2

From Stall to Boom

We've Been Here Before

Many of us feel stalled. Growth, both for our companies and for us individually, seems increasingly difficult to attain. There is plenty of evidence of the structural weakening of our economy: stagnant wages, rising debt levels, and anemic productivity growth. It seems the major trends are all working against us: increased global competition, a winner-take-all economy driving massive income inequality, the steady erosion of privacy and security, start-ups worth billions emerging while legacy firms crumble, and technology taking our jobs. It's clear that the old rules of work and business no longer apply.

We (the authors) work with a lot of people excited about the opportunities that lie ahead in the digital economy, but their optimism is often tempered by the news of the day. The headlines all too frequently seem to foretell a pending jobless nightmare of breadlines and robot overlords. And some feel as if there's a party being thrown—in Silicon Valley, New York, and London—that they're not invited to.

Yet within the malaise there is good news. We have weathered similar storms before, and the shape and pattern of our current situation is actually a harbinger for a period of technology-fueled growth. This seems counterintuitive; after all, how can economic stagnation signal future growth and opportunity?

It's because our current stall fits within a well-established pattern that shows up during every major shift in business and technology, when the economy moves from one industrial revolution to the next. In short, we are currently in an economic “stall zone” as the Third Industrial Revolution is (literally) running out of gas, while the Fourth Industrial Revolution—based on the new machine—has yet to grab hold at scale.

This situation creates a dissonance in which we marvel at the computers that surround us, and all they can do, while we search in vain for greater growth prospects for our companies and career security for ourselves.

The good news, which we will explore in this chapter, is that we are coming to the end of the stall zone and entering a time when the economy can break out for those who harness the power of the new machine. We refer to this as the coming “digital build-out,” in which the fruits of digital technology move from Silicon Valley to the entire economy. This value migration will be of a scale similar to the industrial build-out of the last century and will move much faster. To fully understand this transition, it helps to take a look back at the impact of new machines on work in previous periods of tumultuous disruption.

When Machines Do Everything, What Happens to Us?

People have been worried about “new machines” and their effect on the human condition for centuries. Only the machine has changed; the concerns remain the same.

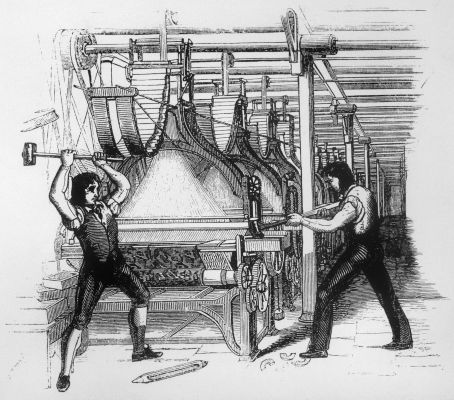

Back in the early 1800s, during the First Industrial Revolution, the Luddites in northwestern England responded to the introduction of power looms by smashing them. They recognized that their textile jobs were at risk. It turned out that they were right; the machines did take over their jobs. Then the same thing happened in agriculture. At the beginning of the 19th century—when the Luddites were smashing looms—80% of the U.S. labor force was working the land. Today, less than 2% of U.S. workers are in agriculture.

When the steam engine enabled mechanization during the Second Industrial Revolution, experts openly worried that “the substitution of machinery for human labor” might “render the population redundant.” 1 As assembly lines made mass production possible, the economist John Maynard Keynes famously warned about widespread unemployment, “due to our discovery of means of economizing the use of labor outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labor.” 2

Today, many of us feel that same sense of trepidation as we read increasingly foreboding accounts of how new machines based on artificial intelligence will displace us. A widely cited Oxford University study estimates that nearly 50% of total U.S. jobs are at risk from the new machines during the next decade or so. 3

But Haven't Our Computers Made Us More Productive?

In spite of this doom and gloom, some of us, being ever-optimistic, will argue, “Maybe so. But all of these computers are having a broad positive effect as they are making all of us more productive.” However, the data doesn't support this argument either.

