CHAPTER FIVE

The Pursuit of National Airlines

Seizing Opportunities

1978–1979

AS WE were about to enter the post-deregulation period, our most immediate need was for the strengthening of our balance sheet, and in April 1978, we raised more than $27 million through the sale of units of subordinated debt and common stock in what was then a very large public financing for a regional airline. This gave TIA substantially greater liquidity and flexibility to pursue various strategies for dealing with deregulation. It certainly gave us more downside protection.

We also raised our visibility in the capital markets by listing our stock on the American Stock Exchange. At the ceremony for our formal induction into AMEX, a limousine was sent to our New York offices to take a group of us downtown. On the way, it occurred to me that my father, my very first financial adviser, would get a big kick out of this moment, so I had the driver stop by the beauty shop to see if my dad was free to join us. It didn’t take much persuasion. Dad was beaming all through the ceremony. All my life, he had drummed into me the message that anything was possible in his adopted homeland, and there I was, running a company listed on the American Stock Exchange. It was truly a proud day for both of us.

With this new infusion of capital, it didn’t take us long to come up with a rather unplanned use for it. On Memorial Day weekend, both Bob Carney and I took home some other airlines’ annual and quarterly reports, and both of us noticed that National Airlines presented an opportunity: its shares seemed unusually depressed. While we had looked at some potential merger targets among the ranks of undervalued and underperforming airlines, Florida-based National stood out to both of us, independently, that weekend. It was essentially the same distress-sale thinking we had used to identify our very first deals at Lorenzo, Carney earlier in the decade.

At the time, National was one of the smallest of the country’s trunk carriers. Its routes essentially ran from Florida up the East Coast. It also had a southern extension from Florida to the West Coast, with a stop in Houston. The company had some routes to Europe, too. With its sleepy, conservative management, National seemed like a natural target for purchase. Never mind that its revenues were more than three times the size of ours or that it flew five times more revenue passenger miles (the number of miles traveled by paying passengers) than we did. The coming of deregulation called for a bold move, and this qualified as one.

As we saw it, National had great investment value. In addition, it complemented TIA. National had Florida; we had Texas; between us, we had two of the nation’s fastest-growing Sunbelt states. They had the brand name and financial resources; we had the management and energy. Even our fleets complemented each other. National had big 727s for medium- to long-haul flights, and we had the small planes, DC-9s, for feeder markets, which would be so important after deregulation. Our Houston hub could serve National’s route structure well, and indeed we had good connecting links already established in Houston. The two companies were a very good fit. In fact, I had attended a press briefing given by National in Houston at which its salesperson showed the company’s route map stretching across the country and up the East Coast, with Texas International connections in Houston shown clearly in dotted lines.

But best of all, National’s stock price, at around $18 per share, was extremely low compared to the net value of its equipment and holdings, which we figured could be as high as $75 per share. However, the $18 price at which the stock was trading was at a high for the previous twelve-month period—the low had been $9. In terms of financial strength, we saw National as though it were a little bank; it had a strong and clean balance sheet. Bob and I were very enthusiastic about the value and potential of the company.

Later that week, after Memorial Day, Sharon and I went up to Cambridge, Massachusetts, with Bob and his wife, Nancy, for our fifteenth Harvard Business School reunion. Bob and I had been in different sections at the school, so there were a lot of times when we were off at separate functions, but we were staying at the same hotel and had breakfast together in the mornings. Without fail, whenever we met, our conversation turned to National Airlines. We were both preoccupied by the opportunity. We attended one reception together, at a Boston art museum, and Bob and I kept scheming about National as we took in the collection. It was there, in that museum, that we decided to start buying National stock. Maybe there was a friendly deal to be done, but even without one, the stock seemed too great a bargain to pass up. And down the road, we wouldn’t rule out a hostile bid for the company.

So when we returned from Harvard, we called Smith Barney & Co., our broker, and quietly began buying the stock. Smith Barney arranged for the purchases to be made through its arbitrage department for maximum confidentiality. To disguise the trades, many were made through accounts at other brokerages. We wanted to make sure that the specialist who handled the stock at the stock exchange wouldn’t see the same name repeatedly buying the stock. The specialist was in reality a speculator focused on his own profitability in addition to being a market maker. If he sensed his stock was being accumulated, he would hold it in his own account, which would tend to lift the price, all things being equal. Bob and I were so conscious of leaks and disturbing the stock price that we didn’t even discuss our initial purchases with our directors.

We also commissioned Smith Barney to undertake a thorough study of the company so we could see what type of bid might make the most sense. In addition, I made a call to National’s chairman, L. B. “Bud” Maytag Jr. (a scion of the appliance family), whom I’d met several times at various industry functions, to see if a friendly meeting could be possible. After a few minutes of small talk about the latest deregulation news, we agreed to a lunch date in Miami for the following week. Two days later, though, Maytag’s secretary called to cancel. Over the following few weeks, I called Maytag several times to reschedule, but I never heard back from him. I’ve always suspected that his lawyers warned him that my call was probably about doing a deal and that if he wasn’t interested, he should keep his distance. That’s not the way I would have played it had I been in Maytag’s position, but I could certainly see their point of view.

