Not surprisingly, leadership is the soul builder of a Lean Business System. Leadership tends to be a topic that everyone understands at an intellectual level, but has difficulty practicing effective leadership on a daily basis. Furthermore, the composition of executives’ leadership style is largely a function of what they achieved in the past that enabled them to rise to their positions. Many executives have reached the executive suite because of subject matter knowledge rather than leadership expertise. This chapter is not about bashing leadership for a failed fad improvement program, because everyone is only human. Besides, this excuse is not the real root cause; it is symptomatic of deeper conflicting and misaligned issues in the organization. It’s a cop-out to suggest that everything is leadership’s fault and that the buck stops there because this destructive thinking prevents organizations from turning that axiom buck into millions of real bucks!

Today many organizations are constrained by a leadership style that is outdated. To be candid, it’s apparent that Western leadership is based on a combination of military organizational theory, principles of scientific management, and short-term financial performance. When leadership limits itself to hitting the numbers each month, it creates a false sense of success. Great organizations hit the numbers, but they also build high-performance organizations with a high-performance culture composed of high-performance people, talent, and skills. This style of leadership enables organizations to keep hitting the numbers because all associates are hunting down and eliminating the wastes that increase the risk of not hitting the numbers. Culture is deliberate—it is difficult to transform and easy to reverse direction of basic core values. Leadership has been talking a good game about engagement and empowerment for decades, but the majority of organizations have yet to leverage the knowledge and skills of their associates. This chapter is about evolving traditional leadership in order to achieve continuous renewal and associate engagement top down, bottom up, middle out, and laterally. Leadership for adaptive systematic improvement must originate from as many sources as possible in the organization. This is engagement and empowerment—for real and is living every day.

Being a leader is not an easy job in today’s fierce global economy. Executives are constantly challenged and surprised at all the issues they must face, always operating at extended bandwidth mode. Many executives got to where they are because they were great at getting things done in their particular area of subject matter expertise. Executives can no longer make the same amount and type of decisions they have made in the past because the content is too complex and cannot be resolved by immediate actions taken by a single individual. Leadership must engage the entire organization in decision making and improvement. We are not insinuating that the shipping clerk develop the company’s marketing plan. But we are insisting that organizational engagement is influenced significantly by leadership: executive behaviors, choices, actions, how they scan for opportunities, how they mentor and grow their organizations, how they communicate, how they balance the needs of multiple stakeholders, how they run interference, how they achieve goals through the positive engagement of others, and how they achieve the success of the whole enterprise. One of the best references on organizational engagement is contained within Disney Great Leader Strategies. This reference demonstrates that leadership starts top down to set the objectives and direction. Then leadership evolves to a very powerful hybrid of highly skilled, engaged, and empowered associates that live and breathe horizontal, vertical, lateral, bottom-up, top-down, and middle-out leadership. Great leadership comes from all directions when it develops and engages talent. When you ask for help from one of the Disney associates, you always get your questions answered on the spot. You never get a “Please hold” or, “I’m not sure,” or, “Let me speak to my manager.” Disney understands how to manage customer touch points and deliver the superior customer experience.

This chapter stresses the importance of this type of leadership in a systematic process of improvement, and provides a systematic model of leadership (Adaptive Leadership) to create new breakthroughs in operating performance. Why is leadership so important? Because organizations naturally adapt to the personality of a CEO and his or her executive team through their behaviors, choices, and actions. Leadership shapes culture, harmony, productivity, and in general how their associates think and work. Engagement and empowerment are crucial to this process because they develop associates who are customer-friendly, ambitious, motivated, enthusiastic, happy, intelligent, polite, respectful, conscientious, honest, curious, high energy, collaborative, and focused—and many more positive adjectives. There are no Cliff Notes for this stuff; it is a learned and developed competency. In a Lean Business System, organizations are challenged to develop Disney-like talent that has no fear of discussing or fixing problems on the spot. Such organizations have employees with the skills and talent to identify new opportunities, and they have a culture that engages people where they work, encouraging associates to proactively respond to problems and new opportunities. In short, adaptive systematic improvement evolves to become a 360-degree process.

Back in the 1970s a concept called management by wandering around was popular. It returned in the 1990s as going to the gemba. In Western organizations many of these efforts have turned into informal visits to talk to employees and get a better understanding of what is going on at a daily microlevel. For some people it literally became wandering around, kibitzing with employees about everything but improvement and going through the motions for their superiors. By the way, this is but another example of blindly copying a standard Lean or TPS practice and missing the technical discipline, culture, and spirit that makes it work. We mentioned previously with technology and changing process structures that we are all connected to the gemba 24/7. In a well-functioning adaptive systematic management process, leadership must evolve and integrate this concept so that it becomes more of a continuous and formal scanning of the external competitive world as well as a scanning of the internal culture and a response to this competitive world. It is a very formal, structured, disciplined, and fact-based leadership process of always looking for new opportunities and always looking at how to build a more robust, culture-enabled organization. It is a process of everyone using structure and discipline, hunting for the next opportunity.

There is no room for complacency, procrastination, postponement, or confusing priorities in a systematic process of improvement. These actions are organization killers in this economy. Why? Because they breed Maladaptive Leadership and a cultural mode that inhibits the ability of executives and their organizations to adjust to particular changing situations. Maladaptive Leadership shuts down formal and structured improvement. It promotes avoidance, denial, reactionary efforts, working harder instead of smarter, emergency hot list meetings, and other similar behaviors that might create activity and reduce the immediate anxiety of a problem. However, the result is dysfunctional and non-value-added, and it does not alleviate the actual problem in the long term. In fact, this cultural condition typically increases the size of the main problem, creates other new interrelated problems, and demotivates an already confused and overloaded organization. A common outcome in these environments is the separation disorder of improvement where improvement is perceived (and allowed) to be in addition to rather than an integral part of daily work. Maladaptive Leadership drives culture backwards and cultivates the negative traits of helplessly overloaded resources, political motivations, dishonesty, loss of interest, protectionism, lack of risk, concealment of problems, lack of trust, loss of caring and loyalty, disinterest in the next silver bullet program, and associates who are just putting in their time to name a few. Organizations can never expect to become best in class with this kind of culture—no matter how many improvement programs, tools, and Lean or TPS jargon they throw into the mix.

