Figure 5.1 Author with Minister-Counselor Jiang Qin at China’s Mission to ASEAN, Jakarta

Source: Author’s photo

“China is committed to pursuing partnership with its neighbors and a neighborhood diplomacy of amity, sincerity, mutual benefit and inclusiveness, and fostering a harmonious, secure, and prosperous neighborhood.”

—China’s President Xi Jinping, Singapore, 2015.1

“China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact.”

—China’s Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi, Hanoi, 2010.2

“The Chinese government has not decided to break up ASEAN. . . . Yet its actions have weakened ASEAN, a dangerous thing to do to an organization that is inherently fragile—perhaps as fragile as a Ming vase.”

—Kishore Mahbubani, National University of Singapore, 2016.3

China’s relations with Southeast Asian countries and ASEAN have grown dramatically since the turn of the twenty-first century and have now achieved a high degree of interactions. Some statistics are illustrative. By 2018 ASEAN’s total trade in goods with China had expanded to $587 billion, China’s total foreign direct investment (FDI) into ASEAN increased to approximately $84 billion with annual $13.4 billion inflows, Chinese tourist arrivals in ASEAN totaled 20.3 million people and over 38 million trips were taken in both directions, over 200,000 students are studying in each other’s universities (80,000 Southeast Asian students are enrolled in Chinese universities with 124,000 Chinese students in ASEAN universities), more than 3,000 flights shuttle back and forth every week, and a variety of other indicators reveal a considerable density of interactions.4 There has been a particularly notable uptick in all spheres since around 2015 (pre-COVID-19).

China’s contemporary approach toward Southeast Asia is shaped by multiple factors. Among them, perhaps geography is the most important. China’s close geographical proximity facilitates easy access and regular presence. This has led to growing economic interconnectedness, buttressed by transportation links. This relative proximity also facilitates tourism, academic exchanges, and a regular presence of Chinese officials visiting the region.

How does China perceive Southeast Asia and the dynamics in the region, and what does it reveal about Beijing’s strategy toward the region? A sampling of recent publications by China’s Southeast Asia specialists, combined with official documents, is revealing on a number of levels.

First, it must be said that there is surprisingly sparse expertise on Southeast Asia in China. This is a curious anomaly given the relative importance of the region to China. Compared with other academic disciplines focused on regions of the world (such as American Studies, European Studies, African Studies, Latin American Studies), Southeast Asian Studies in China today is relatively underdeveloped.5 This is not to say that the field is in any way absent, but I find it underdeveloped when compared with these other area studies. This is particularly the case in Beijing. There is, for example, no separate institute for Southeast Asian Studies in the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). Other Beijing think tanks—such as the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (Ministry of State Security) and China Institute of International Studies (Ministry of Foreign Affairs)—generally only have a couple of researchers each devoted to the entire region (who tend not to speak regional languages), and they tend to concentrate on security issues rather than domestic affairs, foreign relations, or ASEAN itself.6 Occasionally, faculty at China Foreign Affairs University (CFAU) publish on Southeast Asia, although the university has no dedicated institute (the same applies to Peking University, Renmin University, and Tsinghua University—all of which have established international relations and a variety of other regional studies programs).7 Thus, there is a real dearth of expertise on Southeast Asia in the capital city.8

Conversely, the strengths of Southeast Asian regional studies lie outside of Beijing. There are several universities in the southern part of the country that have institutes or programs of Southeast Asian Studies: at Jinan University (Guangzhou), Xiamen University, Yunnan University, Guangxi University, Guangxi Normal University, and Zhongshan University. Research in these institutions tends to be heavily oriented toward ethnographic, historical, and cultural studies (including overseas Chinese), with some social science or international relations work being undertaken. The exceptions to this rule are Xiamen University and Jinan University (Guangzhou), which are more comprehensive in scope and publish the two leading contemporary studies journals in China, Southeast Asian Affairs (南洋问题研究)9 and Southeast Asia Research (东南亚研究) respectively. The Yunnan and Guangxi Academies of Social Sciences also each have research institutes on Southeast Asia, the first of which has published a number of volumes on contemporary Southeast Asian affairs.10 Despite these pockets of expertise, I am still struck by the dearth of expertise in universities and think tanks given the size, proximity, and importance of Southeast Asia to China.

Of these institutions, the Research School for Southeast Asian Studies in the College of International Relations at Xiamen University in Fujian is the oldest and best in China. The beautiful Xiamen University campus is nestled seaside, where the island of Jinmen (Quemoy) is visible just 2 miles offshore. Jinmen was the site of high tensions in the period 1954–1960, when it was aptly described as the “frontline of the Cold War” (along with Berlin), as it was the forwardmost military outpost of the Chinese Nationalists (with 58,000 soldiers deployed on the tiny island) after they retreated to Taiwan. Jinmen was the epicenter of two Taiwan Straits crises of 1954–1955 and 1958–1960 when Chinese Communist forces began artillery shelling of the island (along with neighboring Matzu), thus triggering US military responses (and fierce debates between Kennedy and Nixon during the 1960 presidential election). In the midst of these crises the central government ordered the establishment of the Nanyang Research Institute (南洋研究所) at Xiamen University in 1956, to concentrate on the study of overseas Chinese and Southeast Asia. In 1974, following clashes with South Vietnam over some disputed islands in the Paracel chain (which China seized following brief firefights), the institute took on the added research responsibility for South China Sea studies. In 2000 the Ministry of Education elevated it to the status of “key point” (中点) national research center (研究院). Thereafter, the institute broadened its focus to international relations of the region and established eight specialized research centers including an ASEAN Studies Center. When I visited the school in October 2019, as part of researching this book, I was impressed by the quality of the faculty and earnestness of the student body (over 400). Its 25 faculty offer a range of regional courses for BA, MA, and PhD concentrations, the library has an extensive collection of over 100,000 volumes, and the school engages in multiple exchanges with institutions in Southeast Asia.

In terms of analytical tendencies, Chinese analysts of Southeast Asia evince several. First, they tend to adopt a big power approach and thus are preoccupied with the role of the United States—and China’s competition with it—in the region. Part of this perspective is related to China’s desire to create its own sphere of influence in the region, while part of it is related to China’s defense posture of trying to push the US military as far away from its shores as possible.

This tendency in Chinese publications is also a by-product of Chinese scholars’ readings of American analyses, as they show considerable familiarity with US scholarship (ironically, however, they do not often reference Southeast Asian scholarship). There is thus not a great deal of originality in Chinese writings, as many tend to repackage or cite Western scholarship. Second, however, Chinese scholars do carefully monitor the cohesion and orientation of ASEAN—for any signs that the grouping is developing in an anti-China direction. Conversely, Chinese observers are keenly aware of ASEAN’s frequent and systemic disunity—and prefer to keep the organization that way. A unified ASEAN has the potential to be oriented against Chinese interests, while a disunited ASEAN is more malleable and easily manipulated by Beijing.

Yet some Chinese analysts are particularly critical, even scathing, in their assessments of ASEAN. Some see it as a weak organization and dismiss “ASEAN Centrality” as a mere slogan. On the occasion of ASEAN’s 50th anniversary in 2017, one analyst in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs–affiliated China Institute of International Studies noted four systemic weaknesses of ASEAN: (1) “Building of the ASEAN Community is still flawed”; (2) “ASEAN has not solved the problem of internal leadership”; (3) “ASEAN’s ability to coordinate with its dialogue partners is limited”; and (4) “ASEAN’s performance in promoting regional cooperation remains to be improved.”11 Despite these criticisms, this analyst and other Chinese observers always maintain that “China always attaches great importance to its cooperative relations with ASEAN . . . and accepts ASEAN’s central role in regional cooperation.”12

Overall, though, Chinese analysts see an increasingly competitive strategic dynamic between the United States and China across the Indo-Pacific region, but particularly in Southeast Asia.13 This is not a new dynamic, as Chinese strategic analysts have been arguing that regional strategic competition (地区战略竞争) and structural contradictions (机构性矛盾) began to rise during the Obama administration.14 Many articles accused the Obama “pivot” or “rebalance” policy as thinly veiled “containment” (遏制). While many Chinese analysts see the renewed American attention to Southeast Asia as beginning with the Obama pivot, many think the competition has continued under Trump.15 One analyst from Xiamen University acknowledged that the increased attention paid to Southeast Asia by the Obama administration did have a negative impact on “political mutual trust” (政治互信) between China and ASEAN states, and he argued (in 2014) that China needed to step up its game to win back the region’s mutual trust.16 This required a comprehensive approach involving cultural, economic, diplomatic, and institutional efforts. He also noted the sensitivities of disputed claims in the South China Sea and that “China should take care of the interests of the disputed parties while safeguarding its sovereignty but avoid establishing a unilateralist image in its diplomacy.”17

In dealing with the United States in Southeast Asia, some analysts acknowledge that some ASEAN countries support the United States in balancing against China (借美制华), though not specifying which ones, but they do argue that China still has greater “strategic capital” (战略资本) in the region than does the United States, and therefore it should exercise “strategic patience” (战略定力).18 Other authors view Southeast Asian states’ position vis-à-vis China and the United States as dependent on the country’s “capacity” and “will”:19

Considering regional characteristics, we might be able to classify the strategies of neighboring countries towards China into four distinct categories: balancing, accommodating, opportunism, and hedging. Specifically, if a neighboring state has both strong capacity and will . . . such a state will have a preference towards balancing. . . . If, on the other hand, a state only has strong capacity to balance, but is lacking in will, it will prefer accommodation. If on the other hand, a state’s capacity to balance is weak, but has strong will, it can lean towards opportunism, such as Vietnam. If a state’s will and capacity to balance are both weak, such a state is likely to follow a hedging strategy.

