Preface

Growth is an omnipresent protean reality of our lives: a marker of evolution, of an increase in size and capabilities of our bodies as we reach adulthood, of gains in our collective capacities to exploit the Earth’s resources and to organize our societies in order to secure a higher quality of life. Growth has been both an unspoken and an explicit aim of individual and collective striving throughout the evolution of our species and its still short recorded history. Its progress governs the lives of microorganisms as well as of galaxies. Growth determines the extent of oceanic crust and utility of all artifacts designed to improve our lives as well as the degree of damage any abnormally developing cells can do inside our bodies. And growth shapes the capabilities of our extraordinarily large brains as well as the fortunes of our economies. Because of its ubiquity, growth can be studied on levels ranging from subcellular and cellular (to reveal its metabolic and regulatory requirements and processes) to tracing long-term trajectories of complex systems, be they geotectonic upheavals, national or global populations, cities, economies or empires.

Terraforming growth—geotectonic forces that create the oceanic and continental crust, volcanoes, and mountain ranges, and that shape watersheds, plains, and coasts—proceeds very slowly. Its prime mover, the formation of new oceanic crust at mid-ocean ridges, advances mostly at rates of less than 55 mm/year, while exceptionally fast new sea-floor creation can reach about 20 cm/year (Schwartz et al. 2005). As for the annual increments of continental crust, Reymer and Schubert (1984) calculated the addition rate of 1.65 km3 and with the total subduction rate (as the old crust is recycled into the mantle) of 0.59 km3 that yields a net growth rate of 1.06 km3.

That is a minuscule annual increment when considering that the continents cover nearly 150 Gm2 and that the continental crust is mostly 35–40 km thick, but such growth has continued during the entire Phanerozoic eon, that is for the past 542 million years. And one more, this time vertical, example of inevitably slow tectonic speeds: the uplift of the Himalayas, the planet’s most imposing mountain range, amounts to about 10 mm/year (Burchfiel and Wang 2008; figure 0.1). Tectonic growth fundamentally constrains the Earth’s climate (as it affects global atmospheric circulation and the distribution of pressure cells) and ecosystemic productivity (as it affects temperature and precipitation) and hence also human habitation and economic activity. But there is nothing we can do about its timing, location, and pace, nor can we harness it directly for our benefit and hence it will not get more attention in this book.

Slow but persistent geotectonic growth. The Himalayas were created by the collision of Indian and Eurasian plates that began more than 50 million year ago and whose continuation now makes the mountain chain grow by as much as 1 cm/year. Photo from the International Space Station (looking south from above the Tibetan Plateau) taken in January 2004. Image available at https://

Organismic growth, the quintessential expression of life, encompasses all processes by which elements and compounds are transformed over time into new living mass (biomass). Human evolution has been existentially dependent on this natural growth, first just for foraged and hunted food, later for fuel and raw materials, and eventually for cultivated food and feed plants and for large-scale exploitation of forest phytomass as well as for the capture of marine species. This growing human interference in the biosphere has brought a large-scale transformation of many ecosystems, above all the conversion of forests and wetlands to croplands and extensive use of grassland for grazing animals (Smil 2013a).

Growth is also a sign of progress and an embodiment of hope in human affairs. Growth of technical capabilities has harnessed new energy sources, raised the level and reliability of food supply, and created new materials and new industries. Economic growth has brought tangible material gains with the accumulation of private possessions that enrich our brief lives, and it creates intangible values of accomplishment and satisfaction. But growth also brings anxieties, concerns, and fears. People—be it children marking their increasing height on a door frame, countless chief economists preparing dubious forecasts of output and trade performance, or radiologists looking at magnetic resonance images—worry about it in myriads of different ways.

Growth is commonly seen as too slow or as too excessive; it raises concerns about the limits of adaptation, and fears about personal consequences and major social dislocations. In response, people strive to manage the growth they can control by altering its pace (to accelerate it, moderate it, or end it) and dream about, and strive, to extend these controls to additional realms. These attempts often fail even as they succeed (and seemingly permanent mastery may turn out to be only a temporary success) but they never end: we can see them pursued at both extreme ends of the size spectrum as scientist try to create new forms of life by expanding the genetic code and including synthetic DNA in new organisms (Malyshev et al. 2014)—as well as proposing to control the Earth’s climate through geoengineering interventions (Keith 2013).

Organismic growth is a product of long evolutionary process and modern science has come to understand its preconditions, pathways, and outcomes and to identify its trajectories that conform, more or less closely, to specific functions, overwhelmingly to S-shaped (sigmoid) curves. Finding common traits and making useful generalizations regarding natural growth is challenging but quantifying it is relatively straightforward. So is measuring the growth of many man-made artifacts (tools, machines, productive systems) by tracing their increase in capacity, performance, efficiency, or complexity. In all of these cases, we deal with basic physical units (length, mass, time, electric current, temperature, amount of substance, luminous intensity) and their numerous derivatives, ranging from volume and speed to energy and power.

