Southern Foodways in the Nineteenth Century

By the nineteenth century, the invention of the cotton gin and steam-powered cotton textile mills had revolutionized the North American South. In the now-independent United States, cotton emerged as the premier cash crop. By 1811 the cotton gin had expedited the processing of cotton, which led to more cotton being planted, which in turn required more slaves to tend and harvest it. As a result enslaved African labor gradually dominated the South, creating a belt of territory where blacks made up the majority of the population. The industrial revolution and the invention of the steam engine increased travel throughout the new republic. Much of what we know about African American eating traditions in the nineteenth-century black belt comes from people who crisscrossed the region on steamships and trains. The Virginia, Georgia, Alabama, and Carolina regions, though each unique, were united in their cuisines through the use of three main food sources: pork, greens, and cornmeal. Two further habits also connected the different regions: the cooking of poor-quality meats for a long time to break down the connective tissue and the use of salt pork to season fibrous greens, which required extensive cooking to make them tender and easy to digest.

In plantation regions, argues one historian, enslaved Africans “had quietly been making a life for themselves that included a healthy concern with cooking.”1 This endured despite the fact that masters generally distributed stingy allotments of rations. To supplement their meals, slaves in lowland South Carolina worked under the task system, which permitted them larger amounts of time to cultivate gardens and raise domestic animals. We already know that, in South Carolina, planters gave their slaves rice as a part of their food rations. For instance, in the 1850s Frederick Law Olmsted visited several rice plantations in lowland South Carolina. Planters there gave their slaves rice as part of their food rations during the rice harvest and on holidays. Olmsted observed that planters gave “the cracked and inferior rice that would be unmerchantable” to the slaves as rations.2 In addition to rice, enslaved Africans received corn and sweet potatoes, “with the occasional addition of a little meat.” Slaves in Charleston, South Carolina, recalled traveler Adam Hodgson, “prepare for themselves a little supper from the produce of their garden, and fish which they catch in the river.”3

The Swedish novelist Fredrika Bremer had an opportunity to try some slave cooking on a Charleston rice plantation. While roaming near the rice fields one morning she spotted “a number of copper vessels, each covered with a lid, from twenty-five to thirty in number.” The plantation cook had filled each vessel with “steaming food, which smelled very good. Some of them were filled with brown beans, others with maize pancakes,” writes Bremer. “I waited till [the slaves] came up, and then asked permission to taste their food, and I must confess that I have seldom tasted better or more savory viands.” As the slaves came from the fields, each one sat down and ate, “some with spoons, others with splinters of wood. . . and each contained an abundant portion.”4 African Americans adapted pancakes from the Dutch. The Dutch traditionally made them from wheat flour, while southern African Americans used cornmeal to make hoecakes.

In the 1850s, Olmsted observed slave cooks in action on a large tobacco plantation further north, in Petersburg, Virginia. After an eleven-hour workday, slaves on the Gillin plantation returned to their quarters, where they cooked their own suppers. This tended to be “a bit of bacon fried, often with eggs, corn-bread baked in the spider [a frying pan with legs or feet on the hearth] after the bacon, to absorb the fat, and perhaps some sweet potatoes roasted in the ashes.”5

In the nineteenth century, African-American cooks continued to grow and cook with yams and sweet potatoes. They used these staples like bread, just as their descendents had done in West Africa.6 By the mid-nineteenth century, slaves in Virginia had influenced their masters to eat the tubers the same way. By the eve of the Civil War, African American cooks in South Carolina and Virginia had retained many African eating traditions and created new ones. Whites who lived and worked in close proximity to enslaved African Americans typically ate these same cheap, delicious, and filling dishes.7 From the British African Americans acquired a taste for and the ability to make pies and puddings, which they made with both the African yam and the American sweet potato.8 They also took pie making to another level with the baking of fruit cobblers from cast-off and foraged fruit and scraps of dough leftover from pie making done in the big-house kitchen.

SPECIAL OCCASIONS DURING SLAVERY

As slaves, African Americans only gorged on large amounts of meat and splurged on rich desserts on a few holidays and religious days during the year. For African Americans, then, good eating became associated with harvest feasts, Christmas, New Year’s, the Fourth of July, religious revivals, and Sundays (their only day off during the week). On these special days, slaves received time to cook and garden, extra rations, and access to sweets. Most enslaved African Americans ate much smaller portions and very little meat during the week and did hard physical labor from dawn until dusk six days out of seven in extremely hot weather. Obesity thus was not the problem it is among African Americans today. The correlation between food traditions and religious events dating back to the antebellum period explains why spirituality is also associated with making soul food.

Like their West African ancestors, enslaved African Americans made special foods a part of their religious activities. The function of food at religious assemblies represents an important continuity between West African and African American religions. In the Americas, enslaved Africans continued to use sacred foods such as chicken as they adapted to the rudiments of New World Christianity in the South. African and southern American religious events, with their singing and abundance of food, played an important role in shaping African American religious tradition and the development of soul ideology.

Africans learned Christian theology not only from the preachers that masters hired but also from enslaved licensed and unlicensed preachers and exhorters. Peter Randolph, a slave in Prince George County, Virginia, recalled that, “Not being allowed to hold meetings on the plantation,” unauthorized African American preachers would assemble “slaves in the swamps, out of reach of the patrols. They had an understanding among themselves as to the time and place of getting together.”9 Although the core of the enslaved Africans’ religious activity took place in private in the slave quarters, praying grounds, and hush harbors (a place where slaves secretly met to practice their religion), public gatherings such as Sunday church services and revivals were also very important.10

