Journalists’ Awareness of Pressures on Their Work

Thomas Hanitzsch, Jyotika Ramaprasad, Jesus Arroyave, Rosa Berganza, Liesbeth Hermans, Jan Fredrik Hovden, Filip Láb, Corinna Lauerer, Alice Tejkalová, and Tim P. Vos

Journalists, news organizations, and journalism as an institution do not operate in a vacuum. A fundamental premise of the Worlds of Journalism Study is that the discourse of journalism cannot be understood in isolation from its various contexts. In other words, journalism is, to a considerable extent, an outcome of a multitude of restraining and enabling forces. Following some early work in the 1960s (Dexter and White 1964), journalism researchers have in recent years begun to pay increasing attention to this nexus of influences, most notably to factors stemming from political, economic, and organizational contexts (e.g., Hughes and Márquez-Ramírez 2017; Shoemaker and Vos 2009; Shoemaker and Reese 1996, 2013).

These influences materialize in different ways, sometimes in the form of draconian measures constraining press freedom, and at other times in a subtle fashion, as economic considerations in the newsroom. The story of Can Dündar, a prominent journalist and the former editor-in-chief of the Turkish opposition daily Cumhuriyet, is an example of direct restrictions on press freedom. In October 2016 Dündar was shot on his way to the courthouse, where he was to face a charge of “revealing state secrets.” Shouting “traitor,” the gunman fired two bullets at him. Dündar survived the assassination attempt and received a five-year sentence the same day. The verdict was the court’s decision on a criminal complaint filed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who was dissatisfied with Cumhuriyet exposing Turkish military support of Syrian rebels, a claim the government had denied. After the assassination attempt, Dündar said: “I don’t know who the attacker is, but I know who encouraged him and made me a target.”1

Turkey is listed as number 157 among 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index of 2018. However, political pressures also exist in Finland, a country with what is considered a free press and that has topped the index since 2010. In November 2016 Finnish public broadcaster YLE ran several stories about Terrafame, a taxpayer-funded mining company that had awarded a business contract to Katera Steel, owned by Prime Minister Juha Sipila’s uncles and cousins. Sipila, a former businessman, sent a series of emails to YLE complaining about its coverage of the issue. Shortly afterward, YLE appeared to have stopped its critical reporting about Katera Steel.2

Economic imperatives, too, are gaining ground in many media outlets, particularly in lifestyle and consumer media, and are thus creating their own set of pressures. An unnamed beauty editor of an Australian fashion magazine spoke of instances where key advertisers asked for editorial favors: “They will ask how much—we call it love—‘how much love are you going to give this brand in a year?’ It’s up to us to decide what we think is fair” (Hanusch, Hanitzsch, and Lauerer 2017).

As the examples above demonstrate, the daily work of journalists takes place in a complex nexus of occasionally conflicting contextual forces. Journalistic culture is the space where the relative impact and relevance of these influences are discursively articulated. This chapter presents an analysis of how journalists reflect on the various sources of influences on the news, how these perceptions differ across societies, and which factors drive cross-national differences. As we demonstrate in this chapter, the influences journalists perceive on their work can be meaningfully classified into five larger domains: political, economic, organizational, procedural, and personal networks. From among these five domains, political, economic, and organizational influences emerged as the strongest indicators of differences among national journalistic cultures. Journalists in non-Western, less democratic, and socioeconomically less developed countries perceived these influences on the news to be stronger than did journalists from countries characterized by greater freedoms and socioeconomic development.

Conceptualizing Perceived Influences on News Work

Researchers have conceptualized the contextual forces that limit and enable news production in terms of a hierarchy of influences. Early models commonly distinguished between individual, organizational, and institutional levels (e.g., Ettema, Whitney, and Wackman 1987), while recent work tends to envisage a slightly more complex array of forces. Perhaps most widely known is Pamela Shoemaker and Stephen Reese’s (1996, 2013) hierarchy-of-influences approach that organizes sources of influence on journalism into five hierarchically nested layers: the levels of the individual, routine practices, media organization, social institutions, and social systems. Though of U.S. origin, this classification of the driving forces of news production into a hierarchy of influences has proved to be empirically productive in a variety of cultural contexts (e.g., Pintak 2010; Relly, Zanger, and Fahmy 2015; Zhong and Newhagen 2009) and in comparative work in particular (e.g., Hanitzsch and Mellado 2011; Reese 2001).

While a growing scholarly consensus toward a common classification of influences echoes the work of Shoemaker and her colleagues, there is still little agreement on the relative importance of these levels. Early gatekeeping research suggested that individual factors reign supreme in the process of news production (Flegel and Chaffee 1971; White 1950), but other evidence points to a rather modest influence of journalists’ individual predispositions (Kepplinger, Brosius, and Staab 1991; Patterson and Donsbach 1996). Instead, organizational factors have been found to have a greater influence in shaping news production mostly through ownership, editorial supervision, decision-making and management routines, as well as news routines, and the allocation of time and editorial resources (Altheide 1976; Breed 1955; Fishman 1980; Gans 1979; Schlesinger 1978; Tuchman 1978; Weaver et al. 2007).

Several studies indicate the newsroom environment is an important source of influence and a strong predictor of journalists’ professional views (Hanitzsch, Hanusch, and Lauerer 2016; Shoemaker et al. 2001; Weaver et al. 2007). At the same time, researchers and journalists have long recognized the power of political factors, economic imperatives, and media structures (Bagdikian 1983; Preston and Metykova 2009; Whitney, Sumpter, and McQuail 2004). Consistent with this view, the societal level has emerged from the literature as an exceptionally important source of influence in all multilevel analyses of the previous wave of the WJS (Hanitzsch and Berganza 2012; Hanitzsch, Hanusch, and Lauerer 2016; Plaisance, Skewes, and Hanitzsch 2012; Reich and Hanitzsch 2013).