Measuring the growth phenomena involving human judgment, expectations, and peaceful or violent interactions with others is much more challenging. Some complex aggregate processes are impossible to measure without first arbitrarily delimiting the scope of an inquiry and without resorting to more or less questionable concepts: measuring the growth of economies by relying on such variables as gross domestic product or national income are perfect examples of these difficulties and indeterminacies. But even when many attributes of what might be called social growth are readily measurable (examples range from the average living space per family and possession of household appliances to destructive power of stockpiled missiles and the total area controlled by an imperial power), their true trajectories are still open to diverse interpretations as these quantifications hide significant qualitative differences.

Accumulation of material possessions is a particularly fascinating aspect of growth as it stems from a combination of a laudable quest to improve quality of life, an understandable but less rational response to position oneself in a broader social milieu, and a rather atavistic impulse to possess, even to hoard. There are those few who remain indifferent to growth and need, India’s loinclothed or entirely naked sadhus and monks belonging to sects that espouse austere simplicity. At the other extreme, we have compulsive collectors (however refined their tastes may be) and mentally sick hoarders who turn their abodes into garbage dumps. But in between, in any population with rising standards of living, we have less dramatic quotidian addictions as most people want to see more growth, be in material terms or in intangibles that go under those elusive labels of satisfaction with life or personal happiness achieved through amassing fortunes or having extraordinarily unique experiences.

The speeds and scales of these pursuits make it clear how modern is this pervasive experience and how justified is this growing concern about growth. A doubling of average sizes has become a common experience during a single lifetime: the mean area of US houses has grown 2.5-fold since 1950 (USBC 1975; USCB 2013), the volume of the United Kingdom’s wine glasses has doubled since 1970 (Zupan et al. 2017), typical mass of European cars had more than doubled since the post–World War II models (Citroen 2 CV, Fiat Topolino) weighing less than 600 kg to about 1,200kg by 2002 (Smil 2014b). Many artifacts and achievements have seen far larger increases during the same time: the modal area of television screens grew about 15-fold, from the post–World War II standard of 30 cm diagonal to the average US size of about 120 cm by 2015, with an increasing share of sales taken by TVs with diagonals in excess of 150 cm. And even that impressive increase has been dwarfed by the rise of the largest individual fortunes: in 2017 the world had 2,043 billionaires (Forbes 2017). Relative differences produced by some of these phenomena are not unprecedented, but the combination of absolute disparities arising from modern growth and its frequency and speed is new.

Rate of Growth

Of course, individuals and societies have been always surrounded by countless manifestations of natural growth, and the quests for material enrichment and territorial aggrandizement were the forces driving societies on levels ranging from tribal to imperial, from raiding neighboring villages in the Amazon to subjugating large parts of Eurasia under a central rule. But during antiquity, the medieval period, and a large part of the early modern era (usually delimited as the three centuries between 1500 and 1800), most people everywhere survived as subsistence peasants whose harvest produced a limited and fluctuating surplus sufficient to support only a relatively small number of better-off inhabitants (families of skilled craftsmen and merchants) of (mostly small) cities and secular and religious ruling elites.

Annual crop harvests in those simpler, premodern and early modern societies presented few, if any, signs of notable growth. Similarly, nearly all fundamental variables of premodern life—be they population totals, town sizes, longevities and literacy, animal herds, household possessions, and capacities of commonly used machines—grew at such slow rates that their progress was evident only in very long-term perspectives. And often they were either completely stagnant or fluctuated erratically around dismal means, experiencing long spells of frequent regressions. For many of these phenomena we have the evidence of preserved artifacts and surviving descriptions, and some developments we can reconstruct from fragmentary records spanning centuries.

For example, in ancient Egypt it took more than 2,500 years (from the age of the great pyramids to the post-Roman era) to double the number of people that could be fed from 1 hectare of agricultural land (Butzer 1976). Stagnant yields were the obvious reason, and this reality persisted until the end of the Middle Ages: starting in the 14th century, it took more than 400 years for average English wheat yields to double, with hardly any gains during the first 200 years of that period (Stanhill 1976; Clark 1991). Similarly, many technical gains unfolded very slowly. Waterwheels were the most powerful inanimate prime movers of preindustrial civilizations but it took about 17 centuries (from the second century of the common era to the late 18th century) to raise their typical power tenfold, from 2 kW to 20 kW (Smil 2017a). Stagnating harvests or, at best, a feeble growth of crop yields and slowly improving manufacturing and transportation capabilities restricted the growth of cities: starting in 1300, it took more than three centuries for the population of Paris to double to 400,000—but during the late 19th century the city doubled in just 30 years (1856–1886) to 2.3 million (Atlas Historique de Paris 2016).