It was not uncommon for masters to give their slaves permission and support to attend organized religious meetings such as Sunday church services and revivals. Annual revival meetings, which the Baptists called “protracted meetings” and the Methodists called “camp meetings,” were morally sanctioned religious events that provided opportunities for all southerners to socialize, gather news, worship the Lord, evangelize, and feast. Church picnics and all-day preaching and dinner on the grounds became traditions basic to southern churchgoers, as most African Americans were by the mid-nineteenth century.11 “By the eve of the Civil War,” writes a preeminent historian of African American religious traditions, “Christianity had pervaded the slave community.” He adds: “The vast majority of slaves were American-born, and the cultural and linguistic barriers which had impeded the evangelization of earlier generations of African-born slaves were generally no longer a problem. The widespread opposition of the planters to the catechizing of slaves had been largely dissipated by the efforts of the churches and missionaries of the South. Not all slaves were Christian, nor were all those who accepted Christianity members of a church, but the doctrines, symbols, and vision of life preached by Christianity were familiar to most.”12

Religious workers regularly organized weeklong revivals that were often interracial, communitywide events. Fredrika Bremer described a camp meeting revival she observed during a visit to Macon, Georgia, in May 1850. “After supper I went to look around, and was astonished by a spectacle that I shall never forget. . . . An immense crowd was assembled, certainly from three to four thousand persons. They sang hymns—superb choir! Strongest of all was the singing of the black portion of the assembly, as they were three times as many as the whites.”13

At sunrise, Bremer woke to the delightful sound of African Americans singing hymns and the delicious smell of frying ham and eggs, simmering red-eye gravy, steaming rice or grits, and baking buttermilk biscuits and corn bread. “People were cooking and having breakfast by the fires, and a crowd was already” gathering and filling the benches under the tabernacle for the seven o’clock morning worship service and the eleven o’clock sermon that would follow. “After the service came the dinner hour, when I visited several tents in the black camp, and saw tables covered with all kinds of meat, puddings, and tarts; there seemed to be a regular superfluity of food and drink.”14 Bremer’s description of this Georgia camp meeting is reminiscent of travelers’ descriptions of singing and feasting during West African religious gatherings, discussed earlier.

In some parts of the South before emancipation, the Church was the only institution in which whites permitted African American southerners to maintain their own peculiar way of satisfying their souls and bodies with spiritual and natural food. The autonomy of African American religious churches in the South naturally increased with the abolition of slavery. Moreover, the use of churches for community events drastically increased. Freedom for many African American southerners meant more time for church events like revivals and allowed for the addition of new events to a church’s yearly activity calendar, such as Emancipation Day celebrations. But descriptions of Christmas feasts indicate that it was the most lavish of the yearly food-accompanying celebrations.

“Sundays and revival meetings,” writes a historian of African American religion, “were not the only respites from work anticipated by the slaves. Christmas was the most festive holiday of all.”15 Masters generally granted slaves the week of Christmas off and gave those who wished it permission to visit nearby plantations where friends and relatives lived. They also furnished slaves with additional bacon and cornmeal rations, as well as flour and fruit for making biscuits, preserves, tarts, and pies.16 Additional rations distributed for Christmas and time off from the fields allowed women to cook delicious dishes like ribs, hams, chops, chitlins, stews, soups, and sauces for their families and friends.17

Soul—Africanisms, spirituality, southern style, pride, love, care, and joyous hard work—cannot be understood without taking into consideration southern American religious rituals and oral traditions. During slavery, members of plantation communities brought the best of their first fruits and dishes to share with friends, family, and visitors. In the South, the most important religious celebrations coincided with the end of the harvest, when communities had an abundance of food and leisure time.

During slavery, foods cooked on Sundays and special occasions played an important role in southern African American religious traditions. Most slaves considered Sunday special because they could visit kinfolk on different plantations and make special meals that expressed their love for family and friends. Oral traditions allowed them to pass down instructions to the next generation on the intricate preparation of foods eaten on religious days: fried chicken, barbecued beef and pork, biscuits, pies, and cakes.

SHARED CULINARY TRADITIONS BETWEEN AFRICANS AND EUROPEANS

Enslaved Africans did not develop their traditions within a vacuum. In some instances, whites, particularly white children, had intimate relations with blacks. Through close interaction, whites integrated many African religious and language elements. “Southern whites,” argues historian John W. Blassingame, “not only adapted their language and religion to that of the slaves but also adapted agricultural practices, sexual attitudes, rhythm of life, architecture, food and social relations to African practices.”18 As masters adopted African foodways and slaves adopted the holidays and special occasions of their owners, black and white cultures in the South became more homogeneous.

By the nineteenth century, African Americans had clearly established a penchant for corn, rice, greens, pork and pork-seasoned foods, and fried foods. Over time, the planter class took great delight in the dishes of their slaves, such as chitlins; turnip greens, collards, and kale simmered with smoked pork parts; roasted yams; gumbos; hopping John, corn bread, crackling bread, and cobblers; and various preparations of wild game and fish.19 Masters, claimed historian Eugene D. Genovese, “imbibed much of their slaves’ culture and sensibility while imparting to their slaves much of their own. . . . Slavery, especially in its plantation setting and in its paternalistic aspect, made white and black southerners one people while making them two.”20 Accounts of food eaten by white planters support this assertion. For instance, on the tobacco plantation in St. Petersburg, Virginia, that Olmsted visited, enslaved Africans covered the big-house table with platters of hot corn bread, sweet potatoes roasted in ashes, and fried eggs. More enslaved waiters arrived from the cookhouse bearing plates of cold roast pork and roast turkey, fried chicken, and an opossum cooked in such a way that, according to Olmsted, it “somewhat resembled baked suckling-pig.”21 Traditionally opossum was one of several victuals that slaves obtained on their own to supplement their woefully inadequate slave rations. Former Maryland slave Frederick Douglass described how, when given free time, the “industrious ones of our number would employ themselves in. . . hunting opossums, hares, and coons.”22 Here, however, it is served by slaves to whites. Similarly, yams before the nineteenth century were part of what planters distributed as slave rations. But by the mid nineteenth century planters in the South no longer considered sweet potatoes and yams the food of slaves. At the Virginia tobacco plantation, Olmsted recalled, “There was no other bread, and but one vegetable served—sweet potato, roasted in ashes, and this, I thought, was the best sweet potato, also, I ever had eaten.”23