Some authors, though, see Southeast Asian states as trying to avoid “bandwagoning” (with Beijing) by “hedging” and trying to maintain an equidistant position between the United States and China. “An equilibrium strategy has gradually become the preferred strategy that Southeast Asian countries employ to maximize their strategic interests,” argues one author from Shanghai Foreign Trade University.20 Another argues that hedging is the “default strategy” for ASEAN states.21

Another assessment by a scholar at the China Foreign Affairs University divides ASEAN countries into three types in terms of their approaches toward China: friends and collaborators; enemies and opponents; and uncertain hedgers.22 The first group are those countries that have largely been “absorbed into China’s economic system” (Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos). The second group seek to “counterbalance China,” mainly by aligning with the United States (Singapore, Vietnam, Philippines). These countries seek to “befriend distant states” (远交), but not “attack those nearby” (近功). However, the author sees this tendency declining as the “China threat theory voices are slowly disappearing in the mainstream Southeast Asian countries.” The third group are those practicing the two-dimensional “hedging strategy” (两面注战略)—Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. This last group seeks a relationship between ASEAN and China that is “not close but not distant” (不远不近) and “neither friend nor enemy” (非敌非友).23 This author concludes that in the fluid environment of Southeast Asia, China should prepare for surprises in its relations with Cambodia and Myanmar as “problems may arise,” but that there is no need for undue pessimism about relations with Vietnam and the Philippines, and that China’s wisest approach is to actively engage in ASEAN’s multilateralism.24

Many other authors think that China holds natural appeal in the region. Some hark back to the October 2013 Peripheral Diplomacy Work Conference and argue that continued attention to China’s neighborly policy of “amity, sincerity, mutual benefit, and inclusiveness” should be sufficient to assuage the region,25 while others hold that Xi Jinping’s “China-ASEAN Community of Common Destiny” is of intrinsic attraction.26 Yet others question this optimism, arguing that while China enjoys extensive economic complementarities with Southeast Asia, there simultaneously exists considerable political mistrust and friction, which have compromised Chinese diplomatic initiatives.27 Moreover, this author, who is identified as working at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Asia-Pacific and Global Strategic Research Institute, argues that China’s soft power (软实力) has not been very effective in changing the “strategic mentality” (战略性思潮) of ASEAN.28

Others, sensing more urgency, argue China has to be particularly “vigilant” against US inroads—especially in Indochina and the lower Mekong region.29 Chinese military analysts point to strengthened military ties between the United States and India, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines.30 One PLA researcher at the National Defense University Institute of Strategic Studies meticulously catalogued the range of joint military exercises the United States carries out in the region: Cobra Gold (multinational based in Thailand), CARAT (multinational conducted in South China Sea), Balikatan (Philippines), Angkor Sentinel (Cambodia), Cope Tiger (Singapore, Thailand), and Strikeback (Malaysia). He also surveyed Foreign Military Sales (FMS) arms transfers and the International Military Education Training (IMET) officer training program.31 One article by professors at the Public Security University in Beijing carefully traced the history of IMET with the Indonesian military (one wonders if IMET is a model for what the PLA aspires to in its foreign military assistance in the future?).32 Also of particular interest to Chinese military analysts was the April 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (ECDA), concluding that it permitted the US military to be “almost permanently stationed in the Philippines.”33 Others argued that the best way to blunt US encirclement was not militarily—but to deepen the region’s economic dependency on China,34 and to leverage China’s comparative advantages by stepping up its “economic diplomacy” in the region.35

While Chinese publications on Southeast Asia do exhibit a preoccupation with the roles of the United States in the region, and the positioning of ASEAN member states in this great power competition,36 there are also analyses of more discrete topics. Quite a number focus on trade and investment patterns in the region.37 The annual “Blue Book” on Southeast Asia, published under the auspices of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, concentrates entirely on economic trends in the region.38 A few analysts write about domestic politics in some Southeast Asian states,39 and some analyze the South China Sea disputes. But very little, if any, is written about cultural issues, social trends, demographics, religion, ethnicity (other than overseas Chinese), terrorism or successionist movements, or other internal affairs of Southeast Asian societies. As a result, admitted Dean Li Yiping of Xiamen University, “We know a lot about economics, overseas Chinese, and current events—but we do not have a very good understanding about how and why things occur.”40 Thus, China’s Southeast Asianists exhibit pockets of specializations, but do not demonstrate through their publications either very broad or very deep understanding of the region.

Beyond perceptions, how does China actually interact with Southeast Asia? China has been steadily extending and deepening its presence throughout the region in recent years. In doing so, it has used diplomatic, cultural, economic, and security instruments in its “toolbox.”

Bilaterally, China maintains a consistent and thick set of high-level exchanges with ASEAN member states. Beijing prioritizes its relations with Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Singapore and Vietnam are secondary priorities. Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar are of lower priority (although Cambodia can be characterized as a client state).

As Table 5.1 indicates, China’s bilateral diplomatic relations have been established at different times over the past seventy years, and thus have developed at different intensities.

Table 5.1 China’s Bilateral Diplomatic Relations in Southeast Asia

| Country | Establishment of Diplomatic Relations |

| Democratic Republic of Vietnam | 1950 |

| Republic of Indonesia | 1950 |

| Union of Burma (Myanmar) | 1950 |

| Kingdom of Cambodia | 1958 |

| Kingdom of Laos | 1961 |

| Malaysia | 1974 |

| Republic of the Philippines | 1975 |

| Kingdom of Thailand | 1975 |

| Republic of Singapore | 1990 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 1991 |

| Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste | 2002 |

Today there is a very high degree of interactions. In his study of China’s regional bilateral diplomacy from 2013 to 2017, American scholar Eric Heginbotham found there are an average of 4.4 high-level (president, vice president, premier, state councilors, foreign minister) visits per country per year, with Indonesia, Cambodia, and Vietnam topping the list.41 From 2003 to 2014 there were ninety-four Chinese leadership visits to ASEAN countries, sixty-two of which occurred between 2009 and 2014.42 Every year, a number of Southeast Asian leaders are also invited to Beijing for lavish state visits. In 2017 every single Southeast Asian leader visited Beijing.43 Before his fall from power in 2018, Malaysia’s Najib Rizak was a frequent visitor (and recipient of Beijing’s financial largesse). Singapore’s Lee Hsien Loong also visits annually, and Cambodia’s Hun Sen as well. Xi Jinping has also made concerted efforts to court Aung San Suu Kyi and Joko Widodo since they became Myanmar’s and Indonesia’s heads of state, respectively, and they too have realized the imperative of dealing with China. In Myanmar’s case, one Yangon-based expert observed to me: “Aung San Suu Kyi has made her peace with China. She knows she cannot afford to alienate China. But she doesn’t have any kind of China strategy or policy, and there are zero China experts in the government.”44

The greatest diplomatic triumph for China, however, came with the much-ballyhooed visit by Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte to Beijing in November 2016, where he announced his country’s “separation” from the United States and the beginning of a “special relationship” with China. Since then Duterte has made four more official visits to Beijing in the course of just three years—in search of Chinese investment, infrastructure, and commercial trade.