There is an explanation of why some organizations are successful year after year while other seemingly extraordinary companies eventually fall by the wayside. It comes down to a cohesive executive team that understands how to systematically conceive, lead, and continually rediscover innovation, growth, improvement, and change management throughout their business life cycles. It is becoming increasingly more difficult to sustain competitiveness and superior performance, especially with the same course of action and talent pool. For organizations that get temporarily lucky, their success does not go unnoticed for too long in this economy. Success attracts competitors and imitators, so eventually maturity sets in and success becomes a commodity.

Superior competitiveness and operating performance can only be achieved with a deep-rooted adaptive systematic improvement culture—one that continually raises the bar for the organization and keeps the bar out of reach for competitors. This is the common underpinning in superior performing organizations: improvement as the cultural standard of excellence and expected code of conduct. Adaptive Leadership is the element that keeps the momentum of innovation, growth, improvement, and change management at superior levels of industry performance. Leaders are always at center stage in their organizations, sending formal and informal messages about what matters most. Constancy of purpose and constant two-way communication are very important to this process. Simply, Adaptive Leadership provides the moral compass and navigation system of adaptive systematic improvement.

Adaptive Leadership is the soul and spirit behind a systematic process of improvement. Adaptive Leadership serves as the permanent senior architects, operators, and sustainers of a systematic process of improvement. In the Lean Business System Reference Model™, leadership provides the harmony of this operating system through the integration of its interconnected subprocesses, and the lower-level interactive elements within each subprocess at any given moment in time. A closer look at this architecture clearly indicates that the scope includes total enterprise success, not just a good Lean manufacturing program. At the core of Adaptive Leadership are the executive values, vision, purpose, operating style, behaviors, and cultural attributes that create the right improvement Kata. These are the make-or-break factors on culture and adaptive systematic improvement. Let’s make sure that this is well understood: Leadership does not create this soul and spirit of an organization by launching the latest improvement program. Leadership is not following some standard linear recipe of instructions or mandating the use of improvement tools and copied practices, or encouraging a shibboleth of improvement jargon and sending everyone off on ritual gemba walks. Leadership’s primary role is to create an organizational environment for success (i.e., vision, purpose, strategy, core behaviors, and cultural expectations). Leaders also nurture themselves and their organizations through the creative human development practices of learning to learn, learning to observe, learning to coach, and learning to develop culture. These unified factors in turn nurture organizational experiences and create an evolving cultural standard of excellence—the right, higher-order improvement Kata as the foundation of a Lean Business System.

The soul and spirit of a systematic process of improvement are living and essential phenomena. Figure 3.1 provides a graphic overview of Adaptive Leadership. It is the leadership mechanisms behind this style of leadership that are important to understand.

Figure 3.1 Adaptive Leadership

Copyright © 2015, The Center for Excellence in Operations, Inc.

In the center and right side of the figure is the Adaptive Leadership mode. The figure illustrates leadership cycles through stages where their organizations hit natural performance plateaus. Enlightened leaders recognize these performance plateaus immediately and either modify the current course or rediscover a totally new course through a continuous cycle of reckoning, renewal, and enlightenment. In effect, their leadership behaviors, choices, and actions prevent performance plateaus and other disruptions to improvement. Reckoning is the immediate recognition of the need to change course, and renewal is the vision and execution of change to a higher level of excellence and performance. Enlightenment is the positive outcome of this successful, continuous cycle of reckoning and renewal. This continuous cycle transforms improvement from another wish or short-lived program into a long-term cultural standard of excellence. Enlightened leaders know when to make minor adjustments and when bolder changes in direction are necessary. They are decisive and armed with the facts. They make the right tough decisions swiftly. They involve themselves from strategy to execution to make sure that there is continuity of purpose and that strategy and plans are executed swiftly and are on point. They use a balanced scored approach to performance management and expect the same cascading standard through their organizations. They maintain the continuous in continuous improvement.

Adaptive Leadership relies on executives who understand the importance of a combined strategy of Deming’s back to basics and other timeless fundamentals; innovation and creativity; the integration of enabling technology, and adaptive improvement across diverse industries and environments. Adaptive Leadership creates an environment of near real-time “fast forward improvement” called SIDAM (sense, interpret, decide, act, monitor). It also leads to business model innovation through improvement. The more executives think “beyond the box,” the better they and their organizations become at discovery and innovation.

Adaptive Leadership is the future of leadership: a style of leadership excellence that is timeless because it continuously develops leadership talent and organizational competencies in both current and future-focused time horizons. This style of leadership replaces the traditional life cycles of discrete leadership stages with one of continuous cycles of leadership and discovery. Adaptive Leadership continuously strives to achieve a more holistic form of greatness that goes way beyond the self. The best-in-class Lean and continuous improvement organizations get it and fully understand that short-sighted, reactionary leadership is not sustainable in the new economy. Leaders who allow themselves and their organizations to twirl and toss in the modes of insanity and hyperinsanity are not innovating their business models and creating the business conditions and cultures that will lead to continuous future successes. Executives and their organizations need to figure out very quickly how to spend all their time in the reckoning, renewal, and enlightenment areas of our model. This is the essence of a Lean Business System, as well as everything else an organization does to become a great organization with great people.

The lower left region of Figure 3.1 is a leadership trap for many organizations. The figure illustrates two distinct cycles of leadership:

Insanity. “Doing more of the same and expecting different results,” which is usually followed by a more acute cycle of hyperinsanity.

Insanity. “Doing more of the same and expecting different results,” which is usually followed by a more acute cycle of hyperinsanity.

Hyperinsanity. “Doing more of the same with greater urgency and velocity, and expecting different results.”

Hyperinsanity. “Doing more of the same with greater urgency and velocity, and expecting different results.”

