Demographic and Employment Patterns

Beate Josephi, Folker Hanusch, Martin Oller Alonso, Ivor Shapiro, Kenneth Andresen, Arnold de Beer, Abit Hoxha, Sonia Virgínia Moreira, Kevin Rafter, Terje Skjerdal, Sergio Splendore, and Edson C. Tandoc, Jr.

As a foundation for the analyses of crucial variables in the chapters that follow, this chapter provides a comparative profile of journalists in the sixty-seven countries of the second wave (2012–2016) of the Worlds of Journalism Study. It provides answers to a fundamental question—who are the journalists?—in terms of gender, age, level of experience, education, work environment, and employment conditions. Demographic and job-related profiles of journalists are essential basics, but in a comparative examination they are additionally important because they may provide explanations that allow us to grasp the similarities and differences of media environments around the world. By combining data on a range of demographic and employment-related variables, we establish a picture of journalists and their work conditions in newsrooms worldwide.

These conditions shine an important light, for example, on who works in journalism. One recurrent aspect that has been much discussed in journalism scholarship relates to the role of women in the news, with the percentage of women and the length of time they stay in journalism varying across the globe. Belarusian investigative journalist Svetlana Alexievich, the first journalist to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, for example, writes about working for “almost forty years going from person to person, from voice to voice,” recording and capturing the lives of her compatriots (https://

Given the small number of global studies, and therefore the lack of a worldwide overview of journalists, a comprehensive profile that may also explain the relationships between demographic and employment patterns becomes considerably important. It provides benchmarks for future studies, but, more significant, it adds invaluable information to the journalism studies literature given its comparison of journalists’ profiles across a large number of countries. Published in 1998, The Global Journalist for the first time drew together information on journalists from twenty-one countries and territories (Weaver 1998a). The update, The Global Journalist in the 21st Century, included thirty-three countries and regions (Weaver and Willnat 2012). The first wave of the WJS covered twenty-one nations (Hanitzsch et al. 2011). While all three of these provided some information on trends in gender distribution, age, and education, the level of representativeness of the samples varied.

Thus this study, we believe—based on the particular care to approximate the highest level of representativeness outlined in chapter 3—offers the most comprehensive picture to date of journalists across the globe. Half the journalists surveyed work in print. The average age of all journalists is 38 years, and the participation rate of women in the profession is 43 percent. Journalists are increasingly university educated, and on average they stay twelve years in the profession. Less than half of the global journalistic workforce are members of a professional association, and 80 percent are in full-time employment. As this chapter outlines, however, we find considerable variance across the globe in relation to these variables.

Backgrounds and Working Conditions of Journalists

In relation to journalists’ backgrounds and work conditions, journalism scholarship has tended to focus on a range of key aspects, including gender, age, education, and newsroom composition. Most visible has been the concern with gender, particularly in terms of the numeric presence of women in journalism as well as the distribution of power within newsrooms. Global organizations and projects have gathered information on these aspects of journalists’ life and work. The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) has been collecting data on gender and journalism for some time (see, for example, Wage Indicator Global Report 2012). Also, since 1995 the Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP) has provided data every five years on the representation of women in the news media, in terms of both their presence in newsrooms and their representation in news content (GMMP 2015). The UNESCO report Inside the News (2015) has similarly addressed the challenges for women journalists in Asia and the Pacific. Finally, a large body of scholarship is available on the role of women in journalism (see, for example, Allan, Branston, and Carter 2002; De Bruin 2000; Robinson 2005; Rush, Oukrop, and Sarikakis 2005).

Typically these studies have found that women tend to be underrepresented in countries like the United States (Weaver et al. 2007) and—more generally—operating in a male-dominated environment (North 2009). Women also often leave the journalism profession early, a phenomenon that has been attributed to early burn-out syndrome (Reinardy 2009) or to structural inequalities and family-work tensions (Tsui and Lee 2012). In a study of South Korean journalism, Kyung-Hee Kim (2006) outlined the entrenched patriarchal culture, which keeps women’s participation in South Korean journalism at below 25 percent.

The age of journalists has received much less attention, even though it could be an important factor affecting how journalists think about their work. Scott Reinardy (2016) found that journalists in their twenties and sixties experienced greater job satisfaction than did midcareer journalists. In their longitudinal study of American journalists, Weaver and others (2007) used age and work experience profiles as indicators of the state of the labor market. These attributes continue to be used in a similar way as indicators, particularly in North America, Europe, and Oceania, where media companies are transitioning their delivery of journalistic content to digital platforms. The resulting transformations in the companies’ income and work structures have created hiring delays or led to layoffs, which can affect the age profile of journalists. As scholars have argued recently, the increasing precariousness of labor conditions and the ongoing job cuts in traditional newsrooms are deleterious to journalistic work and morale (Gollmitzer 2014; Reinardy 2016; Sherwood and O’Donnell 2018).

As far as journalism education and training are concerned, the literature emphasizes the benefit of well-schooled journalists, especially in the areas of general knowledge, writing, and ethics. In fact, on a global level, scholars have noted a considerable growth in journalism education, tied to attempts to professionalize journalism (Mellado et al. 2013). As a result, journalism scholarship has examined a range of aspects related to the tertiary training of future journalists (e.g., Deuze 2006b; Goodman and Steyn 2017; Hovden, Nygren, and Zilliacus-Tikkanaen 2016; Josephi 2010; Reese and Cohen 2000). Of importance in a comparative context is that pathways into journalism differ across countries, emphasizing either academic or nonacademic traditions (Fröhlich and Holtz-Bacha 2003).

The relationship between various aspects of journalists’ backgrounds and their organizational loci has also been explored for some time. Stephanie Craft and Wayne Wanta (2004) found that female editors tend to encourage positive news reporting and are less likely than men to differentiate between male and female reporters when assigning beats. Paula Lobo and colleagues (2017, 1148) found that both organizational factors and “the traditional gender system” played important roles in Portuguese journalists’ attitudes toward and perceptions about the role of gender in their work. Tracy Lucht (2016) highlighted differences in the issues male and female journalists considered salient and in how they talked about their work, with men more likely to use language that evoked professional efficacy and presence and women more likely to emphasize production and position. Edward Kian and Marie Hardin (2009) found that journalists’ gender influenced how female athletes were presented in the news, with male writers more likely to reinforce gender stereotypes.