Bilateral meetings between President Xi Jinping or Premier Li Keqiang are also often piggybacked on to multilateral ASEAN gatherings. Seven ASEAN heads of state were among the 29 leaders and 1,500 delegates to participate in the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in May 2017. The Chinese Communist Party’s International Department also engages in exchanges with some ASEAN countries (notably, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Vietnam). China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi and State Councilor Yang Jiechi also regularly interact with their counterparts, usually in multilateral settings. In sum, there is a high tempo of bilateral diplomatic interactions between China and Southeast Asian states.

In more recent years, China has established a range of different types of partnerships with each country (Table 5.2). Half of these were upgraded and harmonized (in terms of language) during 2018.

Table 5.2 China’s Diplomatic Partnerships in Southeast Asia

| Country | Type of Partnership | Year Established/Upgraded |

| Brunei Darussalam | Strategic Cooperative Partnership | 2018 |

| Cambodia | Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership | 2018 |

| Indonesia | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2013 |

| Laos | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Cooperation | 2018 |

| Malaysia | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2013 |

| Myanmar | Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership | 2012 |

| Philippines | Relationship of Comprehensive Strategic Cooperation | 2018 |

| Singapore | Comprehensive Cooperative Partnership Progressing with the Times | 2015 |

| Thailand | Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership | 2012 |

| Vietnam | Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership in the New Era | 2018 |

| ASEAN | Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity | 2003 |

Multilaterally, in 1996 China became a full and official “dialogue partner” of ASEAN, beginning a process of annual China-ASEAN summits. ASEAN’s other official “dialogue partners” are Australia, Canada, the European Union, India, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, Russia, and the United States—but in August 2019 at their annual ASEAN-China ministerial meeting in Bangkok, the ASEAN foreign ministers proclaimed China to be the “most important” of all of the association’s dialogue partners.45 Back at the seventh summit in October 2003, the two sides first established a “strategic partnership for peace and prosperity,” which endures by this title to this day. In the same year China signed the ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC), becoming the first foreign country and ASEAN dialogue partner to do so. In 2008, China established a separate diplomatic mission to ASEAN and appointed its first ambassador to the organization. When I visited the mission in Jakarta in 2018 (Figure 5.1) Minister-Counselor Jiang Qin kindly provided a thorough briefing on China-ASEAN ties (Ambassador Huang Xilian was away), and she said that the mission is now staffed with twenty persons representing various Chinese ministries, including the PLA.46 This contrasts with the handful of officers in the US Mission to ASEAN, although when needed it can additionally call on staff in the US embassy to Indonesia, where it is physically located (the Chinese Mission to ASEAN has its own stand-alone offices separate from the Chinese Embassy in Jakarta). The disparity in staffing levels is indicative of the importance each government attaches to ASEAN.

Figure 5.1 Author with Minister-Counselor Jiang Qin at China’s Mission to ASEAN, Jakarta

Source: Author’s photo

Multilaterally, the China-ASEAN relationship is deeply institutionalized—on paper at least—including more than ten joint ministerial mechanisms and more than twenty senior official mechanisms, according to Minister Counselor Jiang. Dozens of Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) and agreements have been signed over the years in a wide-ranging variety of fields—including public health, defense, transnational crime, nontraditional security, maritime emergencies, agriculture, information and communications technology, transport and civil aviation, tourism, sanitary and phytosanitary standards, science and technology, education, youth exchanges, cultural cooperation, environmental protection, disaster management, food safety and security, intellectual property protection, small and medium enterprise (SME) development, production capacity, media exchanges, and other fields.47 Some of these areas of cooperation are bureaucratically backstopped by joint ministerial or director-general level committees, such as those noted in Table 5.3.

Table 5.3 China-ASEAN Institutions and Mechanisms

| ASEAN-China Summit |

| ASEAN Post-Ministerial Conference with China (PMC+1) |

| ASEAN-China Senior Officials Consultations |

| ASEAN-China Joint Cooperation Committee |

| ASEAN-China Free Trade Area Joint Committee |

| ASEAN-China Ministerial Dialogue on Law Enforcement and Security Cooperation |

| ASEAN-China Defense Ministers Informal Meeting |

| ASEAN-China Ministerial and Senior Officials Meeting on Transnational Crimes |

| ASEAN-China Joint Science & Technology Committee |

| ASEAN-China Science and Technology Partnership Program |

| ASEAN-China Environmental Cooperation Forum |

| ASEAN-China Business and Investment Summit |

| ASEAN-China Expo |

| ASEAN-China Cultural Forum |

| ASEAN-China Justice Forum |

| ASEAN-China Cyberspace Forum |

| ASEAN-China Business Council |

| ASEAN-China Youth Camp |

| ASEAN-China Ministerial Meeting on Youth |

| ASEAN-China Forum on Social Development and Poverty Reduction |

| ASEAN-China Transport Ministers Meeting |

| ASEAN-China IT and Telecommunications Ministers Meeting |

| ASEAN-China Health Ministers Meeting |

| ASEAN-China Senior Officials Meeting on Health Development |

| ASEAN-China Ministerial Meeting on Quality Supervision, Inspection, and Quarantine |

| ASEAN-China Connectivity Cooperation Committee |

| ASEAN-China Police Academic Forum |

| ASEAN-China Agriculture Cooperation Forum |

| ASEAN-China Customs Coordinating Committee |

| ASEAN-China Prosecutors General Meeting |

| ASEAN-China Heads of Intellectual Property Offices Meeting |

| ASEAN-China Education Ministers Meeting |

| ASEAN-China Economic Ministers Meeting |

| ASEAN-China Ministers Responsible for Culture and Arts Meeting |

| ASEAN-China Cooperation Fund |

| ASEAN-China Public Health Cooperation Fund |

| ASEAN-China Fund on Investment Cooperation |

| Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism |

| Network of ASEAN-China Think Tanks |

| ASEAN-China Center |

| China-ASEAN Environmental Cooperation Center |

| ASEAN-China Friendship Organizations Meeting |

Sources: Plan of Action to Implement the Joint Declaration on ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership for Peace and Prosperity (2016–2020); Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China and the ASEAN-China Center, 1991–2016—25 Years of ASEAN China Dialogue and Cooperation: Facts and Figures (Beijing: ASEAN-China Center, 2016); Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, China’s Foreign Affairs (2015); Xu Bu and Yang Fan, “A New Journey for China-ASEAN Relations,” China International Studies (January/February 2016): 64–78.

These areas of cooperation and interaction have been set out in two successive Plans of Action (PoA), running from 2011–2015 and 2016–2020. These are extremely detailed documents that evince the breadth, depth, and degree of institutionalization of China-ASEAN relations.48 The 2016–2020 Plan contains no fewer than 210 initiatives.49 The nineteenth ASEAN-China Summit in 2016 in Vientiane, Laos, commemorated the twenty-fifth anniversary of ASEAN-China dialogue relations and also offered an opportunity to produce a joint statement that took stock of the relationship and produced a long list of achievements and joint programs.50 There has been a clear and apparent effort on China’s part since 2016 to energize and upgrade its ties with ASEAN. Some of this new thrust may have been stimulated by the Obama pivot and renewed American attention to the region, but it more generally has grown out of the PRC’s increased emphasis on “peripheral diplomacy” (周边外交) and availability of enormous funds to spend. Whatever the stimuli, there is now considerable momentum in China’s diplomatic attention and diplomacy toward the region.

Recognizing this new momentum and the plethora of programs and mechanisms established, since ASEAN itself is much more of an association than an institution, it does not have very effective enforcement powers and thus its ability to implement these accords is actually limited by lack of resources (institutional, human, financial). Unlike the European Commission, the ASEAN Secretariat does not have a true mandate or large bureaucracy dedicated to implementing pan-regional policies and agreements—rather, implementation is often passed on to the member states for follow-through. When this occurs, it comes only with some ASEAN funding to help facilitate implementation—usually far from enough, and individual governments normally do not earmark funding for these ASEAN-wide programs themselves, and there are no real costs imposed for non-implementation. As a result, this is why ASEAN has earned a reputation as a “talk shop”—it is very good at convening (lengthy) meetings, adopting resolutions (if they can get to consensus—a big “if”), and concluding agreements with external states that are impressive on the surface but normally achieve only partial implementation.