In spite of the billions spent on enterprise technology (think of all those Cisco routers, SAP applications, Oracle databases, and Microsoft-based PCs, combined with the recent explosion in consumer technologies such as smartphones and apps) worker productivity and associated G7 industrialized nation GDPs haven't budged much. For example, from 1991 through 2012 the average annual increase in real wages was a paltry 1.5% in the UK and 1% in the United States (which was approximately half the level of wage growth from 1970 through 1990), and these were the leaders in wage growth in the industrialized world. 4 Similarly, GDP growth rates in the United States and Western Europe during those two decades were below the GDP growth rates of the previous two decades. 5

How can this be? How is it that we are merely treading economic water in spite of massive technology investments? Isn't this a technology golden age?

Ask yourself: Have your PC, smartphone, e-mail, and instant messaging platforms shortened your work day? Ours neither.

Carlota's Way

The good news amid the gloom is that our current stall zone fits a historical pattern that foretells future growth. Indeed, the signals of fear that the new machine will take our jobs usually appear at the cusp of technology-led economic booms. In fact, if the Fourth Industrial Revolution doesn't generate widespread economic expansion along with associated job growth, we will have broken with history. Why do we have confidence in such a prediction? A Venezuelan-born economist will help guide us.

Carlota Perez is an award-winning economics professor at the London School of Economics. Her most important work focuses on what happens between the end of one era and the beginning of the next. She describes it like this:

History can teach us a lot. Innovation has indeed always been the driver of growth and the main source of increasing productivity and wealth. But every technological revolution has brought two types of prosperity.

The first type is turbulent and exciting like the bubbles of the 1990s and 2000s and like the Roaring Twenties, the railway mania, and the canal mania before. They all ended in a bubble collapse.

Yet, after the recession, there came the second type: the Victorian boom, the Belle Époque, the Post War Golden Age and…the one that we could have ahead now.

Bubble prosperities polarize incomes; Golden Ages tend to reverse the process. 6

Perez describes a coming Golden Age, the digital build-out that's just in front of us. But we're getting ahead of ourselves. How and why can this emerge from our current economic stall? The patterns of history provide us with the guide.

Riding the Waves

When we look back at the invention of the cotton gin, the internal combustion engine, and alternating current, we might sometimes think that one day there was an invention and the next day everything changed. But that's not how the world works. In virtually every case, there was a long and bumpy road connecting one era of business and technology to the next; the evolution of each industrial revolution follows the path of an S-curve (as shown in Figure 2.2 ).

Figure 2.1 Luddites in the early 1800s

Figure 2.2 The S-Curve and the Stall Zone

Why an S-curve? Historically, upon the introduction of new technologies, associated GDP does not rise for decades (the bottom of the S-curve). Select individuals and companies might get rich, but society overall does not. Yet once the technology fully grabs hold, usually 25 to 35 years into the cycle, GDP experiences near-vertical liftoff (the middle of the S-curve). All current members of the G7 nations have experienced this previously—for example, Great Britain rode the steam engine to massive GDP growth in the 19th century, and the United States did the same with the assembly line in the 20th century.

Over time, as the technology is fully adopted and finds its way into most every industry and part of the globe, GDP growth wanes (the top of the S-curve). This is where we are today with the industrial economy of the Third Industrial Revolution. The model of production is well understood, widely distributed, and commoditized. (Consider, for example, the nearly 23 million motorcycles produced in China in 2013.) 7 This top-of-the-curve, flattening-out is what's behind our current economic malaise.

This S-curve pattern of innovation, stall, rapid expansion, then maturity has occurred with the previous three industrial revolutions, and to date it's playing out in the early stages of our computer-driven Fourth Industrial Revolution (as shown in Figure 2.3 .)

