Chapter 11

Map Investigative Workflows

Abstract

All suspicious events detected throughout the organization must be reviewed to determine the impact and the potential risk to business operations. In every instance, depending on the level of risk identified, a decision needs to be made for how different incidents will be handled throughout the organization.

Keywords

Escalation; Incident management; Investigative workflow; Roles and responsibilitiesThis chapter discusses the seventh step for implementing a digital forensic readiness program as the need to establish the workflows for handling different types of investigations throughout the organization. Whether an incident has been detected through proactive security monitoring or by human watchfulness, every incident must be assessed to determine how it will be dealt with and who within the organizations needs to be involved.

Introduction

Forensic investigations can be triggered from many different types of events generated by a variety of security controls. Whether they originate as a result of human watchfulness, rule matching in an intrusion prevention system, or modification of data alerted on file integrity monitoring (FIM), organizations must demonstrate an acceptable level of due diligence by ensuring they review each event as they are generated.

While reviewing events, security analysts need to quickly assess the level of risk to the organization and make a decision of whether a full forensic investigation needs to be initiated. The criteria for deciding when an event becomes an investigation should not be simply left to the judgment of the security analyst, a series of policies and procedures must be established to clearly define when this escalation is performed. At the point an investigation is initiated, governance documentation should already be in place and include detailed information for how to proceed and whom to involve.

Incident Management Lifecycle

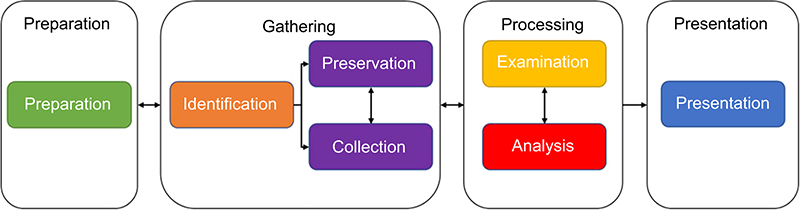

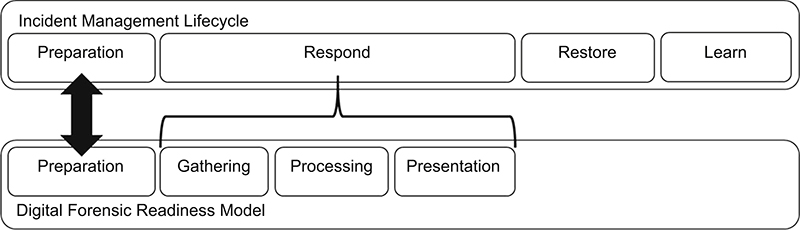

A forensic investigation can be initiated from several types of events or incidents. Similar to how the digital forensic readiness model, as illustrated in Figure 11.1, provides a consistent and repeatable workflow for conducting a forensic investigation, the way in which organizations manage their incidents should also follow a consistent, repeatable, and structured workflow framework.

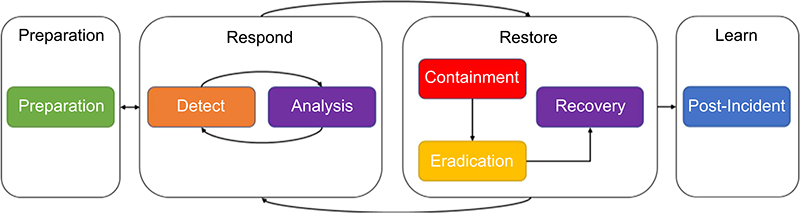

Incident management consists of several phases through which specific activities are performed to mitigate the impact of the incident by containing it and ultimately recovering from it. Illustrated in Figure 11.2, there are four major phases within the incident management lifecycle, each containing a subset of activities and steps that must be performed. Typically, the phases of an incident management lifecycle are completed in sequence and, similar to that of the digital forensic readiness model, may require that preceding phases are revisited as new events or findings are detected, making it very much a lifecycle.