Maytag’s brush-off didn’t bode well for our hopes for a friendly deal. But Bob and I decided to continue buying National stock anyway during June, by that point with our board members’ approval. Everyone agreed: even absent a deal, National stock was still too great a bargain to pass up. Down the road, we thought, if we accumulated enough stock, we could consider a hostile takeover of the company.

Back in 1978, leveraged buyouts and hostile takeovers of companies in general were still extremely rare, and none had ever been attempted in the staid, highly regulated airline industry. But we knew that deregulation was bound to disrupt the chummy fraternity of airline executives sooner or later. Perhaps, we thought, it might make sense for us to take the initiative and set a new course. The odds of gaining control of National were probably no better than one in five, but since our evaluation told us that the stock could be a winner, we saw limited downside risk in trying, or so we reasoned.

Arni Amster, the head of Smith Barney’s arbitrage unit, kept chipping away at the stock, buying up blocks in the tens of thousands, or just a few hundred shares at a time—whatever was available at a reasonable price. At the beginning of 1978, TIA had a net worth of $14 million, and the financing in April added $10 million. By the end of 1978, we would have nearly $60 million tied up in National, so it really was a huge gamble. Nevertheless, we proceeded with more optimism than caution, but probably just enough of each.

Around two weeks into our buying spree, I took a peculiar call from a Stanford University professor who claimed to be doing merger evaluation work for the Pan Am chairman, Brigadier General Bill Seawell, and said he was interested in pursuing discussions with TIA. So I called Seawell myself to see about his interest. I had gotten to know him at industry gatherings, and he probably viewed me as a kid running one of the ants of the business.

“What’s this I hear about your interest in TIA?” I asked.

“We have some interest, Frank, that’s true,” he said. “Maybe we should get together.”

We set up a drinks date for a few days later at the 21 Club in New York, in one of the quiet corners of the restaurant. It was the third week in June, and Bob and I were continuing to buy National stock, still without anyone noticing. Of course, there was no reason to inform Seawell of our expanding portfolio, certainly not until I heard what he had to say.

What he had to say was pretty much what I expected. Pan Am was indeed looking at several domestic carriers. Seawell seemed convinced that the way to ensure Pan Am’s survival in a deregulated marketplace was to acquire a stake in a domestic airline and use that national carrier to help feed Pan Am’s international routes. He and his people had done a preliminary evaluation of TIA and liked what they saw. His exact words were that TIA “looked decent,” which I took as high praise. “We’d like to look at it further, Frank,” he said, “but only if you have any interest.”

“Sure, we’re interested,” I allowed, even though in fact I was not. I didn’t really think Pan Am was such a logical suitor or that Seawell was all that serious in his pursuit, but I wasn’t about to close the door before I heard his offer. It made sense to keep talking and continue our National stock purchases.

On Thursday, June 29, just as Sharon and I were looking forward to a trip to London and a short vacation beginning the following Saturday, Amster called me, barely able to contain his enthusiasm. “There’s National stock all over the place this morning, Frank. We could do a cloudburst today.” This is an arbitrageur’s term for what happens when you buy such a large block of stock that you start to draw out anxious potential sellers. By that point, with our steady buying, we were about 100,000 shares short of the 4.9 percent ownership threshold that would require us to file a schedule 13D with the Securities and Exchange Commission, publicly declaring our holdings and our intentions.

We all expected that this day would probably come, but to be honest, I was caught unprepared. It was barely a month since Bob and I had hatched our National-buying plan at Harvard. Actually, to call it a plan was generous. All we were really doing was buying up some stock and buying time to figure out our next move. I wasn’t ready to go public with our efforts, although the regulations gave us a ten-day window in which to file our disclosure. Most buyers used the ten days to snap up even more stock before the disclosure would send the stock higher.

The common tactic, as Arni laid it out for us, was to fall just short of the 4.9 percent mark, then go over it in a big way. The large blocks at issue that Thursday would certainly put us over the 4.9 percent mark, but I wasn’t sure we wanted to buy through at that level just yet. From a strategic standpoint, I didn’t think we were ready to announce to the financial community, or to our employees, that we had taken such a large stake in National. And we weren’t ready for the public relations frenzy that would surely follow. Also, on a strictly personal level, it was important to me that word of our position wouldn’t hit the Street while Sharon and I were out of the country.

“Look, Arni,” I said when he called to tell me of the large block that had become available, “I just don’t think we should do this today. I want more time to think about it.”

“You’re making a big mistake, Frank,” he cautioned. “The market waits for no man.”

“I’m uncomfortable being out of the country when we have to file with the SEC,” I said.

“So change your plans,” Arni quite practically countered. “Today’s the day. You might not get another chance like this.”

I still wasn’t ready to take that last leap, but Arni felt so strongly about the opening that he came to our New York office later that morning to make a final pitch. In the end, he won me over. I quickly canvassed our executive committee for affirmation and gave Arni the go-ahead in time to make his big buy. And buy he did. By the time the market closed, we’d nearly doubled our holdings, buying close to 275,000 shares, most of it in two big blocks, at $17.375 per share. We learned later that our buying spree was fed by a stroke of luck: earlier that morning, Shearson, Hammill had downgraded its evaluation of National to “sell” based on an expected deterioration in earnings. (Without Bloomberg terminals and the technology we have today, we didn’t learn of the Shearson sell alert until the next day.) After the sell call, the institutional investors holding large blocks of National stock were suddenly eager to unload their shares, and we were there to take them off their hands. National was one of the most active stocks on the New York Stock Exchange that day as a direct result of our cloudburst, and the Wall Street Journal reported the next morning that National did not know of any reason for its stock’s level of activity.