Figure 2.3 S-Curves and Industrial Revolutions

Currently we find ourselves at the end of the stall zone and are entering rapid expansion. But this situation of being between stages is also why we have such confusion in today's markets between the optimistic technophiles and the pessimistic economists. Both groups are right if their aperture is focused on the past 20 years (which, for most observers, is often simply based on their own personal experiences). However, in expanding the view over a broader arc of economic history it becomes very clear as to where we are, where we have been, and (most importantly) where we are headed.

To reinforce this point, let's take a closer look at recent history and how these periods fit within Professor Perez's model.

The Burst of Innovation (1980–2000)

The advent of the PC, Steve Jobs's original Mac, Bill Gates becoming the world's richest person, the Internet explosion, the wiring of our corporations. It was all so very heady. It was “the time of the great happiness” as remembered in the technology industry, at least until it all ended in tears with the dot-com bubble and bust.

Similar bursts of innovation have occurred at the beginning of each industrial revolution, paving the way for the great fortunes of titans such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew Carnegie, and John D. Rockefeller. But this wealth was highly concentrated, because the new technologies and their associated business models were understood and implemented by only a few. The public at large would marvel at the new machine of its age; it would garner lots of press and capture the collective imagination, yet its reach was still limited and highly concentrated in a few industries and geographies. Invariably, when too much capital would start chasing too few implementers, financial bubbles would result.

The Stall (2000–2015)

The Internet bubble burst around the turn of the millennium. Then, roughly seven years later, the financial crisis hit. And we've been stalled for a decade and a half. While it all felt new and unpleasantly surprising to us, our recent busts and malaise have also fit closely with the historical pattern.

This stall zone, while painful to experience, is an important period of change. Think of it as the gestation period of a new technology, the larva in the cocoon before it becomes a butterfly, during which the broader economy takes time figuring out how to best leverage the new machine and business models catch up with technology innovation.

This is why the FANG vendors, along with unicorns like Dropbox, Airbnb, and Betterment, are so important; they have provided examples of combining the new machine with new business models. Probably more important is to look beyond the FANG vendors to the industrial leaders that have recognized the shift, such as Siemens, Nike, and Progressive Insurance Corporation. These enterprises are making moves that will take time to come to full fruition but will ultimately set them up for success in the digital build-out phase that will follow the stall. In the coming pages, we will decode many of the important lessons to be learned from both FANGs and well-established corporations who are successful early adopters of new machines and business models.

The Build-Out (2015–2040)

This is the phase when innovations move from the radical fringe to the mainstream. It is the time for the “democratization” of the innovation, as new ideas, which are initially implemented in very concentrated areas, become much more widely disseminated.

This will occur over the next few decades, when industries and institutions that serve as the pillars of our society—banking, insurance, health care, education, transportation, law enforcement, government—leverage the power of the new machine and begin to base their operating models on digital technology.

OK, enough of the economic theory. We took this brief trip through history and economics (summarized in Figure 2.4 ) in order to set the stage for what's happening to all of us currently and to point out that all of the available evidence reveals us to be on a path not to the end of times but to the Fourth Industrial Revolution build-out. Every previous industrial revolution has followed this same basic cycle of innovation bubble, stall, and boom. The digital revolution is no exception, and there are three big reasons for why we are about to transition to widespread, digitally driven growth.

Figure 2.4 The Three Phases of the S-Curve

Three Big Reasons Why a Boom Is About to Occur

As we see it, the transition to the build-out phase will be driven by three parallel large-scale trends:

- “Ubiquitech”—technology embedded into everything . As the Internet of Things (IoT) comes to life, almost everything will become tech-infused, connected, and intelligent. When tech is everywhere, transformation can come from anywhere.

- By 2030 standards, we stink . In 2030, we will look back at many aspects of today's society and wonder, “How did we tolerate that?” We have big problems to solve with the new machine, and in the process massive new forms of demand will be generated.

- Becoming digital—mastering the Three M's (raw Materials, new Machines, and business Models) . Enterprises are “becoming digital,” organizing their people and processes around the capabilities of the new machine. Increasingly, the winning new business models are emerging out of the stall zone, leading to the rearranging of league tables in industry after industry.

