6

Digital Business Models

Your Five Ways to Beat Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is coming. There are hundreds of start-ups with a lot of brains and money working on various alternatives to traditional banking. The ones you read about most are in the lending business, whereby the firms can lend to individuals and small businesses very quickly and—these entities believe—effectively by using Big Data to enhance credit underwriting. They are very good at reducing the “pain points” in that they can make loans in minutes, which might take banks weeks. We are going to work hard to make our services as seamless and competitive as theirs.

Jamie Dimon, Chairman and CEO, JPMorgan Chase, 2016 Annual Shareholder Letter

Silicon Valley is also coming for your company. Digital disruptors in your industry are armed with the new machine, fueled with data. As we have just outlined in the two preceding chapters, you can do the same and, if you go about it correctly, with even greater success.

That said, harnessing the power of the new machine alone is not enough. The final piece of the puzzle, and the ultimate determinant of your success, is surrounding it with the right business model.

Ten years ago, you had to learn how to compete at “the China price” as globalization mercilessly drove unit costs down. Today, your business needs to take another step-change, learning to compete at “the Google price,” not to mention the “Google speed.” In that pursuit, most industrial business models are currently too slow, too expensive, and too cumbersome. They crumble under their own weight in the face of digital competition.

What do we mean by “business model?” It's the process architecture and supporting organizational model through which your company competes. It's how an insurer processes a claim, a bank determines a car loan, or a retailer manages its supply chain and makes money from doing so. Today, in the vast majority of cases, these core aspects of a business are suddenly archaic.

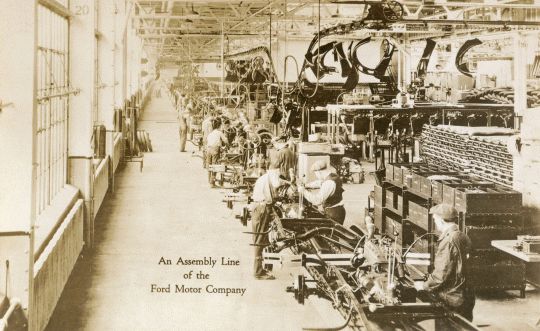

In every well-established company, these business models and supporting processes were formed long before digital technology appeared on the scene. Back then, knowledge work could not be virtualized, aggregated, and instantly distributed to the right people in the right format. (Just think of attempting to create a Facebook equivalent a generation ago without the Internet, smartphones, or relational databases.) As such, knowledge work was structured very similarly to manual labor, and consequently, we're often left with seas of cubicles—in large rooms, in suburban office parks, under fluorescent lights—in which workers push paper to one another. At Ford Motor Company, the accounting staff of the 1930s was structured on the model of the company's River Rouge assembly line (see photos in Figures 6.1 and 6.2 ). The Taylorism that was born in the factory made its way into the office, with the focus primarily on the efficiency and quality of manually processing knowledge work.

Figures 6.1 and 6.2 Knowledge Work and Physical Work Assembly Lines

While such structures all made sense at the time, we will soon look back and wonder, “Why did we do things that way?” Warren Buffett characterized it well in the context of the news business:

If Mr. Gutenberg had come up with the Internet instead of movable type back in the late 15th century and for 400 years we had used the Internet for news and all types of entertainment—and all kinds of everything else—and then I came along one day and said, “I've got this wonderful idea. We are going to chop down some trees up in Canada and ship them to a paper mill—which will cost us a fortune to run through and deliver newsprint—and then we'll ship that down to some newspaper and we'll have a whole bunch of people staying up all night writing up things, and then we'll send a bunch of kids out the next day all over town delivering this thing and we are going to really wipe out the Internet with this”…it ain't going to happen. 1

Of course, such a scenario sounds absurd. Yet you will soon look back on several aspects of your business with the same incredulity that Buffett views the old newspaper business.

That skepticism is already apparent to many of your employees. Millennials, while waiting for an answer to emerge from “cube land,” may often ask, in frustration, “Why can't there just be an app for this?” For a generation that has defaulted to digital, filling out mortgage forms in triplicate seems like utter madness.