Integrating the Digital Forensic Readiness Model

When an incident has been declared, organizations must consider the implications their actions have on potential digital evidence, with respect to its admissibility in a court of law, as they work through the incident management lifecycle. Illustrated in Figure 11.3, the activities and steps performed during incident response have a direct and collateral effect on the organizations ability to support and conduct a forensic investigation.

Those members of the incident response team (IRT) responsible for performing forensic activities need to have knowledge of the principles, methodologies, procedures, tools, and techniques that apply throughout each phase of the incident management lifecycle. Not only does having this knowledge facilitate more efficient and effective response to incidents, it also ensures that the actions taken during incident handling and response will not interfere with the authenticity and integrity of digital evidence.

Incident Handling and Response

There are four major phases included as part of the incident management lifecycle, including:

• Preparation (initiation)

• Respond (detection and analysis)

• Restore (containment, eradication, and recovery)

• Learn (postincident)

The activities and steps performed in some phases are common to all security incidents, such as when a detected incident has been validated and the IRT moves toward containment actions, while in some incidents there are activities and steps that may not be performed, such as when a detected incident has been invalidated and the IRT moves toward recovery actions. Making effective use of the incident management lifecycle requires that organizations minimize the number of impromptu decisions and subjective judgments being made during an incident. Not only will this facilitate in reducing stress related to potentially making an incorrect decision, but it also provides organizations with a comprehensive methodology that is demonstrably consistent and repeatable when challenged in a court of law.

Phase #1: Preparation

The incident management lifecycle starts by completing activities that ultimately enables the organization to effectively respond and handle incidents. This is the most critical phase of the entire lifecycle because it establishes a foundation for how the subsequent phases will be executed within the capabilities throughout the organizations.

“Event” Versus “Incident”

One of the first actions that should be to taken is specified as part of a taxonomy, discussed further in Appendix F: Building a Taxonomy, what the organizations define as an “event” and “incident.” Doing this as the first step provides a clear scope so that further decisions can be made as to roles and responsibilities, team structures, and escalation workflow criteria.

An “event” is any observable occurrence. Events can be physical or technical in nature such as a user accessing a restricted area or a firewall blocking a connection attempt. Additionally, an “adverse event” is a specific type of event that results in a negative consequence such as system failures, malware execution, or data exfiltration.

An “incident” is any violation or imminent threat of violating the organizations policies, standards, or guidelines. Examples of incidents can be:

• A distributed denial of service attack resulting in system failures

• The release of confidential or sensitive information to unauthorized parties

Policies, Plans, and Procedures

Organizing an effective incident handling and response capabilities requires organizations to establish formal incident management policies, plan, and procedures before an incident occurs.

This series of documentation must emphasize how interactions throughout the organization, as well as with external parties such as law enforcement, will be conducted.

Policies

At the highest level, policies are built as formalized blueprints used to describe the organization goals specific to incident management. These documents address general terms and are not intended to contain the level of detail that are found in the plans and procedures that are created afterward.

While the contents of these documents will be subjective to the organizations individual incident management needs, the following elements are commonly used across all policy implementations:

• Statement of management commitments to incident management

• Purpose and objective for creating the policy

• Scope of whom, how, and when the policy applies

• Inclusion of, or reference to, the organization’s taxonomy which is used to define common terms and language, discussed further in Appendix F: Building a Taxonomy

• Prioritization or severity ranking of incidents

• Escalation and contact information

• Organizational structure including, but not limited to, roles and responsibilities, chain of command,2 and information sharing rules

Plans

Building off of policies, plans are the documents that formally outline the focused and coordinated approach to incident management. It is important that each organization has a plan that is implemented to meet their unique requirements and provides the roadmap for how they will implement their incident response capabilities.

