The Origins and Meanings of Soul and Soul Food

Born and raised in Augusta, Georgia, singer, songwriter, and choreographer James Brown is considered the undisputed father of soul. In his autobiography, he writes that by 1962 soul “meant a lot of things—in music and out. It was about the roots of black music, and it was kind of a pride thing, too, being proud of yourself and your people.” He adds, “Soul music and the civil rights movement went hand in hand, sort of grew up together.”1 Before the civil rights movement, black entertainers like Brown, B. B. King, Ray Charles, Al Green, Gladys Knight, Nina Simone, and Aretha Franklin made their living on the “chitlin circuit,” a string of black-owned honky-tonks, nightclubs, and theaters. The circuit wove throughout the Southeast and Midwest, stretching from Nashville to Chicago and into New York. Performers would often do consecutive one-night stands, frequently more than eight hundred miles apart. The routine went: drive for hours, stop, set up the bandstand, play for five hours, break down the bandstand, and drive for several more hours. On the road, performers often settled for sandwiches from the colored window of segregated restaurants until they arrived at the next venue.2

On the circuit were the New Era in Nashville; Evan’s Bar and Grill in Forestville, Maryland (just outside of the District of Columbia); the Royal in Baltimore; Pittsburgh’s Westray Plaza, the Hurricane, and Crawford Grill; and New York’s Club Harlem and Small’s Paradise, to name just a few venues. The chitlin circuit was crucial to black artists like James Brown and B. B. King because it offered the only way for them to perform for their fans during a period when the white media did not cover and mainstream venues did not book black artists. The entertainers called it the chitlin circuit because club owners sold chitlins and other soul food dishes out of their kitchens. Early in her career, Gladys Knight performed in a house band on the circuit, playing at “roadside joints and honky-tonks across the South,” she recalled. “No menus. No kitchens. Just a grizzly old guy selling catfish nuggets, corn fritters, or pig ear sandwiches in a corner.”3 The circuit went beyond small hole-in-the-wall clubs, however. Elaborate African American–operated theaters like the Regent in Washington, D.C., the Uptown in Philadelphia, the Apollo in New York, the Fox in Detroit, and the Regal in Chicago were big-time venues considered part of the circuit.4 These theaters did not have kitchens that sold food, but savvy African American entrepreneurs established places nearby where you could purchase good-tasting meals.

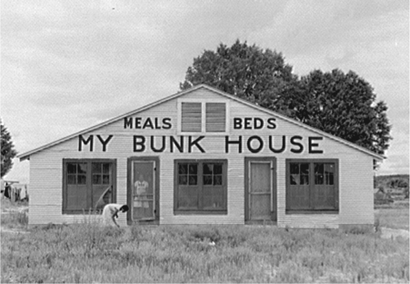

FIGURE 7.1 Negro bunkhouse, Childersburg, Ala., May 1942. Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF34-082813-C.

Various soul food traditions cropped up in connection with the circuit. In New York, for example, soul food was eating fried chicken and waffles—perhaps early on a Sunday morning after spending all night listening to bebop jazz musicians such as Miles Davis and Thelonius Monk. The legend goes that this northern soul food tradition began when artists in New York ordered chicken for breakfast after missing dinner on Saturday night because they were performing and ordered waffles as the hot bread to eat with the fried chicken. Similarly, at Kelly’s restaurant in Atlantic City, the queen of soul, Aretha Franklin, remembered after-hours meals of “hot sauced wings and grits for days.” Franklin also recalled that near Chicago’s Regal Theater there was a “food stand, tucked a few doors away from the theater, that served greasy burgers made with a spicy sausage in the meat, topped with crispy fries, Lord, have mercy. The artists couldn’t wait to get offstage to wolf down those burgers.”5 When performing in northwest Washington, D.C., African American entertainers ate at Cecilia’s Restaurant, conveniently located across the street from the Howard Theater. Harlem, the site of New York’s Odeon and the Apollo theaters, had a bunch of restaurants: Grits ’n’ Eggs, Well’s Waffle House, the Bon Goo Barbecue, the Red Rooster, and Tillie’s Chicken Shack, among others. Most of these restaurants had been open since the 1930s and 1940s. But nobody called them soul food restaurants then.

FIGURE 7.2 Negro café, Washington, D.C., July-November 1937. Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF34-008544-D.