Given the considerable literature on how the various demographics and work-related conditions of journalists relate to and interact with one another and transform the institution of journalism, as well as the need for global benchmarks for these variables, this chapter presents a profile of journalists in the WJS both in the form of descriptors and as mutually and iteratively interacting variables that define the conditions of journalism in sixty-seven countries.

Measures

The demographic data collected on journalists included their gender, year of birth, education, and educational specialization as well as the number of years they had worked as journalists. For education, journalists were asked to indicate their level of completion from among the following choices: not completed high school, completed high school, college/bachelor’s degree or equivalent, master’s degree or equivalent, doctorate, or undertook some university studies but did not earn a degree. All those who had attended university were asked whether they had specialized in journalism or another communication field.

In relation to employment patterns, journalists were asked to identify their job titles and their position in the editorial hierarchy; their position was subsequently categorized as rank-and-file journalist (on the lowest level of the editorial hierarchy, consisting of journalists with limited authority, such as reporters and news writers), junior manager (those on the middle level who make operational decisions on a regular basis, such as desk heads, department heads, and senior editors), or senior or executive manager (those with power to shape strategic goals of their news organizations across broad divisions of the newsroom, such as editors-in-chief and managing editors). Journalists’ employment situation was also assessed in terms of full-time, part-time, or freelance work. An optional question identified whether full-time and part-time respondents had permanent or temporary employment. Data were also gathered on whether respondents had any other paid jobs outside journalism, as well as whether they belonged to any organizations or associations that were primarily for people in the journalism or communications field.

Further, the questionnaire measured the medium in which journalists worked (daily or weekly newspaper, magazine, television, radio, news agency, standalone online outlet, or online version of an offline outlet), and whether they worked on various news topics or on a topic in which they had specialized. If they did specialize, they were asked to indicate this in terms of their beat. Beats were coded into three categories: hard news (politics, economy and current affairs, crime and law), mixed (local and regional news), or soft news (society and religion, science, technology, education, environment and health, culture and entertainment, lifestyle, and sports). In this chapter we focus only on the three categories of beats and not on specific topics within the beats.

For a global overview, all central tendencies reported in this and other chapters were averaged across societies. This procedure gives equal weight to every country included in this analysis regardless of population and sample size.

The Global View

The analysis across the sixty-seven countries in our study shows that about 43 percent of all journalists in the study were female (table 4.1). This result was not unexpected given prior evidence that women are underrepresented in journalism (GMMP 2015; Weaver and Willnat 2012). Still, it signifies an advance when compared with the figure of around 33 percent reported in Weaver’s (1998b) first global survey. The mean age of our journalists was 38 years; the median, 36. Nearly two-thirds of journalists were between 24 and 42 years old. Journalists’ average work experience was thirteen years, with a median of eleven years, indicating that most journalists enter the profession when they are relatively young.

Globally, journalists tended to be well-educated, with more than 80 percent holding a university degree. This constitutes a distinct increase over Weaver’s (1998b) finding, roughly two decades before the WJS, that 63 percent of journalists in the twenty-one countries and territories in his study held a degree. It is similar, however, to the result of a more recent study by Weaver and Willnat (2012), which recorded 82 percent. In our study, 89 percent of journalists between the ages of 24 and 40 held a university degree, compared with 83 percent of journalists aged 41 and over. These figures indicate a trend toward a university-educated journalistic workforce across the world.

Despite the overwhelming percentage of journalists who held a tertiary degree, not all of them studied journalism or a related communications field. This is in line with findings from earlier studies that journalism education is not the only and sometimes not even the most dominant pathway into the profession (Weaver 1998b). Still, nearly two-thirds of university graduates in our study specialized in these fields. Out of our global sample—regardless of whether they had studied at university or not—this means that more than 60 percent of journalists had studied journalism or communication at the university level. Younger journalists were more likely to have specialized in journalism at the university level. Of those aged 24 to 40, 60 percent had studied specifically journalism, compared with only 54 percent of those aged 41 and over. This provides yet more evidence of the global trend among journalists to pursue tertiary journalism education (Goodman and Steyn 2017; Mellado et al. 2013).