In addition to describing the resources and management support required, this document should also include the following components:

• Mission, strategies, and goals for incident management

• Approach and methodology used to support incident management

• Communication and information sharing plan

• Stakeholder (ie, management) approval of the document

• Service level objectives (SLO)1 used to measure performance

• Roadmap for maturing incident management capabilities

Procedures

Standard operating procedures (SOPs) should be created and maintained based on the organizations implementation of governing policies, plans, and staffing models. Contained within these SOP documents should be comprehensive and detailed technical processes, checklists, and forms that will be used for handling and responding to an incident that align with digital forensics principles, methodologies, and techniques.

The goal for creating these SOP documents is to provide a consistently repeatable process, relevant to all incidents that can be accurately applied to all forensic activities. Suggested components for an SOP document, including the requirements for digital forensics, have been presented throughout the incident handling and response phases in the sections to follow.

Team Structure and Models

An IRT should always be readily available for anybody who identifies or suspects that an event within the organization has occurred. Beyond the availability of incident management documentation, the success of the IRT to analyze events and act appropriately depends on the involvement of key individuals through the organization. Generally, the IRT is responsible for:

• developing appropriate incident management documentation

• retaining resources necessary to perform incident management activities

• investigate the root cause of detected incidents

• manage digital evidence gathered and processed from the incident

• recommend countermeasures and security controls (administrative, technical, or physical)

The way in which an IRT is implemented depends largely on the organization’s size. In business environments where operations are centralized to a smaller geographical region, it is quite effective to have a centralized IRT. However as business environments become more dispersed and operations are scattered across multiple geographical location, there could be a need to deploy regional IRTs. Where there are multiple IRTs distributed across a larger business environment, it is important that all teams are part of a single coordinated unit so that policies, plans, and procedures are consistently used for incident management throughout the organizations.

At the end of the day, the decision to use a centralized or distributed IRT comes down to the cost of deploying the model. Through a cost-benefit analysis, as discussed further in Appendix E: Cost-Benefit Analysis, organizations can determine which team model works best for them.

Roles and Responsibilities

It is important that there is participation of stakeholders throughout the organization to provide their expertise, judgment, and abilities throughout the incident management lifecycle. While the duties performed by each of these stakeholders may not have direct involvement in conducting incident response or handling related activities, their cooperation is essential to ensuring that the policies, plans, and procedures are consistently followed.

Depending on the size of the organization, not all business areas specified in the list might exist. Where this is the case, it is important to identify people who are experienced and knowledgeable in these subject matters so that when an incident occurs there will be no knowledge gap with how to proceed under certain circumstances.

• Management is ultimately accountable for establishing incident management documentation, budgets, and staffing. They are also held responsible for coordinating incident response and handling capabilities among stakeholders and dissemination of information.

• Information security resources provide supplementary support during different stages of the incident response and handling activities, such as validating security controls (ie, firewall rules).

• Information technology (IT) support and administration resources have the most intimate knowledge of the technology they manage on a daily basis. This expertise is important to have when ensuring that appropriate actions are taken for affected assets, such as the proper sequence for shutting down critical systems.

• Forensic practitioners who are knowledgeable in the scientific principles, methodologies, techniques of digital forensics. These individuals must be equipped with proper tools to ensure that incident response activities maintain the forensic viability and admissibility of digital evidence for eventual use in a court of law.

• Legal experts should review all incident management documentation to ensure the organization is compliant with applicable laws, regulations, guidance, and the right to privacy. Furthermore, their expertise should also be sought when it is believed that an incident will have some form of legal ramifications, such as prosecution of perpetrators or the creation of binding agreements for external information sharing.

• Public and corporate affairs will facilitate, depending on the nature and context of the incident, the communication and sharing of information with external parties (ie, media) and the public.

• Human resource and employee relations serve as mediators for disciplinary proceedings where an employee is suspect of being involved with the incident.

• Business continuity planning ensures that all incident management documentation is aligned and consistent with the organizations business continuity practices. During an incident, their expertise can be used to help minimize operational disruptions and assist with communication. Additionally, these people should be made aware of the impact resulting from incidents so they can revise documentation accordingly, such as business impact and risk assessments.

