This chapter provides guidance on how to adapt the reference model architecture, subprocesses, and other related critical success factors to an organization’s operating environment. It is not possible to explain all the details of a complete build-out of a true Lean Business System. Remember that this effort is an evolutionary process and that the Lean Business System Reference Model™ is a guide or road map for the journey. We share some of the organization-centric retrofitting insights and best practices that are outside of the Toyota Production System (TPS) and that have been executed with great success. As a consultant I am blessed to be exposed to so many global learning opportunities. I have spent hundreds of weekends where our clients are located to observe and talk to people about culture and to learn more about culture and local customs. I also enjoy trying local cuisines and making the effort to adapt to local customs; it comes with the territory of 100 percent travel, and clients appreciate your interest in their language and way of life. All these experiences make one realize the importance of culture when introducing change.

Now a little fun: Think of the past and present state of Lean as a group of friends in the backyard grilling burgers. All those involved, including the grill masters, are limited to the recipe. Maybe they can add spices or sauces or cheeses, but the small group of people is content with burgers. Now elevate one’s thinking to feeding a large, diverse group of people from 20 countries. The grill and burgers are irrelevant to the vegetarians, people who eat only fish, and others who have different dietary needs and expectations. The reference model is analogous to turning the burger grill masters into five-star Michelin master chefs who are skilled with a variety of kitchen equipment, utensils, and ingredients and are capable of quickly adapting and preparing a creative and delicious plate on demand for any appetite around the globe. The greatest difference between the two scenarios lies in the skills, knowledge, talent, creative and innovative thinking, no-fear attitude, and behaviors of doing whatever it takes in any situation to achieve success. This is the difference between a Lean manufacturing system and an enterprisewide Lean business system.

The Lean Business System Reference Model is just that—a reference model, with many proven real-world insights and best practices to create an organization-centric Lean Business System. The reference model is a pragmatic and useful guide that is always in a work-in-progress state and continuously under development. After interviewing a large cross-section of individuals and completing the Operations Excellence Due Diligence™, executives and practitioners are equipped with the business requirements, vital signs, cultural climate, and other related information necessary to adapt and architect their own enterprisewide Lean Business System. Some of what we discuss in this book is directly applicable; some features and functionality will require deeper thinking and design. Following the reference model enables organizations to define the requirements of their own Lean Business System and its subprocesses.

A word of caution is in order. Organizations are always overanxious to implement what they believe to be the next magic mantra of improvement. Like the Toyota Production System, it seems quick and easy to follow a hasty knockoff strategy, but organizations overlook the most important (invisible) behavioral and cultural development needs. A Lean Business System is not the next magic mantra or silver bullet, but the architecture, design, implementation, and sustainability are new to most organizations. A true Lean Business System is a never-ending journey to excellence and superior performance. Organizations have copied the visible principles and tools, but they must define and evolve their own mojo of improvement—their own Kata. This is a long and deliberate process of Adaptive Leadership, continuity of purpose, and a passion for human capital development. The reference model provides the means that will enable you to think through the requirements and challenges for success. It provides a framework for enterprisewide improvement and cultural excellence—and there are no shortcuts. Organizations must invest more time in the “invisible” Kata side of the house (behavioral and cultural development) to become great at adaptive systematic improvement with continuous “visible” benefits. Do not mimic or attempt to copy and paste the surface reference model, or the journey will be cut short very quickly. All industries have the capacity to improve beyond what is thought to be impossible or unreachable when they lead and engage the full potential of their organizations. People get organizations there, not tools.

A Lean Business System must be adapted to a specific industry and its unique operating characteristics. For example, a Lean Business System will operate differently in a consumer goods, automotive, pharmaceutical, or aerospace and defense industry because of different market dynamics, customer expectations, operations (repetitive, job shop, process, and supply chain designs), performance criteria, and compliance and regulatory requirements. There is an even greater difference between manufacturing organizations and retail/wholesale distribution, healthcare, and financial service organizations. In the transactional process space, there tends to be more similarities than differences between organizations. My personal experiences with over 300 different clients globally is that the same holds true for Lean and continuous improvement in general. Exposure to this many organizations enables one to think of, and adapt possibilities that a practitioner with experience with only one or two organizations in the same industry may never think about. The important point is that the architecture of a Lean Business System integrates all the business requirements and cultural characteristics. In effect, the architecture addresses the, “Our business is different,” or “We can’t do this because,” or, “We’re regulated by law,” or, “We don’t assemble cars; we save lives” issues in organizations all of which build the perception is reality walls and have proven to be very real showstoppers of Lean and continuous improvement in the past. Adapting the architecture of a Lean Business System to specific industry requirements increases the rate of acceptance because it clarifies the objectives and what-why-when-where-who-how questions within a specific environment.

One area that could benefit from adaptive systematic improvement is Lean healthcare. Many practitioners have directly ported over the principles and tools of the Toyota Production System without giving deep thought to the significant differences in industry structures. For the industry as a whole it has been a Lean false start. A dozen or two hospitals really get it and have achieved significant benefits with their Lean initiatives. Many hospitals have not committed to Lean and continuous improvement for the long term because of their long cultural standard of external agency reimbursements to cover costs. Many practitioners have also been unsuccessful at taking advantage of the best opportunities for improvement in hospitals. As the population ages and other industry changes evolve, the game has changed drastically—with reimbursements shrinking while costs continue to increase at double-digit rates. Many hospitals are waiting for new legislation or filing lawsuits with their states to resolve their shrinking reimbursement dilemma. This is not adaptive systematic improvement with structured means and deliberate actions.

The administrative areas of hospitals have similarities in terms of transactional process improvement. However, the rest of a hospital environment is very different from an assembly line. Lean has not been explained and adapted properly as a way to help the clinical, laboratory, and primary care staff to make their lives easier. Additionally, Lean has missed the mark in terms of eliminating waste in the highest-impact areas of a hospital, namely the highest revenue-producing centers and highest cost drivers such as facility and operating expenses. Lean has been implemented in the visual lower-impact areas with the same focus on ported-over manufacturing principles and tools, while the strong clinically driven Kata has remained the same. I visited a large hospital as a patient recently and found myself in a nice conversation with a nurse about the hospital’s Lean program. She said, “It started off with a lot of interest, lasted about six months, and we’re finished with it now.” I probed about some of the activities she was involved in, and she replied, “Mostly cleaning up and labeling supply rooms and medicine cabinets, mapping our processes, and stuff like that. Most of it is gone now; we’re back to normal.”