The great complaint of the slaves was the monotony of their assigned diet of largely salt pork and cornmeal. In addition to raising chicken and pigs and hunting small game, they also responded by growing beans and greens. Through their own efforts they created heavily seasoned preparations of chitlins, collard greens, okra, and turnip greens and dishes such as hopping John. Genovese holds that enslaved Africans were not alone in enjoying these classic soul food dishes. Both poor whites and those in the planter class enjoyed them too. Blacks created the dishes, prepared them for their masters, and, in Genovese’s words, “contributed more to the diet of the poorer whites than the poorer whites ever had the chance to contribute to theirs.”24 Speaking of poor whites in rural South Carolina, Olmsted observed, “Their chief sustenance is a porridge of cow-peas, and the greatest luxury with which they are acquainted is a stew of bacon and peas, with red pepper, which they call ‘Hopping John.’” Poor whites, in Olmsted’s estimation, seldom had any meat, he said, “except they steal hogs which belong to the planters, or their negroes, and their chief diet is rice and milk.”25 Food scholars generally recognize rice as a staple as an African introduction to the Americas. In Brazil, Feijoada, the staple of most slaves, was made from black beans, jerked beef, and rice slaves received as rations. They enhanced the rations used to make feijoada by adding spices and discarded animal parts like tongues, ears, feet, and tails from slaughtered farm animals. They also added caruru (cooking greens) and large amounts of pepper.26

Afro-Cuban cooks viewed a huge dish of cooked rice as an essential accompaniment to any meal they served. Without rice, Cubans of all complexions and classes regarded meat and other dishes at the table with indifference.27 A similar attitude about the necessity of rice at every meal developed among black and whites in low-country South Carolina and Georgia.

Olmsted describes another example of Africans and Europeans sharing a culinary tradition among a steamship crew in Mobil, Alabama. “The crew of the boat. . . was composed partly of Irishmen, and partly of negroes; the latter were slaves, and were hired of their owners at $40 a month—the same wages paid to the Irishmen.”28 Olmsted observed, “so far as convenient” the ships captain kept the blacks “at work separate from the white hands; they were also messed separately.” As members of the same working class onboard the ship, the black and white crewmen ate the same food. “The food, which was given to them in tubs, from the kitchen, was various and abundant, consisting of bean porridge, bacon, corn bread, ship’s biscuit, potatoes, duff (pudding), and gravy.”29

In Louisiana, working-class blacks and white shared similar culinary histories as consumers of foods purchased on the streets of New Orleans. In the Crescent City, African Americans wearing bright handkerchiefs as head wraps carried baskets and basins containing fried chicken and fish dinners that they sold to dock workers. Moreover, New Orleans residents sold out of their homes food typical of African American cuisine. “Those fresh from the gombo [sic] soup, and the ham, and the punch and julep, rushing back again. . . . I tremble to think of. . . punches, and nogs, and soups, and plates of fish, and game, and beef and loaves of bread, that I have seen appear from side doors and vanish” for a dime each.30 A similar commercial and culinary culture developed in nineteenth-century Brazil. In Rio, African Brazilian street vendors gained fame for the sale of a fish meal called batatas doces, described as sardines fried in dendê oil and broiled shrimp served with spinach, hearts of palm, and sweet potatoes.31

By the eve of the Civil War, whites in the South of all classes had accepted black cookery and made it part of their everyday cuisine. Nineteenth-century accounts tell us that whites who lived and worked in close proximity to slaves typically ate the same cheap, delicious, and filling dishes that slaves developed to temper the monotony of their food rations.32 The same development occurred in Brazil, where black majorities shaped the cuisine of whites. By the mid-nineteenth century, feijoada was a staple of Brazilians of all classes. Travelers Louis and Elizabeth Agassiz noted that there was “no house so rich as to exclude” feijoada from the table. Depending on the region, the same could be said for corn bread, rice, and salt pork in the United States.33 In short, whites and blacks influenced each others’ foodways, if in different ways. Whites provided the material culture and adopted the culinary creativity of their African American cooks, coworkers, and neighbors. By the nineteenth century, the majority of the poor white population in the South enjoyed all parts of the hog, corn bread, greens, sweet potato pie, candied yams, and black eyed peas and rice. On the eve of the Civil War, poor white and black southerners were eating the same diet, based on greens, rice or corn, and skimpy amounts of meat.34

THE CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION

During the Civil War (1861–1865) both Confederate and Union soldiers very often depended on African American cooks on the battlefield. Northern army officers put free-born blacks and runaways into segregated regiments, paid them less than white soldiers, and fed them inferior food. Union officers subjected African Americans to corporal punishment evocative of their enslaved experience and assigned them menial duties like cooking rather than combat. In a March 1863 letter from Washington, D.C., for example, H.W. Halleck, apparently a high-ranking member of the Northern strategic command, suggested ways to organize black troops in the field along the Mississippi River. He writes, following the example of one General Banks near New Orleans, that freedmen “can be used to hold points on the Mississippi during the sickly [malaria] season” and they “certainly can be used with advantage as laborers, teamsters, cooks, &c.”35

FIGURE 3.1“Sweet Potatoe Planting—James Hopkinson’s Plantation, Edisto Island, S.C, April 8, 1862.” Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Southern armies also used the labor of slaves and free blacks for menial tasks like cooking. President Jefferson Davis ordered planters to turn over one out of every ten slaves for voluntary war labor. These “Negro servants,” as the Confederates called them, cleaned and cooked whatever soldiers caught, shot, and gathered as food.36

Pork and corn bread, sweet potatoes, and sweetmeats represented the most requested foods among Southern troops both black and white. In the Union army, African American troops requested additional corn bread and pork as rations. When commissary officials complied, southern-born white soldiers celebrated the change, while “their Northern-born comrades, accustomed to beef and wheat bread, complained bitterly.”37

For most of the war, the South had no trouble producing food for its soldiers, though by its end, in 1865, Northern forces had advanced deep into the black belt, and pitched battles and foraging soldiers had ruined productive fields and reduced domesticated hogs and wild game almost to extinction.38 Getting provisions to the field, however, represented the Confederate command’s greatest shortcoming. There was a shortage of salt and other preservatives to keep the food and a shortage of money and transportation to ship it. Confederate forces were constantly short of cans, boxes, and barrels for shipping food to the battlefields. With the lack of regular food shipments, soldiers survived on handouts from civilians, rations taken from the remains of dead Union soldiers, and sustenance found foraging in the woods and raiding civilian homes and farms. Soldiers fighting along the Atlantic Coast also fished.