Clearly, even though these views are based on research, conclusions about the relative strength of these influences represent the theory-building efforts of academics as “outsiders.” Journalists may not fully perceive and thus not completely articulate the real power (relative strength) of some of these sources of influence because these influences are part of a reality that they take for granted. In the realities of journalistic practice, the way these influences come to bear on the process of news production has a discursive element. Journalists and news organizations constantly negotiate the power of these influences in daily news work (Carlson and Lewis 2015). In the process of professional socialization, however, many of these influences tend to be normalized to the extent that journalists conceive of them as the evident and “natural” way of doing journalism (Shoemaker and Vos 2009). As a result, journalists’ subjective perceptions of news influences may not fully map onto the theoretical schematas mentioned above.

Here again, the results of the first wave of the WJS warrant consideration. Based on a Principal Component Analysis of survey data from eighteen countries, the study identified six distinct domains of perceived influence: political, economic, organizational, procedural, professional, and reference groups (Hanitzsch et al. 2010). Journalists perceived organizational, professional, and procedural factors as being far more influential than political and economic influences. In that study it was reasoned that editorial management absorbs and filters political and economic pressures and redistributes them as organizational influences to subordinate journalists.

Toward a Comparative Index of Influences on News Work

This chapter is based on survey measures of how journalists perceive influences from nineteen potential sources. Tables A.1 and A.2 in the appendix list these sources, along with the corresponding descriptive statistics. In the questionnaire, we introduced the list of influences using the following wording: “Here is a list of potential sources of influence. Please tell me how much influence each of the following has on your work.” Journalists were given five options to answer the question, ranging from “extremely influential” (5) to “not influential” (1). We further collapsed the nineteen sources of influence into a parsimonious set of meaningful indexes: political influences, economic influences, organizational influences, procedural influences, and personal networks influences.3 The composite measures are based on theoretical rather than technical or statistical considerations, resulting in formative rather than reflective indexes (see chapter 3 for a methodological discussion). For each of the five indexes, we calculated a mean score reflecting the average score across all indicators that belong to the same index. A value of 5 points indicates the maximum perceived influence, and a value of 1 indicates no influence at all.

The first index, political influences, comprises the sources that originate from the political context, including politicians, government officials, and pressure groups. While the connection between these three groups of actors seems sufficiently intuitive, the inclusion of business representatives requires further explanation. Here we reason that people acting within the world of business—such as entrepreneurs, industrialists, protagonists of trade associations, and industrial lobbyists—may primarily pursue economic interests, but in most interactions with journalists, these interests are voiced and asserted in the political arena (Winters 2011). Representing, advocating, and imposing the interests of business and trade are inherently political acts with political implications. These activities may have only indirect economic implications, if any, for the news organization for which a journalist works.

Furthermore, in many countries, political and business elites are strongly intertwined, making it hard for journalists to make clear distinctions between them every time. Results from our previous study did indeed point to a strong link between business representatives and the larger concept of political influence (Hanitzsch et al. 2010).

Economic influences, the second index, refer to pressures in the newsroom related to economic and commercial concerns. These influences originate from a variety of sources that we measured through “profit expectations” of media companies and “advertising considerations” within the newsroom, and through “audience research and data” (indicator wording in the questionnaire). These factors, as well as their immediate consequences in the newsroom, reflect the fact that most media companies are profit-oriented endeavors that compete in a market economy. Economic influences are thus often seen as the single largest influence on news production, especially where news organizations’ primary goal is making a profit (Bagdikian 1983; Ettema and Whitney 1994). Even when that is not the case (such as for noncommercial and public service media), the high costs of modern news production and distribution introduce economic criteria at every stage, from selection to distribution (Whitney, Sumpter, and McQuail 2004).

The third index, organizational influences, includes pressures stemming from the hierarchical structures that govern decision-making processes and management routines of newsrooms and media organizations. The organized nature of news production is an essential feature of modern journalism, which puts the individual journalist “within the constraining boundaries of a fairly elaborate set of organizational control structures and processes” (Sigelman 1973, 146). Influence in the organizational domain is exercised on two important levels: within the newsroom (supervisors and higher-level editors, as well as editorial policy) and within the media organization (managers and owners). Obviously, the dimension of organizational influence transcends the traditional division between the newsroom and the larger structure of the media organization.

The fourth index captures what we have labeled procedural influences in publications from the earlier wave of the study (Hanitzsch et al. 2010, 15). These sources of influence relate to the various operational constraints journalists face in their daily tasks. The constraints usually materialize in the form of limited resources in terms of time and space, represented in our study through “time limits” and “available news-gathering resources” (questionnaire wording). Procedural influences relate to something journalists have or do not have but certainly need in order to perform their job properly. Access to information is such a “must have,” too. Furthermore, journalism ethics and media laws and regulation—though they may not seem as tangible as lack of time, resources, and access—also have practical consequences for news production. Journalism ethics and professional codes of conduct dictate a journalistic practice that is normatively desirable; these norms, however, may vary in influence in reality. Media laws and regulation are, in contrast, much more consequential for journalists, depending on how strongly they are instituted in a society (Shoemaker and Vos 2009). Made and enforced by the political system, media laws and regulations provide a space within which journalists can operate without facing legal consequences. Journalists are not necessarily aware of the political component of all these legal imperatives; more important to them are the practical and legal consequences certain illegal or unethical practices may have for their work.

Personal network influences constitute the fifth and final dimension. This index combines several factors, internal and external, most strongly related to journalists’ interactions with other people. Among the significant reference groups in the journalists’ professional domain are their peers on the editorial staff and their colleagues in other media. These groups are relevant because, just as in many other occupational fields, reputation as a value for journalists largely depends on the recognition their work receives from peers rather than from their consumers (the audience). Journalists monitor their colleagues as they compete with them, or as a means of self-ascertainment. Hence peer recognition is the central currency of professional reputation, and it determines a journalist’s “value” in the job market. Apart from their professional bonds, journalists maintain close social relationships through which they often develop an approximate sense of the audience. This noninstitutional component of the personal networks index relates to the potential influence of “friends, acquaintances, and family” (questionnaire wording) on a journalist’s work.