In defense of many organizations, though, there are good reasons for long-standing processes to be entrenched and tough to change: quality control, institutional knowledge, fraud management, and regulation, to name a few. And, of course, the daily crush of your operations is enough to deal with—managing the supply chain, dealing with customers, processing orders, managing cash flow—making it easy to defer change for another day. Stability is to be admired, but in the digital economy such considerations can lead to stasis.

With the coming ubiquity of the new machine, however, as we have outlined in the previous chapters, stasis is no longer a viable strategy. Competitors, new and old, will not only be able to change the rules of the game from the outside by delivering vastly improved customer experiences through digital with mobile apps, instrumented products, and advanced analytics for one-to-one customer management. They will also begin changing the basis of competition from the inside, using the new machine to rewire core internal processes. Doing so will fundamentally change their cost base, as well as the speed of their operations and their ability to derive insight on all aspects of the business. Truly better, faster, cheaper. Very simply, in the face of the new machine, manually based knowledge processes do not stand a chance.

With that said, what do you do about it? How do you get your company to move forward? After all, a second great contributor to stasis is too many ideas on how to address the digital threat. We call it being “catatonic by cacophony.” You've probably been in some of these meetings that soon feel like debates. Some may point to digital leaders, advising, “Let's be the Amazon of our space,” while others think, “That sounds inspiring. Yet, I have no idea what it actually means.”

Others argue for starting small by launching a few pilot programs. That sounds reasonable, until somebody in the room says, “Even in the best of conditions, if we extrapolate the growth of those pilots over the next three years, it won't move the needle for us.” Still others may argue, “I'm tired of hearing about digital. That's for other industries, but not ours. Let's just get back to what we've always done best.” Half the room then stares back in incredulity. None of it feels good, but then you go back to your daily operations until the next offsite strategy meeting. So how do you get unstuck?

Hybrid Is the New Black

Let's start by putting the right frame on the issue. Too often, the conversation on “going digital” feels binary: “the industrial firms of the past” vs. “the digital firms of the future.” This is far too simplistic.

With “digital that matters,” the winning business model will be hybrid—part physical, part digital. The airline of the future will still need to get the 280-ton, 300-seat Boeing 787 Dreamliner from New York to London. Yet, much of the passenger experience and flight operations—before, during, and after the flight—will be digitized. Similarly, a hospital will always have its in-person emergency room, operating rooms, intensive care units, and recovery wards, but all will become heavily instrumented and digitized. Some processes will look much the same as they do today, while others will be fully automated and unrecognizable.

As such, your challenge in building a digital business model is different from that of, say, building Twitter. You have an industrial business with existing processes, systems, and culture that has to transition to a blend, a hybrid, with just the right mix of industrial and digital. But what goes where? What stays physical, and what goes digital? And what becomes a mix of physical and digital, and to what degree? For example:

- In looking at your customer channels, what stays with your people (e.g., your sales force, retail stores, etc.) and what goes virtual? Should, for example, a retail bank actively shrink its branch network while transitioning customers to the Web and mobile apps?

- With your product portfolio, which new commercial models should be pursued? Should you begin to reclassify your products as digital services, much like Uber (car as a service), Airbnb (lodging as a service), WeWork (space as a service), Netflix (movies as a service), Nike (personal health management as a service), and GE (industrial uptime as a service)?

- With your process portfolio, where can the new machine drive significant efficiencies? Do you start with core processes or contextual ones? How do you structure such initiatives? Do you create a “newco,” essentially running two companies in parallel—or attempt to transform the current operational process (often referred to as “changing the engines while the plane is in flight”)?

It's all enough to make your hair hurt. This new business model design and implementation can seem daunting. However, best practices are emerging. In our work with over 100 industrial companies looking to make this transition, in addition to our research on thousands of others, the path to business model digitization is becoming clear.

In the remainder of this chapter, we outline the path forward to building the winning hybrid model of the future. All of our work can be distilled into two big pieces of insight from all of these digital transitions:

- Avoiding failure: The four traps to avoid in digital transformation

- Getting AHEAD: The five ways to harness the new machine

Let's start by looking at the primary ways in which digital initiatives go bad.