When they did obtain food, soldiers then had to confront a shortage of cooking utensils.39 Some made them from the bottom halves of captured canteens and cooked meat on the points of sharp sticks. Others mixed meal and flour in turtle shells, calabashes, shirttails, and other makeshift containers. By the end of the war, many white soldiers who previously had no cooking experience became experts at creating what became southern delicacies after the war: huckleberry pie, roast pork, turkey, and opossum. For black southerners, preparing such dishes was nothing new.

FIGURE 3.2 African American army cook at work in City Point, Virginia. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-B811-2597.

EDUCATION, CLASS, AND THE AFRICAN AMERICAN DIET IN THE NEW SOUTH DURING RECONSTRUCTION

Various forms of tenant farming replaced plantation slavery. Sharecropping and tenant farming did very little to improve the nutritional conditions of the freedmen. Most southerners continued hearth-cooking practices and existed largely on simple diets reminiscent of the antebellum period. As one historian concluded, the “three M’s, that is, meat (meaning salt pork), meal, and molasses, continued as the core diet.”40 Samuel H. Lockett, who traveled through Louisiana in 1871, argued that the people of the South needed to reform their eating habits:

The greatest drawback to the people in the pine woods [referring to the South in general] is the manner in which they live, I mean the food they eat. Three times a day, for nearly 365 days of the year, their simple meal is coarse corn bread and fried bacon. At dinner there will be added perhaps “collards” or some other coarse vegetable. Even when they have fresh meat or venison, which they can obtain whenever they wish, it is always fried and comes to the table swimming in a sea of clear, melted lard. Chickens, eggs, milk and butter, all kinds of vegetables and fruit they could have, but have not. I really believe that the best missionary to send among them would be a disciple of A. Soyer, the great French cook. Let him preach “good health by good living,” distribute throughout the Piney Woods and, in fact, throughout the rural districts of much of our southern country, dime cookery-books, and sell all the frying pans, and the mental, moral, and physical condition of the population would soon be immensely improved.41

Yet, Many African American sharecroppers and tenant farmers almost starved to death because they moved too often to be able to develop the type of gardens they had used to supplement their diets during the antebellum period. As a result, they ate very unbalanced meals full of saturated fats. In addition, beginning in the late 1870s, they began purchasing highly processed food staples. For example, groups of poor southerners increasingly turned to merchants for cornmeal and white flour. New high-efficiency roller mills increased the production speed of these staples, but they also stripped the processed grains of their healthy nutrients and fiber.

In the late 1880s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture—in collaboration with two historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), Tuskegee Institute and Hampton Institute—performed dietary studies of African American farmers in the vicinities of Tuskegee in Macon County, Alabama, and Hampton in Franklin County, Virginia. These studies examined over a dozen families. Investigators visited each house for two weeks, “taking specimens for analysis, notes being made at the same time regarding the people, their dwellings, farm work [agricultural practices], habits, and the like.”42 These studies provide details about the eating traditions of southern farmers in the late nineteenth century.

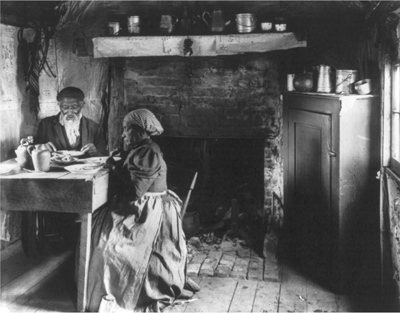

FIGURE 3.3 Old African American couple eating at a table by a fireplace in rural Virginia. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-61017.

For example, it appears that the majority of the farmers in the region of Tuskegee cultivated gardens where, during different seasons, they raised a variety of vegetables, including turnips, corn, collards, cabbage, and string beans. One recipe for “ol’ cabin cabbage” said that everybody knew how to make this cabbage dish that left an odor so strong “that when tomorrow comes you kin tell you done had cabbage yesterday.” The recipe described the odor as one of those “lingerin’ smells that hides aroun’ in the cornders an’ oozes up outer of the cracks long after the cabbage done et up an’ forgot about all ’ceptn them folks what can’t eat cabbages an eats it anyhow.” According to the recipe, the cook put on “the pot with a hunk er meat an’ a cabbage kivered with water an’ lets it bile an’ bile till you can’t tell the meat from the cabbage and cabbage from the meat.”43

Farmers prepared collards and turnip greens more than any other vegetable because they had a much longer growing season and could be obtained at almost any time of the year. Good collard greens, according to one cookbook, called for a ham hock, but the cook added that a “hunk of fat back’ll do.”44 To make southern-style collards, “Keep yo’ meat an’ green stuff well kivered with bilin water an’ let it all cook some two hours. Don’t bile fast but jes’ let yo’ pot simper along slowsome. A piece of red pepper pod ain’t gonter hurt the seasonin’ none, an’ use your gumption when the bilin’ air pretty nigh finished ’bout whether or not mo’ salt air a needcessity.”45

African-American cooks did not restrict the use of fatback to cooking cabbage and collards. One study of eating habits among African Americans in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia showed that parents gave crying babies a piece of fatback as a pacifier. Parents also introduced fatty bacon, commonly called a “streak of fat and a streak of lean” and other forms of pork into their children’s diets at an early age.46 Southerners used cured pork as a flavor booster, not as the center of the meal. As Joyce White remembers from her childhood in Choctaw County, Alabama, “Turnip, mustard, and collard greens glistened with a few slivers of ham hocks, and so did crowder peas and butter beans. A meaty ham bone was simmered with potatoes and green beans or with tomatoes, rice, corn, and okra for delicious stews.”47 Like corn bread, sweet potatoes, and yams, pork became part of the southern African American’s diet during infancy. This made it very difficult for many African Americans in their adult years to imagine a life without it.