In the following sections we use the five indexes developed here rather than the individual sources of influence as measured in the original questionnaire. This allows us to present complex data relationships in a parsimonious fashion. As outlined in chapter 3, the indexes were constructed based on theoretical rather than statistical considerations. The political influences index combined pressures from “politicians,” “government officials,” “pressure groups,” and “business representatives,” while economic influences included references to “profit expectations,” “advertising considerations,” and “audience research and data.” The index for organizational influences averaged journalists’ perceived pressures from the “managers of the news organization,” “supervisors and higher editors,” “owners of news organizations,” and “editorial policy.” Procedural influences combined five sources, namely, “information access,” “journalism ethics,” “media laws and regulation,” “available news-gathering resources,” and “time limits.” Finally, personal networks influences referred to “friends, acquaintances, family,” “colleagues in other media,” and “peers on the staff.”

Perceived Influences: The Big Picture

To assess the relative strength of the five domains of influence on a global level, we considered the mean scores and their distribution (reported in table 5.1 and illustrated in fig. 5.1). We found that the dimensions are arranged in a hierarchical structure in which journalists see procedural and organizational influences as much more powerful in their work than influences from personal networks or economic and political factors. This result reaffirms a pattern extracted from the first wave of the study (Hanitzsch et al. 2010; Hanitzsch, Hanusch, and Lauerer 2016) and replicates findings from other, similar studies (e.g., Shoemaker et al. 2001; Weaver et al. 2007). It is also a reminder that the hierarchy of influences model that places social systems atop the hierarchy is simply a catalog of influences arranged by relative abstraction rather than a statement about their relative influence (Shoemaker and Reese 1996).

Table 5.1 Perceived influences across countries

|

N |

Meana |

Fb |

Eta2 |

|||||

|

Procedural influences |

27,249 |

3.75 |

65.08 |

.136 |

||||

|

Organizational influences |

27,011 |

3.30 |

83.68 |

.170 |

||||

|

Economic influences |

26,646 |

2.74 |

83.37 |

.172 |

||||

|

Personal networks influences |

27,211 |

2.62 |

42.15 |

.093 |

||||

|

Political influences |

26,803 |

2.25 |

116.71 |

.224 |

||||

|

a Weighted. b df = 66; all p < .001. |

||||||||

More specifically, journalists around the world perceive procedural factors to be the strongest set of influences on news work. Arguably, the strength of this dimension resides in the fact that it is composed of influences closely related to key processes of journalistic work and is experienced unmediated by journalists. Particularly, limited access and time to do news work is a tangible influence affecting journalistic work fundamentally and immediately. Despite their high perceived strength overall, procedural influences vary substantially by country. The eta-squared measure indicates that differences in the national contexts account for almost 14 percent of the overall variance in procedural influences, a moderate effect. Figure 5.1 demonstrates that across the sixty-seven societies, the average scores are nearly normally distributed; there is no hint of any substantive country clusters.

Figure 5.1 Journalists’ perceived influences across countries (distribution of country means)

Source: WJS; N = 67.

Note: Scale: 5 = “extremely influential” … 1 = “not influential.”

Not surprisingly, organizational influences were perceived as the second-strongest influence on journalistic work in all sixty-seven countries. News organizations maintain a grip on their journalistic staff through a clear chain of command and supervision, through editorial policy, and through the cultivation of a distinct newsroom culture. While their struggle for autonomy keeps journalists alert about any encroachments and, to some extent, protects them from certain external influences, such as politics and business, it leaves them defenseless against organizational forces. Levels of organizational influence vary significantly across countries, with national differences accounting for 17 percent of the overall variance. The double-peaked (bimodal) distribution of country averages suggests some qualitative differences between groups of countries that deserve further inspection, and which will be discussed later in this chapter.

Economic influences scored the third highest on average, though journalists perceived these forces to have only some or little influence. The global analysis points to considerable differences among countries; the amount of variation accounted for by cross-national differences is slightly higher (17 percent) than for organizational influences. Again, a double-peaked distribution of average scores calls for examining cross-national patterns. Similar to economic influences, the influence of personal networks was, on a global scale, perceived to be only moderate by most respondents. The countries differ on this dimension, too, but to a smaller extent than for the other four domains. However, family members and friends, as well as colleagues and peers, are perceived to have a larger impact on news work than system-related country-level structures.

Political influences, lastly, make up the domain of influence that has, in the view of journalists, the least power to shape the daily work of newsmakers. The extent to which political factors matter, however, depends strongly on the national context. The political forces domain, from among the five influence domains, exhibits the greatest variation across nations, with country differences accounting for almost one-quarter of the overall variability in the data. Therefore perceived political influences are a key marker of differences in journalistic cultures around the globe. The bimodal distribution of average scores across the sixty-seven countries, as shown in figure 5.1, clearly points to substantive differences between at least two different groups of countries, which we will explore further in the following sections.

The relatively moderate perceived importance of political and economic factors may well be counterintuitive. Given the overwhelming evidence for the existence of political and economic influence reported in large parts of the academic literature, some of which we have cited above, the objective power of political and economic influences can hardly be denied. These influences have real and often critical consequences in everyday news work. Hence the low perceived importance of political and economic factors—compared to other sources of influence—does not mean that these forces have little relevance to the production of news. To the contrary, it is quite possible that these factors are actually more powerful in reality than journalists’ perceptions suggest.

We believe that the inconsistency between journalists’ perceptions of influences and their impact as discussed in much of the journalism literature is reflecting the epistemological schism between “objective” and “real-existing” influences, on the one hand, and perceived influence, on the other (Reich and Hanitzsch 2013). Objective influences do exist in the real world; they have real power, and they make a practical difference in the work of journalists. Perceived influences, in contrast, refer to journalists’ subjective perceptions of these forces, which may not necessarily correspond to the objective power of influences. Journalists’ perceptions may thus only partly represent the reality of news making. This is an important caveat to keep in mind in interpreting the findings of this study.

Some explanations for why the objective reality of these influences may not be clearly evident to journalists are proffered. As we pointed out in our analyses from the first wave of the study, these influences may not necessarily appear as evident to all journalists equally (Hanitzsch et al. 2010). Let us return to the examples mentioned in the introduction to this chapter: not all journalists in Turkey live as dangerously as Can Dündar, who survived an assassination attempt, but they may do so when they start reporting too critically on security-related issues. Similarly, not all Australian journalists may be asked for editorial favors by advertisers in the way a beauty editor from a fashion magazine (quoted earlier) said she was. Journalists might also tend to consciously negate, and thus not acknowledge as easily, political and, even more so, economic influences as part of a professional ideology according to which journalism is supposed to operate independently of political and economic interests.

