Epistemic Deontologism and Control

3.1 The structure of the debate

Few psychologically healthy individuals, naïve to our epistemic debates, doubt that they have considerable control over their mental lives, but many epistemologists have taken such a stance to be problematic – or at least have sought to ‘problematize’ certain (as they see it) widespread conceptions of the degree and nature of our intellectual control. Criticizing the notion that we possess significant levels of control over our mental lives constitutes the jumping off point for the major lines of attack against epistemic deontologism. Deontological appraisal generally (in ethics no less than epistemology) requires that the agent possesses responsibility-appropriate powers of control. Thus, for example, the motivation underpinning hard-determinist objections to ethical deontology is immediately obvious. However, as regards specifically epistemic deontologism, arguments we shall shortly consider claim that, without ever approaching the metaphysical or scientific commitments of hard determinism, a kind of control fit to underwrite deontological appraisal could not be possible or at least is not actual. So, deontological epistemic appraisal is argued to be indefensible.

Among some who are not wholly convinced by such arguments, there is nevertheless a more positive concern as to how an agential, deontologically appropriate species of intellectual control might be possible, or could be actual. This more positive project also needs to be addressed – and will be, at length.

There are three common ways these worries about deontologically appropriate control have been expressed. The first two involve slightly different ways of defending doxastic involuntarism (Premise iii in the following argument); the third may be shoe-horned into this argument via its Premise iii, but is in principle rather more general.

i. Epistemic deontologism involves intellectual ‘oughts’ (Df).

ii. ‘Ought’ implies ‘can’ (a priori).

iii. We can’t choose our beliefs (doxastic involuntarism).

iv. So epistemic deontologism is indefensible.

First argument: involuntarism is obvious from the armchair. Second argument: involuntarism is the verdict of modern science. Third argument (what I shall call the Bias Argument): the two terms making up the conjoint term ‘epistemic freedom’ are intrinsically opposed – freedom can only bias belief formation. Our beliefs must be forced (by the facts, the world) if they are to satisfy genuinely epistemic (world-to-mind, not mind-to-world) desiderata – if they are to register the truth. The bias argument is an important one and needs a response; however, I don’t want to structure this chapter with this argument, so will bracket it, to address it exhaustively in the next chapter.

Rebutting these objections is the negative aim of this chapter, and to some extent the next. Positively, however, giving an account (a non-definitional account) of what our powers of intellectual freedom and control consist in is by far the more important task of these two chapters. I shall argue in the second half of this chapter and all of the next that what we need in order to be held responsible for our beliefs is a freedom of executive functioning, where this involves the self-regulation of our thought and action – and that we, as undamaged human agents, possess such powers: remarkable powers of intellectual agency.

Doxastic involuntarism: Armchair and scientific

Claims of doxastic involuntarism are the crucial premise in the first and second arguments for the untenability of epistemic deontologism, with these arguments differing only in the way these claims are defended. One defence is armchair, whether conceptual or empirical: ‘My argument, if it can be called that, simply consists in asking you to consider whether you have any such powers. Can you, at this moment, start to believe that the United States is still a colony of Great Britain, just by deciding to do so?’ (Alston 1988 in his 1989b: 122). The second argument is that doxastic involuntarism is the clear verdict of modern science. Regularly in discussion and sometimes in print, one encounters from philosophers (not just epistemologists) a conception of cognition most generally as unconscious, mandatory, automatic, autonomous, non-rational, fast, parallel, etc. – Nottelmann’s (2006: 562) description of belief formation as involving processes of ‘non-intentional reflex reactions’: triggered processes as little under our control as, say, digestion (Chrisman 2008).

Responses

In response to the involuntarist objections, four defences of epistemic deontologism open up: 1. One may reject ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ (OIC). 2. One may claim one can directly choose one’s beliefs. 3. One may claim that one can indirectly choose one’s beliefs. 4. One may claim that the freedom (the ‘can’) needed to underpin epistemic deontologism involves regulative control of one’s cognition, yet does not normally involve choosing beliefs in any sense, direct or indirect. Defending 4 with the claim that we possess a freedom of self-regulative cognition (of executive functioning) is the positive aim of this chapter and the next; but before we get to this, the negative aim will predominate.

3.2 Belief choice is not to the point

I reject 1, defending OIC in the free will literature at length in Chapter 6 and Lockie (2014a) – though it has been defended epistemologically already in the preceding two chapters. I maintain that 2 is conceptually possible and (rarely) empirically actual – defending the existence of such cases in the self-deception literature in Lockie (2003a).1 However, in epistemology (as opposed to philosophy of mind or psychopathology), such phenomena are largely tangential to the issues of concern to us. We should make almost no reliance upon 2 in defending an epistemic deontology that is meant to have very widespread applicability to human intellectual conduct, including, importantly, commendable cognitive conduct – for direct doxastic voluntarism of this unusual variety is generally a sign of epistemically unjustified belief. A freedom to choose beliefs immediately (‘directly’) is not necessary for epistemically deontological appraisal, though its rare instances may sometimes be sufficient for said deontic appraisal – most commonly, however, appraisal as an unjustified (say, self-deceiving) believer.