The largest opportunities in hospitals require a combination of transactional process improvement plus technology (i.e., real-time scheduling and logistics, real-time tracking with tighter quality controls on services and medications, digitally distributed full patient dashboards, etc.). These resources within these areas must become heavily committed and engaged, and they must also understand that Lean is about removing their barriers to success. For example, many operating rooms and equipment labs are severely underutilized from a private industry perspective (like 10–30 percent). Supply chains are fragmented and create tremendous waste in different equipment, supplies, and maintenance contracts. It’s just the institutionalized way that things have always worked in hospitals. We mentioned earlier that a small group of hospitals has achieved great success with Lean, but these institutions are the exceptions. Major innovations in scheduling and quick changeover thinking could increase the utilization rates and revenue-producing opportunities of expensive MRI equipment and operating rooms. This does not suggest that doctors and clinicians must work faster; it means finding a way to accommodate one to three additional operations per day or three to four patient appointments on key revenue-producing equipment by eliminating waste in the system. There are plenty of idle time and resources to implement these improvements, one additional surgery per day or an MRI or X-ray lab working at just 50 percent of capacity would make a tremendous difference. Consolidating spending through a single supply chain would also reduce significant waste. Again this requires engagement of the clinical and laboratory staff, and the incentive is their compensation. It also requires a new Kata that time is money, but not at the expense of the patient experience. These improvements can represent millions of dollars in incremental revenue for a single hospital.

As practitioners have found in manufacturing, reducing time and waste also improves quality at the same time. Lean practitioners have a moral obligation to win over physicians and other clinician and lab resources, help control double-digit cost increases, and find ways to offset reductions in revenue reimbursements. Labeling rituals and setting up a pull system for Jell-o and coffee creamer just aren’t making a difference. The opportunities for improvement are enormous, but it requires a trip back to the drawing board and thinking about how to engage (rather than alienate) the right people. The hospital of the future will probably resemble a FedEx or Amazon, capable of moving people through a distributed network of service centers (maybe with no waiting rooms as inefficiency buffers) with even higher levels of quality and patient care, a much shorter length of stay, and a more positive total patient experience—and hopefully much more affordable.

At a specifics level, every organization has different strategic and operating challenges, planning systems, enterprise architectures, organizational structures, process inefficiencies and wastes, leadership challenges, levels and mix of talent development, and behavioral and cultural development needs. The purpose of the Operations Excellence Due Diligence in the reference model is to help organizations define and adapt their business requirements and cultural development needs to their Lean Business System. By now, it should be obvious that a tools-focused Lean manufacturing approach is not robust enough to significantly and positively influence these areas at an enterprisewide scale. Many of these tools-based initiatives have generated transparent improvements that do not impact customers or the organization’s strategic and operating performance. Creating the capability of living, laser-targeted planning and deployment ensures continuous alignment between an organization’s holistic improvement needs and what people are doing on a daily basis to fulfill these needs.

Cultural development needs are the great missing link in Lean and continuous improvement initiatives, particularly in Western organizations. The living laser-targeted planning and deployment process and the balanced scorecard are two useful references for identifying gaps in this area. It takes structured means and deliberate actions to keep a Lean Business System aligned with behavioral and cultural development needs. Adaptive Leadership is a given to create the right environment, communicate expectations, reinforce behaviors and guiding principles, remove the barriers to success, and build a seamless teaming organization. The best approach is through the rigorous and widespread practice of coaching, mentoring, doing, and continuous learning. This is not an ad hoc practice that happens on its own. We use the deliberate word again because it requires the formal cycle of defining cultural weaknesses and needs, developing a plan to grow patterns of behavior and cultural attributes to higher standards of excellence, executing with the right actions and efforts, and measuring progress. In effect it is a complex PDCA for improving invisible behaviors, routines, and cultural attributes. There is so much unleashed power to improve by creating the right Kata and cultural standards of excellence. There is a saying, “Let the cat out of the bag,” a colloquialism meaning to reveal facts previously hidden. Organizations are just beginning to appreciate and accept this tremendous under the radar capability in the Toyota Production System. Now it is time for all organizations globally to “let their own Kata out of the bag.” The future of Lean is an enterprisewide business system, an adaptive systematic process of improvement that is highly leveraged by the skills, knowledge, talent, and full potential of people in organizations. This has been a superficial topic of discussion for decades; the secret is doing it for real—putting the tools aside and developing people—and evolving the right patterns of behavior and cultural attributes that exist at Toyota and within several other great organizations. Leadership cannot delegate behavioral and cultural development to internal change agents or the human resources department. Eventually these efforts become thorns in the side of change management. As we always say, “The soft stuff is the tough stuff,” but also the greatest stuff for continuous improvement and superior operating performance.

The cloud, big data, mobility, additive manufacturing, business analytics, virtualization, advanced robotics, artificial intelligence, neuromorphic technologies, and distributed manufacturing models have arrived. Drone logistics and doorstep delivery is not far behind. In the future more organizations will resemble the business models of Amazon and Google that provide almost every product to the marketplace within 1–3 days. These organizations are the cybermalls of the future. The combined technologies enable these and many other big box organizations to work as a large transparent manufacturer and distributor of everything, contracting with a large network of suppliers and taking advantage of drop shipments and other logistics strategies as close to the customer as possible. Another growing trend is a rise of private labeling, custom bundling and packaging, and other specialty requirements by large technology-enabled organizations which add cost and cut into the margins of retailers and their supply base. Organizations need a higher order paradigm of Lean to address these complex emerging technology-enabled innovations in business models.

The best time to make decisions about how to integrate improvement and technology is when an organization designs its Lean Business System architecture. A best practice in the reference model is to map the architecture and subprocesses and then think about the technology requirements to further enable the system’s efficiency and effectiveness. This is a good time to recruit an IT resource that can create a parallel technology road map to support a Lean Business System. This includes the identification of system requirements from an IT perspective and then identifying and recommending alternative technologies such as business analytics, cloud and mobility applications, digital performance dashboards, virtualization technologies, and other emerging technological solutions. The objective is not to turn this into a two-year IT development project but to efficiently phase in the right technology solutions with the right priorities and the highest payoffs.

Another need in this area is that Lean practitioners become more familiar with technology options. Relying solely on an IT resource is not recommended. Executives, IT resources, and Lean practitioners must all work together to find workable technology solutions that enable a Lean Business System’s ultimate success. In a Lean Business System, people enabled with technology are much more important than the standard collection of improvement tools.

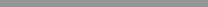

Local cultural norms must be considered when implementing a Lean Business System. Choosing to downplay the cross-cultural encounters in a global Lean Business System sets up major barriers to success. There are major cultural differences, for example, among behaviors in the United States and Europe and South America and the Far East. On a microlevel, there are even subtle cultural differences between people and organizations in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Hackettstown, New Jersey; Columbus, Ohio; St. Louis, Missouri; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Cupertino, California; Houston, Texas; Atlanta, Georgia; Knoxville, Tennessee; Germantown, Maryland; and Melville, New York. Culture is the foundation of adaptive systematic improvement; failure to recognize and integrate local behavioral patterns of work and culture is likely to take down the house of a Lean Business System. For large multinationals, a global Lean Business System requires a deep understanding of the cultural ramifications of introducing an enterprisewide systematic process of improvement. Culture change is an evolutionary journey that strongly influences behaviors, trust, collaboration, and cooperation as well as the Kata elements of a Lean Business System. Organizations cannot simply transplant the cultural standards intact from one country to another and expect success. Executives must begin with their local behavioral and cultural realities and build continuity of purpose and trust before they begin changing patterns of behaviors and building a renewed culture of excellence. Practitioners with global implementation responsibilities must also appreciate and play by the local cultural norms. Some of the global cultural idiosyncrasies of the reference model are provided in Table 9.1, Select Global Cultures. These cultural references must be part of the Lean Business System design in a particular geographical location. Table 9.1 provides a starting point for appreciating and understanding the different but okay attributes of culture around the world. This is a simple guide for thinking through the various elements of the reference model and how best to architect and implement each element with local culture in mind.