And many realities remained the same for millennia: the maximum distance covered daily by horse-riding messengers (the fastest way of long-distance communication on land before the introduction of railways) was optimized already in ancient Persia by Cyrus when he linked Susa and Sardis after 550 BCE, and it remained largely unchanged for the next 2,400 years (Minetti 2003). The average speed of relays (13–16 km/h) and a single animal ridden no more than 18–25 km/day remained near constant. Many other entries belong to this stagnant category, from the possession of household items by poor families to literacy rates prevailing among rural populations. Again, both of these variables began to change substantially only during the latter part of the early modern era.

Once so many technical and social changes—growth of railway networks, expansion of steamship travel, rising production of steel, invention and deployment of internal combustion engines and electricity, rapid urbanization, improved sanitation, rising life expectancy—began to take place at unprecedented rates during the 19th century, their rise created enormous expectations of further continued growth (Smil 2005). And these hopes were not disappointed as (despite setbacks brought by the two world wars, other conflicts, and periodic economic downturns) capabilities of individual machines, complicated industrial processes, and entire economies continued to grow during the 20th century. This growth was translated into better physical outcomes (increased body heights, higher life expectancies), greater material security and comfort (be it measured by disposable incomes or ownership of labor-easing devices), and unprecedented degrees of communication and mobility (Smil 2006b).

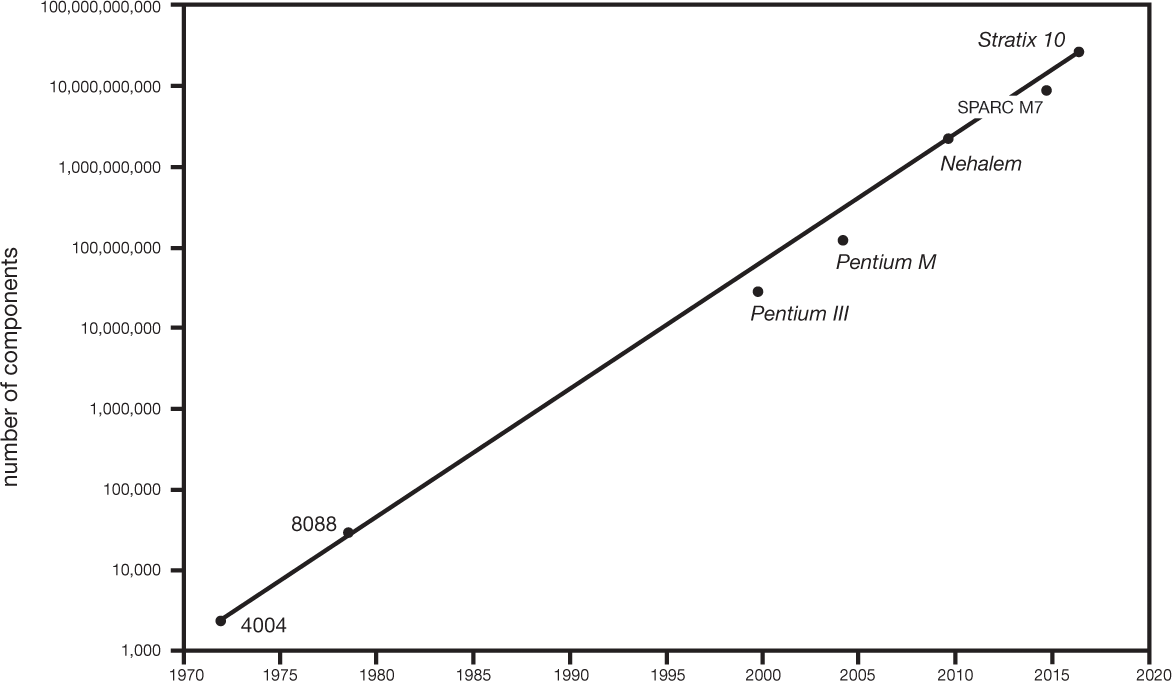

Nothing has embodied this reality and hope during recent decades as prominently as the growth in the number of transistors and other components that we have been able to emplace on a silicon wafer. Widely known as conforming to Moore’s law, this growth has seen the number of components roughly double every two years: as a result, the most powerful microchips made in 2018 had more than 23 billion components, seven orders of magnitude (about 10.2 million times to be more exact) greater than the first such device (Intel’s 4004, a 4-bit processing unit with 2,300 components for a Japanese calculator) designed in 1971 (Moore 1965, 1975; Intel 2018; Graphcore 2018). As in all cases of exponential growth (see chapter 1), when these gains are plotted on a linear graph they produce a steeply ascending curve, while a plot on a semilogarithmic graph transforms them into a straight line (figure 0.2).

A quintessential marker of modern growth: Moore’s law, 1971–2018. Semi-logarithmic graph shows steady exponential increase from 103 to 1010 components per microchip (Smil 2017a; IBM 2018b).