The ‘two-stage’ defence of involuntarism

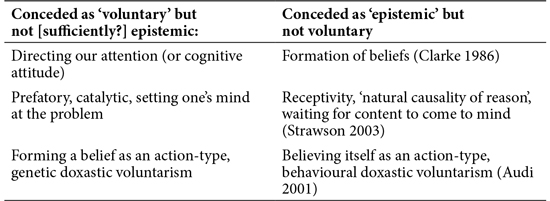

A freedom to choose beliefs directly is not only an odd conception of cognitive freedom and control, it is also an implausibly strong conception thereof. Although there are deontologists who defend 2 (notably Ginet 2001), they are by no means common. Many opponents of deontologism, however, take 2 as their main target. To the extent they seek to motivate this (and it does want for motivation), they typically do so by invoking a ‘two-stage’ defence of involuntarism. For example, early in these debates, Murray Clarke (1986) distinguished doxastic from ‘attitude’ voluntarism. The latter concerns voluntarism ‘with respect to directing our attention (or cognitive attitude), but not with respect to the formation of beliefs’ (Clarke 1986: 39, emphasis in the original). We get a distinction between the genuinely free and the genuinely epistemic. Motivating this distinction will be the major challenge for those who invoke it – and numbers do invoke it. Galen Strawson also mentions attention (among other things), but in summation comes closer to this: ‘the role of genuine action in thought is at best indirect. It is entirely prefatory, it is essentially – merely – catalytic’ (Strawson 2003: 231). He concedes that ‘there may well be a distinct, and distinctive, phenomenon of setting one’s mind in the direction of the problem … and this phenomenon, I think, may well be a matter of intentional action’ (loc. cit.) – but appears to regard this as a small concession, since the epistemic is what occurs (by definition?) after this: ‘The rest is waiting, receptivity: waiting for something to happen – waiting for content to come to mind, for the “natural causality of reason” to operate in one. There is I believe no action at all in reasoning and judging if these activities are considered independently of the preparatory, catalytic activity described above’ (Strawson 2003: 231). Audi (2001) distinguishes believing itself as an action-type from forming a belief as an action-type, in so doing deploying some proprietary terminology (respectively: ‘behavioural’ versus ‘genetic’ doxastic voluntarism).

Many more than these three authors have drawn this distinction, or something like it, using various terminology, but Clarke was amongst the first. In part, he will have been attempting to respond to the positions of Heil and early Kornblith: ‘It is not that one has a choice in the beliefs that one forms, but that one has a say in the procedures one undertakes that lead to their formation’ (Heil 1983: 363; cf. Kornblith 1983, but contrast Kornblith 2012, cf. also Alston 1985 in his 1989b: 91ff.). Heil and (early) Kornblith conceded that some such distinction as the above may be drawn, but simply, and correctly, denied that the left-hand (‘voluntary’) column of Table 3.1 was insufficiently epistemic. This position is close to my own; saving that I shall make my case borrowing heavily from the psychological sciences, which yield us greatly more resources than is offered by talk of ‘attention’ or ‘setting one’s mind at the problem’ or ‘procedures one undertakes …’ – of which more in the second half of this chapter and all of the next.

Table 3.1 Three versions of the same two-stage distinction

If this is simply to deny that the functions articulated in the left-hand column of Table 3.1 are, when fully and accurately described, ‘insufficiently epistemic’, noted above was the challenge for the involuntarist to motivate and defend his claims to the contrary. Such defences are relatively scant. Murray Clarke claimed ‘the internalist must accept doxastic voluntarism or she will not be able to claim that someone is justified or unjustified (i.e., epistemically irresponsible) in holding any particular belief’ (Clarke 1986: 40). This is a commendably explicit statement (statement rather more than argument) in a debate where the motivations for a refutation of strong, (direct, immediate) doxastic voluntarism are not always explicit; but made explicit, it appears indefensible without any need to appeal to science. Examples clearly undermining said statement abound through the epistemically deontological literature – here is one to add to these. Envisage a detective who has, throughout his police career, demonstrated a poor attitude, being lazy, egotistical, lacking due diligence, lacking moral seriousness and possessing a laissez-faire approach to his professional duties. These traits have what Kane (1996) calls a ‘tracing effect’ on his character development – exacerbating an already weak character to become markedly worse, foreclosing, at a later date, possibilities for good conduct that still existed at an earlier time (cf. Aristotle 2000: III, v, 1114a).2 Through assiduous flattery and unctuous professional networking, our detective becomes lead investigator in a murder investigation, where he fails to seal the crime scene early enough, he cross-contaminates the storage of DNA evidence and he fails to systematically track down, cross-reference and record all relevant witness statements. He also fails to study the witness statements and forensic evidence with sufficient rigour and intricacy, or think carefully and systematically enough about the evidence and the unfolding investigation in the way he has been trained throughout his police career. He believes what he subsequently believes (‘suspect x did it!’) with sincere conviction – but he is unjustified (deontically) because of his deplorable cognitive conduct, his wholesale epistemic irresponsibility. Let us suppose his late-stage final processes of belief formation and fixation (say, the micro-cognitive processes that occur subsequent to his poor conduct, intellectual and otherwise) are entirely involuntary; still, he is epistemically unjustified in a strongly deontic sense. To emphasize: these specifically doxastic voluntarism debates may, for whichever reason, interest the reader as self-standing issues in their own right; but for our purposes they are solely in the service of deciding the viability of epistemic deontologism.

One response on behalf of the involuntarist would be to maintain that cases like that of the detective are only cases of ethically deontic appraisability. However, beside the fact that the case as described does appear to pertain specifically to intellectual irresponsibility, it will anyway, more generally, be difficult to make this response against the epistemic deontologist without begging the question: the deontological tradition in epistemology has, since at least Clifford (in fact, since Locke, since Descartes – cf. Plantinga 1993) precisely seen epistemic justification as the ethics of belief. In any event, issues of epistemic deontology interpenetrate issues of ethical deontology. Neighbouring attempts to distinguish a voluntarism of motor actions (apt for ethical appraisal) rather than mental agency will be criticized in the next chapter’s assimilation of these issues to the situated and embodied cognition literature.

Another response on behalf of the involuntarist opponent of deontologism would be to hold that a defence of a specifically doxastic voluntarism is mandated for the deontologist because beliefs are the items we assess for epistemic justification. Perhaps (probably) the second quotation from Clarke above shows him approaching this as an argument. I must be able to choose my beliefs if I am to be deontically appraisable for holding my beliefs, as beliefs are just the things that we are in the business of appraising for epistemic justification.