By coincidence, earlier in the spring, Sharon and I, along with a number of Houston dignitaries, had been invited on the maiden flight of Pan Am’s Houston–London route. We didn’t normally travel in such rarefied circles, but Pan Am was counting on TIA to provide feed traffic for the new service by virtue of our modest (at the time) Houston hub, so we were invited on the flight and to the inaugural celebration in London over the July Fourth weekend. This was the origin of our vacation plans.

While in London, the Pan Am guests were feted in a grand manner. We were all put up at the plush InterContinental Hotel, which the airline owned at the time, and there were several receptions held to commemorate the occasion. On Tuesday, July 4, there was a formal dinner to cap off the festivities, and before the meal I sought out Seawell and asked if he could carve out some time the following morning. As a courtesy, I thought I’d let him know about our National shares, given his expressed interest in pursuing a deal and given that we would be on the short vacation we had planned in Switzerland over the coming weekend, which would also coincide with our public disclosure the following Monday.

We arranged to meet the next morning after breakfast, although we were more tired than expected. At four o’clock that morning, there was a fire in the hotel kitchen, and the building was evacuated. Imagine the scene outside the hotel: all Seawell’s guests, including the mayor of Houston and other dignitaries, piling into the street—half asleep, half dressed—some of them carrying books or briefcases or handbags, whatever was important to them. General Seawell paced in front of the building in his robe and pajamas, huffing about the indignity of the fire, making frantic apologies. He seemed embarrassed to the point of tears that a freak kitchen fire should upset his distinguished guests on the last night of such an important occasion.

But we were all back in our rooms a short time later with our valuables in tow and a story to tell for years afterward. I went up to meet Seawell in his suite later that morning as planned and dropped my bombshell: “General,” I said, “I know you’re going to be out of the country for a while, and I wanted to let you know that we’re going to announce on Monday that we bought some National Airlines shares.”

There was no immediate response, and when I looked up, I saw a blank gaze on Seawell’s face. He seemed thrown for just a moment, but then he collected himself. “Really?” he said, perking up. “That’s great. I’ve been thinking about doing the same thing, but I could never get our board to approve it.” I felt it was important that Seawell hear this piece of news from me, on a confidential basis, not only in consideration of his interest in our company but also out of respect for a man who had been very gentlemanly to me. I also used the opportunity to discuss the opening of the new Terminal C at the Houston airport and how Pan Am and TIA would fit into the plans for it. But this subject, however important, seemed decidedly minor to Seawell in comparison to the news about National.

With my personal obligations to Seawell out of the way, Sharon and I took off for Geneva later that afternoon to begin our relaxing drive across Switzerland. We took a few days getting from Geneva to Zurich, arriving as scheduled the following Monday and checking into the beautiful Dolder Grand hotel, located in the hills just outside the city. This hotel had been a favorite of mine since my first stay there, with my parents back in 1955. We dropped our bags in our room and immediately went to the local Smith Barney office. It was nearly three o’clock in the afternoon in Zurich, nine o’clock in the morning in New York, and I wanted to see how the market would respond to our announcement—planned, coincidentally, for that time.

I couldn’t have timed it better if I had been a choreographer. Sharon and I walked into the brokerage office almost the moment the news came across the Dow Jones broad tape: “Texas International announces 9.2 percent ownership of National Airlines.” The account reported that we had paid a total of $14.35 million for our shares and said that TIA was “considering the possibility” of seeking control of the Miami-based company.

I was, frankly, a little nervous now that the veil of secrecy had been lifted. We were out in the open and still not entirely sure of our next move. I knew we would make news, but I didn’t fully realize what an explosive piece of news it was. The brokers in the Zurich office, who didn’t know who we were, buzzed with the story. We later learned that the market had the same general reaction: “Texas who?”

The reports that came across the tape throughout the day all noted our size. One analyst likened our move to “a rabbit trying to buy an elephant for a pet.” Another called us “a sardine chasing a shark.” A UPI wire story referred to the filing as “a frog-that-swallowed-a-whale merger attempt.” And Barron’s columnist Alan Abelson, avoiding these animal kingdom metaphors entirely, simply gave us his “chutzpah of the year award.” In newspaper accounts, we were painted as pesky little guys looking to topple one of the industry’s big boys on the eve of deregulation.

The market responded in kind: National shares jumped 25 percent, to $22, by the closing bell, while our own stock climbed sixty-two cents to close at $12. Almost immediately, there was wide speculation that other suitors were readying their own bids for the company; Braniff’s name was among those bandied about, and Pan Am’s surfaced as well. By the end of the month, National stock was trading at more than $26 per share, while TIA had climbed to more than $14.50 per share, up more than 25 percent from its price before the announcement. (It was, and remains, unusual for shares in an acquiring company to rise in a takeover bid, and the fact that ours did most likely reflected the Street’s view that we were making an attractive move—and, of course, that we were already registering a substantial paper profit on our stock holding.)