This progress has led to almost unbounded expectations of still greater advances to come, and the recent rapid diffusion of assorted electronic devices (and applications they use) has particularly mesmerized those uncritical commentators who see omnipresent signs of accelerated growth. To give just one memorable recent example, a report prepared by Oxford Martin School and published by Citi claims the following time spans were needed to reach 50 million users: telephone 75 years, radio 38 years, TV 13 years, Internet four years, and Angry Birds 35 days (Frey and Osborne 2015). These claims are attributed to Citi Digital Strategy Team—but the team failed to do its homework and ignored common sense.

Are these numbers referring to global or American diffusions? The report does not say, but the total of 50 million clearly refers to the United States where that number of telephones was reached in 1953 (1878 + 75 years): but the number of telephones does not equal the total number of their users, which, given the average size of families and the ubiquity of phones in places of work, had to be considerably higher. TV broadcasting did not have just one but a number of beginnings: American transmission, and sales of first sets, began in 1928, but 13 years later, in 1941, TV ownership was still minimal, and the total number of TV sets (again: devices, not users) reached 50 million only in 1963. The same error is repeated with the Internet, to which millions of users had access for many years at universities, schools, and workplaces before they got a home connection; besides, what was the Internet’s “first” year?

All that is just sloppy data gathering, and an uninformed rush to make an impression, but more important is an indefensible categorical error made by comparing a complex system based on a new and extensive infrastructure with an entertaining software. Telephony of the late 19th century was a pioneering system of direct personal communication whose realization required the first large-scale electrification of society (from fuel extraction to thermal generation to transmission, with large parts of rural America having no good connections even during the 1920s), installation of extensive wired infrastructure, and sales of (initially separate) receivers and speakers.

In contrast, Angry Birds or any other inane app can spread in a viral fashion because we have spent more than a century putting in place the successive components of a physical system that has made such a diffusion possible: its growth began during the 1880s with electricity generation and transmission and it has culminated with the post-2000 wave of designing and manufacturing billions of mobile phones and installing dense networks of cell towers. Concurrently the increasing reliability of its operation makes rapid diffusion feats unremarkable. Any number of analogies can be offered to illustrate that comparative fallacy. For example, instead of telephones think of the diffusion of microwave ovens and instead of an app think of mass-produced microwavable popcorn: obviously, diffusion rates of the most popular brand of the latter will be faster than were the adoption rates of the former. In fact, in the US it took about three decades for countertop microwave ovens, introduced in 1967, to reach 90% of all households.

The growth of information has proved equally mesmerizing. There is nothing new about its ascent. The invention of movable type (in 1450) began an exponential rise in book publishing, from about 200,000 volumes during the 16th century to about 1 million volumes during the 18th century, while recent global annual rate (led by China, the US, and the United Kingdom) has surpassed 2 million titles (UNESCO 2018). Add to this pictorial information whose growth was affordably enabled first by lithography, then by rotogravure, and now is dominated by electronic displays on mobile devices. Sound recordings began with Edison’s fragile phonograph in 1878 (Smil 2018a; figure 0.3) and their enormous selection is now effortlessly accessible to billions of mobile phone users. And information flow in all these categories is surpassed by imagery incessantly gathered by entire fleets of spy, meteorological, and Earth observation satellites. Not surprisingly, aggregate growth of information has resembled the hyperbolic expansion trajectory of pre-1960 global population growth.

Thomas A. Edison with his phonograph photographed by Mathew Brady in April 1878. Photograph from Brady-Handy Collection of the Library of Congress.

Recently it has been possible to claim that 90% or more of all the extant information in the world has been generated over the preceding two years. Seagate (2017) put total information created worldwide at 0.1 zettabytes (ZB, 1021) in 2005, at 2 ZB in 2010, 16.1 ZB in 2016, and it expected that the annual increment will reach 163 ZB by 2025. A year later it raised its estimate of the global datasphere to 175 ZB by 2025—and expected that the total will keep on accelerating (Reinsel et al. 2018). But as soon as one considers the major components of this new data flood, those accelerating claims are hardly impressive. Highly centralized new data inflows include the incessant movement of electronic cash and investments among major banks and investment houses, as well as sweeping monitoring of telephone and internet communications by government agencies.

At the same time, billions of mobile phone users participating in social media voluntarily surrender their privacy so data miners can, without asking anybody a single question, follow their messages and their web-clicking, analyzing the individual personal preferences and foibles they reveal, comparing them to those of their peers, and packaging them to be bought by advertisers in order to sell more unneeded junk—and to keep economic growth intact. And, of course, streams of data are produced incessantly simply by people carrying GPS-enabled mobile phones. Add to this the flood of inane images, including myriads of selfies and cat videos (even stills consume bytes rapidly: smartphone photos take up commonly 2–3 MB, that is 2–3 times more than the typescript of this book)—and the unprecedented growth of “information” appears more pitiable than admirable.