Avoiding the Four Traps

In working with as many clients as we do on digital transitions, we see that the four biggest traps that even the best-intentioned executives consistently fall into with business model redesign are:

- The “doing digital” vs. “being digital” trap

- The FANG trap

- The “boil-the-ocean” trap

- The denial trap

Let's investigate each of these in more detail.

Trap 1: Taking the Easy Way Out of “Doing Digital” vs. “Being Digital”

Too often we see the superficial use of digital technology, such as putting a mobile front-end on an existing enterprise application that supports an industrial business process. It's quick, it's cheap, it's low risk. But it's also like climbing a tree to get to the moon; you will convince yourself you're making progress toward your digital goal (and, technically, you are), but you will never reach your destination.

We consistently see far too many managers taking fourth-generation machines and jamming them into third-generation business models. Then they wonder why there isn't value being created.

We refer to this phenomenon as “doing digital”—managers simply gluing digital solutions onto industrial business models. Rickard Gustafson, the CEO of Scandinavian AirLines (SAS), framed the problem well:

For us, it's not just about putting some lipstick on a pig and trying to portray a nice portal to the customer. You need to have efficient tools. You need to have an efficient Web offering. You need to have an app. You need to connect to your customers on these mobile platforms, but the key for us is also how do you automate and digitize the inside of SAS. 2

“Digitize the inside of SAS.” Translation? Rethinking, rearchitecting, and rebuilding the supporting business model. Being digital. To gain the truly outsized results that are achievable (and that we outline throughout this book), the supporting business model has to be digital through and through, with process flows and supporting organizational structures based on digital principles instead of industrial ones.

Trap 2: The FANG Trap

Many have attempted to mimic the FANG vendors or the technology company unicorns. Intuitively, it makes sense; after all, they are today's digital masters, and we look to these players with appropriate awe. The problem is not only does this not work, but in several cases we've seen it be highly counterproductive. These firms are from different industries than yours and have different starting and end points.

An assumption contained in the question with which we opened this book (“Will we be Ubered?”) is the notion of “How do we become like Uber?” In the vast majority of cases, that's the wrong question, and in fact, many times it is a dangerous question. More value has now been destroyed than created, costing time, money, and personal reputation, by firms that attempt to become “the Amazon of our space.”

Why? Very simply, it's because the FANG vendors are playing a different game. They (a) are in different industries from yours, (b) had a different starting place, and (c) are targeting a different destination. They built digital businesses from the ground up, creating a purely digital company. Your challenge is different. You need to transition from being an industrial leader into leading as a digital/industrial hybrid organization. Your starting point is different; you have an industrial-era installed base of existing processes, products, and culture. Probably more important, your end goal is different. That's a different challenge from being a digital middleman like Airbnb or creating social media platforms like Facebook or Twitter.

We find blind FANG imitation as being similar to a CFO asking, “What would LeBron James do?” The basketball superstar is absolutely brilliant at breaking down a zone defense during a tense play-off game. However, he probably wouldn't be very helpful to a CFO looking to create, say, a new corporate dividend program. He's playing a different game.

That said, there are a few important areas of the FANG game you need to know cold and that are transferable to your business. They are:

- The new customer expectation: The online experiences provided by the FANG vendors are elegant, simple, and easy to use. They are highly personalized, providing custom content and curated experiences. As such, your product experiences are now being juxtaposed against the FANG expectation. It's why, for example, so many observe, “My $300 smartphone is so smart, and yet my $30,000 car is so dumb.” This gap in expectation and experience will close in the coming years.

- Trust in data: The FANG players have corporate cultures that trust deeply in data. This may seem like a superficial issue, but it's actually profound and central to how a digital company must be run. In industrial companies, there are many different models for decision-making. For example, there's the personality-led culture (e.g., “Why did we make that decision? Because the CEO said so!”). In some circles, this is known as HIPPO culture (i.e., hi ghest p aid p erson's o pinion). Other cultures are deal-led; investment banking and Hollywood come to mind. Still others are process-oriented or regulation-led. While these factors will remain important, in the digital business, all must evolve to first holding faith in the objectivity of data and what it says about products, people, and performance.