Presumably political and economic pressures appear to be less important in journalists’ perceptions because these influences are further removed from their daily practice than, for example, the influence of norms and routines. Political and economic influences are likely less tangible and much more clandestine. Their significance is masked by organizational and procedural influences that have a much stronger grip on journalists’ everyday practice. Rank-and-file journalists, we believe, rarely experience political and economic influences in a direct and immediate fashion. We think that the power of political and economic influences is anticipated and absorbed by the organization’s news management, and these influences are subsequently filtered, negotiated, and redistributed to individual journalists, where they are finally internalized and thus appear as organizational and procedural influences (Hanitzsch et al. 2010). News organizations are therefore likely to function in many cases as a mediator of external interests and pressures rather than as a buffer protecting journalists from direct exposure to these influences. We will return to these issues in the concluding section of this chapter.

Strong ties between political and economic influences, on the one hand, and organizational imperatives, on the other, are particularly common in Latin America, where many major news organizations belong to longstanding dynasties well connected to the world of politics (Waisbord 2000). Whereas in other parts of the world this would constitute a serious conflict of interest, Latin American journalists accustomed to this situation have learned to accept this linkage as the norm (Arroyave and Barrios 2012; Waisbord 2009). Still, journalists who question this linkage will suffer reprisals, as in the case of Carmen Aristegui, Mexico’s most prominent radio personality. In 2011 she was dismissed after publicly commenting on then-president Felipe Calderón’s possible alcohol problems. While her employer reinstated her only a few days later following public protests,4 four years later she was again abruptly fired after she exposed a corruption scandal involving President Enrique Peña Nieto. Her dismissal eventually opened a national debate about corruption and helped anticorruption legislation that was working its way through Congress.5 In this and many other cases, political and economic pressures are intertwined with organizational influence.

Differences Across Countries

As noted above, cross-national differences in our study were especially large with regard to political, economic, and organizational influences. In the following section we explore these differences further to extract general patterns of global similarities and differences. Table 5.2 reports a country-wise breakdown of average scores and standard deviations for the five domains of influence. Readers specifically interested in national differences for the various individual sources of influence may want to consult tables A.1 and A.2.

The extent to which journalists perceive political influences on their work to be weak or strong generally reflects differences between political systems and tends to follow international geographical divides. European nations dominate the top twenty countries where journalists perceived the least political influence; Canada, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, and the United States also belong to this group. Typically, journalists report relatively little political influence in developed democracies, that is, political systems that grant journalists high levels of press freedom and political liberties. Among the Western countries in the study, Australia and Spain had the highest scores on political influence, setting them somewhat apart from the other Western nations and—somewhat surprisingly—in close proximity to Russia.

Table 5.2 Perceived influences—differences between countries

For Spain, this finding may be less surprising than it seems at first sight. The country’s media system is closely linked with political powers, historically and especially since the democratic transition. Broadcasting media, both public and private, are tightly regulated through a government licensing system, and regional and local media strongly depend on advertising revenues from public institutions (Berganza, Herrero-Jiménez, and Arcila-Calderón 2016). In Australia, there is a notoriously high concentration of media ownership, and, during the time of our survey, there was considerable debate in the country about the federal government’s inquiry into media regulation and media reform in 2011 and 2012. The inquiry, and subsequent government plans to establish a statutory body to police the media, was criticized by many media organizations as a politically motivated attempt to intervene in journalistic freedoms (Flew and Swift 2013). Except for these two countries, however, our results point to a robust association between democratic development and lower perceived power of political influences on news production.

Russia, too, deserves special mention here. As indicated, Russian journalists reported, on average, political influence levels equal to those reported by Australian and Spanish journalists. Counterintuitive as this result may be, because one may expect the score to be higher for Russia, it may be a good example of how news management absorbs and redistributes political pressures to working journalists in the form of organizational influence.

After Vladimir Putin rose to power, Russian TV networks became owned by the state or by companies that functioned as corporate arms of the government (Specter 2007). Two of the three main nationwide TV networks, Channel One and Russia TV, are controlled by the state. Energy giant Gazprom owns several television channels (notably, TNT and NTV), radio stations, and print outlets (including Izvestia, until 2008). Anna Kachkayeva, former dean of the Faculty of Media Communications at the Moscow-based Higher School of Economics, calls it a system of contacts and agreements between the Kremlin and the heads of television networks: “There is no need to start every day with instructions. It is all done with winks and nods. They meet at the end of the week, and the problem, for TV and even in the printed press, is that self-censorship is worse than any other kind. Journalists know—they can feel—what is allowed and what is not” (Specter 2007). The report by Freedom House in 2016 concludes that the nationalistic tone of the dominant Russian media continued to drown out independent and critical journalism.6

Journalists in African countries, in Turkey (where our study was conducted before the failed coup attempt of 2016), in the Gulf states, and in large parts of East, South, and Southeast Asia report relatively strong political influences. In these regions, more often than not journalists work under conditions of heavy political interference in freedom of the press and tight restrictions on freedom of speech. As we will see in the following chapters, these settings tend to produce a culture of journalism that copes with these pressures in its own way, a culture that helps journalists survive in an often hostile environment. Political influence is also seen as high to moderate in most parts of Latin America, with El Salvador emerging on top of the list in terms of influence strength. Among all Asian countries in this study, only Japan deviates from the overall pattern, as journalism there has broadly followed a Western paradigm since the end of World War II.