It was in the 1960s that African American urban dwellers, first in the Southeast and then in the Northeast, gradually made the transition from talking about rock music (rhythm and blues) and southern food to calling it soul music and soul food. In the face of the increasing ethnic diversity of urban centers, soul became associated with African American culture and ethnicity. People with soul had a down-home style that migrants from the rural South could unite around. For this working class, composed predominantly of underemployed urban dwellers, soul made them members of an exclusive group of cultural critics. Soul gave them insider status in a racist society that treated them like outsiders, and it emerged as an alternative culture that undermined white definitions of acceptability.6

Beginning with discussions in the 1960s and 1970s, soul was considered the cultural component of black power, the most visible black nationalist idea of the twentieth century. At its heart, soul is the ability to survive and keep on keeping on despite racist obstacles to obtaining life’s necessities. In the language of soul, the more you have been through and survived, the more soul you have. Soul roots go back to the 1920s and the Harlem Renaissance movement.

THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF SOUL

The 1920s movement began after democratic struggles in Europe during the post–World War I era failed to carry over and improve conditions for blacks in the United States. Similarly, the black power and soul movements of the post–World War II era were, among other things, a response to the limited gains made after the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown vs. the Board of Education, the outlawing of school segregation, and the civil rights movement that followed. Black power and soul in their various manifestations, depending on the group, were rooted in the black revivalism of Malcolm X, the direct action protests as well as the political and economic organizing campaigns of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the armed resistance to police brutality of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. In addition, militant African independence movements in the 1950s and 1960s stirred African Americans to action, producing a new and “brilliant generation” of angry black intellectuals that rivaled those of the Harlem Renaissance.7

Both the urban riots that followed the assassinations of Medger Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and several other important figures within the civil rights movement in the 1960s and the failure of American liberalism shaped the development of soul. In Report from Black America, published in 1969, activist and civil rights strategist Bayard Rustin observed that African Americans in the early 1960s “began to get Blackenized.” Black power and soul proponents such as Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), H. Rap Brown, Amiri Baraka, and others called for “thinking black” and moving beyond the double consciousness outlined in W. E. B. Du Bois’s classic book The Souls of Black Folk to a new, independent, proud black identity. Rustin argues that soul was the cultural arm of the black power movement that called for, among other actions, singing, talking, and eating according to the African heritage of black people in America.8

In a 1967 article entitled “African Negritude—Black American Soul,” published in the journal Africa Today, W. A. Jeanpierre argues that soul is the same as African negritude. Both negritude and soul were political and cultural concepts rooted in the values that informed black Americans about African civilizations, black genius, and the things that made black people across the globe unique. The difference between negritude and soul was in their origins: elite African intellectuals, many of them living in Europe, created the idea of negritude; northern working-class urban African Americans with southern roots created soul ideology, which subsequently spread to more affluent northern black communities. From Jeanpierre’s article, one can conclude that there is a class and regional formula to soul: poor black folks have more soul than wealthier ones; urban black folks have more soul than suburban black folks. In this formula, the more black, poor, and urban you are, the more soul you have.9

Soul and soul food, according to one scholar, developed out of a larger black power project that called for creating black cultural expressions different from white society.10 Oral interviews conducted with those who lived through the civil rights and black power movements illustrate this point. For example, Lamenta Crouch, a longtime educator in Prince George’s County, Maryland, associates the term “soul food” with the black power movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Crouch graduated from an HBCU in Virginia in the 1960s and moved to Washington, D.C. She remembers black power in the metropolitan Washington area largely as a black identity movement. Crouch says, “I can’t remember exactly the first time that I heard it, but it was in the same era of black power, soul brother, and all that business of having an identity that was uniquely ours.” She adds, “It was during that era that the soul food term came up and I think it was kind of like, ok this is ours. This is something we can claim is ours that identifies us as a people and we [have] some value and we have something to contribute.”11

Clara Pittman observed that black power in northern California inspired black people finally to stand up for their rights and “speak for themselves,” openly expressing a pride in their unique African heritage and an awareness of the contributions they made to American society. During the 1960s and 1970s, she was in her early twenties, just out of the Marine Corps, and living in northern California (not far from Oakland where Bobby Seal and Huey P. Newton started the Black Panther Party in 1966).12