These styles of leadership are very common in organizations today because there is so much to accomplish in so little time, and people are stretched beyond their bandwidths. Additional work keeps arriving on people’s plates, but nothing is being removed from their plates. Leadership is not: “Do the best that you can,” “Try harder,” and “Just figure it out.” Figure 3.1 shows an area that we call the maladaptive zone. The insanity and hyperinsanity cycle occurs when leaders choose to “rabbit” themselves and their organizations around from one crisis to the next. Everyone knows that this approach is incorrect intellectually, yet many leaders give in to immediate reason: the act of attempting to correct a situation at hand with unreasonable actions based on opinions, perceptions, or direct orders from others who are missing the facts. The objective is instant gratification. This certainly does not achieve Deming’s point about continuity of purpose, and often these efforts create bad improvement Kata and a demoralized organization. When leadership becomes an activity of managing one crisis after another and puts too much focus on short-term revenue and profits, executives quickly lose sight of the bigger picture. They lead by and perpetuate a “whack-a-mole” style of leadership in their organizations, and this style of leadership is more common than most executives and managers would like to admit. Executives cannot continue to do the same things and expect to achieve different results. Too many organizations are stuck in this vicious cycle of insanity and hyperinsanity and risk falling behind in this challenging economy. Constancy of purpose is dealing with uncertainty in a more adaptive equilibrium state. Adaptive Leadership is about shutting down these large reactive pendulum swings in leadership behaviors, choices, and actions that appear to correct symptomatic issues in one direction while creating more and larger problems in the opposite direction.

The process of reckoning, renewal, and enlightenment is the center point of Adaptive Leadership. To refresh the reader’s memory:

Reckoning is the immediate recognition of the need to change course. Reckoning is not a negative activity; it is a reflection of successes, mistakes and misdeeds, and emerging issues facing the organization. Without reckoning, organizations cannot plan for change and improvement. Reckoning formally defines the gaps between current performance and desired performance over various time horizons. Managers are forced to deal with change after it hits. We have already discussed the results: insanity and hyperinsanity.

Reckoning is the immediate recognition of the need to change course. Reckoning is not a negative activity; it is a reflection of successes, mistakes and misdeeds, and emerging issues facing the organization. Without reckoning, organizations cannot plan for change and improvement. Reckoning formally defines the gaps between current performance and desired performance over various time horizons. Managers are forced to deal with change after it hits. We have already discussed the results: insanity and hyperinsanity.

Renewal is the vision and execution of change to a higher level of excellence and performance. Renewal is the process of developing the right improvement strategy and tactics to keep the systematic process of improvement alive, further develop the organization’s talent, and achieve superior industry performance.

Renewal is the vision and execution of change to a higher level of excellence and performance. Renewal is the process of developing the right improvement strategy and tactics to keep the systematic process of improvement alive, further develop the organization’s talent, and achieve superior industry performance.

Enlightenment is the positive outcome of this successful, continuous cycle of reckoning and renewal. Enlightenment covers the full cycle from idea to execution and standardization of an improved process. One cannot feel enlightenment from the idea alone. Enlightenment is experienced by the full success of improvement.

Enlightenment is the positive outcome of this successful, continuous cycle of reckoning and renewal. Enlightenment covers the full cycle from idea to execution and standardization of an improved process. One cannot feel enlightenment from the idea alone. Enlightenment is experienced by the full success of improvement.

The big question in all of this is, “How do I and my executive team, managers, and entire organization adapt this approach to leadership?” Figure 3.2 provides an overview of this process.

Figure 3.2 Reckoning, Renewal, and Enlightenment

Copyright © 2015, The Center for Excellence in Operations, Inc.

Adaptive Leadership is based upon the principle of inclusion. Executives cannot go through all the details of reckoning, renewal, and enlightenment on their own. Adaptive Leadership also includes creating a safe, collaborative workplace ecosystem that nurtures trust, mutual understanding, continuous coaching and development, and total freedom of expression. Inclusion builds a culture that invites total participation, engagement, multiple perspectives, and contribution to holistic success. The very first step is invisible and not shown but it is the toughest step. It’s often painful for executives to come to the realization that what they have been doing isn’t working anymore. Many might feel the emotions of this realization as a personal reflection on their leadership competence. The entire organization shares this pain. The pain increases the longer executives and their organizations remain in the same situation. This first step involves rethinking the journey. Recognition of the need to change is a healthy leadership discovery; it is how good leaders grow to become great leaders.

Adaptive Leadership is state-of-the-art leadership that requires a combination of process and technology, namely:

Organizational scans that include both an internal and external check-in on the organization’s health and well-being of the business as a whole. Organizational scans are continuing disciplined processes and include two categories: the business scan and the cultural scan. The business scan is a structured operations due-diligence activity, while the cultural scan is a status and needs update on the human capital side of the business. These continued scans are the basis for identifying new business and cultural requirements and for feeding our Lean Business System Reference Model with laser-targeted, high-impact improvement opportunities.

Organizational scans that include both an internal and external check-in on the organization’s health and well-being of the business as a whole. Organizational scans are continuing disciplined processes and include two categories: the business scan and the cultural scan. The business scan is a structured operations due-diligence activity, while the cultural scan is a status and needs update on the human capital side of the business. These continued scans are the basis for identifying new business and cultural requirements and for feeding our Lean Business System Reference Model with laser-targeted, high-impact improvement opportunities.

A formal analytics support system that integrates the scanning processes above with technology; namely, business analytics. Technology enables the continuous iterative exploration and investigation of prior business performance and helps executives to gain insight into future business requirements and competitive issues. Business analytics provide the data-driven and fact-based view of the business and its challenges. There are several types of business analytics methods that answer questions like what is the current state, what happened, how many, how often, where the problems exist, and what actions are needed. Business analytics can answer questions like, “Why is this happening?” “What if these trends continue?” “What will happen next?” and, “What is the best that can happen?”

A formal analytics support system that integrates the scanning processes above with technology; namely, business analytics. Technology enables the continuous iterative exploration and investigation of prior business performance and helps executives to gain insight into future business requirements and competitive issues. Business analytics provide the data-driven and fact-based view of the business and its challenges. There are several types of business analytics methods that answer questions like what is the current state, what happened, how many, how often, where the problems exist, and what actions are needed. Business analytics can answer questions like, “Why is this happening?” “What if these trends continue?” “What will happen next?” and, “What is the best that can happen?”