- Harnessing the power of the new machine: FANG leaders are all deep believers in and implementers of AI. The CEOs of all these companies have stated, in one way or another, that their companies are “AI first.” Copy that. Send your teams on “digital safaris” to Silicon Valley to, if nothing else, gain insight into the state of the art in operational AI at scale.

Trap 3: Boiling the Ocean

This third point is often the most difficult. We have recognized a best practice of keeping initial projects relatively small. Many highly ambitious management teams decide to go “all in” on digital. They rally the troops, communicate their plans to the board of directors, and confidently declare their intentions inside the company and out (you may still have some of the T-shirts and mouse pads). Then, a year or two down the line, people start asking basic questions: “How is the digital plan going? How has it changed core metrics, like sales or profits? How many customers are now on the platform?” Such questions usually induce highly uncomfortable, staring-at-shoes body language. Although well-intentioned and in many cases very well-resourced, such change initiatives don't work.

Now, this piece of advice is not one-size-fits-all. There are cases in which companies (due to industry structure or competitive moves) find themselves far behind in digital capability. In such cases a “go big or go home” approach may be necessary…for such a high-risk approach is warranted if a company finds itself in a laggard situation. Yet, for the 80%-plus of other companies, we advise to start small.

In starting small, find a subset of a process, one that is simple organizationally, with a straightforward digital technical application, and find quick success. Also, in starting small, build a team of like-minded digital enthusiasts. These team members will be self-selecting. As a best practice, do not try to convince anybody to join your team. If someone voices skepticism or sees the new approach as somehow too risky, move on.

Once this digital SWAT team starts to string a few victories together, momentum will build. Remember the words of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, who during the American Civil War confounded the Union with a string of victories, in spite of inferior resources:

Never fight against heavy odds, if by any possible maneuvering you can hurl your own force on only a part, and that the weakest part, of your enemy and crush it. Such tactics will win every time, and a small army may thus destroy a large one…, and repeated victory will make it invincible. 3

We have found such an approach to digital business model change to be the most effective. Find discrete targets in key processes. Devote the full energies of your best business analysts and technicians to them. Then, with a series of digital successes under its collective belt, the entire organization will begin to gain confidence in the approach. Small changes can have big consequences.

Looking back at the Jamie Dimon quote that opened this chapter, you can see he noted something vitally important in digital business model generation: Digital start-ups “are very good at reducing the ‘pain points’ in that they can make loans in minutes, which might take banks weeks.” “Reducing the pain points” is not “boiling the ocean.” Dimon did not say, “reengineering the entire process”—or the entire organization. Instead, he advises finding the specific pain points that can be relieved and liberated with digital technology.

We surveyed over 300 European and U.S. business leaders to understand how and where they are applying digital tools and techniques to optimize work. As shown in Figure 6.3 , we found that focusing on outdated process bottlenecks and pressure points is, by far, the best practice in helping to create healthier business outcomes and improving work experiences for customers, suppliers, partners, and employees. 4

Figure 6.3 Pervasive Process Potential: Actual Digitization vs. Pilots in Flight

In that study, we found a range of ways in which companies are applying what we call “digital process acupuncture”:

- Insurers are capturing images with drones to reduce insurance underwriting risk and bring them closer to real customer needs.

- Retailers are using digital wallets and beacon technologies to create shopper awareness and boost retail sales.

- Manufacturers are using sensors, the Internet of Things, and RFID for real-time monitoring to streamline the supply chain.

When organizations identify the pressure points and apply digital solutions in very targeted ways, small changes can spark big results. Our research has found that by applying digital tools and techniques, respondents are trimming “fat” to the tune of 8% in cost reductions as well as building digital “muscle” with revenue growth of 10%. In the aggregate, digital process improvements implemented through targeted, narrow steps collectively propelled an 18% net positive for the companies we studied. Spreading this highly focused approach into the rest of the organization is critical, as it:

- Significantly boosts the impact of cost reductions.

- Speeds time-to-market improvements.

- Eliminates friction points.

We also discovered that well over half of all respondents said digital process initiatives have resulted in significant levels of process value chain integration. (We'll give more detailed guidance on where to start this type of work in Chapter 7 .)

