The Regulative and the Theoretical

2.1 A third distinction

Two distinctions drawn in normative epistemology have now been outlined: one between the things we are seeking to account for (rationality versus knowledge); and another between the different types of epistemic theory trying to account for these (internalism versus externalism). This chapter concerns a third distinction – between the regulative and the theoretical. This distinction is well known, at least at a surface level; yet its significance is still not fully appreciated. It is powerfully similar to a distinction drawn in ethics. We uncover this third distinction via a consideration of the arguments levelled by internalists (deontologists) against externalists (consequentialists) and vice versa. Of course, the protagonists in these debates see them as being directed towards establishing which of internalism or externalism is the true theory of knowledge or rationality; however, for us, uncovering these arguments will be in the service of another end.

2.2 Why internalists and deontologists draw this third distinction: The epistemic poverty objection

The deontic conception of internalism (henceforth and throughout: just ‘internalism’) involves the idea of cognitive accessibility, of epistemic deontology, and of these being connected via what, in Chapter 6, I call a deontic leeway entailment – here, ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ (OIC). These things may be used to create a problem for internalism. I may have done all I can epistemically, dutifully discharging my intellectual obligations to the limit of my abilities. Still, I may be desperately far removed from either the truth or an objectively truth-conducive basis for my belief. This was entitled the ‘epistemic poverty objection’ by (BonJour 2003: 176); with a classic source being Alston (1985). Alston gives examples of dutiful but helplessly flawed cognizers, examples typical of many in the externalist literature: a tribesman may have been brought up to accept the traditions of his tribe as authoritative, and never have seen anything to call these traditions (of inquiry, etc.) into question. A person may be intellectually honest and diligent, but just rather dim; or not dim especially, but highly impressionable. A person may lack an education, being vulnerable to all kinds of unfounded hearsay and superstition as a result. In general, one may have discharged one’s epistemic duties as responsibly as one is able, but still (blamelessly) be holding one’s beliefs on profoundly inadequate grounds. Thus, it is argued, the deontic conception of internalism is an inadequate epistemic axiology.

This objection originated as an argument against ethical deontology. In both ethics and epistemology, it has a stock response. This is to draw a distinction between objective and subjective duty.1 One is culpable, blameworthy, irresponsible, should one fail to discharge one’s subjective duty (doing what one has reason to believe will bring about the right); one is not blameworthy or irresponsible merely in virtue of failing to discharge one’s objective duty (actually maximizing the good) – which failure may be quite out of one’s hands. Owens (2000) notes this distinction in Sidgwick (cf. 1907: 413). Plantinga (1993) credits his version of this distinction to Aquinas; though a more immediate source might well be Chisholm (1957), who draws the same distinction using the terms ‘practical’ for subjective and ‘absolute’ for objective – himself crediting Richard Price. To escape the epistemic poverty objection, deontic, oughts-based justification must be restricted in its application to the subjective, practical realm. There is another objective, absolute sense of being justified for which the discharge of duty, the fulfilment of obligations, be we ever so diligent, is not guaranteed to satisfy. Consider, in light of this, a claim such as the following:

I shall assume that only right epistemic rules make a difference to genuine justifiedness. This point should be equally acceptable to both internalism and externalism. (Goldman 2009: 5–6, emphasis in original)

This point will be ‘equally acceptable to both internalism and externalism’ only should it be read by each under a different interpretation of ‘right epistemic rule’. For the internalist, this means subjectively right; for the externalist, objectively right.2 Argument at cross purposes beckons if we do not keep this in mind.

2.3 Why externalists and consequentialists draw this third distinction: The doxastic decision procedure objection

In ethics, there are a set of stock objections to consequentialist theories (e.g. act utilitarianism) and in turn a stock response to this set of objections (to draw the regulative–theoretical distinction). The objection and associated response carried over into epistemology. Brink (1986) called this family of objections in ethics generally the objection from the ‘personal point of view’. There are several such objections that do not concern us, but a version that does – found in each of Bales (1971), Brink (1986) and Smith (1988) – is as follows: working through the act-utilitarian (or other) consequences of even a simple choice of action is likely to be a highly involved matter. Bring other choices into the equation, factor in a diachronic time-scale, incorporate a need to take on new information in real time, and the matter becomes massively more involved. The process of calculating these consequences – to even a modest level of surety – takes time. Frequently, for the agent to embark on the process of calculating the consequences of a course of action will itself be to choose one way or other how to act (and often, to choose wrongly).3