The business scan is a formal methodology used for conducting a diagnostic and assessment of the organization’s strengths and weaknesses relative to competitors and emerging market opportunities. The purpose of this scan is to identify gaps between current operating performance and where the organization needs to be in order to remain a superior player in its industry.

The business scan is a four-step process:

1. Review the business strategy and operating plan: This is a review of goals rather than current operating performance. Its purpose is to identify specific gaps between current and desired performance. The result of this step is the identification of high-level improvement themes, which are later detailed in specific, assignment-ready, improvement activities in step 4.

2. Benchmark the organization’s current and potential performance against relevant best practices and demonstrated best-in-class performance: The purpose of this step is to identify how the organization is performing relative to inside industry and outside industry best-in-class organizations. Adaptive systematic improvement encourages organizations to learn from the experiences of others but adapt (not copy and paste) best practices to specific business requirements and culture.

3. Develop the adaptive systematic improvement strategy and implementation needs: This involves developing the Aligned Improvement Strategy, using the MacroCharter planning template.

4. Define improvement goals, benefits, and risks/consequences of not changing: This is the more tactical aspects of deployment planning, where the improvement themes are further detailed into specific, assignment-ready improvement activities, using the MicroCharter planning template.

The diagnostic reveals both current inefficiencies and future business requirements. It also provides the working road map for a successful systematic process of improvement because it provides the up-front, deep-core drilling into the organization’s key strategic, business, and operations issues.

The cultural scan is a check-in on the organization’s readiness and willingness to change. It is designed to surface any people issues, frustrations, opinions and perceptions, communication issues, political issues, or other human resource issues that may become detractors to improvement. The cultural scan is checking the vital signs of Kata—the behavioral and cultural development needs. Many organizations conduct periodic internal scans through formal surveys, structured evaluations, focus groups, town hall meetings, functional area meetings, or some combination thereof. The aim is to continually identify how the organization can support its associates and help them in any way to operate in a safer, productive, and positive environment. The internal scan determines the organizational and cultural alignment with the organization’s intended strategic goals and improvement plans.

Some of the results from a cultural scan that are very necessary to adaptive systematic improvement include but are not limited to the following areas:

Communication and reinforcement of mission/vision/purpose.

Communication and reinforcement of mission/vision/purpose.

Understanding the corporate values communicated compared with those actually practiced.

Understanding the corporate values communicated compared with those actually practiced.

Organizational structure and reporting relationships, and how these might impact associates’ abilities to get things done.

Organizational structure and reporting relationships, and how these might impact associates’ abilities to get things done.

Code of conduct assessment—real or symbolic.

Code of conduct assessment—real or symbolic.

Personal growth and career and talent development plans.

Personal growth and career and talent development plans.

Adjustments to leadership and management behaviors, choices, and actions.

Adjustments to leadership and management behaviors, choices, and actions.

Management practices, degree of command versus empowerment.

Management practices, degree of command versus empowerment.

Individual, group, and department issues and barriers to success.

Individual, group, and department issues and barriers to success.

Communication issues.

Communication issues.

Overall climate and attitudes in the organizations.

Overall climate and attitudes in the organizations.

Effectiveness or inefficiencies in policies and procedures.

Effectiveness or inefficiencies in policies and procedures.

Progress with systems and key business processes.

Progress with systems and key business processes.

Performance measurement systems.

Performance measurement systems.

Workplace environment and conditions; safety issues.

Workplace environment and conditions; safety issues.

An assessment of the executive leadership team and key organizational positions, talent backstops, the organization’s abilities to implement new strategic improvement initiatives, and additional talent and skill development needs are also part of the cultural scan.

The new requirements of organizations are evolving at a much faster rate than can be identified and responded to—especially in a manual world. Business analytics allows for the efficient exploration and investigation of current conditions, performance gaps, and strategic and operating needs. Developing an analytics support capability for a Lean Business System is not a big deal or a year-long IT project. For simplicity and clarification, business analytics can be grouped into the following types of information:

Intelligence analytics is information that provides a continuous snapshot of what is going on in a business. Real-time, digital performance dashboards and data visualization technologies that display metrics and other graphical information are examples of intelligence analytics. The objective is to get everyone on the same page in terms of current conditions and issues.

Intelligence analytics is information that provides a continuous snapshot of what is going on in a business. Real-time, digital performance dashboards and data visualization technologies that display metrics and other graphical information are examples of intelligence analytics. The objective is to get everyone on the same page in terms of current conditions and issues.

Descriptive analytics is like descriptive statistics. Information is analyzed by predetermined methods and displayed in various tabular or graphical summaries (e.g., averages of customer fill rates by product, Pareto analysis of revenue and profit contribution by product, customer, territory, and so on. The objective is to break down obscure data into smaller attributed clusters through statistical profiling, segmentation, and other statistical means.

Descriptive analytics is like descriptive statistics. Information is analyzed by predetermined methods and displayed in various tabular or graphical summaries (e.g., averages of customer fill rates by product, Pareto analysis of revenue and profit contribution by product, customer, territory, and so on. The objective is to break down obscure data into smaller attributed clusters through statistical profiling, segmentation, and other statistical means.

Diagnostic analytics is a deeper dive into information with more advanced statistical engineering techniques to better understand cause-and-effect relationships in performance data. Diagnostic analytics strives to identify and explain the relative influence of root causes on a particular business outcome. For example, what are the primary drivers of delivery performance or pipeline inventory performance or product quality or late time to market? These are known problems.

Diagnostic analytics is a deeper dive into information with more advanced statistical engineering techniques to better understand cause-and-effect relationships in performance data. Diagnostic analytics strives to identify and explain the relative influence of root causes on a particular business outcome. For example, what are the primary drivers of delivery performance or pipeline inventory performance or product quality or late time to market? These are known problems.

Discovery analytics involves advanced inferential statistical tools like hypothesis testing, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and design of experiments (DOE). We start off with a pure “we don’t know what we don’t know” condition. There exists perceptions, opinions, and speculation about corrective actions but we are normally dealing with issues that we have never been able to improve. These are unknown problems. Through the use of discovery analytics, the factors that most influence process performance can be isolated. It’s a discovery, because we discover problems and root causes with data and facts. If we solve this 20 percent of the root causes, we will eliminate 80 percent of the problem.