Trap 4: The Digital Denial Trap

Digital deniers like to say, “I love what Silicon Valley has provided in my personal life. And, yes, some industries have been hit hard by digital. But we won't be. Our industry is different.” Such thinking is dangerous; those who voice it are in industries that haven't been fully hit by digital yet.

The digital revolution is unevenly distributed. That is, some industries, and their supporting business models (i.e., newspapers, maps, book retailing) have forever been transformed, while others (i.e., energy and utilities) are still relatively untouched.

What accounts for this? There are many factors, including industry structure, nature of the product or service, and regulatory restrictions. However, in our view, the primary factor is the amount of data that is swarming the business.

In nature, elements become unstable with significant changes in temperature and must transform to regain harmony with their environment. Similarly, many businesses have become highly unstable in this era of hyperconnectivity. Just as rising temperatures force change upon matter (with, say, ice turning to water), today's rapid rise of information is forcing structural change upon many corporate models.

Each year in New England, the changes in season turn winter's ice rink into summer's swimming pond. Whether one skates on the ice, swims in the water, or stares up at the clouds, the integrity of the water in any of its forms is never questioned. Water is water, for regardless of its state, it is always two parts hydrogen, one part oxygen. Importantly, we inherently understand the stability of each form given its environment.

There's a strong parallel between the natural states of matter and the proper, or natural, state of an organization. Just as the state of matter naturally changes with increases in temperature, the state of the organization must change with meaningful increases in information (see Figure 6.4 ).

Figure 6.4 Melting Points in Nature and Business

Unfortunately, many managers today are confused. They focus on the state of their organization instead of its substance. For example, management at Borders, Blockbuster, and other retailers defined their organizations as physical retailers that happened to sell books or rent videos, instead of as book and video providers that needed to take on the appropriate form for their market context. Incorrectly conceptualizing the business proved deadly in those markets.

If your industry isn't yet addressing this structural challenge, it's because your sector, like a substance in nature, simply has a different “melting point.” It's why so many managers, yet to be hit by this technology wave, make statements like “That's a music or book thing, but our industry is different.” And yet, the only difference is the industry's melting point. For example, water melts at 32° Fahrenheit, but aluminum melts at 1,221° and tin at just 449°. Just as no substance is immune to heat, no industry structure is immune to today's explosion of information.

Thus far in this chapter we've outlined the four big digital initiative killers. Now let's turn to a more optimistic perspective to highlight the five approaches for building winning digital business models.

Five Ways to Mine Gold from the New Machines

For companies working to get AHEAD, there isn't just one form of business model transformation; there are five. A quick summary of each follows, and as you prepare for the second half of the book (which is much more implementation-oriented and where we go into much more detail about each of these areas), think through which portions of your operations or potential digital initiatives fit into which category.

- Automate: What next level of automation can you apply to an existing human-based process? Can you deploy AI-infused chatbots or kiosks into a service center or registration desk? Can you build an automated process machine that speeds a process in the way that the ATM sped up dispensing cash? If your company is typical, you probably have half a dozen processes ripe for robotic process automation (RPA).In Chapter 7 we describe the rapid shift in which the new machine will begin to manage most, if not all, portions of certain key processes. These will include areas such as claims processing, accounts payable and receivable, legal discovery, service desk incident resolution, network security management, and large portions of customer service and support. In the next five years, this will be the new battleground for cost savings and performance enhancement with the new machine in that the stakes will be high and the economic incentives massive. For example, with initial implementations of RPA, we typically see more than 60% cost savings in the daily operations of a core process, with error rates plummeting to near zero. Although such results will garner many headlines, both good and bad, it will only be the beginning of the automation story.

-

Halo:

What products can you put a digital “halo” around with instrumentation, thus creating new commercial models? What “dumb” objects can become “smart?” What data can you generate that can help you “see” things that were previously invisible, such as the performance of a rotor blade in a turbine?

In our book on Code Halos, we outlined that any noun—any person, place, or thing—had a digital self and a physical self, and we predicted that by 2020, any product costing more than $5 that you couldn't eat would be instrumented. 5 Well, Marc Andreessen has taken that further by predicting that in 20 years, every physical item will have a chip implanted in it. 6 Thus, as a default, you should start thinking about instrumenting all the key products and machines in your business model, and putting a halo around them all. In Chapter 8 we explain how to create commercial value from such efforts.