Table 4.1 Key demographics of journalists across sixty-seven countries

|

Female journalists |

Male journalists |

All journalists |

||||

|

Gender |

43.4% |

56.6% |

100.0% |

|||

|

Age |

||||||

|

Weighted mean a |

35.42 |

39.30 |

37.70 |

|||

|

Average median |

33.85 |

38.27 |

36.18 |

|||

|

Experience |

||||||

|

Weighted meanb |

10.73 |

13.84 |

12.56 |

|||

|

Average median |

9.06 |

12.32 |

10.74 |

|||

|

Educationc |

||||||

|

Completed high school |

11.4% |

17.2% |

14.4% |

|||

|

College/bachelor’s degree or equivalent |

56.8% |

54.1% |

55.5% |

|||

|

Master’s degree or equivalent |

29.9% |

25.6% |

27.5% |

|||

|

Doctorate |

1.3% |

1.9% |

1.7% |

|||

|

Specialized in journalism/communication at universityd |

66.5% |

57.2% |

61.4% |

|||

|

Specializations |

||||||

|

Generalist(e) |

62.2% |

61.6% |

61.7% |

|||

|

Hard news beatf |

22.1% |

23.4% |

22.8% |

|||

|

Soft news beatg |

14.9% |

14.3% |

14.7% |

|||

|

Membership in a professional associationh |

45.2% |

48.5% |

47.2% |

|||

|

Ranki |

||||||

|

Senior/executive manager |

13.0% |

18.2% |

15.9% |

|||

|

Junior manager |

25.8% |

28.5% |

27.2% |

|||

|

Rank-and-file |

61.8% |

53.3% |

56.9% |

|||

|

Employmentj |

||||||

|

Full-time |

78.3% |

81.9% |

80.3% |

|||

|

Part-time |

11.1% |

8.3% |

9.6% |

|||

|

Freelancer |

9.0% |

8.6% |

8.8% |

|||

|

Other paid jobsk |

21.5% |

24.2% |

23.0% |

|||

|

Platform |

||||||

|

|

48.7% |

50.1% |

49.8% |

|||

|

Television |

23.1% |

22.3% |

22.6% |

|||

|

Radio |

17.8% |

16.7% |

17.1% |

|||

|

Online |

14.9% |

16.5% |

15.6% |

|||

|

Note: All percentages, mean scores, and median scores averaged across countries; gender differences significant for items as noted below. a t = −25.36, df = 24,036, p < .001, d = 0.320. b t = −22.63, df = 23,177, p < .001, d = 0.294. c Chi2 = 232.86, df = 4, p < .001, V = .094. d Chi2 = 362.79, df = 1, p < .001, Phi = .119. e Chi2 = 10.31, df = 1, p < .01, Phi = .020. f Chi2 = 40.27, df = 1, p < .001, Phi = .040. g Chi2 = 8.74, df = 1, p < .01, Phi = .018. h Chi2 = 33.71, df = 1, p < .001, Phi = .036. i Chi2 = 205.51, df = 2, p < .001, V = .089. j Chi2 = 99.57, df = 3, p < .001, V = .061. k Chi2 = 7.70, df = 1, p < .01, Phi = .017. |

||||||

An overwhelming majority of journalists—just over eight out of ten—in our sample worked in full-time employment, with the remainder split between part-time employment and freelancing. Further, nearly one in four journalists had a second paid job outside journalism. Not surprisingly, employment outside journalism was particularly widespread among freelancers, almost half of whom did not derive their income solely from journalism. A notable percentage of part-time journalists—39 percent—had a second paid job outside journalism, compared with only 19 percent of full-time journalists.

Just under half of our study’s journalists were union members. We do not have comparative figures from either Weaver’s (1998a) or Weaver and Willnat’s (2012) volumes because only some countries provided these data in both cases. However, from data on union membership recorded in a few studies, it appears that union membership has been declining around the world. In Australia, it dropped from 86 percent in 1998 (Weaver 1998b) to 56 percent in 2010 (Josephi and Richards 2010) and again to 48 percent in 2014 in our study. In the United Kingdom, it dropped from 62 percent in 1998 to 44 percent in our study, and in Spain from 61 percent to 41 percent for the same time span.

On the global level, most respondents in our study—57 percent—were rank-and-file journalists, followed by junior managers and senior or executive managers in that order (table 4.1). Not surprisingly, there was a clear association between journalists’ rank in the editorial hierarchy and work experience. While average work experience for senior managers was eighteen years, it was only ten years for rank-and-file journalists. Similarly, senior managers were on average 44 years old, while rank-and-file journalists were about nine years younger.

Despite the rise of digital media, it appears that journalism is still a predominantly print-based occupation across the globe. In our sample, 35 percent of the journalists worked for a daily newspaper, 9 percent for a weekly newspaper, and 7 percent for a magazine. Another 23 percent worked for a television station, while slightly fewer (17 percent) worked for a radio station. Only 4 percent worked for a news agency, and 16 percent worked for an online outlet.

Finally, with regard to specialization in particular beats, such as politics, sports, and lifestyle, the majority of our journalists identified themselves as generalists, with six out of ten not specializing in a specific area of coverage (table 4.1). Just under one-quarter of all journalists worked in predominantly hard news beats, while 15 percent worked in soft news beats. Journalists specializing in soft news also appeared to face more precarious job situations; more than 84 percent of hard news journalists were in full-time employment compared with 76 percent of soft news journalists.

Among demographics, gender has frequently been discussed as a critical indicator of difference in other dimensions of news work. Indeed, our study found considerable evidence that this is the case on a global level. The findings indicate differences by gender for journalists’ age, work experience, education, specialization, unionization, hierarchies, and employment conditions. Broadly speaking, this is a story of disparity. Across all sixty-seven countries combined, female journalists were on average four years younger and had three years less work experience than men. They were less likely to be members of a professional association in journalism and much less likely to be senior or junior managers than their male counterparts. While women represented 43 percent of all journalists, they represented only 38 percent of all junior and senior managers. They were also slightly less likely to be in full-time employment, that is, more of them were employed part-time and as freelancers, although slightly fewer had another paid job outside of journalism. Further, female journalists were less likely than male journalists to work on hard news beats, and somewhat more likely to work on soft news. More female journalists held a university degree, and more had specialized in journalism while at university. At the same time, the effect sizes reported in the notes to table 4.1 suggest that, if placed in the broader context of news work, gender is a relatively small factor in accounting for variance in most of these aspects.

Gender Differences Across Regions

While the global picture provides a rough indication of key findings, it also masks some considerable differences across individual countries (table 4.2). For example, while overall, women made up 43 percent of journalists in the sixty-seven countries, the country-wise range was large. Women constituted less than one quarter of the workforce in Bangladesh, Japan, and Indonesia but were a two-thirds majority in Latvia, Bulgaria, and Russia (fig. 4.1). The findings are similar for the percentage of women among junior and senior managers. Fewer than 15 percent of managers in Japan, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia were women, while more than 60 percent of women journalists held this position in Latvia, Bulgaria, and South Africa.

Closer analysis of these results shows a strong association with societal factors relating to the role of women, as measured by the Gender Development Index (GDI). A gender-sensitive extension of the Human Development Index (HDI), the GDI accounts for the human development impact of existing gender gaps in the three dimensions of the HDI: life expectancy, education, and income (Klasen 2006; UNDP 2014). The GDI shows the HDI of women as a percentage of the HDI of men and thus acts as a measure of the gender gap in a country. While the GDI has its own conceptual, methodological, and empirical problems, measures of gender development and empowerment have proven useful in previous analyses of gender in journalism (Hanitzsch and Hanusch 2012). Indeed, our comparison of gender balance across sixty-seven countries found strong correlations between the GDI and both the percentage of women journalists in a society (r = .503, p < .001) and the percentage of women managers (r = .509, p < .001, N = 66; fig. 4.2).

Table 4.2 Country overview of sample properties (sociodemographic variables)

Figure 4.1 Women journalists around the world (percentages)

Source: WJS; N = 67.