Discovery analytics involves advanced inferential statistical tools like hypothesis testing, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and design of experiments (DOE). We start off with a pure “we don’t know what we don’t know” condition. There exists perceptions, opinions, and speculation about corrective actions but we are normally dealing with issues that we have never been able to improve. These are unknown problems. Through the use of discovery analytics, the factors that most influence process performance can be isolated. It’s a discovery, because we discover problems and root causes with data and facts. If we solve this 20 percent of the root causes, we will eliminate 80 percent of the problem.

Predictive analytics usually involves simulations and modeling of future scenarios based on a predetermined set of assumptions. These assumptions can be modified to create a sensitivity analysis of what-if capability to analyze future scenarios or predict the outcomes of remaining in the same state. These are often complex and carefully structured statistical simulations in which the likelihood of certain outcomes are predicted based on various factors or input assumptions.

Predictive analytics usually involves simulations and modeling of future scenarios based on a predetermined set of assumptions. These assumptions can be modified to create a sensitivity analysis of what-if capability to analyze future scenarios or predict the outcomes of remaining in the same state. These are often complex and carefully structured statistical simulations in which the likelihood of certain outcomes are predicted based on various factors or input assumptions.

Prescriptive analytics is the summary of one or more other different types of business analytics. Once a situation is well defined and understood with data and facts, prescriptive analytics is useful in consolidating findings and conclusions, and in evaluating the feasibility and likelihood of success of various options or recommended courses of action (prior to taking physical actions). Prescriptive analytics is also useful in weighing the pros, cons, costs, barriers, and risks of various options.

Prescriptive analytics is the summary of one or more other different types of business analytics. Once a situation is well defined and understood with data and facts, prescriptive analytics is useful in consolidating findings and conclusions, and in evaluating the feasibility and likelihood of success of various options or recommended courses of action (prior to taking physical actions). Prescriptive analytics is also useful in weighing the pros, cons, costs, barriers, and risks of various options.

Optimization analytics is a higher order of predictive analytics that seeks to optimize process performance around conflicting constraints. The goal of optimization analytics is to either maximize or minimize a business given limited inputs (e.g., resources, capacity, capital, and other constraints). In these complex systems, these limited constraints are at conflict with each other for given situations. For example, how do we optimize the global supply chain? One answer is unlimited inventory, which is not feasible. Another answer might be to build more and larger production facilities or to spread our spend out to a hundred new suppliers or design reliable and defect-free products. I was involved with an optimization analytics study a few years ago in which the organization wanted to determine which metrics optimized profitability and EBITDA. Optimization analytics may produce a recommendation that minimizes operating costs or maximizes profitability, but keep in mind that one cannot possibly build all the factors in organizations (especially the unpredictable human factors) into these analytical exercises.

Optimization analytics is a higher order of predictive analytics that seeks to optimize process performance around conflicting constraints. The goal of optimization analytics is to either maximize or minimize a business given limited inputs (e.g., resources, capacity, capital, and other constraints). In these complex systems, these limited constraints are at conflict with each other for given situations. For example, how do we optimize the global supply chain? One answer is unlimited inventory, which is not feasible. Another answer might be to build more and larger production facilities or to spread our spend out to a hundred new suppliers or design reliable and defect-free products. I was involved with an optimization analytics study a few years ago in which the organization wanted to determine which metrics optimized profitability and EBITDA. Optimization analytics may produce a recommendation that minimizes operating costs or maximizes profitability, but keep in mind that one cannot possibly build all the factors in organizations (especially the unpredictable human factors) into these analytical exercises.

The most applicable to the organizational scans are the intelligence, descriptive, diagnostic, and discovery analytics. Predictive, prescriptive, and optimization analytics are used more in a larger specific and complex improvement project.

A word of caution is in order when designing this business analytics support process. This applies to all technology solutions like mobility, cloud computing, data warehousing, virtualization. Technology is a powerful enabler for conducting these scans efficiently, but technology can also quickly overwhelm people with information—more information than they can possibly understand, distill, and use in a true value-added way. A major consideration of technology-enabled improvement that must not be overlooked is that the real intelligence lies in the improvement practitioner and the user community in the form of human intelligence. There is no improvement intelligence software or mobile application that plans and executes adaptive systematic improvement automatically.

The process of improvement still relies on human intelligence to organize and structure the right business queries, define and scan the right baseline data, define and segment the right root cause information, analyze data with the right methodologies and tools, draw the right, data-driven conclusions, take the right fact-based actions, and close the loop with the right performance metrics.

This is often the big disconnect with business analytics activities in organizations today. If one is missing this core competency of structured and disciplined improvement, then technology is reduced to providing more information quicker—the old data rich/analysis poor syndrome. Organizations must be very wary of looking at the wrong data just because it is available, and then drawing the wrong conclusions and developing a wrong improvement strategy.

A Lean Business System is much more than an architecture; it holds a formal executive role in the organization. There is no single right way to design an organization in order to maintain a systematic process of improvement. It is always a function of the organizational business requirements and business unit structures that are currently in place, and the structure is very different in larger multinational corporations from the structure in smaller and midsized organizations.

The purpose of this section is to provide a guide for leading and organizing a systematic process of improvement. Unlike the early Six Sigma deployments most organizations do not have hundreds of people hanging around whom they can dedicate as full-time, centralized black belts. The thought for dedicated resources is there, but it is impractical and not sustainable for most organizations. We have used a different model that is shown in Figure 3.3. A Lean Business System is lead by a vice president of the XYZ Corporation business system. This role has worked well reporting directly to the CEO, or a senior operating vice president (global operations, global quality). This individual is the chair and lead facilitator of the executive core team. This is definitely a role that organizations want to keep visible in the executive suite so as to send the right message of its importance to the organization.

Figure 3.3 Organizing for Systematic Improvement

Copyright © 2015, The Center for Excellence in Operations, Inc. (CEO)

Next we suggest that an executive core team be established and tasked with the overall continuous success of the systematic process. The organization chart in Figure 3.3 is an abbreviated representation: This group is composed of a cross-functional subgroup of the executive team, business unit executives, and other influential executives. The core functions of sales and marketing, finance, operations, and engineering are represented on the team. Sometimes the CEO chooses to be an active member of the core team. The executive core team plays a key governing role in adaptive systematic improvement by:

Synchronizing and aligning the Lean Business System to the business plan and operating plan.