Communication and Escalation

When an incident occurs, those individuals throughout the organization who have an invested interest in the process must be kept readily informed of what is happening. This requires that throughout each phase of the incident management lifecycle, the IRT must ensure they provide adequate and timely information about the incident.

Communication plans should account for the dissemination of information to a wide variety of audiences, across many different delivery channels (ie, in person, e-mail, paper), and be formatted based on the intended audience (ie, other IRTs, management, stakeholders). Not only should information be communicated on a periodic basis (ie, hourly updates, daily summary), but it should also be made available when requested on a “need to know” basis.

Recording and distributing information about an incident should be limited to specific IRT members, sometimes referred to as scribes, whose responsibility is focused solely on communication and escalations. These individuals work closely with other members of the IRT team(s) to document the activities, steps, and progresses through the incident management lifecycle and ensure that accurate and appropriate information is provided to those need it.

External Information Sharing

From time to time, organizations may need to communicate and share information with a variety of external parties such as law enforcement, media, industry experts, and so on. When required, key stakeholders—such as legal, executive management, and public/corporate affairs—should always be consulted prior to the dissemination of any information to external parties. Without having these teams involved to determine how and what level of detail information can be shared, there is a risk that sensitive or confidential information could be disclosed to unauthorized individuals.

Escalation Management

When required, the IRT may need to escalate specific activities about the incident to highlight issues so that appropriate individuals can respond and provide the required level of resolution. Most commonly, escalations are used during incident response to reprioritize, reassign, or monitor specific activities or actions so normal business operations, functions, and services can be restored as quickly as possible. Escalations can typically be grouped into one of the following categories.

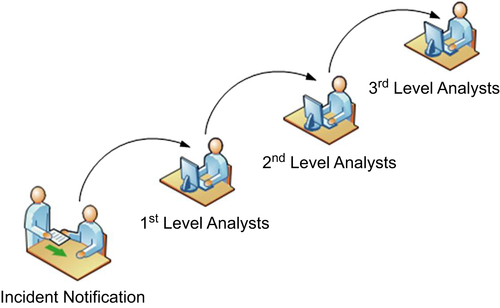

Hierarchical Escalation

Hierarchical escalations are used to ensure that attention is given to the necessary actions for resolving an issue. During a hierarchical escalation, the focus is placed on following the documented chain of command until a resolution is achieved.

Illustrated in Figure 11.4, an example of this can be seen during security monitoring where the first level analysts complete the initial event triage and if they are unable to resolve the issue it is escalated to the second level analysts, and so on until it is resolved.

Functional Escalation

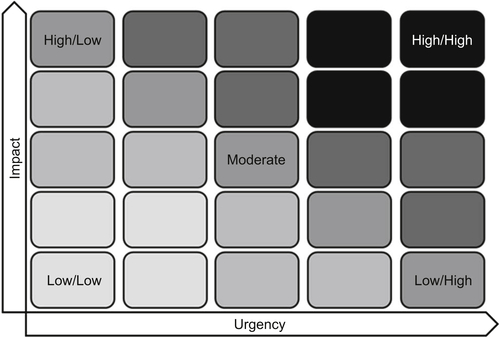

Functional escalations are used to ensure that issue resolution is achieved within a given SLO.1 During a functional escalation, the focus is placed on the priority for resolving the issue as a result of the combined importance and urgency.

Illustrated in Figure 11.5, a priority matrix demonstrates how priority can be determined to resolve issues within a given SLO.

Escalations should not be predominantly used as a means of deviating away from established incident management documentation. This typically happens when an organization incorrectly or vaguely defines when an escalation is to be used during the incident management lifecycle. If this occurs, the IRT will not know under what circumstance they should initiate an escalation, with whom they need to communicate, and how they are to perform the escalation. Examples of when an escalation can be triggered under both categories specified previously include the following:

• Evidence of a reportable crime exists

• Evidence indicates a fraud, theft, or other loss

• Estimate of possible damage exceeds the specified threshold

• Potential for embarrassment or reputational damage exists

• Immediate impact to customers, partners, or profitability is imminent

• Recovery plans have been invoked or are necessary

• Incident is reportable under legal or compliance requirements

Phase #2: Respond

One of the most challenging aspects of the incident management lifecycle is accurately detecting and assessing potential incidents; primarily because incidents can originate from many different attack vectors5 such as the loss or theft of equipment or lack of employee awareness.