Meanwhile, with the price of National shares soaring, we were no longer sure which way we wanted to go. On its face, our investment was paying off, but the full-scale acquisition that looked extremely attractive at the $20 level was suddenly looking a lot more expensive with the stock nearing $30. With commitments to spend another $70 million on eight new DC-9s by the end of 1979, I wasn’t exactly confident that we could raise enough money to finance a takeover.

A provision of the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 stipulated that owners of 10 percent or more of an airline’s stock were “presumed to be in control” of that airline. Consequently, because we wanted to be able to continue buying, we had to act quickly. On Friday, July 28, with the dust still unsettled and our course unclear, we made a formal application to the CAB to acquire control of National Airlines, prompting National’s board to convene an emergency meeting that weekend to review the matter. Even after nearly three weeks, the National board had given no formal response to our filing and from all appearances seemed to be either still reeling from our initial announcement or just feeling like a fly had landed on an aircraft and needn’t be dealt with.

In our CAB application, we pledged to place our current and future National holdings in a voting trust, voting proportionally with other shareholders in any action, enabling us to expand our stake in the company beyond the 10 percent level used by the board to determine controlling interest. Our intention, we stated, was to avoid any controversy on the issue of control while continuing to acquire shares up to the 25 percent ownership level established by the CAB on pending mergers. At that point, we would suspend our buying program until we had a final ruling and until we had completed a merger agreement with the National board. The 25 percent level, we figured, would be more than enough to give us working control of the company, if approved. To seek any more, we feared, would jeopardize our chances with the CAB. Of course, as we explained, we were also taking the risk that if the board turned us down, we’d have to sell our shares, probably taking a big loss.

Our filing defended our acquisition of National shares and our desire to buy more: “[Texas International] saw an investment opportunity and made what it considers to be a prudent and lawful commitment of its capital. There must be room in this industry, as there is in unregulated industries, for free management choices of this type. Such a free climate in the capital markets goes hand in hand with the board’s encouragement of a more competitive operating environment.”

It continued, “Undoubtedly, opponents of the acquisition will contend that Texas International has acquired control of National without prior board approval. They will insist that Texas International dispose of the stock acquired so far before the board considers the transaction on its merits. But acceptance of that approach would represent a return to the old, protective approach toward the industry.”

With the market price of National continuing to climb and trading levels shooting higher amid rumors of interest from other airlines, particularly Braniff and Pan Am, we were eager to continue to purchase the stock. We really thought the CAB would understand the marketplace consideration and the consequences of denying us the ability to buy more of National. We were taking the risk essentially without any voting rights.

On the very afternoon of the filing, the CAB responded with a formal warning that our plans might have constituted a “knowing and willful violation of FAA regulations,” which made it unlawful for one airline to enter an “interlocking relationship” with another without first obtaining CAB approval. John Golden, deputy director of the CAB’s bureau of compliance and consumer protection, further cautioned that if we continued to purchase National shares before the board made its ruling on the matter, we would be subject to civil penalties or other disciplinary action.

We were treading on new ground with the CAB in creating a type of trust that had never been done before. But I thought it was critical to have this ability to go to 25 percent, thus pushing the envelope. The trust arrangement to buy stock was a good gambit—our only one, it seemed. I knew that if we waited to buy more stock until the final CAB ruling, likely many months later, we would risk losing the deal entirely. The stock was now in play, and bigger airlines could push the price out of our reach if we had no opportunity to add to our position. In our filing creating the trust, at least we wouldn’t lose any ground waiting for the final CAB action. If the board ultimately rejected our proposal, then we would be forced to sell the stock out of the trust; but if it approved our bid, as we fully expected, then we would have kept our advantage over the other suitors.

As National shares headed still higher, it was clear that we would have to replenish our war chest if we hoped to secure a toehold. We had sunk most of our new working capital into National, and there was still a long way to go, so we looked to the European financial community for some quick financing—a Eurodollar deal, as they were called. In those days, it was much easier to raise money overseas than it was at home: you could simply prepare a prospectus, visit investors, offer the securities, and close the deal within a few days without the volumes of paperwork or the long waiting periods required by the SEC on transactions in the United States. At the time, however, no American airline had ever arranged European financing, so this, too, was new territory.

Our investment bankers arranged a five-day “road show” to London, Paris, Geneva, Zurich, and Frankfurt, and I pitched our offering of convertible subordinated debentures at fancy lunch and dinner gatherings at each stop. At the time, oil was a very hot commodity, and the image of the Texas oilman had become a global symbol of wealth and largesse. All our potential investors wanted to hear about was Texas, Texas, Texas, so I gamely played up that image wherever possible. I did everything short of donning a ten-gallon hat and telling these European moneymen that there was oil underneath our runways.

The overseas offering was a quick sellout, raising $25 million in 7.5 percent convertible subordinated debentures, and we returned home rearmed for our run at National. But while we were off raising money, Bud Maytag finally mounted his counterattack. On Tuesday, August 8, National urged federal officials to block our takeover bid on the grounds that we had violated the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 and various antitrust laws.