Synchronizing and aligning the Lean Business System to the business plan and operating plan.

Updating the CEO and executive team on progress and issues.

Updating the CEO and executive team on progress and issues.

Providing overall leadership and governance.

Providing overall leadership and governance.

Conducting, analyzing, and drawing requirements from the business scans and cultural scans.

Conducting, analyzing, and drawing requirements from the business scans and cultural scans.

Continuously maintaining the MacroCharter and MicroCharter, the living hopper of improvement activities in process, queued up, and new requirements.

Continuously maintaining the MacroCharter and MicroCharter, the living hopper of improvement activities in process, queued up, and new requirements.

Encouraging and mentoring executive and process owner engagement and objectivity.

Encouraging and mentoring executive and process owner engagement and objectivity.

Acting as the barrier resolution, resource balancer, and interference factor to keep adaptive systematic improvement on track, efficient, and continuously successful.

Acting as the barrier resolution, resource balancer, and interference factor to keep adaptive systematic improvement on track, efficient, and continuously successful.

The executive core team usually meets every week for a quick flash report of improvement initiatives and other activities in process. Its mission is to seek out the greatest improvement opportunities, engage the organization to set and hit goals quickly and efficiently, and to keep mining for the next big improvement opportunities—and most importantly, to keep adaptive systematic improvement on point. There are occasions when the executive core team has an emergency meeting for an important improvement activity, or it might dedicate a two- to four-hour working session if it is conducting a spin on the business scan and cultural scan, discuss how to accelerate improvement activities in process, or when the need arises to reprioritize and realign the contents of the MacroCharter and MicroCharter. At the conclusion of these executive core team meetings, members have action items to support the overall adaptive systematic improvement role.

In smaller and midsized, self-contained organizations (e.g., two to three sites) this organizational description provides an adequate start. However, in larger, independent multinationals, the vice president, Lean Business System, and an executive core team provides more of a policy deployment and shared services role. Larger independent business units need their own Lean Business System site leader and their own executive core team. In the Lean Business System Reference Model, the specific corporate and business unit roles and responsibilities are requirements-driven and must be architected to address particular business and cultural development needs.

One of the most important elements of a successful executive core team is to consciously disallow participant perceptions, opinions, and political issues from shaping the work of the group. Business analytics provides an objective analytics support system that is both targeted and focused on identifying the right data-driven and fact-based improvement requirements for the organization. It is the executive core team’s role to define the best and highest-impact opportunities for improvement and then to prioritize and align these activities to the business plan and annual operating plan. Members of the team should be in tune with the organization’s needs as operating executives, and they must tee up the right, fact-based improvement activities to enable high monthly performance, quarterly performance, and annual performance. This is a very important, precision-oriented role for achieving success.

Our Lean Business System Reference Model avoids the large armies of dedicated centralized black belts and other Lean resources prevalent in the past decade. The vice president of the XYZ business system needs a small centralized group of highly skilled improvement leaders and practitioners that report directly to him or her, and who focus on planning, development, providing a uniform center of excellence for talent development, maintaining overall performance of adaptive systematic improvement, recruiting special support needs such as financial analysis and validation or IT support, and assisting with special business unit improvement needs. The vice president of the XYZ business system works with each business unit general manager to plan staffing needs based on the MacroCharter and MicroCharter plans. In large organizations with large business units, it makes sense to plan on a business unit executive core team and senior improvement executive/architect and a few skilled practitioners to work with business units. This role is to develop the internal competency of adaptive systematic improvement throughout the business unit. This smaller group adapts systematic improvement and the MicroCharter even further to the specific requirements and uniqueness of a business unit. Members of this group serve as adaptive systematic improvement leaders and mentors, not doers for the business units. In smaller organizations the responsibility may reside with the business unit GM and executive team (who also serve as the executive core team) with a designated business unit lead improvement resource. This individual serves more in a project management role, organizing and prioritizing improvement needs with the executive team, providing technical mentoring and mentoring managers, teams, and individuals through the successful completion of their improvement activities. In all cases, the central XYZ business system organization works with and mentors business unit resources to develop talent through the center of excellence, and to organize and mentor business unit improvement resources through their successful activities. Another role of the business unit improvement leaders is to help business units balance the requirements of daily distractions with continuous improvement.

Overall, we have found this to be a simple and very efficient organizational approach to planning, deploying, executing, and sustaining a Lean Business System. Please keep in mind that this is one of several different options to organize adaptive systematic improvement as the organization’s business or operating system. The proper organization and infrastructure design for adaptive systematic improvement is critical to sustainable success. The actual design is driven by business requirements; present organizational structure, size, and scope; and specific adaptive systematic improvement needs. In very small, single-site organizations, for example, the best option might be to create a site executive core team and appoint a senior improvement leader. This individual is responsible for the XYZ business system and works with the executive core team and functional champions on detailed deployment planning and execution.

In every scenario there is also the option to engage proven outside experts or to proceed with an organic approach. Proven means true Lean Business System architect resource(s) that bring originality, credibility, creativity, customization, industry recognition, and a track record of successes. These professionals are much more skilled than the typical, narrowly focused “TPS preachers” of manufacturing and tools. The majority of the best Lean Business System organizations have engaged proven outside expertise to help organize and expedite the front end of their journey. This is not a statistical anomaly. While Lean Business System consulting expenses increase short-term discretionary spending, it is a great investment with a significant ROI (return on investment) when the right credible resources are engaged as executive mentors, architects, and advisors. A true Lean Business System is a legitimate core competency that organizations develop and nurture over time. It is much more than another casual replication of the TPS principles and tools. Adaptive systematic improvement is logical and looks simple, but it is not easy. The risks of failure are high when systematic improvement is not well organized and architected at the front end. The only option is to get it right!