In Westchester County, New York, black power did not have the kind of popularity or influence it had in the District of Columbia and northern California. Westchester residents born before the Depression had little to no experience with black power. For example, Ella Barnett, born in 1915, claimed “black power didn’t mean anything to me. It really didn’t make a difference.”13 Margaret Opie and Sundiata Sadique, however, both Westchester activists born in the 1930s, had a very different interpretation of the influence of black power in the county. Starting in the 1960s, Opie became very involved in local, county, and national politics. She held positions such as membership chair of the Ossining NAACP and director of the Center for Peace in Justice, which was started in Ossining and is now a countywide organization located in the county seat in the city of White Plains. She also held the position of director of the Ossining Economic Opportunity Center (one of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty programs) and was a 1972 delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Miami representing Westchester County.14

Sundiata Sadique, formerly Walter Brooks, moved to Westchester County in 1963 from just across the Hudson River in nearby Rockland County. After high school, he joined the U.S. Army, where he was a paratrooper in the 101st Airborne. After his tour was up, Sadique spent a brief period in Chicago, where the message of the Nation of Islam’s Elijah Muhammad and the Fruit of Islam (all the adult male members of the Nation who were trained in self-defense) attracted his attention. Before returning to Rockland County, he became a member of both the Nation and the Fruit of Islam. In Rockland, he served first as secretary of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and later became the chairman of the CORE chapter there. He came to Ossining in 1967 with Bill Scott, the chairman of Rockland County’s CORE chapter. When Sadique first arrived in Ossining, he took a job cutting hair at George Watson’s barbershop. From the town’s only black barbershop he started recruiting and organizing blacks for both the Nation and CORE, selling copies of the newspaper Malcolm X started while he was a member of the Nation, Muhammad Speaks. (The photographer for the Nation of Islam, Bernard Jenkins, also lived in Ossining.)15

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Nation, CORE, and the Black Panthers all launched organizing efforts in Westchester County. The Nation, an exclusively alternative black nationalist religious organization, had better results than the overtly political organizing efforts of CORE and the Black Panthers. Sadique and other members of the Nation living in Westchester County made the thirty-minute car or train trip to Harlem to attend Malcolm X’s Temple No. 7. Elijah Muhammad assigned Malcolm to New York to recruit the large number of blacks that lived in Harlem and the greater New York area.16

In his early days, Malcolm and his lieutenants carried out their proselytizing efforts in front of the Theresa Hotel located next to the Chock Full o’ Nuts Café at Seventh Avenue and 125th Street. Malcolm, a tall, handsome redhead, delivered his charismatic Black Nationalist critique of the problems of black society and the solutions offered by Elijah Muhammad standing on top of a wooden soapbox. In addition to his street-corner oratory, Malcolm and his followers at Temple No. 7 operated several restaurants in Harlem and a black nationalist newspaper with a distribution network that extended as far as the city of Peekskill in northern Westchester County. As Malcolm’s popularity increased, African Americans in and around Harlem flocked to hear him preach. Malcolm remained the minister in charge in Harlem until he left the Nation in 1964. Recruiting efforts continued to go very well after Malcolm’s departure, however, as evidenced by the establishment of a Nation of Islam temple and restaurant in the lower Westchester County city of Mount Vernon.17

In contrast to the Nation, CORE first came to northern Westchester to address problems within the local fire departments. In Peekskill, racist members of the city’s full-time professional fire department denied African American firemen the right to ride on city fire trucks, forcing the men to take taxis to fires. Similarly, racist members of the Ossining Volunteer Fire Department practiced a policy of blackballing that shut out African American volunteers. Despite its valiant efforts, CORE was unable to establish a local chapter in Ossining. The Black Panthers had similar organizing difficulties in northern Westchester.18

In the 1970s the Black Panthers established chapters in Chicago and New York City. They also attempted to make inroads into Westchester County with breakfast programs in poor black neighborhoods. In Ossining, however, where Sing Sing Prison was located, most African Americans viewed outsiders like CORE and the Black Panther organizers with contempt, fear, and suspicion.19

The older generation of African Americans, most of them southern migrants like Ella Barnett, were politically very conservative and disagreed with black power and black nationalism. Younger black folk feared law enforcement officials. Sundiata Sadique recalls that when he moved to Ossining, fear of the police paralyzed many black residents. Young activists like Margaret Opie, who became politically mobilized as members of the NAACP in Westchester, simply did not trust outside political operatives representing CORE and the Panthers. Maybe they suspected that they might really be undercover agents.20

Back in the 1940s, Westchester County had become an unfriendly place for black activists and the message of black power. The county had become like a police state, perhaps in response to the Peekskill Riots of 1949 and the communist hysteria surrounding the Rosenbergs’ execution at Sing Sing Prison in1953. “This was like a prison town and a police state to me when I started living here,” says Sundiata Sadique. “Black people were very afraid of law enforcement. So I think it had something to do with the prison, you know if you go back to the Rosenbergs when they saw that, when they were electrocuted in Sing Sing and the kind of turnout of the racist. . . so it took a while” to get black folks organized. Basically, all they had in African American communities in the county was the NAACP.21 For many African Americans in the county, then, black power never made significant inroads.