Now let's explore all three of these.

“Ubiquitech”—Technology Embedded into Everything

In the next decade, most everything around us will become tech-enabled and connected. The “Internet of Things (IoT)” is the catchall phrase that describes the embedding of computing capability into devices and objects that have previously not had such capacity, and then the connecting of them to the Internet. Think of your shoes, thermostat, or hair dryer; your town's streetlamps and parking meters; and the multiple key components of a jet liner, an assembly line, or a power grid.

In some cases, this digital “enchantment” is relatively limited. 8 For example, a light bulb can now contain a sensor that tells the bulb when it is dark, and thus it turns itself on. In other cases the “thing” is much more sophisticated. An entire house can be wired so that, in effect, it becomes a networked computer—a “smart home.” Not only the lights but also doors, windows, temperature, security features, entertainment systems, and kitchen appliances can all be programmed to do things automatically. Further, they all can be controlled when the home owner is five feet—or 5,000 miles—away from home.

The spread of this capability—making every thing Internet Protocol addressable—is happening at breakneck speed; the scale of the explosion of the “thing” universe is staggering, and even hard to fully comprehend. For example:

- Cisco Systems estimates that the number of connected devices worldwide will rise to 50 billion by 2020. 9 Intel goes even further, suggesting that over 200 billion devices will be connected by then. 10

- McKinsey forecasts that global spending on IoT devices and services could reach $11 trillion by 2025. 11

- With “wearables” constituting an important sub-element of this market, IDC expects global wearable-device shipments to surge from 76.1 million in 2015 to 173.4 million units by 2019. 12

- The smart-home scenario, mentioned above, will be a significant growth area; according to Harbor Research and Postscapes, it generated $79.4 billion in revenue in 2014 when it was just in its infancy. 13 That number is expected to increase to $398 billion as mainstream awareness of smart appliances rises. 14

- The auto industry is becoming “smarter” by the day. Even before cars become fully autonomous (i.e., “driverless”) they will become more like increasingly connected rolling data centers. By 2020, 90% of cars will be online, compared with just 2% in 2012. 15

- General Electric estimates that the “Industrial Internet” market will add between $10 trillion and $15 trillion to global GDP within the next 20 years. 16

Of course, these are all just estimates and should be treated with some degree of cool skepticism. But whatever the actual numbers turn out to be, there is little doubt that the trend lines strikingly point in only one direction. The next generation of smart devices will be hugely significant for nearly every kind of business.

In reality though, we've only scratched the surface of this “smart” wave. We can already see texts and our heart rate on an Apple Watch; sure that's cool, but why can't it do a lot more? Why can't Amazon Alexa manage our whole home? Why can't Nest smart thermostats monitor the house for leaks and other insurance risks? In due course, all of these things will happen, and millions of other similar “smart scenarios” will stop being science fiction and will become, simply, our reality.

But improvements in entertainment and domestic life won't impact the wider economy enough to transition us from stall to boom. What is starting to happen and does have the potential to raise all our boats is the application of IoT ideas to mission-critical parts of the economy, such as health care, transportation, and defense. Such a development has begun to radically change work that matters.

We'll look at many more examples of smart devices in Chapter 8 ; for now, just recognize that soon your default position should be to instrument all of your operations, products, and customer experiences.

By 2030 Standards, We Stink

Just as we tease our parents and grandparents about the outhouse in the back yard, black-and-white television sets, and the cars without seatbelts that were common in their day, our descendants will rib us about how rudimentary and odd our tools still are today. They will look back on us and wonder, “How on earth could they live like that?”

If you have very young children, imagine sitting at dinner with them as teenagers 15 years from now, describing the world they were born into. After their giggles over Justin Bieber, the Kardashians (“What was that all about?”), hipster beards, and hashtags, the conversation may move on to more pedestrian issues. For example, you may describe to them what you had to go through to get your car fixed.