The most significant clusters of similar percentages of women journalists appear in Europe, with states that have emerged from the former USSR, from former Yugoslavia, as well as those in Eastern Europe characterized by high percentages of women journalists. Across the region, women were in a clear majority, representing more than 60 percent of the total journalistic workforce in Latvia, Russia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Moldova, and more than 50 percent in Estonia, Croatia, Serbia, and Albania. China, the only currently communist country in the survey, had an even gender balance. Kim (2006) suggests that both Marxist and socialist feminism emphasize work as materially changing a woman’s life situation. As the figures for the postcommunist societies in Eastern Europe show, this situation appears to have had a considerable impact on women’s participation in the journalistic workforce. However, it should be recognized that the cataclysmic political events that occurred in that region also had much influence, introducing a young, mostly female workforce into journalism (Lukina and Vartanova 2017). Notably, the high percentage of women journalists also results in high-profile work. One of “journalism’s heroic figures” (Hartley 2000, 40) is Russian investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya; another is the documentary journalist Svetlana Alexievich, referenced earlier (Hartsock 2015). The first female television newsreader in Europe read the news in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) in 1963 (MDR 2013), ten years before a female newsreader appeared on screen in West Germany.

Figure 4.2 Women journalists and gender development

Source: United Nations Development Programme, WJS; N = 67.

Scandinavian countries, too, have a strong tradition in equity in terms of gender distribution in upper-level positions. Eastern and Nordic Europe are reported to have “crossed the one-third Rubicon” with women in the media occupying 33 and 43 percent in top management and governance jobs, respectively, in Eastern Europe, and 36 and 37 percent, respectively, in Nordic Europe (UNESCO 2015, 6). This figure compares favorably with a worldwide trend of less than 10 percent of women in a managerial position across different occupations.

Western Europe, with few exceptions, has a female participation rate in journalism ranging between 40 and 47 percent, showing a clear upward trend compared to the figures found by Weaver (1998). While numbers vary slightly across studies, the United States, on the other hand, has had “a near stagnation growth over the past 25 years,” as a result of which women constitute only about one-third of the journalistic workforce (GMMP 2015, 45; Weaver and Willnat 2012; Weaver et al. 2007).

In South Korea, female journalists made up a quarter of the journalistic workforce. According to Kim (2006), this low participation is likely a consequence of the patriarchal Korean society. Female presence was even lower in Japan. Two countries in South Asia also showed notable low or meager percentages of women journalists: India had 28 percent and Bangladesh 11 percent. This is unlikely to be due to religious reasons as these two countries follow different belief systems. In fact, no distinct pattern emerged for the influence of religion across our sample. For example, in Malaysia, where Islam is practiced by around 60 percent of the population, 50 percent of the journalists were female; this percentage is comparable to the ones found in countries where the majority practice a different religion, such as Scandinavia. In Malaysia, the gender pay gap is smallest among the Asian and Pacific nations (UNESCO 2015).

Malaysia also belongs to a distinct group of Commonwealth countries that have achieved numerical gender equity among journalists. While the United Kingdom is nearing gender balance, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Malaysia, and Singapore already have a predominantly female workforce. A mixed picture, however, emerges for Africa, where all surveyed countries except Ethiopia are former British colonies or protectorates. The East African states of Kenya and Tanzania showed strong rates of female participation in the journalistic workforce, while some of the other African nations scored below 40 percent, and others even below 30 percent.

In Latin America, Brazil stands out with near gender equity, very likely a consequence of a former requirement of a tertiary degree to be licensed as a journalist but also due to the high number of female journalism students. Other South American countries, except Chile, record a substantially lower involvement of women in the media, possibly due to the patriarchal nature of the societies in the region (Oller Alonso and Chavero 2016). In Mexico, in particular, only one-third of journalists were female; this may partially be the consequence of the lack of safety for journalists in this country (Hughes et al. 2017a).

Overall, the past fifteen to twenty years have seen an increase of about 10 percent in women journalists worldwide. However, the conditions of female participation in the profession of journalism do not compare well with the conditions in the labor force in general (Global Gender Gap Report 2016). A number of studies have found that more women enter the journalistic profession than men, but more women than men leave in their thirties. Weaver et al.’s (2007) longitudinal study of American journalists shows this trend most pronounced for 2002. While among journalists under 25, 61 percent were women, among the 35- to 44-year olds, the figure dropped to 25 percent; the figure did go back up to about a third of the workforce among journalists 55 years and older (Weaver et al. 2007). One likely reason for the increase in female journalists globally is the fact that many more women than men have studied journalism since the 1990s (Weaver et al. 2007). Another reason may be the notion—at least in some contexts—that it is the decreasing financial attractiveness of journalism that has led to the increase in women journalists (Lukina and Vartanova 2017).

Age and Professional Experience

Weaver and Willnat (2012), in their study of thirty-three countries and regions, reported that the average age of their sample journalists was 39 years. In the sixty-seven countries of the WJS, the average age of journalists was 38 years, with a median of 36 years. The age of journalists has been considered an indication of employment patterns. Weaver et al. (2007) observed for the United States that many journalists hired during the boom period of the 1970s were still working in 2002. The authors attributed the rising median age of journalists to virtually no growth in the field of traditional mainstream journalism in the 1990s and since. In fact, our results point to a rise in the median age of journalists from 41 years in 2002 reported by Weaver et al. (2007) to 49 years in 2013, when our survey was conducted in the United States. This increase in age in the United States shows that contractions and growth in the job market can have a noticeable impact on the age pattern in the profession. It is also worth noting that journalists’ median age in the United States was considerably higher than the median age of 42 found in the general U.S. labor force more broadly (ILO 2017). Overall, however, journalists’ median ages showed a strong correlation with the median ages of their countries’ labor forces (r = .520, p < .001, N = 65; see fig. 4.3).

In addition to the United States, in a small number of other countries, journalists’ median age was higher than that of the general labor force. These countries include Sweden, where journalists’ median age was more than ten years higher than that of the labor force, as well as the Netherlands, where the difference was just over five years. On the other hand, in a substantial number of countries, journalists’ median age was at least five years younger than the median age of the labor force. These include the former Eastern bloc member countries of Moldova, Romania, Russia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, and countries and territories in Asia, including Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, China, Bhutan, Thailand, and Indonesia. The group also includes the Latin American countries of Chile, El Salvador, Ecuador, and Colombia.