However, noted right at the start of Chapter 1 was that in normative epistemology we are in the business of appraising much more than beliefs. We also, and more centrally, appraise thought processes, arguments and chains of reasoning by saying these are rational or irrational. In so doing, one also normatively appraises the epistemic status of the cognizer who possesses such beliefs, develops such chains of reasoning and makes these arguments. Indeed, it is plausible that beliefs per se are only derivatively deontically appraisable (though non-derivatively alethically appraisable) – appraisable from (say) the integrity of the cognitive conduct by which the agent formed them (e.g. Heil 1983; Kornblith 1983). If the deontological opponent of a doxastic voluntarist conception of epistemic freedom were in trouble on grounds that in epistemology we often speak as if some of the items that we may normatively assess are beliefs per se, then what of the position of the specifically doxastic involuntarist when faced by these other cases (of our need to normatively assess agents, thought processes, chains of reasoning?). Any belief we assess for epistemic justification is held by an agent, at the end of a belief-forming process (perhaps an involuntary process, but typically, as regards matters pertaining to the justification/rationality projects in normative epistemology, a chain of reasoning, or argument, or process of evidence gathering, or often explicit, often language-mediated ratiocination and dialectic).

Cases such as that of the detective are advanced in opposition to 2, the idea that deontic appraisability requires immediate, direct, doxastic voluntarism; but note that such cases scarcely rely upon or defend 3. We would not normally condemn the detective’s conduct on the ground that he failed to implement an indirect ability he possessed to bring about that or a different belief (‘suspect y did it!’). In such an investigation, he ought not to have tried to bring about any prior-specified belief, whether directly or indirectly: he ought to have conducted his investigation thoroughly, with due diligence and integrity, and followed the evidence where it led – position 4. A freedom to choose beliefs, even indirectly, is not normally required for epistemically deontological appraisal – and this is connected with point (c) of the three points (three ‘oddities’) listed below. The kind of freedom needed to underpin epistemic deontologism is overwhelmingly a freedom of mental action and cognitive conduct more generally (of executive control), not doxastic voluntarism. Before getting to this positive claim, three cautionary points need to be flagged, followed by a counterattack.

3.3 Three oddities about the negative arguments of the doxastic involuntarists

Point (a) is that the doxastic involuntarists have tended to emphasize very synchronic belief formation over diachronic belief formation. It is noted that the epistemic agent cannot typically choose to believe (say, a falsehood) at a specific instant, or very brief interval in time – or at least, that cases where he or she could would be most unusual and extreme. Epistemic conduct, however, is typically extended in time, involving cognitive processes, trains of thought, projects of inquiry – involving planning, sequencing, maintenance of mental set, coordination and control. These involve extended debates and dialectic (inner ratiocination and outer argument). Eventually, they may even interact diachronically with the development of intellectual character. An immediate point-instant ability to form a belief is an odd characterization of what is normally required for good or bad cognitive conduct. Revealingly, its immediacy is a characteristic more obviously applicable to automatic and involuntary processing (e.g. perceptual processing) than to the kinds of higher mental processes apt for normative epistemic appraisal – say, as rational or irrational.

The ‘final pathway’

Involuntarists are intermittently sensitive to this point, and where they try to respond to it, they commonly do so by moving to something like a final pathway (/final process) position. It is conceded that much of the agent’s epistemic conduct, like her actions (including mental actions) in pursuit of inquiry, are chosen, hence deontically appraisable in some extended sense – perhaps à la Clarke’s ‘attitude voluntarism’ or Audi’s ‘forming a belief as an action-type’. But it is demurred that the final pathway to belief formation/fixation that is consequent upon this avowedly voluntary action is, as a matter either of psychological fact or something stronger, involuntary: ‘[W]e can voluntarily influence our attention or attitude toward belief acquisition, but maintain that once this process is completed, the beliefs we do acquire are forced’ (Clarke 1986: 39, emphases in original). ‘Psychological fact or …’? The risk of an equivocation between stating an empirical falsehood or an empty formalism should be obvious to the reader. Pick any case of putatively deontically appraisable epistemic conduct, whether commendable or remiss. Is it really deontically appraisable? No, says the adherent of this approach – because after all, the final pathway to belief formation/fixation must have been involuntary. This ‘final pathway’ can presumably be made as final as is needed to make this claim come out as true. At the point of belief formation, beliefs must be involuntary. What is this point? Perhaps a vanishing point. At some final moment, belief formation just happens, is triggered. Some ‘voluntarists’ may be moved to deny this, but I don’t feel the deontologist is required to. If I lure a man to a bridge, then pose him as for a photograph, then push him off, at some final point gravity takes over. My action is deontically appraisable for all that.

Point (b) is that the literature repeatedly argues for involuntarism on the basis that we cannot choose to believe unjustified and obviously untrue things. Examples of this are ubiquitous: Alston’s (1988) argument that it is not possible for me to believe that the US is still a colony of Britain; Feldman’s (2001) argument that it is not possible for me to inculcate ‘flat earth’ beliefs; Plantinga’s (1993) argument that it is not possible for me to foster a belief that the population of China is less than that of the US; Chrisman’s (2008) claim that it is not possible for me to believe that Hell is a bar in Chapel Hill. Often, this point is made in terms of our inability to bring about belief (at least directly) for practical reasons (say, in exchange for cash incentives). But (i) the deontologist is not defending the ability of agents’ to discharge their responsibilities to think badly, for of course he is committed to the position that they have no such responsibilities; the deontologist is defending the ability of agents to discharge their responsibilities to think well, and our right to judge certain people as culpable who have in fact thought badly yet could have thought better. And (ii) the deontologist is of course not defending the ability of agents to bring about belief for non-epistemic reasons (Hieronymi’s (2005) ‘extrinsic reasons’ – money, say). The deontologist is defending the ability of agents to discharge their epistemic responsibilities in forming their beliefs well (Hieronymi’s ‘constitutive reasons’) rather than allowing their belief-forming processes to be conducted poorly.