National also complained to the SEC, alleging that our April financing failed to disclose an intent to acquire National in the “use-of-proceeds” section. This allegation prompted the SEC to investigate us for months, but these charges were eventually deemed without merit, as was National’s subsequent effort to prove that our European financing left us in potential violation of a federal law restricting foreign ownership of domestic carriers. National also aimed its legal guns at Jet Capital, the holding company that controlled TIA, arguing to the SEC that Jet was an investment company and required to register, which for an operating company is a very bad turn, imposing extensive regulation, operating limitations, and added cost. This charge was also dismissed by the SEC. Maytag and company had a bagful of harassment tactics, and when one failed, they reached in for another. They succeeded in spinning our wheels, spending our money, and redirecting our attention, but we pressed on.

Finally, at an August 17 CAB “sunshine” hearing to consider our bid—so called because formal CAB meetings were required to be conducted in open forums—the board voted to issue an order allowing us to proceed with our purchase plans while continuing its full investigation of the matter. In an unprecedented ruling, the CAB chairman, Alfred E. Kahn, held that our buying did not violate the Federal Aviation Act and that we could continue acquiring shares of National stock subject to formal approval, which could come as late as March 1979. If the board ruled the arrangement unacceptable at that time, we would be forced to divest ourselves of the newly acquired stock—which was understood.

With Kahn’s ruling, we moved on to buying more stock right away—sooner, in fact, than we should have. Arni Amster had been champing at the bit, watching National shares climb to the $30 level in the weeks following our disclosure, and the stock was particularly active on the afternoon of the CAB sunshine meeting, when it appeared that there was another large buyer in the market. After I walked out of the meeting, I phoned Arni and told him to resume buying, even though I wasn’t all that comfortable at these high levels. At $30 per share, we were showing a $7 million paper profit—not bad for two months’ work—and here we were sticking our necks out even further. But I knew we had to protect our position, particularly if we were headed for an auction. I also knew that the longer we waited, the more we’d have to pay to stay in the game.

We ran into some trouble at that point, but not a lot. Shortly after we disclosed these added purchases, in yet another effort to block our bid, National accused us of jumping the gun on our stock purchases immediately following the CAB meeting. Technically, they were right. We were jumping the gun by a few days. Although Kahn had verbally approved our application to place additional shares in a voting trust, it would be a week or so before we had the formal paper document officially sanctioning our continued buying. We were guilty according to the letter of the law, but the board held that our infraction was not malicious and assessed only a token fine—a small price to pay given the substantial amount of stock we accumulated in the intervening period and the subsequent jump in price.

On August 23, four trading days after the sunshine meeting, the other buyer surfaced: Pan Am announced that it had amassed a 4.8 percent stake and was offering $300 million to buy National—or $35 per share. The bid, which confirmed that Seawell had finally gotten his board to act, would have merged the two companies into one of the world’s largest airlines. From TIA’s perspective, it would have sent any competing offer for National into the stratosphere cost-wise.

The news set off a flurry of activity in the market and made us rethink our strategy. At $35 per share, our interest in acquiring the airline was lukewarm at best; it would be a tough price to justify to our shareholders. But we never had to make that decision, because the market pushed the stock right through the $35 level almost immediately. At $40, which was where the stock was quickly heading, the price was way beyond the point where a deal for us made sense. Believe it or not, Bob Carney and I tended to have a conservative streak, so we did an about-face on strategy and started thinking of ways to maximize our profit on the deal rather than how to acquire the company.

Within a week of Pan Am’s offer, we backed off thinking of ourselves as buyers and focused even more on thinking of ourselves as sellers. But even though we were then looking at National as a pure stock play, we weren’t about to let on that our goals had changed. It was in our interest to publicly pursue the deal and keep pushing the stock. In late August, Pan Am and National agreed on a merger at $39 per share, up from the $35 offer. Shortly thereafter, on August 29, to pressure National and Pan Am to up the price of their merger beyond $39 since the stock was already trading over that price, we swallowed hard and bought 320,000 shares at $40—a $12.8 million purchase, easily eating up most of our recent financing in a couple of hours. I’ll confess I didn’t sleep too easily that night.

Two days later, Pan Am and National raised the merger price from $39 to $41 per share, and we were still in the picture. In fact, the news accounts from that period—and this was a big deal, so there were a whole lot of news accounts—all mentioned that TIA had yet to make a formal offer for National. This was true, and there was none forthcoming. In one interview, I allowed that we had no specific plan for a takeover. “We don’t have one in writing,” I said. “We don’t even have one on the back burner.”

Still, there was wide speculation about our next move, and even while Pan Am and National came to a final agreement on September 7, the market seemed to be waiting for the other shoe to drop.

Bud Maytag continued to dodge my calls. The only communication we had during the late summer and early fall was in a series of open letters from Maytag (really, of course, from his lawyers and investment bankers) to our board of directors. “At this point,” Maytag wrote in one letter, dated September 25 and released to the press before it arrived in our offices, “we can only conclude that Texas International has embarked on a venture it can’t finish—one that is not in the best interest of its fellow National shareholders. In effect, [TIA] wants to fly now so all the rest of National’s shareholders can pay later.”

The tone, like that of all Maytag’s public missives, was challenging and hostile, although I couldn’t read them without also hearing the uncertainties and misgivings of a man whose company had somehow gotten away from him. By mid-September, Pan Am’s stake in National had grown to 18.1 percent, TIA held 20.1 percent, and both airlines had applications for control pending with the CAB, although unlike Pan Am, we had not filed for any merger approval. Maytag appeared in the torrent of press accounts as a stumbling corporate figurehead, clearly bound for the door; the only question that remained was which exit he’d be forced to take.