Geographical divides also matter with regard to economic influences on journalism. The perceived power of economic imperatives is smallest in the Scandinavian countries, in North America, and in Belgium, France, Switzerland, and Austria. Except for the United States, these countries maintain strong public service broadcasting institutions. Scandinavian societies are exemplary of this type of media system, where the state has a strong role in regulating and funding the media industry. Public service media are not limited to the broadcasting sector alone; the state also provides subsidies for print outlets in all countries but Iceland. Ahva et al. (2017) therefore see low levels of economic pressure as a distinctive feature of Nordic journalism. In these societies, the impact of commercialization and competition is mitigated through public regulation and funding. Furthermore, there are obvious similarities between Scandinavia, Estonia, and Latvia. The two Baltic countries have instituted a strong public service broadcasting media, and some of the significant commercial media organizations there are owned by Swedish and Finnish media houses.

The low levels of economic influence reported by U.S. journalists, at least in comparison to other countries in the sample, is notable because complaints about strong commercialization and the increasing power of economic imperatives are particularly rampant in the literature on American journalism (McChesney 1999). While their media outlets are overwhelmingly commercially supported, U.S. journalists experience this influence only indirectly and rarely acknowledge it (Beam, Weaver, and Brownlee 2009). Given the strong normative firewall between commercial considerations and news decisions, journalists find acknowledging a breach difficult (Artemas, Vos, and Duffy 2018; Coddington 2015). This, again, reminds us that perceptions about influences should be treated with a certain degree of caution. Journalists’ interview responses may not fully reflect the material conditions on the ground, but they make apparent the way in which the power of these influences is articulated in institutional discourse.

Our results also show a noteworthy split for Europe that largely follows the geographic divide between Western and Eastern Europe. Journalists reported stronger economic influences in Eastern Europe; these factors were perceived as being remarkably potent in Bulgaria and Hungary. After almost three decades of political-economic transition in Eastern Europe, tight control of the media by the state has been replaced by the now omnipresent power of market forces, but without a long tradition of a business-news firewall. At the same time, journalists in Western European countries feel their work is less influenced by economic pressures than do their colleagues in other parts of the world.

Economic influence is seen as particularly pronounced in Asia (most specifically in Thailand, India, Malaysia, and South Korea), in the Gulf region, and in most parts of Africa. Pressures stemming from corporate profit expectations, advertising considerations, and market research are particularly strong in El Salvador and Mexico, as well as in Colombia and Ecuador. As Silvio Waisbord (2009, 393) argues, political and economic influences often appear heavily intertwined in Latin American journalism. Presidents and governors have the habit of manipulating the allocation of lucrative advertising contracts and a wide array of business opportunities “in order to court support from private media, feed the ambitions of sycophantic moguls, and prop up their own media empires.”

A clear regional pattern also emerges from a cross-national analysis of perceived organizational influences on the news. Again, most pronounced is a division along the lines of Western and non-Western countries. Influences stemming from within the newsroom (editorial policy, supervisors, and higher editors) and from within the media organization (managers and owners) are seen as particularly powerful in Africa, Latin America, Russia, and most parts of Asia, including the Gulf region. Arguably, this pattern can be placed in the context of cross-cultural research on how workplace-related inequalities are generally perceived in a given society. Geert Hofstede (2001), for instance, noted that individuals from non-Western regions are more likely to accept power inequalities in organizations. Thus it seems reasonable to assume that in these societies, one may find a stronger and more pronounced hierarchy within the newsroom and the media organization, in which senior journalists and those in managerial positions have much more authority in shaping operational decisions and long-term editorial policy. We think that such a hierarchical structure and greater acquiescence to this structure are likely explanations for the stronger perceived organizational influence in non-Western countries.

Organizational cultures in other societies, by way of contrast, seem to institute a much flatter editorial hierarchy and a more egalitarian organization of journalistic labor. This is particularly true of the Nordic countries as well as of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and most parts of Western Europe. In these countries, organizational influence was seen as exceptionally weak. This finding again resonates with Hofstede’s (2001) comparative work, which generally points to lower acceptance of power inequalities in Western countries, most notably in Scandinavia. The contextual analysis presented in the following section supports this conclusion.

Among the Western societies included in the study, Spanish journalists reported the strongest levels of organizational influence. This finding puts Spain in close proximity to Latin America, where interactions between journalists tend to be less egalitarian and editorial hierarchies much stricter. Overall, it is worth noting that similarities between Spanish and Latin American journalists seem to be a general finding of this study, as the subsequent chapters will demonstrate (e.g., chapters 7 and 11).

Qatar does not follow the overall trend; here journalists reported relatively little organizational influence on their day-to-day work. We believe that a reasonable explanation for this finding is the relatively large proportion of journalists interviewed in Qatar who worked for Al Jazeera. These journalists reported significantly less organizational influence than did their counterparts in other newsrooms in the country. Although the government of Qatar owns the television network, journalists working for the network enjoy considerable editorial freedom. The fact that Al Jazeera journalists perceive organizational influence as relatively weak—as compared with journalists from other countries in this part of the world—is thus likely the result of an organizational culture that, according to Mohamed Zayani and Sofiane Sahraoui (2007), emphasizes independent thinking and individual initiative more than do other news media in the region.

The cross-national pattern for procedural and personal network influences is less clear-cut and does not seem to entirely follow the more common geographical, political, or cultural groupings. Generally, journalists perceived procedural influences to be stronger in the Anglo-Saxon world (notably, Australia and the United States), in Africa and India, in Southeast Asia, and in several Eastern European countries. Procedural influences appeared less powerful in large parts of continental Western Europe, in Latin America, and in a few other countries, such as Japan, Turkey, and China.

For personal networks, journalists from most parts of Asia, Eastern Europe, and Russia reported high levels of influence. The perceived influence of peers and colleagues as well as friends, acquaintances, and family turned out to be much less pronounced throughout continental Western Europe, Canada, and Australia. The pattern was mixed for Africa and Latin America. Interesting as these differences are, a detailed discussion of them requires a focused, fine-grained analysis that is beyond the scope of this book.