Given the global age patterns, differences go beyond a direct relationship between age and labor market. For example, we found that the maturity of a country’s media sector and the age of journalists were related. More specifically, age and a country’s level of newspaper circulation were related (WAN-IFRA 2014) for the thirty-eight countries in our sample where such data were available (r = .496, p < .001). Countries with an early development of mass-circulation newspapers (Hallin and Mancini, 2004) and a broad readership as measured by newspaper circulation (WAN-IFRA 2014) in the second half of the twentieth century tend to have older journalists. Conversely, countries where the media market developed only in the second half of the twentieth century or where the media sector has considerably grown in past decades tend to have younger journalists. Despite significant media transformations in the twenty-first century, the impact of an early establishment of the media is still evident in the age profile of journalists.

Table 4.3 Country overview of sample properties (employment conditions and working patterns)

Figure 4.3 Median age of journalists and overall labor force

Source: International Labour Organization, WJS; N = 66.

Journalists were younger also in countries where a politically cataclysmic event has led to a renewal of the journalistic workforce. Russia, Romania, and Kosovo, where the median age of journalists was below 30, are examples; these countries underwent considerable changes in their media markets following the collapse of communism and the break-up of Yugoslavia, respectively (table 4.2).

The picture of the relationship between age and experience differs noticeably from the one for age and gender. As noted, countries with long-established media tend to have older journalists, who tend to be men. However, there was no clear opposite pattern. While some countries with a high percentage of female journalists, such as Russia and Romania, have a young workforce, no distinct pattern of female journalists being younger can be established more broadly.

Almost all the older journalistic cohorts are found in North America and Western Europe, where journalists had overall the highest average median age of 44 years. In these countries, journalists also had the most experience, with a median of seventeen years. In the Mediterranean countries, which are characterized by a later development of the press, journalists were five years younger in terms of their median age (39 years). Correspondingly, they possessed less experience, with an average median of thirteen years and a range of medians between fifteen years for Italy and Spain and nine years for France (table 4.2). Arguably, the late development of the media sector due to years of military dictatorship in some Mediterranean countries, and the subsequent new expansion of the job market, had a determining effect on the age of the journalistic workforce.

Africa, overall, had a young journalistic workforce with an average median age of 31 years. Not surprising, then, the professional experience of journalists was quite brief in most African countries, with a low average median of six years. Several countries—Malawi, Kenya, and Sierra Leone—had a median of five years for professional experience. Journalists in Latin America could also be considered young, with an average median age of 33 years, and average median experience of eight years. The differences between countries are considerable, with a median of twelve years of experience for Argentinian journalists, and of only five years for Chilean journalists. The Middle East also presents as a cluster, with an average median age of 37 years and average median work experience of eleven years. In this cluster, Israel had the oldest journalist population, at a level similar to Western liberal democracies. In Egypt, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates, journalists’ average age was very similar to that found in the Mediterranean countries.

The picture in Asia was considerably varied for age and work experience. A cluster emerged only for Southeast Asia. The average median age was 35 years, with a range from 37 years in the Philippines to 33 years in Malaysia and Indonesia. The most experienced journalists were in Japan and the Philippines. In many countries in Asia, journalists were young and did not stay long in the job. The lowest median years of professional experience were found in Thailand and Hong Kong, at four years. In Hong Kong, Celia Tsui and Francis Lee (2012) found that many journalists left after only a few years in the profession. The median years of professional experience in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and China were not much higher, ranging from only six to eight years. The South Asian countries of India and Bangladesh both had a median of nine years in this respect.

As we contended earlier, the history of a country’s press has a lasting impact on the age structure of the journalistic workforce. The media situation in the countries of the Commonwealth is a case in point. Ireland, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand were the dominions and India the colony that took part in the Empire Press Union meeting in 1909. The average median age of 39 years and median work experience of thirteen years in this cluster of countries provides support for the argument that a press fostered early continues to influence the configuration of a country’s journalism institution.

Geographical and historically shaped clusters are discernible for the average age of journalists. With the projected growth of journalism particularly in Asia, it can be assumed that the average age of journalists there will drop because a younger workforce will populate the profession. On the other hand, the trend in the United States and Europe, where the market is contracting, is toward an older workforce, as a comparison with Weaver (1998b) and Weaver and Willnat (2012) shows. Countries whose media are in a growth phase have a younger workforce. Journalists in the BRICS countries had an average median age of 33 and average median work experience of nine years. These states can be taken as representative of the relationship between journalists’ age and a growth spurt in the market. China, India, and Brazil are among the seven most prominent newspaper markets; in 2015 China and India alone accounted for 62 percent of the average global daily print circulation (WAN-IFRA 2016).

Journalists’ age and years of professional experience are also a reflection of employment conditions. In North America, Oceania, and Europe, where relatively high salaries and labor laws had helped build a lifelong commitment to journalism, journalists are now forced to leave the industry because of increasingly precarious financial situations of media organizations. A survey of 225 Australian journalists who had been made redundant between 2012 and 2014 found that 68 percent had worked in journalism for more than twenty-one years (Sherwood and O’Donnell 2018). Also, young cohorts are not the result only of recent media development or growth spurts. They can also be a manifestation of a lingering dissatisfaction with working in journalism and with its pay scales, leading to a “revolving door” syndrome. Hong Kong, with a median of four years of professional experience, is a prime example of a “high degree of turnover within the journalistic profession” (Chan, Lee, and So 2012, 26).

In other parts of the world, low pay and fragility of the job market can prompt journalists not to stay in the job for long. In Chile, where journalists’ “average income is very low” (Mellado 2012, 389), journalists were also young (median of 30 years), and their years of professional experience were few (median of five years). Europe, and in particular postcommunist countries, such as Romania and Moldova, is not immune to this phenomenon; the countries here struggle to find economic stability. In Romania and Moldova, median professional experience was five years. Poor working conditions and poor pay were also present in Kenya (median experience of five years), where journalists are often tempted by “illegal incentives to survive” (Ogong’a 2010, 149); the circumstances often force these journalists to accept such illegal incentives as bribes to make ends meet. In Thailand, where median professional experience was four years, “many reporters did not regard journalism as a long-term career, but as a chance to broaden their experience before going on to further study” (McCargo 2000, 55). Other scholars have similarly indicated that journalism is often considered a transitional phase in young people’s working lives in East Asia (Heuvel and Dennis 1993).