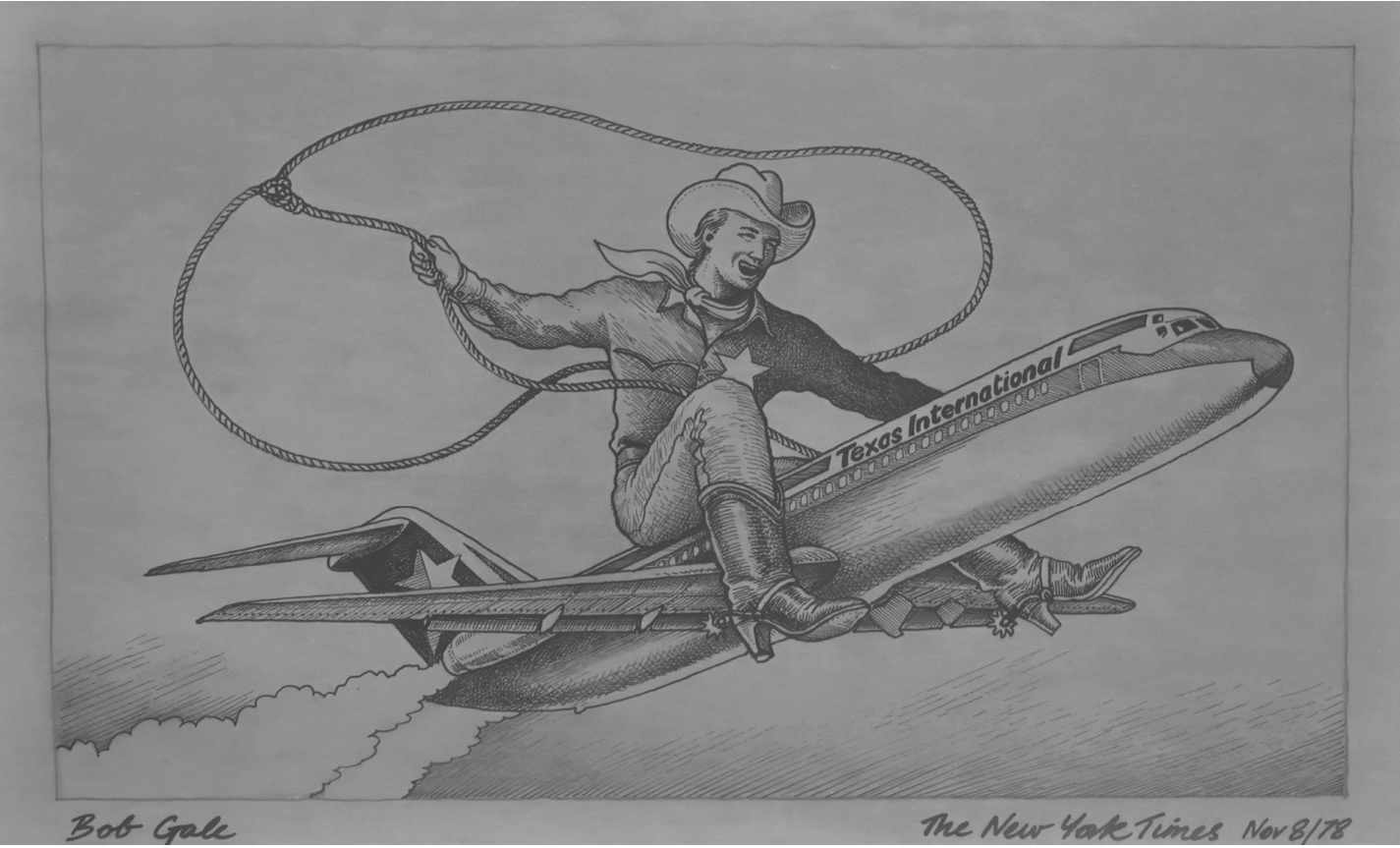

Bob Carney and I came off looking like a couple of feisty, visionary thirty-eight-year-old upstarts, an obvious exaggeration or possible untruth, but we weren’t about to quibble. Forbes ran a piece in October 1978 titled “Lorenzo the Presumptuous,” in which I was dubbed a “Goliath-baiter” and TIA was hailed as one of the industry’s “most innovative companies.” Considering the competition in those regulated days, the bar was not very high. In another account, I was quoted as saying that acquiring National would cost $32 million less than buying a “modest” fleet of ten Boeing 727-200 jets and spares (support equipment and services)—a rather brazen comparison, it seems to me now. And the New York Times, in an article titled “No Longer Tree-Top Airways,”2 called our bid “a mouse-that-roared strategy that raised eyebrows both in the industry and on Wall Street.”

New York Times cartoon showing TXI bid to acquire National Airlines (1978).

In October, we still had some buying room from the CAB order, but then we were looking at suddenly reduced prices in National stock. Just as the overall market entered a period of sharp contraction, and with National’s future and the CAB decision still up in the air, the price of its shares took a surprising nosedive, to the $25 level. Investors were doubting whether any deal would win CAB approval. But we held on to our game plan, and on October 17 snapped up another 174,200 shares at $25.875.