Very few African American farmers in Macon County, Alabama, owned land in 1895 and 1896. Instead, most farmed on property owned by white landlords. Their livelihood depended on how many bales of cotton they could grow, and therefore they devoted little time to raising subsistence crops. Generally, they dedicated their fields to cotton, with some corn, sweet potatoes, and a few other food crops. Most of the residents in the region around Tuskegee Institute, both black and white, ate a diet of “fat salt pork, corn meal, and molasses.” Farmers produced some molasses and cornmeal and bought some from stores. Participants in both studies received a large amount of their nutrition from “unbolted [unsifted] corn meal,” which, in the late 1890s, cost about a cent a pound.48 Unbolted cornmeal, though processed, retained a large amount of bran, which plays a vital role in maintaining a healthy colon.

Farmers also raised and killed their own hogs. In most cases, however, the fat salt pork purchased in large quantities at southern markets came from meat-packing houses in Chicago and elsewhere. In Macon County, when a person referred to meat, he or she “always meant fat pork.” The authors of the Tuskegee study wrote, “Some of them knew it [meat] by no other name, nor did they seem to know much of any other meat except that of opossum and rabbits, which they occasionally hunted, and of chickens, which they raised to a limited extent.” One cook wrote that fried chicken was “hard ter larn a new cook ter do.” The cook added that it is easier to fry greasy than not and the “cook what dishes up greasy fried chicken oughter go out an’ wuck in the fiel’ whar she b’longs.”49

FIGURE 3.4 Ten African American women in a cooking class at Hampton Institute, Hampton, Virginia. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-95109.

In Franklin County, Virginia, African American sharecroppers ate very little or no beef, mutton, or other leaner meats, because they believed that those meats would make them sick. In addition to fat pork and wild game was part of their definition of meat. Generally, cooks boiled game in water until the meat fell off the bone, then seasoned and baked or barbecued it. In Alabama, no barbecue was considered done unless the meat was “saturated with blistering sauces.” For example, cooks in Eufaula, Alabama, basted the cooking meat, “whether it be pork, beef, lamb, kid, or chicken,” with a “mixture of vinegar, mustard, catsup, Worchester sauce, olive oil, Tabasco sauce, lemon juice and whole red peppers in great quantity. The sauce is boiled for three minutes after mixture before being applied to the meat.” The barbecuing and basting would last for hours, until the meat was an “aromatic brown.” 50

In addition to barbecued meat, those in close proximity to water consumed sizable of quantities of fresh, salted, smoked, and fried fish. In Franklin County, in the Chesapeake Bay region, families ate eel, herring, mullet, roach, blue croakers, trout, and perch. Except in Florida and Georgia, southerners considered turtle a favorite dish, typically cooking it in a pot as part of a soup or stew. Eel and frog were considered delicacies as well. Southerners seasoned and batter-fried them just like catfish. Fish and small game remained popular because one could cook and eat them in one or two meals, which reduced the chances that the meat would spoil and harm someone.51

FRIED FRESH TROUT

Slice salt pork thin and fry until crisp. Remove and set aside. Dredge trout in flour or roll in cracker meal. Sprinkle with black pepper. Fry in the hot salt pork fat until deep brown. Serve garnished with parsley and fried salt pork.

Pearl Bowser and Joan Eckstein, A Pinch of Soul in Book Form (New York: Avon, 1969), 225.

During lean times, some trapped and sold rabbits as a way of earning extra money. The poor consumed small game such as rabbits because they did not have the technological ability to preserve and/or refrigerate much of anything. In many parts of the South, people stored their perishables in small portable wooden cupboards or dairies with no refrigeration capacity. In addition, the poor grazing lands in the South raised comparatively few beef cattle and sheep. The meat that was procured was inferior to that raised in the Southwest and Midwest. One scientist involved in the study of black farmers in the South concluded: “The scarcity of fresh meat and the difficulty of preserving it doubtless goes far toward explaining the [preference for salt pork] in the dietary tastes and habits of the people in general in this region, if not elsewhere in the south.”52

WILD HARE IN TOMATO SAUCE

1 cup meat from a young rabbit

flour for dredging

salt and black pepper to taste

bacon fat

4 scallions with tops, sliced

2 cloves garlic, crushed

sprig of fresh parsley

4 tbs. butter

2 tbs. Worcestershire sauce

2 cups tomato juice

½ cup milk

1 tsp. minced sweet basil

Roll rabbit pieces in flour seasoned with salt and pepper. Brown in bacon fat. Make a sauce with sliced scallions, crushed garlic, parsley, butter, salt, Worcestershire sauce, tomato juice, milk, and basil. Pour over the rabbit while it is still hot. Cook 2 hours in a covered pan, then remove lid and cook 15 to 20 minutes more, reducing the sauce. Thicken sauce with a little cornmeal mixed with water if it is thin.

Pearl Bowser and Joan Eckstein, A Pinch of Soul in Book Form (New York: Avon, 1969), 215.