While the established SOP documentation supports a consistent and repeatable process for responding to all incidents, the way in which organizations handles each incident varies.

Contained with the scope of this phase, activities and steps performed are focused primarily on the detection and analysis of incidents as they are received.

Detection

Incidents can be detected through many different sources other than the targeted security monitoring capabilities discussed previously in chapter Enable Targeted Monitoring. Regardless, the indicators of an incident can be grouped into one of the following categories:

• Precursor incidents are those events that imply that an incident may occur in the future.

With both categories of events, organizations need to use supplemental information, as discussed further in chapter Determine Collection Requirements, to prevent the impeding incident from escalating and further impacting business operations.

Analysis

Generally, assessing incidents would be relatively simple if precursor and indicator events were guaranteed to always be accurate. However, even when events are confirmed to be accurate, it does not necessarily signify that an incident will or is about to occur. For this reason, it is important that those individual(s) responsible for completing the initial triage determine if the event is true-positive3 or false-positive.4 This validation is an important step in determining what activities and steps will be performed next, such as whether to contain the incident or moved directly into recovery activities.

Where initial validation corroborates that the existence of an incident, the IRT must work quickly to prioritize and understand the context to surrounding the incident. The following techniques are examples of recommended techniques that can effectively reduce the complexity of incident analysis:

• Profiling is the capability to characterize activity so that unknown or abnormal activity can be more easily identified. Examples of profiling techniques that can be used during incident analysis include file integrity monitoring (FIM) (chapter Establish Legal Admissibility) or misuse, anomaly, and specification-based detection (chapter Enable Targeted Monitoring).

• Maintaining information knowledgebase, such as a centralized incident and case management solutions, should be readily available for the IRT to reference quickly during an incident. The knowledgebase should contain a variety of information that can be used to assess an incident including the following:

• Observables are the resulting outputs that might be or have been seen across an organization (eg, service degradation)

• Indicators describe one or more observable patterns that, combined with other relevant and contextual information, represent artifacts and behaviors of interest (eg, file hashes)

• Incidents are distinct instances of indicators that are affecting an organization accompanied by information discovered or decided upon during an investigation

• Adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) describe the attack patterns, tools, exploits, infrastructure, victim targeting, and other methods used by the adversary or attacker

• Exploit targets describe a vulnerabilities, weaknesses, or configurations that might be exploited

• Courses of action are specific countermeasures taken as corrective or preventative response actions to address an exploit target or mitigate the potential impact of an incident

• Threat actors identify and characterize the malicious adversary with intent and observed behaviors that represent a threat to an organization

• Internet search engines can help the IRT to find information about similar incidents or perpetrators. When performing Internet research, it is important to use systems that are not directly associated or connected with the organization so that anonymity can be maintained. Additionally through the use of “throwaway” systems, such as a virtual machine, organizations can avoid the potential of their searches being tracked or correlated by always using a system that operates within a preestablished and known operating state.

Prioritization

Following the analysis and assessment of an incident, the most critical decision to be made by the IRT is establishing the incident priority. As a rule of thumb, incidents that have been assessed should be handled by its priority and not on a first-come-first-serve basis; similar to how a hospital’s emergency room might operate. Prioritizing incidents can be achieved by using the following factors.