In general, black power never gained the popularity and mass appeal of soul. Black power advanced soul ideology because it championed the study of African culture and the development of a black consciousness. It also encouraged African Americans to imitate the black power movement’s example of adopting Africanisms: African dress, natural hairstyles, soul music, and soul food. Black power proponents argued that for too long white society had been declaring that African American culture was not worthy of respect. In reaction, African Americans sought to develop a new cultural identity through soul that would unite and guide the black power movement. Before the country could be changed, however, the African American community had to redefine its cultural values and reject white acculturation. Like wearing African attire or sporting an Afro, eating soul food in the 1960s and 1970s represented a political statement for those with a new black consciousness, “a declaration of the right,” writes Rustin, “and the necessity to be different.”22

SOUL

In the 1960s and 1970s soul became the requirement for entrance and acceptance in African American communities. At the same time, soul helped upwardly mobile and assimilated African Americans stay connected with their roots after their migration to largely white suburban communities. Civil rights activist Bayard Rustin argues that the “soul renaissance” challenged college-educated African Americans with mobility to “say no” to the impulse to assimilate into white society and thus forfeit their blackness. It deified black church culture, natural hair, ghetto life, black music, and soul food. In Rustin’s words, it was the sudden discovery that “black is beautiful and that white is not necessarily right; it was a card of identity, a pass key to a private club, a membership in a mystical body to which Negroes belonged by birthright and from which whites for a change were excluded by the color of the their skins.”23

Soul ideology from the 1960s also maintained that African Americans had hard-earned experiential wisdom that came from growing up black in America. That is, through years of surviving racism in the Americas, people of African descent had developed a natural instinct and intuitive understanding of how to make something wonderful out of the simple or out of what wealthier folks claimed had no apparent value. In the same vein, soul intuition informed African American cultural productions such as dress, music, and food. Soul is a hunch about what is good in a racist society that defines most cultural productions associated with black folk as inferior. Soul intuition is an African American trait that developed as Africans negotiated the Atlantic slave trade, slavery, and jim crow. It served black people as a necessary collective consciousness developed largely out of the limited resources that white society granted African American people who were forced to adapt to ghetto environments.24

In the early 1960s business owners in northern black communities like Harlem utilized soul vocabulary to attract black customers. But soul was not just a commercial creation. African Americans in northern inner-city neighborhoods started identifying with the poor man’s music and food that they enjoyed and reminded them of their southern roots according to “race rather than region,” writes one sociologist.25

Alton Hornsby, Jr., grew up in southeast Atlanta in the 1940s and 1950s. Back then, black people didn’t talk about soul food. “They would just say chitlins, pigs’ feet, southern fried chicken, etc., [and] barbecue, just things that black folk ate and some white folk.” He goes on to say, “I don’t remember the term ‘soul food’ coming into such popularity until about the same time as the early phases of the civil right movement. . . . Then it was being referred to as soul food and also soul music. We used to call it rock and roll. Then about that time the names ‘soul food’ and ‘soul music’ began to be used more commonly.”26

Thus, starting with the 1960s, urban dwellers in cities like Atlanta gradually made the transition from talking about rock music (rhythm and blues) and southern food to calling it soul music and soul food. In the face of the ethnic diversity of northern cities, soul became associated with African American culture and ethnicity. People with soul had a down-home style that migrants from the rural South could unite around. For this working class, composed predominantly of underemployed urban dwellers, soul made them members of a special group of cultural experts. Soul gave them privileges in a racist society that denied them opportunities, and it emerged as a counterculture that undermined white authority.