To gain a better idea of potential cross-national configurations, we mapped the cross-national similarities and differences onto a two-dimensional plot. We limited this analysis to political, economic, and organizational influences, as these emerged as the most meaningful signifiers of cross-national difference. Figure 5.2 shows a country map based on an application of Multidimensional Scaling.7 The interpretation of the plot is rather straightforward; spatial proximities on the map represent similarities between countries across political, economic, and organizational influences.8

Overall, figure 5.2 exhibits a pattern that points not only to differences between Western and non-Western countries, as well as between developed and developing nations, but also to some more fine-grained disparities within these larger groups. To the right side of the figure are the continental Western European nations that cluster together owing to relatively weak influences from the political, economic, and organizational domains. These countries maintain strong public service media institutions; journalists and large parts of the population consider the media as a public good. In many regions, such as Scandinavia and France, public funding is not limited to public service broadcasting channels alone; it is also provided to print media outlets. Australia, Britain, and the United States are located at the left fringe of this particular cluster of countries on the map, underscoring their unique status in the Western world.

Figure 5.2 Journalists’ perceived influences—differences between countries

Source: WJS; N = 67.

Note: Multidimensional Scaling plot based on Euclidean distances using Alscal.

The two Baltic nations of Estonia and Latvia are close to the cluster of Western European countries (Estonia, in particular, mimicking the Scandinavian example), as are many societies in Eastern Europe, most notably the Czech Republic, Croatia, Romania, Moldova, Albania, and Kosovo. Broadly speaking, the transformation of media systems in Central and Eastern European countries has resulted in the Westernization of journalism but not necessarily in the homogenization of journalistic cultures in the region. Journalism in this region is traversing different paths, as our results clearly show. Bulgaria, Serbia, and Hungary exhibit a pattern distinctly different from that in the other countries, especially in terms of stronger perceived economic and organizational influences. These three countries are in close proximity to Russia in terms of the strength of these influences.

The left side of figure 5.2 is occupied solely by countries from the non-Western world. This includes all African and most Asian countries, as well as the three Gulf countries. Here journalists perceive all domains of influence on the news as being generally strong. Heavy perceived political influence seems to be a distinctive feature in these journalistic cultures. The similarities among African countries—with the exception of Tanzania, which is a clear outlier—are particularly striking. Most journalists across the continent said they operated under heavy organizational and political constraints. Differences among East, Southeast, and South Asian countries are slightly larger by comparison, with journalists in Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Philippines most similar to their colleagues in the Western world. Thailand, a country oscillating between parliamentary democracy and military rule for decades, occupies a unique space to the far left of figure 5.2, with journalists consistently reporting enormous pressures from nearly all domains of influence.

Notably, figure 5.2 provides evidence that Japan and Hong Kong represent regionally distinct journalistic cultures, which underlines their rather exclusive position in the larger Asian context. Although mainland China is gradually gaining control over Hong Kong’s uniquely cosmopolitan press environment, the British cultural legacy is still visible in the local journalism culture. Japan, in contrast, adopted a Western approach to journalism when media outlets across the country fell under the control of U.S. Headquarters after the Second World War. Since then, Japan has instituted an exceptionally strong public broadcasting organization in the form of Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai (NHK), which has a potent grip on public discourse. Further, political changes in the 1990s increased the power of journalists to report even more independently (Sugiyama 2000).

Japan and Hong Kong are not the only examples of hybrid journalistic cultures. Turkey, Qatar, and Singapore occupy unique positions at the top of figure 5.2, relatively far removed from all other countries included in the study. In terms of perceived influences on the news, journalism in these three countries seems to combine characteristics from journalistic cultures in both Western and non-Western societies in ways that create a work environment characterized by weak organizational and stronger political influence.

Another interesting observation from figure 5.2 is that despite their obvious similarities, journalistic environments in Latin America broadly split into two subgroups. One cluster of countries consists of Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Mexico, where perceived political, economic, and organizational pressures combined tend to be considerably higher than in the second group. Journalistic cultures in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, by contrast, appear to be much more Westernized, with relatively lower levels of such influence. Still, the Latin American countries are proximate to one another and with Spain, indicating similarities between the region and Spain. The cultural bonds between Spain and its former colonies seem to pull these journalistic cultures in similar directions; much more than we found to be the case for Britain and its fallen colonial empire. Journalism in Brazil, a Portuguese colony for more than three centuries, seems to follow this path, too.

Contextualizing Perceived Influence on News Work

As noted above, the examination of differences and similarities among countries points to a number of factors underpinning journalists’ perceptions of news influences. These factors broadly fall into the three societal contexts of journalistic culture outlined in chapter 2: politics and governance, socioeconomic development, and cultural value systems. In this section we examine these factors more closely, using contextual measures provided by international institutions, such as Freedom House, the World Bank, and the World Values Survey. These measures are strongly interrelated, often with correlations greater than r = .80. Societies scoring high in terms of quality of democracy, for instance, tend to grant greater freedom to the media, give more authority to the law to constrain individual and institutional behavior, exercise more transparency, fight corruption more, and have higher levels of human and economic development (see table A.8 in the appendix).

Table 5.3 reports correlations between journalists’ perceived influences and relevant contextual factors. With the exception of procedural constraints, all domains of influence are related to press freedom as measured by both Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders. Associations are particularly strong for political and economic pressures, suggesting that, across countries, journalists’ perceptions of the strength of these influences correspond well with external measures of media freedom. Press freedom, however, may well work as an intermediary in the journalists’ perceptual structure of influences on the news. As the correlations reported in table 5.3 indicate, journalists’ perceptions of influence—particularly those stemming from the political, economic, and organizational domains—are mainly driven by democratic performance.