You know the scenario, when you go to the service department of your car dealership: you sit there with a dozen strangers, sipping the stale coffee, watching CNN on a TV that's playing about 10 decibels above comfort level. Your mind starts to wander: “How long will this take? Will I make it back to the office in time? And do I really trust what the mechanic is about to tell me about the extent and cost of the repair?” Ten years from now, your car will self-diagnose exactly what is wrong with it, will give you an estimated cost of the repair, and then will schedule itself for an appointment at the dealership based on your calendar. Then, as your car drives itself out of your office's parking lot to get itself repaired, you will start to think of how much we tolerated, and the opportunity costs that abounded, in our pre-digital era.

In 2030, those 15-year-olds will wonder how we didn't know days in advance that we would be coming down with a cold. That every student at school didn't have a highly pixilated understanding of their personal learning style and a supporting individualized curriculum to maximize their development. That when patients arrived at the emergency room they first had to spend time presenting their insurance card and then sitting in the waiting room instead of having their personal health history, as well as pictures and videos of their injury, sent ahead so a team of well-prepared doctors was awaiting them at the door.

Our current industrial-age inefficiencies may feel terrible now, but anyone with an entrepreneurial bone in their body sees problems and friction as business opportunities to fix these gaps. New machine-based digital solutions such as these—multiplied across all industries—will address myriad societal problems, in the process generating enormous economic value. Rather than presaging the end of the middle class, technology will help drive massive financial expansion.

The key point is this: in thinking about digital solutions and artificial intelligence, we often focus on the impact of the technology on the world that we know. Many critics thus go straight to the “How many jobs will the machine destroy?” question, yet the question is really about “What can this technology improve?” The answer is “a tremendous amount,” for in viewing things from a 2030 perspective, it's clear how much is about to change.

To better understand the scope and scale of this opportunity, Cognizant's Center for the Future of Work, together with economists from Roubini ThoughtLab (a leading independent macroeconomic research firm founded by renowned economist Nouriel Roubini) studied 2,000 companies across the globe to understand the economic impact of the new machine. Our study, conducted in early 2016, focused on several industries that are central to our economy but have yet to become truly digital (i.e., retail, banking, insurance [health and property & casualty] manufacturing, and life sciences), which collectively generate over $60 trillion in revenue today (roughly 40% of world GDP). 17

Respondents reported that approximately 6% of that revenue was currently driven by digital but that the figure will nearly double during the next three years to 11.4%. To put this in perspective, this means the “Republic of Digital,” if it existed as a separate country, will soon be a $6.6 trillion economy, making it the third largest economy in the world behind the United States and China and roughly equal to the economic horsepower of the 2015 economies of Germany, the UK, and Austria, combined. As work that matters becomes more fully digitized, leveraging the new AI machines, huge economic expansion is set to occur.

Becoming Digital: Mastering the Three M's

In looking at the digital economy, the consensus view seems to be that recent start-ups shall inherit the earth. After all, who can stop the momentum of relatively young yet already rich and massive companies like Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Uber? Where does this leave the 100-year-old companies, or even the 40-year-old companies? What about them? Actually, in a very good place…if they move quickly.

In our view, long established companies are extraordinarily well-positioned for the digital build-out. This is because they already have advantages for taking the steps required on the next leg of the journey in delivering digital that matters. They understand their markets, products, and associated regulations better than anybody. And, per the IoT section, they have all the assets to instrument in order to gain proprietary insights into their operations and markets. Still, to get there they must align the Three M's.

The Three M's refer to (raw) materials, (new) machines, and (business) models. Further along we devote individual chapters examining how each of these elements is necessary for winning in the coming digital boom. For now, the key point is that these three elements have to be integrated and aligned to create value. Why? Let's look at how the combination of these three elements has driven every major business and technology shift that's come before.

How the Three M's have historically related to each other is illustrated in Figure 2.6 .

In our current context, the Three M's are:

- Raw materials: the data generated from IoT devices and instrumentation of all people, places, and things.