African Americans took the common knowledge about how to cook and eat soul food as a source of collective identity. Soul food, like soul music, represented another example of the subculture that served as an exclusive African American club, off limits to those who did not live the black experience. The use of soul food as part of the black experience becomes difficult, because there is no single black experience, just as there is no one type of soul food. Descriptions of soul food from the 1960s and 1970s illustrate this point.27

SOUL FOOD DEFINED

Some argue that soul food is basically southern food. “I don’t know any of those so-called soul food items that southern Euro-Americans particularly did not eat,” says Alton Hornsby, Jr., who has spent his life in Atlanta, Georgia, with the exception of short stints in Nashville, Tennessee, and Austin, Texas.28 Natives of the black belt region of Alabama and South Carolina (born in 1933 and 1928, respectively) make similar observations.29 Interviews reveal that differences in cuisine are more regional than ethnic; black and white folk in the South ate according to essentially African American-shaped culinary traditions formed over hundreds of years. The differences in eating habits are greater between northerners and southerners of any race than between white and black southerners.30

Ella Barnett, for example, a professional caterer for over fifty years in Westchester County, observed that the food requests from white and black clients were very different.31 According to the 1930 census records, however, at that time most of the county’s African American population had been born in the South or raised by one or more parents born in the South. In contrast, most of the white population had been born in the North, born in Europe (Italy, Ireland, Eastern Europe), or raised by one or more parents that were European.32

Over the years, Barnett found that her white clients “didn’t know nothing about soul food” and “never had anything like that.” It was her African American clients that wanted a “little bit different” kind of cooking: “Black folks want pigs’ fit [sic] and chitlins and stuff like that.” Soul food, says Barnett, is “black folk’s food, that’s what I call it.”33 Reginald T. Ward, Joseph “Mac” Johnson, and Clara Pittman all define soul food as the “food that you were brought up on.”34

A part-time caterer and superb cook of southern cuisine, Reginald T. Ward left Robinsonville in Martin County, North Carolina, the day after graduating from high school in 1962. “In my hometown there was no work,” he said. “I graduated from high school on a Wednesday, and on Thursday I was gone.” He first migrated to California to attend UCLA. After completing school, he migrated to the southern Westchester city of Mount Vernon, where his brother lived. His brother had left for New York years before, taking a room in a boardinghouse owned by women who had previously lived seven miles from the Wards’ home in North Carolina. “We all had friends that lived in our town that migrated to Mount Vernon,” says Ward. “Some of the kids that I grew up with were living there at the time.” He asserts that soul food was food that they had all enjoyed as children in North Carolina. It was food that had “flavor and taste.”35

Joseph “Mac” Johnson was born in Banks, Alabama, in Pike’s County, in 1933. He is a retired professional cook and restaurateur living in Poughkeepsie, in Dutchess County, New York. During World War II, his father had migrated to Poughkeepsie to work in an elevator factory and sent money home to his family, who were tenants on a dairy farm. Mac went into the military after high school and worked as a cook. After his tour, he took a job as a dishwasher for the state of New York at the Hudson River Psychiatric Center in Poughkeepsie. By 1952 he was the head cook at the center. He went to school and advanced to a position at the Bureau of Nutrition Services, among other jobs for the state of New York. From 1966 to the 1980s he operated a very profitable take-out-only venue, simply called Joe’s Barbecue, that specialized in chopped barbecue and other southern soul food dishes. Posting only professionally made signs and menus, requiring his employees to wear uniforms, and keeping the barbecue stand spotless, Johnson successfully marketed southern food to both black and white customers.36

According to Johnson, soul food is inexpensive food that is “seasoned so good that it fascinates you.” He adds, “I am seventy-two years old, the things that they sell now you could go to the slaughter house [in urban areas of Alabama] and they would give them to you. Pigs’ feet, they would give to you, spare ribs,” and chitlins. “So you had to learn to cook those things.”37 Interestingly, when the food industry started marketing southern African American cookery such as soul food in the 1960s, supermarkets started putting “their soul food on display in frozen packages, cellophane-wrapped bags, and instant-mix boxes,” writes an author in a 1969 article published in the African American magazine Sepia. In the late 1960s whites in the food industry began making money off soul food after years of laughing at the black women who collected the hogs’ ears and pigs’ feet that slaughterhouses and butcher shops discarded. “Your corner A&P right now may be stocking boxes and bags and cans of prepared soul food,” says the article in Sepia, “guaranteed authentic, no doubt, by a Soul Housekeeping seal-of-approval.”38

Clara Pittman, who grew up in Pinehurst, Georgia, and St. Petersburg, Florida, agrees with Ward and Johnson’s definition of soul food. She says that before soul food became profitable for grocers, when she was growing up in the 1950s, it “was basically all the food that blacks had to eat. It was the least expensive and the only food they could afford to buy.” She adds, “I would say on average of three or four days a week you had either necks, bones, or chitlins, or pigs’ feet, with some greens, or some type of corn bread or biscuits or whatever.”39