Table 9.1 Select Global Cultures

In the Lean Business System Reference Model, the purpose and objectives of the architecture are almost universal because the continuing need for improvement is universal. In fact, the architecture and its subprocess structure are universal in concept. It is the what-where-when-why-who-how questions that introduce differences in leadership, planning, communication, execution, and sustaining a culturally centered Lean Business System. Some of the answers to these questions may also be universal, such as people engagement, talent development, and strong coaching and mentoring, although there might be small idiosyncrasies in daily practice. The largest challenge of implementation lies in finding the delicate balance between the standard architecture and the how of implementation across different cultural environments. A quick study of Table 9.1 will stimulate thinking about how to better adapt systematic improvement in various parts of the globe. Implementing a Lean Business System in Germany, the United Kingdom, Spain, China, or Peoria, Illinois, requires different behavioral and cultural considerations in the architecture. These considerations are also important in cross-collaboration efforts around the globe. This requires an appreciation for local cultural attributes and accepted codes of conduct in different cultures around the globe. This appreciation goes beyond a Lean Business System. When someone from a large multinational corporation looks at Table 9.1 in greater detail, for example, it is not surprising to learn why there are global supply chain or global software development complexity issues. Whether it is an issue of religion, gender roles, dress standards, diet, or any other dimension, it is important to always realize that culture is deep seated in every person’s sense of self. Passing judgment is destructive and builds barriers to change; understanding other cultures as different and okay rather than better or worse opens new global opportunities for breakthrough improvement.

There is a plus side to the complexities of different cultures. My prediction is that two common threads will significantly influence the polarization of Lean and culture change: people and technology. Actually it is 50 percent observation and 50 percent prediction. Today it is a common daily practice for people to regularly collaborate with different people in different time zones and geographical areas. Cross-cultural collaboration and innovation work environments can help build trust—the currency of collaboration—among coworkers, between employees and managers, and between customers, suppliers, and other stakeholders. Establishing trust is the foundation of Kata and can be accomplished by studying the local cultural traits that outwardly manifest themselves in the workplace.

Technology is homogenizing many elements of culture through virtual mobile and video-based collaboration, teaming, coaching, and cross-cultural learning. Twenty years from now it is predicted that 50 percent of the workforce will be operating in a virtual mode. Think about the impact on Lean. IBM, SAP, and a few other organizations are there now. Twenty years ago, thousands of employees came to work at IBM’s headquarters; today on any given day, it is a ghost town, but the employees are accessible through technology. People are working from a customer’s site, their homes, automobiles, Starbucks, or a son’s soccer game. People are also connected to work much longer than they were 20 years ago. Working two days a week from home is rapidly becoming the new norm.

All gains have some trade-offs. For example, technology is creating the loss of interpersonal and social content at the office. This is too important to be just another trade-off. There is extensive research being conducted at MIT on advanced cybertechnology to improve these interpersonal and social losses resulting from technology. IBM and MIT have been developing simulated cyberconference capabilities in which participants can digitally regain the human interaction element of communication. It is a cybergemba environment. Developers are forecasting the future and discussing the ability to meet and collaborate with associates and translate different languages in real time. Early signs of this evolving capability demonstrate that people will be able to meet face to face in cyberspace regardless of geography, language, and other constraints. Imagine six people in a cybermeeting, all talking in their native language; everyone can interact with each other, share exhibits and other documents, and fully understand the conversation. This continued evolution of technology changes not only the way people work but also the way people live. However, it will never homogenize global culture into a single universal model. Despite the advances in technology, understanding different cultures is critical for architecting a Lean Business System and larger global success.

The Lean Business System Reference Model promotes the importance of developing the right behavioral patterns and cultural attributes as well as appreciating cross-cultural differences in designing an organization-centric Lean Business System. As the heading states, culture matters; it is the foundation and ongoing underpinnings of a Lean Business System. Executives and Lean Business System practitioners cannot overlook the fact that culture is the organization’s civilization and social control system. This is a universal principle in all organizations and in all cultures. Within an organization, Kata is not possible unless executives and managers deliberately promote and reinforce the right thinking and behaviors—and sanction the wrong thinking and behaviors. They must also engage, empower, and develop their people to be a primary part of the solution. The goal is to create norms of behavioral patterns through coaching, collaboration, learning and development, or consequences if necessary. As culture evolves to a higher state, it becomes a business immune system, preventing waste and inefficient practices from creeping in and taking hold of progress.

What works well within one organization is not a universal solution. This is the purpose of providing Table 9.1 as a starting point. “We’re all different,” and this is fine as long as it is recognized and built into a Lean Business System. Organizations cannot impose their culture on others just as organizations cannot directly copy and paste the culture of other organizations. Toyota’s culture incorporates all the principles and behavioral ingredients needed for successful continuous improvement. No one could argue about these principles and behavioral ingredients, but the real challenge is adapting them to a culturally acceptable approach. The only option for success is to evolve an organization’s own local culture and characteristics to a higher state of excellence.

A universal principle about culture is that people become outstanding contributors when they are engaged, empowered correctly, and encouraged to participate in open dialogue without fear. They also improve with planned and deliberate behavioral and talent development. I lost count a long time ago of the clever ideas that cell operators, stockroom clerks, machine shop workers, maintenance mechanics, quality control technicians, welders, electricians, buyers, planners, customer service representatives, material sweepers, and others have come up with to save the day. It’s not just a Toyota thing; all organizations have the opportunity to engage their people and benefit significantly from the results.

Complex transactional processing environments have introduced new challenges for the improvement practitioner. Many Lean initiatives have missed the mark in these areas because of limited thinking concerning the principles and tools of the Toyota Production System. Once again, this is not a criticism; improving new product innovation or global supplier management or advertising effectiveness requires a much more robust level of problem solving. On several occasions we have found ourselves in severe turnaround circumstances where leadership needed to correct situations now and could not wait for the usual analytical and graphical approaches. In other complex situations we have found ourselves and our client resources totally overwhelmed, trying to pinpoint the right root causes and develop the right corrective actions. Nothing in the standard toolbox of Lean, Six Sigma, theory of constraints, and other methodologies filled the bill. This is a time to remember that even Frederick Taylor did not start out with a list of defined principles and standard improvement tools; he was clever enough to develop them along the way for particular improvement scenarios.