- New machines: systems of intelligence that combine hardware, AI software, data, and human input to create value aligned to a specific business process or customer experience.

- Business models: commercial models that monetize services and solutions based on systems of intelligence.

Perhaps the best example of aligning the Three M's comes from a company that is well over 100 years old.

Today, many mythologize Henry Ford as having invented the car. He didn't. When Ford launched the Ford Motor Company it was actually his third car company (the first had failed and the second became Cadillac), and he had dozens of competitors in Detroit alone, including Oldsmobile, Packard, and Buick.

What Henry Ford did invent, his great gift, was the alignment of the Three M's of his time, with a primary focus on the third; he created a business model based on the assembly line, which completely changed the price and quality points of the automobile. Aligning the Three M's allowed Ford to mass-produce cars (turning them from a toy for the rich into a necessity for the masses), win his competitive battles, reshape transportation, and reshape society.

In subsequent chapters, we'll discuss how the Three M's will impact your organization and your work in more detail.

New Business Models Take Shape in the Stall Zone

The stall zone is vitally important because materials and machines are understood long before the associated business models can adapt.

The starting point for a truly digital business model, or for the specific business process or customer experience in question, should not be “How do we make it better/faster/cheaper by adding new technology to it?” Instead, the question should be “If digital technologies were available when we designed this process, would we have structured it differently?” The former lens gives you Blockbuster, which put Internet e-commerce on top of a retail chain network. The latter lens yields Netflix, which designed core processes as digital from the ground up.

Figure 2.5 Our Connected World

Figure 2.6 The Three M's in Major Business and Technology Revolutions

General Electric currently stands out as an industrial leader that is undergoing the hard work of reconfiguring itself around the Three M's for the digital economy. Incorporated in 1892, GE is the oldest company listed on the New York Stock Exchange, so you couldn't find a better poster child of an old-school industrial company. It retains its leadership in manufacturing power turbines, jet engines, lighting, and locomotives, but it is currently becoming so much more.

GE CEO Jeff Immelt recognized the need to combine data, systems of intelligence, and new business models to win in the digital industrial economy. He noted, “If you went to bed last night as an industrial company, you're going to wake up this morning as a software and analytics company.” 18

Leaders at GE are taking tactical steps to make the shift to the Fourth Industrial Revolution happen by creating what they refer to as “the world's premier digital industrial company.” In recent years, they have jumped fully into ubiquitech, putting sensors into nearly every “thing” they make to generate the new raw material. GE has invested in building an IoT management platform (Predix), which is the company's system of intelligence. And GE hasn't overlooked new business models. It is now selling insights based on the raw material, opening up entirely new lines of business. In fact, GE now has a software business earning more than $6 billion in revenue, making it one of the world's largest software companies. 19

Another example of a 100-year-old industry realigning itself around the Three M's model, and leveraging the new machine, is education, which certainly is a pillar of society where progress is badly needed, long overdue, and finally coming into focus. We met with Joel Rose, co-founder of New Classrooms Innovation Partners, whose work is a leading indicator of a Three M–aligned future. Rose is trying with new tools, machines, and attitudes to reinvent a hidebound industry and mindset seemingly unchanged since long before many of us were in school.

From Stall to Boom, a Time of Optimism

The three of us have been working at the cutting edge of business and technology for years. If you ask people who know us, we could hardly be accused of being naïve or irrationally exuberant about any specific technology. Even so, we have a sense of optimism based on what we see happening in the market, among our customers, and from our research. Essentially, this is what this book is about: getting you to the prosperity found in the coming digital build-out. The primary thing you need to take away from this chapter is the necessity of (a) understanding the new machine and (b) situating it in the right business model. This is the heart of our thesis, and in the coming chapters we detail (and demystify) each of the Three M's in today's success formula and explain how they must be activated to move ahead.

Figure 2.7 A Typical New Classrooms Learning Environment

But before we get to that we need to address “the elephant” in our book, the great concerns we've mentioned that many have about the impact of AI and automation on jobs.