In the city of Mount Vernon, New York, North Carolinian Reginald Ward remembers that in the 1960s he and fellow southerner Eugene Watts survived on similar kinds of inexpensive meals prepared at a restaurant called Green’s Royal Palm. According to Ward, that place “kept me and Gene alive!” Like Gene Watts, the owner of Green’s Royal Palm was a migrant from Virginia. “We went there every morning, every day, because it was what we could afford,” says Ward. “Everything he had was affordable. He had fatback and biscuits, with a cup of coffee would have cost you about sixty-five cents.” Ward adds, “The biscuit was huge! Then he made chicken gizzards and chicken necks in a stew over rice.” A large serving of the stew and rice filled you up, and it only cost about $1.50.40 Alton Hornsby of Atlanta argues that economics reasons might have caused black southerners to eat more of what today we call soul food items in larger quantities than did white southerners, but every poor person struggling to survive ate soul food on a regular basis.41

It was during the civil rights and black power movements of the 1960s that the survival food of black southerners became the revolutionary high cuisine of bourgeoisie African Americans. Writing in 1968, Eldridge Cleaver said “ghetto blacks” ate soul food out of necessity while the black bourgeoisie ate chitlins and such as a “counter-revolutionary” act that mocked white definitions of fine dining.42 For example, in 1969 a writer for the Chicago Defender, a black newspaper, described soul food as high cuisine, a “blend of the best traditional cookery of Africa, Spain, France, and the American colonies to which Negroes added their knowledge of culinary herbs.”43 Cleaver scoffed at the glorification of soul food. Black folks in the ghetto “want steaks. Beef steaks.”44

BLACK INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS

The black power movement and the glorification of distinctively black culture inspired the emergence of the black arts movement of the 1960s. One of the leading figures in the black arts movement, Amiri Baraka, formerly LeRoi Jones, wrote about soul food in 1966 in his book Home: Social Essays. In an essay on soul food, he presented a rebuttal to critics who argued that African Americans had no language or characteristic cuisine. He insisted that hog maws, chitlins, sweet potato pie, pork sausage and gravy, fried chicken or chicken in the basket, barbecued ribs, hopping John, hush puppies, fried fish, hoe cakes, biscuits, salt pork, dumplings, and gumbo all came directly out of the black belt region of the South and represented the best of African American cookery. “No characteristic food? Oh, man, come on. . . . Maws are things ofays [whites] seldom get to peck [eat], nor are you likely ever to hear about Charlie eating a chitterling. Sweet potato pies, a good friend of mine asked recently, ‘Do they taste anything like pumpkin?’ Negative. They taste more like memory, if you’re not uptown.”45

In response to the black power and black arts movements, the first soul food cookbooks began to appear in progressive bookstores in the 1960s. Before then, largely white southerners had published cookbooks with instructions on how to make “southern dishes” like those Baraka described. These southern cookbooks, however, angered black chefs such as Verta Mae Grosvenor. An African American cook and writer originally from South Carolina, Grosvenor used her considerable cooking talents to raise money for organizations like SNCC. After she migrated to New York, she made a name for herself as a Harlem caterer and author during the black power movement.46

What bothered Grosvenor were white women like Henrietta Stanley Dull (home economics editor of the Atlanta Journal) who called themselves in their cookbooks “experts of southern cuisine.” The back cover of Dull’s Southern Cooking describes her as the “first lady of Georgia and the outstanding culinary expert in the South.” In response to the claim, Grosvenor argues that Dull’s book “ain’t nothing but a soul food cookbook with the exception that Mrs. Dull is a white lady and it is a $5.95 hardbook by a big publishing house.” Grosvenor was angry because white authors and publishers were profiting from an African American invention without compensating or acknowledging African Americans. “Cookbooks ain’t nothing but a racist hustle.” She adds, “It’s all about some money, honey, and if that ain’t so, how come it ain’t Carver Chunky Peanut Butter?” Grosvenor goes on to say, “We cooked our way to freedom, and outside of a few soul food cookbooks there has been no reference to our participation in, and contribution to, the culinary arts.”47