And this is one of the most consequential undesirable consequences of this information flood: time spent per adult user per day with digital media doubled between 2008 and 2015 to 5.5 hours (eMarketer 2017), creating new life forms of screen zombies. But the rapid diffusion of electronics and software are trivial matters compared to the expected ultimate achievements of accelerated growth—and nobody has expressed them more expansively than Ray Kurzweil, since 2012 the director of engineering at Google and long before that the inventor of such electronic devices as the charged-couple flat-bed scanner, the first commercial text-to-speech synthesizer, and the first omnifont optical character recognition.

In 2001 he formulated his law of accelerating returns (Kurzweil 2001, 1):

An analysis of the history of technology shows that technological change is exponential, contrary to the common-sense “intuitive linear” view. So we won’t experience 100 years of progress in the 21st century—it will be more like 20,000 years of progress (at today’s rate). The “returns,” such as chip speed and cost-effectiveness, also increase exponentially. There’s even exponential growth in the rate of exponential growth. Within a few decades, machine intelligence will surpass human intelligence, leading to The Singularity—technological change so rapid and profound it represents a rupture in the fabric of human history. The implications include the merger of biological and nonbiological intelligence, immortal software-based humans, and ultra-high levels of intelligence that expand outward in the universe at the speed of light.

In 2005 Kurzweil published The Singularity Is Near—it is to come in 2045, to be exact—and ever since he has been promoting these views on his website, Kurzweil Accelerating Intelligence (Kurzweil 2005, 2017). There is no doubt, no hesitation, no humility in Kurzweil’s categorical grand pronouncements because according to him the state of the biosphere, whose functioning is a product of billions of years of evolution, has no role in our futures, which are to be completely molded by the surpassing mastery of machine intelligence. But as different as our civilization may be when compared to any of its predecessors, it works within the same constraint: it is nothing but a subset of the biosphere, that relatively very thin and both highly resilient and highly fragile envelope within which carbon-based living organisms can survive (Vernadsky 1929; Smil 2002). Inevitably, their growth, and for higher organisms also their cognitive and behavioral advances, are fundamentally limited by the biosphere’s physical conditions and (wide as it may seem by comparing its extremes) by the restricted range of metabolic possibilities.

Studies of Growth

Even when limited to our planet, the scope of growth studies—from ephemeral cells to a civilization supposedly racing toward the singularity—is too vast to allow a truly comprehensive single-volume treatment. Not surprisingly, the published syntheses and overviews of growth processes and of their outcomes have been restricted to major disciplines or topics. The great classic of growth literature, D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form (whose original edition came out it in 1917 and whose revised and much expanded form appeared in 1942) is concerned almost solely with cells and tissues and with many parts (skeletons, shell, horns, teeth, tusks) of animal bodies (Thompson 1917, 1942). The only time when Thompson wrote about nonbiogenic materials or man-made structures (metals, girders, bridges) was when he reviewed the forms and mechanical properties of such strong biogenic tissues as shells and bones.

The Chemical Basis of Growth and Senescence by T. B. Robertson, published in 1923, delimits its scope in the book’s title (Robertson 1923). In 1945, another comprehensive review of organismic growth appeared, Samuel Brody’s Bioenergetics and Growth, whose content was specifically focused on the efficiency complex in domestic animals (Brody 1945). In 1994, Robert Banks published a detailed inquiry into Growth and Diffusion Phenomena, and although this excellent volume provides numerous examples of specific applications of individual growth trajectories and distribution patterns in natural and social sciences and in engineering, its principal concern is captured in its subtitle as it deals primarily (and in an exemplarily systematic fashion) with mathematical frameworks and applications (Banks 1994).

The subtitle of an edited homage to Thompson (with the eponymous title, On Growth and Form) announced the limits of its inquiry: Spatio-temporal Pattern Formation in Biology (Chaplain et al. 1999). As diverse as its chapters are (including pattern formations on butterfly wings, in cancer, and in skin and hair, as well as growth models of capillary networks and wound healing), the book was, once again, about growth of living forms. And in 2017 Geoffrey West summed up decades of his inquiries into universal laws of scaling—not only of organisms but also cities, economies, and companies—in a book titled Scale that listed all of these subjects in its long subtitle and whose goal was to discern common patterns and even to offer the vision of a grand unified theory of sustainability (West 2017).