Consider in regard to (b) Feldman’s ‘flat earth’ example. Feldman evaluates and rejects a response to Alston’s doxastic involuntarism argument made by a deontologist appealing to our possession of indirect control over our beliefs. Feldman notes, of the flat-earther’s efforts to remove his existing ‘round earth’ beliefs: ‘I can’t simply set out on a course of action that will almost surely result in my belief being changed’ (Feldman 2001: 81, emphasis added). He then notes: ‘I might enrol in the flat earth society, read conspiracy literature asserting that the satellite photos are all phony, and so on … But this gets us, at most, indirect voluntary influence and this is not the sort of effective voluntary control required to refute The [in]Voluntarism Argument’ (loc. cit.). Consider, though, an inversion of Feldman’s case: a person in the grip of such a delusion, urged by his epistemic better nature, or a responsible friend, to rid himself of his irrational belief. He can wallow in his epistemic irresponsibility, his conformity to the flat-earth cult and the wilder shores of Internet conspiracy theory addiction. Or he could enrol in an online NASA-sponsored astronomy course, read cult-deprogramming literature, listen to the efforts of friends and family to reach him, carefully study the satellite photos and so on. This effort after intellectual honesty (and mental health) gets him Feldman’s ‘indirect voluntary influence’ and, pace Feldman, this is exactly the sort of effective voluntary control required to refute the [in]Voluntarism Argument.

Point (c) is that the beliefs, considered as candidates for voluntarism or involuntarism, are typically typed by their contents, specified in advance of the initiation of the belief-forming process – cf. the quotation from Feldman, flagged above. We are invited to consider whether we can freely choose, prior to any process of truth-directed ratiocination, to believe p: that the earth is flat, or q: that the population of China is less than that of the US, etc. We are not invited to consider the inquiring subject and ask whether she is free to diligently, or instead reprehensibly, form beliefs (not already typed by their contents) about, say, physical or human geography. But it is the latter that the epistemic deontologist should be seeking to defend. No responsibly inquiring subject would normally start from a proposition, typed by its content, and seek after ways to make this her belief. Such cases (e.g. in political or religious contexts – the ‘party line’, a point of doctrinal orthodoxy) would rather be paradigms of unjustified belief formation.

3.4 The involuntarist also has a position to defend

This debate is not only about whether the deontologist can defend sufficient psychological freedom to underpin her account of epistemic value. From Clifford onwards (indeed, from Descartes onward), cases have been advanced illustrating agents who appear apt for deontic appraisal – I have given one above (the detective) and shall give others below. In light of the facility with which such examples can be constructed, and their intrinsic plausibility, it would be regrettable if the dialectic were allowed to switch entirely to what the deontologist has to defend. If there are cases that appear strongly apt for deontic epistemic appraisal, then the involuntarist will face the charge that he does not furnish us with the resources to deploy these deontic appraisals. I suggest, in fact, such cases will face involuntarists with a nasty, nested dilemma. Either they concede that some such agents are deontically epistemically appraisable, or they have work to do to defend the improbable thesis that none of them are. If they do concede that some such cases describe agents who are deontically epistemically appraisable, then they face a second dilemma, as to whether these agents have ‘doxastic voluntarism’ – this term given such meaning as the involuntarist may articulate for himself (typically in sense 2, occasionally in sense 3, as above; possibly in some other senses). Should the involuntarist maintain that such deontically appraisable agents do have ‘doxastic voluntarism’, he loses his case of course; but should he maintain that they don’t, then epistemic deontological appraisability is shown to be quite untouched by doxastic involuntarism – as the involuntarist himself has been free to fix this notion. To repeat: in what follows, I am only concerned to defend epistemic deontology – nothing else in these debates is of concern to me.

If doxastic involuntarism does not permit us to deontically appraise cases such as that of the detective, and others developed over the last 400 years from Descartes – cases apparently apt for such appraisal – then so much the worse for that position. But if it does, then doxastic involuntarism leaves the core, central argument against epistemic deontology untouched.

The question nevertheless emerges as to how the agent may have the intellectual freedom to reason with either integrity or its absence. That question may exercise even those who do not doubt that agents have this freedom, and may motivate the doubts in those who do. Beginning to answer it commences after the presentation of the final (bias argument) objection to epistemic agency, and that begins after some final under-gardening.

3.5 Ethics, epistemology and the desire-based conception of freedom

The arguments regarding doxastic voluntarism (especially where involving the three features (a)–(c) noted above) make illuminating, though typically unacknowledged connections with arguments in ethics regarding the distinct positions of ethical (not epistemic) internalism and externalism – and more generally with disputes between ethical determinists and their opponents as to whether we must be determined to action by what we take to be the right.3 Doxastic voluntarism then becomes structurally similar to a position taken as a target by (moral) internalist–cognitivists and attributed by them to their (moral) externalist opponents. This target position is that the moral externalist’s freedom to act or withhold action in the presence of a moral belief would have to consist in the presence or absence of a desire thus to act on that belief – and that the imperatives of morality will therefore be hypothetical on possession of such desires. This (largely straw) position is often opposed by ethical internalists on the grounds that desires are not apt to represent the world or have truth predicated of them; thus that any such ‘freedom’ – to act or not on our moral beliefs – could only underwrite a non-cognitivist approach. (This desires-based position is also commonly assumed to be regressive.) Moral internalists see the cognitivist as committed to the position that ‘we are not volunteers in the army of duty’ (Kant – in Foot 1978: 170)4: that we are determined to action directly by our moral beliefs.