Table 5.3 Correlates of perceived influences on news work (correlation coefficients)

|

Political influence |

Economic influence |

Organizational influence |

Procedural influence |

Personal networks influence |

||||||

|

Press freedom (FH)a |

−.782*** |

−.691*** |

−.593*** |

−.082 |

−.408*** |

|||||

|

Press freedom (RSF)b |

−.651*** |

−.644*** |

−.505*** |

−.066 |

−.279* |

|||||

|

Democracyc |

−.691*** |

−.649*** |

−.546*** |

−.046 |

−.401*** |

|||||

|

Rule of lawd |

−.481*** |

−.584*** |

−.633*** |

−.320** |

−.154 |

|||||

|

GNI per capitae |

−.412*** |

−.608*** |

−.701*** |

−.484*** |

−.216 |

|||||

|

Transparencyf |

−.439*** |

−.621*** |

−.630*** |

−.378** |

−.161 |

|||||

|

Human developmentg |

−.576*** |

−.630*** |

−.718*** |

−.479*** |

−.261* |

|||||

|

Emancipative valuesh |

−.543*** |

−.619*** |

−.502*** |

−.146 |

−.207 |

|||||

|

Acceptance of power inequalityi |

.511*** |

.606*** |

.571*** |

.144 |

.307* |

Notes: Pearson’s correlation coefficient. ***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05; N = 67 unless otherwise indicated.

a Freedom House; Freedom of the Press Index; scale reversed.

b Reporters Without Borders; World Press Freedom Index; scale reversed.

c Economist Intelligence Unit; EIU Democracy Index; N = 66.

d World Bank; percentile rank.

e World Bank; Atlas method, current US$; N = 66.

f Transparency International; Corruption Perceptions Index.

g UNDP; Human Development Index; N = 66.

h Scores calculated based on WVS/EVS data; N = 58.

i Geert Hofstede, https://

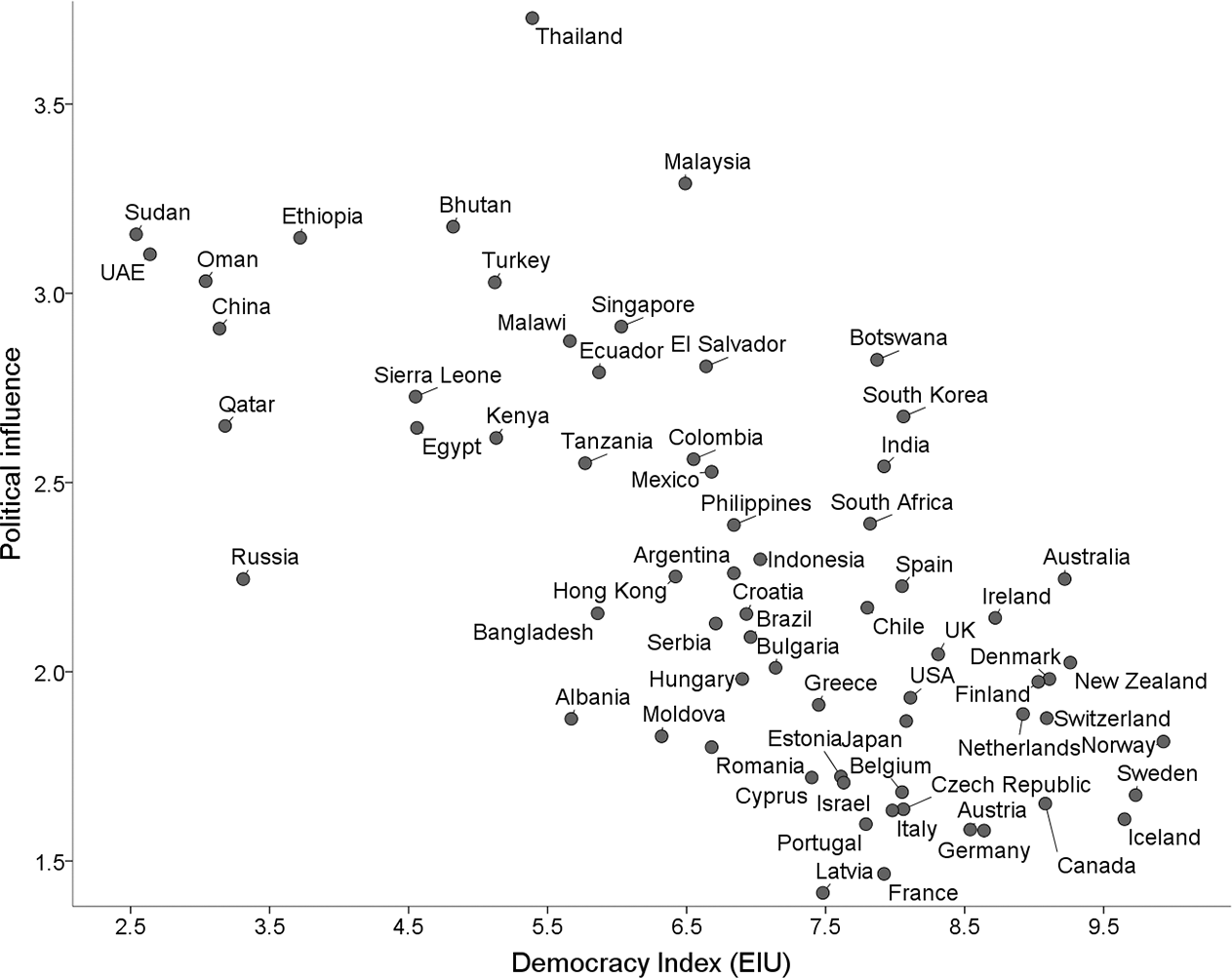

Figure 5.3 provides a good illustration of the relationship between perceived political influence and quality of democracy as measured annually by the Economist Intelligence Unit. Journalists in democratic societies clearly perceive less political influence on their work, which is consistent with other studies that point to the importance of the political context for journalistic freedoms (Hallin and Mancini 2004; Hanitzsch and Mellado 2011; Soloski 1989). The location of countries in figure 5.3 does not follow a straight line, however, indicating that similar political conditions do not necessarily coincide with similar levels of perceived influence. The comparison between Botswana and France, both scoring high on the Economic Intelligence Unit democracy index but different in perceived influence, is a case in point.

Figure 5.3 Journalists’ perceived political influences and quality of democracy

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit, WJS; N = 66.

From table 5.3 we can see that perceived political influences are less pronounced in societies that are socioeconomically well developed, where populations have greater appreciation for emancipative values, and where power inequalities are less tolerated, though correlations tend to be slightly weaker. These findings need to be put in the context of a long-term cultural drift, or “emancipative value change,” which emphasizes the importance of individual autonomy, self-expression, and free choice (Inglehart and Welzel 2005). In societies where people have a strong preference for emancipative values, journalists tend to have emancipated themselves from all kinds of authority, including political actors and government institutions. Thus journalists would consider overt and strong political influence to be a transgression of institutional boundaries. At the same time, journalists face stronger political influences in societies that have more tolerance for inequalities in terms of how power is distributed (Hofstede 1998). Hence our analysis suggests that, as was argued in chapter 2, cultural and social value structures do indeed shape journalistic cultures considerably; overall, however, political factors seem to have greater weight in the equation.