Education and Professional Specializations

The differences among countries in the percentage of journalists who held a tertiary degree appear to be mostly due to the numerous pathways to becoming a journalist. Some European countries have had a tradition of traineeships or nonacademic courses at highly selective journalism schools; these are not considered tertiary education (Fröhlich and Holtz-Bacha 2003; Deuze 2006b). As a result, the nations that stand out as having an unexpectedly low percentage of degree holders (below 70 percent) include Austria, Iceland, Switzerland, and Sweden, which all belong to a group of countries where “a formal journalism education is not required to become a journalist” (Bonfadelli et al. 2012, 325). We also see some evidence of this in Germany, where three-quarters of the journalists held a tertiary degree, but only just over one-third had specialized in journalism or communication (table 4.2). Only one country in the survey, Sierra Leone, provides no easy access to colleges or universities, resulting in only four of ten journalists having completed a degree. University education appears to be widespread in China, Cyprus, Tanzania, India, South Korea, Bhutan, and Japan, where at least 99 percent of journalists held a degree. In another eighteen countries, at least 90 percent of journalists had been educated at university. Overall, we found considerable variance across countries in terms of the percentages of university-educated journalists who had actually specialized in journalism. Less than 50 percent of journalists had specialized in journalism in eighteen countries, which include such diverse societies as Colombia, Germany, Iceland, Indonesia, and South Korea. At the same time, specialization can be quite high in some countries; for example, 93 percent of the journalists in Kenya had specialized. At the other end, in Japan only 12 percent had specialized.

An analysis of the gap between the percentage of university graduates and the percentage of those who specialized in journalism does tell us something about the dominant pathways into journalism across the globe. The results somewhat reflect the categorizations developed earlier by Romy Fröhlich and Christina Holtz-Bacha (2003) and Mark Deuze (2006b), which relate to systems that focus predominantly on university education, stand-alone journalism schools, or vocational on-the-job training. We found the most substantial gap in Japan and Bhutan, where 99 percent of journalists held a degree but only 12 and 23 percent, respectively, had specialized in journalism or communication. This indicates a system where journalism education continues to be primarily conducted in the workplace (Josephi 2017; Kim 1976). In the United Kingdom, where until recently on-the-job training had been the dominant form of education in journalism, we found that only four out of ten journalists had studied journalism at university, despite the fact that, overall, 86 percent were university graduates. Specializing in journalism appears to be very popular in countries like Brazil, Spain, Chile, Kenya, Malawi, Denmark, El Salvador, Cyprus, and Botswana, where at least 80 percent of journalists focused on journalism or communication in their studies.

Whether journalists are assigned to a particular area of coverage also varied considerably across countries. Journalism seems to be the least compartmentalized into beats in Tanzania, where nine out of ten respondents said they worked across a range of topics and issues. Other countries with a high percentage of generalized work include Croatia, Bangladesh, and Malawi. Specialization appears to be much more common in South Korea, Qatar, Sudan, and Israel, where at least 60 percent worked on a specific beat. Some European countries—Netherlands, Austria, Germany, Sweden, Greece, and the UK—also had more than 50 percent of their journalists work on a beat. By far the largest numbers of journalists specializing in hard news were in South Korea and Qatar, where more than half of journalists worked in this area. Only three other countries (Hong Kong, Egypt, and Sudan) had percentages over 40 percent (table 4.2).

Soft news, that is, beats that focus on audiences as consumers, is significantly more likely to be practiced in advanced economies, with at least one-quarter of journalists working on soft news in the Netherlands, Germany, the UK, Belgium, and Austria. In Bhutan, Tanzania, Japan, Mexico, and Bangladesh, however, less than 4 percent of journalists reported working on such news. The correlation between gross national income and the percentage of journalists specializing in soft news is significant and very strong (r = .445, p < .001, N = 66), suggesting that the more economically developed a society is, the more likely its media will focus on soft news, such as lifestyle or entertainment. This relationship is consistent with recent arguments in the literature that point to broader societal trends toward economic security as a reason for the rise in lifestyle journalism. For example, Folker Hanusch and Thomas Hanitzsch (2013) have argued that in many postindustrial societies, where economic resources are secure, people have more options and flexibility to shape their lifestyles, in line with the move from survival values to self-expression values (Inglehart 1997). This change in values, they argue, contributes to a rise in lifestyle coverage in the news.