Components of organic growth, be they functional or taxonomic, have received much attention, and comprehensive treatments deal with cellular growth (Studzinski 2000; Morgan 2007; Verbelen and Vissenberg 2007; Golitsin and Krylov 2010), growth of plants (Morrison and Morecroft 2006; Vaganov et al. 2006; Burkhart and Tomé 2012; Gregory and Nortcliff 2013), and animals (Batt 1980; Campion et al. 1989; Gerrard and Grant 2007; Parks 2011). As expected, there is an enormous body of knowledge on human growth in general (Ulijaszek et al. 1998; Bogin 1999; Hoppa and Fitzgerald 1999; Roche and Sun 2003; Hauspie et al. 2004; Tanner 2010; Floud et al. 2011; Fogel 2012).

Healthy growth and nutrition in children have received particular attention, with perspectives ranging from anthropometry to nutrition science, and from pediatrics and physiology to public health (Martorell and Haschke 2001; Hochberg 2011; Hassan 2017). Malthus (1798) and Verhulst (1845, 1847) published pioneering inquiries into the nature of population growth, whose modern evaluations range from Pearl and Reed (1920) and Carr-Saunders (1936) to Meadows et al. (1972), Keyfitz and Flieger (1991), Hardin (1992), Cohen (1995), Stanton (2003), Lutz et al. (2004), and numerous reviews and projections published by the United Nations.

Modern economics has been preoccupied with the rates of output, profit, investment, and consumption growth. Consequently, there is no shortage of inquiries pairing economic growth and income (Kuznets 1955; Zhang 2006; Piketty 2014), growth and technical innovation (Ruttan 2000; Mokyr 2002, 2009, 2017; van Geenhuizen et al. 2009), growth and international trade (Rodriguez and Rodrik 2000; Busse and Königer 2012; European Commission 2014), and growth and health (Bloom and Canning 2008; Barro 2013). Many recent studies have focused on links between growth and corruption (Mo 2001; Méndez and Sepúlveda 2006; Bai et al. 2014) and growth and governance (Kurtz and Schrank 2007; OECD 2016).

Publications are also dispensing advice on how to make all economic growth sustainable (WCED 1987; Schmandt and Ward 2000; Daly and Farley 2010; Enders and Remig 2014) and equitable (Mehrotra and Delamonica 2007; Lavoie and Stockhammer 2013). As already noted, the long life of Moore’s law has focused interest on the growth of computational capabilities but, inexplicably, there are no comprehensive book-length studies on the growth of modern technical and engineering systems, such as long-term analyses of capacity and performance growth in extractive activities and energy conversions. And even when including papers, there is only a limited number of publications dealing explicitly with the growth of states, empires, and civilizations (Taagepera 1978, 1979; Turchin 2009; Marchetti and Ausubel 2012).

What Is (and Is Not) in This Book

The impossibility of a truly comprehensive account of growth in nature and society should not be an excuse for the paucity of broader inquiries into the modalities of growth. My intent is to address this omission by examining growth in its many natural, social, and technical forms. In order to cover such a wide sweep, a single volume must be restricted in both its scope and depth of coverage. The focus is on life on Earth and on the accomplishments of human societies. This assignment will take us from bacterial invasions and viral infections through forest and animal metabolism to the growth of energy conversions and megacities to the essentials of the global economy—while excluding both the largest and the smallest scales.

There will be nothing about the growth (the inflationary expansion) of the universe, galaxies, supernovas, or stars. I have already acknowledged inherently slow growth rates of terraforming processes that are primarily governed by the creation of new oceanic crust with spreading rates ranging between less than two and no more than about 20 cm/year. And while some short-lived and spatially limited catastrophic events (volcanic eruptions, massive landslides, tsunami waves, enormous floods) can result in rapid and substantial mass and energy transfers in short periods of time, ongoing geomorphic activities (erosion and its counterpart, sedimentary deposition) are as slow or considerably slower than the geotectonic processes: erosion in the Himalayas can advance by as much as 1 cm/year, but the denudation of the British Isles proceeds at just 2–10 cm in every 1,000 years (Smil 2008). There will be no further examination of these terraforming growth rates in this book.

And as the book’s major focus is on the growth of organisms, artifacts, and complex systems, there will be also nothing about growth on subcellular level. The enormous intensification of life science research has produced major advances in our understanding of cellular growth in general and cancerous growth in particular. The multidisciplinary nature, the growing extent, and accelerating pace of these advances means that new findings are now reported overwhelmingly in electronic publications and that writing summary or review books in these fields are exercises in near-instant obsolescence. Still, among the recent books, those by Macieira-Coelho (2005), Gewirtz et al. (2007), Kimura (2008), and Kraikivski (2013) offer surveys of normal and abnormal cellular growth and death.

Consequently, there will be no systematic treatment of fundamental genetics, epigenetics and biochemistry of growth, and I will deal with cellular growth only when describing the growth trajectories of unicellular organisms and the lives of microbial assemblies whose presence constitutes significant, or even dominant, shares of biomass in some ecosystems. Similarly, the focus with plants, animals, and humans will not be on biochemical specificities and complexities of growth at subcellular, cellular, and organ level—there are fascinating studies of brain (Brazier 1975; Kretschmann 1986; Schneider 2014; Lagercrantz 2016) or heart (Rosenthal and Harvey 2010; Bruneau 2012) development—but on entire organisms, including the environmental settings and outcomes of growth, and I will also note some key environmental factors (ranging from micronutrients to infections) that often limit or derail organismic growth.