This last block brought our holdings to 1,892,500 shares, or 22.1 percent of the company, for a total cost of $52.3 million, which actually meant that we were showing an overall loss of just over $2 million. Nevertheless, we continued “buying the stock down” over the next several days, confident that the price would eventually return to its previous much higher levels.

Beginning in November, Pan Am began racking up a series of civic endorsements in support of its control-merger proposal. New York City officials testified on Pan Am’s behalf before the CAB, the Miami-Dade board of county commissioners voted 4–2 in favor of Pan Am’s application, and the Florida cabinet passed a resolution supporting a National–Pan Am merger. We countered with the unsolicited endorsement of Alfred Kahn, freshly retired from the CAB, who stated publicly that a National merger with TIA would be better for the industry and the flying public than a union with Pan Am. Even out of office, Dr. Kahn was a great champion of deregulation and competition, and he had some difficulty hiding his strong beliefs, whether or not his comments were appropriate.

Then in December, the playing field changed. Unaware of these next developments, I was in Washington on Thursday, December 7, 1978, for a meeting of the Air Transport Association. These gatherings were always a good place to canvass the industry on matters of mutual interest, and at this event, the pending National deal was a major topic of conversation. Strangely, I was even questioned about the deal by a colleague from my early days at Eastern, Charlie Simon, who was Eastern’s chief financial officer. What struck me as peculiar about Charlie’s interest was where we were at the time: in the men’s room, at adjacent urinals.

Now, Charlie was a very discreet guy, his choice of meeting places notwithstanding, and I’m confident he would not have asked me about our National deal if he’d known that his boss, the Eastern chairman, Frank Borman, was mounting a bid. Borman, who had publicly opposed Pan Am’s bid and vowed to fight its merger with National on antitrust grounds, spent the following weekend huddled in Miami with his board and his lawyers, preparing yet another offer for National on his own. On December 6, the day before, the National president, E. F. Dolansky, had testified before the CAB that the airline was still open to offers that might exceed Pan Am’s, which stood at $41 per share, and Borman must have seen this as his last chance to get in on the bidding.

On Monday morning, December 11, I took a courtesy call from Borman, who wanted to let me know that the announcement of an Eastern offer for National, at $50 per share, would be crossing the tape in a few minutes. I was ecstatic that there would be a third bidder for the airline, but of course I kept my reaction to myself. In Borman’s mind, at least, we were still competing on the deal, and he had just upped the ante by $77 million. Bill Seawell, I later learned, wasn’t quite so cool about keeping his emotions under wraps; when Borman made a similar courtesy call to him, the general apparently hit the roof.

“It’s a new ball game,” Borman later told reporters. Indeed, it was.

The move took us all by surprise. In a proposal to the CAB, filed concurrently with his bid to the National board, Borman asked that Eastern’s offer be considered on the same timetable as TIA’s and Pan Am’s, claiming that an Eastern–National merger would “promote competition, especially across the Atlantic.” This last claim played to the new pro-competition bias of regulators, although it struck me as somewhat unfounded. There was no masking the fact that there was a great deal of overlap between Eastern and National on some very major routes, and on antitrust grounds alone, it seemed doubtful that Borman’s bid would pass muster.

Many airline and market analysts viewed the Eastern bid as a purely defensive move made in order to upset a planned January 15, 1979, meeting of National shareholders at which they would vote on the Pan Am deal, although some also recognized the value of National’s newly granted London, Paris, Frankfurt, and Amsterdam routes to Eastern’s plans for international expansion.

We could not have cared less about Borman’s motives or his chances. What we liked about this latest development was the prospect of yet another run-up in the price of National stock. But unfortunately, Borman’s offer didn’t spur a whole lot of movement in the stock (Eastern wasn’t buying until it had a favorable ruling from the CAB). National continued to trade in the $36–$40 range in the weeks following Eastern’s bid, which we took to mean that the arbitrageurs, who by then owned most of the non–Pan Am and non-TIA stock (around 50 percent of the shares), didn’t think Borman stood much of a chance.

On Monday, January 22, the Justice Department officially opposed the efforts of Pan Am and TIA, even though the CAB had not ruled on either merger. The assistant attorney general, John Shenefield, claimed that the proposed mergers were anticompetitive and would likely hurt consumers as a shrinking number of major airlines tightened their grip on pricing practices.

The Justice Department rejection was a setback and sent National shares swooning, but I don’t think any of the parties looked on it as a major blow because the CAB had the final say. Still, the very public objection to our actions put us all back on the front pages, and even on some prominent editorial pages, the following morning.

The Washington Post, in an editorial, urged the CAB to ignore the Justice Department and allow the free market (and National’s stockholders) to determine the outcome. “While such a decision could spur more merger proposals,” the Post editorial read, “it would be in keeping with the spirit of deregulation. A decision blocking either or both of these takeover bids would suggest the government is not yet ready to let go of the regulatory reins it has kept on the airline industry much too long.”3

Finally, after nine months in the game, we decided to make our first formal offer to acquire National Airlines. Up until this time, all we had done was amass a 24 percent ownership position in the company with no specific takeover plan. We’d taken a great deal of heat for our sit-back-and-wait strategy, but it made sense for us to conceal our hand. At that point, though, we wanted to put some additional substance behind Eastern’s offer price (especially since the arbitrageurs were dubious of the Eastern offer), and the way to do this, it seemed, was by making a conventional bid of our own, as best we could.