Thus, when evaluating the broad-gauge and impressive list of mechanisms between ASEAN and China, observers should be sober about the reality of actual cooperation. Moreover, remember that ASEAN has struck these types of agreements with many countries around the world. It is simply impossible for the ASEAN Secretariat to maintain all of these exchanges in actual practice. When I visited ASEAN Secretariat headquarters in Jakarta in 2018 (Figure 5.2), the relative lack of capacity of the organization was readily apparent. As of August 2019, the ASEAN Secretariat had only 131 recruited staff representing each of ten ASEAN member countries, with an additional 237 locally recruited staff (Indonesian nationals).51 The Secretariat’s organizational structure is represented in Figure 5.3. The Secretariat itself is more of a clearinghouse and repository of information, and a convener of meetings among regional governments and external dialogue partners, but is not a supranational institution that coordinates and enforces policies and actions across its ten member states or in concert with non-ASEAN states. As the ASEAN Secretary-General Dato Lim Jock Hoi from Brunei (Figure 5.4) told me: “ASEAN will never be a supranational organization like the EU. It was never intended as such.”52

Figure 5.2 The ASEAN Secretariat

Source: Author’s photo

Figure 5.3 ASEAN Secretariat organizational structure

Source: https://asean.org/asean/asean-structure/organisational-structure-2/

Figure 5.4 Author with ASEAN Secretary-General Dato Lim Jock Hoi

Source: Author’s photo

Nonetheless, ASEAN is very good at generating a large number of meetings—something the Chinese also excel at—and these generate a large number of agreements and aspirational documents. I am by no means dismissing these as unimportant—but am simply trying to caution analysts and observers from overestimating this thicket of bureaucratic modalities and agreements. Similarly, the Chinese are very good at generating catchy phrases to depict relationships. An example is the “2 + 7 Initiative” that Premier Li Keqiang unveiled at the 2013 ASEAN-China summit in Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei.53 The first element had to do with “two fundamental principles”: to “deepen strategic trust and good neighborly relations, and to focus on economic development and expand win-win results.” Given these foundational principles, Li then recommended seven specific action items to implement in the coming years. These included signing a new China-ASEAN Treaty of Good Neighborliness and Cooperation; beginning an annual China-ASEAN defense ministers’ meeting; upgrading the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement of 2010 and reaching $1 trillion in two-way trade by 2020; expediting development of infrastructure building; expanding financial cooperation including renminbi (RMB) currency swaps, trade invoicing, and banking services; building maritime cooperation in the South China Sea; and promoting cultural, scientific, and environmental cooperation.

The 2 + 7 initiative is a clear example of China being the proactive party in pushing forward relations with ASEAN. And, it must be recognized that seven years later all but the first action item (a new treaty) and the $1 trillion two-way trade target have been achieved. Not to be content with these rapid achievements, at the ASEAN+3 foreign ministers’ meeting in 2015, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi put forth a further ten-point proposal for taking the China-ASEAN relationship to the “next level.”54 Many of these suggestions were repackaged in the 2016–2020 Action Plan already noted.

From these examples, it is clear that Beijing is trying to drive the relationship with ASEAN. This produces a certain sense of being overwhelmed and “dialogue fatigue” among member states and certainly with the ASEAN Secretariat in Jakarta.55 This is a refrain I often heard in discussions with individual governments throughout the region. One of the key challenges facing Beijing in the future, therefore, will be to more carefully calibrate these exchanges with ASEAN—as there is already a pervasive and growing sense of China’s “overwhelming” nature. China’s geographic proximity to Southeast Asia, the enormity of its governmental apparatus, its multitude of semi-governmental actors, and its unrelenting persistence can all turn out to be negatives that produce asymmetric dependencies and alienate Southeast Asians. China’s attempts to “pull” the region within its grasp actually can have the exact opposite effect of “pushing” it away.

Chinese regional diplomacy also sometimes exhibits a distinct pushiness and demanding posture. A senior Thai official described it to me this way:

Thirty-five years ago when Chinese ministers came here, they were quite humble—nowadays it’s no longer so. China now has power, and they are acting like it—they come here and tell us to do this and do that. The Chinese have a saying: “The sky is high and the emperor is far away.” But the emperor is not so far away now. The emperor now has both the will and capability to enforce its desires.56

Bilahari Kaukisan, the former high-ranking Singaporean diplomat, further observes:

Chinese diplomats also whine about ASEAN “bullying” China or “ganging up” against China. All ten members of ASEAN combined are smaller than China. This absurd complaint is, in effect, a threat. It sets up a false dilemma as if ASEAN’S only choice is to agree with China or be against China, with the obvious insinuation that this would be unwise.57

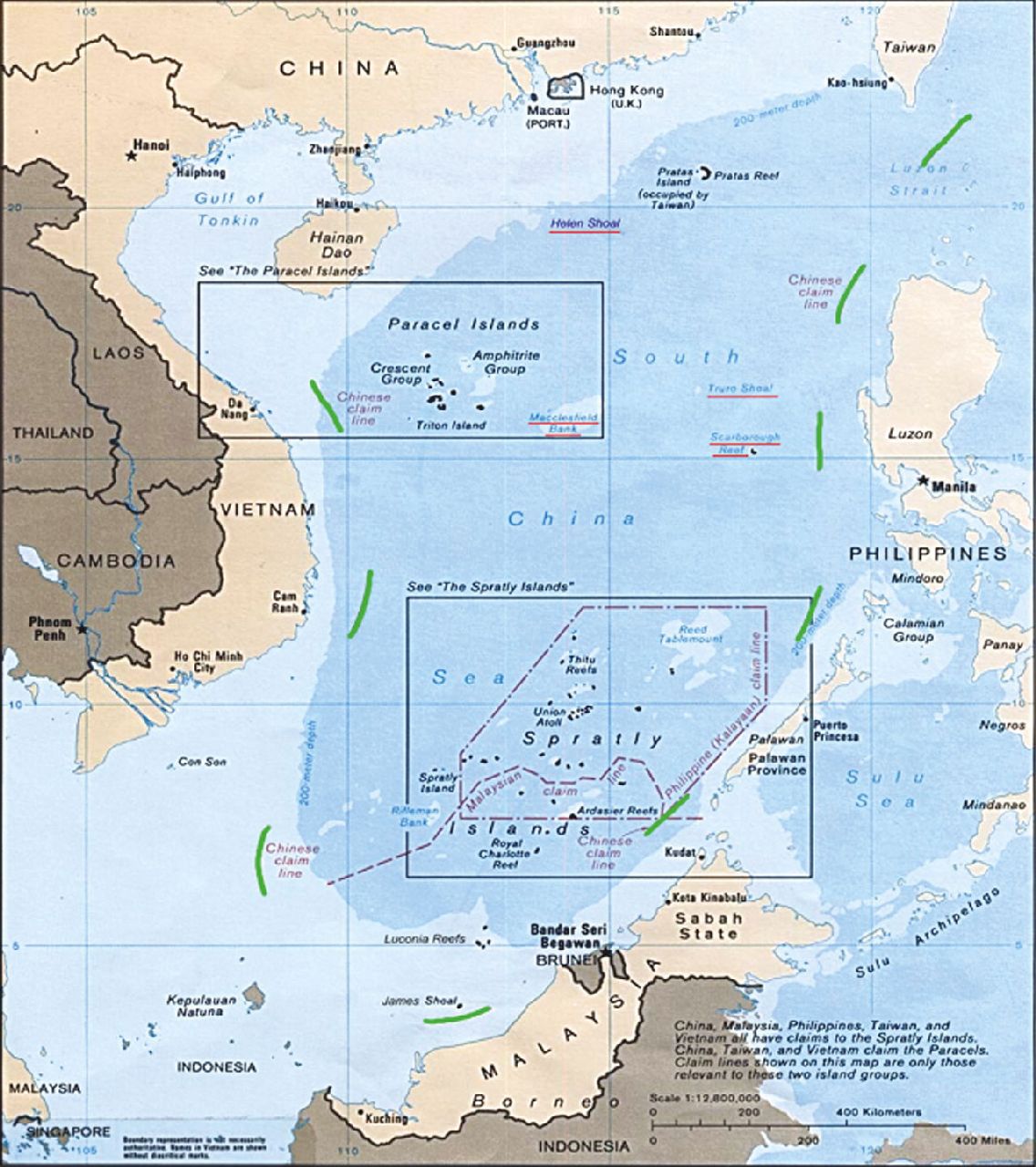

Perhaps the single most troubling diplomatic (and security) issue for Southeast Asians is the South China Sea (SCS) and China’s land reclamation of submerged “features” into full-blown islands—and islands that are increasingly militarized. There are two main clusters of islands—the Paracels (西沙) in the north and the Spratlys (南沙) in the south. Through its expansive “Nine Dash Line” (which appears like a giant tongue; see Figure 5.5) China claims the entirety of the SCS based on what it asserts are “historical rights” and previous precedent of the Republic of China’s assertion of these claims in 1947 (when it was an eleven-dash line).