- Enhance: Which human efforts can be enhanced by the new machine, driving new levels of employee productivity and customer satisfaction? In Chapter 9 , we outline how the machine becomes the new “colleague” of your front-line workers, enhancing their efforts and helping your company reach entirely new performance thresholds.

- Abundance: How can you leverage the new machine to drive down the price point of your products or services to be able to compete and win in low-cost, high-volume markets—markets of abundance? With the new machine, which of your products or services could be sold for 10 times less? Not 5% less, but 90% less. This may sound like madness, a prescription to destroy your revenues. However, what if it led to a new abundance, to markets that might be 100 times the size of your current market? In Chapter 10 we provide tactics for identifying your own abundance markets.

- Discovery: What areas of true invention are now available to you? How much of your focus and budget is devoted to initiatives that won't pay off this year but have enormous potential in the years ahead? If it's infinitesimal, you likely have a future relevancy issue. In 1910, as the Model T gained popularity, few could have envisioned the new markets to be discovered. Who could have predicted suburbia, the big-box retailer (e.g., Walmart), fast food (e.g., McDonald's), and national hotel chains (e.g., Holiday Inn)? Yet, these were all inventions that were derived from the initial invention of the mass-produced automobile.What new discoveries reside in your company? And, importantly, how can you leverage the new machine to revolutionize your R&D process? In Chapter 11 , we outline the new process for invention.

Those that are successful in their digital initiatives tend to be very clear-headed about their goal. They balance each of these five value levers; be it the automation of a business process, boosting the value of an existing product by harnessing the data that surrounds it, enhancing human activities with digital tools, enabling mass-market consumption of your market offerings, or creating an entirely new offering with technology-based invention. They then utilize the right teams, methods, and budgets to pursue that goal. Each of these end-states requires its own path for digital reinvention, and all associated energies need to be focused on that goal. There is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all model, and firms that naïvely follow such an approach quickly encounter trouble.

The Management Opportunity of a Generation

We see many industrial-model leaders investing heavily to become hybrid winners. This book is filled with lessons of these hybrids under construction: GE, Philips, McGraw-Hill, Nike, Under Armour, Toyota. In looking at the statements of intent from their CEOs, a pattern quickly emerges:

- “It's absurd that you know more about your car than you know about your body.…[Under Armour Connected Fitness will] fundamentally affect global health.” Kevin Plank, CEO, Under Armour 7

- “If we are to ensure that healthcare remains affordable and widely available for future generations, we need to radically rethink how we provide and manage it…and apply the technology that can help achieve these changes.” Frans van Houten, CEO, Royal Philips 8

- “Industrial companies are in the information business whether they want to be or not.…Now, add to that a series of decisions every company needs to make: ‘Do I outsource all of that? Do I do it myself? Do I change my business model accordingly?' The decision we've made [at General Electric] is that we just want to be all in.” Jeff Immelt, CEO, General Electric 9

- “Toyota Connected will help free our customers from the tyranny of technology. It will make lives easier and help us to return to our humanity. From telematics services that learn from your habits and preferences, to use-based insurance pricing models that respond to actual driving patterns, to connected vehicle networks that can share road condition and traffic information, our goal is to deliver services that make lives easier.” Zack Hicks, CEO, Toyota Connected 10

- “You know, when I first joined the company, a long time ago, we were a manufacturing company. As we go forward, I want us to be known as a manufacturing, a technology, and an information company. Because as our vehicles become a part of the Internet of Things, and as consumers choose to share their data with us, we want to be able to use that data to help make their lives better. And also, create some business models that will help us earn a return. That's where we're heading.” Mark Fields, CEO, Ford Motor Co. 11

“Radically rethink.” “Fundamentally affect.” “Help us return to our humanity.” “We just want to be all in.” These are words spoken by CEOs who are doing the hard work to rewire their companies for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, to define and implement the new business models.

This is the management challenge of a generation. Let's now explore how to successfully take action against it.