This objection to consequentialism in ethics carried over directly into epistemology, where it was levelled by internalists against externalism. One traditional ambition of epistemology is to offer the agent ‘rules for the direction of the mind’; that is (whether actually rules-based or not), an epistemology that can offer guidance in cases where the agent is undecided and facing a doxastic choice. But for an account to be able to offer me practical help in cases of judgement under uncertainty, it is necessary for it to restrict itself to resources – a justificatory ground – that may be available to me in that epistemic dilemma, with those limited resources (processing/capacity limitations, time constraints, restricted knowledge base, etc.). Decision-making requires me to have access to my justifiers. Goldman (1980) referred to this as the aspiration that epistemology should offer the agent, facing a decision, a ‘doxastic decision procedure’ (DDP) – where this latter is a dummy for whatever set of rules for guidance (whether actually rules-based or not) the epistemologist’s theory finally divulges. But the objective, truth-directed nature of an externalist theory in epistemology is not guaranteed to give the undecided agent access to any such DDP. In the language of the psychologists, such theories may yield accounts of justified cognition that are computationally intractable – hence unusable for the purpose of guidance under uncertainty. So, relative to this ambition, externalism is a failure.

2.3.1 Negative response: What should we do in the meantime?

Goldman (1980) made a tu quoque response to the DDP objection – namely, that it applies no less to many varieties of internalism.

Whatever the internalistically right DDP is supposed to be, we could not rely on it falling to us from heaven. We should probably have to work to get it. The same questions, then, arise: how should we form our doxastic attitudes in the meantime? and which DDP should we use in searching for the internalistically right DDP? These worries do not create a special presumption against externalism, since they are of equal significance for internalism. (Goldman 1980: 46)

This point is well taken as far as it goes: many supposedly internalist theories are indeed too complex and defeasible for an agent to have access to their criterion of epistemic success. Indeed, this may serve as a criticism of certain (e.g. ‘mentalist’,4 or highly complex introspectionist–foundationalist) conceptions of internalism – this being the ‘Forth bridge’ point, articulated in Section 1.2 of the previous chapter. But we saw in that chapter that not all species of internalism are like this. With a deontic conception of internalism allied to a commitment to OIC, one may start with the powers of the agent and delimit one’s account of their epistemic requirements accordingly. This ‘bounded’ notion of epistemic justification leads to accounts of epistemic justification that are not vulnerable to the DDP objection. A paradigm of such an account in normative epistemology would be Richard Foley’s work (e.g. Foley 1993). In the economics and psychology literature, this becomes Herbert Simon’s notion of ‘bounded rationality’. Some (actually many) of these bounds are cultural, and in the anthropology and cultural psychology literatures, this involves the Vygotskian notion of a zone of proximal development (Lockie 2016a,b), with Elqayam (2011, 2012) dubbing this a notion of ‘grounded rationality’.

For the deontological internalist who takes OIC seriously, epistemology cannot be the project of achieving some absolute justification, whether an objective relation to the facts or to the world; or an optimally (impossibly) coherent or foundationalist system of beliefs – some inaccessible and superlative ‘DDP’. It is rather a thinner project, one which starts with the powers of the agent, her actual, limited, time-constrained cognitive resources, then providing an account of how she should move forward from these – and these alone. For such an internalist, the project of accounting for justification is to answer the regulative question not with some enormously complex and inaccessible theory, some ‘DDP’ that doesn’t typically yield a decision in the time required; but to take the bounded agent, with her powers, her perspective, and ask precisely: given only this, what should she do ‘in the meantime’?