Figure 5.5 China’s nine-dash-line claims in the South China Sea

Source: US Central Intelligence Agency, Asia Maps (1988), Courtesy of The University of Texas Perry-Castañeda Library

Figure 5.6 A Chinese Island (Subi Reef) in the South China Sea

Source: Digital Globe via Getty Images

China’s assertions are contested by six other claimants: Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and the Republic of China (Taiwan). In July 2016 an Arbitration Tribunal of the United Nations Law of the Sea in The Hague, Netherlands, ruled on the case brought by the Philippines that contested China’s asserted claims. The Tribunal ruled unanimously that there was no legal basis for China’s “historic rights” claims and nine-dash line. Faced with this unambiguous rebuff, the government of China refused to participate in the arbitration case and rejected outright its findings. Instead, Beijing issued its own White Paper reiterating its “unyielding position.”58 In addition to not recognizing other nations’ competing claims, China’s long-standing position has also been, contradictorily, that it is only willing to negotiate directly and bilaterally with the other contestants—and never in a multilateral setting or subjecting itself to any international mediation or imposed settlement. What China has been willing to do is to sign on to a Declaration of Conduct (DOC) in 2002, and more recently to enter into negotiations (near conclusion) on a revised and full Code of Conduct to govern states’ behavior under conditions of contested claims. The operative clauses of the 2012 DOC were:

Clause 4: The Parties concerned undertake to resolve their territorial and jurisdictional disputes by peaceful means, without resorting to the threat or use of force, through friendly consultations and negotiations by sovereign states directly concerned, in accordance with universally recognized principles of international law, including the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Clause 5: The Parties undertake to exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability, including, among others, refraining from action of inhabiting on the presently uninhabited islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features and to handle their differences in a constructive manner.59

Of course, one major problem with this sensible declaration is that China has demonstrably violated Clause 5 by reclaiming seven submerged shoals (“land features”) into full-blown islands, building structures and infrastructure on them, inhabiting them, and preparing them for an array of military equipment—from long-range radars to deep-water ports and submarine pens to 10,000-foot runways for bombers and fighters to land-based missile emplacements to housing for troops (see Figure 5.6). Beijing is also apparently making unreasonable demands of the other Southeast Asian states, which would, in effect, give China a veto over resource exploration or joint naval exercises with other countries (such as the United States). Thus there is still a fair amount of skepticism as to whether the revised Code of Conduct will be completed by its 2021 target date.60

To be sure, China is not the only claimant country to have inhabited or built military encampments on islands (Vietnam has, as well as Taiwan and the Philippines to a much lesser extent), but the PRC is the only one to have built artificial islands and militarized them to such an extent.61 As a whole, China’s claims and physical presence in the South China Sea are cancers on its overall image and relations with the region.62

People-to-people exchanges between China and Southeast Asian societies have expanded rather dramatically in recent years. They are embodied in the Action Plan of China-ASEAN Cultural Cooperation (2014–2018) and include a variety of activities.63 As part of its effort to get 250,000 Southeast Asian students studying Chinese, since 2009 China has sent more than 2,000 Chinese-language teachers and 15,319 volunteers to ASEAN countries, while the PRC’s China International Educational Foundation (formerly the Hanban) has also established 33 Confucius Institutes and 35 Confucius Classrooms, and provided 6,210 scholarships.64 The China Scholarship Council has also committed to providing more than 20,000 government scholarships for ASEAN students between 2018 and 2021.65 In an attempt to project its soft power, China has also established a number of Chinese Cultural Centers across the region (Figure 5.7), as well as a dedicated ASEAN-China Center in Beijing (Figure 5.8).

Figure 5.7 China Cultural Center in Singapore

Source: Author’s photo

Figure 5.8 ASEAN-China Center in Beijing

Source: Photo courtesy of John Holden

Chinese tourism in Southeast Asia is booming and is an increasingly important source of revenue for regional economies,66 growing fivefold over the past decade and now accounting for roughly one-fifth of all visitors to ASEAN.67 No doubt that the coronavirus pandemic will impact the flow of tourists in the short-term, but long-term growth trends remain robust. Tourists from outside ASEAN totaled 62.91 million in 2015, of whom 18.59 million came from China.68 By 2018, the number topped 20 million, according to China’s Ambassador to ASEAN, thus becoming the largest source of tourism to ASEAN countries.69 Ten million alone visited Thailand, four million visited Vietnam, three million visited Singapore, and two million each visited Indonesia and Malaysia in 2017, according to the McKinsey Global Institute.70 This is not insignificant given the dependency of these countries on tourism as a source of income (for example, tourism accounts for 28 percent of Cambodia’s GDP and more than 20 percent of Thailand’s, according to The Economist).71 McKinsey estimates that Chinese tourists spent on average per visit $3,000 in Singapore, $2,000 in Thailand, and $1,000 in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam.72 In 2015, 630,300 Chinese tourists visited the Philippines and spent $19 million in total.73 The number of flights each week from China to Southeast Asia, especially on budget airlines, is skyrocketing—and some regional airports are struggling to keep up with the volume. The number of Chinese tourists from interior so-called tier-two cities is also rapidly growing.74 Altogether there are 5,000 flights per week connecting Chinese and ASEAN cities.75 Most come on group package tours, but wealthy and mobile “Chuppies” (Chinese yuppies) are traveling in small groups or individually (Fig. 5.9).

Figure 5.9 Young Chinese tourists at Marina Bay Sands in Singapore

Source: Image Professionals GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo

Chinese tourists are drawn to the region by a variety of attractions. Shopping opportunities may be at the top of the list, but Southeast Asia’s relatively clean and less-populated beaches are also appealing. Direct flights connect multiple Chinese cities to Boracay and Cebu in the Philippines, Bali and Kuta in Indonesia, Langkawi in Malaysia, Phuket in Thailand, and other tropical destinations. Gambling is also a huge driver—especially to Cambodia, the Philippines, and Singapore. Chinese also have been buying property all across the region. Given the relatively inexpensive real estate, Thailand and the Philippines have become increasingly popular for Chinese who can afford it; Singapore, however, is too expensive for many Chinese to afford. Cheap currencies in several countries help to fuel the boom. And, of course, many Chinese like to visit relatives among the diaspora communities in Southeast Asia.

China-ASEAN educational exchanges are also booming. As of 2016, they totaled approximately 205,338 (81,210 ASEAN students in Chinese universities and 124,178 Chinese in ASEAN higher education institutions), according to official Chinese figures.76 An unknown number additionally study in high schools, notably in Singapore. The number of Southeast Asian students has now overtaken that of South Koreans as the largest on Chinese campuses. Table 5.4 provides the national breakdown of Southeast Asian students in China, with students from Thailand leading by a significant margin, followed by Indonesia, Vietnam, and Laos.

Table 5.4 Southeast Asian Students in Chinese Universities (2016)

| Country | Number |

| Brunei Darussalam | 70 |

| Cambodia | 2,250 |

| Indonesia | 14,714 |

| Laos | 9,907 |

| Malaysia | 6,880 |

| Myanmar | 5,662 |

| Philippines | 3,061 |

| Singapore | 4,983 |

| Thailand | 23,044 |

| Vietnam | 10,639 |

| Total | 81,210 |

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, China’s Foreign Affairs 2017.

The two sides marked 2016 as the China-ASEAN Year of Educational Exchange. For Southeast Asian students, Chinese universities and vocational schools offer a higher quality of education than can often be found at home (except in Singapore), and the cost of education is very inexpensive as compared with Western universities. Moreover, the Chinese government provides scholarships for many. In 2016, the government allocated $3.6 billion in 50,400 full scholarships covering tuition, accommodation, and living expenses, according to Zhou Dong, chairman of the China University and College Admission System (CUCAS).77 Southeast Asian graduate students can also often matriculate for their PhD degrees by only spending one year in residence in China and then are permitted to return to their home country, including the submission of the dissertation.78 Additionally, southern Chinese provinces—notably Fujian, Guangxi, and Yunnan—are providing their own separate sources of funding to Southeast Asian students.79 ASEAN students studying in Guangxi alone totaled nearly 10,000 in 2017.80 Another novel experiment is the branch campus of Xiamen University outside Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia—the first Chinese university to open a campus in the region.81 Chinese educational administrators are hoping to produce Southeast Asian students who “know China and are friendly to China” (知华友华).82

In the other direction, there has been a particular surge of Chinese students into Thai universities of late.83 In the 2017–2018 academic year, 8,455 Chinese students were enrolled in Thai universities—a doubling from the previous year.84 Thai universities are cost-effective for Chinese students (tuition averages just $3,700), a range of degrees and majors are offered, and Chinese language is easily used.