Correlations for economic and organizational influences broadly show a similar pattern, perhaps with the difference that economic influences are more strongly related to human and economic development, transparency (or the absence of corruption), and the extent to which people embrace emancipative values. Organizational influences on the news are most strongly associated with human and economic development, the rule of law, and transparency. The overall pattern shows that journalists perceive pressures in all three domains of influence as stronger in less democratic and socioeconomically less developed countries as well as in societies with less appreciation for emancipative values and a greater tolerance for power inequality. Procedural influences are mainly related to social and economic development; journalists feel less constrained by operational pressures such as limited resources, information access, and media laws in countries that score higher on economic well-being and human development.

Human development, finally, is the only contextual factor that is significantly related to journalists’ perceived influence on all five levels. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) measures human development from various indicators of life expectancy, education, and per capita income.9 Our results reinforce the conclusion that as far as perceived influences on the news are concerned, differences between journalistic cultures significantly track along established classifications of developed and less developed countries, broadly mapping onto a divide between Western and non-Western societies.

Conclusions

In this chapter we have examined perceived influences on the news—the first extrinsic dimension of journalistic culture—based on journalists’ responses to a set of standardized questions. The purpose was not to gather data on such influences as they objectively exist, which would have required a different research strategy, but to get a sense of how journalists perceive these pressures in everyday news work and how influences are discursively articulated. Relying on journalists’ perceptions and recollections of influences on their work has obvious disadvantages. Their answers to the survey may be tailored to what respondents believe researchers want to hear from them, or to what journalists consider normatively desirable. Furthermore, because survey questionnaires typically elicit interview responses to a fixed set of questions using predefined answer options, responses may be an effect of the research protocol and not fully represent objective realities on the ground. At the same time, however, as researchers we also take journalists’ interview responses for what they are: reasonable perceptions of a social and professional reality.

Keeping these caveats in mind, we identified five major domains of influence: political, economic, organizational, procedural, and personal networks. In the following chapters we consider these measures as contextual configurations, among others, that produce a diversity of journalistic cultures. The analysis for this chapter revealed that across the five domains, procedural and organizational influences mattered more in the view of journalists than influences from the political, economic, and personal networks domains. We do not believe, however, that the weak political and economic pressures reported by journalists necessarily reflect a hierarchy of influences as it exists on the ground. Journalists may not want to acknowledge the influence of these domains. They may not be equally or directly exposed to these influences. They may not be fully aware of them, or they may even systematically underestimate the power of these forces. Analyzing the global pattern of influences on the news, we argue that political and economic influences may be internalized by editorial management and transformed into organizational and procedural influences. However, it is impossible to test this hypothesis with the data set at hand. Hence the possible transformation of external influence into internal constraints through editorial routines is an issue that merits further attention from researchers.

As indicated above, the celebrated ideal of editorial independence may well encourage many journalists to deny or dismiss the unpleasant reality of economic imperatives in the newsroom. This, of course, has interesting implications in its own right. It is difficult to solve the problem of economic influence (or find an appropriate response to it) when journalists deny or dismiss the problem’s very existence. Hence the low levels of political and economic pressures that journalists reported may be seen as a defensive discursive strategy to maintain the institutional boundaries of journalism in a time when they have become alarmingly porous.

The extent to which journalists perceive political, economic, and organizational influences on the news as weak or strong emerged as the strongest indicator of cross-national differences. This is particularly true for political influences—a finding that resonates with the literature on the relationship between media systems and the political environment (Hallin and Mancini 2004). Overall, we found a pattern that reflects the differences between political systems and tracks along familiar geographical divides. Disparities between countries map neatly onto common classifications of Western and non-Western countries, as well as developed and developing nations. While there were notable variations within these groups, perceived influences on the news tend to be stronger in non-Western, less democratic, and socioeconomically less developed countries.

From a classic modernization approach, the finding mentioned above may invite some readers to think that parts of the “less developed” world still need to “catch up” with journalistic standards established in the West as it pertains to issues discussed in this chapter. However, we suggest an alternative reading. The idea of journalism as an institutional endeavor that is independent of external forces may be a noble, viable, and proper ambition in most Western countries—albeit an ambition that likely outpaces reality—but cultural norms and professional realities are clearly different in other parts of the world. Ultimately, journalistic cultures need to strike their own balance between editorial independence, on the one hand, and cultural norms and social realities, on the other.

Notes

1. Samuel Osborne, “Turkish Journalist Survives Assassination Attempt Before Receiving 5 Year Sentence for ‘Revealing State Secrets,’ ” Independent, May 6, 2016, http://

2. Richard Milne, “Finnish PM’s Emails Land Him in Press Freedom Row,” Financial Times, November 30, 2016, https://

3. It is worth noting, however, that two of the five indexes—procedural influences and personal networks influences—slightly deviate from the way we conceptualized them in our previous study, mostly because of some modifications of the indicators (Hanitzsch et al. 2010).

4. Edgar Sigler, “Los 17 días que ‘condenaron’ a MVS,” Expansión, August 22, 2012, http://

5. Elisabeth Malkin, “In Mexico, Firing of Carmen Aristegui Highlights Rising Pressures on News Media,” New York Times, March 27, 2015, https://

6. Freedom House, Freedom of the Press Report, Russia, 2016, https://

7. Multidimensional Scaling is a statistical technique that represents multivariate similarities (or differences) between empirical observations as spatial proximities in a space of low dimensionality. In figure 5.2 locations of countries on the map represent relative similarities among them with respect to journalists’ perceptions of political, economic, and organizational influences.

8. Goodness of fit: Stress1 = .07; R2 = .98. The statistical properties point to a solution that represents multidimensional similarities reasonably well, according to Borg and Groenen (1997).

9. United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Reports, 2015, Technical Notes, http://