2.3.2 Positive response: The regulative versus theoretical distinction

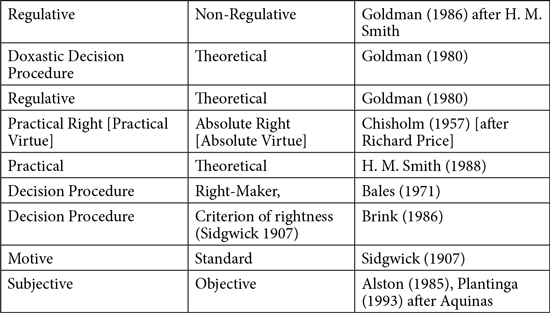

The classic response by externalists and consequentialists to the DDP objection again involves making a dichotomous distinction as to the aims of an epistemic (/ethical) theory. The terminology of this distinction varies, though in ways that carry some useful semantic pointers as to the underlying differences between its two terms. In what follows, I use the terms regulative and theoretical. A list of cognate terms, with sources, is provided in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Terms used to draw the regulative–theoretical distinction

Source: Lockie (2014c) – adapted.

Externalists/consequentialists are criticized by their opponents for offering epistemic (/ethical) theories that may not be usable by the agent facing a decision to regulate thought. Their response is simply to note that this regulative, action-guiding ambition is not a desideratum of their kind of account. Rather, in the case of epistemology, the externalist seeks only to specify when a belief, a belief-making process or a course of cognitive conduct is justified objectively (say, in terms of truth maximization or error avoidance).5

2.4 Two motivations but one distinction

Each of internalism and externalism levels a standard objection against the other. Each must draw a distinction to escape the objection to their position. Each draws this distinction in terms of the desiderata of their theory – and what instead is acknowledged to be no part of its aim. And each does this by explicitly borrowing both objection and distinction from an already developed body of argument in ethics.

Externalist theories identify a very central aspect of what one expects of an epistemic theory: their different, proprietary ways of marking a connection with the truth, their objectivity. Minimally, this connection is represented by the idea of truth as a necessary condition on knowledge; though, of course, conventional externalist theories tend to go far beyond this in their different accounts of warrant. These wide variations of detail do not obscure the point: that one cannot mark the objectivity, factuality, that such accounts base their epistemic success-term upon – their emphasis on what is actually truth conducive (or error avoiding) in cognition – without losing any necessary connection with accessibility. Making epistemic normativity essentially objective means that it can be at best only contingently accessible. For the world is as it is, and we are as we are, and as fallible beings with widely differing epistemic resources, our ability to achieve a given objective epistemic status will be tenuous and uncertain. The potential inaccessibility characteristic of externalist theories is then not a definitional primitive, but a derived consequence of their objectivity, however this latter be construed, even if it be no more than the attainment of truth, much less if it be something more.

Internalist theories also identify a very central aspect of what one expects of an epistemic theory: their different, proprietary ways of marking a connection with the subject, their help to the subject as a guide, their directiveness – of the subject’s cognitive conduct, of thought. Internalist theories’ restrictions on only accepting a justificatory ground that may be accessible to the agent is also then best seen not as a definitional primitive, being rather derived from the desideratum of satisfying this regulative, directive aim: of satisfying it not accidentally, but essentially. To be necessarily capable of directing cognitive conduct, a theory must be accessible, it must not go beyond the resources of the epistemic agent: remaining within the compass of his intellectual abilities, or at least his ‘zone of proximal development’ therefrom (Vygotsky 1978; Plato 1992: 197c–d; Lockie 2016a,b). It is for this reason that a widely canvassed criticism of those deontic conceptions of rationality which strongly embrace OIC is not entirely well-taken – namely, that said approaches fail to sufficiently respect the distinction between rationality and epistemic justification. Any notion of rationality has to respect the fact that it applies to human beings (is bounded by human limits): that it is not ‘God’s Rationality’. God’s Rationality is simply truth – inaccessible truth. It cannot be that epistemic rationality is unbounded, idealized, reified. It is not then easy to motivate a distinction between deontic, perspectivist, bounded justification and a more-idealized, reified, absolutist notion of epistemic rationality. Granted, one may arbitrarily operationalize a distinction here – between more-bounded and less-bounded – but for all intellectually serious epistemologists, psychologists, cognitive scientists and anthropologists, ‘rationality’ is bounded at least by human limits: our processing resources, our cultural resources, our working memory, our time to reach decision, our access to experts, our epistemic perspective, generally conceived.