China also is involved in a multifaceted effort to shape perceptions throughout Southeast Asia. As it is doing across the world, China has embarked on a major effort to create a positive image of China, influence elites and publics in a pro-China direction, and undertake “external propaganda/publicity” (外宣) work.85

These efforts take a variety of forms. Some are legitimate, transparent, and normal public diplomacy. But others are covert, manipulative, and subversive. Much of the latter involves “united front work” (统战工作) that primarily targets the overseas ethnic Chinese communities. Some are in the gray zone between overt and covert—such as when PRC media reports are republished in Southeast Asian newspapers or social media (sometimes with attribution to Xinhua or other Chinese media, sometimes not). This is definitely the case in most Chinese-language media in Southeast Asia (Singapore’s Lianhe Zaobao is an independent exception), as is the case in many other countries. In Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Europe, the Chinese diaspora media are now almost entirely owned and controlled by PRC entities.86 Chinese films and television series are gaining increased viewership across the region—particularly in Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, and increasingly in Malaysia.87 But the PRC’s media penetration also reaches into English-language publications and social media, such as the Vientiane Times in Laos, Khmer Times and Cambodia Daily in Cambodia, The Star in Malaysia, Khaosod English in Thailand, and the Manila Bulletin in the Philippines, which all regularly run Xinhua articles and commentaries.88 Actually, this is not that unusual in developing countries. Across Africa and increasingly in Latin America, Xinhua provides low-cost or free content to local media—which is an important financial consideration for cash-strapped multimedia in less developed countries.89 In addition to Xinhua, the state news agency, other major Chinese media platforms also beam their transmissions directly to Southeast Asian (and other) audiences. The most notable of these at CGTN (China Global Television News) and China Radio International. In 2018 these two entities were amalgamated, along with CCTV-I (China Central Television International) and China National Radio into one mega state-run national media network called the Voice of China (since then Beijing has dropped the name, although the conglomerate continues).90 CCTV, CGTN, and Xinhua also all provide free content (video, digital, and print) to Cambodian National Television and the Cambodian New Agency. This is also the case with Malaysian and Thai TV.91

While a considerable amount is now known about China’s influence activities around the world and a significant number of studies have been published over the past few years,92 surprisingly little is known about China’s activities in Southeast Asia and virtually nothing has been published on the subject.93 This is something of a mystery. It is certainly not because Chinese influence activities do not exist, yet not much is known about their covert or disguised activities (outside of regional intelligence agencies). What is occurring are activities run by the Chinese Communist Party’s International Department (中共联络部 or CCP-ID),94 the CCP United Front Work Department (中共统战部 or UFWD),95 the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council,96 the Chinese People’s Institute for Friendship with Foreign Countries (中国人民对外友好协会 or CPIFFC),97 and the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs (中国外交学会 or CPIFA).98 While there is information available in China about these organs, they are not well known in Southeast Asia.

The CCP-ID is the most active of these organizations and is a Central Committee–level department.99 It carries out exchanges with a wide variety of political parties, parliamentarians, and retired politicians in all Southeast Asian countries. The vast majority are with Vietnam (as a fraternal communist party), but a review of their exchanges in 2018 and 2019 reveals a considerable number of exchanges with Thailand and Malaysia, followed by Indonesia.100 A survey of the UFWD’s website concerning overseas Chinese exchanges with Southeast Asia reveals a number of activities and delegations with Malaysia (the most), followed by Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines in 2018 and 2019.101 CPIFFC exchanges with Southeast Asia are few—only receiving visitors from Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand in 2018 and 2019.102 While CPIFA maintains exchanges with all parts of the globe, Southeast Asia does not seem to be a very high priority. During the period 2018–2019, for example, it received two former heads of state (Myanmar’s U Thein Sein and the Philippines’ Gloria Macapagal Arroyo), met with the Singaporean ambassador in Beijing, and carried out three annual bilateral forums (the China-Singapore Forum, China-Philippines Roundtable, and Seminar on China-Malaysia Relations).

Since 2009, when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs established its Office of Public Diplomacy, the Chinese government has also begun to invest much more heavily in traditional public diplomacy (公共外交) programs. Taking a leaf out of the United States’ public diplomacy playbook, the Chinese government brings significant numbers of influential “opinion shapers” and local officials to China on all-expenses-paid “soft power tours.” When I visited Yangon, Myanmar, I was told that the PRC has made a significant effort in this regard, after the government there abruptly terminated the Myitsone dam project in 2011—which totally surprised the Chinese concerning the extent of local opposition to the project (although the dam was symptomatic of broader and deeper Burmese concerns about Chinese penetration of their country). Thereafter, the PRC began bringing “hundreds” of Burmese to China on these tours in an attempt to co-opt them.103 Another source places the number between 1,000 and 2,000 since 2013.104 The PRC also runs a series of training courses in China for regional journalists and other professions. China’s 2014 Foreign Aid White Paper stated that from 2010 to 2012, China had trained over 5,000 officials and technicians.105

By far, the most systematic assessment of Chinese public diplomacy programs in Southeast Asia was a 2018 joint project of AidData (based at the College William and Mary in the United States), the China Power Project of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, and the Asia Society Policy Institute.106 The report describes the “targets” of public diplomacy to include “public officials, civil society or private sector leaders, journalists, academics, students, and other relevant socio-economic or political sub-groups.”107 The study thus cast its net widely—to include China—sponsored cultural events, Confucius Institutes, Chinese Cultural Centers, training programs, media dissemination, political parties exchanges, military exchanges, sister city programs, professional and scholarly exchange programs, friendship associations, student educational exchanges, and economic assistance (including humanitarian aid, infrastructure, debt relief, and budget support)—and it found that the Chinese government is active in all of these domains. In terms of results, it found that Beijing’s most effective tools are media penetration (especially among the Chinese diaspora), sister city and friendship association ties, Confucius Institutes, infrastructure building, development assistance and poverty alleviation projects, elite-to-elite exchanges, and professional training programs. In the case of Confucius Institutes, for example, as of 2018 there are sixteen in Thailand, seven in Indonesia, four in Malaysia, four in the Philippines, two in Cambodia, two in Laos, one in Singapore, and one in Vietnam.108 China’s national government agencies can be expected to continue to carry out, refine, and ramp up its public diplomacy efforts in all of these areas in Southeast Asia in the future. Chinese provincial organs—particularly in Fujian, Guangxi, and Yunnan—are also extremely active in their own exchanges with Southeast Asian countries.109

A more recent survey of China’s reputation and influence in the region is the “State of Southeast Asia 2019” annual survey undertaken by the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. When asked, “What country/regional organization has the most influence politically and strategically in Southeast Asia?,” 45.2 percent replied that China did (United States came second at 30.5 percent).110 Since ASEAN itself was included in the potential answer (20.8 percent), this is a little distorting. Nonetheless, China clearly is viewed as the most influential country in the region. When the same question was asked about economic influence, China scored even higher (73.3 percent). Yet China came dead last in “trust” rankings among Southeast Asians: Japan (65.9 percent), European Union (41.3 percent), United States (27.3 percent), India (21.7 percent), and China (19.6 percent). Conversely, in the “distrust” rankings, China came out on top (51.5 percent). So, clearly, influence and trust have an inverse correlation when it comes to China in Southeast Asia. The more China’s presence and influence grows, the less it seemingly is trusted.

