Let us define the basic terms nutrition experts use in planning health-promoting diets. What do we mean when we talk about carbohydrate, protein, and fat? What are they for, and how much (or how little) of each should we be getting each day?

Good nutrition means getting these nutrients, along with fiber, vitamins, and minerals, not only in the right amounts, but also in the right form. This chapter will help you understand the basics of the macronutrients (carbohydrate, protein, and fat) and fiber—why we need them, and what the most healthful choices are.

It is remarkably easy to get enough protein. A variety of grains, legumes, and vegetables can provide all of the essential amino acids our bodies require.

Carbohydrate is the main source of energy in a health-supporting diet. It is the primary fuel source for the brain and muscles and helps maintain nervous system function. Normally, your body stores a bit of carbohydrate in your muscles and liver as glycogen, which acts as a reserve energy source. Liver glycogen maintains blood glucose levels, but it is soon depleted if no carbohydrate is consumed. When that happens, your body can make carbohydrate from amino acids that are drawn from your muscles, but that means that your muscle mass will dwindle.

There are two types of carbohydrate: simple and complex. The term simple carbohydrate refers to sugars found in fruits or in concentrated forms, such as table sugar.

Complex carbohydrate, or starch, is composed of many sugar molecules joined together. The following are some common foods that are rich in complex carbohydrate:

Generally speaking, you will want to favor foods rich in complex carbohydrate. For most people, 55–75 percent of daily calories should come from carbohydrate.

Fiber is only found in plant foods. This is why vegetarians, particularly vegans, often have a high fiber intake. Fiber provides us with many benefits, including reduced cancer risk, as we saw in chapter 2. Fiber intake is one of the reasons vegetarians have significantly lower rates of cancer, heart disease, and diabetes and are usually slimmer than other people. Fiber helps you to fill up so that you don’t “fill out.”

The two types of fiber are insoluble and soluble. It is important to have both insoluble and soluble fiber in your diet. Most foods contain a mixture of both fibers, and the two types are not usually differentiated on food labels.

Insoluble fiber does not readily dissolve in water. It increases fecal bulk and decreases intestinal transit time. All plants, especially vegetables, wheat, wheat bran, rye, and rice, are rich in insoluble fiber.

Soluble fiber dissolves or swells when it is put into water and is readily metabolized by intestinal bacteria. It has been shown to help lower cholesterol levels and slow down gastric emptying time (thus keeping you full longer). Beans, fruits, and oats are especially good sources of soluble fiber. Other examples of soluble fiber include guar gum and locust bean gum—these are commonly used as thickeners and found in salad dressings and jams.

Most health authorities recommended fiber intake in the range of 25–35 grams per day as a minimal goal, and, optimally, your goal should be about 40 grams. The average American eats 14–15 grams a day, and vegetarians get two to three times that amount. Increase your fiber intake slowly, and increase water intake as well. Here is the fiber content of some common foods:

Protein is needed to build and repair muscles, bone, skin, and blood; regulate hormones and enzymes; and help fight infection and heal wounds. It is also an integral part of genes and chromosomes.

The building blocks of protein are called amino acids. The body can synthesize some amino acids; others must be ingested from food. Of the twenty or so different amino acids in the food we eat, our bodies can make eleven. The nine remaining amino acids are called essential amino acids—that is, the body cannot produce them, and they must be obtained from the diet.

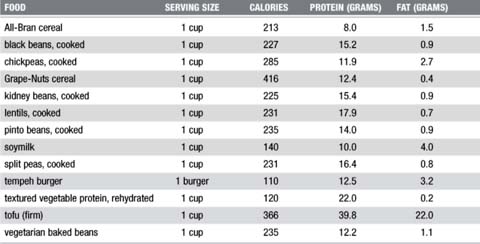

TABLE 22 Higher-protein plant foods

It is remarkably easy to get enough protein. A variety of grains, legumes, and vegetables can provide all of the essential amino acids our bodies require. It was once thought that to get adequate protein various plant foods had to be consumed together, a practice known as protein combining or protein complementing. However, researchers have found that intentional combining is not necessary. As long as the diet contains a variety of grains, legumes, and vegetables, protein needs are easily met.

Approximately 10–15 percent of daily calories should come from protein. Protein needs depend on body weight, and requirements increase with activity level and body stress (such as tissue repair or medical treatments). All foods except pure fats, sugars, and alcohol contain protein. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for protein for the average sedentary adult is only 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight, with protein needs increasing only slightly with more activity. To find out your average individual need, simply perform the following calculation: body weight (in pounds) x 0.36 = recommended protein intake (in grams).

Here is an example: A person who weighs 150 pounds needs 54 grams of protein per day. What does 54 grams of protein look like on a full day’s menu?

Breakfast: 1 bowl of bran cereal with raisins and 1 cup of soymilk |

12 grams |

Lunch: 1 veggie burger on a whole wheat bun |

20 grams |

Dinner: 1 cup of pasta with 1 cup of assorted vegetables and beans |

22 grams |

Protein Total for the Day |

54 grams |

The most protein-rich plant foods are listed in table 22. Legumes (beans, peas, and lentils) are especially rich in many healthful nutrients and supply a substantial amount of protein. Most varieties of legumes are about 25 percent protein and yield approximately 15 grams of protein per cup. But don’t think that beans have a patent on protein. Wheat noodles contain substantial amounts; some varieties have about 10 grams of protein in every 2 ounces of dried pasta, and that’s before you figure in any toppings.

Fat is the most concentrated source of calories. Any sort of fat—chicken fat, fish fat, beef fat, or vegetable oil—has 9 calories per gram, more than twice the calorie content of carbohydrate or protein. Most health authorities recommend that fat intake not exceed 30 percent of our calories. This means that a person consuming 2,000 calories per day should have less than 60 grams of fat per day.

However, research has shown that the lower your fat intake, the better your chances of warding off heart disease and cancer and keeping your waistline slim. A healthier goal is to limit fat to about 25–35 grams per day.

Fats are made up of a combination of fatty acids, which can be monounsaturated, polyunsaturated, or saturated. All fats contain some of each of these three, but health authorities have long recommended minimizing saturated fats because of their tendency to raise cholesterol levels. Animal products are generally very high in saturated fatty acids, whereas vegetable oils are generally much lower in this type of fat. There are a few exceptions: coconut oil, palm oil, and palm kernel oil are quite high in saturated fat.

Fat is necessary for the structure and maintenance of cells and hormones, healthy skin and hair, and the metabolism of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). As long as we consume enough calories, we can synthesize fat from surplus protein and carbohydrates. However, there are two essential fatty acids that we need to obtain from our diet. They are alpha-linolenic acid (an omega-3 fatty acid) and linoleic acid (an omega-6 fatty acid). Both are important in the normal functioning of all tissues of the body. Deficiencies are responsible for a host of symptoms and disorders, including abnormalities in the liver and kidney, changes in the blood, reduced growth rates, decreased immune function, and skin changes, such as dryness and scaliness. Adequate intake of the essential fatty acids results in numerous health benefits, including reduced incidence of heart disease and stroke and relief from the symptoms associated with ulcerative colitis, menstrual pain, and joint pain.

Most people consume too many omega-6 fatty acids and too few omega-3 fatty acids. It’s important to maintain a balance of these two. Omega-6 fatty acids are present in higher concentrations in many foods, whereas omega-3 fatty acids are not as widespread. Beans, vegetables, fruits, and whole grains do contain omega-3 fatty acids, but the most concentrated plant sources include canola oil, flaxseeds, wheat germ, soybeans, and walnuts.