These are situations in which it is best to put all the tools aside and freelance map the problem situation and its cause-and-effect relationships. Lean practitioners worth their salt should be creative enough to engineer themselves and a team through a complex challenge. Many of these types of challenges have reflexivity—circular relationships, interaction properties, and interconnectivity between causes and effects. In essence, causes and effects are multidirectional and influence each another, so neither can be easily assigned as causes or effects. Furthermore, causes and effects are relative at any moment. These situations require deeper and broader skills and a designed experimental analytics approach (not design of experiments or DOE). Basically this involves designing and adapting a nonstandard analytical problem-solving methodology for this unique situation. Throwing the standard TPS tools at these complex situations creates nothing but an improvement ricochet effect. The following material provides several examples from the reference model.

Abstraction factor analysis is a fact-based approach to understanding and evaluating the utilization of shared resources on new product development projects. The abstraction factor itself is a measurement of the number of steps a resource is away from the executive development program manager responsible for the successful completion of a project. An abstraction factor of 1 represents a team resource that is a direct report; an abstraction factor of 9 represents a team resource that is several functions, business units, and site locations away from the executive development program manager. The higher the abstraction factor, the more likely a resource will receive invisible direction(s) and shifts in priorities from others in the abstraction chain. In other words, the many managers and supervisors closest to their resources involved in cross-functional teams can inadvertently throw large development efforts off course by interjecting with a pressing immediate need in their own areas. This is not limited to new product development; this invisible disruption occurs in all transactional processes in many organizations in multiple sites, and/or people involved in teaming efforts.

Now we discuss how to conduct the analysis. To initialize the analysis, templates for the portfolio of gate-approved projects are created with a list of team members and the resources involved in each project. In effect, a matrix for each live project with its organizational mapping origins resembles the matrix set shown in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Abstraction Factor Analysis Matrices

Copyright © 2015, The Center for Excellence in Operations, Inc.

Next each project matrix is compared to the organization chart and an abstraction factor is calculated for each person for each project. Each template includes other critical project data (stage/gate status, budget, actual time reported by individual by project, development complexity, etc.) in the abstraction factor baseline matrix. Now there is a baseline of quantifiable data that enables the evaluation of project status and resource utilization, and the calculation of the costs and lost opportunities associated with disruptions to the development process. These costs and lost opportunities do not exist on the financial statements because they are “hidden.” This analysis provides the ability to see the unknown and draw valuable conclusions when correlating abstraction factors and actual versus planned resource utilization with project status and potential lost revenue.

The analysis is not complete yet. It still requires further investigation to quantify the “why-why-why” around these issues. Abstraction factor analysis plus the development time reporting system provide the ability to drill down to specific projects and individuals and measure actual versus planned allocated time spent on projects or if the best resources are assigned to the highest-risk programs. The big difference is that people are sitting in meetings armed with hard, Minitab-generated analytics and facts and not wasting time with attribute-based explanations. Using this approach, it is not unusual to find that actual development time spent might be as much as 30 percent or more below planned development time at any given point, meaning that resources are pulled away from what they are scheduled to be working on. The opposite may be true where a project is resource overloaded at the expense of all other projects in the portfolio. Another common occurrence is a single resource being so overloaded that the associates working on the project cannot possibly get anything completed effectively and on time. These people are creative enough to find shortcuts and work-arounds to meet deadlines, but there are more serious consequences further downstream in the development process. All these situations create significant project delays, design process and quality issues, budget overruns, and late time to market.

The first step of the analysis is to design a sampling plan, a matrix of data elements that will help to describe and solve our problem. Abstraction factor analysis is a type of transaction stream mapping. Sample data are collected every time a process breakdown or disruption to a project schedule is detected. This sampling process is not a witch hunt; rather it is an objective effort to understand the organizational dynamics at play behind the formal system. Sample points are based on individual activities skipped, incomplete, incorrect, or late in each development project and are identified during and in between the weekly program manager’s review meetings. For each incident, the following six questions need to be answered to better understand the individual disruption sample points:

Who caused the disruption (name and reason) and on what project?

Who caused the disruption (name and reason) and on what project?

What caused the disruption to happen?

What caused the disruption to happen?

Where in the organizational network did the disruption occur (individual, manager, organization)?

Where in the organizational network did the disruption occur (individual, manager, organization)?

When did the disruption occur?

When did the disruption occur?

Why did the disruption happen, and what was the real root cause of the disruption?

Why did the disruption happen, and what was the real root cause of the disruption?

How could this disruption have been prevented?

How could this disruption have been prevented?

Since samples are collected across all gate-approved projects over time, they are a good indicator of how the overall development process is working. Using simple Pareto analysis, scatter plots, regression analysis, and other simple graphical and tabular analytics, abstraction factor analysis quantifies the surface-level hidden waste in the development process resulting from shared resource issues such as:

Projects that are the furthest behind schedule that are causing the highest lost revenue potential because they have high complexity and high abstraction factors.

Projects that are the furthest behind schedule that are causing the highest lost revenue potential because they have high complexity and high abstraction factors.

Data patterns that provide a quantitative means to identify the resources and the management chains causing the most disruptions to projects (e.g., resources with highest recurring abstraction factors, common managers in the disruption chains, workload impact on abstraction factors, etc.).

Data patterns that provide a quantitative means to identify the resources and the management chains causing the most disruptions to projects (e.g., resources with highest recurring abstraction factors, common managers in the disruption chains, workload impact on abstraction factors, etc.).

Resources working less than the planned allocated time on development projects because they are being directed to work on other things by other executives and managers in the abstraction factor chain.

Resources working less than the planned allocated time on development projects because they are being directed to work on other things by other executives and managers in the abstraction factor chain.

An assessment of the best resources with the right skills who are often not aligned with the specific needs of projects. The best resources are also spread so thin across multiple activities that they cannot be effective at any single effort.

An assessment of the best resources with the right skills who are often not aligned with the specific needs of projects. The best resources are also spread so thin across multiple activities that they cannot be effective at any single effort.

Resources working hard but not together. The harder people work, the more they fall behind because they are working and competing against each other’s resources, not in a synchronous program flow mode based on the facts.

Resources working hard but not together. The harder people work, the more they fall behind because they are working and competing against each other’s resources, not in a synchronous program flow mode based on the facts.

The actual and projected compression times for the latter phases of development which set off more shortcuts and work-arounds, and certain quality, reliability, and performance problems after final release to market.

The actual and projected compression times for the latter phases of development which set off more shortcuts and work-arounds, and certain quality, reliability, and performance problems after final release to market.