The reason that the ISEAS survey is so useful and important is because it covers all ten ASEAN societies. Other global polling normally only includes two or three ASEAN countries. Take, for example, the Pew Global Attitudes Survey. In 2018, in its global poll evaluating views of China, it only included Indonesia and the Philippines. In Pew’s rather crude and oversimplified “favorability” ratings, an identical 53 percent viewed China favorably in each country.111 Another Pew survey in 2017 polled Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam. When asked if they viewed China’s rise as threatening, fully 80 percent of Vietnamese did, while 47 percent of Filipinos and 43 percent of Indonesians did.112

A primary target of China’s influence activities in Southeast Asia are the Chinese diaspora communities. For many years the PRC has done battle with Taiwan for the political loyalties of overseas Chinese, and since the 1980s Beijing has courted these communities for investments in China’s modernization drive. In more recent years, Beijing has based its appeals on global Chinese patriotism, admiration of China’s “great rejuvenation” (中国的大复兴), and Xi Jinping’s “Chinese Dream” (中国梦). Xi Jinping also announced a new “Grand Overseas Compatriots” (大侨务) policy intended to integrate a variety of overseas Chinese initiatives.113 He has also launched a new “three benefits” initiative: “to benefit China, to benefit host countries, and to benefit Chinese overseas.”114 The Chinese diaspora are, in particular, supposed to “act as a bridge to advance and implement China’s signature Belt and Road initiative,” according to the director of Peking University’s Center for the Study of Chinese Overseas.115

Despite Beijing’s outreach, ethnic Chinese have continued to live under suspicion in some Southeast Asia societies. By 2010 the number of overseas Chinese totaled 28.5 million.116 Of this figure, the composition by country is reflected in Table 5.5. Chinese in Southeast Asia represent approximately 70 percent of the total in the world. And many are extremely wealthy. According to Forbes, in 2019 overseas Chinese in the region accounted for three-quarters of the $369 billion in billionaire wealth.117 Overseas Chinese control a “bamboo network” of firms throughout the region.

Table 5.5 Number of Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, 2010

| Country | Overseas Chinese Population |

| Indonesia | 8,011,000 |

| Thailand | 7,513,000 |

| Malaysia | 6,541,000 |

| Singapore | 2,808,000 |

| Philippines | 1,243,000 |

| Myanmar | 1,054,000 |

| Vietnam | 990,000 |

| Laos | 176,000 |

| Cambodia | 147,000 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 50,000 |

| Total | 28,536,000 |

Source: 2011 Statistical Yearbook of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Council, Republic of China (Taiwan), 11.

Occasionally anti-Chinese violence flares up—as it did in Indonesia in 1998, 2015, and 2019; in Vietnam in 2014; and in Myanmar in 2015. While there have not been any public incidents of large-scale anti-Chinese riots in Malaysia since 1969, in 2015 there were two minor incidents that inflamed passions. Following these incidents, then Chinese Ambassador to Malaysia Huang Huikang gave a public speech, on the occasion of the annual September Moon Festival, in which he stated: “We will not stand idly by as others violate the national interests of China, or infringe upon the legal rights of Chinese citizens and companies.”118 This speech attracted much attention in Malaysia, Singapore, and throughout Southeast Asia. But then, a week later, Ambassador Huang made an even more provocative statement in a speech to a Maritime Silk Road forum, in which he asserted: “I would like to stress once more, overseas huaqiao (华侨) and huaren (华人), no matter where you go, no matter how many generations you are, China is forever [emphasis added] your warm maternal home (娘家).”119 This statement was widely interpreted in regional media as a significant qualification of China’s Nationality Law and raised concerns that China was again asserting some kind of legal provenance over Chinese diaspora abroad. The Nationality Law of 1980 reaffirmed that China does not extend or recognize dual nationality (Article IV), while Article V categorically clarifies that “any person born abroad whose parents are Chinese nationals, or one of whose parents is a Chinese national, has Chinese nationality. But a person whose parents are Chinese nationals and have settled abroad, or one of the parents who is a Chinese national and settled abroad and has acquired foreign nationality on birth, does not have Chinese nationality.”120

For those Chinese who have emigrated from the PRC to Southeast Asian societies, there can be significant problems of social adjustment and conflicted identities. One study focusing on recent arrivals in Singapore conducted by Liu Hong, a well-known professor and former Dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, found that the new immigrants still identify their patriotism much more with the PRC than with their new native countries, they tend to socialize together and not integrate into local diaspora communities, are not very cosmopolitan, and have a hard time adjusting to local customs, rules, and laws. Many also have difficulties adjusting to multicultural societies. On the other hand, Professor Liu’s study found the opposite problem with long-resident overseas Chinese. Many had been “de-Sinified” (去中国化), having been away from mainland China for so long, and thus were in need of “re-Sinification” (再华化) in order to re-establish their “Chineseness” (华人性) and cultural connections to China.121

Thus, the overseas Chinese issue has remained a complex and sensitive one in many Southeast Asian countries since the establishment of the PRC. As one of the world’s leading experts on overseas Chinese, Leo Suryadinata of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore, observed in his recent definitive study of the subject: “Beijing has attempted to blur the distinction between Chinese citizens and foreign citizens of Chinese descent, as reflected in various recent external and internal events involving the Chinese overseas. China has also begun to show its intention to protect not only Chinese nationals overseas, but also those Chinese overseas who have become foreign nationals. It seems that Beijing has forgotten its earlier policy of encouraging the Chinese overseas to integrate into local society and respect the rules and regulations of their adopted countries.”122

The United Front Work Department (统战部) is clearly the most important institutional actor vis-à-vis overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. Following a reorganization and bureaucratic upgrading of the department in 2018, the State Council’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission (侨务委员会) was moved under the CCP UFWD, and a separate Overseas Chinese Affairs Bureau (the UFWD’s ninth bureau) was established to coordinate work worldwide.123 The China Council for the Promotion of Peaceful National Reunification, a united front organization that is under State Council auspices (rather than the UFWD),124 is also an important player and has long had branches and affiliated organizations in several Southeast Asian countries (Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand).125 In addition to carrying out activities in the region, the council also convenes a global conference that brings delegates from all over the world to Beijing (during which presumably they receive instructions for their annual work).126 This meeting usually coincides with the annual united front Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress (CPPCC) every March.

In business circles, China also has established and operates Chinese Chambers of Commerce (CCOC or 中国商会) in all ASEAN countries.127 These are not merely targeted at overseas Chinese business circles, but toward the commercial sector in those countries more generally. The CCOC in Myanmar was established in 1996; Vietnam in 2001; Brunei, Indonesia, and Laos in 2005; Thailand in 2006; the Philippines in 2007; and Cambodia in 2009. The CCOC in Malaysia dates its origins to 1904 and the one in Singapore to 1970. These organizations undertake a wide range of national and community activities: trade and investment promotion, local philanthropy and charity work, government liaison, commemorative cultural events (e.g., Moon Festival, Lunar New Year), contributing to disaster relief, and staging exhibitions.128

Although generally dormant following the persecution of the Hoa population in Vietnam in the years 1975–1978, the sensitivities surrounding overseas Chinese have occasionally flared up in Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Vietnam. Since China introduced its Patriotic Education Campaign in the early 1990s, this has been extended to overseas diaspora communities through the UFWD and Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission. The majority of Chinese-language newspapers and media abroad are now owned and controlled by united front affiliates. The increased penetration of overseas Chinese communities by the CCP united front organs (including appointing prominent members of overseas Chinese communities as deputies of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress) has raised concerns,129 and is an increasing concern and priority for a number of intelligence agencies in the region.

Chinese citizens overseas have also become much more active in public demonstrations that promote the PRC and denounce groups that criticize China. Such demonstrations are often orchestrated and coordinated with local Chinese embassies or consulates. Chinese officials abroad have also become more assertive in speaking out. Thus, after many years of relative quiescence, it is apparent that China has again begun to be more proactive concerning overseas Chinese.

Although traditional diplomacy and people-to-people exchanges are important elements in China’s regional toolbox, trade and investment are far and away the most important. They dominate China’s regional footprint in Southeast Asia and both dimensions are growing rapidly. Chinese companies are all over the region, with more than 6,500 registered in Singapore alone.130 However, getting fully accurate and consistent statistics on China’s regional trade, and particularly investment, is not easy.

China has been ASEAN’s largest trading partner since 2009, accounting for $587.87 billion in 2018 (excluding trade via Hong Kong), according to data from the China’s Ministry of Commerce.131 This represents a nearly 900 percent increase since 2001 (see Figure 5.10). China’s trade with Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam have grown the fastest: 24 percent, 37 percent, 33 percent, and 30 percent on average, from 2001 to 2014.132 By mid-2019 ASEAN had, in fact, overtaken the United States as China’s second largest trading partner.133

Figure 5.10 China-ASEAN trade, 1996–2018

Source: ASEAN Focus; ASEAN Secretariat

The trade relationship received a big boost in 2010, when the China–ASEAN Free Trade Area (CAFTA) came into effect. CAFTA includes a combined population of 1.9 billion and $4.5 trillion in trade volume. Under CAFTA, China and ASEAN agreed to zero tariffs on 90 percent of each other’s goods. China and ASEAN “upgraded” CAFTA in 2018 and both sides set the goal of $1 trillion in total trade by 2020 (while having grown rapidly this was an overly ambitious target). By 2018, according to the CEIC database,134 China’s trade with countries in the region was: Vietnam ($106 bn.), Singapore ($100.2 bn.), Thailand ($80.2 bn.), Malaysia ($77.7 bn.), Indonesia ($72.6 bn.), the Philippines ($30 bn.), Myanmar ($11.7 bn.), Cambodia ($7.7 bn.), Laos ($3.47 bn.), and Brunei ($1.8 bn.).135 However, among its ASEAN trading partners, in 2018 all countries except Laos and Singapore ran a trade deficit with China.136 Collectively, ASEAN ran a $90.5 billion deficit in that year, with Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia being by far the largest.137 The rate of growth of imports from China in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand from 2013 to 2018 has been particularly dramatic (and their trade deficits have consequently ballooned).