The two families of theory, internalism and externalism, have then, as an outcome of their conflict, each been forced to draw the same distinction – between two separate desiderata of adequacy. Under severe pressure from the other’s arguments, each has been forced to abandon any pretensions to meet one desideratum of adequacy. Between them, they account for both desiderata; separately, they each account for one alone.

2.5 Irenic resolution or Gordian (knot) threat?

What is not often flagged is that this task separation at once offers us both the promise of an irenic resolution of some tangled traditional disputes in epistemology and the threat that any such resolution may be Gordian in nature. We may see as irenic a solution that promises a simple division of labour in epistemology. Many erstwhile disputes are then not so much solved as dissolved. Internalist accounts alone offer us the resources to satisfy the regulative desideratum, yet must disavow any claim to satisfy the theoretical desideratum. This surely leaves such accounts uniquely well suited to offer us our position on epistemic rationality (or if you prefer – cf. the above – epistemic justification). And externalist accounts alone offer us the resources to satisfy the theoretical desideratum, yet must disavow any claim to satisfy the regulative desideratum. This surely leaves such accounts uniquely well suited to offer us our position on knowledge. The fact remains, however, that a number of knotty problems will have been severed rather than untied. For we will end up with an account of knowledge that openly flouts paying even lip service to the regulative desideratum of adequacy; and an account of rationality that openly flouts paying even lip service to the theoretical desideratum of adequacy. We have seen that there are powerful motivations to go down this route; but were we to do so, could we abide the destination in which we would find ourselves?

2.5.1 Objections to the Gordian threat: The virtues objection

Virtues theorists in both ethics (Aristotle 2000) and epistemology (Zagzebski 1996) are wont to claim that we have achieved our epistemic end (most commonly knowledge) or our ethical end (sometimes the good, sometimes the right) just in case we have maximized satisfaction of both desiderata: theoretical and regulative. They will deny that we have achieved our success state should only one desideratum be satisfied; thus they will deny that drawing this third distinction solves or dissolves any or many of the perennial disputes found in normative epistemology.

Response: Stipulative

As I have argued at length in Lockie (2008), this objection is merely stipulative. We, all of us (pro- or anti-virtues theory), can and do recognize these two desiderata, and may identify in any given case whether this or that desideratum has separately been satisfied. As distinct axiological projects, delineating distinct axiological properties, they exist (virtues theorists do not typically deny this – nor can they). One may, after recognition of this truth, stipulate that ‘virtue’, now employed as a term of art, applies only when both desiderata are met (e.g. Zagzebski 1996); and if this is felt a useful (stipulative) restriction of our philosophical terminology, then fine. What cannot be done to win anything other than a terminological victory is to specify that knowledge (say) or rationality (say) require this stipulatively so-defined conjoint state of ‘virtue’ to be met; and thus that a candidate account of knowledge, say, which (suppose) brilliantly meets several theoretical desiderata, is to be dismissed for failing to meet certain wholly distinct regulative desiderata – thus failing to be a state of virtue, as stipulatively so defined. It is noteworthy that non-Aristotelian conceptions of virtue, particularly the Stoic (Annas 2003), recognize this point and tend to restrict their account of the ‘virtuous’ to one satisfying the regulative desideratum alone: of which more in the next sub-section.

2.5.2 Objections to the Gordian approach: The ‘violated intuitions’ objection

Envisage a candidate externalist theory of knowledge, one which sets out solely to address the theoretical desideratum, perhaps offering a very promising candidate to satisfy this desideratum, yet does so in a way that flouts the regulative desideratum in its entirety (perhaps it permits very ‘lucky’ or irresponsibly acquired knowledge – take Sartwell (1991, 1992) as a paradigm: the claim that knowledge is merely true belief). Or envisage a candidate internalist theory of rationality that sets out solely to address the regulative desideratum, perhaps offering a very promising candidate to satisfy this desideratum, yet does so in a way that flouts the theoretical desideratum in its entirety (perhaps it permits objectively very awry, radically false, yet putatively rational beliefs – take Foley6 (1993) as a paradigm: the claim that rationality consists simply in being justified by our own deepest intellectual standards). It will be protested (it routinely is protested) that suchlike theories ‘violate our intuitions’ (sometimes, our ‘core’ intuitions) and that this is an awful thing – so awful that we must reject the abrupt divorce between theoretical and regulative accounts of epistemic value: an ordinary language/‘conceptual analysis’/intuitions-driven metaphilosophy establishes we must satisfy both desiderata in accounting for knowledge or in accounting for rationality.