Abstraction factor analysis enables program managers to collaborate and smooth out project flows, and prevent much larger problems from occurring downstream in the development process. Abstraction factor analysis also provides a residual input into future resource planning and talent development. By the way, these typical findings are not a slam at executives, program managers, and resources who are usually working 120 percent to bring projects to market. Programs are never late because people are not working hard or because they are intentionally inefficient. It is a limitation of the development process and our inability to clearly see and identify the root causes of problems with our normal senses and traditional approaches to improvement. This discussion has focused on new product development, but the analysis is applicable to any complex transactional process (i.e., global supply chain, software development, packaging design, etc.) with many shared resources, touch points, and multiple organizational involvement.

Value stream mapping (VSM) has produced mixed value in organizations, and in some it has become a “VSM gone wild” exercise. The traditional Lean textbook VSM approach tends to be more about producing a large diagram of the entire process and then attempting to improve the whole. In far too many cases it becomes a world hunger exercise in practice, particularly in the professional, knowledge-based transactional process space. It uses a static snapshot of descriptive data and includes very little analytics to pinpoint major detractor root causes. It also does not enable people and teams to really understand the various analytical input/output variables and their relative influence on longer-term process performance. It pushes people to chase symptomatic problems rather than true root causes of performance. And, because it deals with a static picture of the process at a single point in time and space, it has a short “shelf life” of usefulness. A VSM that takes six months to create is about as useful as a single six-month summary of delivery performance—nice to know, but nonactionable.

One example that comes to mind is an organization that hired a Lean consultant to help with VSM. The consultant led an internal team through a year-long exercise, and the only thing the organization had to show for its efforts is walls covered with massive VSMs that were incorrect, incomplete, or had changed since the original work. I visited this organization where the team leader began explaining the VSM while she described all of the nonstandardized practices, procedures, and workarounds not shown on the map. As we talked further she was removing, writing on, and repositioning sticky notes and saying, “This doesn’t really work like that,” and “These data are incorrect.” Then she showed me the team’s improvement punch list which included purchasing more printers and fax machines, turning up the office heat, eliminating the distribution of a few document copies, buying more comfortable chairs, better communication, more raises, flexible work hours, new report requests from IT, and many other changes unrelated to the massive processes hanging on the walls.

During another meeting team members made comments like, “Management will not let us stop this effort,” or, “It is a complete waste of time,” or, “We followed our consultant’s advice right over the cliff—even he doesn’t know what we should do next.” How do you think the Lean Kata has been influenced in this organization? The typical VSM process is primarily attribute- and snapshot-based and consumes months of time, resources, and money. By the time people realize the limited use of this approach, the organization cannot reverse the cost of its huge waste exercise. This does not happen 100 percent of the time, and several organizations have generated impressive successes from the correct application of VSM. However, the wallpaper syndrome happens in far too many instances, and a better way is needed in this fast and furious economy—to improve the speed and value from value stream mapping.

We have learned through hundreds of client experiences that value stream mapping works best as a living diagnostic and corrective action process instead of a discrete, broad-brush application of another single point improvement tool. This is particularly true in the transactional process improvement arena. There are an unlimited number of new and undiscovered improvement opportunities in the broader and more complex interconnected network of professional knowledge-based transactional processes. Here is the big differentiator: The visible and invisible complexity of improvement increases with the level of globalization and the human professional and technology content of processes, but so does the incremental value contribution of improvement. A more responsive and reconstructive forensics approach to VSM is required in these invisible transactional processes.

Rather than beginning the VSM process with the objective of mapping the organization’s entire universe of processes, much quicker and higher value creation can be achieved with a more focused building-block approach. The objective of accelerated value stream mapping is many smaller hits in the right process pain points that achieve breakthrough results. This process aligns limited improvement resources with the highest impact improvement opportunities and promotes a more robust approach to improvement. Over time a broader VSM evolves from the smaller elements. In some cases tandem efforts are encouraged to suspect areas. As some critics have claimed, VSM does in fact view the end-to-end process, but the corrective actions are targeted to the highest-impact segments of the process. The proof is in the quicker and better results for the resources invested in mapping. Traditional VSM can often end up as a dead-end, solve-world-hunger exercise. The largest difference between the traditional and accelerataed VSM is that the mapping process becomes a more streamlined, continuous living reference to architect, reengineer, or improve enterprisewide business processes. This requires the integration of VSM with other improvement methodologies and tools and at a basic level the integration of Lean thinking (elimination of wastes) and the most basic Six Sigma problem-solving analytics.

Accelerated value stream mapping is more of a laser-targeted, rapid deployment and rapid results process that leverages the organization’s current knowledge and tall pole (Pareto) thinking. This approach is more of a surgical peeling back of the onion by several means (e.g., focus group sessions, preanalytics, evaluation of customer and internal operating data, other diagnostic activities) before any specific VSM activities begin. Here is a simple overview of the accelerated process:

Conducting the accelerated value stream diagnostic. For the process under study, the practitioner and the team develop the SIPOC+ Diagram (SIPOC/P/C/TGW/D for supplier, input, process, output, customers, performance metric, controls to maintain quality and standardization, things that typically go wrong, and supporting data) for the process under investigation (usually 6–12 steps, 1–2 pages max), and complete the remainder of the template.

Conducting the accelerated value stream diagnostic. For the process under study, the practitioner and the team develop the SIPOC+ Diagram (SIPOC/P/C/TGW/D for supplier, input, process, output, customers, performance metric, controls to maintain quality and standardization, things that typically go wrong, and supporting data) for the process under investigation (usually 6–12 steps, 1–2 pages max), and complete the remainder of the template.

Next, an extended dialogue CED (cause-and-effect diagram) is developed following the processes identified above, and the team brainstorms potential root causes of the process problem within each step. It is wise to use the white space to free-form other related issues such as barriers, broader summary root causes, interrelationships, data needs, and so on.

Next, an extended dialogue CED (cause-and-effect diagram) is developed following the processes identified above, and the team brainstorms potential root causes of the process problem within each step. It is wise to use the white space to free-form other related issues such as barriers, broader summary root causes, interrelationships, data needs, and so on.

The next step is to validate root-cause information with hard data and then eliminate the perceived causals that do not stand the test of truth.

The next step is to validate root-cause information with hard data and then eliminate the perceived causals that do not stand the test of truth.

Finally, conduct a designed force ranking analysis of the remaining root causes using frequency, severity, improvement impact, and controllability, borrowed from FMEA (failure mode and efficiency analysis) logic.

Finally, conduct a designed force ranking analysis of the remaining root causes using frequency, severity, improvement impact, and controllability, borrowed from FMEA (failure mode and efficiency analysis) logic.

Look at the top 20 percent of the force ranked root-cause scores and note which step of the process they occur in. This analysis always points to a particular step or subprocess and isolates the highest influence detractors. It focuses resources on the most important detractors within a segment of the process. This is where the remaining focus of improvement efforts are pointed.

More detailed implementation. The purpose is to analyze the highest-ranked problem process segment in more detail, integrating the traditional and more detailed VSM approaches with other simpler analytics (Pareto analysis, run charts, defects analysis, sampling plans, Cp and Cpk analysis, MultiVari, etc.) and other less structured tools (e.g., A3, mind mapping, affinity diagrams, worth factor analysis, etc).