Human physical growth will be covered in some detail with focus both on individual (and sex-specific) growth trajectories of height and weight (as well as on the undesirable rise of obesity) and on the collective growth of populations. I will present long-term historical perspectives of population growth, evaluate current growth patterns, and examine possible future global, and some national, trajectories. But there will be nothing on psychosocial growth (developmental stages, personality, aspirations, self-actualization) or on the growth of consciousness: psychological and sociological literature covers that abundantly.

Before proceeding with systematic coverage of growth in nature and society, I will provide a brief introduction into the measures and varieties of growth trajectories. These trajectories include erratic advances with no easily discernible patterns (often seen in stock market valuations); simple linear gains (an hourglass adds the same amount of falling sand to the bottom pile every second); growth that is, temporarily, exponential (commonly exhibited by such diverse phenomena as organisms in their infancy, the most intensive phases in the adoption of technical innovation, and the creation of stock market bubbles); and gains that conform to assorted confined (restrained) growth curves (as do body sizes of all organisms) whose shape can be captured by mathematical functions.

Most growth processes—be they of organisms, artifacts, or complex systems—follow closely one of these S-shaped (sigmoid) growth curves conforming to the logistic (Verhulst) function (Verhulst 1838, 1845, 1847), to its precursor (Gompertz 1825), or to one of their derivatives, most commonly those formulated by von Bertalanffy (1938, 1957), Richards (1959), Blumberg (1968), and Turner et al. (1976). But natural variability as well as unexpected interferences often lead to substantial deviations from a predicted course. That is why the students of growth are best advised to start with an actual more or less completed progression and see which available growth function comes closest to replicating it.

Proceeding the other way—taking a few early points of an unfolding growth trajectory and using them to construct an orderly growth curve conforming to a specifically selected growth function—has a high probability of success only when one tries to predict the growth that is very likely to follow a known pattern that has been repeatedly demonstrated, for example, by many species of coniferous trees or freshwater fish. But selecting a random S-curve as the predictor of growth for an organism that does not belong to one of those well-studied groups is a questionable enterprise because a specific function may not be a very sensitive predictive tool for phenomena seen only in their earliest stage of growth.

The Book’s Structure and Goals

The text follows a natural, evolutionary, sequence, from nature to society, from simple, directly observable growth attributes (numbers of multiplying cells, diameter of trees, mass of animal bodies, progression of human statures) to more complex measures marking the development and advances of societies and economies (population dynamics, destructive powers, creation of wealth). But the sequence cannot be exclusively linear as there are ubiquitous linkages, interdependencies, and feedbacks and these realities necessitate some returns and detours, some repetitions to emphasize connections seen from other (energetic, demographic, economic) perspectives.

My systematic inquiry into growth will start with organisms whose mature sizes range from microbes (tiny as individual cells, massive in their biospheric presence) to lofty coniferous trees and enormous whales. I will take closer looks at the growth of some disease-causing microbes, at the cultivation of staple crops, and at human growth from infancy to adulthood. Then will come inquiries into the growth of energy conversions and man-made objects that enable food production and all other economic activities. I will also look how this growth changed numerous performances, efficiencies, and reliabilities because these developments have been essential for creating our civilization.

Finally, I will focus on the growth of complex systems. I will start with the growth of human populations and proceed to the growth of cities, the most obvious concentrated expressions of human material and social advancement, and economies. I will end these systematic examinations by noting the challenges of appraising growth trajectories of empires and civilizations, ending with our global variety characterized by its peculiar amalgam of planetary and parochial concerns, affluent and impoverished lives, and confident and uncertain perspectives. The book will close with reviewing what comes after growth. When dealing with organisms, the outcomes range from the death of individuals to the perpetuation of species across evolutionary time spans. When dealing with societies and economies, the outcomes range from decline (gradual to rapid) and demise to sometimes remarkable renewal. The trajectory of the modern civilization, coping with contradictory imperatives of material growth and biospheric limits, remains uncertain.

My aim is to illuminate varieties of growth in evolutionary and historical perspectives and hence to appreciate both the accomplishments and the limits of growth in modern civilization. This requires quantitative treatment throughout because real understanding can be gained only by charting actual growth trajectories, appreciating common and exceptional growth rates, and setting accomplished gains and performance improvements (often so large that they have spanned several orders of magnitude!) into proper (historical and comparative) contexts. Biologists have studied the growth of numerous organisms and I review scores of such results for species ranging from bacteria to birds and from algae to staple crops. Similarly, details of human growth from infancy to maturity are readily available.