The tacit, framework reasoning of such ethical internalists is that either we are entirely determined to moral action by what we take to be morally true (cognitivist ethical internalism) or we are (partly) determined by a desire (non-cognitivist ethical externalism). They tacitly already embrace the idea that we are determined to moral action. They tacitly reject the possibility of an ethically externalist cognitivism because it is assumed that to be free to act or not on our moral beliefs would have to mean we could choose to be moral or not; and the difference between one who chooses to be moral and one who does not must be that the one who chooses to be moral is determined to action by a different desire to the one who does not. And desires are taken to be intrinsically non-cognitivist: that is, unlike beliefs, they are not fit to represent how the world is and thus be true or false.

But unless ‘desire’ here is merely a harmless synonym for choice, this framework of argument is fallacious. Contra moral internalism, two people can choose to act differently in a situation despite sharing the same moral belief about that situation (‘I should not be cruel to that man’). And in opposition to a certain very atomistic conception of belief–desire psychology, this difference in action need not be ‘hypothetical’ on the presence of different desires-as-real-mental-items (desire-item: to be cruel or not). The two people might just have the same moral beliefs in different minds. Beliefs don’t determine moral action, desires don’t determine moral action; the person determines moral action (in response to his or her beliefs). The properties of the person (e.g. her powers of moral agency) will not be an associative sum of the properties of her beliefs, desires or any other sub-personal parts. These ‘parts’ (beliefs, desires or other) do not have a prior direction and degree of moral motivation associated with them – prior to combination in a mind, that is (cf. Lockie 1998).

The bias argument

Now apply the lessons of this debate to epistemology. The epistemic externalist’s opponent was held to maintain that a deontic conception of justification required a neo-Humean desires-based freedom of ‘doxastic voluntarism’. Such freedom meant one had to be able to choose one’s prior-specified beliefs p, q, r. Since the ground for choosing was presumed to have to be a desire, attributed to the epistemic internalist was a strange kind of non-cognitive (non-epistemic, ‘extrinsic’) conception of belief formation, whereby our belief was hypothetical on the presence of said desire – say, the (aesthetic? financial?) desire to acquire the belief that the earth is flat, etc. The position held in forced-choice opposition here was that we do not have any choice in our belief formation – this being wholly out of our control. So you’re either (non-epistemically, non-cognitively) ‘free’ to form a belief about the world on the ground that you desire it should be thus and so – and that’s no kind of epistemic freedom. Or, you’re compelled to belief by the way you take the world to be – and that’s no kind of epistemic freedom.5

What we believe, when all is going well, has nothing to do with what we want, and this is precisely why the reasoning mechanisms may operate so well. Our wants have nothing to do with the reasons we have for belief … belief formation which involved agency, and thus allowed our desires to play a role in the beliefs we form, would thus pervert the process. (Kornblith 2012: 96)

This, though, involves a false dilemma – one engendered by a picture of cognition as either passive, automatic, ‘uncontaminated’ input information, a veridical unvarnished copy of the world; or a partially contaminated, desires-affected, ‘non-cognitive’ intrusion into/projection onto that copy. This picture of things ignores our role as inquirers, as active seekers after truth. It is qua inquirer that we are assessed for epistemic normativity most generally (that is, as opposed to mere afferent psychological processing efficiency); and particularly it is qua inquirer, as active seeker after truth, that we are assessed for epistemic rationality. These powers – of inquiry, of intellectual agency – do not stop at the periphery: at, say, the motor actions that initiate, accompany and subserve inquiry. In rational human thought, the efferent pervasively interpenetrates the afferent. We are not merely passive receivers of sensory, mnemonic, etc., information. We are epistemic agents. At many levels, we actively control our cognition. That is what it is to be a human cognizer; or at least, an undamaged human cognizer: one capable of appraisal for epistemic rationality at all. In the chapter to come, we confront (exhaustively) the picture of epistemology, and concomitant conception of psychology, which opposes this; we make good upon a conception of intellectual agency that emphasizes the role of the inquirer’s active powers – capacities not simply for reception, but very high-level powers of executive control. Introducing the material that these claims are built upon will take up the remainder of this chapter. Making good on these claims will take up the whole of the next.

3.6 An introduction to the executive functions

The executive functions (EF) are a name for the highest cognitive abilities we possess, those involving our capacity to self-regulate – to author and control our thoughts and actions. These are the capacities most central to our intellectual agency – indeed, to our agency simpliciter. The EFs subserve our ability to control and initiate our other cognitive operations, to plan, schedule, implement, monitor, adjust, integrate and inhibit: to direct our own thought. They (in addition to language and culture) distinguish us in degree, and to a very considerable extent in kind, from other animals. Although an umbrella term for many distinct families of cognitive process (how many being a major controversy), they are marvellously integrated and coordinated in actual functioning. They are significantly mediated by the frontal lobes, though to what extent, and what degree of localization, being another major controversy – other brain regions being known to be of importance also, quite apart from other, lower brain regions being tasked, scheduled, coordinated and directed by the executive as a matter of course.

Executive functioning (also ‘EF’) involves behaviour or cognition being more or less effortfully guided to a goal. It involves the ability to choose which sequence or strategy will best allow a goal to be attained. It involves setting said goals in the first place. It involves sub-goal setting. It involves ongoing re-prioritization of goals. It involves planning and modifying plans. These are active mental powers. They involve control. They involve our capacities for creative thought. They are reflexive – they apply to each other at the level of these processes’ mutual interaction, and then again, at the agential level – in ways we consider below. They may involve insight, and sometimes (in some situations) a distinctive phenomenology. Many are value laden (some appear to subserve deontic thought, some subserve ethical thought more generally, some are ‘socioaffective’ more generally still) – although these ‘hot’ cognitive powers integrate closely with the ‘cold’. They involve our capacities to direct our own thoughts and actions, and as such they are metapsychological abilities: the highest we are known to possess. They involve our capacities for many kinds of cognitive monitoring. Many of them involve conscious control, and few of them are highly automatic (though they moderate and direct and integrate systemically with many lower-brain automatic processes, and of course at the level of actual implementation, even conscious processes may be instantiated by sub-personal mechanisms). They involve our capacity both for cognitive flexibility (e.g. switching between tasks); and, conversely, for intellectual persistence (persevering at a task, motivation, effort). They involve control of action and thought over distances of time and space that are radically impossible for other animals, and thus a sense of self over time and space that is not possessed by lesser animals (representing oneself and one’s goals across time and space is what is involved when one ‘self-regulates’). They subserve our capacities for problem solving and reasoning and intellectual fluency, including language-mediated fluency (e.g. our language-mediated inner thought, and the cognitive control regulated by said thought). They concern our capacity for regulative top-down direction and integrated scheduling of our other cognitive powers. They underpin most of our intellectual agency. Taken at an appropriate level of description, I believe that little of this summary paragraph is open to dispute; though once we move beyond such explicative, introductory levels of description to, for example, the process level, just about everything else is.