Response: Abandon the indefensible metaphilosophy

When our intuitions are outraged by, say, an account which has it that an agent knows yet wholly fails to address the regulative desideratum, or is rational yet wholly fails to satisfy the theoretical desideratum, social-cognitive psychologists refer to (and dismiss) this type of phenomenon as a named species of cognitive error: a halo effect. We tacitly suppose a beautiful person must be good, and a good person must be wise … and a person who has achieved one epistemic success state must possess another; but it is not so. Our feelings of oddness at attributing knowledge to someone who has not regulated her thought well (Sartwell 1991, 1992; Lockie 2004, 2008) or rationality to someone operating under a massive framework of false beliefs (Foley 1993; Lockie 2016a,b) are just that: mere feelings of oddness. Our three major epistemic distinctions (knowledge versus rationality, internalism versus externalism, regulative versus theoretical) are all of them theory driven terms of art. The view that an argument to a position that is driven by fundamental epistemic theory should nevertheless be put in full reverse when it militates against ordinary language ‘intuitions’ (connotations, resonances, ‘tone’) that do not answer to anything like the constraints which shaped and motivated that argument’s development is quite unacceptable. Affording a priority to such intuitions over fundamental epistemic theory rests on an indefensible (and presently very hard-pressed) tacit, framework metaphilosophy. There is no reason at all why those of us who are normative epistemologists should cede all the arguments against conceptual analysis to the naturalists. The ‘violated intuitions’ objection (better: tacit conceptual framework) is dealt with exhaustively in Lockie 2004, 2008, and especially 2014b), where the metaphilosophy that underpins it is subjected to sustained critical pressure. The arguments there cannot be given further summary at this stage.

The conjunction of Sections 2.5.1 & 2.5.2: They don’t sit well together

When the virtues objection is conjoined with the ‘violated intuitions’ objection, an interesting tension is manifest: the ordinary language intuitions appear to militate against the virtues account. As the present author and others have previously noted (against, for instance, Zagzebski 1996), the ordinary resonance and normative connotations of calling someone a ‘virtuous’ character suggest we identify this state with a satisfaction of the regulative desideratum alone – whether in ethics or epistemology (Lockie 2008). This is a point emphasized by the Stoic (as opposed to the Aristotelian) tradition in virtue theory, and noted in their different ways by Russell (1996), Annas (2003) and others:

… men everywhere give the name of virtue to those actions, which amongst them are judged praiseworthy; and call that vice which they account blamable … (Locke 1975: II,28; cited in Goldman 2001: 30)

2.5.3 Objections to the Gordian approach: Impoverished justification is too cheap a notion

Nottelmann (2013) has an important discussion of blameless belief where this be cut away from other, more objective notions:

blamelessness in the minimal sense of non-blameworthiness sometimes comes cheaply. In fact too cheaply, it would seem, to take a version of [the deontic conception of epistemic justification] predicated on plain blamelessness seriously as a conception of [epistemic justification]. The problem is that there could be beliefs which are blameless, only because it makes no sense to blame the believer for holding them. But intuitively it would then seem that it makes as little sense to evaluate such beliefs as epistemically justified … suppose that each of us is for some reason born with an ineradicable7 belief, for or against which we may never obtain relevant evidence. … Blaming us for this belief, if it is truly innate and ineradicable, seems strange. But so does declaring it somehow epistemically justified. (Nottelmann 2013: 2236)

Nottelmann is right here, as far as it goes, but he has surely just identified that ‘blamelessness’8 (which in this context may hold place for any justificatory notion that solely answers to the regulative desideratum) is an incomplete notion of justification – and we established that ourselves. Of course, an important axiological notion in epistemology concerns objective truth conduciveness; but that is just a different notion to the deontic notion. Equally, it may sometimes be important to conjoin our two notions of epistemic justification – internal and external – but they are distinct notions for all that. What matters is that we acknowledge that the principle OIC and our epistemic limitations force on us a notion of perspectivally limited ‘blameless’ (if you must) justification, however much it jars the ears: this jarring is just a halo effect. Suppose, to take Nottelmann’s example, we consider ineradicable beliefs, or cognitive limitations forced upon us by our biological natures (à la Kant, Chomsky and McGinn): were there such beliefs/limitations, it would seem to me to be indeed correct to say we would then be, as a species, blameless and as justified as we can be in holding these (nevertheless false) beliefs. The same thing goes for beliefs that are a product of our cultural–historical rather than biological limitations: Newton blamelessly believed in absolute simultaneity – he was justified in this (false) belief9; Alston’s tribesman blamelessly believes in his culture’s metaphysical world-view, and so on. We all have our limits. Justification in this important sense applies to us thinking as well as we can within these limits.