Adaptive Leadership recognizes that behaviors influence executive choices and actions. This is Leadership 101 in theory. However, in order to evolve to an adaptive style of leadership, it helps to better understand and quantify these specific behaviors. Adaptive Leadership is supported by a conscious set of executive behaviors that can be adapted by leadership and instilled in the organization. Organizational awareness is the prerequisite for adaptivity. These behaviors are the essence of what enables adaptive systematic improvement and what creates great cultural organizations, where one continuously evolves into the other. Adaptive Leadership recognizes that organizations cannot improve how they improve or change culture by mandating the use of a set of tools or copied practices. Behavioral awareness, alignment, and reinforcement are the underpinning for creating a cultural foundation of excellence and greatness. This cultural foundation adjusts and adapts to changing business and operating conditions, always to a higher level of excellence and superior performance.

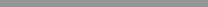

Recognizing that we are not dealing with an exact science here, we have developed a best practice leadership behaviors model, a soft control evaluation technique that is simple to use and helpful in building individual and group awareness about certain improvement-detracting behaviors. The model includes the dimensional Kata attributes of both great leadership and cultural excellence. Best practice leadership behaviors can be grouped into five major categories:

1. Vision

2. Knowledge

3. Passion

4. Discipline

5. Conscience

Within each of these categories is a set of behavioral attributes that contribute positively to adaptive systematic improvement and, in fact, personal leadership success. This is a quick and simple, attribute-based scan of leadership behaviors and is not limited to the executive suite. The CEO and his or her executive team may choose to complete the scan as a group or on each other’s styles. The scan can be used to evaluate middle managers from a 360-degree approach including their manager, direct reports, and internal customers or other individuals who interface with a particular individual. The process is consensus-based, using a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = poor, 5 = average, 10 = outstanding). We do not view the individual scores as a pass/fail competitive test, but we use them to uncover the lower score trends in an individual, a team, a functional area, another organizational segment, or a specific leadership category or its related group of attributes. Often it serves more as an awareness and self-help exercise to improve a particular leadership style or to better understand and resolve organizational conflicts. It is most useful in individual and smaller group applications; it is obvious that a full leadership behavior scan is possible on the entire organization, but it is not actionable. Another useful capability is to look at the relative difference in attribute levels over time, or before and after an educational or career development event. Table 3.1, Figure 3.4, and Figure 3.5 provide a sample from the Adaptive Leadership Assessment in the reference model.

Table 3.1 Best Practice Leadership Behaviors Scan Data

Figure 3.4 Best Practice Leadership Behaviors—Category Summary

Copyright © 2015, The Center for Excellence in Operations, Inc.

Figure 3.5 Best Practice Leadership Behaviors—Attribute Level Scan

Copyright © 2015, The Center for Excellence in Operations, Inc.

These behavior categories and their detailed attributes used in the model are contained in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Best Practice Behaviors

Most executives are extremely challenged by all the issues and information coming at them on a daily basis. This can create a lack of self-awareness of their own strengths and limitations, and can blur the strengths and limitations of their organization. These issues and challenges are complex and come in cyclic streams: many small manageable cycles for adaptive leaders and larger problematic cycles for maladaptive leaders who choose more of the same—postponement, procrastination, or complacency. It is easy for organizations to lose their way, and it is even easier for organizations to remain in denial about losing their way. Again, not a criticism: This is the reality of the warp-speed global economy where we all work.

As mentioned earlier, Adaptive Leadership is a rare commodity. Executives do not come to work one day as an Adaptive Leader and decide that their organization will become effective in an adaptive way immediately. Organizations develop the competency of Adaptive Leadership over time by responding to and resolving the challenges immediately and with the right resources and talent. It requires a major paradigm shift; a personal realization that you don’t know what you don’t know; a recognition of serious organizational voids; a painful cycle of reckoning, renewal, and enlightenment. The ideal situation is to transform every internal executive, leader, manager, and process owner, but it is neither realistic nor timely. This leadership mindset adjustment is not always effective with internal resources that are profoundly accustomed to their various “as-is” and firefighting routines. The most successful organizations embrace talent acquisition—injections of new external talent to make the necessary organizational competency improvements.

Intervention plays a large role in Adaptive Leadership. This is not a negative activity but a very healthy organizational development process. Most organizations proactively reinforce cultural expectations and the accepted code of conduct. However, there are a number of reasons why executives, managers, and associates temporarily abandon these values. Many of these reasons are directly attributable to leadership behaviors, choices, and actions. Over time, these diversions become accepted because nothing is done about them. One of my favorite examples is embedded in this executive comment: “We do Lean Monday through Thursday, and Friday is rework and repair day.”

Leadership must play a strong intervention role in order to keep adaptive systematic improvement on track; we are not insinuating a “Gestapo” role here. We are talking about systematic interventions in which leaders view these diversions in terms of the whole system rather than reprimanding individuals for doing what they thought they were supposed to do. Leadership’s role in adaptive systematic improvement is to set up and maintain a positive environment for success, to create the right improvement Kata. Leaders and managers must learn to act as counselor, mentor, personal coach, technical advisor, coordinator, educator, and barrier and deadlock buster. They must learn to ask the right questions and get their people to think rather than giving answers or direct orders. They must practice the conscious habit of continuous power hits to their organizations. Power hits are the quick, informal, conscious 15-second messages that demonstrate commitment, interest, and expectations.

A final thought about interventions. Most executives like to approach this topic in a positive light. Creating a talented, empowered, and happy workforce is the goal and the right thing to do. In the real world, interventions are not always a bed of roses. Occasionally I have worked in organizations where there are a few real improvement troublemakers. Often these people can be turned around with the right attention and guidance. However, when organizations allow one of these characters to undermine all the great work of groups of dedicated people, it is very destructive on any improvement activity. Furthermore, it sends a very negative message that improvement does not matter; improvement is not on the radar screen. Intervention is also about having the leadership fortitude to remove the detractors and obstacles from adaptive systematic improvement.

Nobody said that Adaptive Leadership (or leadership in general) was easy. A Lean Business System forces executives to step out of a role of moderating the happenings in their organizations, to proactively pushing the limits of what their organizations can achieve. It is a mindset change away from how well are we doing to how great can we become? Here are a few tough questions that executives should ask themselves about their organizations:

When was the last time you stood back and rated your performance and that of your management team? Is there a shared notion of what, why, where, when, how, and who need to change?