Functional Impact

Incidents targeting an organization’s IT assets will most typically have some impact on the organization’s business operations. The IRT should consider not only the immediate negative impact to the business but also the likelihood of future impact if the incident is not contained. The criteria for prioritizing incidents that have a functional impact are illustrated in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1

Functional Impact Prioritization

| Category | Criteria |

| None | No effect to business operations, functions, or services |

| Low | Minimal effect to business operations, functions, or services; no critical services have been impacted |

| Medium | Moderate effect to business operations, functions, or services; a subset of critical services have been impacted |

| High | Significant effect to business operations, functions, or services; all critical services have been impacted |

Informational Impact

Incidents can affect the security properties of an organization’s information, including confidentiality, integrity, availability, authentication, authorizations, and nonrepudiation. The IRT must consider the implications of sensitive or confidential information potentially being exfiltrated as a result of the incident. The criteria for prioritizing incidents that have an informational impact are illustrated in Table 11.2.

Table 11.2

Informational Impact Prioritization

| Category | Criteria |

| None | No information was exfiltrated, lost, or otherwise compromised |

| Privacy breach | Sensitive information was exfiltrated, lost, or otherwise compromised (ie, personally identifiable information) |

| Proprietary breach | Internal information was exfiltrated, lost, or otherwise compromised (ie, architectural diagrams) |

| Integrity breach | Sensitive or proprietary information was exfiltrated, lost, or otherwise compromised (ie, financial records) |

Recoverability Impact

Incidents can result in varying levels of impact to assets and operations. In some instances, it may be possible to quickly recover from an incident; however, in other incidents, additional resources might be required to facilitate the restoration of business assets and operations. The criteria for prioritizing incidents that have recoverability impact are illustrated in Table 11.3.

Table 11.3

Recoverability Impact Prioritization

| Category | Criteria |

| Regular | Restoration time is predictable and can be achieved using existing resources |

| Supplemented | Restoration time is predictable but requires additional resources |

| Extended | Restoration time is unpredictable and requires assistance from existing, additional, and external resources |

| Not recoverable | Restoration time is unpredictable and not realistically possible |

Once the criteria for prioritizing incidents have been established, the IRT needs to ensure that they notify and escalate, if required, to the appropriate stakeholders. Further details about requirements for notification and escalation have been specified in the following sections of this chapter.

Phase #3: Restore

Once an incident has been responded to, appropriate actions must be taken to mitigate further impact and the organization can begin working to recover business operations, functions, and services.

While the established SOP documentation supports a consistent and repeatable process for restoring business operations, functions, and services, the ways in which organizations contain and eradicate each incident can vary.

Contained with the scope of this phase, activities and steps performed are focused primarily on the containment and eradication of incident and subsequent recovery of business operations, functions, and services.

Containment

Before an incident can intensify further, organizations need to determine the appropriate strategies for controlling the impact of the incident beyond the assets and resources it has currently affected. Every incident varies in context, and because of these variations there is no single containment strategy that can be used unanimously. Ultimately, deciding which containment strategy works best for controlling impact beyond the currently affected assets and resources requires organizations to understand the context under which the incident occurred. Examples of criteria that can be used to select an appropriate containment strategy include the following:

• Functional, informational, and recoverability prioritization

• Potential damage to or theft of assets and resources

• Effectiveness of the containment strategy

• Time required to implement the containment strategy

Although the IRT’s primary goal is to select a containment strategy that will assist to eradicate and recover from the incident, careful consideration must be given to the need for preserving potential digital evidence in preparation for legal proceedings. Once the containment strategy has been selected, such as shutting down systems or isolating network segments, the IRT must ensure potential digital evidence is gathered and preserved in the order of the data’s volatility rating.

Generally, the more volatile data within a system the more challenging it is to forensically gather it because it is only available for a specific amount of time. The ability to gather potential digital evidence prior to implementing a containment strategy comes with the inherent risk whereas the longer it takes to make the decision, the greater the risk of the incident intensifying and digital evidence being lost.

When deciding to preserve volatile data, it is important to keep in mind that the more volatile the data, the greater there is a need for knowledgeable individuals and specialized tools to ensure the data is gathered and preserved in a forensically sound manner. Illustrated in Table 11.4 is the order of volatility for digital evidence, ordered from most volatile to least volatile, as discussed further in chapter Understanding Digital Forensics.