In contrast to the studies of organismic growth, quantifications of long-term growth trajectories of human artifacts (ranging from simple tools to complex machines) and complex systems (ranging from cities to civilizations) are much less systematic and much less common. Merely to review published growth patterns would not suffice to provide revealing treatments of these growth categories. That is why, in order to uncover the best-fitting patterns of many kinds of anthropogenic growth, I have assembled the longest possible records from the best available sources and subjected them to quantitative analyses. Every one of more than 100 original growth graphs was prepared in this way, and their range makes up, I believe, a unique collection. Given the commonalities of growth patterns, this is an unavoidably repetitive process but systematic presentations of specific results are indispensable in order to provide a clear understanding of realities (commonalities and exceptions), limits, and future possibilities.

Systematic presentation of growth trajectories is a necessary precondition but not the final goal when examining growth. That is why I also explain the circumstances and limits of the charted growth, provide evolutionary or historical settings of analyzed phenomena, or offer critical comments on recent progression and on their prospects. I also caution about any simplistic embrace of even the best statistical fits for long-term forecasting, and the goal of this book is not to provide an extended platform for time-specific growth projections. Nevertheless, the presented analyses contain a variety of conclusions that make for realistic appraisals of what lies ahead.

In that sense, parts of the book are helpfully predictive. If a century of corn yields shows only linear growth, there is not much of a chance for exponentially rising harvests in the coming decades. If the growth efficiency of broilers has been surpassing, for generations, the performance of all other terrestrial meat animals, then it is hard to argue that pork should be the best choice to provide more protein for billions of new consumers. If unit capacities, production (extraction or generation) rates, and diffusion of every energy conversion display logistic progress, then we have very solid ground to conclude that the coming transition from fossil fuels to renewables will not be an exceptionally speedy affair. If the world’s population is getting inexorably urbanized, its energetic (food, fuels, electricity) and material needs will be shaped by these restrictive realities dictating the need for incessant and reliable, mass-scale flows that are impossible to satisfy from local or nearby sources.

Simply put, this book deals in realities as it sets the growth of everything into long-term evolutionary and historical perspectives and does so in rigorous quantitative terms. Documented, historically embedded facts come first—cautious conclusions afterward. This is, of course, in contradistinction to many recent ahistoric forecasts and claims that ignore long-term trajectories of growth (that is, the requisite energetic and material needs of unprecedented scaling processes) and invoke the fashionable mantra of disruptive innovation that will change the world at accelerating speed. Such examples abound, ranging from all of the world’s entire car fleet (of more than 1 billion vehicles) becoming electric by 2025 to terraforming Mars starting in the year 2022, from designer plants and animals (synthetic biology rules) making the strictures of organismic evolution irrelevant to anticipations of artificial intelligence’s imminent takeover of our civilization.

This book makes no radical claims of that kind; in fact it avoids making any but strongly justified generalizations. This is a deliberate decision resting on my respect for complex and unruly realities (and irregularities) and on the well-attested fact that grand predictions turn out to be, repeatedly, wrong. Infamous examples concerning growth range from those of unchecked expansion of the global population and unprecedented famines that were to happen during the closing decades of the 20th century to a swift takeover of the global energy supply by inexpensive nuclear power and to a fundamentally mistaken belief that the growth rate underlying Moore’s law (doubling every two years) can be readily realized through innovation in other fields of human endeavor.

The book is intended to work on several planes. The key intent is to provide a fairly comprehensive analytical survey of growth trajectories in nature and in society: in the biosphere, where growth is the result of not just evolution but, increasingly, of human intervention; and in the man-made world, where growth has been a key factor in the history of populations and economies and in the advancement of technical capabilities. Given this scope, the book could be also read selectively as a combination of specific parts, by focusing on living organisms (be they plants, animals, humans, or populations) or on human designs (be they tools, energy converters, or transportation machinery). And, undoubtedly, some readers will be more interested in the settings of growth processes—in preconditions, factors, and the evolutionary and historical circumstances of natural, population, economic, and imperial growth—rather than in specific growth trajectories.

Yet another option is to focus on the opposite scales of growth. The book contains plenty of information about the growth of individual organisms, tools, machines, or infrastructures—as well as about the growth of the most extensive and the most complex systems, culminating in musings about the growth of civilizations. The book is also a summation of unifying lessons learned about the growth of organisms, artifacts, and complex systems, and it can be also read as an appraisal of evolutionary outcomes in nature and as a history of technical and social advances, that is as an assessment of civilizational progress (record might be a better, neutral, designation than progress)

As always in my writings, I stay away from any rigid prescriptions—but I hope that the book’s careful reading conveys the key conclusion: before it is too late, we should embark in earnest on the most fundamental existential (and also truly revolutionary) task facing modern civilization, that of making any future growth compatible with the long-term preservation of the only biosphere we have.