Technological stagnation also explains the continuation of simple and primitive cooking methods in late-nineteenth-century southern cooking. Most southerners, black or white, could not afford a stove. Instead, they continued to cook in the ashes of a fireplace or with iron pots and pans over the hot embers of a fire. For example, in Macon County, Alabama, only two of the families in the study had enough money to own a stove, and, in Franklin County, Virginia, several women interviewed said they did not bake bread because they did not have an oven. Other women interviewed complained that store-bought, highly processed loaves of white bread lacked any kind of savory, mouthwatering appeal. Instead, they preferred various types of corn and wheat flour biscuits. Southerners made and ate biscuits sliced in half and stuffed with pork, fried eggs, cold baked sweet potatoes, and other items. Pone bread, johnnycakes, hoecakes, and ashcakes from the colonial period remained very popular because most southerners owned very few cooking utensils. Some recognized that consuming small amounts of ash and charcoal cured flatulence and upset stomachs. As a result, they sometimes ate pone bread baked in ashes without cleaning it off.53

In the 1890s, black farmers in and around Tuskegee, Alabama, were still preparing cornmeal in ways that dated back to the antebellum period. “The daily fare,” wrote John Wesslay Hoffman, agricultural chemistry and biology teacher at Tuskegee Institute from 1894 to 1896, “is prepared in very simple ways. Corn meal is mixed with water and baked on the flat surface of a hoe or griddle. The salt pork is sliced thin and fried until very brown and much of the grease is fried out.” He went on to say, “Molasses from cane or sorghum is added to the fat, making what is known as ‘sop,’ which is eaten with the corn bread.”54 In general, among southerners, corn bread was the staff of life, and preparing the easy-to-make batter became a daily routine. Southerners usually ate corn bread Monday through Friday and biscuits on the weekend and on special occasions. In addition to ashcakes and hoecakes, southerners also made crackling bread, or fatty bread, out of cornmeal.

Farmers in Charleston County, South Carolina, made crackling bread in the wintertime during hog-killing days. The fat of the hog was cut into cubes and rendered in a wash pot set over a hot fire. The skin, writes Wendell Brooks, rises “to the top of the boiling grease, growing shriveled and brown.” A cook would skim off these cracklings and then press them to remove excess grease. To make delicious golden brown crackling bread, an African-American recipe from North Georgia called for two cups of cornmeal with one cup of crackling. Add “salt, soda, buttermilk and enough water to make a soft dough (or use ⅔ cups of buttermilk). Bake pretty brown.” Definitions and recipes for crackling bread varied across the South. For example, black farmers in Tuskegee, Alabama, made theirs with crisp pieces of fried bacon, cornmeal, water, soda, and salt and, according to Hoffman, “baked [it] in an oven or over the fireplace.” Characteristically, cooks boiled or fried their food, and most dishes arrived at the table stewed or very crisp. According to Hoffman, many black farmers in the study suffered from various forms of indigestion because they consumed large amounts of fried foods.55

Fried pork and cornmeal in one shape or another appeared daily in the southern diet. A list of foods eaten by more affluent African American families in the study showed more variety, however, including dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and better cuts of meat. Those who ate greater amounts of fruits and vegetables tended to live near the influence of the Tuskegee and Hampton institutes. According to the food studies’ government researchers, these families did not represent the average black belt residents. Apparently, increased educational opportunities and earning power improved the eating habits of southern farmers. In short, Tuskegee and Hampton improved the diets of the farmers within their sphere of influence. In addition, in contrast to those in Macon County, Alabama, African Americans in Franklin County, Virginia, had greater access to fish and therefore healthier, leaner forms of protein.56

Historians still know very little about how diets changed after the Civil War and the role diet played in elite white- and black-led reform efforts at the turn of the century. There is a body of literature on food reform within the history of the vegetarian movement led by elite white reformers during this period. That movement, however, occurred principally in the Northwest and Northeast and made very few inroads among southerners, black or white.57 Regarding white Southern elites, Historian Joe Gray Taylor insists that after the Civil War they did not shun black eyed peas, grits, or collard greens as white elites in the North did. He writes, “with the exception of New Orleans and possibly Charleston and Baltimore, the concept of fine food in the European sense hardly existed in the Old South.” Instead, southern elites inherited from “British yeoman, from the Indian, and from the frontier. . . a preference for large amounts of different kinds of good food rather than a few dishes of presumably superb food.” Taylor goes on to say, “the most striking fact about the diet of the New South, from the Civil War through World War II, is not that it changed, but how little it changed.”58

The literature on the Tuskegee Woman’s Club, started in 1895, and similar clubs at the Hampton Institute sheds very little light on upper-class black women’s efforts to reform the African American diet in the South.59 Most of these black self-help organizations were controlled by upper-class women. For example, the Tuskegee Women’s Club only admitted female faculty members of Tuskegee or wives or female relatives of male Tuskegee faculty. Most of these women’s clubs left a more substantial paper trail about their struggles to stop the tide of lynching that racked the country at the turn of the century than on their efforts to reduce the amount of fried foods African Americans were eating.60

African American Margaret Washington, the wife of Booker T. Washington and founder of the Tuskegee Woman’s Club, was a typical progressive era reformer in many ways but not in all. She championed Tuskegee’s mantra of “Bath, Broom, and Bible,” that is, cleanliness and Christian morality.61 She put great emphasis on developing biblical motherhood and wifehood in the rural women of Tuskegee, Alabama. What was different about her and other black reformers of the turn of the century, however, was a conservative black nationalism. The first lady of Tuskegee put particular emphasis on teaching black history and encouraging black landownership, which she believed would lead to black economic independence. Margaret Washington’s focus on African American property ownership, which she called an obtainable goal, was a sharp contrast to other women’s club leaders of the period who spent their energy fighting for women’s suffrage. Yet there is evidence that crusaders at the Tuskegee and Hampton institutes encouraged African American farmers to produce most of what they cooked, consume less fried food and fatback, and diversify their diets. And, while they did not reduce fat and fried food consumption that much, black farmers close to Tuskegee and Hampton did grow more of what they ate, to the benefit of their diet. These farmers ate foods free of harmful pesticides. They also ate large amounts of fiber-rich cornmeal, while the lye that went into processing their hominy cleansed both the liver and stomach.