More detailed implementation. The purpose is to analyze the highest-ranked problem process segment in more detail, integrating the traditional and more detailed VSM approaches with other simpler analytics (Pareto analysis, run charts, defects analysis, sampling plans, Cp and Cpk analysis, MultiVari, etc.) and other less structured tools (e.g., A3, mind mapping, affinity diagrams, worth factor analysis, etc).

The analytics lead to developing, calibrating, and recommending opportunities for improvement, and developing the detailed implementation plans and control plans.

The analytics lead to developing, calibrating, and recommending opportunities for improvement, and developing the detailed implementation plans and control plans.

Next, the team implements the improvements and monitors process performance.

Next, the team implements the improvements and monitors process performance.

For those who have difficulty with constructing a large map, remember that this is an iterative process where the puzzle pieces eventually come together as a whole. The largest benefit to accelerated value stream mapping is that organizations are dealing with real problems in the real process in real time.

Note that accelerated value stream mapping is not created in a single lengthy task with one tool. Such an approach usually ends up as wasteful fishing expeditions. Accelerated value stream mapping is many smaller cycles of “map-calibrate-prioritize-improve-validate,” combined with broader and more robust analytics. The objective is not to issue a vague directive to create a map and see where the problem areas lie. An incorrect, out-of-date, big picture VSM of the entire organization is not very useful to support continuous improvement efforts. The objective is to improve problem areas that are well recognized by the people who work within the process every day. This rapid deployment approach leverages associate knowledge and experience, directly engaging people where they work in the improvement process, and validating opportunities with data and facts. We are creating detailed segments based on highest-impact opportunities. The size of the segment is relative to the interconnectivity of the process segment under investigation (manageable “chunks” for rapid improvement), but it is never a megadocumentation exercise of every process in the entire organization. Accelerated value stream mapping involves deep diving into the largest detractor process segments and understanding the factors that really make the overall process tick. Over a relatively short period of time, the process segments can be pieced together to present a larger picture of the organization. Another reminder: In this scenario VSM is but a single tool in the broader improvement toolbox and a living process of improving how you improve.

Transactional process improvement represents the missed mark of Lean in many organizations that continue to operate with excess hidden wastes, costs, time delays, quality problems, and major customer issues. Despite the Lean and general continuous improvement (CI) investments of the past, organizations certainly deserve and can achieve significant value contribution in transactional process improvement. In fact, transactional process improvement represents the highest hidden area of opportunity in many organizations that continue to work with their institutionalized IT architectures and related business processes.

Why should organizations be all over the topic of transactional process improvement? The benefits of transactional process improvement are enormous—larger than Lean manufacturing—because they often involve fixing problems that are the root cause of manufacturing issues, fixing problems that the organization does not know about yet, or fixing problems that as stand-alone efforts can easily run to tens of millions of dollars in new value. Think about the cost of excess/obsolete inventory, returns and allowances, late time-market, poor outsourcing decisions, or ineffectual innovation, just to name a few. The following is a partial list of transactional process improvement initiatives where our clients have achieved significant benefits:

Strategic planning and business alignment

Strategic planning and business alignment

Customer and market research

Customer and market research

Product and market strategy

Product and market strategy

Product management and SKU rationalization

Product management and SKU rationalization

New product innovation and concept engineering

New product innovation and concept engineering

New product development and time-to-market

New product development and time-to-market

Global commercialization, packaging, literature

Global commercialization, packaging, literature

Warranty, returns, and allowances

Warranty, returns, and allowances

Invoicing and billing errors

Invoicing and billing errors

Excess/obsolete inventory reduction and reserves

Excess/obsolete inventory reduction and reserves

Requests for quotations (RFQs)

Requests for quotations (RFQs)

Customer service, repair, spares management

Customer service, repair, spares management

Global sourcing and outsourcing

Global sourcing and outsourcing

Financial adjustment, variance, close reduction

Financial adjustment, variance, close reduction

Outsourcing rationalization

Outsourcing rationalization

Advertising, marketing, and promotions

Advertising, marketing, and promotions

Sales and operations planning (S&OP)

Sales and operations planning (S&OP)

Supply chain execution and control

Supply chain execution and control

Distribution, transportation, and logistics

Distribution, transportation, and logistics

Supplier development and management

Supplier development and management

Selling and account/channel management

Selling and account/channel management

Organizational development and human resources management

Organizational development and human resources management

Global real estate and space management

Global real estate and space management

Strategic maintenance and facilities management

Strategic maintenance and facilities management

Performance measurement processes

Performance measurement processes

Information technology effectiveness and ROI

Information technology effectiveness and ROI

Acquisition and integration process

Acquisition and integration process

Copyright © 2015, The Center for Excellence in Operations, Inc.

The remainder of this chapter provides guidance about how to rethink and how to adapt a Lean Business System to the interconnected global networks of complex, professional knowledge-based transactional processes and achieve renewed breakthroughs in operating performance.

The first step to success is to understand and appreciate the nature of transactional processes. Manufacturing, from which many Lean and general process improvement techniques evolved, represents a declining percentage of the end-to-end economic and strategic process activities in organizations. Sure, manufacturing is still part of the value chain, but a very small component in terms of the fully loaded process costs of doing business globally. Many organizations have morphed themselves from geographically and country-specific physical sites to a global network of complex, knowledge-based transactional processes. Yet their Lean resources are dated in attempting to port over the approaches that worked well on the production floor and thinking about eliminating rather than integrating information technology. The operating environments in organizations have changed faster than the capacity and capabilities of their resources to improve it. Walking off the production floor and into the offices of very talented professionals with the same narrow, tools-based Lean thinking is a prescription for disaster. Success is highly dependent upon a paradigm shift to nimble and efficient strategy and opportunity alignment processes, supply chain processes, time-to-market processes, cash-to-cash processes, engineering processes, customer service processes, sales and marketing processes, and many other “people plus technology” processes in organizations. As the number of professional knowledge workers and technology content increase, the complexity of transactional processes increases, the degree of difficulty of improvement and change increases, and the usefulness of the Lean manufacturing tool-set thinking decreases.

By comparison, Lean manufacturing is simple. Even the most commoditized tool-set approaches to Lean manufacturing produce temporary results. Transactional processes are much more complicated because of their interconnected, convoluted, and cross-enterprise processes, lack of standardization, unsighted activities, velocity and touch points, and of course the human element of originality and work-arounds in daily operations. So why has Lean failed to deliver in these strategic and mission-critical business processes? Because transactional processes require a higher order of improvement with an integrated approach. The Lean principles and tools that produced success on the production floor are success limiting in human-dependent transactional process environments. As we mentioned previously, transactional improvement cannot rely upon normal senses to identify issues and new opportunities for improvement that is possible on the production floor. One can observe physical bottlenecks, measure defects, view excess inventory, listen to equipment vibration, detect odor from poor ventilation systems, and the like. Transactional process opportunities are hidden in the human and information architectures of organizations. One cannot see an IT transaction or observe a human thinking bottleneck, or sniff end-of-month general-ledger adjustments—or readily define and measure defects and root causes. In the absence of hard data and facts, transactional processes are managed via opinions, perceptions, cursory explanations, and political deflections that lead to quick symptomatic responses.