Eradication and Recovery

After a containment strategy has been implemented, work can begin to remove the elements of the incident from where it exists throughout the organization. At this time, it is important that all affected assets and resources have been identified and remediated to ensure that when containment measures are removed, the incident does not come back or propagate further through the organization.

Recovery efforts that follow eradication involve restoring assets and resources to their normal and fully functional state, such as changing passwords, restoring data from backups, or installing patches. Recovery should be completed following the eradication of an incident’s impact from a particular asset or resource, not in parallel. By completing these tasks as part of a phased approach, organizations can focus their priority on removing the threats from their environment as quickly as possible, then focusing on the work to keep the organization as secure as possible for the long term.

Table 11.4

| Life Span | Storage Type | Data Type |

| As short as a single clock cycle | CPU storage | Registers |

| Caches | ||

| Video | RAM | |

| Until host is shut down | System storage | RAM |

| Kernel tables | Network connections | |

| Login sessions | ||

| Running processes | ||

| Open files | ||

| Network configurations | ||

| System date/time | ||

| Until overwritten or erased | Nonvolatile data | Paging/swap files |

| Temporary/cache files | ||

| Configuration/log files | ||

| Hibernation files | ||

| Dump files | ||

| Registry | ||

| Account information | ||

| Data files | ||

| Slack space | ||

| Removable media | Floppy disks | |

| Tapes | ||

| Optical disc (read/write only) | ||

| Until physically destroyed | Optical disc (write only) | |

| Outputs | Paper printouts |

Phase #4: Learn

Every incident varies in context and can potentially include a new threat, attack vector, or threat actor that the IRT has not previously accounted for in their incident management program. However, the most commonly overlooked and disregarded phase of the incident management lifecycle involves learning from the incident.

By holding a “lessons learned” meeting with all stakeholders after an incident, the organization can identify additional controls to improve the organizations security posture and enhancing the IRT’s capabilities for future incidents. This meeting is the organizations opportunity to formally close work being done on the incident and begin reviewing specific details about the incident including:

• What happened and at what time(s)?

• How well did stakeholders and the IRT deal with the incident?

• Were incident management processes and procedures followed?

• Did any activities, steps, or actions inhibit restoring business operations, functions, or services?

• How could notification, escalation, and information sharing be improved?

Following the completion of activities in this phase, the incident management lifecycle resets to the preparation phase. When this happens, the outputs from the postincident activities must be carried forward so the incident response process and accompanying documentation can be revised accordingly to reduce the likelihood of new incidents from occurring.

Investigation Workflow

The logical flow from the time when the initial event occurs requires organizations to follow a consistent and repeatable incident handling and response process that encompasses several stages of information gathering (ie, preserving digital evidence, conducting interviewing), communication (ie, stakeholder reporting, escalations), and documentation (ie, SOPs, incident/case management knowledgebase).

The goal of following a logical investigative process, made up of clear and concise workflows, is to reduce the potential for impromptu and uninformed decisions to be made during incident handling and response. However, understanding that the context of every incident is different, the investigative workflow should still provide those involved with the ability to make the best and most educated decision for what actions are performed next.

Before an incident is escalated into an investigation, the IRT should have collected sufficient information to assess the impact of this decision on the organization, including the following:

• Can an investigation proceed at a cost that is proportional to the size of the incident?

• How can an investigation reduce the impact to business operations, functions, and services?

Understanding that each organization is subjective in how they will build their investigative workflow, the diagrams provided in the Templates section of this book can be used as a reference for starting to build a logical investigative workflow process.

Summary

Forensic investigations are most commonly triggered as a result of some type of incident; whether an event was detected through security monitoring, a subpoena was received for legal proceeding, or whether the theft or loss of an asset occurred. Regardless, the logical investigative workflow used to handle and respond to all incidents must be well defined to reduce incorrect decision making but flexible enough to support the variety of incidents as they occur. In any case, organizations must ensure that their governance framework supports consistent and repeatable actions that can be used throughout their entire incident management capabilities.