The chief objection to epistemic deontologism follows from OIC, noting that deontological epistemic appraisal requires/presupposes a conception of intellectual freedom (typically involving a highly contrived notion of ‘doxastic voluntarism’) and that either a moment’s armchair consideration or a little (bluff) familiarity with the sciences of lower-level (e.g. sensory–motor) cognition indicates that we do not have said (proprietary) voluntary control of our cognition. We are meant thereby to conclude that epistemic deontologism is indefensible. Against this assembly of arguments, I contend that the intellectual control we appraise deontologically is and ought to be executive control; that we have said executive control, that it is apt for deontological appraisal and that this is the type of self-regulated intellectual agency that the deontologist should and does commit to being appraisable for being dutiful or remiss.

The concept of EF first emerged out of clinical neurology and its study of frontal lobe function and dysfunction. Commonly, even in non-clinical texts, the EFs are introduced via the example of one or other of the famous clinical cases illustrating their impairment, here Lezak’s ‘Dr. P.’ – a hand surgeon who was himself the victim of frontal lobe damage due to hypoxia during minor surgery:

This damage had profound negative consequences on his mental functioning, compromising his ability to plan, to adapt to change, and to act independently. Standard IQ tests administered after the surgery revealed Dr. P.’s intelligence still to be, for the most part, in the superior range; yet he could not handle many simple day-to-day activities and was unable to appreciate the nature of his deficits. His dysfunction was so severe that not only was returning to work as a surgeon out of the question, but also his brother had to be appointed his legal guardian. Previously Dr. P. had skillfully juggled many competing demands and had flexibly adjusted to changing situations and demands. Now, however, he was unable to carry out all but the most basic routines and those only in a rigid, inflexible manner. Furthermore, he had lost the ability to initiate actions and the ability to plan. (Smith and Kosslyn 2007: 283, after Lezak 1983)

In a classic case of dysexecutive syndrome following frontal lobe damage, the patient may have intact sensory and object-recognitional and (automatic, not reasoning-mediated) categorization abilities and memory systems, furnishing him with almost all the low-grade, automatic, stimulus-driven (e.g. sensory) knowledge of the world, triggered by the world, which the epistemic involuntarists find so compelling – Clarke’s (1986) involuntary ‘formation of beliefs’, Strawson’s (2003) ‘receptivity’, his ‘natural causality of reason’, his ‘waiting for content to come to mind’. Such a person may sometimes score normally even on a task as demanding as an IQ test6 or other tasks given to him, here by the psychologist, otherwise by the environment (cf. ‘environmental dependency syndrome’). Such a person’s cognition is as unbiased as the frontal lobe insult is severe, it is determined by the world triggering his unregulated mandatory lower brain processes, his beliefs are forced (Clarke) by whatever crosses his path; he makes no intrusions into this process of automatic afferent determination, he does not ‘pervert’ (Kornblith) the environment’s determination of his mental life:

Self-directed visual imagery, audition, covert self-speech, and the other covert re-sensing abilities that form nonverbal working memory do not have sufficient power to control behavior in many EF disorders. That behaviour remains largely under the control of the salient aspects of the immediate context. (Barkley 2012: 201)

You might, at a first encounter, not realize anything was wrong with such a patient. Is the victim of such a syndrome nevertheless not terribly, and specifically epistemically devastated? The patient cannot direct his thought. That’s just what it means to have impaired EF. He cannot adequately plan, choose a cognitive strategy, regulate his cognition. He cannot initiate, shift, relate or inhibit his thought in a controlled fashion. He has, crucially, impaired metacognitive abilities. He has impaired planning abilities, problem-solving capacities, capacities for action selection, task selection, strategy selection; impaired capacities for abstraction, for temporal scheduling. He cannot stay ‘on task’. He cannot adjust strategy to deal with novel problem situations. It is absurd to suppose he is not specifically epistemically devastated, and he is so devastated because he lacks the abilities we have and take for granted – in general: the ability to self-regulate, to control our own thought. He may be as effective a processor of tasks that are given to him by the environment (cf. ‘environmental dependency syndrome’) as an unimpaired agent, but he is terribly impaired in his ability to seek after the truth – he is terribly impaired as an inquirer.

Work on the EFs (often brilliant work) had been conducted by clinical neurologists/neuropsychologists investigating frontal lobe function through lesion studies spread over more than a century, reaching perhaps its apogee in the work of Luria (e.g. 1973) and his holistic notion, somewhat after Hughlings-Jackson, of ‘interactive functional systems’. This then made contact with the cognitive psychological tradition as it began to transition to studying the highest cognitive functions, in particular through the landmark paper by Baddeley and Hitch (1974) introducing the notion of working memory (WM) – with their original model’s central executive, phonological loop and visuospatial scratchpad. (The developing concept of WM is of huge importance in this story and will be considered in the chapter to come.) These two traditions then merged into a genuine cognitive neuropsychology, one studying higher brain–mind function. An influential early example of this would be Shallice’s (1982) two-component theory – one surprisingly consistent with the ‘two-stage’ armchair-psychological views of a number of the epistemologists we have seen thus far. This involved a ‘supervisory attentional system’ and a ‘contention scheduling system’.7 The former directs effortful attention and guides action (including, especially, mental action) through decision processes. Highly automatized processes (of the kind fitting the epistemological involuntarists’ entire conception of cognitive psychology) fall instead within the purview of Shallice’s ‘contention scheduling system’ – these often being spared in certain classic neurological syndromes involving frontal lobe damage (dysexecutive syndrome, perseveration, environmental dependency syndrome, etc.). As we saw for Lezak’s Dr. P., IQ performance (and other task-dependent activities) may be left intact in such syndromes, but high-level cognition is devastated – the EFs are devastated: there is terrible disruption of the characteristically human, characteristically agential, regulative control of cognition. However one terminologizes it, it is the appraisal of an intact agent’s exercise of this kind of control that is central to deontological epistemic appraisal.

In place of Shallice’s singular ‘supervisory attentional’ system, Lezak (1983) postulated four fundamental EFs: volition, planning, purposive action and ‘effective performance’. However, at the process level, there is radical dispute as to the number of separable executive processes we possess: from one, through to very many indeed. To give a flavour of the disagreement here, Table 3.2 is taken from Jurado and Rosselli (2007). It could easily be much longer.

Table 3.2 Concepts and components of executive functions

Source: Jurado and Rosselli (2007). Copyright Springer.

Notice that this table, large as it is, lists quite high-level, descriptive and/or superordinate process-level groupings of EFs. Were it to include more in the way of plausible subordinate processes under these headings, it would be considerably larger. As to a more intensional ‘definition’ (or at least an explicative summary) of EF as such: Sergeant et al. (2002) offer thirty-three definitions of EF. Barkley (2012) gives eighteen (useful) explicative definitions. The cumulative effect of these is explicative, heuristic, but by no means definitional. Most note that EF is an umbrella term for a very broad family of control processes and that these processes (often/usually) operate on lower-level cognitive processes – a point of some later importance.

One thing to note from the start is that, in addition to all the other sources of confusion about EF, many of these headings cover EFs that may be applicable at radically different psychological levels – over radically different time-frames and levels of explanation/description, say. So, many of the traditional experimental and clinical measures of EF are quite narrowly operationalized over the shortest of timescales with specifically cold-cognitive experimental variables: WM as a score on a letter-memory or n-back task; inhibition as a score on a go/no-go task or a flanker task; flexibility as a specific measure of task or set shifting – a trail-making or a card-sort test.8 But these measures, useful as they are, are continuous with and interpenetrate (and are sometimes predictive of) much higher-level variables operating at or just below the agential level: measures of cognitive–personality variables, planning and self-management capacities operating over long and sometimes very long timescales, values-laden (‘hot’, socioaffective) cognition, characteristically human cognition that involves considerable sociocultural scaffolding (e.g. education). I note merely that this is so, and perhaps, for a concept as sweeping and high level and reflexive and specifically human as EF, this variability in purview and focus is inevitable. In any event, this variegation in the concept is there: it is not my purpose to define it out of existence, and the reader must be aware of it. Barkley (2012: 176), coming from a clinical as well as experimental standpoint, importantly emphasizes the socioaffective and culturally mediated aspects of EF, seeing EF as ‘essentially self-determination’, involving as this does ‘the use of self-directed actions so as to choose goals and to select, enact, and sustain actions across time towards these goals usually in the context of others, often relying on social and cultural means’. At something closer to the process level, he sees the transition from the pre-executive to the executive level as involving six factors. At this narrower, more process level, EF is identified with self-regulation:

Six self-directed actions were identified as used by humans for self-regulation. They are the components of EF: Self-directed attention to create self-awareness, self-directed inhibition to create self-restraint, self-directed sensory-motor actions to create mental representations and simulations (ideation), self-directed speech to create verbal thinking, self-directed emotion and motivation to create conscious appraisal, and self-directed play (non-verbal and verbal reconstitution) to create problem solving, fluency or innovation. (Barkley 2012: 174)

The reader will note, then, that there is a great deal more agreement as to what EF is at the level of broad explicative, descriptive and clinical outline than there is as to exactly which are the (fundamental) executive processes subserving these. Purely for purposes of exegetical convenience, we will in the next chapter employ a currently common ordering of EFs under three superordinate factors (WM, inhibition and flexibility). Before getting to this tripartite ordering, and to end this chapter: here, without any attempt at order or logical priority or the avoidance of category error, are some examples of widely held EFs. WM (which is a huge component of EF) we will reserve for later.

We can direct our attention outwardly, as in sensory attention, towards different things in the world; but also inwardly, towards various of our own cognitive operations (the difference between these is probably not of fundamental psychological or epistemological importance). In either case, we choose to attend to this task or event or process or to this other one. In the case of executive attention, we select which cognitive operations we attend to, initiate and maintain. We direct our attention. (There is, in contrast, non-executive or ‘involuntary’ attention, which is under the control of the stimulus and mediated by very different neural pathways.) Executive attention may be directed attention per se or inhibitory attention (these are different). Directed: you may attend to the ink colour or semantically process the word. Inhibited: you may actively suppress your processing of the word, the better to attend to the ink colour. In general: you may look in the mirror or out of the windscreen; you may foveate at the cyclist without attention or attend to him.

2. Goal setting

Executive attention already involves goal setting (you choose what you attend to), but most would separate out as a separate EF the ability to choose which task you wish to achieve. Do you want to pull away from the kerb? Do you want to book a doctor’s appointment? Do you want to discover a list of executive processes? What task do you set for yourself?

3. Sequencing (‘task scheduling’)

Having set a goal (pull away from the kerb), we schedule how to implement it (mirror, signal, manoeuvre). Which sub-tasks are involved, and in which order must these be sequenced? (These are separate, experimentally dissociable functions.) Which other superordinate goals need to be sequenced in a cognitively costly attention-sharing process of further task scheduling?

4. Monitoring

You may check to see how well you are performing the task both as you perform it and very shortly afterwards. This may be a behavioural or a cognitive task, and these checks may involve motor or inner-cognitive activities. You may in principle check most, and perhaps any executive process for errors – and many lower cognitive processes besides. This illustrates the reflexive nature of these processes (you may apply the EFs to themselves – you may, for this example, monitor other EFs). Reflexivity is a point that will be much emphasized in the next chapter.

5. Inhibiting

We considered one simple example of this under inhibitory executive attention. There are others, and as they ascend in generality, they segue into a great family of systems/processes/variables, some very high order, some less so. At the lower level, Barkley (2012) distinguishes: (1) the capacity to suppress/disrupt/prevent a prepotent or dominant response; (2) the capacity to interrupt an ongoing response; and (3) the capacity to protect from interference those self-directed actions that are initiated and thus maintain the goal-directed actions that they are guiding. At a rather different level of generality, we have Gray’s behavioural inhibition system, Mischel’s gratification delay, various distinct literatures’ conceptions of self-regulation, and ‘impulse control’ – these are discussed in the next chapter. Inhibition is one of the leading candidates for a singular, unitary account of EF – at the very least, it is a hugely important family of processes.

6. Switching

You need to switch goals, sub-goals and tasks (task or set switching/shifting). You need to allocate finite attentional and WM resources first to this operation and then to that. This is not just sequencing (cf. the above); elegant experimental work establishes that there are specific switching costs (Monsell 2003). It is hard to switch tasks (there are cognitive/attentional costs to all these EFs: many of these costs are experienced phenomenologically, and all are operationalizable with performance indicators).

7. Planning

This is even more an umbrella term than others of these labels; a clinically useful and intuitive term for a great cluster of abilities most characteristically knocked out by frontal lobe damage. Of course, planning involves several of the putative processes above, and it operates over many different levels, specifically of time and space. You wish to get to work, get a PhD, arrange a drink for tonight, locate a philosophical literature in a research library. Your whole cognitive life involves planning – planning over many different time-scales and spatial distances. Planning is close to the heart of what executive control involves.

8. Maintenance of mental/attentional set (e.g. in the face of distraction)

You have made your plans, you have set your goals (and your sub-goals), but you must stay ‘on task’ through the operation of these cognitive schedules. You must continue to attend to the task in hand and not be distracted or ‘lured’ to other tasks. Frontal lobe damage profoundly impairs this ability (though sometimes, as with ‘perseveration’, it is the ability to discontinue or switch a task that is impaired).

9. Metacognition

All of the above are metacognitive abilities or components/features of metacognitive abilities, yet ‘metacognition’ is often separated out as a distinct EF. We possess extraordinary metacognitive capacities, many of them culturally (and sometimes technologically) mediated. The first of these to be studied was metamemory (our knowledge of/beliefs about our mnemonic abilities). Then there are all the rest – all your study skills, all your reflexive psychological awareness and control, your (prosthetically, not immediately applied9) gratification delay and time-discounting capabilities, all of your self-regulative capabilities and theory of mind. It is common to divide metacognition into metapsychological knowledge and metapsychological regulation (more of which in the next chapter). You know you have a poor memory for names and faces. You are introduced to your new colleagues and your values impress upon you the need to remember them. You know that unmediated effortful cognition will be useless here, and that mediation through low-level rehearsal strategies will be useless. Instead, you write their names with a description in your diary immediately after they leave the room, with brief biographical information. You survive potentially embarrassing situations thereafter until their names, faces and biographical data are securely in long-term memory.

10. Values-based cognition (‘hot’ cognition)

This is not separate from, but interpenetrates most or all of these EFs. You seek to reason as you ought. Continuous with the more purely cognitive inhibitory processes above, you also possess effortful control of socioaffective behaviour – both in itself and in interaction with the cognitive. This kind of cognition is mediated by different but neighbouring brain areas to the cold cognition with which it very closely integrates. There is a vast and famous literature from Phineas Gage onwards concerning frontal injury impairments in socioaffective cognition – in the capacity for responsible conduct. An impaired agent like Gage or Dr. P. is not responsible for his actions or cognition, as he has lost the capacity to control these, but an unimpaired agent is. You have, for example, a drive to intellectual honesty, a sense of responsibility, diligence. These capacities segue into variables more characteristically studied by individual differences psychologists than cognitive neuropsychologists; and personality variables, though not well understood at a neuropsychological level, are also assumed to be disproportionately mediated by the frontal lobes.

11. Cognitive–personality variables

Somewhat between the points made under ‘Inhibiting’ and ‘Values-based cognition’ above: agents differ in Big 5 conscientiousness, Big 5 openness to experience, need for cognition, impulse control, effortful control, response inhibition, self-regulation, gratification delay, motivation, internality of locus of control and consideration of future consequences: character, intellectual and otherwise.

12. Mediated cognitive control

As Aristotle notes, in a classic ‘tracing case’, we may mediate cognitive control through habits engendered by the exercise of said control (Aristotle 2000: III, v, 1114a). But we also simply exercise said control; this is what EF is, after all – the most highly controlled cognition we have. There are, though, other ways of more obliquely mediating cognitive control, and we consider some in the chapter to come. One may mediate cognitive control through other EF control (cf. the reflexivity motif repeated passim above) and through other ‘internal’ techniques (e.g. ‘cognitive cueing’ – control over our direction of thought), but also through motor–actional control and in other, functional, prosthetic ways.

The next chapter considerably expands upon these initial, explicative headings, demonstrating that even our current, inchoate understanding of EF constitutes a sophisticated body of theory and evidence, one vindicating the claim that we possess extraordinary powers of rational, self-regulative, value-laden, agential control of thought. Positively, these are powers more than sufficient to underwrite an epistemic deontology; negatively, they are more than sufficient to overturn ‘involuntarist’ arguments against any such deontology.