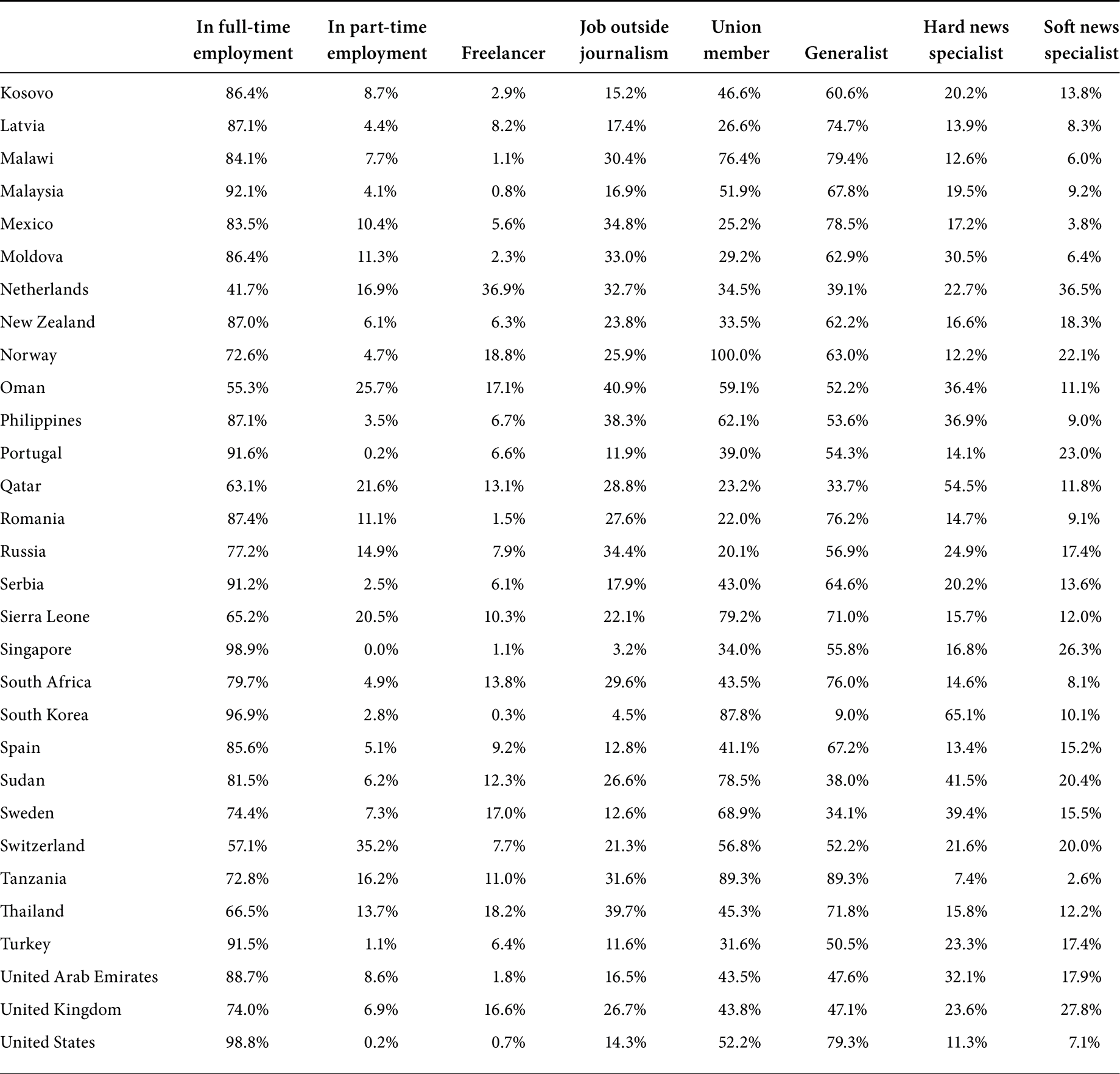

Employment Conditions and Working Patterns

While globally nearly four in five journalists were in full-time employment, journalists in some countries also faced precarious situations. An extreme example is the Netherlands, where only four out of ten journalists had full-time employment; one-third of the journalists here worked as freelancers, which likely has consequences for salaries (Vinken and IJdens 2013). High percentages of freelancers were found predominantly in Western countries; Italy stands out with around one-third of its journalists working as freelancers (table 4.3). In Denmark, Norway, Germany, Belgium, Finland, Canada, the UK, and Sweden, the figures ranged between 20 percent and 17 percent. In some countries, however, freelancing may not be as precarious an employment condition as it seems. In Germany, for example, a sizable minority of journalists, particularly in broadcasting, work as so-called feste freie Journalisten, a description that denotes freelancers who work regularly for the same organization and often receive a regular monthly income (Meyen and Springer 2009). Nevertheless, it would appear that the economic crisis of journalism across these highly developed media markets is indeed related to a higher percentage of the journalistic workforce working as freelancers. These developments do not appear to be as strong for journalists in Japan, Singapore, China, South Korea, and Ethiopia, to name a few countries, where the vast majority were employed full-time. We also found low percentages of full-time employed journalists in Oman, Switzerland, Argentina, and Brazil, where the figures range between 55 and 59 percent. In these countries, however, the larger percentage of journalists were part-time workers rather than freelancers. Still, these figures on part-time and freelance employment in a range of countries are evidence of a relatively insecure work environment.

As discussed earlier, in many countries journalists combine journalistic work with other jobs, even when they work full-time as journalists. While globally just under one-quarter of journalists had a job outside journalism, the proportion was considerably higher in developing economies (table 4.3). In Kenya, for example, at least four out of ten journalists had a second job outside journalism. In the economically more advanced regions of South and East Asia, however, journalists were much less likely to have a second job—for example, fewer than 10 percent of journalists had a second job outside journalism in China, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. Overall, these figures point to a link between national economic indicators and the likelihood of journalists having a second job that is outside journalism. Our understanding of the situation is confirmed by statistical analysis: we found a negative correlation between countries’ gross national income and the percentage of full-time journalists who also have jobs outside journalism (r = −.415, p < .001, N = 66; fig. 4.4).

We found the largest percentages of journalists who worked full-time but supplemented their income with another paid job in Kenya, Oman, Argentina, Thailand, and Indonesia. The opposite was the case for Spain, Sweden, India, China, Finland, South Korea, and Japan, where less than 10 percent of full-timers had a paid job outside journalism. At the same time, it is important to point out that income may not be the sole reason for holding a second job outside journalism. In some cases, journalists take another job for journalistic prestige rather than economic need. In Ecuador, for example, some senior managers of national media organizations hold other positions owing to their social reputation. These positions include appointments at universities, as well as political or business positions, and are thus more a case of wielding influence in society than of precariousness (Oller Alonso and Chavero 2016).

Figure 4.4 Full-time journalists with additional paid job and economic development

Source: World Bank, WJS; N = 67.

Analysis of journalists’ employment conditions also reveals that journalists in Europe were more likely than those elsewhere to occupy permanent positions. Of the seventeen countries with at least 90 percent of employed journalists with permanent contracts, ten are in Europe. However, Oman, Australia, the Philippines, Israel, Bhutan, Botswana, and South Africa also score high on this front. Only in Colombia (47 percent) and Kosovo (30 percent) did less than half the employed journalists have permanent contracts. Kosovo’s media market experienced a full restart after the end of the NATO intervention in 1999. Since then, most journalists and editors have had temporary contracts of either a few months or a year, which are typically renewed rather than turned into permanent contracts (Andresen, Hoxha, and Godole 2017).

Unionization is an important aspect of labor conditions in journalism. We found that in several countries, especially in the Nordic countries of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland, almost all the surveyed journalists were union members. This was also the case in Italy. In most other countries, journalists’ unions or associations have only a moderate foothold. In Japan and the Czech Republic, membership was less than 10 percent. Filip Láb and Alice Němcová Tejkalová (2016) consider the longstanding distrust in professional organizations responsible for the disinterest in joining a journalistic association in the Czech Republic. Few other countries displayed such low membership.