When was the last time you stood back and rated your performance and that of your management team? Is there a shared notion of what, why, where, when, how, and who need to change?

Are you and your team best suited to running your organization in its current stage of operating challenges and growth? Where are the voids in strategy and execution of the desired changes?

Are you and your team best suited to running your organization in its current stage of operating challenges and growth? Where are the voids in strategy and execution of the desired changes?

Who are the leaders and champions of innovation, improvement, business transformation, and change management? Who are the maintainers and sustainers of the status quo? What and who are the barriers to change?

Who are the leaders and champions of innovation, improvement, business transformation, and change management? Who are the maintainers and sustainers of the status quo? What and who are the barriers to change?

How are you doing on your organic Lean, Six Sigma, and other strategic and/or continuous improvement initiatives? What is the ROI and validated value contribution to the business? When do you expect to reach the industry benchmark annual savings run rate of 3–10 percent+ of revenues?

How are you doing on your organic Lean, Six Sigma, and other strategic and/or continuous improvement initiatives? What is the ROI and validated value contribution to the business? When do you expect to reach the industry benchmark annual savings run rate of 3–10 percent+ of revenues?

What specific strategic transactional initiatives are in place to flush out the hidden waste in knowledge processes such as new product development, supply chain management, R&D and innovation, excess/obsolete inventory, returns and allowances, warranty and repairs, cash to cash, product portfolio management, marketing and promotions, advertising, sales and channel management, sustaining engineering, quality management, IT, sourcing and procurement, and so on? What has changed, and how has it impacted operating performance?

What specific strategic transactional initiatives are in place to flush out the hidden waste in knowledge processes such as new product development, supply chain management, R&D and innovation, excess/obsolete inventory, returns and allowances, warranty and repairs, cash to cash, product portfolio management, marketing and promotions, advertising, sales and channel management, sustaining engineering, quality management, IT, sourcing and procurement, and so on? What has changed, and how has it impacted operating performance?

Do you have a chance of becoming a best-in-class industry performer within the next 12–18 months with the current leadership, strategy, and organization?

Do you have a chance of becoming a best-in-class industry performer within the next 12–18 months with the current leadership, strategy, and organization?

Organizations develop an Adaptive Leadership competency when they are able to respond to and resolve challenges in real time, with their existing (and acquired) resources and talent capabilities. This anemic economy has swung the needle toward organic improvement with traditional Lean methods in the interest of cost containment, but it is not working out for many organizations. Additionally, organizations have a natural tendency to settle into a comfortable operating mode and delay true, proactive, and adaptive systematic improvement. Adaptive Leadership thinking breaks this traditional cycle and renews the opportunities for improvement in a very precise and systematic way.

At the manager, first-line supervisor, or team leader levels, the form of Adaptive Leadership becomes more of a proactive execution role. Associates need a structured routine and pattern of thinking about process improvement. Toyota uses an approach called the five questions which is deeply embedded in how their people think and work. Organizations need to create this competency with executives, managers, and associates. Since 2004 we have used a simplified define-measure-analyze-improve-control (DMAIC) pocket template from our basic improvement skills (BIS) education for associates and individual contributors. It serves the same purpose as Toyota’s five questions while providing a consistent way of thinking about adaptive systematic improvement throughout the organization. We have kept the DMAIC structure in our Lean Business System Reference Model because it provides an effective, common universal language of improvement. We have also adapted other open methodologies for nonlinear improvement situations.

The following list shows the systematized set of DMAIC questions from our BIS Pocket Guide that managers, supervisors, and team leaders should be instilling in their people as a daily way of thinking:

Define:

What is the challenge or detractor?

What is the challenge or detractor?

What is the improvement goal and objective?

What is the improvement goal and objective?

What are the general benefits?

What are the general benefits?

What is the next step?

What is the next step?

Measure:

What is the baseline performance?

What is the baseline performance?

Is the problem confirmed with data?

Is the problem confirmed with data?

What are the financial benefits?

What are the financial benefits?

Analyze:

What are the root causes of the problem?

What are the root causes of the problem?

What are the options for improvement?

What are the options for improvement?

When can improvement be implemented?

When can improvement be implemented?

Improve:

What is the best improvement option?

What is the best improvement option?

What are the barriers, dependencies, and contingencies?

What are the barriers, dependencies, and contingencies?

How will you measure and confirm success?

How will you measure and confirm success?

Control:

Did the actions solve the problem?

Did the actions solve the problem?

How will you sustain improvement?

How will you sustain improvement?

Are there any other actions needed?

Are there any other actions needed?

What have you learned from this activity?

What have you learned from this activity?

Copyright © 2004, The Center for Excellence in Operations, Inc.

Today there exists more waste in many organizations than when they first embarked on their Lean journey years previously. It is nobody’s fault: The sheer velocity, complexity, and competitive nature of change is moving at a faster rate than the organization’s maintainer and sustainer leaders can deal with. Waste is an organic phenomenon in organizations that grows without deliberate attention and proactive countermeasures. Regardless of the economic dominos, Adaptive Leadership and best-in-class performance still remain an executive choice.

In this economy, human capital is the most valuable asset in organizations. It all comes down to having the right talent in the right places at the right time. Given that many “A” players move on and that there will be mismatches in leadership styles versus business cycle needs, the process of talent planning, development, retention, rationalization, and acquisition is critical. Chaos and constant change, increased complexity, and “improving how we improve” are givens in this new economy. This notion of improving how we improve can be accomplished only with the right improvement Kata. Adaptive leaders create adaptive organizations that are capable of morphing themselves into different structural and customer- and market-focused value stream organizations on demand. Best performing organizations are led by adaptive leaders that recognize and act immediately upon the need to change, including bringing in new talent from outside the organization.

Burton, T. 1995. The Future Focused Organization. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

Cockerell, L. 2006. Disney Great Leader Strategies. Disney Institute, Orlando, Florida.

Collins, J. 2011. Great by Choice. Harper-Collins, New York.

Iacocca, L. 2008. Where Have All the Leaders Gone. Scribner, New York.

Liker, J., and Convis, G. 2012. The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership. McGraw-Hill, New York.

MacKey, J., and Sisodia, R. 2013. Conscious Capitalism: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts.