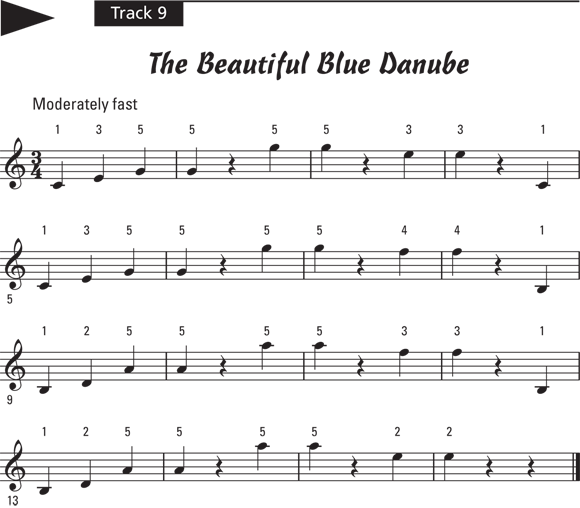

Waltz time: 3/4 meter

In the second most common meter, 3/4, each measure has three quarter-note beats. Of course, this doesn’t mean that only quarter notes exist in this meter. You may have one half note and one quarter note, or you may have six eighth notes, but either way, the combination equals three quarter-note beats.

In 3/4 meter, beat 1 of each measure is the downbeat, and beats 2 and 3 are the upbeats. It’s quite common, though, to hear accents on the second or third beats, like in many country music songs.

March time: 2/4 meter

Chop a 4/4 meter in half and you’re left with only two quarter-note beats per measure. Not to worry, though, because two beats per measure is perfectly acceptable. In fact, you find 2/4 meter in most famous marches. The rhythm is similar to the rhythm of your feet when you march: “left-right, left-right, 1-2, 1-2.” You start and stop marching on the downbeat — beat 1.

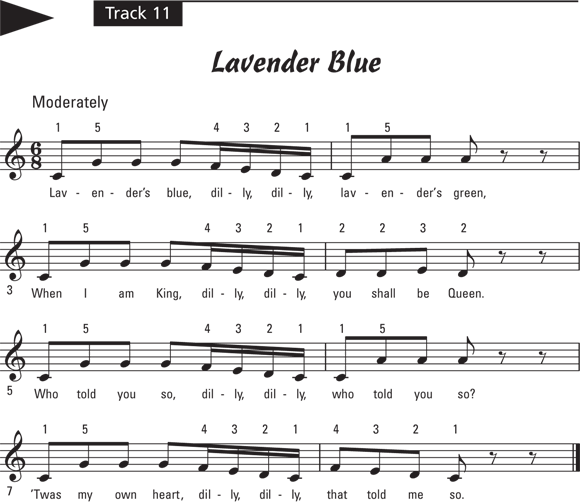

6/8 time

If you notice that a time signature of 6/8 doesn’t have a “4” in the bottom (denominator) position, you’re no doubt already thinking that it can’t be a meter based on quarter notes. If you’re thinking that it might be a meter based on eighth notes, you’re right on time. 6/8 meter is a grouping of six eighth-notes per measure.

Like the waltz, beats in 6/8 meter are grouped in threes, but there are two groups. The 6/8 meter has an added down-up beat pattern on the first eighth note of each group — beats 1 and 4. Showing the emphasis using italics, you count a measure of 6/8 with one count for each eighth-note beat, as follows: One, two, three, four, five, six. Beat 1 is a stronger downbeat than 4, so this beat pattern can feel like two broader beats (down-up), each with its own down-up-up pattern within.

Playing Songs in Familiar Time Signatures

The songs in this section are examples of each of the four time signatures covered in this chapter: 4/4, 3/4, 2/4, and 6/8. These are the most common beat patterns in music. In fact, you won’t find too many popular songs, folk songs, dance tunes, or lullabies that don’t use one of these meters.

You can see that each song has a tempo indication above the starting clef, giving you the chance to feel the beat of the song before you start playing. Use your average walking pace as a guide to a moderate tempo. A fast tempo is the equivalent of walking (or marching) quicker, and you can slow down to an easy saunter to get an idea of a slow tempo. For a tempo indication of “Fast” in 2/4 time, for example, you can start to feel a beat pattern of two beats per measure, one downbeat and one upbeat, at a relatively fast rate. (Refer to Table 7-1 earlier in this chapter for more on tempo indications and their equivalent metronome markings.)

If your skills in reading and playing music on your piano aren’t up to playing these melodies yet, don’t worry — you get some more help in the coming chapters. For now, feel free to tap your foot on the downbeats and clap on the upbeats. The real goal of this chapter is to get you recognizing note values and time signatures.

If you’re ready to give the songs a go, here are some suggestions:

- “A Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight”: The half notes that start the melodic phrase of this song mark the downbeats on 1 and 3. Play along with the audio track, and listen for the upbeats (on 2 and 4) played in the accompaniment part.

- “The Beautiful Blue Danube”: The melody of this classic waltz really takes you out on the dance floor. Notice the rests that are on beat 2 of most measures. Make sure you release the key after playing beat 1 in these measures, so the rest can give you a nice big upbeat on 2.

- “Can Can”: The eighth-note pattern in the melody of this song lets you have fun with the down-up beat pattern. See if you can make a difference between the downbeats and upbeats by giving a bit more emphasis to the eighth notes on the beat and a bit less to those in between (counted as “and”).

- “Lavender Blue”: The rhythm of the lyrics effectively spells out the 6/8 beat pattern in this song. Count the sixteenth notes in 6/8 time: “1-and, 2-and, 3-and, 4-and, 5-and, 6-and.” The sixteenth notes in the first measure are counted, “5-and, 6-and,” matching the lyric, “dil-ly, dil-ly.”

As you learn to read and play music, keep in mind that tempo indications leave a good amount of discretion to the performer and can be followed in ways not limited to the exact rate of the beat.

As you learn to read and play music, keep in mind that tempo indications leave a good amount of discretion to the performer and can be followed in ways not limited to the exact rate of the beat. = 40–60

= 40–60 Get yourself a metronome, a handy little device that clicks out the beats at whatever setting you choose, so you don’t have to spend all day wondering how to calculate 84 beats per minute. You may have seen some older metronome models, with their mesmerizing, pendulum-style clickers. Newer digital models are about the size of a cellphone. And speaking of cellphones, you can also download metronome applications to your cellphone.

Get yourself a metronome, a handy little device that clicks out the beats at whatever setting you choose, so you don’t have to spend all day wondering how to calculate 84 beats per minute. You may have seen some older metronome models, with their mesmerizing, pendulum-style clickers. Newer digital models are about the size of a cellphone. And speaking of cellphones, you can also download metronome applications to your cellphone. After you know how to count, play, and hold the three main note values, try playing

After you know how to count, play, and hold the three main note values, try playing  To play the song “A Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,” skip to the section “

To play the song “A Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,” skip to the section “