We also mentioned value stream mapping earlier in this chapter. Lean practitioners have relied too heavily on a canned, single-point methodology in the transactional process space. For example, many organizations have spent months conducting blind value stream mapping exercises of the entire company with no purpose or specific problem in mind (“Field of Dreams” improvement—if you map the process, the problems and solutions will automatically happen). Value stream mapping is one of the most useful improvement tools, but it needs to be adapted to the megahertz transactional process environment. Transactional process improvement also requires a much deeper view of Lean thinking, approach, analysis, information, and measurement systems. It requires a broader blend of improvement thinking, methodologies, and technologies. In the absence of a proactive, well-planned and well-executed transactional improvement effort, organizations cannot manage and prevent problems. Instead, they are forced into a mode of detecting and reacting to problems after the fact—and that is too late (e.g., disconnects in supply and demand, returns and allowances, supplier delivery and quality issues, late new product development tasks, buried financial variances, excess/obsolete inventory, write-offs and adjustments, billing errors, customer complaints, etc.). This is not acceptable because these wastes are assignable and correctable. Organizations that are willing to launch an all-out aggressive campaign against transactional process waste with the right holistic approaches will find new money—millions of dollars of new and previously unknown opportunities for improvement. It requires putting the Lean keys down for a minute and rethinking the journey with the right competencies, resources, and approach.

One thing is for certain: The philosophy and mindset of Lean are directly applicable to complex transactional processes, but the planning and execution are very different. Adapting Lean to the complex realities of transactional processes is not straightforward. Success involves putting away the traditional bag of Lean principles and tools and thinking outside the box. Here are a few points to consider when adapting Lean to a more robust Lean Business System environment:

1. First, improvement practitioners and other resources must develop a deep understanding of how to adapt Lean to extremely nonconventional and highly complex processes and environments. Simply attempting to overlay the commoditized Lean tools that worked well in manufacturing is dead wrong and doomed to failure.

2. Second, improvement practitioners and other resources must develop a deeper understanding of the organization’s complete information architecture and the specific knowledge-based “people plus technology” core business processes that are embedded within the overall architecture (e.g., ERP, BOMs, financial systems and G/L, inventory management and accountability, receiving, sales systems and account management, HR systems, warranty and returns, invoicing and collections, order fulfillment, patient admitting and scheduling, and other system architecture applications). The right team composition is a mandate for success.

3. Third, this transactional process improvement requires a high degree of creativity and innovation. The objectives may be the same (e.g., eliminate waste, improve process quality, align with customer requirements, velocity, asset and human capital optimization, etc.), but the execution is typically created to achieve a specific purpose. There are no invoicing error or inventory variance or failed design verification or incorrect behavior and culture deficiency Lean tools. Transactional processes require experimental re-creations, replications, and simulations of problems using the combined knowledge, wisdom, experiences, and data of highly competent professionals that live the process every day. Tracking down and eliminating the root causes of waste is often analogous to an accident or crime scene investigation.

4. Fourth, transactional process improvement requires measurement system analysis (MSA) and other analytics in parallel with process analysis. Many issues in transactional processes can be directly pegged to the mechanics of how performance is measured—and not measured. Transactional processes have root causes embedded in both the measurement system and the process itself.

One might argue that this is overkill. It definitely is not, and the oversimplification and underestimation of transactional process complexity is why organizations have not achieved the benefits that they deserve through a traditional Lean manufacturing tool-set approach. Fact is, all of these “people plus technology” transactional processes are interconnected and interdependent professional processes. Silo-based improvements will actually create more waste and inefficiencies in the business. The right cross-functional improvements will produce both direct and residual benefits throughout the business. Transactional processes are much more dynamic and subject to change than a machine on the production floor. They require true continuous monitoring and improvement to keep the waste from returning.

Over the years we have referred to transactional process improvement as transactional forensics. No, the evidence may not be used in a court of law (although we have been involved in expert testimony work in the past), but the process of digging out the truth about what really happened is very similar. Complex transactional processes include a lot of unpredictability, professional judgments versus hard data, a high degree of informal activities underlying a formal process, and fuzzy cause and effects in space and time. In this example judgment is not a casual opinion—it is verifiable and sufficient cause of clue data. Lean forensics entails bringing scientific order to the ways and means that one manipulates and tests the speculative causes and effects in transactional processes, which opens up the door to improvement and greatly reduces the risk of drawing false conclusions. Too many executives and professionals view transactional processes as “the way it is” and are not motivated to change them. They fail to see the enormous benefits of data mining, analytics, and transformation. The seasoned improvement expert uses the organization’s integrated enterprise architecture and other applications to trace and defrag the transaction trail like a forensic detective reconstructing and processing a crime scene to identify root causes and other existing conditions during the actual event. In practice, the differences between root causes and outcomes are often fuzzy (the reflexivity factors), and the challenge becomes one of identifying and isolating the right, most severe detractor segments of these transactional processes with facts. Success requires a deep understanding of both improvement and key business processes.

This is how and why we developed accelerated value stream mapping. Organizations can map the end-to-end transactional processes, but they cannot improve them end to end because causes and effects are overlapping and relative in time and space. What is meant by this statement? Here is an example: Ask managers and associates in the sales, S&OP, manufacturing, engineering, purchasing, quality control, distribution, and finance organizations why there is so much obsolete inventory, and you will receive at a minimum, eight different answers—most likely dozens of conflicting and finger-pointing opinions and perceptions. The real story and root causes are buried and unknown to the organization. By the way, how do organizations normally “fix” this problem? They allocate financial reserves for future write-offs. Does that address and eliminate root causes? What happens next year and the year after that? Does obsolete inventory go away? Absolutely not! The seasoned improvement is able to mine and construct the real story and root causes, and in the majority of cases they are totally different from everyone’s perceptions and opinions. Trying to improve an end-to-end transactional process often turns into symptomatic problem solving. These transactional issues are complex. Often these situations require deeper skills and approaches than a team has that is introduced to VSM and being coached to follow the recipe and standard symbols verbatim. It comes back to the axiom, You don’t know what you don’t know. This is not your traditional Lean or Six Sigma practitioner at work; it’s a bit analogous to how one might expect a Henry Lee and Michael Baden to conduct an improvement initiative.