A few of the earliest contributions to the literature of soul food cookery provide insights into the black power roots of soul food. In the introductions to their cookbooks, several black culinary artists carefully describe, in distinctly black nationalist terms, what soul food is and what it most definitely is not, apparently in an attempt to patent and protect their intellectual property rights from the likes of the Dulls of the world. In his 1969 soul food cookbook, for example, southern-born African American Bob Jeffries emphasizes that soul food is not southern food in general. “When people ask me about soul food, I tell them that I have been cooking ‘soul’ for over forty years—only we did not call it that back home. We just called it real good cooking, southern style. However. . . not all southern food is ‘soul.’” He goes on to explain, “Soul food cooking is an example of how really good southern Negro cooks cooked with what they had available to them”; it’s about knowing how to season food to perfection. Jeffries argues that southern African American cooks “have always had an understanding and knowledge of herbs, spices, and seasonings and have known how to use them.”48

Returning to the theme of black invention and property rights, he goes on to say that “what makes soul food unique—and more indigenous to this country than any other so-called American cooking style—is that it was created and evolved almost without European influence.”49 In earlier chapters in this book, I argue against Jeffries’s black nationalist interpretation of soul food. Instead I argue that soul food is distinctively African American but was influenced by Europeans, who introduced corn to African foodways and then provided cornmeal, meat, fish, and other ingredients as rations to the first enslaved Africans in southern North America. In 1971 culinary writer Helen Mendes seconded Jeffries’s Afrocentric view of soul food in her book The African Heritage Cookbook. Soul food unites black Americans “with each other, and provides an unbroken link to their African past.” She adds, “At the heart of Soul cooking lay many elements of African cooking.”50

In A Pinch of Soul in Book Form, published in 1969, Pearl Bowser uses the words “our” and “us” throughout her description of soul food. I interpret this choice as signifying her belief that soul food is the intellectual invention and property of southern-born African Americans. It’s about how we somehow transformed “such things as animal fodder into rich peanut soup or wild plants into some of our favorite and tastiest vegetables dishes,” and it “represents a legacy of good eating bequeathed to us by our parents and grandparents,” who as slaves and later as sharecroppers “broke their backs but not their spirits.”51

According to Bowser, “Soul food is also food rich in taste. What is bland becomes exciting by the addition of our spices—garlic, pepper, bay leaf—and the other condiments which are always on the table along with the salt and pepper—hot pepper sauce, either from the West Indies or Louisiana, and vinegar to go on many meats and vegetables.” In another section of her book, she writes, “Our main meat source is still pork—fried, barbecued, roasted, smoked, pickled, spicy and hot.”52

RESTAURANTS AND SOUL FOOD IN THE LATE 1960S

Bowser and others writing in the late 1960s and early 1970s observed that the black power movement made soul food both fashionable and popular in urban restaurants. Bowser argues that it was the black power movement that gave black people a sense of pride about their food. In addition, the message of black power inspired people like her to write soul food cookbooks: “There was a time when soul food could be had only at home or when provided by the church sisters. It certainly never appeared in print and was seldom referred to with pride, however much it was enjoyed. Its emerging popularity is due not only to its significance as a remembrance of things past but also as an affirmation that black is beautiful.”53

Black power also inspired restaurateurs to put soul food on their menus. An article in Sepia confirms the growing popularity of soul food. Published in 1969, the article says, “Soul Food is so ‘in’ these days that restaurants all over the right neighborhoods are featuring it. But now restaurants in many of the wrong neighborhoods are opening up to serve soul food too. . . . Soul food is ‘in’ and wouldn’t you know it, the price has gone up as the demand has soared.” The article goes on to say, “Four bits used to get you a meal in lots of restaurants if you didn’t mind a cracked plate and no tablecloth. The menu was scratched fresh everyday onto a blackboard and your choice was typically either chicken or ox-tail served up with greens and rice. For an extra dime you could have a piece of fresh homemade sweet potato pie. Now that such substantial eating has been dubbed ‘soul food’ it’s started moving downtown—and the prices are moving up.”54

Notable African American celebrities in the 1960s invested in shortlived attempts to sell soul food restaurant franchises. Starting in 1968, gospel recording artist Mahalia Jackson sold a Chicken Store franchise that sold “mouth-watering southern fried chicken along with catfish, sweet potato pie and hot biscuits.” James Brown entered into a similar venture franchising Gold Platter soul food restaurants all over the country. The “menu at the look-alike chain outlets will feature chicken with French fries, cole slaw and cornbread; catfish with hush puppies; or less cultured hamburgers and cheeseburgers. Everything is to be served up, of course, on a gold platter just like the sign out front.” Muhammad Ali got into the act too, with a franchise of restaurants that featured what he called the “Champburger.” Starting in Miami, Ali hoped to start a chain of black-owned-and-operated Champburger Palaces in black neighborhoods. “In addition to the Champburger, the establishments also will sell hot dogs, fried chicken, fried fish, boiled fish, other food products and soft drinks.” Southern-born blacks, however, argued that Ali’s Chamburger palaces were not serving soul food.55