The Tuskegee Woman’s Club did provide cooking classes through the college, but scholars provide no details about the instructional content of the classes.62 Some insights, however, can be gleaned from Booker T. Washington himself. In a letter dated November 23, 1899, to one of his school administrators, Washington writes: “I call your attention to the enclosed bill of fare for the students. It seems to me that they are having too much fat meat; you will notice that they had bacon and gravy for two meals.”63 Like Professor Samuel H. Lockett before him, Washington wanted blacks to consume less salt pork and fat. Perhaps reducing the amount of fried foods was a goal of his wife’s reform agenda and cooking classes?

Another insight into black reform movements and the southern diet comes from a look at the institute’s menu. It shows that students at Tuskegee ate far more broiled foods than did African American farmers in Alabama, who seemed to have fried food with almost every meal. The Wizard of Tuskegee, as Booker T. Washington was called, was a micromanager in advancing his agenda. For example, he assigned African American Laura Evangeline Mabry the job of campus food critic, or dietitian. From Birmingham, Alabama Mabry graduated from Tuskegee in 1895 and stayed on as member of the school’s staff until 1901. In a report to Washington on the institute’s cafeteria dinner menu, she comments on the fare: “Boiled Peas. Boiled Sweet-potatoes. Stewed beef and Corn bread. The peas were boiled without fat. Enough hard corn was found in the peas to make them unpalatable and unattractive. The beef was not seasoned with pepper and salt, but the onions added much to the taste. Potatoes and bread were nice and hot.”64 Perhaps this menu reflects how Margaret and Booker T. Washington wanted all black folks to cook their food—though presumably with properly cooked corn.

Atlanta University graduate James Weldon Johnson also complained about the extent of fried food and fatback consumption among rural blacks in Georgia. Johnson, an African American from the city of Jacksonville, Florida, did a stint as a rural teacher during which he boarded with a family in Hampton, Georgia, thirty miles south of Atlanta. For the first two or three weeks, his landlady served him “fried chicken twice a day, for breakfast and supper.” Thereafter the menu “steadily degenerated until my diet was chiefly fat pork and greens and an unpalatable variety of corn bread. For a while I lived almost exclusively on buttermilk, because I could no longer stomach this coarse fare.” He adds, “Then it was that I looked longingly at every chicken I passed, and would have given a week’s wages for a beefsteak.”65 Again, we see an upper-class southerner complaining that the lower classes fried too much of their food and did not include enough variety in their diet.

In general, black southerners after the abolition of slavery continued to exist on a diet of salt pork and corn bread. Emancipation did give them greater access to poultry, however, resulting for some in the cooking and consumption of fried chicken “for breakfast and supper.” Fruit cobblers, biscuits, turnips, sweet potatoes, and polk salad (also called poke sallet, greens from the pokeberry or poke plant) were also familiar foods in black southern homes. Some southern families ate polk salad boiled or floured and deep-fried like okra. Others served peas, beans, cabbage, and greens. Studies of late-nineteenth-century eating habits conclude that the poorest families suffered not from an insufficient quantity of food but rather from a lack of quality and variety. A special concern was the ability to obtain fresh fruits and vegetables during the winter and early spring, when most working-class families ate a monotonous nitty-gritty diet heavy on potatoes, cabbage, and turnips. High milk prices also put that source of vitamins and minerals out of range for most poor black families. One traveler observed that those without milk to make butter would instead use “bacon grease on the biscuits and corn bread, or you could dip it in the stewed tomatoes.” Thus, those with a cow or goat had better and more diverse diets.66

Middle- and upper-class African Americans did share some eating traditions with poorer southern African Americans. For example, cooking chicken, some form of corn, and one-pot meals was common to African Americans of every status. In the 1880s, the family of middle-class African American James Weldon Johnson preferred eating “soul-satisfying” dishes such as gumbo, fried chicken, and hominy. Sausage and hominy or hog and hominy was a popular breakfast. Gumbo and rice was an equally popular soul-satisfying dish. Johnson recalled the unforgettable experience of eating some gumbo made by a Charleston, South Carolina, migrant named Mrs. Gibbs. She made her Charlestonian gumbo in a large pot similar to those used in the old slave quarters. In it she put okra, water, salt and pepper, “bits of chicken, ham first fried then cut into small squares; whole shrimps; crab meat, some of it left in pieces of the shell; onions and tomatoes; thyme and other savory herbs.” Then she slow cooked it for hours and served the gumbo over white rice.67

Johnson grew up living with his father, who was from Richmond, Virginia, and his mother and maternal grandmother, both natives of the Bahamas. “My grandmother was especially skillful in the preparation of West Indian dishes: piquant fish dishes, chicken pilau, shrimp pilau, crab stew, crab and okra gumbo, hoppin’ John, and Johnny cake.” Soups and stews remained important staples in many parts of the South because of their ability to feed several mouths with a small amount of meat or fish. While Johnson describes his grandmother’s cooking as West Indian, descendants of slaves in the United States, Cuba, and Brazil prepared similar dishes with African ingredients like okra.68

In addition to rice, poor folk throughout history have also had an enduring relationship with fried fish. When fat or oil is heated to the high temperatures necessary for frying, its chemical composition changes, and the body’s enzymes have trouble breaking it down. As a result, the body must work harder and longer to gain any benefit from a dish such as fried fish. As we now know, Africans along the Senegal, Gambia, Niger, and Congo rivers received a sizable percentage of their protein in the form of smoked, salted, and fried fish. This tradition continued in South Carolina and Virginia into the twentieth century. African Americans living near bodies of water ate lots of fish, both fresh and canned. After the turn of the century, canned salmon was so cheap that southerners purchased it to make salmon cakes or to eat plain. Similarly, they purchased canned oysters and sardines and ate them with crackers. Yet fried catfish and porgies remained the most popular fish preparation by far. “Southerners believed that God made fish to be fried,” writes one historian of the South.69

After the Civil War, the consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables decreased as owners of large plantations were no longer required to grow them for slave rations. The orchard, across the South, insists one historian, “almost disappeared from the commercial plantation and was confined to the land of the provident yeoman farmer. As the twentieth century wore on, those who grew fruit found fighting insects and fungus a difficult and expensive proposition.”70 Commercially producing fruit orchards may have disappeared, but many African American families in the South continued to cultivate gardens that supplied their tables with fresh peaches, berries, and grapes. For farmers who dedicated land to subsistence farming, like those around the Tuskegee and Hampton institutes, there were thus healthy aspects to the southern African American diet. As I shall discuss, the tradition of subsistence gardening went with African American southerners when they migrated north to states like New York.