Among postcommunist societies, too, few had membership numbers as low as those in the Czech Republic; however, in countries in this group where a high percentage of women journalists was present (these include Russia, Romania, Estonia, Latvia, and Moldova), union membership ranged between 20 and 30 percent. The countries that resulted from the breakup of the former Yugoslavia, by comparison, had somewhat higher union membership, around 45 percent.

Canada and the United States both had just over 50 percent of their journalists in unions. Latin America emerges as a relatively coherent cluster, where membership ranged from 24 percent in Chile to 41 percent in Brazil. African countries such as Tanzania, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Malawi reported high percentages of union membership. In Malawi, membership was above 75 percent, but this was offset by low membership in Botswana and, especially, in Ethiopia. Neither Asia nor Europe presents a unified picture of union membership.

In Europe and North America, the drop in union membership is seen as a direct result of the transformation in the media sector, where the digital impact on news production and distribution has significantly altered the work of journalists. In an increasingly deregulated industry, which has also experienced fragmentation of the occupation, it is becoming more and more difficult for unions to represent journalists. The unions themselves are acutely aware of the changing “status of the journalist, the perception of the journalist occupation, permanent employees, and freelancers” (Bittner 2011, 10). The unions recognize that their organizational structures have not kept up with changes in the industry, notably in those countries that have been strongly affected by developments in their media industries. Still, in some countries, unlike the situation in earlier years, self-employed and freelance journalists and even unemployed journalists can be union members, a concession in the face of the decline in the number of the “journalistic core clientele” (Bittner 2011, 11).

Even if figures show that, for example, in the United States, those “covered by collective agreements earn up to 27 percent more than their non-unionized counterparts” (IFJ 2016), unions find it hard to attract freelance and young journalists. From among journalists in our study who were younger than 36 years, 40 percent belonged to an association, whereas among their older colleagues, 55 percent were union members. Marginally fewer female journalists (45 percent) than male journalists (49 percent) held membership in unions. While unions warn that nonmembership in their associations negatively influences wage negotiations, the gender gap in salaries, legal protection, and other conditions, such as pension payments, diversification in journalistic work, and fragmentation of the editorial workforce, may make it less likely that younger journalists become part of a distinct professional body.

Conclusion

The picture of an “average” journalist that emerges from our data is this: male, in his late thirties, holding a university degree most likely in journalism or communication studies, employed full-time, and with work experience of about twelve years. This snapshot, however, hides a vast array of variations. After all, 43 percent of journalists were women, an increase of about 10 percent compared to Weaver’s first global report on journalists (Weaver 1998b), and the participation of women in the journalistic workforce keeps rising. When we look at the distribution of countries where women journalists were in a majority or at least were equal in number to male journalists, distinct regional clusters become visible. States that have emerged from the former Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies as well as from the collapse of Yugoslavia are characterized by high percentages of women journalists, pointing to a more significant inclusion of women in the workforce that has continued beyond the communist era. While this has also translated into a higher percentage of women in top management and governance jobs in journalism than anywhere else in the world, remuneration has remained considerably below that of other countries. Cultural and societal traditions emerge as the most likely factors affecting female representation in the journalistic workforce. Importantly, when one looks at the global map, no distinct pattern emerges with regard to the influence of dominant religions.

A noticeable difference in the employment pattern of female and male journalists becomes apparent when we examine age ranges and seniority. More women than men enter the profession, but their participation drops sharply in the 35–45 and 45–55 age-groups. While the former can be attributed to women turning to family responsibilities, the latter attrition indicates that for women, journalism is far less of a lifelong attraction than it is for men. This attrition rate is also reflected in seniority within the newsroom, where men tend almost consistently to be in higher positions than women.

The average age of journalists around the globe was 38 years and the average median age 36 years, figures that have remained relatively stable over the past decade (Weaver and Willnat 2012) but mask a great diversity among countries. The age of journalists is an indication of employment patterns, and this is particularly evident in North America and Europe. Given the methodological decisions of the WJS—outlined in chapter 3—many young start-ups were not included in our sample, and our results are thus somewhat newsroom-centered. However, the age structure reveals a more profound underlying factor influencing the nature of newsroom cohorts. There is a strong correlation between the maturity of a country’s media sector and the age of journalists. Societies with a well-established press and wide readership in the second half of the twentieth century tend to have older journalists.

Professional experience, more than age and education, emerges as the most robust indicator of the stability and standing of the journalistic profession. On the one hand, there is a clear correlation between age and years of professional experience, with older journalists having many years of professional experience, helped by good employment conditions and salaries. Still, countries with low median years of professional experience are present on all continents. In some cases, a young cohort is the result of only recent media development in the country, but in most instances, low pay and poor working conditions create a situation whereby journalists do not remain in the job long. In many countries where journalists have low median years in the job, they have to resort to a second job to make ends meet. In other cases, young age and short professional experience can signal a somewhat contested position of journalism in that country and point to a structure of journalistic work where a young and fluid workforce is led by a small group of older and experienced journalists. Countries that have such a workforce configuration tend to concentrate on hard news, whereas in wealthier countries with an early and well-established mass media, more journalists work in soft news.

The world over, there is a definite move toward a fully tertiary-educated journalistic workforce, and young journalists mainly enter the profession with a degree in hand. On average, 85 percent of journalists had a university degree, an increase of more than 20 percent compared to the first global report on journalists (Weaver 1998b). Overall, two-thirds of working journalists had studied journalism and/or other communication subjects, with this being true especially for younger journalists. Women were generally more likely to have attended university and also more likely to have specialized in journalism or communication in their university education. University-based journalism education, which grew exponentially from the late 1980s onward before leveling out two decades later (Berger and Foote 2017), and which schools women predominantly, has had a noticeable influence on employment patterns. The effect of tertiary journalism education on the journalistic workforce needs further research.

The decline in union membership seems to be the most precise indicator of the changes occurring in journalism. It points not only to the fragmentation of the journalistic profession but also to the declining centrality of the newsroom (see chapter 10). In Europe and North America, the drop in union membership is seen as a direct result of the transformations in the media sector, where the digital impact on news production and distribution has had a significant impact on the work of journalists. In an increasingly deregulated industry, it is becoming ever more difficult for unions to represent journalists. With the changes in the status of journalists and the shifts in the perception and nature of the profession, it is harder for journalists to see themselves as part of a coherent professional body.