2.5.4 The situation that confronts us

There is a general objection to any attempt to efface this distinction. Any insistence that we should elide or conjoin the twin desiderata we have identified thus far faces the charge that this would be simply to ignore the situation that confronts us as epistemic agents. By hypothesis, in facing a decision, we have no ‘marker’ of which of our beliefs are true and which false – if we had, epistemology as an enterprise, and the questions we are addressing, would be superfluous. We have our beliefs, both true and false, and must move forward from these altogether to find out the justified ones – those likely to be of facts. This just is the regulative project. A consideration of one engaged with this project (and we are all engaged with this project) leaves us with no choice but to acknowledge the agent’s epistemic limitations, his fallibility and frailty, the fact that his epistemic resources may not (and often will not) be up to the task. This situation simply confronts us, each of us, qua epistemic agent, qua inquirer in the world, and in acknowledging it we must recognize two things. First, notwithstanding the possibility that in such situations the agent may unavoidably be led into error, there is a core, vital sense in which in such a situation he may nevertheless be justified – and will be justified should he marshal his resources as effectively as his perspectival limitations permit. Second, that in such a situation, he is nevertheless avowedly in error – that is, as much as he may have satisfied one desideratum and achieved justification thereby, he has failed to satisfy another undoubted aim of epistemology and lacks a fundamental epistemic value thereby. Conversely, when our agent, despite guiding his thought badly, has attained the truth, or some other objectively desirable factive state or relation to the world, we are describing at once both a type of epistemic success and a distinct type of epistemic failure. We have no option but to recognize these types of achievement (and failure) as distinct. There is a double dissociation between these two desiderata. Insisting that we must abandon two separate and distinct forms of assessment of the epistemic agent ignores much of what it is to be an agent in the world: the subject of decision and normative appraisal consequent upon that decision.

2.5.5 The Foley divorce

Passim in the internalist/externalist literature (indeed, in epistemology per se, at least since Descartes) we see arguments establishing – surely conclusively – that one may be as justified as one can make oneself, yet still fall radically short of the truth; or one may have as reliable and objective a connection with the truth as you like, yet have attained this truth through intellectual conduct that was reckless, deplorable or remiss. This double dissociation – the basis for the Foley divorce – gives us two points of assessment for an epistemic subject in a situation: internally justified? (yes/no); and externally justified? (yes/no). These map a grid of four positions in logical space (or if, as is preferable, these contrast-pairs be thought of as continuous rather than discrete, a space marked out by two bipolar, Cartesian dimensions) (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 The epistemic circumplex

Famous and not-so-famous thought experiments can be inserted at will into the top right and bottom left quadrants of Figure 2.1; I have mentioned one esoteric and one quotidian case for each, but there are of course a very large number of such cases, any of which would serve for use as examples. Should I be BonJour’s (1985) reliable clairvoyant, then I will face Descartes’ (1931: 176) charge: ‘blame of misusing my freedom.’ And for every recherché thought experiment, there is a quotidian case (that is: the dissociation is not merely conceptual) – as for the case of Greco’s truck, bearing down upon me, leading me to leap out of the way despite no discharge of any epistemic responsibility contributing to my state of knowledge (Greco 2002: 296). Similarly, one may discharge one’s obligations diligently yet be wholly unable to achieve the truth or avoid falsity – whether through being a victim of a New (actually not so new) Evil Demon, or simply by being an agent embedded within a sociocognitive milieu that does not permit one to attain the truth (as for Alston’s 1985 tribesman, brought up to accept the traditions of his tribe as authoritative, diligently working within these resources, with the epistemic resources of other intellectual perspectives being wholly beyond his compass – cf. Lockie 2016a,b).