Southeast Asian countries are also increasingly settling commercial transactions in Chinese renminbi. Currency exchange swaps are already in practice for the Indonesian rupiah, Malaysian ringgit, Philippines peso, Singaporean dollar, Thai baht, and Vietnamese dong—while China and ASEAN have agreed to moving further toward “de-dollarization” by expanding local currency settlement. Also, with the United States’ withdrawal from TPP, ASEAN and China are pushing ahead with the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) initiative, essentially an Asian regionwide free trade area between the ten members of ASEAN and six other regional countries.

While the joint aspiration of achieving $1 trillion in China-ASEAN trade by 2020 fell short, there is no disputing the rapid and dramatic upward trajectory in two-way trade. And with trade comes interconnectivity (human and digital). The interconnectivity is further fueled by investment. China and ASEAN are quickly and increasingly becoming deeply integrated economically. This trend is only likely to grow and accelerate.

Chinese investment into ASEAN has also been spiking upward, reaching $13.7 billion in 2017 before sliding back to $10.1 billion in 2018 (see Figure 5.11). Establishing an accurate estimate for the total FDI stock of China in ASEAN is not easy, but by combining official Chinese and ASEAN statistical sources a reasonable estimate is $84.7 billion by the end of 2018.138 While this overall cumulative total is not that much (especially when compared with that of the United States or EU), China’s annualized FDI inflows to Southeast Asia have been trending upward in recent years. It more than quadrupled between 2010 and 2018. China is already the largest total foreign investor in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.139 In 2017, China accounted for 40 percent of Singapore’s inbound FDI, 16 percent of Indonesia’s, 14 percent of Malaysia’s, and 30 percent of the other seven ASEAN members.140 Over time from 2003 to 2014, according to one study, Singapore was the largest recipient of Chinese FDI (37 percent), followed by Indonesia (15 percent), Laos (10 percent), Thailand and Myanmar (9 percent), Cambodia (8 percent), Vietnam (5 percent), Malaysia (4 percent), Philippines (3 percent), and Brunei negligible.141

Figure 5.11 Chinese investment in ASEAN, 1996–2018

Source: ASEAN Focus; Financial Times

Despite the sharp increase of Chinese investment flowing into the region since 2010, this must be kept in comparative perspective. In 2017 a total of $154.7 billion was invested in the region from abroad according to ASEAN statistics.142 The United States came first ($24.9 bn.), followed by Japan ($16.2 bn.), the European Union ($15 bn.), and China ($13.7 bn.).143

Chinese investment is expected to grow severalfold in coming years (DBS Bank in Singapore estimates it will reach $30 billion by 2030),144 stimulated in particular by China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road initiative (half of One Belt, One Road, a.k.a. the Belt and Road Initiative).145

The Maritime Silk Road is a sprawling set of projects spanning Southeast Asia to Southeastern Europe. In Southeast Asia, it includes a number of separate country “corridors” and economic cooperation zones—such as the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Corridor, China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor, Nanning-Singapore Economic Corridor, Guangxi Beibu-Brunei Economic Corridor, Pan-Beibu Gulf Economic Cooperation Zone, Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Zone, and China-Vietnam Two Corridor and One Circle Cooperation Zone. Some of the more important projects include:146

• an 1,800-kilometer highway from Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province, to Bangkok;

• three separate high-speed rail lines from Kunming down into Myanmar, Vietnam, and Laos—the latter connecting to Thailand, Malaysia, and ultimately Singapore;

• a 150-kilometer high-speed rail line between Jakarta and Bandung in Indonesia;

• an East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) in Malaysia, with a cross-peninsula line connecting the Klang and Kuantan ports with points north along the east coast of the country up to the Thai border;

• major port building and upgrading at Klang, Kuantan, Kuala Linggi, Malacca, and Penang in Malaysia; Kyaukphyu and Maday Island in Myanmar; Tanjung Sauh, Jambi, and Kendal in Indonesia; Kompot and Sihanoukville in Cambodia; and Maura in Brunei;

• a 479-mile oil and gas pipeline from Yunnan through Myanmar to the Bay of Bengal;

• major bridge projects in Penang, Malaysia; southern Leyte to Surigao City, Luzon-Samar, and Panay-Guimaras-Negros in the Philippines; and across the Mekong River between Laos and Thailand;

• a new airport in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and expansion of the airport in Luang Prabang, Laos;

• an expressway from Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville, Cambodia;

• metro expansion in Hanoi, Vietnam;

• four hydropower dams in Laos, two dams and two hydropower plants in Cambodia, one plant in Myanmar, two in Indonesia, and one in Vietnam.

These and many other projects are already underway, with more on the drawing board or in negotiation stage. In 2019, BRI projects and investments showed a sharp rise to $11 billion just in the first half of the year.147 As of 2019, one report indicates that among BRI projects either “at the stage of planning, feasibility study, tender, or currently under construction,” Indonesia currently leads the way ($93 bn.), followed by Vietnam ($70 bn.) and Malaysia ($34 bn.).148 Let us examine one national case that illustrates both the extent and the problems with China’s BRI initiative in Southeast Asia: Malaysia.

Overall, Malaysia has been a particular beneficiary of OBOR/BRI, with many major projects launched during the rule of Prime Minister Najib Razak (2009–2018). This included projects such as Melaka Gateway ($10 billion), Bandar Malaysia ($8 billion), Kuala Linggi International Port ($2.92 billion), Robotic Future City in Johor ($3.46 billion), Kuantan industrial park and port expansion ($900 million), Samalaju Industrial Park and Steel Complex ($3 billion), Penang waterfront land reclamation project ($540 million), Pahang Green Technology Park ($740 million), Forest City mixed-development project ($100 billion), and the East Coast Rail Link ($16 billion).149 I discussed the Forest City and Melaka Gateway projects in the Preface.

Taken together the investment footprint in Malaysia is the largest of all BRI recipient countries in Southeast Asia. So sweeping is the footprint of BRI projects in the country, that one Malaysian academic I met with described his country as “ground zero for OBOR.”150 Another Malaysian Foreign Ministry official echoed this: “We are the indispensable country for BRI, and the Chinese know this.”151 Malaysia and China clearly had big plans for commercial cooperation. Between 2010 and 2016, China invested $35.6 billion in construction projects in Malaysia, according to the Malaysian Department of Statistics.152

Despite this optimistic overall atmosphere, several of the ambitious projects began to hit hurdles in 2017—both financial and political. In May of that year, Chinese funders withdrew their financing that was to cover 60 percent of the Bandar Malaysia project.153 More significantly, a major perceptual shift was taking place across the country. Malaysians feared the country was being overrun by Chinese investment and that the terms of indebtedness and ceding of sovereign access to China would be far too great a burden for the country to bear.154

One notable Malaysian who shared and tapped into these sentiments was then ninety-two-year-old former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad—who decided to come out of retirement and challenge Najib in the 2018 elections. Najib’s political party, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), used to be Mahathir’s too and it had never lost a national election. But Mahathir achieved the unthinkable and defeated Najib at the polls. His skepticism of China’s financial footprint in the country was a key plank of his election platform. Chinese had been on a buying spree beyond BRI infrastructure, including huge rubber and palm oil plantations, beachfront properties and hotels, and industrial parks—and it resonated with the electorate.155 In January 2017, in a public speech, Mahathir railed against “foreigners being given large tracts of land to build property that will be occupied by them. . . . Singapore was our territory, but not now. If we think a little bit, this is happening again. Our heritage is being sold, our grandchildren won’t have anything in the future.”156 In 2019, Mahathir further reflected in an interview on American public television: “Everything was imported, mostly from China—workers were from China, materials were from China, and payments for the contracts were made in China. That means that Malaysia doesn’t get any benefit at all. The whole thing was done in a hurry by the previous government without due regard for the interests of Malaysia.”157