On Tuesday, February 20, we matched Eastern’s $50 bid, with a per-share offer of $8 in cash, one share of TIA stock (which was trading at around $12), and various debt securities. Ours was almost entirely a “paper” deal, and we never expected National to bite on it. At these high prices, we weren’t really trying to buy the company so much as we were trying to push the Pan Am deal price up to Eastern’s $50 level. Certainly there was always the chance that National would accept our offer, and we would have to “eat” the deal. In order to protect ourselves from this long shot, we had to make sure our proposal was structured in such a way that it was credible and we could live with it if it went through. This ($8 in cash and $42 in equity and debt securities) was a deal we could live with.

Predictably, National wanted no part of our proposal, so we nearly doubled the cash component of our offer in the ensuing days, but they turned us down again. In addition to sweetening the deal, we also inched closer to the 25 percent ceiling established by the CAB, grabbing another 121,000 shares of National stock on March 14 (at an average price of $40.41) and bringing our stake to 2.1 million shares, at a total cost of approximately $59.2 million. It was like a high-stakes poker game, and we were determined to stay in the bidding until the very end.

We added to our treasury at this time by completing one of our most interesting financings. We still had seven new DC-9s on order from McDonnell Douglas and had completed a major deal with Swissair to buy twenty used DC-9s over the course of a couple of years, in addition to the possible National needs. As a consequence, on April 11, we closed on $35 million of guaranteed floating rate notes due in 1986 in the Eurodollar market. I should point out that the very somber “guaranteed” was that of TIA, not of some staid financial institution, as was often the case.

A funny background to this financing: in early March, I had a meeting with an investment banker in New York who mentioned that Citibank had just completed an offering of Eurodollar floating rate notes with interest at 1 percent over the so-called LIBOR—or London interbank offered rate. Given the quite high profile of TIA at the time, certainly in Europe, I inquired whether we could sell a similar security, adding a few points more in interest. The banker came back a few days later, after checking with his London office, and said that while that type of offering was normally only done by major institutions, they were willing to give it a try. Thus was born our floating rates deal, and we got our money in three weeks, thanks to the simplicity of the Eurodollar market in those days.

The administrative law judge in our and Pan Am’s control case delivered his opinion on April 5, calling on the CAB to reject our bids. Naturally this news was unsettling, but we were prepared for it, because law judges were often centuries behind the real world and we were confident that the full CAB would see it differently. The CAB immediately announced that it would take up an expedited review and not let the law judge decision stand as the final word.

On April 25, the Justice Department and the Department of Transportation finally checked in with their rulings on Eastern’s application to buy National, declaring in separate filings to the CAB that such an acquisition would violate both antitrust and aviation laws. Eastern was still in the game, pending the CAB decision on the matter, but that now appeared unlikely.

In April, Pan Am raised its bid yet again—to the $50 level previously offered by TIA and Eastern. Naturally, we were ecstatic.

On Tuesday, July 10, 1979, the CAB finally ruled on the National situation, unanimously approving our proposal along with Pan Am’s and rejecting the law judge–recommended decision—ironically, a full year after our filing of schedule 13D, which disclosed our National stock purchases. Publicly, I expressed disappointment that Pan Am was deemed an acceptable partner and allowed to remain in the running alongside TIA. Privately, I was thrilled: with Pan Am being granted government clearance to complete its merger, I knew there’d be a ready buyer for our 2.1 million shares—maybe the only buyer.

National stock, which had been hovering around $40 prior to the CAB decision, shot to $46 when trading resumed Wednesday morning. It was clear to Bob Carney and me that the time had come to fold our hand. After a call from Bill Seawell in which he asked to buy our shares in order to strengthen his position against a higher Eastern bid, we agreed to sell.

We announced the final deal with Pan Am on July 28, and it provided for the immediate sale of our initial 790,700 shares at $50 per share and the later sale of our remaining 1,309,300 shares on the same terms by the end of the year. The staggered buyout was structured to allow TIA to realize the capital-gains tax advantages for the National shares we had held less than the required one year. In the interim, we pledged to withdraw our April 12 offer to merge with National and agreed not to purchase any additional shares or to sell out to any other party. In total, we received $105 million (about $449 million in 2024 dollars) from Pan Am—a $46 million profit (about $197 million in 2024 dollars).

Combined with our three financings over the course of the nearly twelve previous months, we’d be sitting with nearly $125 million in reserves ($534 million in 2024 dollars)—a fantastic amount, considering our small size and our $14 million net worth eighteen months earlier. The real beauty of the deal for us was that we kept all the cash, although we had to pay taxes on the gain. Had we bought the stock on margin, or secured by a bank loan, we would have had to repay the debt on sale. Therefore, since we borrowed on an unsecured basis, we were able to put the sale proceeds directly into our treasury.

Word on the Street had us immediately going after another airline, but that wasn’t our plan, although we were diligently analyzing several prospects. We were flush with cash and ready to grow in the new challenging deregulated environment.

2 New York Times, November 8, 1978.

3 Washington Post, January 22, 1979.