REAL SOUL FOOD

Debates over soul food were common on the streets of New York City and other cities. Northerners and southerners just did not agree on the definition of soul food. Southerners complained that much of the food advertised as soul food by restaurants was not soul food at all or was “more Southern than soul.” “To people who just do not know better,” wrote Bob Jeffries, it means “only chicken and ribs, corn pone, collards, and ‘sweet-taters,’ but nothing could be more authentically soul than a supper of freshly caught fish, a fish stew, or an outdoor fish fry.”56 Southerners in New York argued that, for real soul food, you had to stand in line at Harlem restaurants like the Red Rooster, Jock’s Place, and Obie’s, where they sold trotters, neck bones, pigs’ tails, smothered pork chops, black-eyed peas, candied yams, and “grits ’n’ eggs.”

For many, soul food was difficult to describe because it was all wrapped up in feelings. “Soul food takes its name from a feeling of kinship among Blacks,” wrote Jim Harwood and Ed Callahan, who coauthored a soul food cookbook. It is “impossible to define but recognizable among those who have it.” Similarly, Harlem restaurant owner and cook Obie Green, who, like James Brown, was a native of Augusta, Georgia, insisted that soul is cooking with love. “And I cook with soul and feeling.” Bob Jeffries, also a southerner, argued that soul food was down-home food “cooked with care and love—with soul.”57 South Carolina–born culinary writer and cook Verta Mae Grosvenor also makes the argument that the right feelings are essential to making soul food, “and you can’t it get [them] from no recipe book (mine included).” She insists that a good cookbook does not make a good cook. “How a book gon tell you how to cook.” It’s what you “put in the cooking and I don’t mean spices either.” Jeffries also agreed that soul food was made without recipes; it was made with inexpensive ingredients that “any fool would know how to cook” if they grew up eating it.58

Soul food, then, according to black cooks, is an art form that comes from immersion in a black community and an intimate relationship with the southern experience. Soul food originated in the quarters of enslaved Africans in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. It is a blend, or creolization, of many cooking traditions that Africans across the Americas seasoned to their own definition of perfection with their knowledge of culinary herbs gained from their ancestors. Soul food was spiritual food because some dishes were served only on Sundays and other special days during slavery and thereafter.

It was simple food, yet it was often complex in its preparation. Soul food required a cook with a good sense of timing of when to season, how long to stir, mix, fry, boil, sauté, bake, grill, dry, or smoke an ingredient and how to cut, skin, dip, batter, or barbecue. Without timing and skill, a cook had no soul worth talking about. Soul food was nitty-gritty food that tasted good and helped African Americans survive during difficult times. For a long time, none of its ingredients came in a can or box, and thus soul food was free of artificial preservatives. Oral history based on African folkways ensured that cooks passed on recipes from one generation to the next, and recipes and cooking techniques developed out of a common black experience and struggle with racism. Summing up reflections and commentaries on soul from the black power era, I have been able to formulate six statements about and working definitions for soul food:

Soul is a cultural mixture of various African tribes and kingdoms

Soul is adaptations and values developed during slavery and emancipation

Soul is the style of rural folk culture

Soul is the values and styles of planter elites in the Americas

Soul is spirituality and experiential wisdom that make black folk unique

Soul is putting a premium on suffering, endurance, and surviving with dignity

During the 1960s and 1970s a somewhat heated debated developed between three camps within the African American community: African American intellectuals who argued that soul food was uniquely part of black culture and therefore the intellectual capital of black folk; white intellectuals who insisted that soul food was a southern regional food that belonged to southerners; and members of the Nation of Islam, advocates of natural food diets, and college- and university-educated African Americans who argued that soul food was nothing to be celebrated or guarded as their own because it was killing black folks. I discuss the last school of thought in the final chapter, when I turn to critics of soul food and movements advocating natural food diets. But before that, in the next chapter, I turn to a look at the history of Caribbean influences on soul food and urban identity.