Currently there exists another huge missing link between human Lean talent development and the evolving technologies such as cloud computing, event-driven performance dashboards, business analytics, and data visualization. Many Lean practitioners remain in the Stone Age holding onto their magnetic scheduling systems, manual production boards, and other manually maintained Lean practices. Some continue to see technology architectures as inhibitors rather than enablers of Lean, especially in an enterprisewide Lean Business System. Others have a comfortable, fixed focus on Lean manufacturing. On the IT side of the house practitioners implement the technology first and then come back to business process improvement at a later date. Improvement can be viewed as an impediment to quick technology spending and implementation. The game has changed for everyone in every organization. Technology-enabled improvement plays a key role in transactional process improvement. Transactional improvement is transparent and composed of key business processes, information flows, knowledge-based employees, and complex, contradictory decisions. There are literally hundreds of professional and knowledge resources managing thousands of dynamic process touch points, a continuous churn in changing requirements, specific country needs, time constraints, communications issues, and exponentially greater opportunities for waste, variation, human risk, and bad decisions. Technology enables the sophisticated Lean practitioner to see these wastes and the true root causes through a virtual reconstruction of the processes and conditions that create the wastes. Particularly in the transactional process improvement space, one finds several consistently recurring situations:

Different executives, managers, and associates have different perspectives and ideas about the problem and its root causes, and in most cases nobody including the Lean expert knows the real problem (“You don’t know what you don’t know”).

Different executives, managers, and associates have different perspectives and ideas about the problem and its root causes, and in most cases nobody including the Lean expert knows the real problem (“You don’t know what you don’t know”).

Often, what was thought to be the problem is not a problem at all, but symptomatic of deeper waste activities buried in the complex transactional process network.

Often, what was thought to be the problem is not a problem at all, but symptomatic of deeper waste activities buried in the complex transactional process network.

In almost every case, what was thought to be the root cause of a transactional process problem is incorrect, and turns out to be a totally different and unknown root cause once the onion is peeled back and the transactional process is stripped butt naked.

In almost every case, what was thought to be the root cause of a transactional process problem is incorrect, and turns out to be a totally different and unknown root cause once the onion is peeled back and the transactional process is stripped butt naked.

All improvements require a combination of analytical methodologies, and all improvements typically include a combination of people, process, and technology (e.g., training and education, process improvement, technology-enabled enhancements).

All improvements require a combination of analytical methodologies, and all improvements typically include a combination of people, process, and technology (e.g., training and education, process improvement, technology-enabled enhancements).

Technology is a huge game changer in a transactional process-intense Lean Business System environment because it is transforming the whole discipline of improvement and how organizations improve how they improve. Technology is also simplifying the design, focus, maintenance, and measurement of the entire Lean Business System architecture.

As we say throughout the book, if an organization has a Lean initiative in place, chances are that it is missing the mark on the total opportunities of transactional process improvement. Forget about thinking failure. Many of these new and unknown opportunities exist because the world has changed. If your organization is one of the success stories, then congratulations! If your organization is in the majority segment of organizations that are underperforming in the Lean transactional improvement space, there may be many reasons for this but they are irrelevant when compared to the enormous opportunities for improvement and competitiveness that exist. Several organizations have their Lean Business System in name only; it is really a success-limiting production system with a broader label. It requires a lot more than a 5S exercise, A3 templates, and a modified production board to uncover and harvest these complex opportunities. There should be absolutely no question at this point about the differences between a Lean Production System and a real, enterprisewide Lean Business System—and the significant differences in upside potential for value contribution.

The Lean Business System Reference Model is the guide to a new and much larger beginning with Lean. Improvement via innovative thinking and enabling technology often results in total process and business model reinvention. Transactional process improvement is undiscovered territory for Lean and represents tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars in new value contribution for many organizations. Think about the short-term P&L impact and the longer-term competitiveness of:

Reducing returns and allowances by $30 million.

Reducing returns and allowances by $30 million.

Improving time to market by 80 percent and being number one in the market.

Improving time to market by 80 percent and being number one in the market.

Adding three or four gross margin points to the P&L through less planned financial reserves.

Adding three or four gross margin points to the P&L through less planned financial reserves.

Reducing supply chain time, complexity, and costs by $100 million.

Reducing supply chain time, complexity, and costs by $100 million.

Gaining hundreds of millions of revenue growth, cost reduction, profitability, and competitive market position from developing new products on time, on budget, without post-release quality, reliability, or performance problems.

Gaining hundreds of millions of revenue growth, cost reduction, profitability, and competitive market position from developing new products on time, on budget, without post-release quality, reliability, or performance problems.

Reducing the financial close and all related G/L clerical adjustments and clerical resource needs by 75 percent.

Reducing the financial close and all related G/L clerical adjustments and clerical resource needs by 75 percent.

Reducing engineering changes by 50 percent.

Reducing engineering changes by 50 percent.

Hitting new product features/functions out of the park with customers—like the emotional Apple, Porsche, and Harley Davidson customer experiences.

Hitting new product features/functions out of the park with customers—like the emotional Apple, Porsche, and Harley Davidson customer experiences.

Reducing travel expenses by $6 million and reducing the need for limited resources to travel internationally to put out fires.

Reducing travel expenses by $6 million and reducing the need for limited resources to travel internationally to put out fires.

Improving advertising and promotion effectiveness by 100 percent.

Improving advertising and promotion effectiveness by 100 percent.

Reducing operating supplies and facility costs by $10 million.

Reducing operating supplies and facility costs by $10 million.

These are actual transactional process improvements achieved in organizations. The challenges are much greater, but so too are the opportunities for improvement. Beyond the numbers, transactional process improvement provides an extremely challenging and professionally rewarding leadership and general business growth experience. Organizations can really accelerate talent and organizational development by engaging people in a variety of experiences in different functional areas. Over time this builds knowledge and an appreciation of other people’s roles in the organization, increases the broader core business process thinking, and helps to create the right behavioral patterns and cultural attributes for enterprisewide success.

Burton, T. 2010. Accelerating Lean Six Sigma Results: How to Achieve Improvement Excellence in the New Economy. J. Ross Publishing, Boca Raton, Florida.

Burton, T. 2013. Abstraction Factor Analysis: A New Approach to Improve New Product and Software Development. CEO Executive White Paper series. http://ceobreakthrough.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Abstraction-Factor-Analysis.pdf.

Burton, T. 2013. “Faster Value Stream Mapping,” Industrial Engineering Magazine, June 2014. Norcross, Georgia.

Burton, T. 2013. Lean Six Sigma in Healthcare. CEO Executive White Paper series. http://ceobreakthrough.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Lean-Six-Sigma-in-Healthcare-.pdf.

Burton, T., and Filipiak, E. 2011. Improvement Excellence in the Federal Government: Addressing the Urgent Need to Reduce Waste and Deficit Spending, and Improve Service Delivery. CEO White Paper Series. http://ceobreakthrough.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/CEO-Website-Government-Waste-White-Paper-Part-1.pdf.

Navarro, P., and Autry, G. 2011. Death by China: Confronting the Dragon—A Global Call to Action. Pearson Education, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

Steelcase. 2012. “Culture Code: Leveraging the Workplace to Meet Today’s Global Challenges,” Steelcase 360 Magazine, iss. 65.