Keeping these two axes of epistemic appraisal as just that – two – yields a richer form of epistemic appraisal (far richer) than any species of epistemic appraisal forced on us if we elide these issues into one categorical measure. If there is one lesson we must learn from four hundred years of epistemology after Descartes, it is that appraisal of the epistemic status of agents requires taking a separate register to situate them on both the orthogonal dimensions identified above – for, in categorical terms, there is the possibility of them occupying any of the four positions identified.

2.6 Normative epistemology in light of this distinction

2.6.1 Knowledge/rationality and the regulative–theoretical distinction

As stated at the outset, the existence of this third (regulative–theoretical) distinction is hardly esoteric knowledge in epistemology. Yet how seriously has it been taken by those seeking to develop accounts on either side of our first distinction – accounts of rationality or of knowledge? Does an awareness of the theoretical–regulative distinction really inform theory construction in epistemology? Periodically, the philosophical community approaches the insight that an epistemology that developed and shaped accounts of either rationality or knowledge in light solely of the appropriate desideratum for that item might make space for Gordian treatments of certain epistemic problems: shocking accounts that otherwise would be scorned, marginalized or simply not entertained. But then, having approached such insights, the world of academic epistemology just seems to veer away.

So, over more than a decade, a long overdue consideration of the Meno value problem has been underway (via, for example, the growing literature on the ‘Swamping Problem’; and variants of Zagzebski’s (2003) ‘espresso machine’ analogy). But the terms under which this problem has been discussed are desperately prescribed; participants in these debates seem, at the level of framework presupposition, not to entertain the possibility of a radically theoretical account – say, of the need to address the challenge represented by a genuinely Theaetetan10 theory of knowledge (Sartwell 1991, 1992, Plato 1956: 97a–b, Plato 1992: 187b). Where such accounts are entertained, they are taken unargued to be merely a reductio of any theory that entails them (Chisholm 1988: 287). From the other side of the internalist–externalist divide, the viability of extremely internalist accounts of rationality (e.g. ‘Foley rationality’: that rationality consists in being justified by our own deepest epistemic standards (Foley 1993)) are routinely disparaged on grounds that, for one who sees any such account as answerable solely to regulative considerations, are plainly non sequiturs – of which more in Chapter 5 (and cf. Foley 2004).

2.6.2 Internalism/externalism and the regulative–theoretical distinction

The big challenge for intransigents on either side of the internalist–externalist distinction is to ask how much will remain of their respective hostile arguments after fully acknowledging this distinction concerning the desiderata for epistemic theories; and in particular after establishing that internalists and externalists alike are each already committed to their specific account satisfying only one of these distinct desiderata. Isn’t this just to effect a (possibly unwelcome) irenic resolution of much that was hitherto in vehement dispute? Internalism satisfies the regulative desideratum of adequacy and gives us our account of rationality. Externalism satisfies the theoretical desideratum of adequacy and gives us our account of knowledge. There is then plenty still to disagree about, like: what is the correct externalist theory of knowledge? What is the correct internalist theory of rationality? And in particular: what would an externalist theory of knowledge look like were this theory to be developed wholly and solely with a view to addressing the theoretical desideratum? What would an internalist theory of rationality look like were this theory to be developed wholly and solely with a view to addressing the regulative desideratum? Should such questions be addressed with, and motivated by, an explicit awareness of the foregoing meta-epistemic considerations, the answers to them would be likely to prove very interesting indeed. But that such a state of affairs should come to pass would require a Rubicon to be crossed in modern epistemology.

What, minimally, an informed awareness of these meta-epistemic issues should lead us to question is how much point there is to the familiar dialectic which occurs when partisans for the one approach upbraid partisans for the other approach on the basis of, say, the inability of this (avowedly theoretical) account to satisfy this (clearly regulative) desideratum – or vice versa. Further, these meta-epistemic issues should lead us to question the requirement that one and the same normative epistemic theory should answer to (indeed maximize) both desiderata at once. There are strong reasons to doubt whether any one account can satisfy both desiderata. Within epistemology, we need to confront this situation and entertain the radical conclusions that appear to follow from it.