SPECIAL OCCASIONS: LATE-NINETEENTH-CENTURY REVIVALS

After settling the question with his bacon and cabbage, the next dearest thing to a colored man, in the South, is his religion. I call it a “thing,” because they always speak of getting religion as if they were going to market for it.

—WILLIAM WELLS BROWN—

“Black Religion in the Post-Reconstruction South” (1880)

Religious traditions and eating on special occasions became even more established in African American communities after emancipation. There are many different churches within most African American communities, but the food celebrations remain consistent.71 These events increased the association between soul and food in black communities: religion nourished the soul while food nourished the body. African Americans at the turn of the twentieth century were largely an agricultural group made up of hardworking farmers and farmhands. Working off a heavy Sunday breakfast or dinner on the grounds during a revival or on Christmas or New Year’s Day was much easier for them than for their descendants in the industrial society of the late twentieth century.72

In 1895 and 1896 African American farmers in the vicinity of Tuskegee, Alabama, generally worked “about seven and a half months during the year,” according to researchers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “The rest of the time,” says one researcher, “is devoted to visiting, social life, revivals, [and] other religious exercises.” During the “laying-by time,” while the crops were maturing, African American farmers near Tuskegee held “bush meetings” and revivals and visited friends for sometimes a whole week at a time.73 Writing in 1903, W. E. B. Dubois insisted that, at the turn of the century, the church represented “the social centre” of African-American life: “This building is the central club-house of a community of a thousand or more Negroes. Various organizations meet here—the church proper, the Sunday-school, two or three insurance societies, women’s societies, secret societies, and mass meetings of various kinds. Entertainments, suppers, and lectures are held besides the five or six regular weekly religious services.”74

Revivals and the centrality of the church in the lives of African Americans continued into the 1920s and 1930s. These were two important decades in American history, during which southern-born African Americans migrated to the North in large numbers. Most migrated in search of better-paying jobs and housing. Others fled to escape oppressive race relations and the jim crow policies that began after the end of Reconstruction.

THE NADIR BEFORE THE GREAT MIGRATION

Historians have called the period before the Great Migration (discussed in the next chapter) the nadir of race relations in the United States. In the late nineteenth century, conditions for black southerners became deplorable as northern politicians began dismantling Reconstruction in 1877, abandoning black southerners. Southern racists in the United States produced an abundance of anti-African-American literature, and bigots among predominately southern white Protestant church leadership declared the virtues of black subordination to whites in all facets of life. For black southerners, it became increasingly more difficulty to exercise their rights as U.S. citizens after northern politicians removed federal troops from the South.75 For example, during his visit to the lower Mississippi region in the 1880s, Austrian writer and traveler Ernest Von Hesse-Wartegg asked, “What are these causes that have set Negroes on the move? Poverty and distress in the South since the war and bad treatment from planters and officials.”76

In 1881 the Weekly Louisianian carried a story on why a group of African Americans had left North Carolina for Indiana. The black North Carolina natives explained that “although nominally free since the war, our condition in the South was in fact one of servitude, and was each year becoming worse.” Economically, their wages were “only sufficient to sustain our lives with the coarsest food, cover our bodies with the poorest raiment, and shelter us in the [most] wretched habitations,” they wrote. Politically and socially, “when the laws were not made to discriminate against us outright, they were so administered as to have the same effect.” Local magistrates in North Carolina used every pretext to “send men of our race to the penitentiary, while white men were unmolested who committed the same offenses. . . . More and more each year we were deprived of our political rights, by fraud if not by violence. There was no security for our lives.”77

Security for African Americans grew worse with the election of President Woodrow Wilson (1913–1921). Wilson demonstrated that he was either unaware or uninterested in conditions facing black southerners by staging the premier for the racist pro–Klu Klux Klan film The Birth of a Nation in the White House. Furthermore, he remained inactive during a number of race riots that happened during his administration, in East St. Louis, Charleston, Houston, Knoxville, Elaine (Arkansas), and Tulsa, in which hundreds of blacks were murdered. Over time African Americans learned that Wilson’s silence in the midst of racist atrocities committed by whites was a deadly combination. It became clear that he was no champion of democracy and justice for all U.S. citizens. Taking their cues from the Wilson administration, officials at the local level around the nation remained apathetic to the complaints of the friends and families of African American victims of lynchings, arson, and beatings committed by both civilians and police officers between 1913 to 1922.78

Black folk were determined to defend their citizenship rights against white racist aggression. The assertiveness of African American veterans of the world war clashed with the determination of racist whites to reestablish the pre-WWI subordination of African Americans. In communities where riots erupted, supporters of the jim crow power structure encountered little restraint from local officials when they mobilized to crush outspoken and armed African Americans. Research on racial conflict across the country during the nadir indicates that southern whites were trying to regain self-confidence by practicing violent white supremacy rituals: beating, raping, shooting, lynching, and torching African Americans and destroying their important social and economic infrastructures.79

In the aftermath of several riots, one black southerner in 1921 concluded that African Americans, “especially the Southern wing of the race is tired of un-Godly principles being meted to us.” He called jim crow an “un-American, unprincipled, and inhuman” system.” He added, “No Colored man is safe here, no matter what his social, political, or financial status in the community. We are looked upon as outcasts, vagabonds, or anything other than an American citizen.”80